Abstract

Background: During the second half of the 20th century, the literature on the doctor-patient relationship mainly dealt with the management of “difficult” (personality-disordered) patients. Similar problems, however, surround other types of “special” patients.

Method: An overview and analysis of the literature were conducted. As a result, such patients can be subcategorized by their main presentations; each requires a specific management strategy.

Results: Three types of “special” patients stir up irrational feelings in their caregivers. Sick celebrities threaten to focus public scrutiny on the private world of medical caregivers. VIPs generate awe in caregivers, with loss of the objectivity essential to the practice of scientific medicine. Potentates unearth narcissism in the caregiver-patient relationship, which triggers a struggle between power and shame. Pride, privacy, and the staff's need to be in control are all threatened by introduction of the special patient into medicine's closed culture.

Conclusion: The privacy that is owed to sick celebrities should be extended to protect overexposed staff. The awe and loss of medical objectivity that VIPs generate are counteracted by team leadership dedicated to avoiding any deviation from standard clinical procedure. Moreover, the collective ill will surrounding potentates can be neutralized by reassuring them that they are “special”—and by caregivers mending their own vulnerable self-esteem.

When individuals with an uncommon social standing attain the status of patients, their medical care can be compromised.1–9 Since the mid–20th century, dozens of articles and reviews on this phenomenon have appeared, variously discussing the special patienthood of world leaders,2,3,10–22 doctors as medical patients,4,5,23–47 doctors as psychiatric patients,48–60 famous authors,2,8,61 the wealthy,3,62,63 and miscellaneous other artists and notables.2,3,5–7

Typically, the literature on the relationship between “special” patients and the caregiving system (formerly termed the doctor-patient relationship) has used the terms celebrity and VIP interchangeably. This article attempts to tease apart conflated categories64 of “special” patients, to add precision to the terminology,65,66 and to familiarize caregivers with management strategies for typical problems.

As our experience with such patients has increased, it has been useful for us to distinguish between staff reactions to media exposure (the celebrity phenomenon) and staff reactions of awe toward the patient (the VIP syndrome). To this lexicon is added potentate to denote the “want-to-be” celebrity and the “pseudo-VIP.” The situations caused by these 3 categories of “special” patients differ from one another, and each requires a specific type of management. Psychological reactions of caregivers to celebrities, to VIPs, and to potentates illustrate systems phenomena related to what psychiatry has termed narcissism and countertransference.67–75

CELEBRITY PATIENTS

Celebrities make news; their lives interest the public most when something bad happens to them. Unfortunately, when they get sick, there is no switch to turn the spotlight off. Even when a celebrity's medical condition is kept secret (except from caregivers), the celebrity patient's newsworthiness inflicts on caregivers a cluster of problems so predictable that it is almost syndromic.

Since caregivers are used to protecting the privacy of patients, maintaining confidentiality is not usually the main problem faced when taking care of a celebrity. The difficulty lies in the caregivers' protection of their own privacy when they suddenly find themselves in the glare of the spotlight. The ruthless pressure of media exposure76 can highlight worries the caregiver has about clinical competence. Clinicians know that they are not perfect; they pray that minor errors in diagnosis and treatment will go unnoticed. In celebrity care, however, the public eye or “jury” overlooking the caregiver's shoulder questions the caregiver's decisions.1

A component of the problem encountered when treating a celebrity is the caregiver's training. While onstage, professional actors learn to “ignore” the audience. In contrast, caregivers are not trained to do in public what they usually do in private. Caring for a patient “in public” creates an enormous distraction, one that may detract from clinical competence.

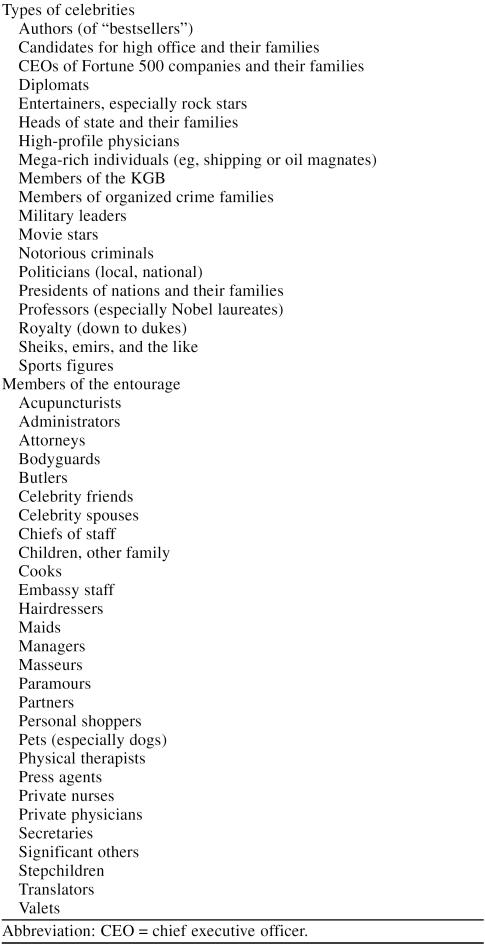

A related problem faced when caring for a celebrity is highlighted in Table 1. Celebrities tend to carry with them a retinue. The result is that the care of celebrities is always scrutinized, frequently questioned, and sometimes bitterly criticized. Lay people often wonder why experts malfunction in routine medical situations. The explanation lies in the cumulative pressure of having to do one's job and do it well—hard enough in the absence of public scrutiny—with the whole world watching.2,3

Vignette. During a nationally televised trial of an accused serial killer, the prisoner developed left flank pain, hematuria, and a blood pressure of 230/119. Under heavy guard and in the glare of the national media, he was brought to the emergency ward. His attorney, a florid man who affected a white ten-gallon hat, set up a press conference literally on the hospital's doorstep. His posture before the cameras implied somehow that the hospital was on trial.

Dysfunction in hospital procedure developed within hours. Some patients and visitors, although able to watch the elaborate security on television, experienced anxiety about their own safety. The medical staff displayed an unusual exaggeration of the normal friction among coworkers in high-stress environments. People were more irritable and dogmatic than usual. The team of physicians with ultimate responsibility failed to designate 1 individual to respond to the media and instead put forth a panel of 3 service chiefs. Their press conferences were notable for interservice competition, jargon-filled descriptions of the patient's care, and defensive replies to press questions that called for only a simple medical explanation.

Table 1.

“Special” Patients and Members of the Entourage

This allegorical vignette involves an accused or convicted individual whose celebrity revolved around a crime (previously termed negative celebrity1). Here, the notorious individual, in custody, was brought to the medical setting. Oddly enough, the situation was similar to that of any other celebrity. There was publicity, a “coterie” (in this instance, law enforcement officers and the media), and conflicting demands on caregivers that revolved around the patient's role as a public figure. Realizing in such situations that the negative celebrity is “just another celebrity” can prepare the staff to protect the patient's rights and use the standard algorithm for celebrity care.

Time, Place, and Privacy

The timing of medical encounters with celebrities is of 2 varieties: emergencies and planned events. In only 1 way are emergencies easier: the coterie is usually kept away from the medical arena. (This is not always the case, however: no fewer than 4 Secret Service agents were in the operating room during President Reagan's emergency thoracic surgery14; unnecessary at best, since none was scrubbed in.)

Elective encounters with the celebrity entail much less time pressure. Two preexisting, relatively autonomous power structures—the celebrity coterie and the medical system—come together around a single task, and the basic script is, “Let's do lunch.” The 2 heads of the power structures (hospital and celebrity) designate various individuals to confer with one another at lower levels. Large medical centers usually have an individual versed in celebrity care, and this person will know what questions to ask, such as, “Will you bring your own chef?” Follow-up visits and readmissions tend to be patterned after the first, with subsequent encounters providing the opportunity to correct systems errors that occurred previously.

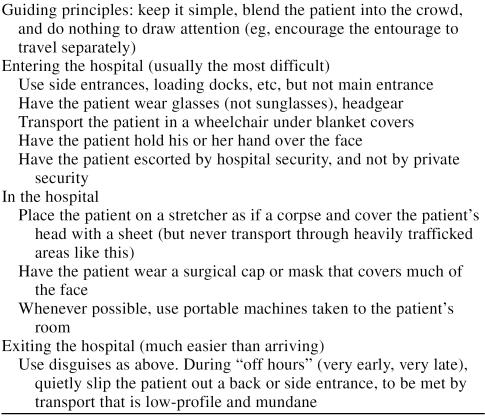

The single most important nonclinical issue in the care of the celebrity is information management. Information should flow exactly the same as it does for a “normal” patient, but under a closely guarded pseudonym or alias. Table 2 summarizes strategies based on our practical experience for protection of the celebrity patient's privacy.

Table 2.

Strategies Used to Maintain Patient Privacy

Politics of Coterie Management

There are 2 domains in the celebrity's life, personal and public. From the outset, the person in charge on the caregiver side needs to have complete access to the key individuals responsible for these matters. The issue of access needs to be explicit, with guaranteed lines of communication with the patient's “power person” and next of kin.

The individual responsible for clinical care must insist that there be only 2 nonmedical individuals directly receiving clinical information about the celebrity: the next of kin, usually the spouse, and the patient's senior aide or administrator. Ideally, conferences to convey clinical information should be held with both of these individuals, in the presence of the patient, with everyone else (except perhaps security) excluded.

The caregiver in charge may need to appeal to the celebrity patient to ratify this structure. In a worst-case scenario (one with coterie infighting and a celebrity too ill to adjudicate), the chief clinician may have to resort to a counter-manipulation that depends on the coterie's own fear of the spotlight. For example, in the rare but uncomfortable event of the spouse and the aide trying to cut one another “out of the loop,” the physician may have to “play poker” and resort to a bit of a bluff: They have to cooperate or find a new treating physician. (The caregiver's power in this situation derives from the coterie's fear of publicly explaining why the doctor has resigned.)

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

Difficulties in celebrity care are multiplied when the illness involves neurologic or psychiatric impairment,2,3,17,18 largely because of the reaction of the coterie. When President Eisenhower had a myocardial infarction,12 there was unprecedented public disclosure of medical details, even down to his bowel movements. Later, however, when a cerebrovascular accident impaired Eisenhower's thinking, the cover-up reflexes of the coterie resembled those following President Wilson's stroke.17,18

Neuropsychiatric illness places a burden on the celebrity's clinician because, as Kucharski put it, “The care of political patients is inextricable from the care of the State.”3(p74) Cognitive or emotional impairment multiplies the usual conflict of interests, pitting the patient's right to privacy against the public's “right to know.”18,19 In one recent instance, a “comprehensive” history by a medical member of President Reagan's coterie21 made no mention of Alzheimer's disease despite the paper's bruiting its own candor and the public's right to know.

VIPs

Legend has it that Winston Churchill coined the acronym VIP to denote a high government official or high-ranking member of the military.2 In Churchill's usage, such an individual has considerable prestige or influence and commands special privilege in a particular arena. Connoting VIP as one who generates awe in a particular domain means that an individual can be very important in certain situations and not necessarily be of any interest to the media.

The paradigm of the VIP in the term's original sense is the medical caregiver who is treated in his or her own institution. Much of the literature in this field, especially the classic work, concerns the physician as patient. When physicians become patients, they can cause a distinctive uproar in the medical environment because of their emotional importance, a social phenomenon that goes beyond the mere fact of patienthood.

Vignette. Dr. June Finnegan was a legend in her own hospital. A member of the first class of women admitted to her medical school, she went on to become the mentor of a score of oncologists. She had authored a major textbook and chaired a national organization in her field. Never married and with no relations except a mentally retarded sister, she made the hospital her home. Although she had a huge clinical practice, she was never too busy for the people in her hospital “family” who got sick or who had a relative with cancer. A fixture, she could be seen at any hour walking the halls, stethoscope and purse in one hand, briefcase in the other.

When she received her own diagnosis of cancer, she put herself in the hands of a former trainee. As her disease progressed, the network of consultants and caregivers around her proliferated. Over time, the team showed increasing uncertainty and deferred to her to make clinical decisions in her own case. One day, after the third consultation, she weakly exploded: “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph! Here I am, surrounded by physicians—what I really need is a doctor!”

Ingelfinger's essay “Arrogance”27 describes a similar situation: Over time, Dr. Ingelfinger's isolation as a VIP came to be directly proportional to his biomedical expertise on the cancer that was killing him. His knowledge and status as a physician generated crippling awe in his caregivers. What was needed was a doctor who would take responsibility since, in the words of Moore, “The fundamental act of medical care is assumption of responsibility.”77(pvii)

Reactions to Physician-Patients

Investigation of medical caregivers' personal emotions toward “special” patients (as contrasted with reactions to publicity) started in the mid–20th century with a 3-page report4 in Cancer. The authors studied delay in seeking care, measured as the time from an individual experiencing the first symptom to the individual consulting a physician. The 229 cancer patients who happened to be physicians in the sample showed no less delay than the 2000 lay patients. More interesting than the delay of physician-patients in seeking care, however, was the delay of their doctors in pursuing the diagnosis and arranging treatment. The authors blamed the treating physicians' delays on the physician-patients and their failure to consider the possibility that doctors who treat doctors overidentify and collude with their (considerable) denial.24

Around the time the report in Cancer was published, the reasons for doctors' malfunctioning in the patient role were widely discussed, mainly by doctors themselves. A trickle of first-person narratives by doctors became a torrent,23–47 yet these many views of the doctor-as-patient converged on a single fact: physicians experience their own illnesses as narcissistic insults to which they react with shame38,41 and with culturally-induced denial, especially when the disease is psychiatric.48–60

While problems in the treatment of VIPs arise as a function of the importance of the VIP to caregivers, the VIPs potential for commanding special privileges can also upset the closed system of medicine. A VIP's ability to go outside the chain of command in an effort to heal narcissistic injury can sabotage the regimen. In the treatment of psychiatrically hospitalized physicians, dysfunctional patterns arose when staff prescribed one form of clinical care but were countermanded by administrators exerting pressure in a different direction.5

Physicians have a need to see themselves as invulnerable. Once ill, the physician is often unable to let another doctor assume control. Physician-patients often defend themselves with (conscious or unconscious) fantasies of immortality and healthy denial that often has a historical basis: According to Robinowitz, “A sizable number of medical students or their families have experienced serious or potentially life-threatening illness during childhood.”59(p138) Many sick doctors describe (intentionally and unintentionally) VIP phenomena—isolation, withdrawal, and starvation for information—in these illness narratives. A major problem cited in the literature is the assumption by the treating physician that a physician-patient needs less explanation about the illness, injury, treatment, and caregiving routine; actually, the converse is true.34

Too much and too little.

In the caregiver role are the doctors' doctors, frightened themselves of becoming ill. Consequently, they under-identify with the patient and use distancing as a defense against overidentification. Role theory sees doctor and patient roles as necessarily complementary, with the doctor role inverse to the patient role. The expectations of each party are complementary and distinct, whether explicit or implicit. When they fall ill, however, doctors who cannot accept the sick role throw confusing signals into the system; already anxious, the doctors' doctors cannot decode them.52

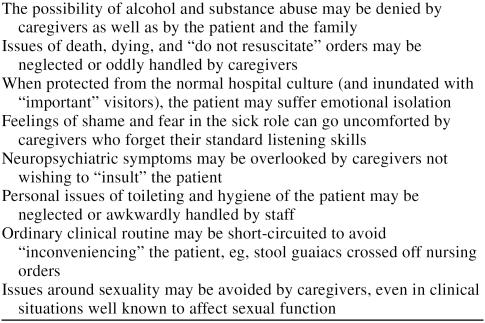

As a result of this “role strain,” caregivers may order too many or too few tests or prescribe treatments that are too conservative or too radical.24 Laboratory tests, consultations, and invasive studies are associated with opposing tendencies in the care of the VIP: The caregiver's anxiety about overlooking something may lead to a greater-than-ordinary utilization of resources. The desire to spare the caregiver-as-patient the pain of studies or exposure to peers and colleagues may lead to stinting on studies and consultations. Awe and its opposite, shame, seem equally disruptive of the optimal, balanced caregiver-patient relationship. Some typical consequences of deviations from standard care are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Deviations From Standard Operating Procedure in the Care of “Special” Patients

VIP Syndrome or Celebrity Phenomenon?

While it is not always possible to separate caregiver dysfunction in reaction to the spotlight (the celebrity phenomenon) from dysfunction because of personal awe (the VIP syndrome), events surrounding the Kennedy assassination provide a useful contrast.78–82

No spotlight could be brighter than the one on Dallas in 1963. Yet from the moment Kennedy was shot until the moment he was pronounced dead in Parkland Hospital, standard operating procedure was followed. Caregivers responded to Kennedy exactly like any other gunshot victim from all indications, including the prompt end to the resuscitation attempt. If one extrapolates from other instances of terminal care of presidents (Washington,18 Garfield21), it was a resuscitation that might have dragged on for hours, if not days.

The minute Kennedy was given the last rites, however, a series of deviations from standard procedure typical of those occasioned by awe (and its opposite) began. In the presence of Texas law enforcement officers and Justice of the Peace Theron Ward, Secret Service Agent Roy H. Kellerman forcibly removed Kennedy's body. Kellerman and agents pushing the stretcher swept aside the Dallas medical examiner, Dr. Earl Rose, who was attempting to block their exit. Hours later, with the chain of evidence badly broken, the autopsy was conducted out of proper jurisdiction. Worse, it was performed not by experts in forensics but by pathologists selected because of emotional and political considerations—an example of what has been termed “chief's syndrome.”20 Twenty-nine years later, with some understatement, Rose characterized the autopsy as “less than optimal.”81(p2807) “The law was broken,” Rose said, “and it is very disquieting to me to sacrifice the law as it exists for any individual, including the President. … People are governed by rules, and in a time of crisis it is even more important to uphold the rules.” A Dallas autopsy “would have been free of any perceptions of outside influences. … After all, if Oswald had lived, his trial would have been held in Texas and a Texas autopsy would have assured a tight chain of custody on all the evidence.”81(p2806) As had sometimes happened in his life,18 in death, Kennedy received too much awe and too little care.

POTENTATES

“Potentates” (and members of their coterie) see themselves as “big shots” and expect to be treated as such. But, unlike celebrities, they possess no particular magnetism for publicity. Unlike VIPs, their caregivers do not hold them in awe. The dysfunction they trigger in the staff is related neither to publicity nor to overidentification. Potentates in the medical setting generate crises over issues of power and privilege. They may have some of the external trappings of VIPs or celebrities, but to their caregivers they are no more than “difficult” patients who happen to be wealthy.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition,67 the official psychiatric diagnostic system in the United States, defines the core of narcissistic personality disorder by 2 leading traits, grandiosity and lack of empathy. Narcissistic personality disorder is diagnosed when an individual manifests at least 5 of the following traits: (1) arrogance; (2) a lust for power through beauty, love, brilliance, or money; (3) convictions of “specialness”; (4) a hunger for admiration; (5) a sense of entitlement; (6) an exploitative and manipulative nature; (7) stunted empathy and an inability to “feel into” other people; (8) enviousness; and (9) displays of contemptuousness. Although these are lifelong personality traits, they may be dramatically magnified by the stress of injury or illness.

It can be a bruising experience when such a patient treats a caregiver with contempt. In dealing with individuals with prominent narcissistic traits, the only thing the caregiver can count on is that at some point the narcissist will treat medical people as things, objects, tools, or slaves. Being prepared for this scenario makes one less likely to compromise clinical judgment and patient management.

Vignette. A 52-year-old princess from an oil-rich emirate was hospitalized for stabilization of her asthma. She and the prince ordinarily lived in Paris, France, where they spent their lives visiting doctors and being visited by their children.

The afternoon of her arrival marked the first explosion. What began as an admission interview ended with a nurse fleeing the room in a hail of invective. The patient's English was excellent, with a full command of vernacular insults, and her resentments were many. The room was too small. Her husband had only 1 room. Their staff was forced to share a third. The food was bad, the service was inept. The nurses were incompetent, as well as disrespectful, clumsy, and probably all thieves. (This last she would peculiarly emphasize by brandishing a thick packet of $100 bills and then clutching it to her chest.) The loudest explosion occurred with the arrival of the pulmonologist, a young woman. This proved it, the patient screamed, the hospital really despised her or it would not insult her by sending a woman doctor!

Over time, she calmed down, in large part because of a treatment plan insulating her from female caregivers. By the end of her stay, she took to showing gratitude by flicking a $100 bill in the direction of whatever caregiver was in the room.

“Difficult” patients68–75 like our mythical princess deviate from the typical patient role.83 To conform to the social role, a patient has to actually be sick, must want to get well, should be compliant with the regimen, has to relinquish the prerogatives of the healthy, and, not at all least, should display gratitude toward the caregiver. When patients are deviant from any of these elements of the sick role, caregivers become distressed or malfunction. Often they develop some of the above traits of narcissism as a reaction to the patient.

Potentates are individuals whose grandiosity and contempt for others are buttressed by actual power in the world. Sometimes this power derives from talent or industry; sometimes, just luck. Despite whatever appears on the surface, though, at the deepest level, such individuals are full of shame. They are terrified of being found out and exposed as impostors. Their effort to promote a grandiose image is typically to reassure themselves or to provide a distraction from intense anxiety. Because of their stunted or absent empathy, they make bad spouses, bad friends, bad parents, and bad patients.

As psychiatric patients, potentates have difficulty directly approaching the staff; they tend to communicate indirectly through their power intermediaries. They devalue care given to them as coming only from their external powers and do not credit it to their intrinsic worth. They have little ability to trust others' gratuitous acts of kindness or care because of their deep self-doubts that required compensation by means of external supplies. Potentates trigger the following chain of events: The patient obtains certain special privileges, and staff members withdraw from the patient emotionally; the patient demands more special privileges as if to compensate for the emotional isolation, and the staff withdraws even further. The usual “solution” for the vicious cycle is aborted treatment.5

Under the stress of any illness, those with narcissistic personalities may regress to a state where they resemble individuals with the more florid, acting-out borderline personality disorder. Borderline patients are notorious for their dramatic swings from love to hate and back again and for their inconsistent and exaggerated view of themselves and others. A leading characteristic is “splitting.” Splitting shows itself by the way the patient sees the world through a split-screen view: one half good, the other bad. Most problematic in the medical setting is when the patient splits the staff into 2 warring factions.84–86 The staff unwittingly acts out the patient's worldview.

Splitting occurs when one staff faction wants to indulge the patient and another faction insists on no special privileges. The special-patient literature mirrors this “splitting” and confuses 2 phenomena: (1) the need to comply absolutely with standard medical procedure and (2) the option to give in to the patient's sense of “specialness” in the nonclinical domain, for instance, the trappings of status. Some of the literature counsels against any indulgence. This point of view mandates treatment of the patient “just like any other patient,” as if the medical setting were a democracy. The contrary view holds that the setting must be prepared to show such a patient “special consideration: the patient's great need for status must be given the same respect as any other symptom.”5(p191) One proponent of this view wryly points out that the effort of ignoring such a difference in social status paradoxically enhances its impact.51

“CODE PURPLE” AND DISASTER PLANNING

Hospitals must have written protocols for catastrophes such as plane crashes, earthquakes, and terrorism that flood emergency services and overwhelm a hospital. Smith and Shesser20 reviewed the literature following the attempted assassination of President Reagan. On the basis of their experiences at George Washington University Hospital, they recommended the inclusion of additional procedures to deal with the arrival of a mega-VIP/celebrity, such as a Reagan or a Kennedy.

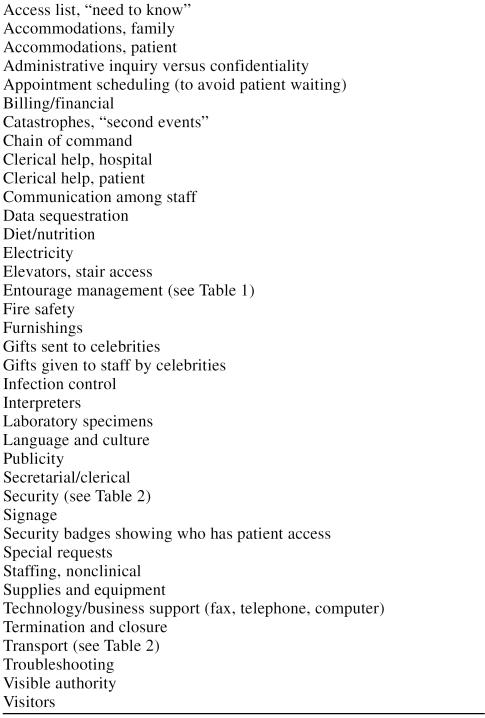

Table 4 offers a detailed checklist of relevant issues for the administrative and clinical leaders who will be ultimately responsible for such an event. The use of an exhaustive list to draft “Code Purple” procedures for managing these events can minimize oversights when policy is drafted and plans are made. Accidents bring out the best and worst in people, and crises enhance the unpredictability of the “human factor.” One excellent general rule for minimizing surprise from the human factor is, ironically, to keep tight control over “mechanical factors,” such as access policies spelled out in advance, routine versus emergency signage, traffic flows and alternate routes, policies on temporary and date-expiring security badges, and the like. While most of the items in Table 4 are self-explanatory, the following paragraphs provide elaboration on some of the terminology used.

Table 4.

Checklist of Nonmedical Concerns for Hospital Administrators

Accommodations

The largest request at our institution to date was for an entire floor; this was negotiated down to 4 rooms (1 each for patient, family, staff, and security). The overflow occupied a full floor at a hotel 6 blocks away. This arrangement, however, necessitated a fleet of 15 limousines to shuttle people from the hotel to the waiting area in the hospital, which at any one time contained 50 to 100 individuals, including FBI and Secret Service agents.

Catastrophes and “Second Events”

Disaster plans are almost always written to handle 1 emergency at a time, but history shows that crises may not wait in queue.87 No one likes to think of the idea, but an event that injures a mega-celebrity may simultaneously injure 100 or 200 other individuals. Some thought needs to be given to the “second event,” for instance, the occurrence of a “Code Purple” when another crisis is already overtaxing the hospital.

Gifts Sent to Celebrities

Gifts for a mega-celebrity can constitute a major problem for the hospital from the standpoint of volume alone. They also pose a security risk. After the assassination attempt on President Reagan, George Washington University Medical Center was flooded with flowers that had to be screened for bombs, with multiple singing telegrams, and, quite problematically, with balloons: “You didn't want a balloon to burst. The Secret Service agents were already jumpy.”16(p1)

Gifts Given to Staff by Celebrities

Some patients offer gifts to the staff. Much depends on whether the gift is for the institution or an individual. Some years ago, one patient was allowed to live in the hospital without charge until her death because of an agreement that the hospital would be the beneficiary of her estate. Among the gifts offered to individuals in our staff have been trips around the world, books, money, jewelry (including the “inevitable Rolex,” mentioned elsewhere1), and crystal.

In our hospital, all monetary gifts to the nursing staff go into a special gifts fund, the proceeds of which are used for the common benefit (e.g., plant improvements, staff education). Policies are still evolving, but current thinking seems to be in the direction that considers accepting individual gifts (or services, or even participating in barter) to be ethically questionable.88 One hinge of the issue is, Does the gift affect objectivity in the caregiver? The other is, Does the gift skew staff attention and service toward the giver at the expense of other patients?

Language and Culture

A file of what special requests go with which cultures is constantly being expanded and updated in our setting. Scheduling the fast for the weeks of Ramadan, where to store Orthodox icons, and scheduling laboratory tests to avoid the Sabbath are some of the entries that might go in such a file.

Special Requests

Large urban centers learn to expect the unexpected: We have had figs and tea biscuits flown in from London, England; acquired special mattresses; and planned a luncheon for 20. The general principle governing special requests is to be prepared to grant reasonable ones, but to ask ahead of time for some idea of what special-needs requests may come up.

While such a list aspires to exhaustiveness, each hospital will need to assess its own physical plant, customs, and culture to make sure that nothing is overlooked and “Code Purple” is anticipated in advance.

CONCLUSION

“Special” patients stir up dysfunctional feelings in their caregivers. Sick celebrities threaten to focus public attention on the private world of those caring for them. VIPs generate awe in caregivers and a loss of the objectivity that is said to be essential to the practice of scientific medicine. Potentates unearth the issue of narcissism in the caregiver-patient relationship, triggering a struggle between power and shame. Privacy, self-esteem, and the staff's need to be in control are all threatened by the introduction of “special” patients into the closed system of medical care.

Even if a celebrity's medical condition remains secret except to caregivers, the fact of the patient's newsworthiness causes a characteristic cluster of problems. VIPs, by comparison, may not interest the news media at all (the classic example being doctors and nurses treated in their own institutions). Yet, when VIPs become patients, they cause a distinctive uproar in the medical environment because of their felt importance. Potentates are not seen by medical caregivers as having importance beyond their patienthood, yet potentates think of themselves as special and act like it. Unlike celebrities, they possess no particular magnetism for publicity. Unlike VIPs, their caregivers do not hold them in awe. Crises generated in the medical setting by the potentate come from dissonant views between patient and staff over power and privilege.

The situations caused by these 3 categories of “special” patients differ from one another, and each instance requires a particular type of management. The privacy that sick celebrities need should be extended to protect overexposed staff. The awe and loss of medical objectivity that VIPs generate can be counteracted by team leadership specifically designed for and dedicated to avoiding any deviation from standard operating procedure. Finally, the collective ill will surrounding potentates is neutralized by reassuring them that they are “special”—and by caregivers mending their own vulnerable self-esteem.

An important history lesson can be learned from emergencies involving the “mega-VIP” or “super-celebrity,” such as a U.S. president: Any large urban hospital needs to have a written “Code Purple” plan attached to its disaster blueprint. Such an algorithm can minimize the impact of the crisis on patient care elsewhere in the hospital.

Footnotes

The authors report no financial affiliations or other relationships relevant to the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- Groves JE, Dunderdale BA. Practical approaches to the celebrity patient. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. 1998 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, Committee on Governmental Agencies. The VIP With Psychiatric Impairment. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1973 [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski A. On being sick and famous. Political Psychol. 1984;5:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins GF, MacDonald MC, Pack GT. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of physicians with cancer. Cancer. 1953;6:624–626. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195305)6:3<624::aid-cncr2820060320>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub W. “The VIP syndrome”: a clinical study in hospital psychiatry. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1964;138:181–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saari C, Johnson SR. Problems in the treatment of VIP clients. Soc Casework. 1975;576:599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Feuer EH, Karasu SR. A star-struck service: impact of the admission of a celebrity to an inpatient unit. J Clin Psychiatry. 1978;39:743–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange RE. The VIP with illness. Military Med. 1980;145:473–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block AJ. Beware of the VIP syndrome [editorial] Chest. 1993;104:989. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.4.989b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher MS. America's Last King: An Interpretation of the Madness of George III. New York, NY: Scribner's. 1941 [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L. The commitment and suicide of King Ludwig II of Bavaria. Am J Psychiatry. 1954;111:100–107. doi: 10.1176/ajp.111.2.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski A. Medical management of political patients: the case of Dwight D. Eisenhower. Persp Biol Med. 1978;22:115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breo DL. MDs, hospital ready for Reagan. Am Med News. 1981 1,2,17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom M. All the President's doctors. Med World News. 1981;22:9–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breo DL. Pope's physicians redeem a request. Am Med News. 1981;24:1,7,14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The trauma case in the emergency room was the president of the United States. Health Care Secur Safety Manage. 1981;2:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BE. The Impact of Illness on World Leaders. Philadelphia, Pa: University of Pennsylvania Press. 1986 [Google Scholar]

- MacMahon EB, Curry L. Medical Cover-Ups in the White House. Washington, DC: Farragut Publishing. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Crispell KR, Gomez CF. Hidden Illness in the White House. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- Smith MS, Shesser RF. The Emergency Care of the VIP Patient. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1421–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811243192119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beahrs OH. The medical history of President Ronald Reagan. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:86–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasby CG. Eisenhower's Heart Attack: How Ike Beat Heart Disease and Held on to the Presidency. Lawrence, Kan: University Press of Kansas. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Pinner M, Miller BF. When Doctors Are Patients. New York, NY: WW Norton. 1952 [Google Scholar]

- White RB, Lindt H. Psychological hazards of treating physical disorders of medical colleagues. Dis Nerv Syst. 1963;24:304–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen W. Surgeon Under the Knife. New York, NY: Dell. 1976 [Google Scholar]

- Sacks O. Awakenings. New York, NY: Random House. 1976 [Google Scholar]

- Ingelfinger FJ. Arrogance. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1507–1511. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012253032604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- I had a phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 1980;8174:922–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur L. An astrocytoma. Lancet. 1980;8380:786–787. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetten D Jr. Coping with blindness. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:458–460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108203050811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin D. Compounding the ordeal of ALS: isolation from my fellow physicians. N Engl J Med. 1982;308:506–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208193070827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The day I became old: the story of a physician. Lancet. 1982;8269:441–442. [Google Scholar]

- Creditor MC. Me and migraine. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1029–1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198210143071630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn KH. Chemotherapy from an insider's perspective. Lancet. 1982;8279:1006–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra FJ. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1982;8265:215–216. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todes C. Inside parkinsonism: a psychiatrist's personal experience. Lancet. 1983;8331:977–978. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullan F. Vital Signs. New York, NY: Dell. 1983 [Google Scholar]

- Stoudemire A, Rhoads JM. When the doctor needs a doctor: special considerations for the physician-patient. Ann Intern Med. 1983 98(5 pt 1). 654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks O. A Leg to Stand On. New York, NY: Summit Books. 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Mack RM. Lessons from living with cancer. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1640–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198412203112520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn RA. Between two worlds: physicians as patients. Med Anthropol Q. 1985;16:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mullan F. Seasons of survival: reflections of a physician with cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:270–273. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507253130421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzuk P. When the patient is a physician. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1409–1411. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711263172209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum ER. A Taste of My Own Medicine: When the Doctor Is the Patient. New York, NY: Random House. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- Selzer R. Raising the Dead. New York, NY: Whittle Books/Viking. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Kapur N. ed. Injured Brains of Medical Minds: Views From Within. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Poulson J. Bitter pills to swallow. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1844–1846. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806183382512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel JP. The social roles of doctor and patient in psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Psychiatry. 1954;17:369–376. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1954.11022982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MM, Strecker EA. Physicians as psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1966;116:915–919. doi: 10.1176/ajp.116.10.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent MO, Robinson EA, Latt L. Physicians as patients: private psychiatric hospital experience. Can Med Assoc J. 1969;100:403–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein B. The Manipulator. New Haven, Conn: Yale University. 1973 [Google Scholar]

- Glass GS. Incomplete role reversal: the dilemma of hospitalization for the professional peer. Psychiatry. 1975;38:132–144. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1975.11023843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro ET, Pinsker H, Shale JH III. The mentally ill physician as practitioner. JAMA. 1975;232:725–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RE. A study of 100 physician psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1977;134:1119–1123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.10.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RC, Carroll GJ, and Buxton WD. The Care and Management of the Sick and Incompetent Physician. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas. l978 [Google Scholar]

- Shortt SED. ed. Psychiatric Illness in Physicians. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas. 1982 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preven DW. Physician suicide: the psychiatrist's role. In: Schieber SC, Doyle BB, eds. The Impaired Physician. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing Corporation. 1983 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle BB. Responsibility, confidentiality, and the psychiatrically ill physician. In: Schieber SC, Doyle BB, eds. The Impaired Physician. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing Corporation. 1983 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Robinowitz CB. The physician as patient. In: Schieber SC, Doyle BB, eds. The Impaired Physician. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing Corporation. 1983 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison KR. An Unquiet Mind. New York, NY: Knopf. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Cousins N. Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company. 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl CW. Psychoanalysis of the rich, the famous, and the influential. In: Lindon JA, ed. The Psychoanalytic Forum, vol 5. New York, NY: International Universities Press. 1975 90–121. [Google Scholar]

- Stone MH. Treating the wealthy and their children. Int J Child Psychother. 1972;1:15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff G. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Brown RW. How shall a thing be called? Psychol Rev. 1958;65:14–21. doi: 10.1037/h0041727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RW. Words and Things. Glencoe, Ill: Free Press. 1958 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Groves JE. Difficult patients. In: Cassem NH, ed. The MGH Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. 4th ed. Chicago, Ill: Mosby-Yearbook, Inc. 1997 337–366. [Google Scholar]

- Groves JE. Personality disorders, 1: general approaches to difficult patients. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. 1998 591–597. [Google Scholar]

- Groves JE. Personality disorders, 2: approaches to specific behavioral presentations. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, eds. The MGH Guide to Psychiatry in Primary Care. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. 1998 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Ronningstam E, Gunderson J, Lyons M. Changes in pathological narcissism. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:253–257. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves JE. Management of the borderline patient on a medical or surgical ward: the psychiatric consultant's role. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1975;6:337–348. doi: 10.2190/5EQU-KW17-VGPL-9D67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:883–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197804202981605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves JE. Borderline personality disorder. N Engl J Med. 198l;305:259–262. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198107303050505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves JE, Beresin EV. Difficult patients, difficult families. New Horiz. 1998;6:331–343. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. Medicine and the media. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:87–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore FD. Metabolic Care of the Surgical Patient. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Company. 1959 [Google Scholar]

- Micozzi MS. Lincoln, Kennedy, and the autopsy [editorial] JAMA. 1992;267:2791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breo DL. JFK's death: the plain truth from the MDs who did the autopsy. JAMA. 1992;267:2794–2803. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.20.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The injuries to JFK [letter series] JAMA. 1992;268:1681–1685. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490130069018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breo DL. JFK's death, 2: Dallas MDs recall their memories. JAMA. 1992;267:2804–2807. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.20.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden MM. Unnatural Death: Confessions of a Medical Examiner. New York, NY: Ivy Books. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Parsons T. Illness and the role of the physician: a sociological perspective. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1951;21:452–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1951.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main TF. The ailment. Br J Med Psychol. 1957;30:129–145. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1957.tb01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton HA, Schwartz MS. The Mental Hospital. New York, NY: Basic Books. 1954 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenhan DL. On being sane in insane places. Science. 1973;179:250–258. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4070.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrow C. Normal Accidents: Living With High-Risk Technologies. New York, NY: Basic Books. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Gabbard GO, Nadelson C. Professional boundaries in the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1995;273:1445–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]