Abstract

Preventing weight regain after the loss of excess weight is challenging for people, especially for ethnic minorities in the U.S. A 6-month weight loss maintenance intervention designed for Pacific Islanders, called the PILI Lifestyle Program (PLP), was compared with a 6-month standard behavioral weight loss maintenance program (SBP) in a pilot randomized controlled trial using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach. Adult Pacific Islanders (n=144) were randomly assigned to either PLP (n=72) or SBP (n=72), after completing a 3-month weight loss program. Successful weight maintenance was defined as a participants’ post-intervention weight change remaining ≤3% of their pre-intervention mean weight. Both PLP and SBP participants achieved significant weight loss maintenance (p≤0.05). Among participants who completed at least half of the prescribed sessions, PLP participants were 5.1-fold (95% CI=1.06–24; p=0.02) more likely to have maintained their initial weight loss than SBP participants. The pilot PLP shows promise as a lifestyle intervention to address the obesity-disparities of Pacific Islanders and thus warrants further investigation.

Key words/phrases: weight loss maintenance, weight regain, Pacific Islanders, weight loss, ethnic minority health, obesity

The maintenance of weight loss, or preventing weight regain, is challenging for many people who lose excess weight. They often begin to regain weight within 6 to 12 months of making this effort (Perri & Corsica, 2002). Many regain one-third of their weight within the first year and return to baseline by the second year (Curioni & Lourenco, 2005; Turk et al., 2009). There are many health benefits to losing excess weight and keeping it off for people who are overweight and obese, such as improving blood pressure, physical functioning, and diabetes management, if not its prevention (Knowler et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2001; Norris et al., 2002).

Weight loss programs that focus on diet, exercise, and behavior modification can lead to a clinically meaningful weight loss of 5%–10% (Knowler et al., 2002; Wing, 2004). Many of these weight loss programs typically include a maintenance phase, between 6 to 12 months post-weight loss treatment, that involves monthly sessions that are follow-ups to the weight loss sessions (Perri & Corsica, 2002). Despite having maintenance sessions, many people still have difficulty maintaining their weight loss. Wing and colleagues suggest that weight loss maintenance sessions are not as efficacious as could be because they are mere extensions of the weight loss program (Wing, Tate, Gorin, Raynor, & Fava, 2006).

Researchers suggest that different strategies are needed to prevent weight regain from those used to achieve initial weight loss (Elfhag & Rossner, 2005; Perri & Corsica, 2002). Studies demonstrate the efficacy of interventions designed to prevent weight regain. Using a self-regulation approach, the Study to Prevent Regain (STOP Regain) found that an 18-month face-to-face program and internet-based program were superior to a newsletter control group in 314 people who had already lost 10% of body weight using various weight loss means (Wing et al., 2006). Within 6 months, the researchers found significant differences in weight loss maintenance in which the face-to-face participants were less likely to regain weight (−0.02kg±4.3) than internet-based (1.2kg±4.2) and control participants (1.5kg±3.6).

Wing and Jeffery (1999) examined the effects of recruiting participants alone or with friends/family members who were assigned to either standard behavior therapy or behavior therapy with social support training. At 6-month follow-up, they found participants who were recruited with family/friends and who also received social support training were better able to maintain their weight loss (66%) than those who were recruited alone and whose support person received the standard behavior therapy (24%). This demonstrates the benefits of recruiting participants with a support person into a weight loss maintenance program. It also demonstrates, along with the findings of the STOP Regain study, that the positive effects of an intervention focused on weight regain prevention, compared with a standard behavioral intervention, can be observed within 6 months following initial weight loss.

Although the studies reviewed here are promising, weight loss maintenance is challenging for many non-white ethnic populations. They tend to lose less weight and are more likely to regain their weight than whites given the same obesity intervention, most likely due to socio-economic/socio-cultural factors affecting obesity treatment (Kumanyika, 2002). Many ethnic minorities in the U.S. are more likely to be economically disadvantaged; to experience socio-ecological stressors; and to live in obesiogenic environments that increase their risk for obesity and related disorders (Kumanyika, 2002; Mau et al., 2008). Among the factors associated with weight loss maintenance, family and socio-environmental factors play a key role (Elfhag & Rossner, 2005; Tinker & Tucker, 1997), especially among economically-challenged ethnic minority populations (Davis, Clark, Carrese, Gary, & Cooper, 2005). The maintenance of weight loss is complicated by many psychosocial (e.g., acculturation challenges), family (e.g., larger families to support and maintain), and work (e.g., lower paying jobs) stressors and by the types of living environments (e.g., poor access to healthier food options). Thus, culturally-relevant interventions designed for weight loss maintenance in ethnically diverse populations are needed, especially those that focus on family and community supports.

To address this need for Pacific Islanders, such as Native Hawaiians, Samoans, Chuukese, and Filipinos, a community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership was formed called the Partnership to Improve Lifestyle Interventions (PILI) ‘Ohana Project (POP). CBPR is a research approach that actively/equitably involves community and academic partners in addressing health disparities (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). The POP is comprised of 5 community organizations serving Pacific Islanders in Hawai‘i and scientists from the University of Hawai‘i. The POP’s CBPR partnership is described in more detail in Nacapoy et al. (Nacapoy et al., 2008). The need for culturally-informed obesity interventions for Pacific Islanders in the U.S. is evident in their greater overweight/obesity (82%) and diabetes prevalence (22 %) compared with other ethnic populations and the larger U.S. population (Grandinetti et al., 2007; Mau, Sinclair, Saito, Baumhofer, & Kaholokula, 2009).

The POP’s partnership conducted a comprehensive obesity assessment of Pacific Islander communities in Hawai‘i, which included focus groups, informant interviews, and environmental evaluations. The methods and results of these assessments have been described by Nacapoy et al. (2008) and Mau et al. (2008; 2010). Overall, it was found that Pacific Islanders’ immediate social (family/friends) and physical (e.g., access to parks/gyms) environments were essential to their weight loss maintenance efforts by either encouraging or inhibiting their maintenance of positive behavior change. This information, with findings from the scientific literature, informed the design of a novel family and community focused weight loss maintenance program called the PILI Lifestyle Program (PLP). The behavioral strategies and foci of the PLP are consistent with empirically-supported behavior change theories that emphasize the modeling/reinforcing effects of a person’s social and physical environment on individual behavior (Baranowski et al., 2003). It also is consistent with Pacific Islanders’ cultural beliefs/values where both immediate and extended families (‘ohana) are important to daily functioning and decision making (Kaholokula et al., 2008).

Using a CBPR approach, the POP’s partnership conducted a pilot randomized controlled trail (RCT) to test the effectiveness of the PLP as a community-based and community-led weight loss maintenance intervention for Pacific Islanders. We report here the result of this RCT that examined the effects of the PLP in achieving weight loss maintenance compared with a standard behavioral weight loss maintenance program (SBP) over a 6-month period. Study participants completed a 3-month intervention designed to initiate weight loss, which was an adaptation of the Diabetes Prevention Project’s Lifestyle Intervention (DPP-LI) by the POP community-academic partnership to the Pacific Islander population (Mau et al., 2010).

Methods

Participants

Pacific Islander participants (n=144) were those who completed a 3-month DPP-LI adapted weight loss program and willing to enroll in a 6-month weight loss maintenance program between 2007 and 2008. Only 15% (n=25) of participants who completed the DPP-LI opted not to continue on into this weight maintenance intervention study. Participants who declined to participant in the weight maintenance study did not differ statistically in terms of mean weights and BMI values from those who were randomized into the study (p>0.05). Other pre-weight loss baseline characteristics and weight loss intervention outcomes for this cohort can be found in Mau et el. (2010). Participants entered the weight loss maintenance phase with a mean weight loss of 1.6kg (SD=3.7) and interquartile range of 4.5 kg.

The eligibility criterion for this study was completion of the 3-month DPP-LI to initiate weight loss. The criteria for participation in the 3-month DPP-LI was as follows: a) Pacific Islander (Native Hawaiian, Chuukese, Samoan, and Filipino); b) ≥18 years or older; c) overweight/obese defined as BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 or ≥ 23 kg/m2 (for Filipinos only; Inoue & Zimmet, 2000); d) willing/able to perform 150 minutes of brisk walking per week (or equivalent) and a dietary regimen to induce weight loss of 1–2 lbs/week; and e) identify at least 1 family member or friend to provide support throughout the program. Participants with a medical condition that might affect their ability to safely complete the intervention or their ability to exercise had obtained written permission from a physician before beginning weight loss effort.

Pacific Islanders in the U.S. includes people with origins in the original inhabitants of the Polynesian, Micronesian, or Melanesian islands (Mau et al., 2009). Table 2 shows the distribution of participants across the specific Pacific Islander groups represented in this sample: Native Hawaiians (n=75), Samoans (n=16) and Chuukese (n=38). For the purpose of our study, Filipinos (often classified as “Asian”) were included (n=9) in this study given their similar risk profile as Pacific Islanders for obesity-related diseases in Hawai‘i (Grandinetti et al., 2007). A small minority of participants included Pacific Islanders who did not report their specific ethnicity (n=2) and non-Pacific Islanders (n=4). All Native Hawaiian participants were native speakers of the English language. The English speaking fluency and comprehension of the other Pacific Islander participants varied but were at a level adequate for participation in the study based on observation by a community interviewer during the eligibility screening of each participant for entry into the 3-month DPP-LI adapted intervention.

Table 2.

| Characteristic | PLP (N=72) | SBP (N=72) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) or M ± SD | n (%) or M ± SD | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Chuukese | 14 (19) | 24 (33) |

| Filipino | 5 (7) | 4 (6) |

| Native Hawaiian | 39 (54) | 36 (50) |

| Samoan | 10 (14) | 6 (8) |

| Other Pacific Islander | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Non-Pacific Islander | 2 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Community Organization | ||

| Kula no Nā Po‘e Hawai‘i¶§ | 21 (29) | 9 (13) |

| Hawai‘i Maoli§ | 8 (11) | 12 (17) |

| Ke Ola Mamo | 17 (24) | 20 (28) |

| Kokuka Kalihi Valley | 12 (17) | 11 (15) |

| Kalihi-Pālama Health Cntr¶ | 14 (19) | 20 (28) |

| Age (years)٨ | 50 ± 14 | 49 ± 15 |

| Females† | 56 (78) | 66 (92) |

| Education level٨ | ||

| Less than H.S. | 16 (23) | 18 (25) |

| H.S. diploma/GED | 16 (23) | 16 (22) |

| Some college/tech. | 20 (28) | 21 (29) |

| College degree | 19 (27) | 17 (24) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never married | 16 (22) | 21 (29) |

| Currently married | 40 (56) | 32 (44) |

| Disrupted marital status | 16 (22) | 19 (26) |

| Weight (kg)* | 107 ± 32 | 99 ± 27 |

| BMI | 40 ± 9.6 | 39 ± 8.3 |

Note. PLP=PILI Lifestyle Program, SBP = Standard Behavioral Follow-up Program.

Baseline= time point immediately following randomization into weight loss maintenance intervention.

Fisher’s exact test, p=0.0353.

Fisher’s exact test, Kula vs. Kalihi-Pālama, p=0.0257.

Fisher’s exact test, Kula vs. Hawai‘i Maoli, p=0.0451.

At end of weight loss treatment program (prior to weight loss maintenance intervention).

Education level and age unknown for 1 participant.

The difference in baseline weights (µd=7.0, 95% CI=−2.7–17) did not differ statistically from zero (p=0.16).

Study Design

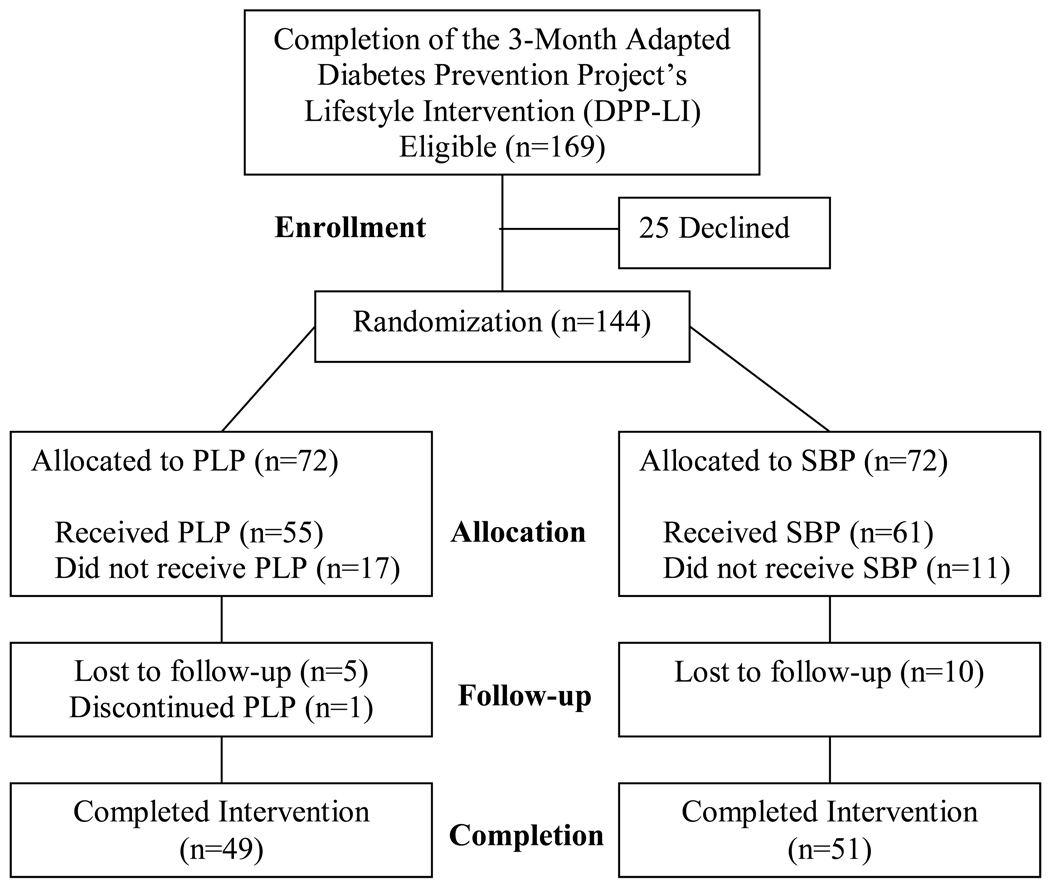

Guiding the design of our pilot RCT was a CBPR approach in which the POP’s community partners worked side-by-side with the academic partners in designing the PLP and in determining the study design as described in detail by Nacapoy et al. (2008) and by Mau et al. (2010). Briefly, we designed a pilot RCT to test the efficacy of the PLP delivered face-to-face compared with the SBP delivered over telephone as depicted in Figure 1. Because this was a pilot study to determine the feasibility and efficacy of a novel intervention (PLP), we purposefully limited the interventions’ length to 6 months. The findings of past studies suggest that differences between two interventions in weight regain can be captured within 6 months following initial weight loss (Wing & Jeffery, 1999; Wing et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram showing the flow of participants in the randomized trial

The participants were enrolled, given the interventions, and assessed across the five POP community organizations, all of which were completed within their respective community settings and by their own community recruiters, assessors, and peer educators. The 5 community organizations were Kokua Kalihi Valley Family Comprehensive Services (KKV), Kalihi-Pālama Health Center (KPHC; community health centers), Ke Ola Mamo Native Hawaiian Health Care System (KOM), Kula no Nā Po‘e Hawai‘i (KULA; a Hawaiian Homestead organization), and Hawai‘i Maoli (HM) of the Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs. For more details about these organizations see Nacapoy et al. (2008).

Participants were randomly assigned in blocks of 6 (Efird et al., 2007), stratified by community organization, to one of two weight loss maintenance programs: 1) PLP (n=72) or 2) SBP (n=72). Information on weight (kg) collected from participants at the beginning of the weight loss maintenance intervention (immediately following randomization; n=144) and 6 months afterwards for those who completed the interventions (n=100). A $10 store gift card was given to participants for attending each assessment occasion.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and the Native Hawaiian Health Care System. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. A data safety monitoring board (DSMB), which consisted of 1 cardiologist, 2 clinical health psychologists, and 1 nurse educator, was convened to ensure participants’ safety and to monitor possible adverse events due to the intervention.

Interventions

The PLP was comprised of 6 monthly sessions, lasting about 1½ hours in length each, delivered in groups (6–10 participants) by a trained community peer educator in the community setting. Table 1 summarizes the foci of each session and the order of their delivery. For Chuukese and Filipino participants at the KPHC site, the sessions were delivered in their native language by a bilingual community peer educator. For Chuukese and Samoan participants at the KKV site, the sessions were delivered both in English and concurrent translation into the Chuukese and Samoan language by a bilingual translator. Thus, each session at KKV took an average of 2 hours in length. To ensure the best approximation from English to these other languages, the bilingual translators were all health professional specially trained to translate health information and they based their translations on the English version of the intervention materials.

Table 1.

Summary of the Sessions Delivered to the Participants by Intervention Group

| Month | PILI Lifestyle Intervention (PLP) | Standard Behavioral Follow-up Program (SBP) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

Note: For the SBP participants, the individual review of their healthy eating and physical activity goals included identifying behavior change strategies that they found helpful and assisting in modification of their goals if needed.

Each PLP session was accompanied with education materials, handouts, action plans, and homework assignments. The community peer educators were trained on the delivery of each session and a PLP manual was used to ensure standardization of delivery and delivery fidelity. Participants were asked to identify and invite at least one family member or friend to attend each session with them but it was not mandatory for participation. The foci and strategies of the PLP were identified by community assessment and with input from the community investigators (Mau et al., 2010).

PLP was designed to build on the behavioral weight loss strategies, diet, exercise, and stress control strategies learned, and the individual action planning practiced, in the 3-month DPP-LI weight loss program (Mau et al., 2010). Family and community activities are also incorporated, designed to build and identify a supportive weight loss maintenance environment specific to each participant. The family activities were designed to encourage and illicit support from family/friends for the participants’ identified healthy lifestyle goals. Activities included family meal and physical activity planning, identifying types of support needed (e.g., instrumental, emotional) from family and friends, how to effectively communicate one’s healthy lifestyle goals, and how to deal with challenging family/social situations (e.g., social gatherings). Community support activities involved identifying naturally occurring resources (e.g., parks and healthy eating establishments) in their respective communities and sharing what they identified with other group members. The family and community exercises were to be completed between monthly sessions and designed to keep the participants active in their weight loss maintenance.

The SBP was comprised of 6 monthly phone call follow-up sessions, lasting 15–30 minutes in length each, delivered individually by a trained community peer educator. Table 1 summarizes the foci of each follow-up session. For Chuukese, Filipino, and Samoan participants at the KPHC and KKV, these phone call sessions were delivered to them in their native language by a trained bilingual community educator in the same manner described earlier. Each phone call was scripted to ensure standardization of delivery. SBP was designed to follow-up on the behavioral weight loss strategies, diet, exercise, and stress control strategies learned and the individual action planning practiced in the 3-month DPP-LI weight loss program. The follow-up calls included a review of weight loss strategies and the DPP-LI educational materials and focused on assisting participants with maintaining or modifying their individualized healthy lifestyle plan. SBP Participants also received mail-out reminders of diet, physical activity, and stress managements facts previously learned during the 3-month DPP-LI weight loss program.

The primary objective was for participants’ post-intervention weight change to be ≤3% of their pre-intervention mean weight (weight prior to initiating weight loss efforts) as recommended by Stevens, Truesdale, McClain, and Cai (2006). The primary outcome of weight (kg) was measured using an electronic scale (Tanita BWB800AS) at baseline and 6-month follow-up. The weights were measured and collected by trained community assessors according to standardized data collection protocols. Two weight measurements were taken twice of each participant at each assessment point, and the average of the two were used in analysis.

Statistical Analysis

For this study, baseline was defined as the time-point immediately following randomization of participants into the weight loss maintenance intervention. Differences in baseline characteristics of study participants by intervention group and by completion of prescribed sessions (i.e., those who completed at least half of all prescribed sessions versus those who did not) were examined using Fisher’s exact (categorical variables) and T (continuous variables) tests. Variables found to differ significantly between intervention groups were included as covariates in the logistic regression analysis. Blackwelder’s (1982) method was used to test for equivalence of pre- and post-intervention weights. Successful weight maintenance was defined as a participants’ 6-month post-intervention weight change remaining ≤ 3% of their pre-intervention mean weight (Stevens et al., 2006). A relative indifference ratio (RIR) was computed as the odds ratio for weight maintenance (Cook, 2002; Senn, 1999). Logistic regression was used to compute RIR estimates adjusted for sex and community organization. A likelihood ratio test (LRT) was used to compute a P value for the null hypothesis that RIR equaled unity. In all analyses, dropouts were assumed to have regained 0.3 kg per month as used in similar studies (Wing et al., 2006). Statistical tests were two-sided and considered significant at p≤0.05.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The pre-weight loss maintenance program characteristics of participants (n=144) who were randomized are shown in Table 2. There were significant differences between the study groups in sex (more females in the SBP group) and distribution across community organization. Although PLP participants were heavier, there was no statistically significant difference in mean weight.

Retention and Adherence

The retention of participants between interventions was comparable with 68% in PLP and 71% in SBP (Figure 1). Approximately 47% of PLP versus 58% of SBP participants completed at least half of their prescribed sessions; however, the 95% CI for the difference in proportions included zero. Of the baseline characteristics, community organization [χ2 (4, N=144) = 25.55, p<0.0001] and age [t (142) = −3.26, p=0.0014] were significantly associated with sessions completed across both intervention groups. Collectively, the two community health centers (KKV and KPHC) had the most number of participants (46%) who completed at least half of the sessions across the two intervention groups (mean age=45.1; SD=15.3). Older participants were more likely to complete at least half of the prescribed sessions (mean age=53.7; SD=12.4) compared to younger participants. There was no statistically significant difference between groups in mean baseline weights (kg) among the participants who dropped-out or failed to complete at least half of the prescribed sessions (mean ± SD; PLP=105±27, SBP=101±31, p=0.54).

Weight Loss Maintenance

Both interventions achieved statistically significant weight loss maintenance (p≤0.05) (Table 3). However, PLP participants were 2.5-fold (95% CI=0.84–7.2; LRT p=0.091) more likely to have maintained their pre-intervention weight than SBP (i.e., weight change ≤ 3% of their pre-intervention mean weight) (Table 4). Among the 76 (of the 144) participants who completed half or more (≥3) of their prescribed lessons, PLP participants were 5.1-fold (95% CI=1.1–24; LRT p=0.024) more likely to have maintained their pre-intervention weight compared to SBP participants (Table 5).

Table 3.

Mean Weight Gain at 6-Month Follow-up by Intervention Group

| Intervention Group* | M (SD) | 95% CI | Test for equivalent pre-post weight maintenance¶ |

|---|---|---|---|

| PILI Lifestyle Program (PLP) | 0.075kg (4.7) | (−1.0, 1.2) | Equivalent (p≤0.05) |

| Standard Behavioral Weight Loss Maintenance Program (SBP) | 0.581kg (2.7) | (−0.06, 1.2) | Equivalent (p≤0.05) |

Note: M = Mean; SD = standard deviation; CI = confidence interval.

Dropouts are assumed to have regained 0.3 kg per month.

Indifference region (3% mean baseline weight), ∆PLP=−3.20 to +3.20 kg, ∆SBP=−2.98 to +2.98 kg.

Table 4.

Participants who Maintained Baseline§ Weight at 6-Month Follow-up by Intervention Group

| Intervention Group* | PLP (N=72) |

SBP (N=72) |

|---|---|---|

| Successful Weight Maintenance¶ | 64 (52) | 60 (48) |

| Unsuccessful Weight Maintenance¶ | 8 (40) | 12 (60) |

| Adjusted RIR=2.5 (95% CI=0.84, 7.2; LRT p=0.0910)† | ||

Note. Data shown as n (row %).

Baseline= time point immediately following randomization into weight loss maintenance intervention.

Dropouts are assumed to have regained 0.3 kg per month.

Weight change was computed as participant’s weight at end of weight loss maintenance intervention (6–month follow-up) minus their weight at the beginning of weight loss maintenance intervention (baseline). Successful weight maintenance was defined as weight change remaining below the upper limit of the Δ indifference region (3% mean baseline weight), ΔPLP=−3.20 to +3.20 kg, ΔSBP=−2.98 to +2.98 kg.

Logistic regression model, RIR adjusted for sex and community organization.

Table 5.

Participants with High Attendance¥ who Maintained Baseline§ Weight at 6-Month Follow-up by Intervention Group

| Intervention Group | PLP (N=34) |

SBP (N=42) |

|---|---|---|

| Successful Weight Maintenance¶ | 31 (50) | 31 (50) |

| Unsuccessful Weight Maintenance¶ | 3 (21) | 11 (79) |

| Adjusted RIR=5.1 (95% CI=1.06, 24; LRT p=0.0239)† | ||

Note. Data shown as n (row %).

High attendance = completed at least half (≥3) of their prescribed intervention sessions.

Baseline= time point immediately following randomization into weight loss maintenance intervention.

Weight change was computed as participant’s weight at end of weight loss maintenance intervention (6–month follow-up) minus their weight at the beginning of weight loss maintenance intervention (baseline). Successful weight maintenance was defined as weight change remaining below the upper limit of the Δ indifference region (3% mean baseline weight), ΔPLP=−3.20 to +3.20 kg, ΔSBP=−2.98 to +2.98 kg.

Logistic regression model, RIR adjusted for sex and community organization.

Adverse Events

Potential medical adverse events were monitored throughout the trial and reviewed by the DSMB. No serious adverse events were determined to be due to the interventions.

Discussion

We found that both the PLP and SBP helped participants maintain their initial weight loss over a 6-month period. However, between-intervention comparison revealed that more PLP participants were better able to maintain their initial weight loss compared with SBP participants within a 6-month pilot intervention period. This difference in weight loss maintenance was considerably larger among participants who completed half or more of the prescribed intervention sessions. The PLP appears to be effective for Pacific Islanders (i.e., Native Hawaiians, Samoans, Chuukese, and Filipinos) in preventing weight regain after intentional weight loss, with much stronger effects noted for those who attended at least half or more of the sessions.

Our findings are consistent with the 6-month results of Wing and colleagues (1999; 2006) in which their interventions, designed to prevent weight regain, performed better than either a standard behavior intervention or non-intervention control in a period of only 6 months following initial weight loss. Over a longer period of time (12 to 18 months) their interventions continued to perform better than comparison groups. This gives us confidence that our pilot PLP will perform as well when expanded over a longer time period and when continued to be delivered by community-peer educators. Six months was sufficient to establish the preliminary effectiveness of the PLP for Pacific Islanders. Notwithstanding, a longer and more intense version of the PLP will likely yield better weight loss maintenance, since these factors have been shown to play an important role in controlling obesity (Perri & Corsica, 2002). Efforts are under way to expand the PLP into an 18-month weight loss maintenance intervention and to test its efficacy.

We employed a CBPR approach whereby community members served as co-researchers (with co-equal decision making) in all aspects of designing and testing the intervention; in delivering the interventions via community-peer educators within their respective communities; and in having community researchers collect baseline and outcome data based on standardized protocols. This degree of involvement by community researchers is reflected in the list of authors who contributed to this report. What is also noteworthy is that the interventions were delivered by community peer educators who ranged in experience from first-timers in delivering an intervention (from KULA and HM) to more experienced community health workers (from KOM, KKV, and KPHC). In a review of past studies that involved different group-led obesity interventions, no significant differences in weight loss outcomes could be identified between lay and professional group leaders (Anderson et al., 2009). Reviews of RCT studies with community health workers as interventionists find that they can improve health behavior outcomes because they are better able to relate to participants by making health education more culturally, ethnically, and geographically relevant (Gibbons & Tyus, 2007; Norris et al., 2006; Rowe et al., 2005; Walters & Simoni, 2002).

In examining what baseline characteristics of our participants were associated with better participation in the prescribed sessions, we found that the community organization, from which they were recruited and received the interventions, and age were associated with the number of sessions they received. The two community health centers of our CBPR partnership (KKV and KPHC), collectively, had the most participants across the two interventions who completed at least half of all the sessions. We are unable, with the data from our study, to ascertain why adherence to the prescribed sessions were higher for the community health centers, but it might have something to do with the fact that they regularly provide clinical care and health education. The older adults (compared to younger adults) in our study were also more likely to participate in at least half of the sessions. Again, we are unable to ascertain why this may be so from the data we collected. Notwithstanding, these findings suggest that different strategies, based on type of organization delivering the intervention and age, might be needed to ensure that participants of a lifestyle intervention are able to adhere to its prescribed sessions, given that such adherence has been associated with better weight loss maintenance outcomes in this study and others (Perri & Corsica, 2002).

It is important to note that many of the Pacific Islanders in our study, across the two intervention groups, were morbidly obese (BMI ≥ 40) at baseline, despite having just completed a 3-month weight loss intervention. Mau et al. found a significant reduction in weight, albeit modest, between baseline measures and 3-month follow-up (−1.8 kg) in the cohort of participants from which the participants of this study were recruited (Mau et al., 2010). Despite the modest weight loss among participants who entered into our weight loss maintenance study, those who were randomized into the PLP were less likely to regain their weight compared to those who were randomized to SBP. This finding points to the benefits of the PLP in preventing not only weight regain in people who lost excessive weight but perhaps its potential for preventing excessive weight accumulation over time in people most at risk for overweight and obesity.

Given the pilot nature of our study, there are methodological limitations. Our “per protocol” results, analyzing only participants who completed at least half (≥3) of their lesson plans, must be interpreted cautiously. Departure from an intention-to-treat principle distorts the randomization process and may lead to unintended bias and counterintuitive results such as Simpson’s paradox (i.e., the success observed in different groups can be reversed when the groups are combined; Wagner, 1982). It is possible that participants who dropped out or failed to complete at least half of their lesson plans were more resistant to intervention; however, there was no statistically significant difference in their mean baseline weights. Furthermore, our intention-to-treat analysis also produced a positive relative odds estimate, although the effect size was lower than the “per protocol” result (i.e., 2.5 vs. 5.1). Finally, males (only 15%) were underrepresented in our study, which limits its generalizability to the larger Pacific Islander male population.

It is also worth noting that the mean weight at baseline differed between PLP and SBP participants, with those in the PLP being heavier on average. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.16). Furthermore, because we assessed weight loss maintenance based on the proportion of individuals who did not exceed a 3% increase in their baseline weight (i.e., the range was −3.20 to +3.20 kg for PLP versus −2.98 to +2.98 kg for SBP), the fact that the average mean weight between PLP and SBP participants were different at the start is not likely to have affected the observed outcomes. The successful weight loss maintenance measure we used (≤3% of initial weight) applied to both PLP and SBP participants.

Summary

Pacific Islanders are fast growing in the U.S. with continued immigration from Pacific Islands such as Western Samoa and the 6 U.S Affiliated Pacific Basin Jurisdictions (e.g., American Samoa, Guam, and Federated States of Micronesia; Grieco, 2000). Also on the rise in these populations are obesity and obesity-related disorders (e.g., diabetes) (Davis et al., 2004). Hence, culturally-relevant obesity interventions are much needed for Pacific Islanders. The PLP shows promise as an intervention to prevent excessive weight regain in Pacific Islanders. Because the PLP focuses on family and community factors that affect a person’s adoption and maintenance of healthy lifestyle changes, it also may show promise as an effective obesity intervention for other ethnic groups. Thus, the PLP warrants further examination in both Pacific Islanders and other ethnic populations. Finally, the use of a CBPR approach in designing, delivering, and testing the PLP and SBP interventions supports its strong applicability in both developing a culturally-relevant community based and led intervention and testing its efficacy via a RCT as well as its effectiveness in a real world setting.

Acknowledgements

We thank the PILI ‘Ohana Project participants, community researchers, and administration of the community organizations: Hawai‘i Maoli – The Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs, Ke Ola Mamo, Kula no nā Po‘e Hawai‘i, Kalihi-Pālama Health Center, and Kōkua Kalihi Valley Comprehensive Family Services. The community researchers were: Adrienne Dillard, JoHsi Wang, Andrea Siu, Andrea Macabeo, Alohanani Jamais, Keali‘i Lum, and Melaia Patu, Nafanua Braginski, Ruta Ene, Lucy Mefy, Regina Doone, Norma Pascua, Edna Higa, Millie Phillip, Joanna Jacob, Mildred Amaral, Miki Arume, Claire Townsend, Andrea H. Nacapoy, Sheri Kent, Natalie Hiratsuka, Sean Mosier, and Kā‘ohimanu Dang. This work was supported by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities [grant number R24MD001660] of the National Institutes of Health and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov [NCT01042886]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities or National Institutes of Health.

References

- Anderson L, Quinn T, Glanz K, Ramirez G, Kahwati LC, Johnson DB, et al. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(4):240–257. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.003. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Nicklas T, Thompson D, Baranowski J. Are current health behavioral change models helpful in guiding prevention of weight gain efforts? Obesity Research. 2003;11:23S–43S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.222. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwelder W. "Proving the null hypothesis" in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1982;3:345–353. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(82)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. Advanced statistics: Up with odds ratios! A case for odds ratios when outcomes are common. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2002;9:1430–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curioni CC, Lourenco PM. Long-term weight loss after diet and exercise: a systematic review. Internatioal Journal of Obesity. 2005;29(10):1168–1174. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803015. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EM, Clark JM, Carrese JA, Gary TL, Cooper LA. Racial and socioeconomic differences in the weight-loss experiences of obese women. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(9):1539–1543. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047050. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Busch J, Hammatt Z, Novotny R, Harrigan R, Grandinetti A, et al. The relationship between ethnicity and obesity in Asian and Pacific Islander populations: a literature review. Ethnicity and Disease. 2004;14(1):111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efird J, Bith-Melander P, Kimata C, Hong M, Jiang C, Baker K. Western Users of SAS Software. San Francisco: 2007. A SAS algorithm for blocked randomization. [Google Scholar]

- Elfhag K, Rossner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obesity Reviews. 2005;6(1):67–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandinetti A, Kaholokula JK, Theriault AG, Mor JM, Chang HK, Waslien C. Prevalence of diabetes and glucose intolerance in an ethnically diverse rural community of Hawaii. Ethnicity and Disease. 2007;17(2):250–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons MC, Tyus NC. Systematic Review of U.S.-Based Randomized Controlled Trials Using Community Health Workers. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2007;1(4):371–381. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0035. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco EM. The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Population: 2000: Census 2000 Brief. In: U.S. Census Bureau, editor. U.S. Department of Commerce. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Zimmet PZ. The Asia-Pacific Perspective: Redefining Obesity and Its Treatment. World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kaholokula JK, Saito E, Mau MK, Latimer R, Seto TB. Pacific Islanders' perspectives on heart failure management. Patient Educcation and Counseling. 2008;70(2):281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.015. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Christophi CA, Hoffman HJ, Brenneman AT, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1677–1686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK. Obesity treatment in minorities. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, editors. Handbook of Obesity Treatment. New York: Guilford; 2002. pp. 416–446. [Google Scholar]

- Martin K, Fontaine KR, Nicklas BJ, Dennis KE, Goldberg AP, Hochberg MC. Weight loss and exercise walking reduce pain and improve physical functioning in overweight postmenopausal women with knee osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2001;7(4):219–223. doi: 10.1097/00124743-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mau MK, Kaholokula JK, West M, Leake A, Efird JT, Rose C, et al. Translating Diabetes Prevention Research into Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities: The PILI 'Ohana Pilot Project. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2010;4(1):7–16. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0111. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mau MK, Sinclair K, Saito EP, Baumhofer KN, Kaholokula JK. Cardiometabolic health disparities in Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2009;31:113–129. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mau MK, Wong KN, Efird J, West M, Saito EP, Maddock J. Environmental factors of obesity in communities with native Hawaiians. Hawaii Medical Journal. 2008;67(9):233–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacapoy AH, Kaholokula JK, West MR, Dillard AY, Leake A, Kekauoha BP, et al. Partnerships to address obesity disparities in Hawai'i: the PILI 'Ohana Project. Hawaii Medical Journal. 2008;67(9):237–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Le K, Horsley T, Brownstein JN, Zhang X, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabetes Medicine. 2006;23(5):544–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01845.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Zhang X, Avenell A, Gregg E, Bowman B, Schmid CH, et al. Long-term effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in adults with pre-diabetes: a review. American Jounral of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(1):126–139. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.08.006. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri MG, Corsica JA. Improving the maitenance of weight lost in behavioral treatment of obesity. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, editors. Handbook of Obesity Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 357–379. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe AK, de Savigny D, Lanata CF, Victora CG. How can we achieve and maintain high-quality performance of health workers in low-resource settings? Lancet. 2005;366(9490):1026–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67028-6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn S. Rare distinction and common fallacy [letter] British Journal of Medicine. 1999 http://bmj.com/cgi/eletters/317/7168/1318. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J, Truesdale KP, McClain JE, Cai J. The definition of weight maintenance. International Journal of Obesity. 2006;30(3):391–399. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803175. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker JE, Tucker JA. Environmental events surrounding natural recovery from obesity. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22(4):571–575. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk MW, Yang K, Hravnak M, Sereika SM, Ewing LJ, Burke LE. Randomized clinical trials of weight loss maintenance: A review. Jounrnal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2009;24(1):58–80. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317471.58048.32. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317471.58048.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal J. Updated review on the benefits of weight loss. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2002;26(Suppl 4):S25–S28. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802215. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C. Simpson's paradox in real life. American Statistician. 1982;36:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion and Practice. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM. Reconceptualizing native women's health: an "indigenist" stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):520–524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. In: Bray GA, Bouchard C, editors. Handbook Obesity: Clinical Applications. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. pp. 147–167. [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. Journal of Consuting and Clinical Psychoogy. 1999;67(1):132–138. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(15):1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]