Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the role of higher order optical aberrations and thus retinal image degradation in the development of myopia, through the characterization of anisomyopia in human adults in terms of their optical and biometric characteristics.

Methods

The following data were collected from both eyes of fifteen young adult anisometropic myopes and sixteen isometropic myopes: subjective and objective refractive errors, corneal power and shape, monochromatic optical aberrations, anterior chamber depth, lens thickness, vitreous chamber depth, and best corrected visual acuity. Monochromatic aberrations were analyzed in terms of their higher order components, and further analyzed in terms of 31 optical quality metrics. Interocular differences for the two groups (anisomyopes vs. isomyopes) were compared and the relationship between measured ocular parameters and refractive errors also analyzed across all eyes.

Results

As expected, anisomyopes and isomyopes differed significantly in terms of interocular differences in vitreous chamber depth, axial length and refractive error. However, interocular differences in other optical properties showed no significant intergroup differences. Overall, higher myopia was associated with deeper anterior and vitreous chambers, higher astigmatism, more prolate corneas, and more positive spherical aberration. Other measured optical and biometric parameters were not significantly correlated with spherical refractive error, although some optical quality metrics and corneal astigmatism were significantly correlated with refractive astigmatism.

Conclusions

An optical cause for anisomyopia related to increased higher order aberrations is not supported by our data. Corneal shape changes and increased astigmatism in more myopic eyes may be a by-product of the increased anterior chamber growth in these eyes; likewise, the increased positive spherical aberration in more myopic eyes may be a product of myopic eye growth.

Keywords: Refractive error, anisomyopia, optical aberrations, spherical aberration, optical quality metrics, vitreous chamber depth, corneal asphericity

Introduction

Myopia is an ocular disease resulting from the mismatch between the eye’s refractive power and its dimensions. In a myopic eye, distant objects are focused before the retina and the retinal images blurred in the absence of appropriate optical correction. While any one of a number of ocular abnormalities can lead to myopia, i.e., the curvatures of the corneal and crystalline lens surfaces, refractive index gradient of the crystalline lens, anterior and vitreous chamber depth,1 increases in the latter component can largely explain most myopia.2, 3 Although the debate over the relative importance of “nature versus nurture” has not been settled,4, 5 it is generally accepted that both genes and environment are important in the development of myopia. The rising prevalence of myopia world-wide appears to be linked to increasing emphasis on education, adding strength to the nearwork hypothesis for myopia favoured by many6–8 although recent studies showing a protective effect of outdoor activity have also argued for a role of light.9–11

None of these ideas provides a ready explanation for anisomyopia (anisometropic myopia), which may accompany the development of myopia. Although significant population differences in prevalence figures for anisomyopia are apparent from reports in the literature,12–15 increases in anisomyopia in parallel with myopia progression is a common finding.13, 15 In these cases, the two eyes belong to the same individual, and so are presumably subject to similar genetic and environmental influences. Thus it seems reasonable to assume that the risk factors for anisometropia are local ones, differing in the two eyes of the same individual. Yet the identity of these risk factors remains allusive. Intraocular pressure has been the target of two relevant studies, which both yielded negative results; no significant interocular difference in intraocular pressure was observed in a study of anisometropic Chinese children,16 bearing out the conclusion from an earlier study of subjects with unilateral high myopia by Bonomi17 that ocular hypertension was neither caused by nor the cause of the high myopia. Nonetheless, attempts to fully characterize this condition have been limited, although Logan18 showed anisomyopia to be axial in nature, with the more myopic eyes being more elongated, with a more prolate shape deduced from peripheral (off-axis) refractive error measurements.

Animal studies have convincingly demonstrated the importance of retinal image quality for normal eye growth,3, 19 with myopic changes in response to retinal image degradation being a consistent finding across a range of animal species. However, typical experiments involve the imposition of large amounts of optical defocus (with lenses) or severe form deprivation (with diffusers or occluders), leading to inevitable questions about their relevance to human myopia.20 However, in a more recent study, we reported that the rate of vitreous chamber elongation in young chicks raised under normal conditions is partly predicted by the optical quality of their eyes as represented by optical quality metrics based on the eye’s monochromatic aberrations.21 Furthermore, while a role for astigmatism as the stimulus for increased myopia progression and anisomyopia is not supported by published data,14, 22, 23 studies investigating the role of ocular monochromatic aberrations in human myopia report associations in some,24, 25 albeit not in all cases.26, 27 Note in these studies, analyses of monochromatic aberrations were limited to traditional representations of aberrations (i.e., root mean squares, RMS). We argue that optical quality metrics for the eye28–31 may be more appropriate for studies in which the influence of aberrations on retinal image quality is salient.

The purpose of the current study was to investigate the optical and biometric characteristics of adult human anisomyopia, our working hypothesis being that retinal image quality degradation caused by higher order aberrations may cause anisomyopia. We also collected data from isomyopes for comparison, and used both RMS of Zernike coefficients and optical quality metrics to represent optical aberration data.28 To our knowledge, the detailed optical characterization of anisomyopia has not been previously reported. Preliminary results have been presented previously in abstract form.32

Methods

Subjects

The study was approved by the University of California Berkeley Committee for Protection of Human Subject and conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. College student volunteers were recruited to participate in the study by approved flyers and written informed consent was obtained from every subject. Based on a questionnaire survey, those with histories of ocular diseases, refractive surgeries and rigid contact lens wear were excluded. Thirty-one volunteers were accepted into the study. Their profiles are summarized in Table 1. They included 15 anisometropic myopes (anisomyopes) and 16 isometropic myopes (isomyopes), classified according to interocular differences in their spherical refractive errors (SRE = sphere + cylinder/2), derived from subjective refraction data. Subjects recording interocular differences in SRE greater than 1 D were classified as anisomyopes; those with interocular differences in SRE less than or equal to 1 D were classified as isomyopes. Astigmatic refractive errors were within 2.1 D for all subjects. All accepted subjects also had best corrected visual acuities of better than 0.1 logMAR (Snellen equivalent 6/7.5 or 20/25).

Table 1.

Profile of young adult participants in this study.

| Parameter | Property | Anisometropia (ASO) (n = 15) |

Isometropia (ISO) (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification criterion | ΔSRE (D)# | |ΔSRE| > 1 | |ΔSRE| ≤ 1 |

| Spherical refractive error (SRE,# D) |

Mean ± SD (Range) |

LME*: −3.29±2.17 (0.19 to −6.51) MME: −4.83±2.21 (0.05 to −7.85) |

−3.76±2.45, (+0.11 to −7.05) |

| Ethnicity | Asian Caucasian Other $ |

8 5 2 |

8 5 3 |

| Gender | Male Female |

7 8 |

8 8 |

| Age (years) | Mean ± SD (Range) |

23.87±3.52 (19 to 30) |

22.34±3.28 (17 to 29) |

Spherical refractive error, calculated as Sphere + Cylinder/2; Δ =interocular difference

LME: least myopic eye, MME: more myopic eye

includes Hispanic, African American and Arab.

Ocular measurements

Because of the age of the subjects – young adults – testing was performed without cycloplegia. Measurements included objective and subjective refractions, best-corrected visual acuity, and corneal topography. Right eyes were always measured before left eyes. A Grand Seiko WR-5100K autorefractor (http://www.grandseiko.com/english/WR-5100K.htm) was used to collect objective refraction data;33 subjects were instructed to look at a distant target (> 6 m) and 5 readings recorded in quick succession. Subjective refractive errors were measured by one of the authors, JT, an experienced optometrist, and used along with a Bailey-Lovie eye chart in measurements of best-corrected visual acuity in logMAR.34 Corneal power and shape information was derived from topography data collected with a Humphrey Atlas corneal topographer (Carl Zeiss, Dublin, CA). Four recordings were taken for each eye. Simulated K-values for the two principal meridians and a corneal shape factor, also referred to as corneal asphericity,35 are reported. Biometric measurements were carried out last, using a Mentor Ophthalmic A-scan ultrasound biometer (Mentor Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA), which provided anterior chamber depth, lens thickness and total axial length data. Five readings were recorded for each eye, with the subjects viewing a distant target at 4 m.

Aberration data were collected in a follow-up measurement session on another day. Here also, right eyes were measured before left eyes. In the interest of fully characterizing the optical aberrations of our subjects’ eyes, their pupils were first dilated, using one to two drops of topical 1% tropicamide solution (EyeMyd, Bausch & Lomb, Tampa, FL), following local anaesthesia with one drop of 0.5% proparacaine solution (Wilson Ophthalmic, Mustang, OK). Monochromatic aberrations were measured using a Shack-Hartmann aberrometer (Wavefront Sciences, Albuquerque, NM) operating at 840nm.36 Subjects was instructed to look at an optically distant target displayed in the aberrometer and keep their eyes open wide for this measurement. A set of five readings were recorded, each 1–2 seconds after a blink.

Data analyses

Where multiple readings were taken from each eye, their average was derived for use in subsequent analyses, and in the case of refractive errors and simulated K-values, readings were converted to power vectors prior to the averaging process.37 While vitreous chamber depth could not be recorded directly with our biometer, it was derived by subtracting anterior chamber depth and lens thickness from the total axial length.

Optical Society of America standard Zernike polynomials were used to analyze and represent monochromatic aberrations.38 In healthy human eyes, the Zernike coefficients become progressively smaller for higher order terms, and thus analyses are typically limited to the 2nd to 6th order terms.39–41 In the current study, we limited analyses to the most significant, 2nd to 5th order terms, and a pupil diameter of 5 mm. The three 2nd order terms describe the refractive error,42, 43 and the 3rd to 5th order terms are classified as higher order aberrations (HOAs). To facilitate more intuitive interpretation of our results, HOAs are specified in terms of equivalent defocus power (EDP), defined as

| (1) |

where RMS is the root mean squares (RMS) of HOAs, and r is the radius of the analyzed pupil. Spherical aberration data represent an exception here, with the Zernike coefficient being used instead of the RMS value in deriving EDP values to preserve its sign.43

Because of the unequal contributions of different monochromatic aberrations to the total aberrations and the interactions between them,29, 30 the magnitude of ocular HOAs, i.e. the RMS of Zernike coefficients or EDP value, is not a good indicator of their visual impact. On the other hand, optical quality metrics, derived from optical aberrations, have this intended purpose. Of the described alternatives, some have been found to capture the effects of aberrations on visual perception,28, 31, 42, 44 and some predict eye growth in young chicks under normal viewing conditions.21 Here we used 31 previously studied optical quality metrics to evaluate the effects of the HOAs of our subjects. Ten of these metrics are directly based on the quality of the reconstructed wavefront, 11 of them are based on point spread functions, and the other 10 are based on optical transfer functions (OTFs) or modulation transfer functions (MTFs). Simple descriptions of these optical quality metrics are summarized in an Appendix; more detailed descriptions are provided in an earlier paper.42

The correlations between refractive errors and the various optical and biometric parameters were computed using pooled data from both eyes of all subjects (n=62 eyes). It should be noted that the two eyes of the same subjects were treated as independent samples, as in a published, related study.42 The occurrence of anisometropia is presented as evidence against the assumption that the ocular dimensions of the two eyes of individual subjects are correlated, although it does not rule out the possibility of significant interocular correlations, particularly for isometropes. For each optical quality metric, values from the 62 eyes were standardized by computing Z-scores

| (2) |

where i=1,2,…‥62. This procedure results in relative, unitless optical quality metric values that can be compared easily across different optical quality metrics. The statistical significance of the correlations was tested using a t-test with (n−2) degrees of freedom and a special t-statistic

| (3) |

where r is the correlation coefficient and n is the sample size45. As appropriate, interocular differences in recorded and derived parameters were calculated and values for anisomyopes and isomyopes compared. Differences were expressed as absolute values for these comparisons. All computations and statistical analyses were carried out in commercial software Matlab (Math Works, Natick, MA) and open source software R (www.r-project.org).

Results

Refractive errors measured by subjective & objective methods, & derived from optical aberrations

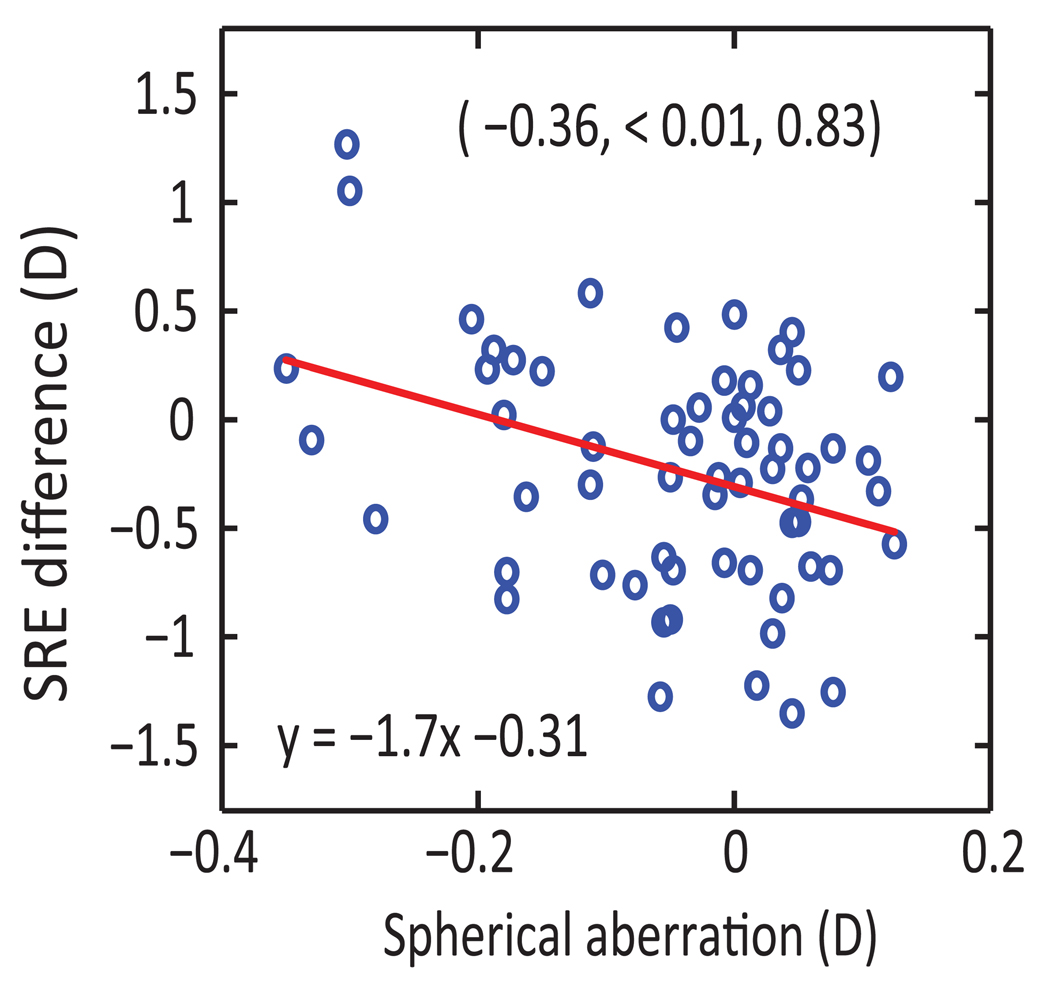

Spherical refractive errors (SREs) measured by subjective refraction are highly correlated with both objective refraction (autorefraction) results (r = 0.98, p < 0.01) and those derived from aberrometry data (r = 0.98, p < 0.01). However, there are discrepancies between subjective and autorefraction-derived SREs for some eyes and these discrepancies are significantly correlated with spherical aberration (r = −0.36, p < 0.01; Figure1). Refractive astigmatism (cylindrical refractive error, CRE) measured with the subjective and objective methods are also significantly correlated, although the correlations are not as tight as those between SREs (subjective refraction vs. autorefraction: r = 0.83, p < 0.01, subjective refraction vs. aberrometry: r = 0.86, p < 0.01). In following sections, only results from analyses using aberrometry-derived refraction data are reported, unless specifically stated.

Figure 1.

Differences between subjective and autorefractor-based spherical refractive errors (SRE) plotted against spherical aberration (n = 62 eyes). Correlation coefficient (r), the corresponding p-value (p) and statistical power (pwr) from statistical analysis are shown as (r, p, pwr) in the graph. The equation for the linear regression line is also shown.

Relationships between refractive errors & optical and biometric parameters

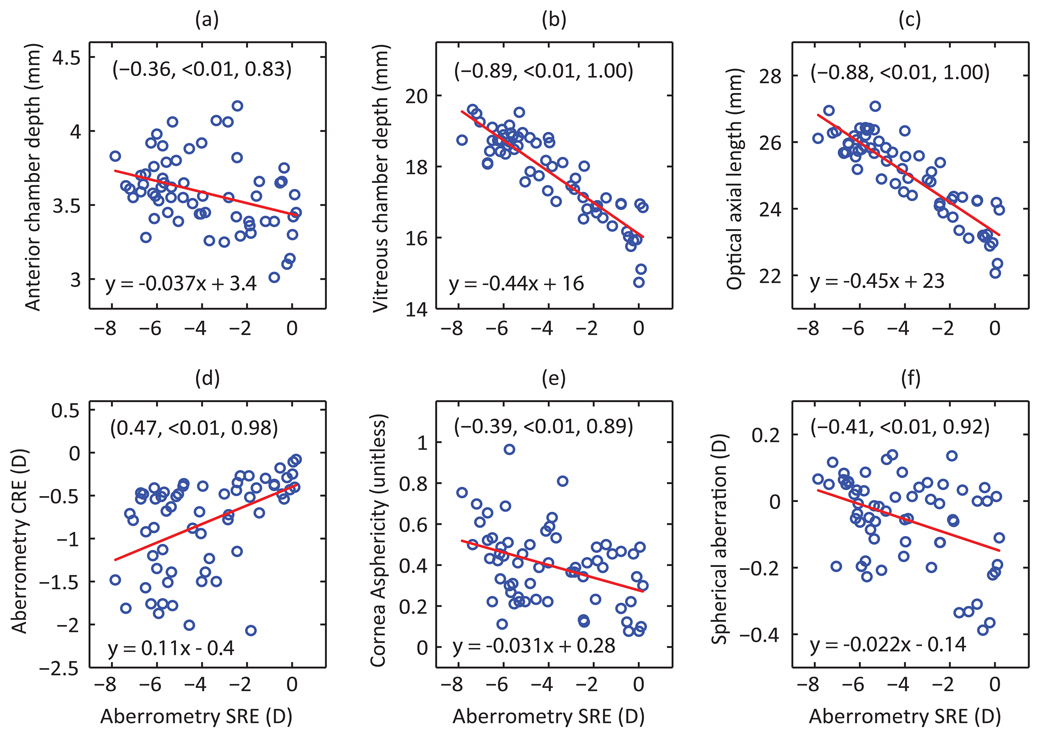

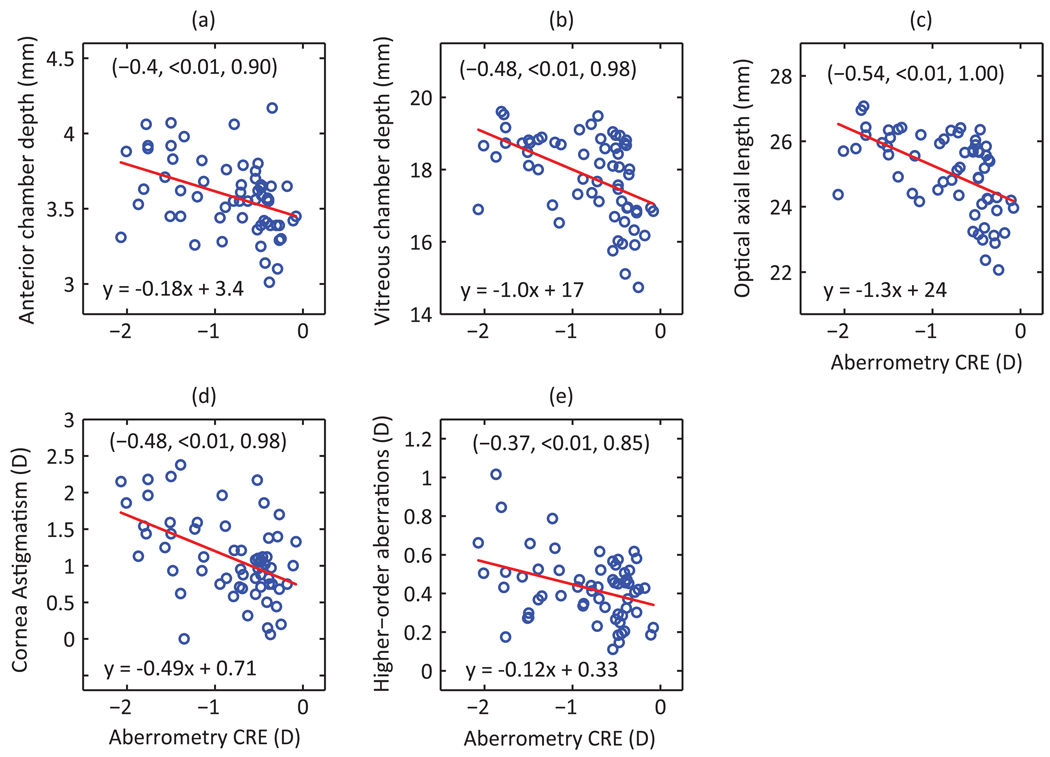

More myopic eyes tended to have higher CRE, more prolate corneas and longer eyes, with both the anterior and vitreous chambers contributing to the latter. Figure 2 graphically depicts the relationships between measured biometric and optical parameters and SREs; similar graphical analyses are shown for CREs in Figure 3. The axial origin of the myopia in our subjects is reflected in the strong correlation between SRE and both vitreous chamber depth and axial length (r = −0.89, −0.88 respectively, p < 0.01). The contribution of anterior chamber depth to differences in axial length and thus myopia is much smaller, around 12%, but nonetheless the correlation between SRE and anterior chamber depth is statistically significant (r = −0.36, p <0.01). SRE is also significantly correlated with both corneal asphericity (r = −0.39, p < 0.01), and CRE (r = 0.47, p < 0.01), the latter being significantly correlated with anterior chamber depth (r = −0.4, p < 0.01). As expected, CRE and corneal astigmatism are also well correlated (r = −0.48, p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Spherical refractive errors (SREs) plotted against measured biometric (a–c) and optical (d–f) parameters (n = 62 eyes). Included are the equations for linear regression lines and corresponding correlation coefficients, p-values and statistical powers (shown in same order in brackets).

Figure 3.

Aberrometry-based refractive astigmatism (CRE), plotted against measured biometric (a–c) and optical (d–e) parameters (n = 62 eyes). Included are the equations for linear regression lines and corresponding correlation coefficients, p-values and statistical powers (shown in same order in brackets).

With respect to optical aberrations, more myopic eyes exhibited more positive spherical aberration but HOAs were not increased. Thus the correlation between SRE and spherical aberration is significant (r = −0.41, p < 0.01) but not the correlation between SRE and HOAs, although HOAs and CRE are significantly correlated (r = −0.37, p < 0.01). None of the 31 optical quality metrics analyzed show significant correlations with SRE; although there are two cases where the p-values indicate statistical significance, the power of the test is less than 0.80 (Table 2). In contrast, seven of these metrics show significant correlations with CRE (p<0.01; Table 2). Of the latter seven optical quality metrics, three of them (standard deviation of the PSF, Visual Strehl ratio computed using OTF and Visual Strehl ratio computed using MTF) were among the best predictors of visual performance in a previous study28 with R-squared better than 0.5.

Table 2.

Results of correlation analyses of the relationship between optical quality metrics and refractive errors (spherical refractive error (SRE) and refractive astigmatism (CRE)).

| Categoy & abbreviated names of optical quality metrics |

Correlation with SRE | Correlation with CRE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient |

p-value (power) | Correlation coefficient |

p-value (power) | ||

| Wavefront-based | RMSw | −0.13 | 0.15 | −0.69 | < 0.01 (1.00) |

| PV | −0.15 | 0.13 | −0.45 | < 0.01 (0.96) | |

| RMSs | −0.24 | 0.03 (0.47) | −0.42 | < 0.01 (0.93) | |

| Bave | −0.05 | 0.35 | 0.025 | 0.42 | |

| PFWc | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.50 | < 0.01 (0.99) | |

| PFSc | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.15 | |

| PFCc | −0.01 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.47 | |

| PFWt | −0.06 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.32 | |

| PFSt | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.42 | |

| PFCt | −0.01 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.42 | |

| PSF-based | D50 | −0.03 | 0.41 | −0.07 | 0.29 |

| EW | −0.04 | 0.39 | −0.11 | 0.19 | |

| SM | −0.10 | 0.23 | −0.12 | 0.17 | |

| HWHH | −0.03 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.45 | |

| CW | −0.05 | 0.36 | −0.14 | 0.13 | |

| SRX | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.27 | |

| LIB | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.24 | |

| STD | 0.27 | 0.02 (0.57) | 0.65 | < 0.01 (1.00) | |

| ENT | 0.01 | 0.46 | −0.16 | 0.11 | |

| NS | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.27 | |

| VSX | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.27 | |

| OTF/MTF-based | SFcMTF | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.20 |

| SFcOTF | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.27 | |

| AreaMTF | −0.03 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.43 | |

| AreaOTF | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.43 | |

| SRMTF | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.47 | |

| SROTF | −0.04 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.35 | |

| VSMTF | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.38 | < 0.01 (0.87) | |

| VSOTF | 0.21 | 0.05 (0.38) | 0.38 | < 0.01 (0.87) | |

| VOTF | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.20 | |

| VNOTF | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.18 | |

Interocular differences in anisomyopes and isometropes

Mean interocular difference data for the various measured parameters are summarized in Table 3 for the anisomyopic and isomyopic groups. Mean differences in SRE were 1.73 ±0.67 D and 0.14 ±0.27 D for the anisomyopes and isomyopes respectively. The latter group difference is highly significant (p<0.01). However, of the other measured parameters, only interocular differences in vitreous chamber depth and optical axial length show significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.01). Interocular differences in CRE for the two groups are not significantly different (p = 0.43).

Table 3.

Interocular differences in various ocular parameters for anisomyopes and isometropes.

| Parameter | Anisomyopes (Mean ± SD; n=15) |

Isometropes (Mean ± SD; n=16) |

p-values of inter-group differences (power) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical refractive error (D) | 1.73±0.67 | 0.14± 0.27 | <0.01 (1.000) |

| Refractive astigmatism (D) | 0.17±0.30 | 0.09± 0.25 | 0.43 |

| Best corrected visual acuity (logMAR) | −0.016±0.073 | 0.008± 0.036 | 0.26 |

| Anterior chamber depth (µm) | −72±121 | 24±189 | 0.05 (0.485) |

| Lens thickness (µm) | 1±86 | −38±130 | 0.34 |

| Vitreous chamber depth (µm) | −507±385 | 91±221 | <0.01 (0.999) |

| Axial length (µm) | −579±410 | 77±251 | <0.01 (1.000) |

| Horizontal simulated K-value (D) | 0.05±0.49 | −0.28±0.74 | 0.16 |

| Vertical simulated K-value (D) | −0.06±0.63 | −0.12±0.59 | 0.79 |

| Corneal astigmatism (D) | 0.10±0.33 | −0.11±0.73 | 0.31 |

| Corneal asphericity (unitless) | −0.046±0.222 | −0.007±0.086 | 0.53 |

| Spherical aberration Z(4,0)# (D) | 0.019±0.075 | 0.008±0.128 | 0.77 |

| 3rd order higher order aberrations# (D) | −0.038±0.179 | 0.076±0.199 | 0.11 |

| 4th order higher order aberrations# (D) | −0.031±0.059 | −0.010±0.191 | 0.68 |

| 5th order higher order aberrations# (D) | −0.027±0.092 | −0.061±0.130 | 0.41 |

| Total higher order aberrations# (D) | −0.053±0.185 | 0.032±0.289 | 0.34 |

| Mean optical quality metrics$ | −0.018±0.119 | 0.016±0.151 | 0.14 |

Aberrations are represented in Equivalent Defocus Power (EDP) as defined in Equation 1. The total higher order aberrations are the root mean square (RMS) sum of 3rd to 5th order higher order aberrations.

The means and SDs are the average of 10 optical quality metrics that consider only 3rd to 5th order higher order aberrations; for these optical quality metrics, p-values for the t-tests on interocular differences were at least 0.14.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the optical and biometrical characteristics of the two eyes of young adult anisomyopes, and for additional comparison, also included isomyopes. Significant intergroup differences were limited to anterior chamber depth, vitreous chamber depth and optical axial length with respect to interocular differences, although anterior chamber depth, corneal asphericity and spherical aberration were strongly correlated with SRE overall. With the exception of spherical aberration, HOAs, represented either in terms of EDP or optical quality metric values, were not correlated with SRE. The implications of these results for the aetiology of human myopia and anisomyopia are discussed below.

Relationship between refractive errors and HOAs

The main motivation for this study was to investigate the role of ocular monochromatic aberrations in the development of myopia. We rationalized that a study of anisomyopes would provide improved sensitivity, by minimizing environmental influences. However, we did not find interocular differences in aberrations to which to causally attribute the interocular differences in refractive error of our anisomyopes. Further, two recent studies in chick suggest that subtle retinal image degradation may not be sufficient to trigger myopic growth. In one study, corneal refractive surgery resulted in transient image degradation but did not induce myopia,46 and in the second study, diffusing filters used to induce form deprivation were shown to be without effect on eye growth except when most spatial information was removed.47

As an alternative, perhaps more sensitive, approach to addressing the same question of whether monochromatic aberrations underlie the development of myopia, we derived from our aberration data (3rd to 5th HOAs), 31 different optical quality metrics, some of which have been previously shown to be good predictors of visual performance.28,31,42,44 While no significant correlations were found between these optical quality metrics and SRE (Table 2), seven of the derived optical quality metrics were significantly correlated with CRE, of which three (standard deviation of the PSF, Visual Strehl ratio computed using OTF and Visual Strehl ratio computed using MTF) were previously shown to be good predictors of visual performance.28 It is interesting to note that more astigmatic eyes also had deeper anterior chambers. Thus it is plausible that their corneas were more vulnerable to lid moulding, thereby contributing to the HOAs and poorer optical quality of these eyes.48 Although only a relatively small number of eyes (n=62) was used for the current optical quality metrics analyses, the pattern of the correlation matrix of different optical quality metrics is very similar to that from a previous study based on a large population (200 eyes).42

Our finding of more positive spherical aberration in more myopic eyes is consistent with results of an earlier study of myopic children,49 and predictions based on an eye model26 while some other studies report no correlation between spherical aberration and refractive error,26, 50, 51 and still others report the opposite trend, i.e. that myopes have less positive spherical aberration compared to emmetropes.52–54 Differences in corneal shape are likely to contribute to the trend reported here, as we found more myopic eyes also had more prolate corneas. However, the significance of these results for the aetiology of myopia remains unresolved. First, the cross sectional nature of all studies does not allow cause and effect to be distinguished. Second, spherical aberration undergoes a negative shift with increasing accommodation, due to aspheric changes in the crystalline lens;24, 55, 56. Whether the more positive spherical aberration found in more myopic eyes represents a risk factor for myopia is discussed further below.

Of relevance to the interpretation of data collected with autorefractors, we found a significant correlation between spherical aberration and the difference between subjective and objective refractions, which is consistent with previous empirical and modelling findings that spherical aberration influences the perceived best focus plane.44, 54, 57

The aetiology of human anisomyopia and myopia

Given that anisometropia frequently manifests as a developmental phenomenon,58 we hypothesized that local risk factors were likely involved, that is, those that affect one rather than both eyes of an individual. In our search for local risk factors, we systematically compared interocular differences in the most important and easily accessible optical and biometric parameters for anisomyopes and isomyopes. However, the two eyes of our anisomyopes did not exhibit any optical differences, i.e., in corneal power, corneal shape (asphericity), or total HOAs, to which causality could be attributed. Significant intergroup differences in ocular dimensions were limited to vitreous chamber depth and optical axial length, the deeper vitreous chamber and longer optical axial length in the more myopic eyes of our anisomyopes being consistent with results from a previous study of anisomyopes,18 and the presumed product of an unidentified myopia-inducing stimulus.

If spherical aberration were a risk factor for myopia, we would expect anisomyopes to have larger interocular differences in spherical aberration than isomyopes, with more positive spherical aberration in their more myopic eye. While we did find significant correlation between SRE and spherical aberration, the isomyopic and anisomyopic groups exhibited similar interocular differences in spherical aberration. One possible explanation is insufficient sensitivity, given that the mean interocular SRE difference for the anisomyopic group was only 1.73 D. Further investigations with a large number of subjects of much greater interocular differences in SRE may provide a more conclusive answer to this question. A longitudinal study addressing the same question would also be more informative.

Summary & Conclusion

Among the optical and biometric parameters examined in this study, only vitreous chamber depth and optical axial length showed significantly greater interocular differences in anisomyopia than in isomyopia, consistent with the axial origin of the former condition. That intergroup differences were not observed for any of the measured optical parameters argues against an optical aetiology for anisomyopia. The observed correlation between spherical aberration and spherical refractive error, and other correlations between some of the optical quality metrics and refractive astigmatism may represent products of myopic growth, although a causal relationship cannot be totally ruled out.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grant NEI R01 EY12392 (CFW) and NEI T32 EY070043 (JMT) from the National Eye Institute, and University of California Regents Graduate Fellowship (to YT). The authors thank Dr. Nina Tran for the help in data collection.

Appendix

Optical Quality Metrics$

| Category | Name | Description | Property# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavefront-based | RMSw | Root mean squared wavefront error computed over analyzed pupil | N |

| PV | Peak to valley magnitude of wavefront | N | |

| RMSs | Root mean squared wavefront slope computed over analyzed pupil | N | |

| Bave | Average blur strength | N | |

| PFWc | Pupil fraction when critical pupil is the concentric area where RMSw is smaller than a criterion | P | |

| PFSc | Pupil fraction when critical pupil is the concentric area where RMSs is smaller than a criterion | P | |

| PFCc | Pupil fraction when critical pupil is the concentric area where Bave is smaller than a criterion | P | |

| PFWt | Pupil fraction when a good subaperture is where PV is smaller than a criterion | P | |

| PFSt | Pupil fraction when a good subaperture is where wavefront slopes are smaller than a criterion | P | |

| PFCt | Pupil fraction when a good subaperture is where Bave is smaller than a criterion | P | |

| PSF-based | D50 | Diameter of circular area centred on PSF peak that captures 50% of energy in PSF | N |

| EW | Equivalent width of cantered PSF | N | |

| SM | Square root of 2nd moment of PSF | N | |

| HWHH | Half width at half height of PSF | N | |

| CW | Correlation width of PSF | N | |

| SRX | Strehl ratio computed using PSF | P | |

| LIB | Light in bucket (bucket is diffraction-limited PSF) | P | |

| STD | Standard deviation of PSF, normalized by diffraction-limited value | P | |

| ENT | Entropy of PSF | N | |

| NS | Neural sharpness | P | |

| VSX | Visual Strehl ratio computed using PSF | P | |

| OTF/MTF-based | SFcMTF | Spatial frequency cut-off of radial MTF | P |

| SFcOTF | Spatial frequency cut-off of radial OTF | P | |

| AreaMTF | Area of radial MTF, normalized by diffraction-limited value | P | |

| AreaOTF | Area of radial OTF, normalized by diffraction-limited value | P | |

| SRMTF | Strehl ratio computed using MTF | P | |

| SROTF | Strehl ratio computed using OTF | P | |

| VSMTF | Visual Strehl ratio computed using MTF | P | |

| VSOTF | Visual Strehl ratio computed using OTF | P | |

| VOTF | Volume under OTF, normalized by volume under MTF | P | |

| VNOTF | Volume under neutrally-weighted OTF, normalized by volume under neutrally-weighted MTF | P |

Detailed descriptions of the optical quality metrics was provided by Thibos et al. (2004).42

P indicates that higher values represent better optical quality; N indicates that higher values represent worse optical quality.

References

- 1.Curtin B. The Myopias: Basic Science and Clinical Management. Philadelphia: Harper and Row; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wildsoet C. Structural correlates of myopia. In: Rosenfield M, Gilmartin B, editors. Myopia and Nearwork. New York: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1998. pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallman J, Winawer J. Homeostasis of eye growth and the question of myopia. Neuron. 2004;43(4):447–468. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutti D, Zadnik L, Adams A. Myopia: the nature versus nurture debates goes on. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:952–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dirani M, Chamberlain M, Shekar S, Islam A, Garoufalis P, Chen C, et al. Heritability of refractive error and ocular biometrics: the genes in myopia (GEM) twin study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4756–4761. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams A. Working Group on Myopia Prevalence and Progression. Myopia: Prevalence and Progression. Washington: National Academy Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goss D. Nearwork and myopia. Lancet. 2000;356:1456–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02864-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ip J, Saw S, Rose K, Morgan I, Kifley A, Wang J, et al. Role of near work in myopia: findings in a sample of Australian school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;49:2903–2910. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones L, Sinnott L, Mutti D, Mitchell G, Moeschberger M, Zadnik K. Parental history of myopia, sports and outdoor activities, and future myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3524–3532. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose K, Morgan I, Ip J, Kifley A, Huynh S, Smith W, et al. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1279–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dirani M, Tong L, Gazzard G, Zhang X, Chia A, Young T, et al. Outdoor activity and myopia in Singapore teenage children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:997–1000. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.150979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laird I. Anisometropia. In: Grosvenor T, Flom MC, editors. Refractive Anomalies: Research and Clinical Applications. London: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1991. pp. 174–198. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen S, Lin L, Hsiao C, Shih Y, Hung P, editors. The prevalence of anisometropia among schoolchildren in Taiwan. 9th International Conference on Myopia; Hong Kong and Guangzhou. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldschmidt E, Lyhne N, Lam C. Ocular anisometropia and laterality. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004;82:175–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2004.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fesharaki H, Kamali B, Karbasi M, Fasihi M. Development of myopia in medical school. Asian J Ophthalmol. 2006;8:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S, Edwards M. Intraocular pressure in anisometropic children. Optom Vis Sci. 2000;77:675–679. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200012000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonomi L, Mecca E, Massa F. Intraocular pressure in myopic anisometropia. Int Ophthalmol. 1982;5:145–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00149143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logan N, Gilmartin B, Wildsoet C, Dunne M. Posterior retinal contour in adult human anisomyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2152–2162. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wildsoet C. Active emmetropization--evidence for its existence and ramifications for clinical practice. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1997;17(4):279–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zadnik K, Mutti D. How applicable are animal myopia models to human juvenile onset myopia? Vision Res. 1995;35:1283–1288. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00234-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian Y, Tran N, Wildsoet CF. Optical quality metrics can predict eye growth. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48 E-Abstract 4004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pärssinen O, Hemminki E, Klemetti A. Effect of spectacle use and accommodation on myopic progression: final results of a three-year randomised clinical trial among schoolchildren. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:547–551. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.7.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin S, Tsai C, Shih Y, Lin L, Hung P. The relationship between astigmatism to progression of myopia. The VIII International Conference on Myopia; Boston. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins M, Wildsoet CF, Atchison D. Monochromatic aberrations and myopia. Vision Res. 1995;35:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00236-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carkeet A, Dong L, Tong L, Saw S, Tan D. Refractive error and monochromatic aberrations in Singaporean children. Vision Res. 2002;42:1809–1824. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng X, Bradley A, Hong X, Thibos L. Relationship between refractive error and monochromatic aberrations of the eye. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:43–49. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charman W. Aberrations and myopia. Ophthal Physl Opt. 2005;25:285–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsack J, Thibos L, Applegate R. Metrics of optical quality derived from wave aberrations predict visual performance. J Vision. 2004;4:322–328. doi: 10.1167/4.4.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Applegate R, Sarver E, Khemsara V. Are all aberrations equal? J Refract Surg. 2002;18:S556–S562. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20020901-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Applegate R, Ballentine C, Gross H, Sarver E, Sarver C. Visual acuity as a function of Zernike mode and level of root mean square error. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:97–105. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen L, Singer B, Guirao A, Porter J, Williams D. Image metrics for predicting subjective image quality. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:358–369. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000162647.80768.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian Y, Tarrant J, Wildsoet C. Optical and biometric bases of anisomyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47 doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1211. E-Abstract 3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies L, Mallen E, Wolffsohn J, Gilmartin B. Clinical evaluation of the Shin-Nippon NVision-K 5001/Grand Seiko WR-5100K. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:320–324. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200304000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bailey I, Lovie J. New design principles for visual acuity letter charts. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1976;53:740–745. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeandervin M, Barr J. Comparison of repeat videokeratography: repeatability and accuracy. Optom Vis Sci. 1998;75:663–669. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199809000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng X, Himebaugh N, Kollbaum P, Thibos L, Bradley A. Validation of a clinical Shack-Hartmann aberrometer. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:587–595. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200308000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thibos L, Wheeler W, Horner D. Power vectors: an application of Fourier analysis to the description and statistical analysis of refractive error. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:367–675. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199706000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thibos L, Applegate R, Schwiegerling J, Webb R. Standards for reporting the optical aberrations of eyes. J Refract Surg. 2002;18:S652–S660. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20020901-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thibos L, Hong X, Bradley A, Cheng X. Statistical variation of aberration structure and image quality in a normal population of healthy eyes. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2002;19:2329–2348. doi: 10.1364/josaa.19.002329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castejon-Mochon J, Lopez-Gil N, Benito A, Artal P. Ocular wave-front aberration statistics in a normal young population. Vision Res. 2002;42:1611–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porter J, Guirao A, Cox I, Williams D. Monochromatic aberrations of the human eye in a large population. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2001;18:1793–1803. doi: 10.1364/josaa.18.001793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thibos L, Hong X, Bradley A, Applegate R. Accuracy and precision of objective refraction from wavefront aberrations. J Vision. 2004;4:329–351. doi: 10.1167/4.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian Y, Wildsoet CF. Diurnal fluctuations and developmental changes in ocular dimensions and optical aberrations in growing chick eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4168–4178. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng X, Bradley A, Thibos L. Predicting subjective judgment of best focus with objective image quality metrics. J Vision. 2004;4:310–321. doi: 10.1167/4.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowry R. [cited 2010];Concepts and Applications of Inferential Statistics. [Free on-line book] 1999 updated 1999; Available from: http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/webtext.html.

- 46.Tian Y, Arnoldussen M, Tuan A, Logan B, Wildsoet CF. Evaluation of retinal image degradation by higher-order aberrations and light scatter in chick eyes after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) J Mod Opt. 2008;55:805–818. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tran N, Chiu S, Tian Y, Wildsoet CF. The significance of retinal image contrast and spatial frequency composition for eye growth modulation in young chicks. Vision Res. 2008;48(15):1655–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Artal P, Guirao A. Contributions of the cornea and the lens to the aberrations of the human eye. Opt Lett. 1998;23:1713–1715. doi: 10.1364/ol.23.001713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He J, Sun P, Helda R, Thorna F, Sun X, Gwiazda J. Wavefront aberrations in eyes of emmetropic and moderately myopic school children and young adults. Vision Res. 2002;42:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atchison D, Schmid K, Pritchard N. Neural and optical limits to visual performance in myopia. Vision Res. 2006;46:3707–3722. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marcos S, Barbero S, Llorente L. The sources of optical aberrations in myopic eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43 E-Abstract 1510. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carkeet A, Velaedan S, Tan Y, Lee D, Tan D. Higher order ocular aberrations after cycloplegic and non-cycloplegic pupil dilation. J Refract Surg. 2003;19:316–322. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20030501-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwan W, Yip S, Yap M. Monochromatic aberrations of the human eye and myopia. Clin Exp Optom. 2009;92:304–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2009.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tarrant J, Roorda A, Wildsoet CF. Determining the accommodative response from wavefront aberrations. J Vision. 2010;10:4. doi: 10.1167/10.5.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng H, Barnett J, Vilupuru A, Marsack J, Kasthurirangan S, Applegate R, et al. A population study on changes in wave aberrations with accommodation. J Vision. 2004;4:272–280. doi: 10.1167/4.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koomen M, Tousey R, Scolnik R. The spherical aberration of the eye. J Opt Soc Am. 1949;39:370–376. doi: 10.1364/josa.39.000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian Y, Shieh K, Wildsoet CF. Performance of focus measures in the presence of nondefocus aberrations. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2007;24:B165–B173. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.00b165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weale R. On the age-related prevalence of anisometropia. Ophthalmic Res. 2002;34:389–392. doi: 10.1159/000067040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]