Abstract

Objectives.

This article examined exposure to and appraisal of care-related stressors associated with use of adult day services (ADS) by family caregivers of individuals with dementia.

Methods.

Using a within-person withdrawal design (A-B-A-B), we compared caregivers’ exposure to and appraisal of behavior problems on days their relative attended and did not attend ADS. Participants were 121 family caregivers enrolling a relative with dementia in an ADS program. Daily assessments were obtained prior to the person's attending ADS for the first time and after 1 and 2 months of attendance on days the person attended and did not attend ADS.

Results.

Total exposure to stressors and stress appraisals decreased significantly over time on ADS days compared with non-ADS days. Most of this difference was accounted by the time the person with dementia was away from the caregiver, but there were also significant reductions in behavioral problems during the evening and improved sleep immediately following ADS use.

Discussion.

ADS use lowered caregivers’ exposure to stressors and may improve behavior and sleep for people with dementia on days they have ADS. The study highlights how a within-person design can identify the effects of an intermittent intervention, such as ADS.

Keywords: Behavior problems, Caregiving, Dementia, Intervention

ADULT day service (ADS) and other types of respite programs are promising strategies for reducing the burden on family caregivers. Caregivers whose family member use ADS consistently report positive benefits for themselves, but to date, results of systematic evaluations of programs’ effectiveness have had mixed outcomes. Some studies show reductions in caregiver burden and emotional distress (Gitlin, Reever, Dennis, Mathieu, & Hauck, 2006; Zarit, Stephens, Townsend, & Greene, 1998), but other studies have found little or no impact on caregiver outcomes (Baumgarten, Lebel, Laprise, Leclerc, & Quinn, 2002; Gottlieb & Johnson, 2000; Zank & Schacke, 2002). To clarify these differences and address limitations in prior research, the present article uses a within-person design to examine how ADS use affects caregivers’ exposure to and appraisal of care-related stressors.

Evaluations of the effectiveness of ADS face three main research design challenges. First, a randomized trial is usually not feasible. People who want to use one particular type service are generally not willing to be assigned to another service or to a wait list or no-treatment control group. Furthermore, the duration of time of a control condition would need to be fairly long, thus raising ethical concerns of withholding treatment as well as leading to attrition in the sample or to a confound of treatment and control condition as caregivers seek out comparable services on their own. Several examples in the literature (e.g., Lawton, Brody, & Saperstein, 1989; Newcomer, Fox, & Harrington, 2001) underscore the difficulties associated with randomized trials of respite services.

A second issue affecting the validity of the traditional treatment-control design is caregivers are quite heterogeneous, both in terms of their own personal characteristics as well as the demands and challenges they face in their caregiving situation. A caregiver may be a husband, wife, daughter, daughter-in-law, or son to the care receiver or have some other type of relationship. Kin relationship may affect in obvious and subtle ways how caregivers perceive and respond to stressors as well as their readiness to use a variety of services (e.g., Lyons, Zarit, & Townsend, 2000; Zarit, Stephens, Townsend, Greene, & Leitsch, 1999). The variability due to factors such as the type and severity of the care receiver's problems, caregivers’ competing obligations, economic resources, and the personality of both parties in the care dyad could all affect treatment response. Indeed, the extent of variability may be greater than in other types of treatment studies because of the need to consider characteristics of both the caregiver and care receiver that could potentially affect treatment response and outcome. Under the best conditions and assuming a large sample, the heterogeneity in caregiver samples is likely to result in relatively small treatment effects, a finding that largely describes the extant literature (Gallagher-Thompson & Coon, 2007; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2006; Zarit & Femia, 2008).

The third challenge concerns the use of retrospective reports of caregiving stressors and their effects. Typical measures assess stressors and well-being over some previous time period, usually the past week or month. Participants are, in effect, asked to average their experiences over the designated time period. In doing so, they may be likely to recall more intense emotional experiences during the period (Thomas & Diener, 1990), rather than their true average experience. In the context of ADS use, caregivers may be more likely to recall the frequency and impact of stressful situations on days their relative was with them the whole day while underestimating their experiences on days when their relative attended ADS for a portion of the day. Global retrospective reports of stressors and emotions are also likely to reflect personality traits that affect the characteristic ways that people appraise and report events and emotions (Costa, Somerfield, & McCrae, 1996; Diener, 1984). Considerable evidence suggests that global reports of well-being are relatively stable and are not responsive to everyday environmental influences (Cervone, 2004; Diener, Lucas, & Scollon, 2006; Lykken & Tellegen, 1996).

ALTERNATIVE DESIGNS TO THE RANDOMIZED CONTROL TRIAL

The within-subject withdrawal design (A-B-A-B) is a classic approach in psychological research that has the potential to address these challenges in evaluating the effects of ADS and other caregiver interventions (see Barlow, Nock, & Hersen, 2009 for a comprehensive discussion). An A-B-A-B design begins with a baseline period (A) during which a targeted outcome is observed without intervention. Treatment (B) is then introduced, with continued measurement of the outcome. Next, treatment is withdrawn (A). If the outcome returns to or near its baseline level during this withdrawal period, the intervention can be considered to have a controlling effect on the outcome (Barlow et al., 2009). Treatment can then be reintroduced (B) to restore the previous benefits and provide additional evidence of the linkage between intervention and outcome.

In a within-subject design, participants serve as their own controls. A placebo or control condition does not have to be created or maintained over time nor do the practical and ethical conundrums of random assignment have to be dealt with, such as diverting people who have already made a decision to use a particular service into a control group or the futility of randomly assigning people to a service they have not chosen to use. Because participants serve as their own controls, comparisons can focus on within-person changes, rather than between-person differences in treatment response which may be confounded by personal and situational characteristics that are only partly accounted for by a control group. Additionally, within-subject designs have traditionally emphasized the use of contemporaneous assessment of specific occurrences of behavior and emotional responses, rather than global retrospective reports. This approach to measurement reduces demands on recall as well as the potential bias associated with longer recall periods (Almeida, 2005; Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003).

The present study used a within-subject withdrawal design (A-B-A-B) to study the effects of ADS use on exposure and emotional response to stressors for family caregivers of people with dementia. Research on ADS is well suited for this type of design because treatment (ADS use) is provided on some days and not others. In this study, we used a 24-hr daily diary to obtain baseline measures (A) of care-related stressors before ADS use has been initiated and then at subsequent points over a two-month period on treatment days (B) when their relative goes to ADS and on non-ADS days (A). The non-ADS days (A) represent the withdrawal phase in the design. Using this design, we proposed two related hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that caregivers’ exposure to and appraisal of care-related stressors will be lower on days they use ADS compared with non-ADS days. By examining the whole day on these occasions, we can take into account both the period of time their relative is away from the caregiver, when there would be no exposure tocare-related stressors, as well as the phases of the day when they are together. Although it seems apparent that ADS use should reduce total exposure to stressors over a 24-hr period, prior work suggests that care-related stressors may be shifted to other phases of the day (e.g., Barry, Zarit, & Rabatin, 1991; Gottlieb & Johnson, 2000). During the morning, caregivers may struggle to get their relatives ready in time to go to a day care program, whereas in the evening, they may have to deal with problems that result from the separation or transition back home. Confirming that exposure to stressors is actually reduced with ADS use is an important step akin to a manipulation check or to determining that an intervention has achieved its intended proximal effects. If ADS use provides time away, but does not actually lower stress exposure, it may be of little value. Second, we hypothesized that behavior problems will be lower over time in those periods of the day following ADS use (evening and overnight). The activities and social engagement at an ADS program may lead to reductions in behavioral problems, such as restlessness or depressive feelings, when the person comes home from day care. Thus, examination of the full 24-hr period on days when caregivers have used and not used ADS will provide information on whether and to what extent the intervention is associated with changes in the exposure to and impact of care-related stressors and if there are reductions of stressors following ADS use.

METHOD

Procedures

Recruitment of family caregivers and the individuals with dementia (IWDs) they were assisting was done with the help of the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services. Twenty-three ADS programs made referrals during the course of the study. ADS staff described the study to caregivers enrolling their relative into a program and with the caregivers’ verbal consent, forwarded names to our recruitment coordinator who then conducted a telephone interview to screen them for eligibility for the study. After eligibility was confirmed, trained interviewers conducted an in-home interview and subsequently conducted daily interviews. The interviewers were blind to the study's hypotheses, though they were aware whether daily interviews were for an ADS or non-ADS day. Caregivers reviewed and signed a consent form for their participation and also for conducting brief testing of the IWD. The IWD was also asked to give verbal consent to the testing. Procedures were approved by the Penn State University Institutional Review Board.

During the in-home interview, the interviewer explained the daily interview procedures, arranged the date of the first daily interview, and left a packet of daily diaries for the caregiver to record care-related stressors and stress appraisals. The first two daily diaries were completed before the IWD attended ADS and served as the initial baseline (A) period. Baseline days were selected when caregivers would be at home with the IWD for most of the day (not away for more than four consecutive hours). Two days were selected based on pilot data that suggested that levels of stressors were relatively stable from day to day and that two days were sufficient to obtain a reliable estimate of frequency of behavioral stressors.

Daily diaries were obtained again one month and two months following this baseline period. A two-month period was determined based on consultation with ADS programs who considered it an optimal period for IWDs to adjust and begin demonstrating benefits from the program. For each participant, ADS attendance followed a fixed schedule of days agreed upon at the outset by the caregiver and ADS program. Drawing on this information, the interviewer scheduled two daily interviews each month for days when the IWD was scheduled to attend ADS (B days) and two days when the IWD was scheduled to be at home with the caregiver (A days). A total of 1,043 (87.35%) of the scheduled calls over all occasions was completed. The main reason for omissions was difficulty scheduling on the part of either interviewer or caregiver. Order of the days was allowed to vary, depending on the attendance schedule that a particular participant followed. Interviewers called participants the morning after each diary day and obtained information for the 24-hr period (from the previous morning to the current morning). The caregiver was first asked whether the IWD attended or did not attend ADS. If ADS had been scheduled and the IWD did not attend or vice versa, the data for that day were discarded because of a concern that these days might introduce bias into the observations. For example, if the IWD stayed home from ADS because of illness, we did not reclassify the day as a control (A) day because the IWD's illness might lead to higher rates of stressors during that day than on a typical control day. Five daily interviews had to be eliminated for these reasons.

IWDs in the study attended their ADS program, on average, for three days a week. They spent an average of 6 hr (usually 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.) at the program, not counting travel time. Based on reports obtained from the ADS programs, IWDs in the study participated in five to six different activities a day. Apart from daily routines such as lunch, activities included, on average, 30 min of physical activities, 1–2 hr of social activities, and 1 hr of programming focused on cognitive stimulation (Woodhead, Zarit, Braungart, Rovine, & Femia, 2005). There was little variation in scheduled activities among the ADS programs participating in the study.

Participants

Participants were family caregivers of IWDs who were enrolling their relative into an ADS program for the first time. To be eligible, caregivers had to have primary responsibility for the IWD, live in the same household, and be able to read, write, and speak English with some fluency. In addition, the IWD had to have a physician's diagnosis of dementia. Evidence of symptoms of dementia was confirmed through in-person testing for cognitive impairment with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), caregivers’ reports of difficulties in instrumental or basic activities of daily living, and a history of worsening of memory over time.

A total of 150 caregivers who met eligibility requirements were enrolled in the study. For the present analysis, we did not include the responses of caregivers (n = 17, 11.33%) who failed to complete any daily reports beyond the initial baseline period or who did not complete daily reports on both ADS and non-ADS days (n = 12, 8%). If the caregiver missed some daily interviews, we used all available information in the analysis. The resulting sample was 121 caregivers (80.67%). Characteristics of caregivers and IWDs who were included in the study and those who were not are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were found in any social characteristics or severity of dementia. The final sample comprised primarily of spouses (35%) and adult daughters (62%) of the IWD. The sample was well educated, averaging nearly fourteen years of school. The proportion of African American participants (14%) was similar to the population of New Jersey as a whole.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Caregivers and IWDs

| Included sample (N = 121) | Excluded sample (N = 29) | t or chi-square test | |

| Caregivers | |||

| Age, M (SD) | 60.16 (12.26) | 62.79 (12.57) | −0.953 |

| Education, M (SD) | 13.83 (1.99) | 13.76 (2.56) | 0.130 |

| Income, M (SD) | 5.21 (3.07) | 5.58 (3.02) | −0.536 |

| Gender, frequency (%) | |||

| Female | 99 (81.8) | 24 (82.8) | 0.014 |

| Male | 22 (18.2) | 5 (17.2) | |

| Kin relationship, frequency (%) | |||

| Spouse | 43 (35.5) | 13 (44.8) | 1.034 |

| Child | 75 (62.0) | 15 (51.7) | |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Marital status, frequency (%) | |||

| Married | 92 (76.0) | 19 (65.5) | 1.345 |

| Not married | 29 (24.0) | 10 (34.5) | |

| Race, frequency (%) | |||

| White | 104 (86.0) | 27 (93.1) | 1.082 |

| Other | 17 (14.0) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Severity of IWDs | |||

| MMSE, M (SD) | 14.40 (6.42) | 15.14 (6.84) | −0.534 |

| ADL dependency, M (SD) | 22.60 (6.95) | 22.59 (5.99) | 0.012 |

| IADL, M (SD) | 17.49 (3.34) | 17.76 (2.79) | −0.404 |

| PADL, M (SD) | 5.12 (4.55) | 4.83 (4.12) | 0.312 |

| Behavior problems (WRB) | |||

| Frequency, M (SD) | 15.99 (9.36) | 16.21 (11.86) | −0.105 |

| Appraisal, M (SD) | 24.63 (17.08) | 22.10 (19.14) | 0.698 |

Notes: Due to missing data for the included and excluded samples n = 120 and 28 for caregiver age, 120 and 29 for caregiver education, 112 and 24 for income, and 104 and 28 for the MMSE. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; IWDs = individuals with dementia; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; PADL = personal activities of daily living; WRB = Weekly Record of Behavior.

Measures

Daily interviews.—

Daily care–related stressors were measured with the Daily Record of Behavior (DRB) (Fauth, Zarit, Femia, Hofer, & Stephens, 2006). The DRB is an expanded 44-item version of the widely used Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist (Teri et al., 1992) modified for daily use. For the present analysis, we used 21 of the 44 items. We omitted items assessing positive behaviors and daytime naps, which were not stressors for caregivers, and reality problems (e.g., not recognizing one's home), which occurred with a very low frequency. We also omitted items pertaining to memory and incontinence, which were not associated with the other behavior problems. The remaining 21 items fell into four domains: (1) resisting assistance with activities of daily living (3 items), (2) agitated and restless behavior (10 items), (3) mood (5 items), and (4) nighttime sleep disturbances (3 items).

Caregivers completed the DRB at baseline (two days prior to starting ADS), one month (two ADS days and two non-ADS days), and two months (two ADS days and two non-ADS days), for a total of ten days during the two-month observation period. Interviews were obtained on consecutive days in most instances, but in some cases, there were gaps due to the caregiver's schedule or needing to obtain a specific type of day (ADS or non-ADS). Each administration of the DRB covered a 24-hr period of time. Days were divided into four phases: (1) waking to 9 a.m., (2) 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., (3) 4 p.m. to bedtime, and (4) nighttime. The 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. phase corresponds to the time the IWD would typically attend ADS, whereas the other phases are times that caregivers would be assisting their relative. For each phase except nighttime, caregivers were asked whether each behavior had occurred during this time (yes or no), the number of times the behavior occurred, how long the behavior lasted (in minutes), and the caregiver's stressor appraisal (0 = did not occur; 5 = very upsetting). For the nighttime period, interviewers asked about sleep disturbances and an open-ended question about behavior problems throughout the night.

We constructed scores for the total duration in time for each behavior problem within each phase of the day by multiplying the number of times the behavior occurred with the average duration in minutes of each episode of the behavior. From these estimates, we created the following scores: (1) total duration in minutes of all behavior problems during each phase of the day and (2) total duration of all behavior problems for the whole day. We also computed sums for each of the four domains of behavior for each phase of the day and for the whole day. Similar total scores for caregivers’ appraisals to behavior problems were computed, as well as a mean reactivity score (appraisal/total behaviors). Alphas for the full day ranged from .58 to .79 for duration (M = 0.68) and .60 to .77 for appraisal of behavior problems (M = 0.69) across all days. Scores for each pair of days (e.g., ADS days at one month) were averaged to reduce the influence that a day with unusually high or low problems would have on the findings.

In-home interview.—

The in-home interview assessed caregivers’ and IWDs’ social and demographic characteristics, including age, education, income, kin relationship between the IWD and caregiver, marital status, race, and ethnicity.

Three measures were obtained during the in-home interview to indicate the severity of dementia. Global cognitive impairment of the IWD was assessed with the MMSE (Folstein et al., 1975). Second, caregivers provided information on the IWD's functioning on seven instrumental activities of daily living and six personal activities of daily living (Lawton & Brody, 1969). Each activity was rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (able to perform the ability by self without help) to 3 (unable to perform activity by self at any time). Scores were summed to create a single measure of ADL dependency (α = .86). The third measure of severity was a retrospective measure of behavioral, memory. and mood problems, the Weekly Record of Behavior (WRB). The WRB used the same items as the DRB. Caregivers rated how frequently each problem occurred in the past week, with scores ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (many times a day) and how upsetting they found the behavior, with ratings ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very upsetting). Internal consistencies (α) were .72 for the frequency of problems and .81 for appraisals of problems.

Analysis

Multilevel modeling (MLM) using SAS PROC MIXED (Littell, Miliken, Stroup, & Wolfinger, 1996) was employed to examine changes in the frequency of behavior problems and appraisals of behavior problems. We used a total score for duration of all behavior problems for whole days. Additional models were estimated for the four phases of the day and for each of the four behavioral domains. Similar analyses were performed with caregivers’ appraisals to behavior problems. In all models, we designated measurements collected on three occasions (baseline, one month, and two months) as the time variable and we centered time at baseline. We parameterized the baseline models as follows:

The behavior problems, BPit (either the exposure to behavior problems or caregivers’ appraisal of behavior problems) of person i at occasion t is a function of an individual-specific intercept parameter, Li (level at baseline), and individual-specific slope parameter, Sli (change over occasion), and a residual error, eit. Next we introduced type of day, that is, whether the IWD used or did not use ADS on that day. At Level 2, we controlled for the possible effects of severity of dementia using the measure of ADL disability. We considered use of the MMSE, but missing data on some IWDs (n = 17) would have reduced the sample size. We also considered whether initial levels of behavior problems (WRB) might affect changes in behavior problems over occasions or caregivers’ reactions to them. An IWD with higher levels of problems might not be responsive to behavioral cues or efforts to manage those problems, whereas someone with lower initial problems might not be able to demonstrate a decrease because of the limited range possible for improvement. For those reasons, we used the total of frequency or appraisal of behavior problems on the WRB at baseline as a covariate. We also computed a WRB × Type of Day interaction and a three-way interaction (WRB × Type of Day × Occasion of Measurement) to assess how initial severity might affect change over occasions. The three-way interaction was trimmed from models where it was not significant. All variables were centered before computing the interaction terms.

RESULTS

The means of duration and appraisal of behavior problems for the baseline, one-month, and two-month occasions for ADS and non-ADS days are shown in Table 2. At baseline, the mean total daily exposure to behavior challenges was just over 2 hr each day (M = 121.04 min). The mean exposure to behavior problems varied during the different phases of the day, with Phase 2 having the greatest exposure. After one and two months of ADS use, the mean total exposure on non-ADS days stayed approximately the same; however, exposure on ADS days went down to 75 min at one month and to 52 min at two months.

Table 2.

Means of Duration and Appraisal of Behavior Problems by Type of Day and Phase of the Day

| Type of day | Occasion | All phases |

Phase 1 (waking to 9 a.m.) |

Phase 2 (9 a.m. to 4 p.m.) |

Phase 3 (4 p.m. to bedtime) |

Phase 4 (nighttime) |

|||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Duration of behavior problems (in minutes) | |||||||||||

| Non-ADS day | 1 | 121.04 | 142.98 | 21.12 | 38.76 | 46.71 | 65.78 | 34.90 | 51.03 | 18.38 | 40.75 |

| Non-ADS day | 2 | 132.99 | 154.32 | 20.68 | 37.71 | 54.32 | 81.33 | 35.85 | 55.06 | 22.46 | 40.14 |

| Non-ADS day | 3 | 131.45 | 180.03 | 15.01 | 30.57 | 60.36 | 96.57 | 40.85 | 69.64 | 15.40 | 39.04 |

| ADS day | 2 | 75.72 | 87.15 | 17.08 | 27.08 | 2.48 | 14.36 | 39.65 | 57.23 | 16.36 | 33.29 |

| ADS day | 3 | 52.10 | 70.10 | 14.58 | 23.52 | 1.60 | 7.82 | 24.54 | 42.56 | 11.30 | 21.89 |

| Appraisal of behavior problems | |||||||||||

| Non-ADS day | 1 | 20.71 | 18.45 | 4.36 | 6.14 | 7.56 | 7.89 | 7.19 | 7.57 | 1.60 | 2.61 |

| Non-ADS day | 2 | 21.49 | 20.61 | 4.87 | 7.27 | 7.38 | 7.22 | 6.96 | 8.34 | 2.27 | 3.09 |

| Non-ADS day | 3 | 18.94 | 19.22 | 3.88 | 6.37 | 7.14 | 8.31 | 6.45 | 7.31 | 1.48 | 2.22 |

| ADS day | 2 | 14.22 | 13.09 | 4.97 | 6.04 | 0.72 | 2.78 | 6.81 | 7.64 | 1.72 | 2.10 |

| ADS day | 3 | 11.12 | 11.33 | 4.10 | 5.13 | 0.49 | 1.90 | 5.13 | 6.41 | 1.39 | 2.14 |

Note: ADS = adult day services.

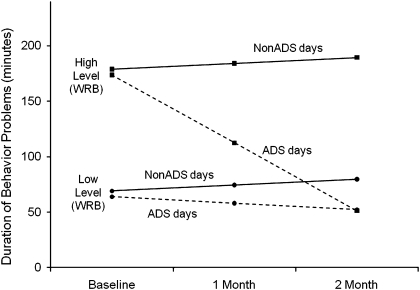

Table 3 shows the results of the multilevel models (MLM) for duration of behavior problems. The Occasion × Type of Day (ADS vs. non-ADS) interactions were significant for total exposure to stressors and for exposure during the 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. phase. The three-way Occasion × Type of Day × WRB interactions were significant for total exposure, exposure during the 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. phase, the 4 p.m. to bedtime phase, and the nighttime phase. To illustrate the interaction, we divided the sample at the mean on the WRB into groups with high (n = 59, 49%) and low initial WRB scores (n = 62, 51%). Figure 1 shows that exposure to behavior problems decreased over two months on ADS compared with non-ADS days, with the difference becoming greater for caregivers who reported high levels of behavior problems as indicated by the WRB. Much of this effect was due to reduced exposure while the IWD attended ADS, but, as noted, problems were also significantly lower on ADS days in the late afternoon to bedtime and nighttime periods.

Table 3.

Multilevel Models of Changes in Duration of Behavior Problems by Phase of the Day

| All phases |

Phase 1 (waking to 9 a.m.) |

Phase 2 (9 a.m. to 4 p.m.) |

Phase 3 (4 p.m. to bedtime) |

Phase 4 (nighttime) |

||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | 122.74*** | 12.12 | 22.25*** | 3.37 | 46.30*** | 8.71 | 34.04*** | 4.81 | 20.71*** | 3.28 |

| Occasiona | 5.26 | 7.86 | −3.25 | 1.80 | 7.20 | 7.53 | 3.38 | 3.31 | −2.45 | 1.87 |

| Type of dayb | −5.18 | 9.43 | −1.42 | 1.86 | −6.29*** | 10.48 | 3.70 | 4.38 | −2.59 | 1.70 |

| WRB | 6.93*** | 0.91 | 1.16** | 0.37 | 3.50*** | 1.44 | 2.08*** | 0.41 | 5.82*** | 1.25 |

| Interaction terms | ||||||||||

| Occasion × Type of Day | −38.15*** | 7.73 | — | −29.78*** | 8.73 | −7.24* | 3.59 | — | ||

| Occasion × WRB | — | −0.50* | 0.21 | — | — | — | ||||

| Occasion × Type of Day × WRB | −3.58*** | 0.53 | — | −2.29*** | 0.29 | −0.79** | 0.25 | −1.96** | 0.64 | |

Notes: Parameter estimates are fixed effects. Activity of daily living dependency (at baseline) was included as a control variable. ADS = adult day services; WRB = Weekly Record of Behavior.

Occasion (baseline = 0; 1 month = 1; 2 months = 2).

Type of day (Non-ADS day = 0; ADS day = 1).

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Figure 1.

Changes of duration of behavior problems in minutes over two months.

We next considered the frequency of each of the four domains of behavior problems for the baseline, one month, and two-month occasions for ADS and non-ADS days for the total day (available in a Supplementary Table in the online version of the paper). The results of the MLM appear in Table 4. There were significant three-way Occasion × Type of Day × WRB interactions for all four domains of behavior problems. The interactions indicated that there was less exposure to each type of behavior problems on ADS compared with non-ADS days over the two-month time period, and the difference was greater for IWDs who had higher baseline levels of behavior problems.

Table 4.

Multilevel Models of Duration of Behavior Problems by Behavioral Domain

| ADL (all phases) |

Mood (all phases) |

Agitated (all phases) |

Sleep (all phases) |

|||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | 15.26*** | 3.11 | 5.77** | 1.82 | 81.28*** | 9.54 | 20.71*** | 3.28 |

| Occasiona | −0.40 | 2.47 | 0.80 | 1.25 | 6.86 | 6.31 | −2.45 | 1.87 |

| Type of dayb | 0.41 | 2.36 | 0.58 | 1.58 | −4.54 | 7.82 | −2.59 | 1.70 |

| WRB | 5.16*** | 1.04 | 1.97*** | 0.30 | 7.72*** | 0.99 | 5.82*** | 1.25 |

| Interaction terms | ||||||||

| Occasion × Type of Day | −3.86* | 1.94 | −3.01* | 1.29 | −30.05*** | 6.41 | — | |

| Occasion × Type of Day × WRB | −1.76* | 0.71 | −1.70** | 0.25 | −3.73*** | 0.61 | −1.96** | 0.64 |

Notes: Parameter estimates are fixed effects. ADL dependency (at baseline) was included as a control variable. ADL = activities of daily living; ADS = adult day services; WRB = Weekly Record of Behavior.

Occasion (baseline = 0; 1 month = 1; 2 months = 2).

Type of day (Non-ADS day = 0; ADS day = 1).

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

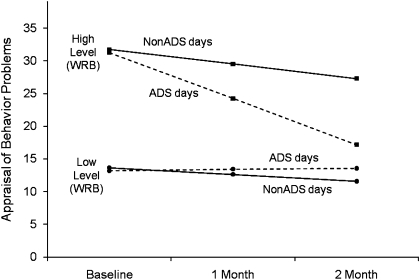

Results for appraisals of behavior problems are shown in Table 5. There were significant two-way Occasion × Type of Day interactions and significant three-way interactions for the whole day and for the 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. phase. As illustrated in Figure 2, the three-way interaction suggests that caregivers’ total appraisal of stress was lower on ADS days, and the amount of decrease was greater when initial levels of behavior problems were higher. This effect was due primarily to decreased exposure to problems during the 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. phase.

Table 5.

Multilevel Models of Changes in Appraisal of Behavior Problems

| All phases |

Phase 1 (waking to 9 a.m.) |

Phase 2 (9 a.m. to 4 p.m.) |

Phase 3 (4 p.m. to bedtime) |

Phase 4 (nighttime) |

||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | 21.06** | 1.43 | 4.52** | 0.52 | 7.50** | 0.65 | 7.36** | 0.63 | 1.87** | 0.21 |

| Occasiona | −0.67 | 0.86 | −0.11 | 0.29 | −0.25 | 0.41 | −0.49 | 0.35 | −0.04 | 0.13 |

| Type of dayb | −0.96 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 0.35 | −0.95 | 0.54 | −0.32 | 0.36 | −0.20 | 0.12 |

| WRB | 0.55** | 0.06 | 0.16** | 0.03 | 0.22** | 0.02 | 0.18** | 0.03 | 0.33** | 0.05 |

| Interaction terms | ||||||||||

| Occasion × Type of Day | −3.76** | 0.91 | — | −3.36** | 0.44 | — | — | |||

| Occasion × WRB | — | −0.03* | 0.02 | — | — | — | ||||

| Type of Day × WRB | — | — | — | — | −0.15** | 0.03 | ||||

| Occasion × Type of Day × WRB | −0.17** | 0.03 | — | −0.14** | 0.02 | — | — | |||

Notes: Parameter estimates are fixed effects. Activity of daily living dependency (at baseline) was included as a control variable. ADS = adult day services; WRB = Weekly Record of Behavior.

Occasion (baseline = 0; 1 month = 1; 2 months = 2).

Type of day (Non-ADS day = 0; ADS day = 1).

*p < .05; **p < .001.

Figure 2.

Changes in total appraisal of behavior problems over two months.

Caregivers’ reactivity (i.e., average upset per behavior problem) decreased significantly across all days over the two-month period (B = −0.10, p < .05). There was a significant Occasion × WRB interaction (B = 0.10, p < .05), indicating that caregivers with higher initial stress appraisals on the WRB increased more over time. No three-way interactions were significant (available in Supplementary Tables in the online version of the paper).

DISCUSSION

Using an A-B-A-B within-person design that involved a multilevel examination of behavior problems reported on ADS versus non-ADS days, we found evidence that ADS use over a two-month period resulted in reduced stress exposure and stress appraisals as reported by family caregivers of people with dementia, and behavioral problems were lower in the evenings and nights following ADS use.

The findings of reduced stress exposure can be explained in part by the fact that the caregiver and IWD were apart for a portion of the day when the IWD attended ADS and thus caregivers had little or no exposure to care-related stressors during that time. Although an obvious finding, the result is noteworthy because it provides, in effect, a manipulation check that confirms that ADS use provides time away for the caregiver and meaningful relief from care-related stressors. Though time away and respite should logically be linked, it has often been argued that ADS and other types of respite just shift stressors from one portion of the day to another (e.g., Barry et al., 1991) or in other ways fail to reduce the challenges faced by caregivers (e.g., Gottlieb & Johnson, 2000). We have shown that ADS not only allows time away for the caregiver but also achieves its immediate goal of providing respite by lowering stress exposure. In real time, this difference in exposure amounted to over 1 hr a day by the second month of ADS use. Stress appraisals were also lower on ADS days due to the reduction in exposure. By providing time away and lowering stress exposure, ADS is an effective way of delivering respite to caregivers of people with dementia.

Our results also confirm the hypothesis that ADS use lowers behavioral problems immediately following ADS use from the time the IWD comes home through the overnight period. One explanation is that the activities at ADS, which provide physical, cognitive, and social stimulation, lead to a reduction in problematic behaviors after IWDs come home. This explanation is consistent with the premise that behavioral and emotional problems in dementia result in part from a lack of activity (Femia, Zarit, Stephens, & Greene, 2007). Prior studies have found that increasing activities can lead to improved behavior and sleep in IWDs (McCurry, Gibbons, Logsdon, Vitiello, & Teri, 2005; Richards, Beck, O’Sullivan, & Shue, 2005; Teri, Logsdon, Uomoto, & McCurry, 1997). We also note that the finding that IWDs with fewer initial behavior problems received less benefit from ADS use probably was due to a floor effect. Perhaps about one quarter of IWDs had very few behavior problems across all days of the study and had little variation across type of day.

The findings demonstrate the value of a within-person design that utilizes daily short-term recall of behavior problems around the immediate administration of an intervention (ADS). Previous studies using between-person designs have shown mixed effects of ADS on a variety of caregiver outcomes (e.g., Baumgarten et al., 2002; Gitlin et al., 2006; Gottlieb & Johnson, 2000; Zank & Schacke, 2002; Zarit et al., 1998). Both the use of retrospective reports which average caregivers’ experience across ADS and non-ADS days as well as the heterogeneity within caregiving samples may have contributed to these varied outcomes. A within-person designs allows for people to serve as their own controls across multiple baseline and intervention periods (Barlow et al., 2009), and daily use of measures facilitates identification of immediate outcomes of an intervention. The reduction of exposure to care-related stressors and in stress appraisals identified in this study may be considered beneficial for their own sake but may also have longer term implications for health and well-being. As a result of reduced stress exposure, caregivers who use respite in a timely manner or who receive sufficient respite may have fewer of the negative consequences associated with chronic exposure to stressors.

The potential benefits of reduction of stressor exposure with ADS use could be offset if caregivers engage in other stressful activities and interactions when their relative is at ADS. Gottlieb and Johnson (2000) have noted that caregivers do not use the time that the IWD is in day care to rest or engage in leisure activities, rather, caregivers are often catching up on household chores and errands, or they are employed. The current study did not obtain information about time use or non–care-related stressors; however, caregivers did report subjectively that they were able to relax when their relative was at ADS, and working caregivers indicated only small to moderate problems balancing work and caregiving.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, the sample was limited to caregivers who lived with the IWD. The effects of ADS use on daily stressors of other caregivers would likely differ. The sample also had higher levels of education and income than the population of New Jersey as a whole. Although the proportion of African Americans was similar to the state's population, we were not able to recruit from the growing Hispanic and Asian populations in New Jersey. Second, daily assessments did not include measures of caregivers’ emotional distress or health symptoms, both of which could be important information for understanding the potential effects of ADS use and other types of respite. The most obvious impact of respite is likely to be on well-being during and after ADS use. Third, the procedure of averaging type of day at each time period provided a conservative estimate of differences in stressors between ADS and non-ADS days but also necessarily does not present important variability that may occur within type of days for some caregivers. Fourth, although interviewers were blinded to the study's hypotheses, they were of necessity aware of whether a daily interview occurred on an ADS or non-ADS day, and so we cannot rule out possible bias in the interviews. Fifth, we were also not able to test the effects of order of days (whether an ADS day followed a non-ADS or another ADS day) or lagged or cumulative effects. The study sample was too small, and the patterns of ADS use were too varied to perform a test for these effects. Finally, sample attrition was relatively small during the two-month period of observation. We did not, however, include later follow-up periods due to more extensive attrition. By three months, only 63% of the original sample was still enrolled in ADS and participating in the study. Attrition was due to institutionalization (10%), death of the IWD (4%), refusal (17%), and lost contact (3%). Thus, for at least some caregivers, the period of benefits experienced with ADS use was closely associated with deterioration or death of the IWD. Additionally, the study protocol placed heavy response demands on caregivers who were already managing complex schedules.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that ADS use benefits both family caregivers and IWDs. ADS programs can build on these findings by increasing their focus and involvement on family caregivers (e.g., Gitlin et al., 2006) and by exploring in more systematic ways the therapeutic potential of the activities and socialization opportunities they offer. Engagement in meaningful activities has considerable potential to improve behavior and sleep without the side effects associated with pharmacological treatments. By reducing behavior problems and improving sleep in people with dementia, even in small amounts, ADS and other activity-based programs may be of considerable value to caregivers and may help them keep their relative at home for a longer period of time.

FUNDING

This research was supported by a grant funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, R01 MH59027, “Reducing Behavior Problems in Dementia: Day Care Use.”

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material can be found at: http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/

References

- Almeida DM. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Nock MK, Hersen M. Single case experimental designs: Strategies for studying behavior change. 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn & Bacon; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barry GL, Zarit SH, Rabatin VX. Caregiver activity on respite and nonrespite days: A comparison of two service approaches. The Gerontologist. 1991;31:830–835. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.6.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten M, Lebel P, Laprise H, Leclerc C, Quinn C. Adult day care for the frail elderly: Outcomes, satisfaction, and cost. Journal of Aging and Health. 2002;14:237–259. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervone D. The architecture of personality. Psychological Review. 2004;111:183–204. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr., Somerfield MR, McCrae RR. Personality and coping: A reconceptualization. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications. New York, NY: Wiley; 1996. pp. 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:542–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Lucas RE, Scollon CN. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist. 2006;61:305–314. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth ER, Zarit SH, Femia EE, Hofer SM, Stephens MAP. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and caregivers’ stress appraisals: Intraindividual stability and change over short term observations. Aging and Mental Health. 2006;10:563–573. doi: 10.1080/13607860600638107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Femia EE, Zarit SH, Stephens MAP, Greene R. Impact of adult day services on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:775–788. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW. Evidence-based psychological treatments for distress in family caregivers of older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:37–51. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Reever K, Dennis MP, Mathieu E, Hauck WW. Enhancing quality of life of families who use adult day services: Short- and long-term effects of the Adult Day Services Plus Program. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:630–639. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb BH, Johnson J. Respite programs for caregivers of persons with dementia: A review with practice implications. Aging and Mental Health. 2000;4:119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM, Saperstein AR. A controlled study of respite services for caregivers of Alzheimer's patients. The Gerontologist. 1989;29:8–16. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Miliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS systems for mixed models. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lykken D, Tellegen A. Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science. 1996;7:186–189. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Zarit SH, Townsend AL. Families and formal service usage: Stability and change in patterns of interface. Aging and Mental Health. 2000;4:234–243. [Google Scholar]

- McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Logsdon RG, Vitiello MV, Teri L. Nighttime insomnia treatment and education for Alzheimer's disease: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2005;53:793–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer RJ, Fox PJ, Harrington CA. Health and long-term care for people with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias: Policy research issues. Aging and Mental Health. 2001;5:S124–S137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: Which interventions work and how large are their effects? International Psychogeriatrics. 2006;18:577–595. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards KC, Beck C, O’Sullivan PS, Shue VM. Effects of individualized social activity on sleep in nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:1510–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, McCurry SM. Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: A controlled clinical trial. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52:159–166. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.4.p159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, Uomoto J, Zarit SH, Vitaliano PP. Assessment of behavior problems in dementia: The Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:622–631. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DL, Diener E. Memory accuracy in the recall of emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead EL, Zarit SH, Braungart ER, Rovine MR, Femia EE. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: The effects of physical activity at adult day service centers. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2005;20:171–179. doi: 10.1177/153331750502000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zank S, Schacke C. Evaluation of geriatric day care units: Effects on patients and caregivers. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:348–357. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.p348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Femia EE. A future for family care and dementia intervention research? Challenges and strategies. Aging and Mental Health. 2008;12:5–13. doi: 10.1080/13607860701616317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Stephens MAP, Townsend A, Greene R. Stress reduction for family caregivers: Effects of adult day care use. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Science. 1998;53:267–277. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.5.s267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Stephens MAP, Townsend A, Greene R, Leitsch SA. Patterns of adult day service use by family caregivers: A comparison of brief versus sustained use. Family Relations. 1999;48:355–361. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.