Abstract

Purpose

A prospective evaluation of fifty patients with faecal soiling but normal sphincter function treated by a conservative treatment algorithm.

Patients and methods

Between January 2010 and January 2011, 50 consecutive patients of two different clinical centres, with faecal soiling and normal anorectal function as assessed by endoanal ultrasound, MRI and anal manometry, were eligible for the purpose of this study. All patients started the therapy by psyllium (PS) and a fibre-rich diet daily after 2 months followed by rectal irrigation (RI) in case of incomplete response and after 4 months by 4 g colestyramine (CO), respectively. The patients completed the Vaizey incontinence score and a 2-week diary card. All tests were performed repeated after 2, 4 and 8 months, respectively.

Results

The study group consisted of 41 men and 9 women and a mean age of 38 years (21–70). The soiling complaints resolved completely in 37 (79%) patients. After treatment with PS, RI and CO, 12 (24%) patients, 24 (73%) patients and 1 (79%) patient, respectively, resolved completely of faecal soiling. Average weekly soiling frequency, the amount of patients wearing pads daily and the Vaizey incontinence score diminished significantly after treatment with psyllium and after treatment with rectal irrigation (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Conservative treatment focussed on complete evacuation or clearing the anorectal canal is effective in the treatment of patients with faecal soiling.

Keywords: Faecal Incontinence, Soiling, Rectal irrigation, Psyllium, Diet

Introduction

Patients with faecal soiling suffer from anal dermatitis and itching mostly after defecation. Faecal soiling is caused by insufficient clearing of the anal canal after normal defecation, and the anorectal manometry is usually within the normal range [1]. Faecal soiling occurs when sticky faeces stays behind in the anorectal canal and gives a local reaction at the anodermal skin which results in itching, dermatitis and loss of small amounts of brown fluid. The anorectal canal is sometimes anatomically disturbed, but many patients with faecal soiling do not have an anal defect. The anatomical disturbance is seen in patients with haemorrhoids, anal fissures tumours, fistulas, etc. or in patients who had anal surgery for these conditions resulting in scar tissue or keyhole defects. About 30 per cent of the patients surgically treated for perianal fistulas suffer from soiling [2–7]. Terms like passive incontinence and soiling are used mixed up for patients who suffer from anal leakage.

There is no standardised adequate therapy for faecal soiling. Most of the prescribed therapies consist of symptomatic conservative treatment formerly used for passive faecal incontinence. Symptomatic treatment has focussed on the perianal dermatitis by application of dermatological creams, by providing information regarding adequate anal hygiene, wearing pads or bile acid binders. In addition, fibre, including psyllium or bran, is suggested for the treatment of soiling to enhance evacuation of stools [8]. Evacuation of faeces by enemas of rectal irrigation after defecation is described in studies for soiling and retentive encopresis in children [9, 10]. Gosselink et al. described retrograde colonic irrigation in patients with bowel disorders and faecal incontinence and soiling [11].

In this study, we prospectively investigated the effectiveness of a conservative treatment algorithm for faecal soiling.

Patients and methods

All consecutive patients with faecal soiling were included in this study. All patients underwent physical examination to exclude other abnormalities like rectum tumours, external rectal prolapse or radiation effects. All patients underwent endoanal ultrasound to assess lesions or abnormalities of the anal sphincter. In case of complaints of prolapse, patients underwent a dynamic MRI scan to exclude internal prolapse, rectoceles or enteroceles. Patients with true incontinence for liquids were not included. For inclusion and exclusion criteria, see Table 1. Patients with haemorrhoids grade III without pain were included in case of soiling.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| Soiling: |

| Itching and |

| Fluid loss and/or |

| Perianal dermatitis |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Associated external sphincter defect |

| Haemorrhoids grade III with pain |

| Haemorrhoids grade IV |

| Faecal incontinence |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Rectal prolapse |

| Enterocele |

| Rectocele >1 cm |

| Low anterior resection |

| Acute inflammation, infection, malignancy or post-radiation |

| Age younger than 18 |

| Psychiatric diseases |

All patients completed a 2-week diary card with details of their usual bowel actions and soiling episodes and the Vaizey incontinence score. In our hospital, the Vaizey incontinence score is used because in this score soiling is an important variable [1].

After consulting members of the local ethical committee, no approval was needed because no new (experimental) treatments were offered to the patients. Written informed consent was obtained.

Intention to treat

In this study, the results of all patients that were included to undergo this procedure were analysed. In case of severe perianal dermatitis, the patient was treated by zinc oxide 10% in ketaconazole ointment for 2 weeks. Patients with grade III haemorrhoids not responding to this conservative treatment algorithm were treated by rubber band ligation in one or more sessions.

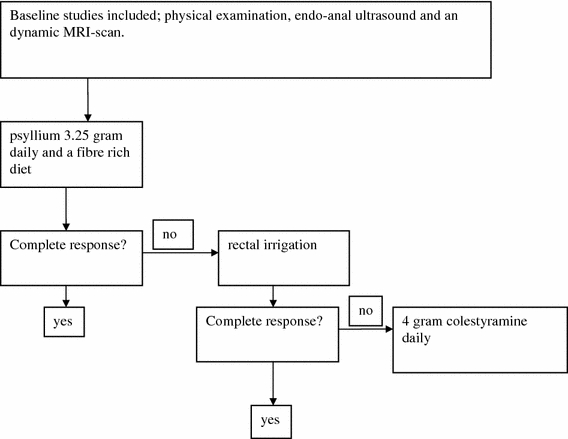

Conservative treatment algorithm (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Treatment algorithm for patients with faecal soiling

All patients were instructed how to achieve adequate anal hygiene. They were advised not to use perfumed paper or wet napkins because of potential local allergic reactions. The primary focus of the treatment algorithm was to completely evacuate stool from the anorectal canal.

First-line therapy

All patients started with psyllium 3.25 g daily and a fibre-rich diet. Psyllium binds water and enhances evacuation of stools by bulking and softening the consistency of faeces especially in patients with IBS type C (constipation) and type M (mixed diarrhoea and constipation). After 2 months, outcome and score lists were evaluated.

Second-line therapy

After 2 months, evacuation of faeces was facilitated by rectal irrigation in patients with persisting soiling complaints despite first-line therapy. The nurse practitioner (enterostomal therapist) informed patients regarding the use of bottles (REPROP®) that can contain 500 ml tap water and trained the patients at the outdoor clinic how to use it. For daytime soiling and soiling after stools, the irrigation should be done after defecation and for night-time soiling, before sleeping. The first 3 weeks, the nurse practitioner called the patients at regular intervals by phone for extra support. If necessary, the patient came back for additional consultation at the outpatient clinic. After 2 months, outcome and score lists were evaluated.

Third-line therapy

In case of persistent soiling, 4 g of colestyramine daily was added in patients without haemorrhoids grade III. Colestyramine is a resin binding bile acids, which can give skin reactions in the anodermal region when present in the stool. This may be suspected in patients with short bowel or a disrupted enterohepatic cycle of bile acids. Because prolapsing haemorrhoids can cause faecal soiling, rubber band ligation was offered to patients with haemorrhoids grade III. After 4 months, outcome and score lists were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

At baseline and at 2, 4 and 8 months, outcome was statistically analysed with the Student t test (or Wilcoxon test as appropriate) for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables (or Fisher exact test as appropriate). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Between January 2010 and January 2010, fifty patients with a median age of 38 years (range 21–70) with faecal soiling were included. The patient characteristics are described in Table 2. The soiling complaints resolved completely in 41 (79%) patients. All 50 patients underwent treatment with psyllium 3.25 g daily and a fibre-rich diet. This resolved the complaints of soiling completely in 12 patients (24%). Of the 38 patients in which soiling complaints had not been completely resolved, 37 underwent treatment with rectal irrigation. Complaints resolved completely in 24 (65%) of them and twenty of those patients stopped psyllium treatment. Eleven patients underwent treatment with 4 g colestyramine daily. In only one patient, complaints disappeared completely (9%). Eight patients (16%) had soiling complaints and haemorrhoids grade III. Four (50%) of them were completely cured after treatment with psyllium 3.25 g daily and a fibre rich. None of the remaining four patients exhibited benefit after rectal irrigation but the complaints resolved after rubber band ligation in two sessions.

Table 2.

Patients characteristics and outcome

| N = 50 | |

|---|---|

| Age | 38 (21–70) |

| Sex m:f | 41:9 |

| Patient history | |

| Anal surgery | 18 |

| Birth trauma | 8 |

| IBS type C (constipation) | 8 |

| IBS type M | 2 |

| Haemorrhoids grade III | 8 |

| Severe perianal dermatitis | 11 |

| Defects of the internal anal sphincter | 15 (30%) |

| Degeneration of the internal anal sphincter | 19 (38%) |

Average weekly soiling frequency, the amount of patients wearing pads daily and the Vaizey incontinence score diminished significantly after treatment with psyllium and after treatment with rectal irrigation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patients outcome

| N = 50 | Psyllium 3.25 g daily and a fibre-rich diet | Rectal irrigation (N = 37) | 4 gram colestyramine daily (N = 11) | N = 47 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | At 2 months | At 4 months | At 8 months | ||

| Lost in follow-up | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Complete response | 12 (24%) | 24 (73%) | 1 (79%) | 37 (79%) | |

| Average weekly soiling frequency | 6.8 (5–7) | 3.9 (0–5)* | 1.1 (0–4)* | 1.1 (0–4) | |

| Patients wearing pads daily | 35 (70%) | 33 (66%)* | 6 (12%)* | 6 (12%) | |

| The mean Vaizey incontinence score | 3.9 (0–8) | 3.2 (0–6)* | 1.0 (0–3)* | 1.0 (0–4) | |

| Patients with a lesion of the internal sphincter | 15 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 11 (73%) |

| Patients without a lesion of the internal sphincter | 35 | 8 | 17 | 1 | 26 (74%) |

* P < 0.001

Defects of the internal anal sphincter were observed in 15 (30%) patients. Degeneration of the internal anal sphincter (mean depth <2 mm) was noted in 19 (38%) patients. None of the patients with a defect or degeneration of the internal sphincter were incontinent for liquid stools. No significant differences in outcome were detected between patients with or without a defect of the internal sphincter (Table 3).

Discussion

The prevalence of soiling is unknown, but up to 19.6 per cent of the population is incontinent for flatus liquid or solid stools [12–16]. True prevalence of faecal incontinence and soiling is hard to establish because of underreporting of symptoms by patients, difference in data collection and different standardised scoring scales [17]. Soiling is only mentioned in papers dealing with anorectal diseases but never discussed on its own merit. In our opinion, soiling is caused by insufficient evacuation of faeces from the anorectal canal after normal defecation for several reasons. Important causes may be constipation, obstructed defecation or scar lesions. There is a plausible explanation for soiling in patients who have only a partial defect of the anal internal sphincter or a scar lesion (keyhole defect) after anal surgery or trauma. This scar lesion compromises complete evacuation of the (sticky) faeces. However, not every person suffering from insufficient clearing or evacuation of faeces from the anal canal with or without a scar lesion suffers from soiling. The composition of the stools and its flora and the sensitivity of the patient may explain why the one patients gets soiling whereas the other does not. This area is largely unexplored.

Vascular filling in the anal cushions has been found to contribute 15–20% of the resting anal canal pressure [18] and the anal cushions act as a “compliant and comfortable plug” at the anal margin [19]. The function and interaction between the anal cushions and the internal sphincter in the pathogenesis of faecal soiling is still not clear. In a previous study [1], no difference in resting and squeeze pressures of the anal canal was found before and after treatment in the patients that responded well to treatment with bulking agents [1]. Dysfunction of the anal sphincter is not the cause of anal soiling. Other authors found on the basis of anal manometric studies that the mechanisms of faecal soiling and faecal incontinence are different and that dysfunction of the anal sphincter was not an objective explanation for soiling [8, 20].

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and constipation are associated with faecal soiling. Drossman et al. found that patients with faecal soiling that consulted their physicians were more likely men [21]. Prolapsing haemorrhoids is another well-known cause of pruritus and faecal soiling. Murie et al. showed that haemorrhoidectomy and rubber band ligation reduce symptoms like pruritus and faecal soiling [22].

Antegrade or retrograde colonic irrigation and rectal irrigation have been widely used for functional bowel disorders and soiling [10, 11, 23]. The water irrigates the remaining faeces in the rectum after stool. The present study shows that irrigation of the anal canal in patients with faecal soiling is an effective and simple treatment modality and is more effective than psyllium and fibre-rich diet. But we still recommend this treatment algorithm because of the compliance of the patients. The patients in our study were referred to our clinic by general practitioners. Most of the patients in this study had since long suffered from severe soiling. We assume that most of these patients can be cured by instruction how to maintain adequate anal hygiene and/or by the use of psyllium. Rectal irrigation is a good second option but the long-term therapeutic benefit depends on the severity of soiling complaints on the one hand and the therapeutic compliance on the other hand. In this study, the therapeutic effect of colestyramine after failure of psyllium and rectal irrigation is poor. Colestyramine treatment may be restricted to the rare patient with bile acid malabsorption. The patients not responding to psyllium, rectal irrigation and colestyramine are unfortunately dependent on symptomatic therapies.

Conclusions

Conservative treatment focussed on complete evacuation or clearing the anorectal canal is effective in the treatment of patients with faecal soiling.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.van der Hagen SJ, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. PTQ Implants in the treatment of faecal soiling. Br J Surg. 2007;94:222–223. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmerman DD, Briel JW, Gosselink MP, Schouten WR. Anocutaneous advancement flap repair of transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1474–1480. doi: 10.1007/BF02234601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Tets WF, Kuijpers JH. Seton treatment of perianal fistula with high anal or rectal opening. Br J Surg. 1995;82:895–897. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schouten WR, Zimmerman DD, Briel JW (1999) Transanal advancement flap repair of transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1419–1422; (discussion 1422–1423) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Athanasiadis S, Nafe M, Kohler A. Transanal rectal advancement flap versus mucosa flap with internal suture in management of complicated fistulas of the anorectum. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1995;380:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seow-Choen F, Nicholls RJ. Anal fistula. Br J Surg. 1992;79:197–205. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong WD, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD. Anal fistula surgery. Factors associated with recurrence and incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:723–729. doi: 10.1007/BF02054434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann BA, Timmcke AE, Gathright JB, Jr, Hicks TC, Opelka FG, Beck DE. Fecal seepage and soiling: a problem of rectal sensation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:746–748. doi: 10.1007/BF02048034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stark LJ, Owens-Stively J, Spirito A, Lewis A, Guevremont D. Group behavioral treatment of retentive encopresis. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990;15:659–671. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz C, Drongowski RA, Coran AG. Long-term management of chronic constipation in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:976–978. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(87)80605-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosselink MP, Darby M, Zimmerman DD, et al. Long-term follow-up of retrograde colonic irrigation for defaecation disturbances. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:65–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baeten CG, Uludag O. Second-line treatment for faecal incontinence. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2002;236:72–75. doi: 10.1080/003655202320621490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parks AG (1975) Royal Society of Medicine, Section of Proctology; meeting 27 November 1974. President’s Address. Anorectal incontinence. Proc R Soc Med 68:681–690 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Nelson R, Norton N, Cautley E, Furner S. Community-based prevalence of anal incontinence. JAMA. 1995;274:559–561. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.7.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giebel GD, Lefering R, Troidl H, Blöchl H. Prevalence of fecal incontinence: what can be expected? Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s003840050138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry S, Shaw C, McGrother C, Leicestershire MRC, Incontinence Study Team et al. Prevalence of faecal incontinence in adults aged 40 years or more living in the community. Gut. 2002;50:480–484. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madoff RD, Parker SC, Varma MG, Lowry AC. Faecal incontinence in adults. Lancet. 2004;364:621–632. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16856-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lestar B, Penninckx F, Kerremans R. The composition of anal basal pressure. An in vivo and in vitro study in man. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:118–122. doi: 10.1007/BF01646870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loder PB, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Phillips RK. Haemorrhoids: pathology, pathophysiology and aetiology. Br J Surg. 1994;81:946–954. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felt-Bersma RJ, Janssen JJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Hoitsma HF, Meuwissen SG. Soiling: anorectal function and results of treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:37–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01648548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drossman DA, Sandler RS, Broom CM, McKee DC. Urgency and fecal soiling in people with bowel dysfunction. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:1221–1225. doi: 10.1007/BF01296523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murie JA, Sim AJ, Mackenzie I. The importance of pain, pruritus and soiling as symptoms of haemorrhoids and their response to haemorrhoidectomy or rubber band ligation. Br J Surg. 1981;68:247–249. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800680409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tod AM, Stringer E, Levery C, Dean J, Brown J. Rectal irrigation in the management of functional bowel disorders: a review. Br J Nurs. 2007;16:858–864. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2007.16.14.24323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]