Abstract

The Longitudinal Epidemiologic Study to Gain Insight into HIV/AIDS in Children and Youth (LEGACY) study is a prospective, multisite, longitudinal cohort of U.S. HIV-infected youth. This analysis was limited to perinatally HIV-infected youth (n=197), 13 years and older, with selected variables completely abstracted from HIV diagnosis through 2006. We evaluated relationships between ever having one or more nonsubstance related medically documented psychiatric diagnoses and three risky health behaviors (substance abuse, preadult sexual activity, and treatment adherence problems) recorded between 2001 and 2006. Logistic regression was used for all binary outcomes and participant age was included as a covariate when possible. All 197 participants included in the analysis were prescribed antiretroviral therapy during the study period; 110 (56%) were female, 100 (51%) were black non-Hispanic, and 86 (44%) were Hispanic; mean age at the last visit was 16.8 years, ranging from 13 to 24 years. One hundred forty-six (74%) participants had a history of at least one risky health behavior. There were 108 (55%) participants with at least one medically documented psychiatric diagnosis, 17 (9%) with at least one record of substance abuse, 12 (6%) with documented preadult sexual activity, and 142 (72%) participants with reported adherence problems. In the final model, a history of at least one psychiatric diagnosis was associated with having at least one of the three risky behaviors (odds ratio [OR]=2.33, p=0.015). There is a need for a continued close partnership between HIV specialty care providers and mental health services treating perinatally HIV-infected youth with an added focus on improving treatment adherence.

Introduction

Perinatally HIV-infected youth face multiple mental health risks, some of which are unique to their perinatal mode of HIV transmission. In utero exposure of the developing brain to maternal HIV infection and related immune dysregulation, followed by their own life-long HIV infection and systemic inflammation likely create vulnerability to develop unfavorable neurodevelopmental outcomes.1 This biologic vulnerability may be further aggravated not only by nonspecific factors often occurring in HIV-affected families, which are reflected in reported high rates of anxiety and depression symptoms in HIV-uninfected children living with HIV-infected parents,2 but also by psychosocial factors unique to perinatally HIV-infected youth, as evidenced in reports of behavioral complications of HIV diagnostic disclosure, especially if the disclosure was not conducted in a timely and developmentally appropriate manner.3–5 High rates of psychiatric disorders including mood, anxiety, attention deficit, and learning disorders, below-average neurodevelopmental scores as well as frank encephalopathy have been reported in this population.1,6–11 Since all psychiatric disorders may potentially affect decision making and behavior, perinatally HIV-infected youth with psychiatric disorders might be at increased risk for engaging in risky health behaviors and/or having difficulty managing their HIV infection.

Psychiatric disorders in youth frequently occur in addition to risky health behaviors such as preadult sexual activity or substance abuse.12–14 In HIV-infected youth, these behaviors may pose a public health risk by increasing the likelihood of further transmission of the virus either directly through sexual activity or intravenous drug use or indirectly through substance abuse that may facilitate unsafe sexual behavior. Psychiatric comorbidities have also been associated with impaired treatment adherence in children and adolescents who suffer from chronic medical conditions15 causing concerns that psychiatric disorders might interfere with treatment adherence in HIV-infected youth.6 Poor adherence often leads to viral replication and drug resistance, limits future treatment options,6 and increases transmission risk to future sexual partners. One recent study16 reported that adherence problems were not significantly predictive of psychiatric disorders in a U.S. cohort of perinatally HIV-infected youth, but did not examine the converse hypothesis of whether psychiatric disorders were predictive of adherence problems. More recently this converse hypothesis was examined9 and perinatally HIV-infected youth with behavioral impairment were found to have significantly increased odds of nonadherence. However, the majority of participants in that study were between 6 and 12 years old—an age range when most perinatally infected youth are typically not yet in charge of taking their medication. Neither of these two studies9,16 examined sexual activity and substance abuse in relation to psychiatric history, nor did they include history of encephalopathy among the psychiatric disorders. Thus, to our knowledge, the question of relationship of psychiatric disorders, including encephalopathy (HIV-related or other), to treatment adherence problems, preadult sexual activity or substance abuse (henceforth categorized as risky health behaviors) among perinatally HIV-infected youth, 13 years of age and older, remains unanswered.

As the cohort of perinatally HIV-infected children in the United States ages into adolescence and early adulthood, and transitions into adult clinical care settings, the answer to this question becomes increasingly important as there may be direct implications for long-term clinical management and public health. Additionally, the answer may help inform funding agencies and policy planners.

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between medically documented psychiatric diagnoses and risky health behaviors in a cohort of youth with perinatally acquired HIV infection. We hypothesized that a history of at least one psychiatric diagnosis would be associated with a history of one or more of the three risky health behaviors.

Methods

The Longitudinal Epidemiologic Study to Gain Insight into HIV/AIDS in Children and Youth (LEGACY) study is a Centers for Disease Control and Infection (CDC)-funded, observational, prospective cohort study of HIV-infected children and adolescents enrolled between birth and 24 years of age from 22 HIV specialty clinics across the United States. This study population was selected using a three-stage probability proportional to size sampling method to encourage a broad selection of HIV-infected infants, children and adolescents receiving care in 22 geographically diverse small, intermediate, and large-sized facilities. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the CDC and the IRBs of all local study sites. A consolidated 301(d) Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained for LEGACY to provide an added level of strict privacy protection for participants. Between November 2005 and June 2007, at least 80% of eligible HIV-infected youth presenting for care at LEGACY clinic sites were offered enrollment. Participation was voluntary. Written informed assent and consent was obtained from minors and parents, as appropriate. The medical records of participants were reviewed and abstracted by a trained data abstractor. The data abstraction instrument was internet based, using Oracle Clinical software customized by Westat Inc., Rockville, Maryland. All abstractors received detailed training provided by the co-project officer/study coordinator and project officer, both with extensive previous data abstraction experience. Ongoing training throughout the study was provided at regular project meetings and abstractor training sessions as well as during abstractor conference calls. Most abstractors had medical backgrounds including physicians (foreign medical graduates), registered nurses, social workers, a dietitian, graduate students public health, medical records librarian, and others. The abstractors were not fully blinded to the study hypotheses, since they were included in most project meetings including the start-up meetings where the protocol was presented. As this was an observational study, they were instructed not to interpret but rather to abstract what was in the chart. Selected variables were abstracted from birth or HIV diagnosis, whichever occurred first, with more complete data abstraction from 2001 to 2006. Data collected included demographics (age, race, ethnicity, gender, educational level); mode of HIV infection (perinatal, breastfeeding, heterosexual activity, homosexual activity, sexual abuse, blood transfusion, and injection drug use [IDU]); clinical diagnoses; antiretroviral (ARV) and non-ARV medications; vaccines; laboratory test results, including CD4+ T-lymphocyte (CD4) cell counts, plasma HIV-RNA viral loads, HIV genotype and phenotype drug resistance test results, chemistries, hepatitis testing, and urinalysis; reproductive history (age of menarche, sexual activity, contraceptive use, history of previous pregnancies and diagnosed sexually transmitted infections); psychosocial data (HIV disclosure status, substance abuse, sexual history, caregiver data); and mortality data. Edit checks were embedded electronically with each question. For example, laboratory values had a range of acceptable values. The Westat data manager questioned values entered outside of the range with the onsite data abstractor. Westat site monitor, CDC project officers visited each site at least yearly for random audits and compared data abstractions with the medical chart to ensure compliance with the study protocol.

Participant selection

The description of psychiatric history and the analysis of ART adherence problems included all LEGACY participants with perinatally acquired HIV infection (defined as HIV infection acquired in utero, intrapartum, or via breastfeeding) with completed longitudinal data abstraction from HIV diagnosis through 2006. We limited our analysis to those participants who were 13 years of age or older on the day of their most recently abstracted clinic visit, a proxy for onset of adolescence, given that youth in this age group are likely to be interested in sex, be in charge of taking their own medication, or be able to obtain illicit substances. In addition, participants who were ART-naïve at the time of the last abstracted clinic visit were also excluded from this analysis.

Assessment of HIV clinical outcomes

HIV-1 RNA serum concentrations and serum CD4+ cell counts from the time of HIV diagnoses through the last LEGACY visit were obtained from the clinical records. The HIV-1 RNA values below 400 copies per milliliter were considered undetectable. Based on the 1994 CDC Pediatric Immunologic Classification,17 which includes categories for various pediatric age groups, CD4+ count values above 500 cells per milliliter were classified as CDC HIV Immunologic category 1 (no evidence of suppression). Values between 200 and 500 cells per milliliter were classified as CDC HIV Immunologic category 2 (moderate suppression) and the values below 200 cells per milliliter were classified as CDC HIV Immunologic category 3 (severe suppression). The CD4 count ranges for three 1994 CDC Pediatric Immunologic Categories for children 6–12 years of age are identical to those for the three Stages of HIV Infection for persons 13 years of age and older in the revised 2008 CDC surveillance HIV case definition.18

Assessment of psychiatric diagnosis history

We defined medically documented psychiatric diagnosis as the presence of one or more psychiatric diagnoses in the medical record at baseline or any follow-up visit through 2006. The abstractors were instructed to abstract the verbal descriptions of diagnoses (e.g., depression, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]) along with any ICD-9 codes exactly as written by the provider. If no ICD-9 code accompanied the verbal description in the medical record, abstractors were instructed to assign a corresponding ICD-9 code. Both the verbal description and ICD-9 code with ICD-9 description are retained in the LEGACY database.

We were unable to review mental health records that were generated as a result of seeing a mental health provider due to IRB restrictions, but were allowed to collect psychiatric diagnoses that appeared in the general medical record. Included in this group were written descriptions and ICD-9 codes used to designate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV TR) mood disorders, psychotic disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, somatoform disorders, all disorders classified as “disorders typically first diagnosed in childhood and adolescence” in the DSM-IV TR19 and a history of encephalopathy (HIV-related or other). Disorders from the DSM-IV TR category “Substance-related disorders” were not included among psychiatric disorders.

Assessment of risky health behaviors

Preadult sexual activity

Sexual activity was defined as preadult if it occurred prior to 18 years of age. The participants were classified as sexually active if one of the following was documented in their medical records: (1) self-reported consensual sexual activity, (2) the participant was a female who had been pregnant, or (3) the participant was a male who had fathered a child or made a female pregnant. Recorded history of sexual abuse was not considered as sexual activity for this analysis.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence problems

We abstracted ART adherence problems which were documented in the clinical notes. LEGACY data collection forms allowed for documentation of HIV medication adherence issues in three ways. (1) The “HIV Medications” form had an adherence checkbox beside every medication entered. The box was to be checked if there was ever an adherence problem with this particular medication due to any reason. (2) The “Medication Stop Reasons” form included “adherence problem” as one of multiple possible reasons for stopping an ARV. (3) The “Medication Adherence” form had a question asking if an unspecified adherence problem was documented by the provider. The participants were considered as having history of ART adherence problems if at least one of these boxes in any of the three forms were checked.

Substance abuse during study period

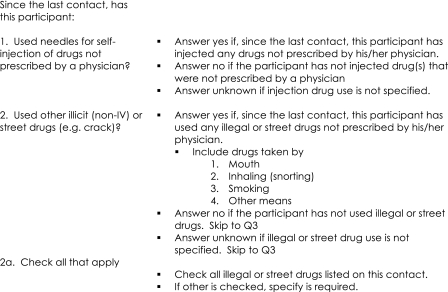

Data collection forms assessing substance abuse behaviors during the study period included an itemized checklist that prompted the abstractors to respond to specific inquiries about the use of amyl nitrite, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, crack, heroin, inhalants, ketamine, LSD, marijuana, MDMA, methamphetamines, sexual stimulants (e.g., Viagra®, Pfizer, New York, NY; Levitra®, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Montville, NJ), smoking cigarettes, having a “drinking problem,” or having been referred for substance abuse rehabilitation. The response choices were yes/no/unknown for each item. A participant was defined as having a history of substance use during study period if they ever had documentation of use of any items on the checklist in the problem list or clinical progress notes. Figure 1 shows a copy of instructions to the abstractors for collecting substance abuse variables that were provided in the LEGACY instruction manual for abstractors.

FIG. 1.

Copy of instructions to the abstractors for collecting substance abuse variables (from the LEGACY instruction manual for abstractors).

Statistical methods

Bivariate associations between the medically documented psychiatric diagnoses and various demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample were performed with the χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, and univariate logistic regression. Logistic regression was used to model all outcomes, including adherence problems, substance abuse, sexual activity, and one or more risky health behaviors. Participant age, gender and race/ethnicity were included as covariates in the adherence problems and one or more risky health behaviors models to control for any associations between these demographics and the outcomes. No covariates were included in the sexual activity and substance abuse models because there were not enough recorded events to support more than one predictor.20 Because a large proportion of participants were black non-Hispanic or Hispanic, we dichotomized ethnicity by Hispanic versus non-Hispanic ethnicity. Based on bivariate tables, Hispanic participants appeared to possess a greater likelihood of association with these outcomes. To assess the logistic regression models, we used bootstrap replications to evaluate the stability of estimated coefficients21 and the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test22 to evaluate the fit of for multivariable models. All tests and confidence intervals were based on the 5% level of significance. SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

There were 575 participants with complete longitudinal data abstraction. Of these, 378 were excluded from the analysis due to one or more of the following reasons: having a nonperinatal mode of HIV transmission (n=180), being younger than 13 years at their last LEGACY visit (n=236), or being ART-naïve at their last LEGACY visit (n=21). Of the remaining 197 participants, 110 (56%) were female, 100 (51%) were black non-Hispanic, and 86 (44%) were Hispanic (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic and HIV-Related Clinical Characteristics by Medically Documented Psychiatric Diagnosis in the LEGACY Cohort, United States, 2001–2006 (N=197)

| |

|

Psychiatric diagnosis(n, % of overall) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall, n (%) | Yes 108 (55) | No 89 (45) | p Value |

| Age at last visit [mean (SE)] | 16.7 (0.3) | 16.9 (0.3) | 0.72 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 110 (56) | 56 (51) | 54 (49) | 0.21 |

| Male | 87 (44) | 52 (60) | 35 (40) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 100 (51) | 60 (60) | 40 (40) | 0.30 |

| Hispanic | 86 (44) | 44 (51) | 42 (49) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 9 (5) | 3 (33) | 6 (67) | |

| Othera | 2 (1) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | |

| Most recent VL copies/mLb | ||||

| <400 | 78 (40) | 42 (54) | 36 (46) | 0.17 |

| 400–10,000 | 54 (27) | 35 (65) | 19 (35) | |

| ≥10,000 | 65 (33) | 31 (48) | 34 (52) | |

| Mean VL copies/mL | ||||

| <400 | 28 (14) | 19 (68) | 9 (32) | 0.31 |

| 400–10,000 | 74 (38) | 40 (54) | 34 (46) | |

| ≥10,000 | 95 (48) | 49 (52) | 46 (48) | |

| Most recent CD4+ cell count | ||||

| ≤200 | 44 (22) | 22 (50) | 22 (50) | 0.79 |

| 200–350 | 24 (12) | 13 (54) | 11 (46) | |

| 350–500 | 33 (17) | 17 (52) | 16 (48) | |

| >500 | 96 (49) | 56 (58) | 40 (42) | |

| CDC immunologic category based on most recent CD4+ count | ||||

| 1) No evidence of suppression | 110 (56) | 65 (33) | 45 (23) | 0.24 |

| 2) Moderate suppression | 46 (23) | 25 (13) | 21 (11) | |

| 3) Severe suppression | 41 (21) | 18 (9) | 23 (12) | |

| CDC immunologic category based on nadir CD4+ cell count | ||||

| 1) No evidence of suppression | 35 (18) | 21 (60) | 14 (40) | 0.79 |

| 2) Moderate suppression | 60 (30) | 32 (53) | 28 (47) | |

| 3) Severe suppression | 102 (52) | 55 (54) | 47 (46) | |

Other, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Mixed Race, and unknown.

VL, HIV-1 RNA serum concentration (viral load).

SE, standard error; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Protection.

Medically documented psychiatric diagnoses

Among the 108 (55%) participants with at least one medically documented psychiatric diagnosis, 60 (55%) had 1 diagnosis, 32 (27%) had 2 diagnosis, and 16 (15%) had 3 or more diagnoses. These 108 participants had a total of 197 medically documented psychiatric diagnoses that can be classified into 9 diagnostic categories (Table 2). The most frequent among these 197 psychiatric diagnoses were mood disorders (n=49, 25%), (ADHD; n=33, 17%) and disruptive behavior disorders (n=30, 15%; Table 2). The corresponding prevalence of these three disorders among the 108 participants was (n=49, 45%) mood disorders, (n=33, 31%) ADHD, and (n=30, 28%) disruptive behavior disorders.

Table 2.

Overview of Medically Documented Psychiatric Diagnoses/Diagnostic Categories in the LEGACY Cohort, United States, 2001–2006

| Psychiatric diagnosis or diagnostic category | Frequency (%) (N=197 psychiatric diagnoses) n (%) | Frequency (%) of participants with psychiatric diagnosis (N=108 participants with ≥ 1 psychiatric diagnosis) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mood disordersa | 49 (25) | 49 (45) |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 33 (17) | 33 (31) |

| Disruptive behavioral disordersb | 30 (15) | 30 (28) |

| Assumed HIV-related encephalopathy | 22 (11) | 22 (20) |

| Developmental disorders/delaysc | 21 (11) | 21 (19) |

| Anxiety disordersd | 10 (5) | 10 (9) |

| Adjustment disorders | 7 (4) | 7 (7) |

| Elimination disorderse | 4 (2) | 4 (4) |

| Otherf | 6 (2) | 6 (6) |

Depressive disorders (296.xx, 300.4, 311) and bipolar disorders (296.xx, 301.13).

Oppositional defiant disorder (313.810, conduct disorder (312.8x), and disruptive behavior disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) (312.9).

Includes mental retardation (DSM-IV TR codes 317-318.x), learning disorders (315.00-315.2, 315.9), communication disorders (307.0, 307.9; 315.3x) and pervasive developmental disorders (299.xx).

Panic disorders (300.01, 300.21), phobias (300.22-300.29), obsessive-compulsive disorder (300.3), posttraumatic stress disorder (309.81), acute stress disorder (308.3), generalized anxiety disorder (300.02), anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition (293.84), and anxiety disorder NOS (300.00).

Enuresis (307.6) and encopresis (307.7).

This category included 1 participant with anxiety/depression due to physical condition (293.84), 1 with schizoaffective disorder (295.70), 1 with affective psychosis NOS (296.90), 2 with eating disorder NOS (307.50), and 1 with “other encephalopathy” (348.39).

HIV clinical outcomes (Table 1)

Most recent HIV-1 RNA serum concentration (viral load or VL) was undetectable in 40% of participants (n=78). Based on their most recent CD4+ count, the most participants had either no evidence of immunologic suppression (CDC HIV Immunologic category 1; n=110, 56%) or evidence of moderate immunologic suppression (CDC HIV Immunologic category 2; n=41, 21%). Based on a nadir CD4+ count, most participants were categorized as having had either severe immunologic suppression (CDC Immunologic category 3; n=102, 52%) or evidence of moderate immunologic suppression (CDC HIV Immunologic category 2; n=60, 30%). Participants with or without psychiatric diagnoses did not differ significantly in relation to their virologic or immunologic clinical outcomes, including the most recent or mean VL, or CDC HIV Immunologic category based on the most recent or nadir CD4+ cell counts (Table 1).

Risky health behaviors

Among 197 participants included in the analysis, 142 (72%) had adherence problems, 12 (6%) had preadult sexual activity and 17 (9%) had a record of substance abuse. One hundred forty-six (74%) participants had a history of at least one of these three aforementioned risky health behaviors. Twenty-four (12%) participants had more than one of the three risky health behaviors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Behavioral Outcomes by Medically Documented Psychiatric Diagnoses, the LEGACY Cohort, United States, 2001–2006 (N=197)

| |

|

Psychiatric diagnoses[n, % of total with risky behavior(s)] |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risky health behavior(s) | Total n (%) | Yes | No | p Value |

| 108 (55) | 89 (45) | |||

| Adherence problems | 142 (72) | 83 (77) | 59 (66) | 0.10 |

| Preadult sexual activity | 12 (6) | 8 (7) | 4 (4) | 0.39 |

| Substance abuse | 17 (9) | 12 (11) | 5 (6) | 0.17 |

| One or more risky health behavior(s) | 146 (74) | 87 (81) | 59 (66) | 0.02 |

| Two or more risky health behavior(s) | 24 (12) | 16 (15) | 8 (9) | 0.21 |

Relationship between medically documented psychiatric diagnoses and risky health behaviors

Bivariate analyses

In bivariate analyses (Table 3), having an individual risky health behavior (adherence problems, preadult sexual activity, or substance abuse) was not associated with a medically documented psychiatric diagnosis. However, a history of having had one or more of the three specified behaviors was more common among participants with (n=87, 81%) than among those without a medically documented psychiatric diagnosis (n=59, 66%; p=0.02).

Logistic regression analysis

Logistic regression models for the individual and combined risky behaviors are shown in Table 4. Having a medically documented psychiatric diagnosis was associated with a history of at least one of three specified risky behaviors (odds ratio [OR]=2.33, p=0.01). Having a medically documented psychiatric diagnosis was not associated individually either with a history of substance abuse during the study period (OR=2.10, p=0.18) or preadult sexual activity (OR=1.70, p=0.40), but was close to being significantly associated with a history of adherence problems (OR=1.85, p=0.07; Table 4)

Table 4.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Models for Effects of Medically Documented Psychiatric Diagnoses on History of Risky Health Behaviors, the LEGACY Cohort, United States, 2005–2006. (N=197)

| Predictor | Category | Odds ratio | 95% Lower confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit | Wald χ2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence problemsa | ||||||

| Age | (none) | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.33 | 5.73 | 0.02 |

| Gender | Male | 0.95 | 0.50 | 1.28 | 0.02 | 0.88 |

| Female | (ref.) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | Hispanic | 1.57 | 0.81 | 3.03 | 1.78 | 0.18 |

| Non-Hispanic | (ref.) | |||||

| Psychiatric disorders | Yes | 1.85 | 0.96 | 3.54 | 3.40 | 0.07 |

| No | (ref.) | |||||

| Substance abuse | ||||||

| Psychiatric disorders | Yes | 2.10 | 0.71 | 6.21 | 1.80 | 0.18 |

| No | (ref.) | |||||

| Preadult sexual activity | ||||||

| Psychiatric disorders | Yes | 1.70 | 0.49 | 5.84 | 1.08 | 0.40 |

| No | (ref.) | |||||

| One or more risky behaviorsb | ||||||

| Age | (none) | 1.22 | 1.06 | 1.40 | 7.67 | 0.006 |

| Gender | Male | 1.06 | 0.54 | 2.08 | 0.03 | 0.87 |

| Female | (ref.) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | Hispanic | 1.49 | 0.75 | 2.95 | 1.31 | 0.25 |

| Non-Hispanic | (ref.) | |||||

| Psychiatric disorders | Yes | 2.33 | 1.18 | 4.60 | 5.95 | 0.01 |

| No | (ref.) | |||||

Goodness of fit statistic: χ2 (8)=4.12, p=0.85.

Goodness of fit statistic: χ2 (8)=6.35, p=0.61.

Participant age had a significant covariate effect on some of the outcomes in the multivariable analyses. With each additional year of age, participants possessed higher likelihoods of adherence problems (OR=1.17, p=0.02) and one or more risky behaviors (OR=1.22, p=0.006). Gender and ethnicity did not show significant covariate effects on any of the outcomes.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between medically documented psychiatric diagnoses and a history of three selected risky health behaviors (i.e., ART adherence problems, preadult sexual activity and substance abuse) in 197 youth with perinatally acquired HIV infection who were 13 years and older at the time of their last recorded LEGACY visit. Fifty-five percent of the participants had documented psychiatric diagnoses which were found to be significantly associated with having a history of at least one of the three risky health behaviors. This association appears to be primarily driven by adherence problems which was by far the most prevalent of the three. This finding validates intuitive concerns of most clinicians caring for children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV infection.6

Given the broad nature of the risk category psychiatric diagnosis (including all DSM-IV TR psychiatric disorders except substance abuse disorders), it would be premature to propose specific mechanisms for this association. We can speculate, however, that non-specific factor(s) associated with a history of psychiatric diagnosis are playing an important role in ART adherence problems in this population. These may be generic features of most psychiatric disorders, such as some degree of impaired decision making or difficulty in balancing various priorities. The environmental factors that have been associated with psychiatric disorders in HIV-infected youth, such as a low level of maternal education, unstable housing or poverty6,8,9,11,23 might play a role as well. Alternatively, symptoms associated with specific psychiatric disorders could contribute uniquely to developing risky health behaviors. For example, medication adherence might be negatively affected by ADHD-related distractibility, depression-related lack of motivation, anxiety-driven concerns about potential medication side effects, paranoid beliefs about the medication, etc.

Preadult sexual activity and substance abuse were not significantly associated with medically documented psychiatric diagnoses, possibly due to low frequencies of these two behaviors and resulting insufficient statistical power. The prevalence of substance abuse in the sample was very low, only 9%. This is consistent with findings from another study that interviewed perinatally HIV-infected youth and their caregivers in the United States11 but is inconsistent with the rates reported by the CDC 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS). YRBS is an anonymous survey, which revealed that 38% of U.S. urban high school students had reported a history of marijuana abuse.24 Similarly, the prevalence of preadult sexual activity of 6% in our study was substantially lower than reported rates of sexual activity (47.8%)24 in the general urban high school population in the United States. This discrepancy is possibly due to differing study methodologies; a higher prevalence of risk behavior is documented in studies such as the YRBS where participants were able to anonymously report information about such risky behaviors, whereas the other referenced cohort study relied on chart abstraction and interviews led by the health care provider, which likely biased results due to underreporting of such risky behaviors. Medical providers may be more likely to inquire about ART adherence rather than the other two health behaviors and, if not asked, patients may be less likely to report the behaviors. Our clinical experience also suggests that pediatric HIV health care specialists may sometimes fill the role of a parent figure for some long-term surviving, and often orphaned, perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. These adolescents may find it just as difficult to share information about their substance use or sexual behaviors with health care providers as many adolescents do with their biological parents. On the other hand, it is also possible that perinatally HIV-infected youth are less sexually active than their uninfected peers, due to stigma of disclosure to partner, avoidance of the risk of possibly infecting another person, or fear of acquiring another STD that could further compromise their immune system. Finally, since many perinatally HIV-infected youths in the United States have received continuous psychosocial support and developmentally appropriate health education since early childhood, it might be that these services have been somewhat effective in the reduction of overall rates of substance abuse and preadult sexual activity in this population.

The findings from this analysis imply that perinatally HIV-infected children with a history of psychiatric diagnoses should be carefully screened for the presence of all three risky health behaviors studied here. Improved identification of such behaviors might help prevent further HIV transmission or development of resistant strains of the virus. Because psychiatric disorders can limit learning capacity, impair judgment or diminish capacity to plan or negotiate safe behaviors, clinicians and health educators caring for HIV-infected youth should remain especially mindful of psychiatric disorders and their association with risky behaviors. Individual, patient-centered educational interventions (e.g., flashcards, reminders, role playing, assertiveness training, and assigning a peer counselor) should probably be considered as methods to accommodate any learning or skill deficits and to increase the likelihood that information imparted during education will be retained as well as implemented by these youth.

This study has strengths and limitations. This longitudinal observational cohort study provides data from a large sample of participants from 22 pediatric and adolescent HIV specialty clinics of varying sizes across the country. Because it is an observational study with few exclusion criteria, it likely provides more representative data than the typical clinical trial. It also includes key longitudinal data on perinatally HIV-infected children from birth through the end of 2006. While these strengths are important, it is important to acknowledge the study's limitations as well. First, we were unable to review participant mental health records but rather collected mental health information that appeared in the clinic or hospital medical record, thus our estimates of psychiatric diagnoses may be an underestimate. Due to limitations in variable definitions and the nature of observational studies, we could not assess the timing of the risky health behaviors in relation to the psychiatric diagnoses and cannot infer causality. As a result, we cannot attribute any directionality in the association between having a psychiatric diagnosis and exhibiting a risky behavior assessed in this analysis. The study was also subject to reporting bias which may have affected the reporting of substance abuse and pre-adult sexual activity. Therefore, the prevalence of substance abuse and pre-adult sexual activity observed in this study likely represent an underestimate.

In conclusion, findings from the present study suggest that perinatally HIV-infected youth who have a history of psychiatric diagnoses are more likely to practice at least one of the three reported risky behaviors than those without a psychiatric diagnosis. As the lifespan of perinatally HIV-infected youth in the HAART era is dramatically increasing, this finding is clinically relevant as it has implications for HIV prevention and public health education. The finding also highlights the importance of examining both HIV-related clinical outcomes as well as psychiatric outcomes in both longitudinal cohort studies and behavioral intervention studies of HIV-infected youth. Future researchers exploring relationships between individual psychiatric disorders and risky health behaviors should ensure that critical mental health information is reported in a standardized fashion both in the mental health and general medical records to minimize ascertainment bias and should utilize anonymous self-reporting by participants as a source of information regarding sexual activity and substance abuse in perinatally HIV-infected youth.

Footnotes

Contributed patient data to 2006 cohort only.

Contributed patient data to all LEGACY cohorts.

Acknowledgments

We thank investigators and abstractors at the LEGACY study sites: Edward Handelsman, Hermann Mendez, Jeffrey Birnbaum, Betsy Eastwood, Diana Mason, Ava Dennie, Gail Joseph (SUNY Downstate, Brooklyn, NY*), Ninad Desai, Liberato Lao (Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY*) Andrew Wiznia, Joanna Dobroszycki, Tina Alford (Jacobi Medical Center, Bronx, NY**), Lisa-Gaye Robinson, Tina Alford (Harlem Hospital, New York City, NY**), Arry Dieudonne, Peggy Latortue (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ*), Tamara Rakusan, Sarah McLeod, Deborah Rone (Children's National Medical Center, Washington, D.C.**), Richard Rutstein, Ariane Adams, Rebecca Thomas, Olivia Prebus (The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA**), George K. Siberry, Allison Agwu, Rosanna Setse, Jenny Chang (The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes, Baltimore, MD**), Steven Nesheim, Sheryl Henderson, Vickie Grimes, Julianne Gaston (Emory University, Atlanta, GA**), Clemente Diaz, Francisca Cartagena (University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico**), Delia Rivera, Dianne Demeritte (University of Miami, Miami, FL**), Jose Carro, William Blouin, Vivian Hernandez-Trujillo, Marcelo Laufer, Dianne Demeritte (Miami Children's Hospital, Miami, FL**), Ana Puga, Yanio Martinez (Children's Diagnostic and Treatment Center, Fort Lauderdale, FL*), Patricia Emmanuel, Janet Sullivan, AJ Sikes, (University of South Florida, Tampa, FL*), Mobeen Rathore, Ana Alvarez, Ayesha Mirza, Kristy Champion, Ellen Trainer (University of Florida, Jacksonville, FL**), Mary E. Paul, Samuel B. Foster, Amy Leonard (Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX**), Gloria Heresi, Gabriela del Bianco (University of Texas-Houston, Houston, TX**), Theresa Barton, Janeen Graper (University of Texas-Southwestern/Children's Medical Center, Dallas, TX**), Toni Frederick, Andrea Kovacs, Suad Kapetanovic, Michael Neely, LaShonda Spencer, Mariam Davtyan, Uhma Ganesan (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA**), Marvin Belzer, Molly Flaherty (Children's Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles CA*), Jane Bork, Mariam Davtyan (Loma Linda University Medical Center, Loma Linda CA*), Dean A. Blumberg, Lisa Ashley, Molly Flaherty (University of California Davis Children's Hospital, Sacramento, CA**).

We thank Kathy Joyce, Julie Davidson, Sharon Swanigan, Patrick Tschumper, Amanda Fournier and Kathleen Paul at Westat Inc. (Rockville, MD) for contractual support, site monitoring and data management support. We also thank Vicki Peters (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene) who has served as a consultant to the LEGACY project.

We are grateful to the patients and caregivers who consented to participate in LEGACY, as well as the administrative personnel at each study site, Westat and the CDC.

Funded through CDC Solicitation No. 2004-N-01211 and prime contract #200-2004-09976 with Westat Inc.

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Kapetanovic contributed to this article in his personal capacity. The views expressed are his own and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or United States Government.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kapetanovic S. Leister E. Nichols S, et al. Relationship between markers of vascular dysfunction and neurodevelopmental outcomes in perinatally HIV-Infected youth. AIDS. 2010;24:1481–1491. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a241b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith Fawzi MC. Eustache E. Oswald C, et al. Psychosocial functioning among HIV-affected youth and their caregivers in Haiti: Implications for family-focused service provision in high HIV burden settings. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santamaria EK. Dolezal C. Marhefka SL, et al. Psychosocial implications of HIV serostatus disclosure to youth with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:257–264. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vreeman RC. Nyandiko WM. Ayaya SO. Walumbe EG. Marrero DG. Inui TS. The perceived impact of disclosure of pediatric HIV status on pediatric antiretroviral therapy adherence, child well-being, and social relationships in a resource-limited setting. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:639–649. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oland A. Valdez N. Kapetanovic S. Process-oriented biopsychosocial approach to disclosing HIV status to infected children. NIMH Annual International Research Conference on the Role of Families in Preventing and Adapting to HIV/AIDS, Providence; Rhode Island. Oct;2008 . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donenberg GR. Pao M. Youths and HIV/AIDS: Psychiatry's role in a changing epidemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:728–747. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166381.68392.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozyce ML. Lee SS. Wiznia A, et al. A behavioral and cognitive profile of clinically stable HIV-infected children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:763–770. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellins CA. Smith R. O'Driscoll MS, et al. NIH/HIAID/NICHD/NIDA-Sponsored Women and Infant Transmission Study Group (2003). High rates of behavioral problems in perinatally HIV-infected children are not linked to HIV disease. Pediatrics. 2003;111:384–393. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malee K. Williams P. Montepiedra G, et al. Medication adherence in children and adolescents with HIV Infection: Associations with behavioral impairment. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:191–200. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chernoff M. Nachman S. Williams P, et al. Mental health interventions in HIV-Infected and uninfected children and adolescents enrolled in PACTG P1055. Pediatrics. 2009;124:627–636. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellins CA. Brackis-Cott E. Leu CS, et al. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:1131–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown LK. Danovsky MB. Lourie KJ. DiClemente RJ. Ponton LE. Adolescents with psychiatric disorders and the risk of HIV. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1609–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Upadhyaya HP. Managing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the presence of substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 11):23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fidalgo TM. da Silveira ED. da Silveira DX. Psychiatric comorbidity related to alcohol use among adolescents. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:83–89. doi: 10.1080/00952990701764664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the psychiatric assessment and management of physically ill children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:213–233. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181908bf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudy BJ. Murphy DA. Harris DR. Muenz L. Ellen J. Prevalence and interactions of patient-related risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among perinatally infected youth in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:97–104. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age. MMWR. 1994;1994;43:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Revised Surveillance Case Definitions for HIV Infection Among Adults, Adolescents, and Children Aged <18 Months and for HIV Infection and AIDS Among Children Aged 18 Months to <13 Years—United States, 2008. MMWR. 2008;57:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peduzzi P. Concato J. Kemper E. Holford TR. Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steyerberg EW. Harrell FE., Jr Borsboom GJ. Eijkemans MJ. Vergouwe Y. Habbema JF. Internal validation of predictive models: Efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:774–781. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosmer DW. Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd. New York: John Wiley & Sons; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudy BJ. Murphy DA. Harris DR. Muenz L. Ellen J. Patient-Related Risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among hiv-infected youth in the United States: A study of prevalence and interactions. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:185–194. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, June 4, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59:SS–5. [Google Scholar]