Abstract

One bottleneck in NMR structure determination lies in the laborious and time-consuming process of side-chain resonance and NOE assignments. Compared to the well-studied backbone resonance assignment problem, automated side-chain resonance and NOE assignments are relatively less explored. Most NOE assignment algorithms require nearly complete side-chain resonance assignments from a series of through-bond experiments such as HCCH-TOCSY or HCCCONH. Unfortunately, these TOCSY experiments perform poorly on large proteins. To overcome this deficiency, we present a novel algorithm, called NASCA (NOE Assignment and Side-Chain Assignment), to automate both side-chain resonance and NOE assignments and to perform high-resolution protein structure determination in the absence of any explicit through-bond experiment to facilitate side-chain resonance assignment, such as HCCH-TOCSY. After casting the assignment problem into a Markov Random Field (MRF), NASCA extends and applies combinatorial protein design algorithms to compute optimal assignments that best interpret the NMR data. The MRF captures the contact map information of the protein derived from NOESY spectra, exploits the backbone structural information determined by RDCs, and considers all possible side-chain rotamers. The complexity of the combinatorial search is reduced by using a dead-end elimination (DEE) algorithm, which prunes side-chain resonance assignments that are provably not part of the optimal solution. Then an A* search algorithm is employed to find a set of optimal side-chain resonance assignments that best fit the NMR data. These side-chain resonance assignments are then used to resolve the NOE assignment ambiguity and compute high-resolution protein structures. Tests on five proteins show that NASCA assigns resonances for more than 90% of side-chain protons, and achieves about 80% correct assignments. The final structures computed using the NOE distance restraints assigned by NASCA have backbone RMSD 0.8 – 1.5 Å from the reference structures determined by traditional NMR approaches.

Keywords: Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), side-chain resonance assignment, nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) assignment, residual dipolar coupling (RDC), protein structure determination

1 Introduction

Recent development of probe technology and fast NMR methods based on sparse sampling has reduced the time constraints of NMR data collection. Therefore, the laborious and lengthy process of resonance assignment is increasingly recognized as the main bottleneck for high-resolution structure determination by NMR.

Most NMR structure determination techniques use NOE distances as the main geometric constraints to elucidate the high-resolution structure of a target protein. A nearly complete set of both backbone and side-chain resonance assignments are generally required to assign inter-proton NOE distance restraints from NOESY spectra. In addition to NOE distance restraints, other types of NMR restraints can also be used in structure determination. For example, residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) provide global orientational restraints on internuclear vectors (Tolman et al. 1995, Tjandra & Bax 1997) and can also be used in structure determination (Tolman et al. 1995, Fowler et al. 2000, Ruan et al. 2008, Prestegard et al. 2004, Donald & Martin 2009, Wang & Donald 2004, Wang et al. 2006, Zeng et al. 2009).

Although substantial progress has been made in automated backbone resonance assignment (Zimmerman et al. 1997, Bailey-Kellogg et al. 2000, Coggins & Zhou 2003, Langmead et al. 2003, Eghbalnia et al. 2005, Wu et al. 2005, Bailey-Kellogg et al. 2005, Kamisetty et al. 2006, Vitek et al. 2006), only a handful of algorithms have been developed for automated NOE assignment (Zeng et al. 2009, Herrmann et al. 2002, Gronwald et al. 2002, Linge et al. 2003, Huang et al. 2006, Kuszewski et al. 2008), and little progress has been made for automated side-chain resonance assignment (Lin & Wagner 1999, Montelione & Moseley 1999, Baran et al. 2004, Fiorito et al. 2008). In practice, neither resonance assignment nor NOE assignment is an easy task, since NMR spectra are often complicated by spectral artifacts, missing peaks, experimental noise and peak overlap. Generally speaking, the side-chain resonance assignment problem is much more challenging than the backbone resonance assignment problem (Montelione & Moseley 1999, Baran et al. 2004, Masse et al. 2006). Traditional approaches for side-chain resonance assignment (Li & Sanctuary 1996, 1997, Pons & Delsuc 2001, Masse et al. 2006) usually require a combination of several side-chain NMR experiments, such as HCCH-TOCSY experiments, to obtain nearly complete side-chain resonance assignments for high-resolution structure determination. Unfortunately, TOCSY-based experiments usually perform poorly on large proteins due to the fast transverse relaxation of protonated carbons, which causes severe signal loss in NMR spectra. Partially deuterated protein samples with selective methyl proton labelling have been used to reduce transverse relaxation for large proteins (Goto et al. 1999, Tugarinov et al. 2006) and improve the efficiency of structure determination for small proteins (Zheng et al. 2003, Tang et al. 2010). Although partial protein deuteration improves sensitivity and resolution of NMR spectra, it also reduces the number of the NMR-active protons attached to side-chain carbons, thus limiting the utility of the HCCH-TOCSY experiment for obtaining complete side-chain resonance assignments. However, it is essential to obtain nearly complete side-chain resonance assignments as a prerequisite for high-resolution structure determination. Therefore, development in side-chain resonance assignment and high-resolution structure determination without TOCSY data is highly valuable and can potentially enable structural studies of large proteins by NMR.

In this paper, we describe a novel algorithm, called NASCA (NOE Assignment and Side-Chain Assignment), that assigns both side-chain resonances and NOE distance restraints from NOESY spectra. Our algorithm takes as input NOESY spectra, backbone chemical shifts, and RDCs, but does not require any TOCSY-type experiments. It casts the assignment problem into a Markov Random Field (MRF) framework, and applies combinatorial protein design algorithms to compute the optimal solution that best interprets (matches) the NMR data. We first apply our recently-developed techniques (Wang & Donald 2004, Wang et al. 2006, Donald & Martin 2009, Zeng et al. 2009) to compute the protein backbone using mainly RDC restraints. Then NASCA uses the RDC-defined backbone conformations plus all possible side-chain conformations from a rotamer library to construct the contact map information and derive the MRF. A Hausdorff-based computation is incorporated in the scoring function to compute the probability of side-chain resonance assignments to generate the observed NOESY spectra. The optimal side-chain resonance assignments are computed using protein design algorithms (Desmet et al. 1992, Looger & Hellinga 2001, Goldstein 1994, Georgiev et al. 2008, Chen et al. 2009). First, a dead-end elimination (DEE) algorithm (Desmet et al. 1992, Looger & Hellinga 2001, Goldstein 1994) is applied to prune side-chain resonance assignments that are provably not part of the optimal solution. Second, an A* search algorithm is employed to find a set of optimal side-chain resonance assignments that best fit the NMR data. These computed optimal side-chain resonance assignments are then used in the MRF to resolve the NOE assignment ambiguity. Note that MRFs and other graphical models have been used in structural and computational biology (Yanover & Weiss 2002, Kamisetty et al. 2008). Often they are used with techniques such as belief propagation (Yanover & Weiss 2002), which can only be proven to compute a local optimum for a general graph. In contrast, we use DEE and A* algorithms to provably compute the global optimal solution to the MRF.

In our assignment problem, the “optimal” solution means the set of side-chain resonance assignments that minimize the scoring function defined in the MRF framework. These optimal assignments are equivalent to the best mappings (which minimize the scoring function) from unassigned chemical shifts to side-chain proton identities, each of which includes the residue number, the proton name (e.g., Hγ2 of Lys42) and the side-chain rotamer identity (e.g., mtt180°) of side-chain protons. The optimal solution is important even if it is only the optimum “in the model” (i.e., not “biologically”), since it represents the set of side-chain resonance assignments that best interpret the NMR data. In practice, three levels of approximation are used in computing the optimal side-chain resonance assignments. (1) A rotamer library is used to model the discrete side-chain proton positions based on the RDC-defined backbone. (2) An MRF is used to derive the scoring function that measures the probability of side-chain resonance assignments given the NMR data. (3) In the derived scoring function for measuring the probability of side-chain resonance assignments, the RDC-defined backbone is considered as rigid.

Previously, we proposed a high-resolution structure determination approach using an RDC-defined backbone conformation and a pattern-matching technique (Zeng et al. 2009). A preliminary version of our algorithm was presented in a conference abstract (Zeng et al. 2010). Unlike the algorithm in (Zeng et al. 2009) and other automated structure calculation approaches (Güntert 2003, Herrmann et al. 2002, Linge et al. 2003, Huang et al. 2006, Kuszewski et al. 2004), all of which require a nearly complete set of both side-chain and backbone resonance assignments, the high-resolution structure determination strategy encoded by NASCA only needs backbone resonance assignments, and does not require any explicit through-bond experiment, such as HCCH-TOCSY, to facilitate side-chain resonance assignment. The distinct advantage of our algorithm over traditional structure calculation approaches (Güntert 2003, Herrmann et al. 2002, Linge et al. 2003, Huang et al. 2006, Kuszewski et al. 2004) is that in our algorithm, the global fold defined by the global orientational restraints from RDCs is employed in an MRF framework to resolve assignment ambiguity from the NOESY data exclusively. Since the NOESY data is not largely used in defining the global fold, to some extent our method avoids the circularity that NOEs are used to define the fold, but the fold is needed to assign the NOEs.

2 Methods

2.1 The Basic Concept

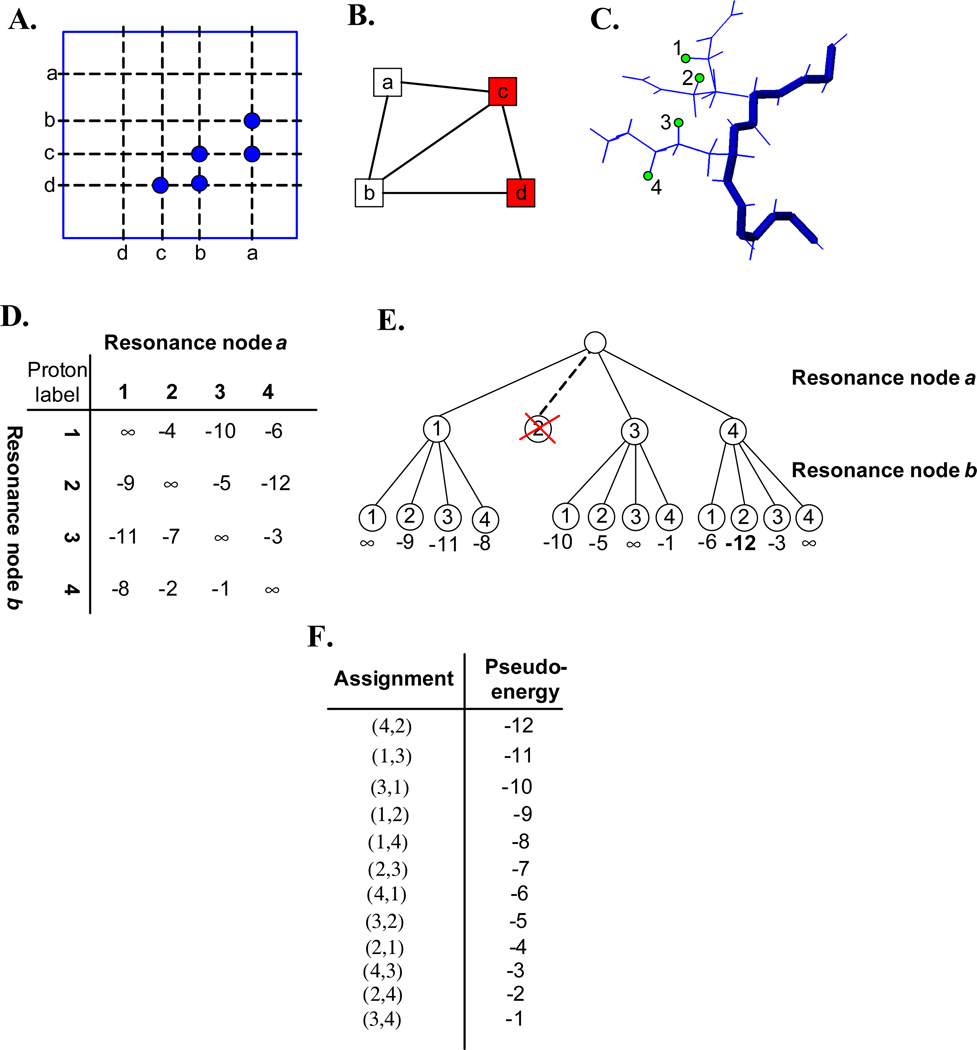

We first illustrate the basic idea of our MRF framework using a toy example (Fig. 1). In Sec. 2.2, we give an overview of NASCA by schematically illustrating the major steps in the algorithm. In our toy example, suppose that the backbone resonances have been assigned and given as input data. In addition, we assume that the backbone structure has been determined at least to medium resolution using primarily RDCs (see Sec. 2.3). Suppose that we have two unassigned side-chain resonances a and b, and two assigned backbone resonances c and d. We want to assign these two side-chain resonances a and b. We first construct a graph (Fig. 1B) based on the NOESY spectrum shown in Fig. 1A. In this graph, the node set includes nodes a, b, c and d, and each edge represents a possible NOE interaction between a pair of resonances. We consider all possible discrete positions of side-chain protons by placing all side-chain rotamer conformations on the RDC-defined backbone. As we describe below, these possible discrete side-chain positions are called proton labels. For clarity, we only show four proton labels, denoted by 1, 2, 3 and 4 in our example, where 1 and 2 have the same proton name but belong to different rotamer conformations. The example can be extended to the general case in which all discrete side-chain rotamer conformations are considered. In this simple example, we must map the unassigned resonance nodes a and b to proton labels 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Figure 1.

A toy example to illustrate the basic idea of the MRF framework. (A): Cartoon NOESY spectrum. Resonances are represented by lower case letters, and NOESY cross peaks are shown in blue circles. For clarity, symmetric and diagonal peaks are not shown. (B): The NOESY graph. Unassigned side-chain resonance nodes are represented by white squares, while assigned backbone resonance nodes are represented by red squares. (C): The proton labels. The backbone structure is shown in blue stick, and side-chain rotamers are shown in blue line. Each green circle represents a side-chain proton label. (D): The pairwise pseudo-energy matrix. (E): Complete enumeration of side-chain resonance assignments for nodes a and b using the A* algorithm after the DEE pruning. Assignments of resonance nodes a and b are represented by the branches in the first and second tiers respectively. Node marked with red X is pruned by the DEE algorithm from further consideration. The number at the bottom of each leaf node is the pseudo-energy of the corresponding assignments. The minimum pseudo-energy of the optimal assignments is shown in boldface. (F): All resonance assignments in order of increasing pseudo-energy.

We formulate this assignment problem into an MRF. In an MRF, the conditional dependence between random variables is formulated as an undirected graph, and each random variable is conditionally dependent only on the random variables of its neighbors in this graph. In our problem, the resonance assignments for side-chain resonances a and b in the graph shown in Fig. 1B are defined as random variables. The assignment of each side-chain resonance only depends on the resonance assignments of its neighbors in the NOESY graph. For example, in Fig. 1B, the resonance assignment of node a is only dependent on the resonance assignments of its neighbors, nodes b and c. The probability for each possible resonance assignment conditioned on the assignments of its neighbors can be measured by comparing the corresponding back-computed NOE pattern to the NOESY spectra.

For each assignment combination of resonance nodes a and b, we compute the pseudo-energy using the scoring function derived below in Eq. (7). The reader is referred to Secs. 2.4 and 2.5 for more details on computing the pseudo-energy. We assign a positive infinity value to each diagonal element in the matrix, since a proton label cannot be simultaneously assigned to two resonance nodes connected by an edge in the NOESY graph. The pairwise pseudo-energy matrix for all possible resonance assignments of a and b is shown in Fig. 1D. Here each entry in the matrix is the pseudo-energy for the corresponding assignments of a and b. For example, the pseudo-energy is −10, when resonance node a is assigned to proton label 3 and resonance node b is assigned to proton label 1. Our aim is to find the optimal assignments that yield the minimum pseudo-energy. To achieve this goal, we first use the dead-end elimination (DEE) algorithm to prune those assignments that are provably not part of the optimal assignments. For example, for the assignment from resonance node a to proton label 2, there exists another assignment from resonance a to proton label 1, such that for all possible assignments of resonance b, the latter assignment (i.e., from resonance a to proton label 1) always has a better pseudo-energy (see Fig. 1D). The efficient pruning using DEE reduces the complexity of our problem, and enables us to combinatorially search over the remaining possible side-chain resonance assignments and find the optimal solution (Fig. 1E). After DEE pruning, we apply the A* algorithm to enumerate all combinations of remaining resonance assignments, and find the optimal assignments with the minimum pseudo-energy. As shown in Fig. 1E, the minimal pseudo-energy is −12, corresponding to the assignments from resonance node a to proton label 4, and from resonance node b to proton label 2. We can also enumerate the possible assignments, in order of energy, using the A* algorithm. Fig. 1F lists all resonance assignments of a and b in a gap-free order of increasing pseudo-energy. Each resonance assignment is represented by a pair of numbers in parentheses, where the first number is the proton label assigned to resonance a, and the second number is the proton label assigned to resonance b. The first assignment in Fig. 1F is the optimal assignment (4,2) with the minimal pseudo-energy.

2.2 Overview

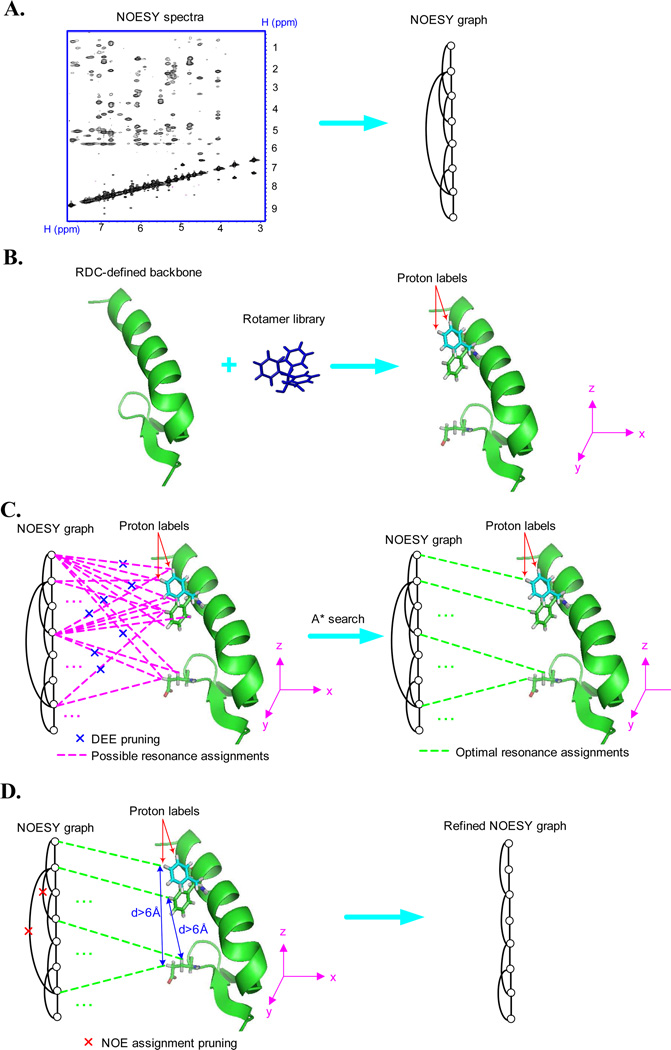

In the previous section, we illustrated the basic concept of MRFs using a simple example (Fig. 1). Our algorithm is divided into four steps (Fig. 2). In the first step (Fig. 2A), NASCA constructs a graph, called NOESY graph (Bailey-Kellogg et al. 2000, 2005), to represent the contact map information of the protein from the NOESY spectra. In a NOESY graph, each node represents an assigned backbone or unassigned side-chain proton chemical shift, and each edge represents a possible NOE interaction between a pair of proton chemical shifts indicated from the NOESY spectra. This step corresponds to Fig 1A and Fig 1B in our toy example given in Sec. 2.1. In the second step (Fig. 2B), NASCA places all side-chain rotamer conformations on the RDC-defined backbone, and obtains a set of all possible discrete positions for each side-chain proton. Those discrete side-chain proton positions are called proton labels, which represent all possible proton positions in ℝ3 after considering the backbone conformation and all side-chain rotamer conformations. Our goal is to map the unassigned chemical shift nodes in the NOESY graph to side-chain proton labels such that the back-computed NOE pattern derived from the mappings best fit the NOESY spectra. In the third step (Fig. 2C), we formulate this mapping problem into an MRF and apply protein design algorithms, including dead-end elimination (DEE) and A* search algorithms to compute the optimal side-chain resonance assignments. We call the joint assignment probabilities of all side-chain resonance nodes in an MRF the probability or distribution of the MRF. It might appear difficult to compute the probability of an MRF. Fortunately, the Hammersley-Clifford theorem (Hammersley & Clifford 1971, Besag 1974) provides a simple way to compute the probability of an MRF. It is equivalent to computing the probability of a Gibbs distribution, which can be factored over the cliques (or complete subgraphs) of the underlying graph (i.e., the NOESY graph in our case).

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration on the four major steps of NASCA. (A): Construction of the NOESY graph. (B): Construction of proton labels. (C): The side-chain resonance assignment process. (D): The NOE assignment process. An example of Steps (A), (B) and (C) is described in Fig. 1.

The Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) (Ulrich et al. 2007) has collected statistics on observed chemical shifts of all amino acids from a large database of solved protein structures. We call this information the BMRB statistical information. The maximum and minimum chemical shifts of an atom derived from the BMRB statistical information are called the BMRB limits of this atom. The interval within the maximum and minimum chemical shifts of an atom is called the BMRB interval of this atom. This information is often used to assist both backbone and side-chain resonance assignments (Atreya et al. 2000, Wu et al. 2005, Pons & Delsuc 2001). We use Bayes’ rule to combine the probability of side-chain resonance assignments and the BMRB statistical information. The derived posterior probability leads to a scoring function that measures how well a set of side-chain resonance assignments fit the NMR data conditioned on the BMRB statistical information. Now the problem is reduced to finding the set of side-chain resonance assignments that maximize the posterior probability. Such side-chain resonance assignments are called the optimal assignments, which best interpret the NMR data given our MRF model. As we will show, the derived scoring function contains a pairwise term representing an NOE interaction between a pair of protons. Such a pairwise pseudo-energy term is similar to the pairwise energy function used in the protein design field. Thus, protein design algorithms can be applied here to solve our side-chain resonance assignment problem. Specially, NASCA first uses dead-end elimination (DEE) to prune side-chain resonance assignments that are provably not part of the optimal solution, and then applies the A* search algorithm to search over the remaining combinations of side-chain resonance assignments and find the set of assignments that optimize the scoring function. In the last step (Fig. 2D), the set of optimal side-chain resonance assignments are used to resolve NOE assignment ambiguity, and derive the unambiguous NOE distance restraints. For each edge in the original NOESY graph, NASCA checks whether the distance between each pair of assigned proton labels is larger than the distance upper bound calculated from the peak intensity. An NOE assignment is pruned if the corresponding distance is violated. The remaining edges in the NOESY graph are output as the set of NOE distance restraints for final high-resolution structure calculation.

2.3 Backbone Structure Determination from Residual Dipolar Couplings and Sparse NOEs

Residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) provide global orientational restraints on the internuclear vectors with respect to an external magnetic field (Tolman et al. 1995, Tjandra & Bax 1997), and have been used to determine protein backbone conformations (Tolman et al. 1995, Fowler et al. 2000, Tian et al. 2001, Rohl & Baker 2002, Prestegard et al. 2004, Wang & Donald 2004, Wang et al. 2006, Ruan et al. 2008, Donald & Martin 2009). We applied our recently-developed algorithms (Wang & Donald 2004, Wang et al. 2006, Zeng et al. 2009, Donald & Martin 2009) to compute the backbone structures using two RDCs per residue (either NH RDCs measured in two media, or NH and CH RDCs measured in a single medium) and sparse NOE distance restraints. In previous work, these algorithms were used prospectively, in bona fide structure determination (Zeng et al. 2009). In our backbone structure determination, we first computed conformations and orientations of secondary structure element (SSE) backbones from RDC data using the RDC-ANALYTIC algorithm (Wang & Donald 2004, Wang et al. 2006, Donald & Martin 2009, Zeng et al. 2009). Instead of randomly sampling the entire conformation space to find solutions consistent with the experimental data, RDC-ANALYTIC computes the backbone dihedral angles exactly by solving a system of quartic monomial equations derived from the RDC equations (Wang & Donald 2004, Wang et al. 2006, Donald & Martin 2009, Zeng et al. 2009). A depth-first tree search strategy is applied to search systematically over all roots of a system of low-degree (quartic) equations, and find a globally optimal solution for each SSE fragment. These RDC-defined SSE backbone fragments are then assembled using a sparse set of inter-SSE NOE distance restraints (Wang & Donald 2004, Wang et al. 2006, Donald & Martin 2009, Zeng et al. 2009). The loop structures are computed using a local minimization approach (Zeng et al. 2009), in which the SSE backbones are fixed as a rigid body, while loops and side-chains are allowed to move. A set of sparse long-range NOEs are also included in the local minimization approach to compute the loop conformations. Here we do not use the HANA module (which performed NOE assignment) in our previous structure determination package RDC-PANDA (Zeng et al. 2009), since it requires the side-chain resonance assignments.

The following procedure is used to extract sparse NOEs from the NOESY data. Initially we pre-assign a small number (< 15) of side-chain resonances using the input backbone chemical shifts and expected (intra-residue or sequential) NOE interactions within the local covalent distance. In these expected NOE interactions, two protons are always within the NOE upper limit distance regardless of the dihedral angles, and hence are supposed to generate observable cross peaks in NOESY spectra. The set of pre-assigned side-chain resonances are then used to extract sparse long-range NOEs from NOESY data. Here we illustrate this procedure using a detailed example from protein FF2 with the real data. We first filter the assignments of Hβ protons using the input chemical shifts of attached heavy atoms Cβ and the known BMRB limit information, which leads to a set of unambiguous assignments of Hβ protons. For example, we assign frequencies 1.22 ppm and 1.67 ppm to protons Hβ of residue Leu52 in FF2, since they are the only frequencies that both fall within the BMRB interval and have the frequency of heavy atom overlapping with the input chemical shift of Cβ atom. After that, we identify a small set of unambiguous side-chain resonance assignments using the expected local NOE interactions from backbone protons HN, Hα and Hβ to side-chain protons within the local covalent distance. As in the above example, since the side-chain protons Hδ in residue Leu52 are always within the NOE upper limit distance from protons Hα and Hβ in the same residue, NOE cross peaks are supposed to be observed in NOESY spectra between side-chain protons Hδ and backbone protons Hα and Hβ. From the NOESY data of FF2, we assign frequency 0.84 ppm to protons Hδ in residue Leu52, since it both falls into the corresponding BMRB interval and has the NOE interactions with both Hα and Hβ of residue Leu52. Next, combined with the input backbone chemical shifts, these pre-assigned side-chain resonances are used to extract sparse NOEs from the NOESY data, using a parameterized error window for each chemical shift dimension. We identify a small number (< 50) of unique NOE assignments, in which each NOESY peak is only assigned to a pair of backbone or side-chain chemical shifts within the parameterized error windows (0.04 ppm for protons and 0.4 ppm for heavy atoms attached to protons). These unique NOE assignments are considered as unambiguous NOE distance restraints for packing SSEs. At this stage, no information on backbone conformations is used in assigning these sparse NOE restraints.

Using global orientational restraints from RDCs, plus the above sparse distance restraints extracted from NOESY data, we are able to compute a global fold (i.e., backbone) to medium resolution. Our previous studies (Zeng et al. 2009) demonstrated that our backbone structure determination approach can compute a global fold with backbone RMSD 1.24±0.55 Å for the core structure (i.e., packed SSE backbone conformations) and 1.47±0.41 Å for the entire backbone structure. More details on our backbone structure determination approach can be found in (Donald & Martin 2009, Wang & Donald 2004, Wang et al. 2006, Zeng et al. 2009). Currently, our method is required to compute the RDC-defined backbone before proceeding to side-chain resonance assignment. In principle, a different structure determination software/algorithm could also be used to bootstrap the structure-based assignment. In practice, our backbone structure determination approach can compute good structures using the sparse data (viz., Table 4), while traditional SA/MD-based approaches, such as XPLOR-NIH, cannot guarantee to converge to an ensemble of decent structures, as we will show in the Discussion Section (and Fig. 7), using the same data.

Table 4.

Summary of the sparse data used to compute the initial global fold. These data include RDCs, sparse NOEs extracted from the NOESY data to pack SSEs, and dihedral angle restraints derived from TALOS (Cornilescu et al. 1999).

| Proteins | ubiquitin | hSRI | FF2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of RDCs (in one medium) | 37 CH RDCs; 37 NH RDCs. |

45 CH RDCs; 46 NH RDCs. |

30 CH RDCs; 32 NH RDCs; 31 CαC’ RDCs; 33 NC’ RDCs; |

| # of sparse NOEs | 3 | 11 | 11 |

| # of TALOS angle restraints | 36 | 89 | 62 |

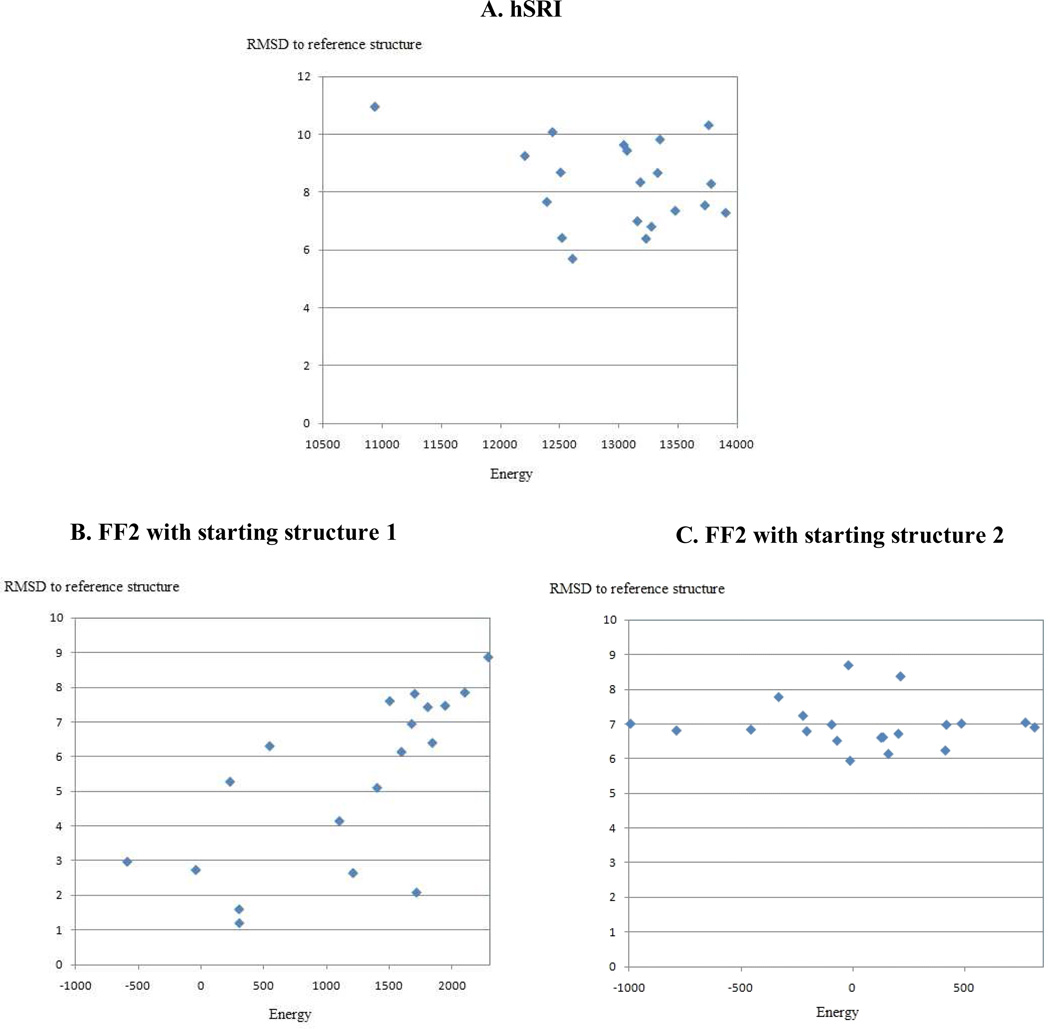

Figure 7.

Plots of energy vs. SSE backbone RMSD to NMR reference structure for hSRI and FF2 structures computed by XPLOR-NIH, using the sparse data in Table 4. (A): Plot of hSRI. (B) and (C): Plots of FF2 with different starting structures used in the RDC refinement step. Top 20 structures with the lowest energies among total 100 structures computed by XPLOR-NIH are plotted here. The backbone RMSD between the mean coordinates and the NMR reference structure for SSE regions is 7.3 Å, 5.7 Å and 6.9 Å for plots (A), (B) and (C) respectively. These results show that XPLOR-NIH failed to bootstrap the initial global fold calculation using the sparse data in Table 4.

2.4 Markov Random Field for Side-Chain Resonance Assignment

We introduce notation to describe our side-chain resonance assignment problem. Let U = {r1, ⋯, rn} be the set of all resonances, including both backbone and side-chain resonances. Here backbone resonances are assigned and taken as input to our algorithm. Side-chain resonances are, of course, unassigned. Let t be the number of unassigned side-chain resonances, so the number of assigned backbone resonances is n − t. Without loss of generality, let V = {r1, ⋯, rt} be the set of unassigned side-chain resonances, and let U − V = {rt+1, ⋯, rn} be the set of assigned backbone resonances.

A graph G = (U, E), called the NOESY graph (Bailey-Kellogg et al. 2000, 2005), represents the contact map information of resonances from NOESY spectra. In a NOESY graph G = (U, E), U is the set of proton resonances (including both assigned backbone and unassigned side-chain proton resonances). Two resonances in U are connected by an edge in E, when a NOESY cross peak is observed at the coordinates (within a parameterized error window) of these two resonances. Nodes in U are called the resonance nodes (or resonances). Given a resonance node u in a NOESY graph G = (U, E), N(u) = {υ | (u, υ) ∈ E and u, υ ∈ U, u ≠ υ} is called the neighborhood of u. In the 2D NOESY spectra, the set of unassigned side-chain resonances can be obtained by projecting the 2D cross peaks into the proton frequency dimension. In the 3D case, we can also extract the frequency of the heavy atom bond-connected to each proton from the 3D NOESY spectra, which can hence reduce the number of noisy edges in the NOESY graph. Thus, in the 3D case, we use the frequencies of proton and its attached heavy atom to represent a resonance node in the NOESY graph. In NASCA, the list of unassigned side-chain resonances are extracted from 3D NOESY spectra by projecting all 3D NOE cross peaks into the plane of the first and second dimensions (i.e., the dimensions of the first proton and its bond-connected heavy atom).

A proton label is defined as a 3-tuple that consists of the proton name (e.g., Arg16-Hγ2), the rotamer identity (e.g., the mtt180° rotamer for arginine) and the proton coordinates in ℝ3. The set of all proton labels is called the label set L of the NOESY graph. We obtain a discrete and finite label set by considering all possible side-chain rotamer conformations on the RDC-defined backbone. Since the backbone has been solved and each side-chain rotamer conformation is rigid, each proton label corresponds to a proton on a particular rotamer after being placed on the backbone (with fixed positions in ℝ3 with respect to backbone conformation). In our assignment problem, we aim to find a map π : V → L, such that the contact map information through the mapped resonance nodes in a NOESY graph optimally interprets NOESY spectra. Given a resonance node ri ∈ V and a map π, we call π(ri) ∈ L a proton label assignment (or assignment) of ri. Given a sequence of resonances W = (r1, ⋯, rm), we call the sequence (π(r1), ⋯, π(rm)) an assignment of W, where π(ri) is the assignment of resonance node ri.

Unlike previous side-chain resonance assignment algorithms (Li & Sanctuary 1996, 1997, Pons & Delsuc 2001, Masse et al. 2006, Fiorito et al. 2008), which only assign proton names to resonances, our algorithm NASCA computes not only the resonance assignments but also the rotamer assignments, since each proton label contains both the proton name and the rotamer identity of this proton. The rotamer assignments included in the proton label assignments yield an ensemble of side-chain rotamer conformations for each residue, which are unified by the logical “OR” operation. In NASCA, proton labels are treated as a cloud of unconnected points in ℝ3. This formulation is similar to (Grishaev & Llinás 2002a,b) which uses a spatial proton distribution to represent a gas of unbound and unassigned hydrogen atoms. Unlike (Grishaev & Llinás 2002a,b), which depends on molecular dynamics to embed the structure from the unassigned proton density, NASCA exploits the RDC-defined backbone conformations and applies an MRF to compute the correspondence between side-chain resonances and protons. Although the absence of the covalent structure in proton labels may allow resonances to map to the protons on the same side-chain in different rotameric states, NASCA takes into account the distance information of the covalent structure when computing the probability of side-chain resonance assignments (Sec. 2.5). In practice, as we will show in Sec. 3, our MRF can compute a high percentage of correct side-chain resonance assignments for accurate structure determination.

Given a NOESY graph, the assignment of each unassigned resonance ri only depends on the resonance assignments of its neighborhood N(ri) in G. We can use a Markov Random Field (MRF) model (Kindermann & Snell 1980) to encode this assignment problem. The assignment of a resonance node ri satisfies the following property:

| (1) |

where Pr(·) is the probability of an event, and N(ri) is the set of resonance nodes adjacent to ri in the graph.

According to the Hammersley-Clifford theorem (Hammersley & Clifford 1971, Besag 1974), the distribution of an MRF can be written in a closed form. Let C be a clique in the underlying graph G, and let TC(·) be a clique potential (Besag 1974) that represents the probability of a particular assignment of all resonance nodes in clique C. Let V′ = (r1, ⋯, rt) be an ordered sequence of resonances from set V = {r1, ⋯, rt}. Let F = (π(r1), ⋯, π(rt)) be an assignment for the sequence of resonances V′. By the Hammersley-Clifford theorem, the probability of an assignment F is defined by Pr(F) ∝ exp(−∑C TC(F)). We consider the potential function TC for cliques of size 2, that is, the clique potential involves pairs of neighboring resonance nodes in G. Note that MRFs with cliques of size of 2 have been widely applied in several areas such as computer vision (Boykov et al. 1998) and computational biology (Kamisetty et al. 2008, Wei & Li 2007). In our MRF, Pr(F) measures the distribution of side-chain resonance assignments by capturing the pairwise resonance interactions in NOESY spectra and exploiting the structural information available from the RDC-defined backbone conformations and the discretized side-chain rotamer conformations.

Given two proton labels with the distance between their coordinates less than 6 Å, we expect to observe an NOE peak in NMR spectra. Such an expected peak is called a back-computed NOE peak. In contrast, an NOE peak that has been observed in experimental (NOESY) spectra is called the experimental NOE peak. A back-computed NOE pattern is defined as a set of back-computed NOE peaks. Since each proton label consists of the proton name, the rotamer identity and the discrete coordinates of the rotamer’s side-chain proton, the assignments of a resonance ri and its neighborhood N(ri) determine a back-computed NOE pattern. A back-computed NOE pattern is constructed as follows. Let d(π(ri), π(rj)) be the Euclidean distance between two proton labels π(ri) and π(rj). Let Iij = c · (d(π(ri), π(rj)))−6 be the back-computed peak intensity using distance d(π(ri), π(rj)), where c is the calibration constant that can be computed using the same strategy as in (Mumenthaler et al. 1997, Kuszewski et al. 2004). Let λ(ri) be the resonance of the heavy atom that is covalently bound to the proton corresponding to resonance ri. Given a pair of assignments π(ri) and π(rj), we call bij(π(ri), π(rj)) = (ri, λ(ri), rj, Iij) the back-computed NOE peak of π(ri) and π(rj). The definitions of back-computed NOE peaks here and experimental NOE peaks in Sec. 2.5 are presented for 3D NOESY spectra. They can be easily extended to other dimensional cases (e.g., 4D). When d(π(ri), π(rj)) is larger than the NOE cutoff 6 Å or two proton labels represent the same proton name, the back-computed NOE peak is a null point. Given a set of resonances W ⊂ U and the assignment π, let Bπ(W) = {bij(π(ri), π(rj))|ri, rj ∈ W, ri ≠ rj} be the back-computed NOE pattern of W.

In our MRF formulation, the clique potential for node ri and its neighborhood N(ri) can be measured by the matching score of their back-computed NOE pattern. Specifically, let Vi = {ri} ∪ N(ri), and let Bπ(Vi) be the back-computed NOE pattern of Vi under the assignment π. Without ambiguity, we will use Bi to represent Bπ(Vi). Let s(Bi) be the matching score of the back-computed NOE pattern Bi, where the function s(·) will be defined in Sec. 2.5. We use Tπ(ri, N(ri)) = −s(Bi) to represent the clique potential of the pairwise interactions between ri and its neighborhood N(ri). Thus, we have the following function for the probability of an MRF F = (π(r1), ⋯, π(rt)):

| (2) |

We use Q to represent the BMRB statistical information. To estimate the probability of an MRF F based on the BMRB statistical information Q, we first relate them using the probability function Pr(Q|F). Recall that λ(ri) represents the frequency of the heavy atom covalently bound to the proton corresponding to ri. The probability function Pr(Q|F) is defined by

| (3) |

where P(|x − μ|, σ) is the probability of observing the difference |x − μ| in a normal distribution with mean μ and standard deviation σ. In Eq. (3), μi and σi represent, respectively, the average value and standard deviation for resonance ri, while represent, respectively, the average value and standard deviation for the frequency of the heavy atom covalently bonded to the proton corresponding to ri. The values of μi, σi, are all derived from the BMRB. We note that the normal distribution and other similar distribution families have been widely used to model the noise in the NMR data, e.g., see (Rieping et al. 2005) and (Langmead & Donald 2004a).

By Bayes’ Rule, Pr(F|Q), the probability of the assignment F conditioned on the BMRB statistical information Q (namely the posterior probability), can be computed as follows:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Our goal is to compute an assignment F* = (π*(r1), ⋯, π*(rt)) that maximizes the posterior probability Pr(F|Q). Taking the negative logarithm on both sides of Eq. (6), we have the following pseudo-energy function for an assignment F = (π(r1), ⋯, π(rt)):

| (7) |

The pseudo-energy function in Eq. (7) measures how well an assignment F = (π(r1), ⋯, π(rt)) satisfies both the BMRB statistical information and the experimental NMR data. Maximizing the posterior probability Pr(F|Q) in Eq. (6) is equivalent to minimizing the pseudo-energy function in Eq. (7). We call the assignment F* = (π*(r1), ⋯, π*(rt)), that minimizes the scoring function EF and thus best interprets the NMR data restraints, the optimal assignment or optimal solution to our MRF. Since our proton label assignments contain both resonance assignments and molecular side-chain coordinates, the optimal assignment is analogous to the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC) in the protein design literature.

2.5 The Matching Score of a Back-Computed NOE Pattern

The matching score of a back-computed NOE pattern can be measured by comparing the back-computed peaks with NOESY spectra. Given a set of resonance nodes W ⊂ U and an assignment π, let Bπ(W) denote their back-computed NOE pattern. Without ambiguity, we will use B to stand for Bπ(W). Let Y be the set of experimental peaks. The matching score between the back-computed NOE pattern B and experimental spectrum Y can be measured by the conventional Hausdorff distance H(B, Y) = max(h(B, Y), h(Y, B)), where h(B, Y) = maxb∈B miny∈Y ‖b − y‖ and ‖ · ‖ is the normed distance. This conventional Hausdorff distance is sensitive to a single outlying point of B or Y (Huttenlocher & Kedem 1992, Huttenlocher et al. 1993). For example, suppose that an NOE peak is missing in Y (which is quite common in NMR data), and its corresponding back-computed peak in B has a large distance from any peak in Y. In such a case, the Hausdorff distance between B or Y is dominated by this missing NOE peak. To take into account the missing NOE peaks, we employ a generalized Hausdorff distance measure, called the Hausdorff fraction (fractional Hausdorff distance), which is derived from the kthHausdorff distance hk from B to Y (Huttenlocher et al. 1993, Huttenlocher & Jaquith 1995):

where kth is the kth largest value. Now, let δ be the error window in chemical shift. Then the probability of the back-computed NOE pattern B under hk(B, Y) ≤ δ, is computed by the following Hausdorff fraction equation (Huttenlocher & Jaquith 1995):

| (8) |

where Yδ denotes the union of all balls obtained by replacing each point in Y with a ball of radius δ, and τ (·) denotes the size of a set.

Next, we will show how to compute the matching score of a back-computed NOE pattern in Eq. (8). Let bij(π(ri), π(rj)) = (ri, λ(ri), rj, Iij) be a back-computed NOE peak in B based on assignments π(ri) and π(rj), where π(ri) is the frequency of the heavy atom covalently bound to the proton corresponding to ri, and Iij is the back-computed peak intensity. Without ambiguity, we will use bij to represent bij(π(ri), π(rj)). Note that the distance information of the covalent structure is also included when computing a back-computed NOE pattern, since the distances between protons within a residue or in consecutive residues are generally < 6 Å. Let (x, y, z, I′) be the experimental NOESY cross peak that is closest to the back-computed NOE peak bij under the Euclidean distance measure, where x and z are frequencies of NOE interacting protons, y is the frequency of the heavy atom covalently bound to the first proton, and I′ is the peak intensity. When computing the geometric count τ(B ∩ Yδ), we must take into account the uncertainty in chemical shift. For example, suppose that the back-computed NOE peak bij is within the Euclidean distance δ from an experimental NOESY cross peak. When bij is closer to this experimental peak, it should contribute more to counting τ(B ∩ Yδ). To measure the probability of a back-computed NOE peak to intersect with Yδ, we model the uncertainty of chemical shifts in individual dimensions as independent normal distributions. Formally, the following equation is employed to compute τ(B ∩ Yδ):

| (9) |

where P(|x − μ|, σ) is the probability of observing the difference |x − μ| in a normal distribution with mean μ and standard deviation σ. We define the standard deviations in Eq. (9) as a function of the error window δ. We choose σ = δ/3 for each dimension such that the probability for a back-computed NOE peak outside Yδ to contribute to τ(B ∩ Yδ) is almost 0.

2.6 A DEE Pruning Algorithm

The chemical shift of each proton in a particular residue usually lies within an interval derived from the BMRB statistical information (Ulrich et al. 2007). Therefore, each resonance node ri in the NOESY graph is only allowed to map to a subset of proton labels, in which the BMRB-derived chemical shift intervals contain the frequency of ri. Given a resonance ri, we call the subset of proton labels in L, that ri is allowed to map to, the candidate mapping set of ri, denoted by A(ri). When we know the backbone resonance assignments, we have |A(ri)| = 1 for all backbone resonance nodes ri. Given a sequence of resonances W = (r1, ⋯, rm), we call A(W) = (A(r1), ⋯, A(rm)) the candidate mapping set of W. Let D = (π(r1), ⋯, π(rm)), where π(ri) ∈ A(ri) is the assignment of ri. We write D ⋵ A(W) when π(ri) ∈ A(ri) for every i = 1, ⋯, m, i.e., the assignment of ri lies in the candidate mapping sets for all resonances.

We use γ(ri, u) to mean that proton label u ∈ L is assigned to resonance node ri, where u ∈ A(ri). Initially, NASCA prunes any proton label assignment γ(ri, u) in which the frequency of ri falls outside the BMRB-derived chemical shift interval. Let be the set of resonance nodes in the neighborhood of ri, and let be a sequence of resonance nodes in N(ri), where m is the total number of resonance nodes in the neighborhood. Then the candidate mapping set of . Let be an assignment of N′(ri), where , and we use γ(N′(ri), Di) to mean that Di is assigned to N′(ri).

Given an assignment F = (π(r1), ⋯, π(rt)) for the sequence of resonances V′ = (r1, ⋯, rt), we use E(γ(ri, π(ri)) to represent the first energy term in Eq. (7) under the assignment π. We use E(γ(ri, π(ri)), γ(N′(ri), Di)) to represent the second energy term in Eq. (7) when assigning π(ri) to resonance node ri and Di to N′(ri), where π(ri) ∈ A(ri) and Di ⋵ A(N′(ri)). Then the pseudoenergy scoring function in Eq. (7) for an assignment F = (π(r1), ⋯, π(rt)) can be rewritten as

| (10) |

where π(ri) ∈ A(ri) and Di ⋵ A(N′(ri)).

An algorithm that is similar to the GMEC calculation method in protein design (Desmet et al. 1992, Looger & Hellinga 2001, Goldstein 1994, Georgiev et al. 2008, Chen et al. 2009) can be applied here to compute the optimal proton label assignments. The dead-end elimination (DEE) algorithm has been effectively applied to prune rotamers when their contribution to the total energy is always less than another (competing) rotamer (Desmet et al. 1992, Looger & Hellinga 2001, Goldstein 1994, Georgiev et al. 2008, Chen et al. 2009). We use a similar idea in NASCA to prune proton label assignments that are provably not part of the optimal solution. Given an unassigned side-chain resonance node ri ∈ V, a proton label assignment υ ∈ A(ri) is eliminated if an alternative proton label assignment u ∈ A(ri) satisfies the following Goldstein criterion (Goldstein 1994):

| (11) |

Any assignment γ(ri, υ) satisfying Eq. (11) is provably not part of the optimal solution, and thus can be safely pruned. The complexity of computing the Goldstein criterion in Eq. (11) is O(na2w), where n is the total number of resonances, a is the maximum number of proton labels in the candidate mapping set of a resonance, and w is the maximum number of proton labels that can be assigned to a resonance node’s neighborhood. DEE reduces the conformation search space by pruning proton label assignments that can not be in the optimal solution, and provides a combinatorial factor reduction in computational complexity.

2.7 Computing Optimal Side-Chain Resonance Assignments

To compute the optimal solution to our MRF, NASCA applies an A* algorithm (Leach & Lemon 1998, Russell & Norvig 2002, Sun et al. 2007) to search over all possible combinations of the remaining proton label assignments surviving from DEE. An A* algorithm provably finds the optimal (i.e., least-cost) path from a given starting node to the goal node in a search tree or graph. It uses a heuristic cost function to determine the order of visiting nodes during the search. The heuristic cost function consists of two parts: the actual cost from the starting node to the current node, and the estimated cost from the current node to the goal node. Next, we will define both actual and estimated cost functions that are used to determine the order of searching nodes in our A* algorithm.

Recall that V′ = (r1, ⋯, rt) denotes the sequence of unassigned side-chain resonances, and (rt+1, ⋯, rn) denotes the sequence of assigned backbone resonances. Let Xi be the variable representing the assignment of resonance node ri. Similar to the protein design problem (Leach & Lemon 1998, Georgiev et al. 2008), our search configuration space can also be formulated as a tree, in which the root represents an empty assignment, a leaf node represents a full assignment of V′, and an internal node represents a partial assignment of V′ (i.e., only a subsequence of resonances in V′ are assigned). Let H = (Xt+1, ⋯, Xn) be the sequence of known assignments for backbone resonances (rt+1, ⋯, rn). Let S = (X1, ⋯, Xt) be a sequence of assignments for side-chain resonances in V′. Given the BMRB statistical information Q and the known backbone chemical shifts H, the probability for a sequence of side-chain resonance assignments S is

| (12) |

Suppose that the A* algorithm has assigned resonances r1, ⋯, ri−1. We rewrite Eq. (12) as

| (13) |

Taking the negative logarithm on both sides of Eq. (13), we have

| (14) |

Eq. (14) measures the cost of a path from the root (i.e., empty assignment) to one of leaf nodes (i.e., full assignments) in our A* search tree.

Let

| (15) |

which measures the probability of the set of the first i assignments X1, ⋯, Xi, and leads to the actual cost of the path from the root to the current node in the A* search tree.

Let

| (16) |

which estimates the cost of assigning the remaining resonance nodes (i.e., the cost of the path from current node to the leaf nodes in the A* search tree).

Then the cost function in our A* search is defined by

| (17) |

where g is the actual cost from the root to the current node in the search tree, and h is the estimated cost from the current node to one of leaf nodes, in which all side-chain resonances are assigned.

In Eq. (16), Pr(Xj |Xj−1, ⋯, Xi, ⋯, X1, H, Q), j > i, is estimated as follows:

| (18) |

where γ(rj, uj) denotes the assignment of uj to resonance node rj.

The A* algorithm maintains a list of search nodes, which are ranked according to the cost function (Eq. (17)). Similar to the protein design work in (Georgiev et al. 2008), here the A* search algorithm expands the nodes in order of the cost function f. In each iteration, the node with the smallest f value is visited, and the values of f in the remaining nodes are updated. All remaining nodes in the list are re-ordered according to the new f values, and form the children of the current visited node. Such a process is repeated until all side-chain resonances are assigned (i.e., when a leaf node in the search tree is reached).

An estimated cost function is admissible, if it does not overestimate the cost from any node to the goal node. The admissibility of the estimated cost function ensures that an A* search algorithm will find the optimal solution. As shown in (Zeng et al. 2010), the estimated cost function defined in Eq. (18) is admissible, which guarantees that our A* search algorithm will find the optimal side-chain resonance assignments. The A* algorithm is proven to be complete and optimal in searching for the least-cost path (Leach & Lemon 1998, Russell & Norvig 2002, Sun et al. 2007). Although the time complexity of the A* algorithm is exponential in the number of side-chain resonances in the worst case, in practice, our algorithm, including both DEE and A* modules, runs only in hours for a medium-size protein. For instance, it takes about 7 hours to compute the set of side-chain resonance assignments on a single-processor machine for the protein human ubiquitin without human intervention.

2.8 Resolving NOE Assignment Ambiguity

The set of optimal side-chain resonance assignments computed by the A* search algorithm enable an NOE assignment procedure based on the NOESY graph in our MRF framework. After applying DEE and A* search algorithms to obtain the set of optimal side-chain resonance assignments, NASCA uses the following procedure to compute the NOE distance restraints. It first extracts a set of initial NOE assignments from the edges E in the NOESY graph, using the computed side-chain resonance assignments and the input backbone resonance assignments. These initial NOE assignments may contain noisy (i.e., spurious) NOE assignments due to experimental noise or chemical shift overlap. For each possible NOE assignment, NASCA checks whether the distance between the coordinates of assigned side-chain proton labels in the rotamers (after being placed on the backbone) violates the NOE distance bound. An initial NOE assignment is pruned when the Euclidean distance between the coordinates of a pair of assigned proton labels is larger than the NOE distance calibrated from NOE peak intensity (Fig. 2D). Specifically, suppose that the optimal side-chain resonance assignments for ri and rj are π*(ri) and π*(rj) respectively, where proton labels π*(ri) and π*(rj) contain proton coordinates in ℝ3 after placing the corresponding side-chain rotamer conformations on the RDC-defined global fold. Let d(π*(ri), π*(rj)) be the Euclidean distance between proton coordinates of π*(ri) and π*(rj). If d(π*(ri), π*(rj)) is larger than the NOE distance computed from the calibrated peak intensity, the NOE assignment resulting from the edge (ri, rj) is pruned. After all edges in in the NOESY graph have been examined, the set of remaining NOE assignments are output as the NOE assignment table (together with the computed optimal side-chain resonance assignments as the output of our algorithm) for final structure determination. Note that after pruning the violated NOE assignments, two NOE restraints can still be assigned to the same NOESY peak. In this situation, these two NOEs are unified by the logical “OR” operation when being used in structure calculation.

3 Results

We have tested NASCA on NMR data of five proteins: the FF Domain 2 of human transcription elongation factor CA150 (FF2), the B1 domain of Protein G (GB1), human ubiquitin, the ubiquitin-binding zinc finger domain of the human Y-family DNA polymerase Eta (pol η UBZ), and the human Set2-Rpb1 interacting domain (hSRI). The numbers of amino acid residues in these proteins are 62 for FF2, 39 for pol η UBZ, 56 for GB1, 76 for ubiquitin, and 112 for hSRI.

All NMR data except the RDC data of ubiquitin and GB1 were recorded and collected using Varian 600 and 800 MHz spectrometers at Duke University. The NMR spectra were processed using the program NMRPIPE (Delaglio et al. 1995). All NMR peaks were picked by the programs NMRVIEW (Johnson & Blevins 1994) or XEASY/CARA (Bartels et al. 1995), followed by manual editing. Backbone assignments, including resonance assignments of atoms N, HN, Cα, Hα, Cβ, were obtained from the set of triple resonance NMR experiments HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HN(CA)CB, HN(COCA)CB, and HNCO, combined with the HSQC spectra using the program PACES (Coggins & Zhou 2003), followed by manual checking. The NOE cross peaks were picked from three-dimensional 15N- and 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra. In addition, we removed the diagonal cross peaks and water artifacts from the picked NOE peak list. The NH and CH RDC data of FF2, pol η UBZ and hSRI were measured from a 2D 1H-15N IPAP experiment (Ottiger et al. 1998) and a modified (HACACO)NH experimental (Ball et al. 2006) respectively. The CαC′ and NC′ RDC data of FF2 were measured from a set of HNCO-based experiments (Permi et al. 2000). The CH and NH RDC data of ubiquitin were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID of ubiquitin: 1D3Z). For GB1, we computed its global fold using the CH and NH RDC data from a homologous protein, namely the third IgG-binding domain of Protein G (GB3) (PDB ID: 1P7E). The third IgG-binding domain of Protein G (GB3) has 88% sequence identity with the B1 domain of Protein G (GB1). The program BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990) was used to compare two protein sequences and compute the sequence identity score. Our results on GB1 can be considered a good test of using homology modelling to compute the global fold.

NASCA is a new software package developed in our lab. The input data to NASCA include: (1) the protein primary sequence; (2) protein backbone coordinates; (3) the 2D or 3D NOESY peak list from both 15N- and 13C-edited spectra; (4) the backbone chemical shift list; (5) the rotamer library (Lovell et al. 2000).

The input protein backbones were computed mainly using the RDC data (see Section 2.3). We used the method described in Section 2.3 to pre-assign a small number of side-chain resonances and use them to extract sparse NOEs (which involve both backbone and side-chains) from the 3D NOESY data for packing SSEs and computing the initial loop conformations. We used 3–11 sparse NOEs in packing SSEs and < 17 sparse NOEs as the initial distance restraints in the local minimization approach to compute each loop conformation. Similar to (Zeng et al. 2009), the backbone RMSD between the RDC-defined global folds and the reference structures was less than 1.21±0.60 Å for the core structure (i.e., packed SSE conformations) and less than 1.59±0.36 Å for the entire backbone structure. The RMSD between experimental and back-calculated RDCs for the RDC-defined backbone was 1.1±0.9 Hz for CH RDCs and 1.2±1.1 Hz for NH RDCs. These RDC-defined input structures are only medium-resolution and do not contain side-chain conformations. As we will demonstrate, these RDC-defined backbones provide sufficient structural information for side-chain resonance assignment and NOE assignment in our MRF framework.

After we computed the protein backbones from RDCs, we fed them together with the backbone chemical shifts and 3D NOESY peaks into NASCA to compute side-chain resonance assignments and NOE assignments. Next, we will evaluate the accuracies of both side-chain resonance assignments and NOE assignments computed by NASCA.

3.1 Accuracy of Side-Chain Resonance Assignments

We evaluated the accuracy of the side-chain resonances assigned by NASCA by comparing them with the chemical shifts of the proteins that were assigned manually using other additional side-chain NMR experiments. NASCA achieves the completeness of over 90% for resonance assignment, that is, it assigns the resonances of over 90% of protons (Table 1). Note that the manual assignments are usually obtained from TOCSY experiments, while frequencies in our resonance list are extracted from NOESY spectra. Due to the experimental uncertainty, frequencies of our assigned resonances are not exactly equal to the manually-assigned chemical shifts. We used an error window 0.04 ppm for 1H, and 0.4 ppm for heavy atoms (i.e., 13C and 15N) to check whether two resonance assignments agree with each other. We say a resonance assignment is correct if its frequency is within the error window from the reference assignment, which was assigned manually using other additional experiments. Our tests show that NASCA computes about 80% of the correct resonance assignments (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of side-chain resonance assignment results.

| Proteins | GB1 | ubiquitin | hSRI | pol η UBZ | FF2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of residues | 56 | 76 | 112 | 39 | 62 |

| Total number of assignments | 300 | 453 | 606 | 196 | 380 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.0 | 95.4 | 90.3 | 93.3 | 92.5 |

| Correctness (%) | 81.7 | 80.8 | 86.3 | 93.4 | 80.0 |

| Execution time (minute) | 208.4 | 429.1 | 1232.9 | 16.2 | 316.1 |

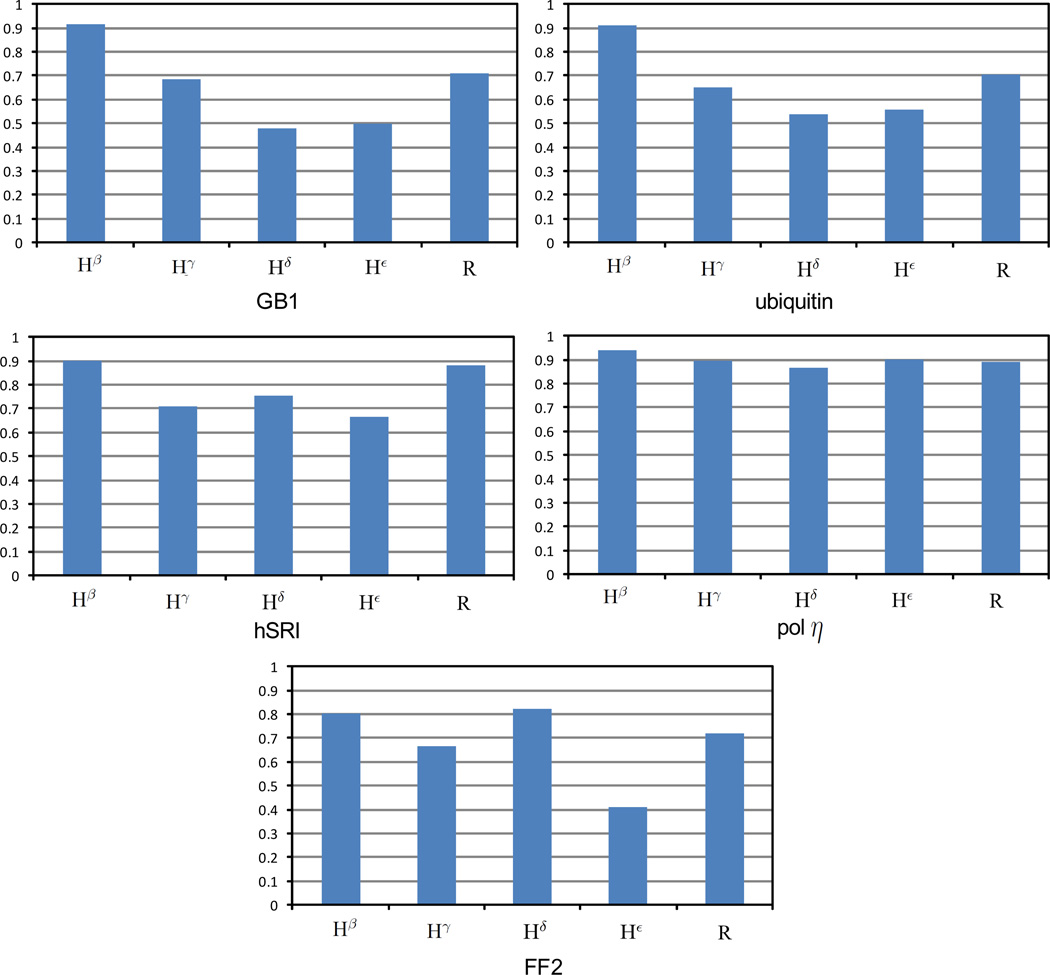

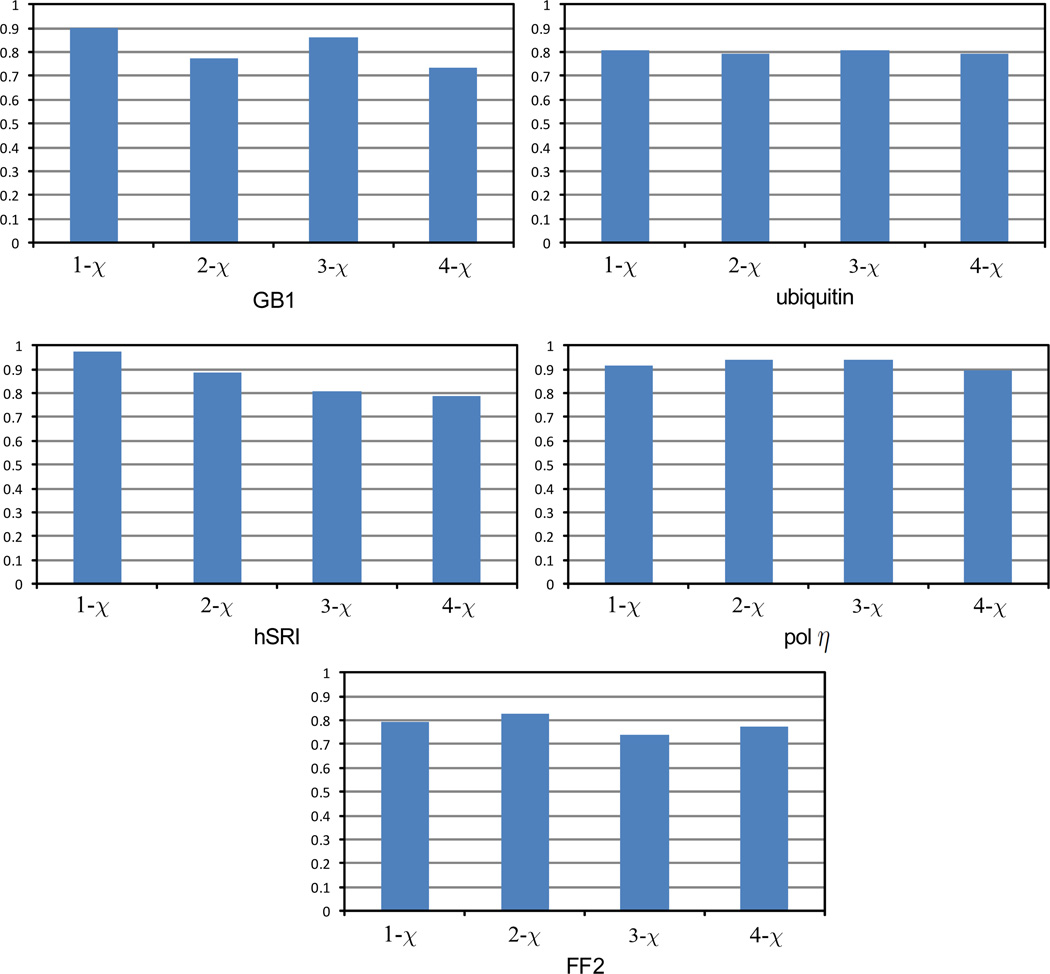

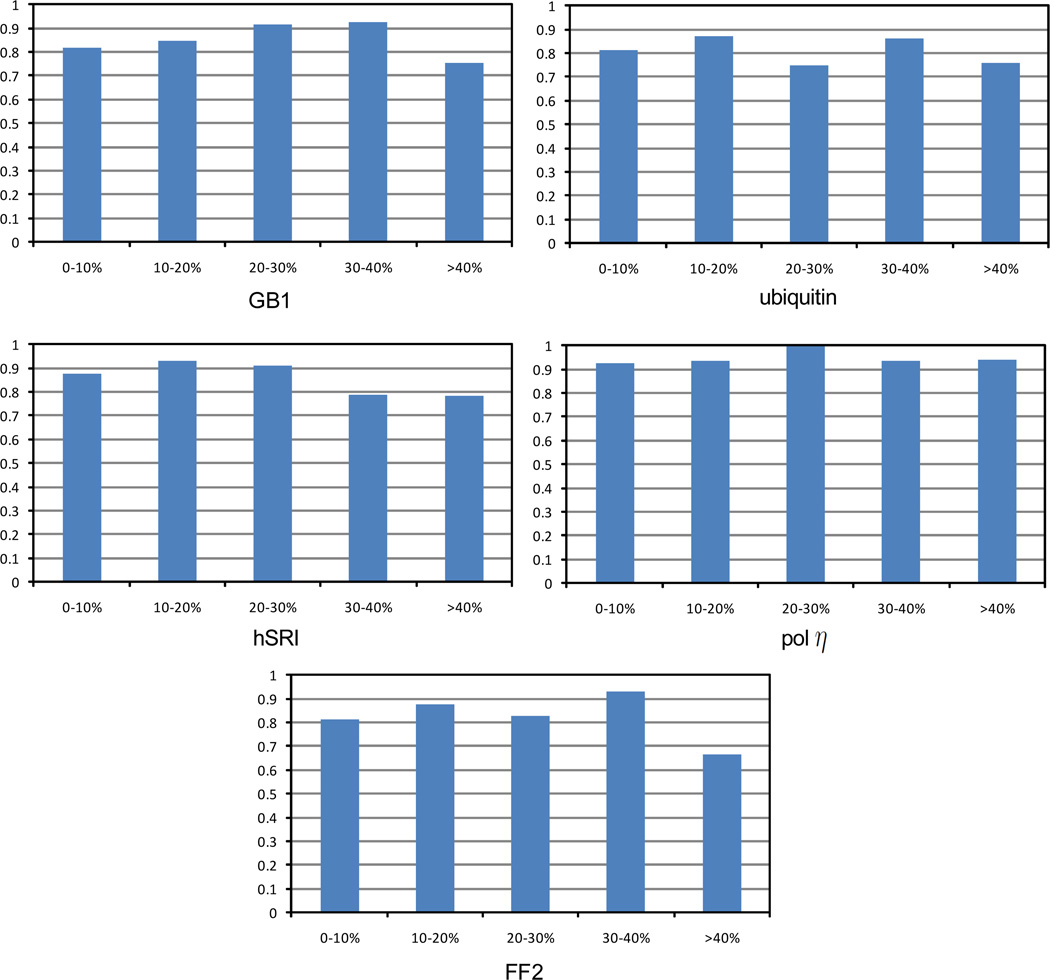

Fig. 3 summarizes the accuracies of resonance assignments for different types of side-chain protons, including Hβ, Hγ, Hδ, Hε and aromatic protons. As indicated in Fig. 3, a decent portion (between 70–90%) of aromatic side-chain resonance assignments agree with the manual assignments. The mis-assignments of aromatic ring protons can be possibly caused by the compact aromatic packing. Aromatic rings are usually packed closely in the 3D Euclidean space. Thus, they can influence the assignments of each other. More incorrect aromatic side-chain resonance assignments occurred in ring protons Hε and Hζ than in ring protons Hδ, which likely reflects the fact that Hδ ring protons have more and stronger NOE cross peaks than Hε and Hζ ring protons, and hence contain more information to identify the correct resonance assignments. For all five proteins, overall Hβ protons achieve the best accuracy (i.e., 89.5±9.1%). Probably this is because the chemical shifts of the bond-connected heavy atom Cβ have been assigned from the backbone resonance assignment. For protein GB1, ubiquitin and pol η UBZ, Hγ protons have the second best assignment accuracy over all other non-aromatic protons. Overall, more Hβ and Hγ protons are assigned correctly than Hδ and Hε protons. In general, Hε has lower assignment accuracy than other types of side-chain protons. This is probably because those Hε protons are on long hydrophilic residues, such as arginine and lysine, which are more exposed to the solvent than other side-chain protons, and hence have fewer NOE interactions with other protons. This indicates that NOESY spectra can only provide limited information for assigning the correct chemical shifts of Hε protons. Such a deficit can make the program easily mis-assign the chemical shift of Hε with other side-chain protons within the same residue, or with other Hε protons in different lysine residues. On the other hand, since each protein usually has a relatively small number of Hε protons, the overall percentage of incorrect Hε resonance assignments among all resonance assignments is small (< 30%).

Figure 3.

Accuracies of resonance assignments for different types of side-chain protons, where R stands for the aromatic protons.

For all five proteins, those incorrect side-chain resonance assignments did not significantly degrade the downstream NOE assignments. This is because they only affect a small number of NOE assignments involving surface residues. In addition, the effect of ambiguous NOE assignments caused by the nearby protons can be absorbed by the uncertainty in NOE upper bounds calibrated from the peak intensities, which do not degrade the protein structure determination process. Further discussion on the incorrect side-chain resonance assignments can be found in Sec. 4. As we illustrate below, the current side-chain resonance assignment table computed by NASCA will yield a sufficient number of accurate NOE assignments for high-quality structure determination.

We also examined the resonance assignment accuracies for different residue types of different lengths. We divided all residues into four classes according to the number of rotatable χ angles in the side-chain conformation. As shown in Fig. 4, for proteins ubiquitin and pol η UBZ, no significant difference in the assignment accuracy is observed for different residue types. In these two proteins, NASCA still assigns a high percentage (about 80%) of resonances for long side-chains, including arginine and lysine. For proteins hSRI and FF2, NASCA performs better on short side-chains (i.e., 1,2-χ residue types) than long side-chains (i.e., 3,4-χ residue types). Overall, the 4-χ type residues, arginine and lysine, have a lower percentage of correct resonance assignments than other residue types. Because arginine and lysine residues are often found on the surface of the protein, and have only a limited number of NOE interactions with other protons, it might be difficult to identify the correct assignments using the scoring function derived based on the NOESY data.

Figure 4.

Accuracies of side-chain resonance assignments for different residue types. The 4-χ type includes asparagine and lysine. The 3-χ type includes methionine, glutamine and glutamic acid. The 2-χ type includes aspartic acid, asparagine, isoleucine, leucine, histidine, phenylalanine, tryptophan and tyrosine. The 1-χ type includes proline, threonine, valine, serine and cysteine.

We further investigated the performance of NASCA on different side-chain protons in different regions of the protein structure. Fig. 5 shows the assignment accuracies for different protons with different solvent accessibilities. Overall, NASCA achieves higher assignment accuracy on the interior and buried protons (with solvent accessibility ≤ 40%) than on the surface protons (with solvent accessibility > 40%). Note that a similar phenomenon was observed in a previous side-chain resonance assignment program ASCAN (Fiorito et al. 2008).

Figure 5.

Accuracies of resonance assignments for side-chain protons with different solvent accessibilities. The solvent accessibility for each proton was computed using the software MOL-MOL (Koradi et al. 1996) with a solvent radius of 2.0 Å.

3.2 Accuracy of NOE Assignments and Effectiveness for High-Resolution Structure Determination

To examine the accuracy of the NOE assignments computed by NASCA, we compared them with the reference structures. We say an NOE assignment is correct if it agrees with the reference structure, that is, the distance between the assigned pair of NOE protons in the reference structure satisfies the NOE restraint whose distance is calibrated from the experimental peak intensity. As shown in Table 2, NASCA computes over 80% correct NOE restraints. To further investigate these NOE distance restraints, we fed them into XPLOR-NIH (Schwieters et al. 2003) to calculate structures. To fairly compare the accuracy of our NOE restraints, we fed the same hydrogen bond and dihedral angle constraints into XPLOR-NIH, as in computing the NMR reference structures. In addition, the structures were refined with RDC data using XPLOR-NIH with a water-refinement protocol (Schwieters et al. 2003).

Table 2.

Summary of NOE assignment results.

| Proteins | GB1 | ubiquitin | hSRI | pol η UBZ | FF2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total # of assigned NOEs | 1466 | 1530 | 3501 | 978 | 1359 |

| Intraresidue | 567 | 630 | 1341 | 380 | 568 |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 295 | 313 | 769 | 232 | 305 |

| Medium-range (|i − j| ≤ 4) | 210 | 195 | 931 | 223 | 322 |

| Long-range (|i − j| ≥ 5) | 394 | 392 | 460 | 143 | 164 |

| Percentage of correct NOE assignments (%) | 87.7 | 83.2 | 84.4 | 86.4 | 85.4 |

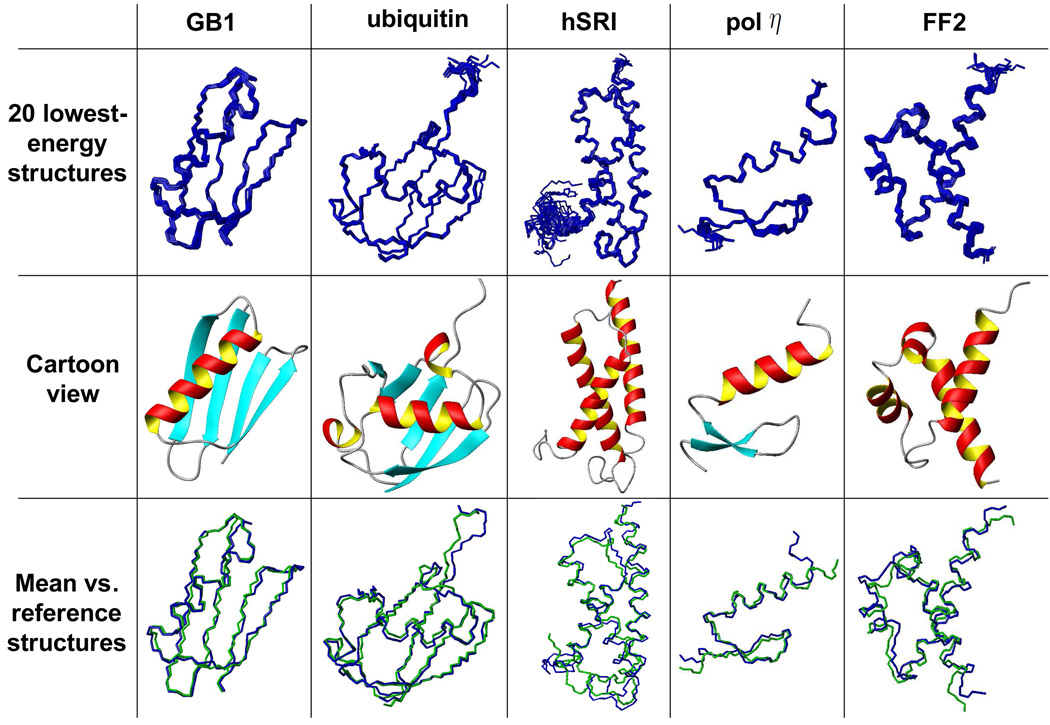

We chose an ensemble of the top 20 structures with the lowest energies out of 50 structures computed by XPLOR-NIH as the ensemble of final structures. For all five proteins, the chosen ensemble converges into a compact cluster (Table 3 and Fig. 6). The average RMSD to the mean coordinates is ≤ 0.4 Å for backbone atoms and ≤ 1.0 Å for all-heavy atoms. The loop regions, especially for the long loop regions, exhibited slightly more disorder than the SSE regions (Fig. 6). We superimposed the mean structure of the ensemble with the reference structure for each protein. The RMSD between the mean structure and the reference structure (ordered region) is 0.8–1.5 Å for backbone atoms and 1.0–2.3 Å for all-heavy atoms (Table 3 and Fig. 6). The RMSD is usually improved when only the SSE regions of the mean structure are superimposed to the reference structure (Table 3). For example, the backbone RMSD for ubiquitin is improved from 0.97 Å to 0.85 Å when only SSE structures are aligned to the reference structure. These results indicate that the NOE assignments computed by NASCA are sufficient for high-resolution structure determination.

Table 3.

Summary of final calculated structures.

| Proteins | GB1 | ubiquitin | hSRI | pol η UBZ | FF2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average RMSD to mean coordinates | |||||

| SSE region (backbone, heavy) (Å) | 0.22, 0.51 | 0.14, 0.43 | 0.27, 0.92 | 0.15, 0.42 | 0.27, 0.73 |

| Ordered region (backbone, heavy) (Å) | 0.27, 0.56 | 0.16, 0.46 | 0.31, 0.93 | 0.22, 0.64 | 0.33, 0.97 |

| RMSD to reference structure | |||||

| SSE region (backbone, heavy) (Å) | 0.77, 1.08 | 0.85, 1.52 | 0.93, 1.54 | 0.86, 1.49 | 0.90,1.80 |

| Ordered region (backbone, heavy) (Å) | 0.81, 1.13 | 0.97, 1.77 | 1.48, 2.21 | 0.80, 1.56 | 1.19, 2.25 |

Figure 6.

Final NMR structures computed using our automatically-assigned NOEs. Row 1: the ensemble of 20 lowest-energy NMR structures. Row 2: ribbon view of one structure in the ensemble. Row 3: backbone overlay of the mean structures (blue) vs. corresponding NMR reference structures (green) (PDB ID of GB1 (Juszewski et al. 1999): 3GB1; PDB ID of ubiquitin (Cornilescu et al. 1998): 1D3Z; PDB ID of FF2: 2E71; PDB ID of hSRI (Li et al. 2005): 2A7O; PDB ID of pol η UBZ (Bomar et al. 2007): 2I5O).

4 Discussion

4.1 Comparisons to Other Methodologies

NASCA differs from traditional side-chain resonance assignment and NOE assignment approaches in the following aspects. First, unlike most side-chain resonance assignment algorithms (Li & Sanctuary 1996, 1997, Pons & Delsuc 2001, Masse et al. 2006), NASCA does not require any input data from TOCSY experiments. Instead, it uses data from NOESY spectra, which also provide crucial distance restraints between protons and are normally required in high-resolution structure determination. Second, compared to other NOE assignment algorithms (Herrmann et al. 2002, Gronwald et al. 2002, Linge et al. 2003, Huang et al. 2006, Kuszewski et al. 2008, Zeng et al. 2009), which require a nearly complete set of both backbone and side-chain resonance assignments, NASCA only requires the backbone chemical shift information (and NOESY data) as input. Third, traditional approaches (Herrmann et al. 2002, Gronwald et al. 2002, Linge et al. 2003, Huang et al. 2006, Kuszewski et al. 2008) usually use a partial set of assigned NOEs to generate the initial structure templates for bootstrapping the NOE assignment, while NASCA exploits the RDC-defined initial backbone fold in an MRF framework to filter ambiguous NOE assignments. Since we do not rely heavily on the NOESY data to define the global fold, NASCA to some extent avoids the circularity that NOEs are used to define the fold, but the fold is needed in the NOE assignment. Fourth, traditional approaches (Herrmann et al. 2002, Gronwald et al. 2002, Linge et al. 2003, Huang et al. 2006, Kuszewski et al. 2008) rely on heuristic techniques, such as molecular dynamics (MD) or simulated annealing (SA), to compute structure templates for filtering ambiguous NOE assignments. Such MD/SA-based heuristic approaches can be trapped into local minima and might miss the global minimum solution. In contrast, the initial backbone fold used in NASCA is computed by systematically searching for the global optimal solution over all backbone dihedral angle roots, which are obtained by exactly solving a system of quartic RDC equations (Wang & Donald 2004, Zeng et al. 2009, Donald & Martin 2009). Fifth, unlike other Bayesian approaches (Lemak et al. 2008, 2011) or probabilistic graphical models (Bahrami et al. 2009) used in NMR resonance assignment, which mainly depend on Monte Carlo (MC) stochastic search or belief propagation algorithms to compute resonance assignments and therefore can be trapped into local minima, NASCA employs deterministic DEE/A* search algorithms that guarantee to find the global optimum.

To empirically investigate whether traditional SA/MD-based structure determination protocols are able to converge to a good backbone structure using sparse data, we ran XPLOR-NIH for ubiquitin, hSRI and FF2 on the same data that we used in computing the initial fold at medium resolution (Sec. 2.3). These data include RDCs, sparse NOEs extracted from the NOESY data to pack SSEs, and dihedral angle restraints derived from TALOS (Cornilescu et al. 1999). Table 4 summarizes the sparse data that were used by RDC-ANALYTIC to compute the packed SSE structure regions for proteins ubiquitin, hSRI and FF2. In the XPLOR-NIH structure calculation, a standard simulated annealing protocol was used to compute an ensemble of initial structures and then a water-refinement protocol with the RDC data was used to refine these structures. The second step is also called the RDC refinement step. In total we computed 100 structures, and selected the top 20 structures with the lowest energies as the ensemble of final structures for examination. In particular, we examined whether the SA/MD protocol in XPLOR-NIH was able to determine the same accurate core structures (i.e., SSE backbones) as we computed using our backbone determination techniques (Wang & Donald 2004, Zeng et al. 2009, Donald & Martin 2009), using the same sparse data (Table 4). Our tests show that although XPLOR-NIH was able to compute an ensemble of core structures for ubiquitin that were reasonably close to the NMR reference structure (with backbone RMSD 1.7 Å for the mean coordinates), it failed to converge to a good structure ensemble for both hSRI and FF2. For hSRI, the ensemble of structures computed by XPLOR-NIH had both high energy score and large RMSD to the NMR reference structure (Fig. 7A). The backbone RMSD between the mean coordinates (in the SSE regions) of the computed structures and the NMR reference structure was 7.3 Å. For FF2, the structures after the RDC refinement seemed sensitive to the chosen starting structures calculated from the standard simulated annealing protocol. Fig. 7B and Fig. 7C show the plots of energy vs. backbone RMSD to the NMR reference structure for two different starting structures, which had the lowest energies and represented the converged structure clusters computed in the initial simulated annealing step. For both cases, XPLOR-NIH failed to compute a decent structure ensemble using the sparse data in Table 4. The backbone RMSD between the mean structure and the NMR reference structure in the SSE regions was 5.7 Å and 6.9 Å for Fig. 7B and Fig. 7C respectively. In Fig. 7B, although there were two good structures with backbone RMSD less than 2.0 Å from the reference structure, we cannot identify them from others using current available criteria, such as the energy score or the number of violations. All these results indicate that traditional SA/MD protocol cannot guarantee to converge to a reliable structure when using the sparse data (Table 4). On the other hand, as we showed in the Results Section and in (Zeng et al. 2009), our backbone structure determination approach using the analytic solutions to the RDC equations is able to compute the core structure of the protein to medium resolution. The initial fold computed by our approach was successfully used to resolve the assignment ambiguity and bootstrap the high-resolution structure determination. Note that here we are not claiming XPLOR-NIH cannot converge when using a dense set of data restraints. Instead, we argue that when the sparse data (e.g., Table 4) are used, our approach is more robust and can compute a more reliable initial fold for high resolution structure determination over traditional SA/MD-based methods.

While traditional SA/MD protocols may be inadequate to bootstrap the initial global fold when using only sparse data (Table 4), RDC-ANALYTIC could do this robustly. However, other strategies might be possible. In principle, modeling approaches, such as protein structure prediction (Baker & Sali 2001), protein threading (Xu et al. 1998) or homology modeling (Langmead & Donald 2003, 2004b), could be used to compute the global fold. However, these modeling approaches can be heavily dependent on existing structural motifs available in the current databases.

By using backbone chemical shift information, CS-ROSETTA (Shen et al. 2008) could also be used to compute the initial global fold. CS-ROSETTA combines the empirical relationship between structures and chemical shifts with structure prediction techniques (Baker & Sali 2001) to generate protein structures. Recently, CS-ROSETTA has been extended to use additional backbone data, such as RDCs, and NOEs between amide protons, to determine the structures of several larger proteins, varying in size from 62 to 266 residues (Raman et al. 2010). We envision that, in addition to backbone data, side-chain/backbone and side-chain/side-chain NOE distance restraints will still be required to determine high-resolution structures of large proteins, and the NOEs will be particularly important for determining the side-chain conformations.

In (Fiorito et al. 2008), the authors proposed an algorithm, called ASCAN, that uses the knowledge of local covalent polypeptide structures to iteratively assign side-chain resonances from previously-assigned resonances (initially, backbone resonances were assigned) using NOESY or TOCSY spectra. Compared to ASCAN (Fiorito et al. 2008), in which only the conformation-independent bounds on intra-residue and sequential inter-proton distances are used to iteratively assign side-chain resonances, NASCA applies an MRF that leverages the RDC-defined backbone conformations to derive side-chain resonance assignments and NOE assignments. The main differences between ASCAN and NASCA lie in the following aspects. First, ASCAN only performs side-chain resonance assignment from NOESY or TOCSY data, and still needs to depend on other SA/MD-based programs such as CANDID (Herrmann et al. 2002) to obtain the NOE assignments for protein structure calculation. On the other hand, NASCA computes both side-chain resonance assignments and NOE assignments. Second, in ASCAN, only local NOE distance information is used in resolving side-chain assignment ambiguity, while in NASCA, the RDC-defined global fold is incorporated into a sound MRF framework to filter ambiguous assignments. In principle, NASCA can better prevent the local minima and error propagation problem in the assignment process. Third, in ASCAN, side-chain resonances are assigned iteratively, and current resonance assignments are dependent on the correctness of side-chain resonance assignments in previous iterations, while in NASCA, a set of globally optimal assignments that best interpret the NMR data are computed. Fourth, in practice, NASCA seems to assign more side-chain resonances than ASCAN. As reported in (Fiorito et al. 2008), ASCAN can only assign the resonances of about 80% of protons, while NASCA can achieve the completeness of more than 90% for side-chain resonance assignment. Probably this is because NASCA uses more information (i.e., the RDC-defined backbone) in assigning side-chain resonances.

4.2 Limitations and Extensions

We offer the following guidelines on the required resolution R of the initial global fold input to NASCA. To estimate R, we determined the global fold of five proteins from RDC data plus sparse NOEs, as described in (Zeng et al. 2009; see Sec. 2.3) and the Results section. This resulted in packed SSE conformations and global folds with a range of RMSD to the reference structures, as described in Section 3. In every case, and for different RMSDs, NASCA was successful in assigning the side-chain resonances and NOEs. This allows us to estimate the range of acceptable resolutions, based on NASCA’s performance on the RDC-computed backbones. We thusly estimate the required accuracy of both the core structure (i.e., packed SSE conformations) and the entire backbone structure for the initial global fold. Specifically, we extrapolate that the initial global fold input to NASCA should contain a core structure with a backbone RMSD ≤ 1.85 Å and entire backbone structure with a backbone RMSD ≤ 2.0 Å from the ground truth structure.