Abstract

Manganese is a neurotoxin causing Manganism in individuals chronically exposed to elevated levels in their environment. Toxic manganese exposure causes mental and emotional disturbances, and a movement disorder similar to Idiopathic Parkinsons Disease. Manganese interferes with dopamine neurons involved in control of body movements. Recently, p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) is being used to alleviate symptoms of Manganism, but its mechanism of action is unknown. The eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, possesses a dopaminergic innervation of its gill. Oysters exposed to manganese have reduced levels of dopamine in the cerebral ganglia, visceral ganglia and gill, but not of norepinephrine, octopamine or serotonin. Those results are consistent with reported mechanisms of action of manganese in human and mammalian systems. In this study we determined the effects of PAS treatments on dopamine and serotonin levels in oysters exposed to manganese. Adult C. virginica were exposed to 500 µM and 1 mM of manganese with and without 500 µM and 1 mM of PAS by removing one shell and maintaining the animals in individual containers of aerated artificial sea water at 18° C for 3 days. Control animals were similarly treated without manganese or PAS. Dopamine and serotonin levels were measured by HPLC with fluorescence detection. PAS protected the ganglia and gill against the effects of 500 µM manganese, but not against the 1 mM manganese treatments. Serotonin levels were not affected by the treatments. The study demonstrates PAS can protect against reductions in dopamine levels caused by neurotoxic manganese exposure, but is concentration dependent. These findings may provide insights into the actions of PAS in therapeutic treatments of Manganism.

Introduction

Manganese is present in animal tissues and is required as an enzyme cofactor or activator for numerous reactions of metabolism1. While essential in trace amounts, excessive manganese exposure can result in toxic accumulations in human brain causing extrapyramidal symptoms similar to those seen in patients with Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease2–5, a dopaminergic cell disorder. This Parkinson-like neurological condition was first described in 1837 in two manganese ore-crushing mill workers6 and has since been referred to as Manganism7–10. Symptoms common to both disorders include gait imbalance, rigidity, tremors and bradykinesia7,11–13, suggesting a similar etiology of neuronal damage in the substantia nigra with a resulting deficiency of the neurotransmitter dopamine for the striatum. However, compared to Parkinsons disease, there are some differentiating features seen with Manganism including symmetry of effects, more prominent dystonia, a characteristic “cock walk,” an intention rather than resting tremor, earlier behavioral and cognitive dysfunction, difficulty turning, and a poor response to Levodopa2,14–20, suggesting different or more extensive damage in the basal ganglia or to the dopaminergic system.

The primary cause of manganese toxicity is believed to be by inhalation of manganese from the atmosphere21. In addition to mining and manganese ore processing, high levels of airborne manganese are possible in a number of other occupational settings, including welding, dry battery manufacture and use of certain organochemical fungicides like Maneb14, 22–25.

Although manganese toxicity has been recognized for some time, the primary mechanism underlying its neurotoxic effects remains elusive. Human and animal studies have shown that toxic exposure to manganese results in metal accumulations in various areas of the basal ganglia and dysfunction of cells of both the striatum and the globus pallidus2,26–32. Other studies have shown that manganese selectively targets dopaminergic neurons in the human basal ganglia14,31 and decreases dopamine levels in the striatum11,27,33–35. Considering the clinical similarities between Manganism and Parkinson’s Disease, and the fact that manganese accumulates in brain regions rich in dopaminergic neurons, it has long been suggested that the neurotoxicity caused by manganese involves a disruption in dopaminergic neurotransmission36–38.

Until recently, clinical interventions for Manganism have not been successful39. However in 2006, Jaing et al.39 reported the first effective treatment of Manganism. Treatments with the drug p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) reversed many of the symptoms of severe manganese intoxication in the patient. PAS is an anti-inflammatory drug which has been used to treat tuberculosis. They indicate that the exact mechanism of the drug action is unknown and that further studies of PAS in the treatment of manganese intoxication is necessary.

Bivalves and other marine invertebrates are often used in metal environmental toxicology studies because their tissues readily accumulate trace metals to concentrations that are usually much higher on a wet weight basis than what is present in the surrounding seawater40–42. Numerous reports have been made on the bioaccumulation of various heavy metals in the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, and other oyster species43–49. Dopamine, serotonin and other biogenic amines are present in the nervous tissue and gill of C. virginica50. The animal has a reciprocal dopaminergic and serotonergic innervation of the lateral ciliated cells of the gill, originating in the cerebral and visceral ganglia, which slow down and speed up the beating rates of the cilia, respectively51.

The animal is a simple system with which to study the relationships among biogenic amines, neurotoxins and other chemicals which may interact with them. Our lab reported that C. virginica incubated in MnCl2, readily accumulated manganese into its ganglia and tissues52 and caused a reduction in the levels of dopamine in the oyster’s cerebral ganglia, visceral ganglia and gill, while having no effects on levels of other biogenic amines, including serotonin, epinephrine and octopamine53. We also showed that manganese treatments impaired the animals dopaminergic innervation of the lateral ciliated cells of the gill, but did not impair the serotonin innervation54.

In the present study we sought to use C. virginica as a model to study the effects of PAS treatments on the effects of manganese on a known dopaminergically innervated system.

Materials and Methods

Oysters were maintained in Instant Ocean® artificial seawater (ASW) obtained from Aquarium Systems Inc. (Mentor, OH). Dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, epinephrine, octopamine and 1-octanesulfonic acid (sodium salt, SigmaUltra) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All other reagents including manganese chloride (MnCl2·4H2O, ASC grade) were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Adult C. virginica of approximately 80 mm shell length were obtained from Frank M. Flower and Sons Oyster Farm in Oyster Bay, NY. They were maintained in the lab for up to two weeks in temperature-regulated aquaria in ASW at 16 – 18° C, specific gravity of 1.024 ± 0.001, salinity of 31.9 ppt, and pH of 7.2 ± 0.2. Each animal was tested for health prior to experimentation by the resistance it offered to being opened. Animals that fully closed in response to tactile stimulation and required at least moderate hand pressure to being opened were used for the experiments. In order to ensure that each oyster would receive equal exposure to manganese during the experiment and not just close up, healthy specimens were shucked by removing their right shell before being placed into individual temperature-controlled aerated containers of ASW for 3 days in the presence of up to 1.0 mM of manganese and PAS. Control animals were similarly prepared without exposure to added manganese and PAS. Both control and experimentally treated animals tolerated the 3-day treatment well. Survival was excellent, there were no fatalities, and only animals with visible signs of heart pumping were used in subsequent experiments.

Endogenous serotonin and dopamine levels of the cerebral and visceral ganglia, as well as the gill were measured using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection based on the method of Fotopoulou and Ioannou55. Animals were treated for three days with or without manganese and PAS after which time each animal’s cerebral ganglia, visceral ganglia and gill were excised and prepared for HPLC measurements of amine levels. The dissected tissues were homogenized with a Brinkman Polytron homogenizer with Omni International disposable probe tips in 0.4 M HCl. They were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 minutes and then vacuum filtered through a 0.24 micron filter. Aliquots (20 µl) of the samples were injected into a Beckman System Gold 126/168 HPLC system fitted with a Phenomenex-Gemini (Torrance, CA) 5µ C18 reverse phase, ion pairing column with a guard column. The mobile phase was 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 4.7) containing 1-octanesulfonic acid (1.1 mM) and EDTA (0.11 mM), mixed with methanol (85:15 v/v). All reagents were HPLC grade. The flow rate was 2 ml/min in isocratic mode. A Jasco FP 2020 Plus Spectrofluorometer was used for detection of native fluorescence (280 nm excitation, 320 nm emission) and was fitted with a 16 µl flow cell. HPLC results are reported as ng/g wet weight for gill and ng/ganglion for the ganglia. Statistical analysis comparing dopamine and serotonin levels in gill and ganglia of treated animals to the controls was determined by a Two-way ANOVA.

Results

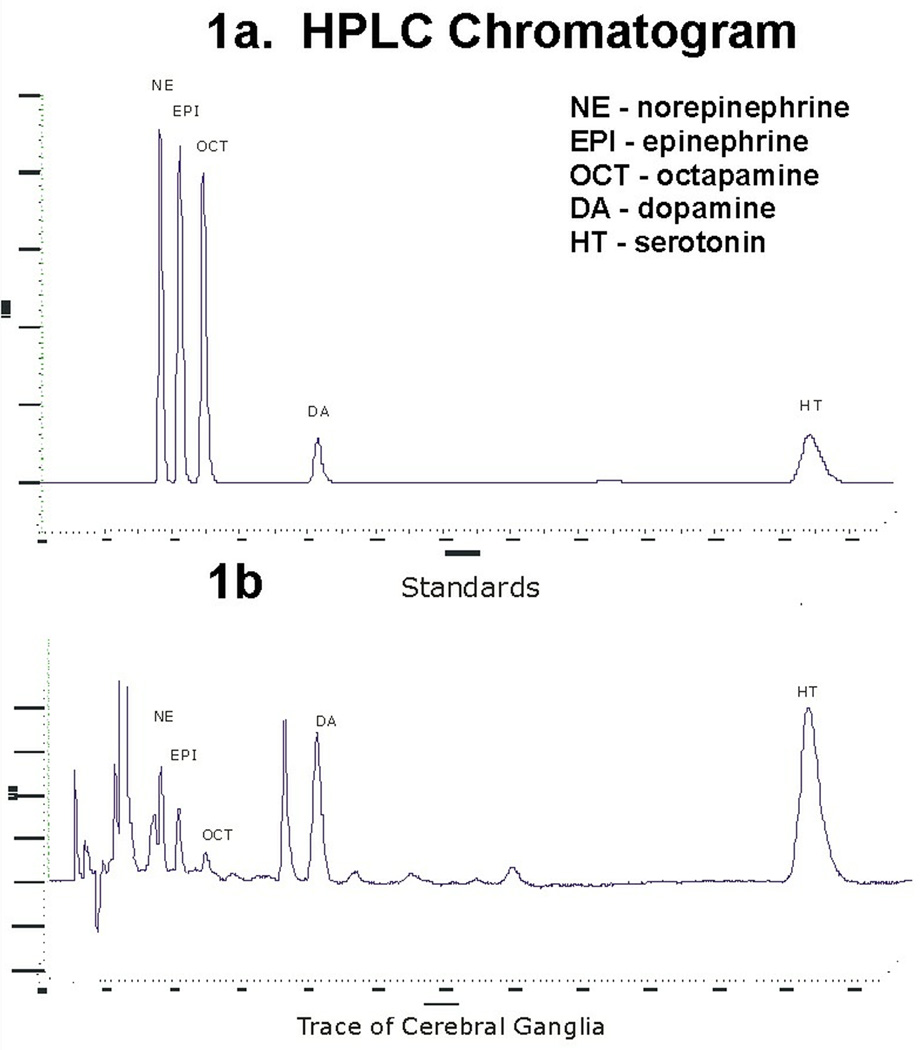

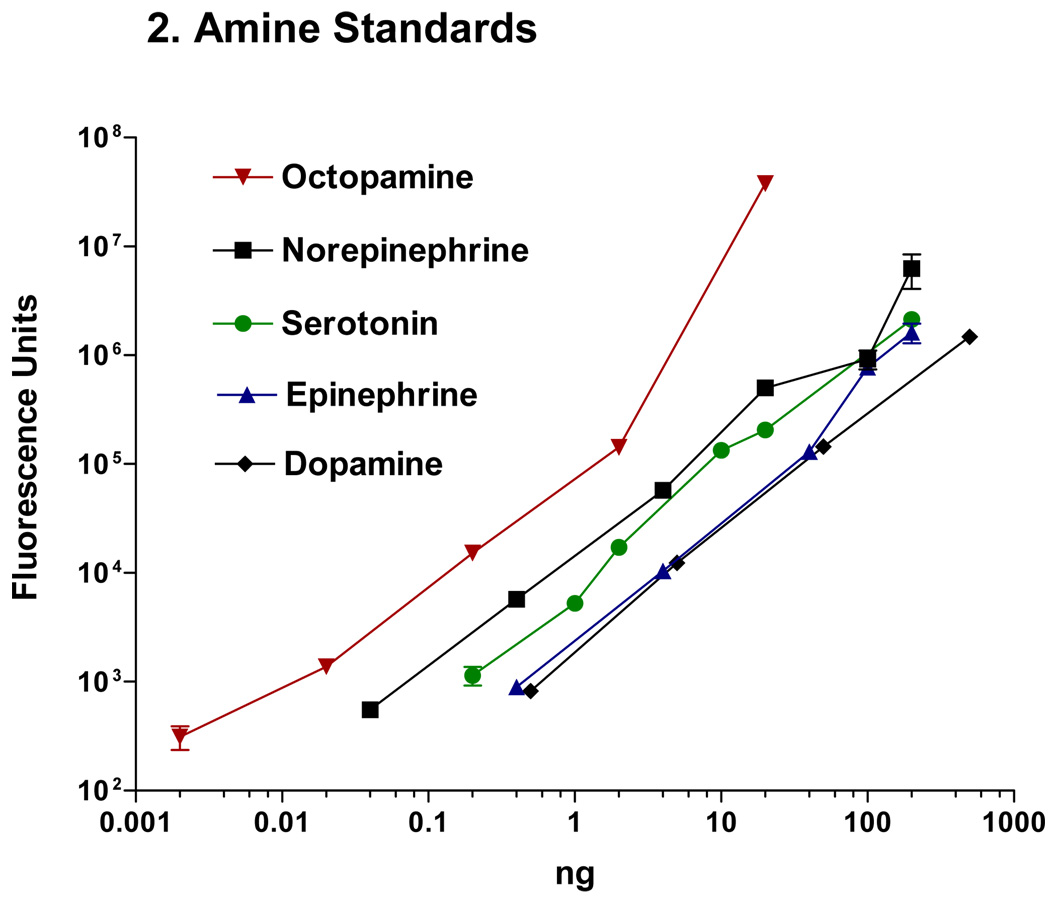

Serotonin and dopamine are able to be separated and quantified using HPLC with fluorescence detection. Chromatographs of the amine peaks for standards and a cerebral ganglion are shown in Figures 1a,b. The sensitivity is in the high picogram levels (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

a. Chromatogram of amine standards.

b. Chromatogram of cerebral ganglia

Figure 2.

Graph showing relative fluorescence of amine standards at excitation wavelength of 280 nm and emission wavelength of 320 nm.

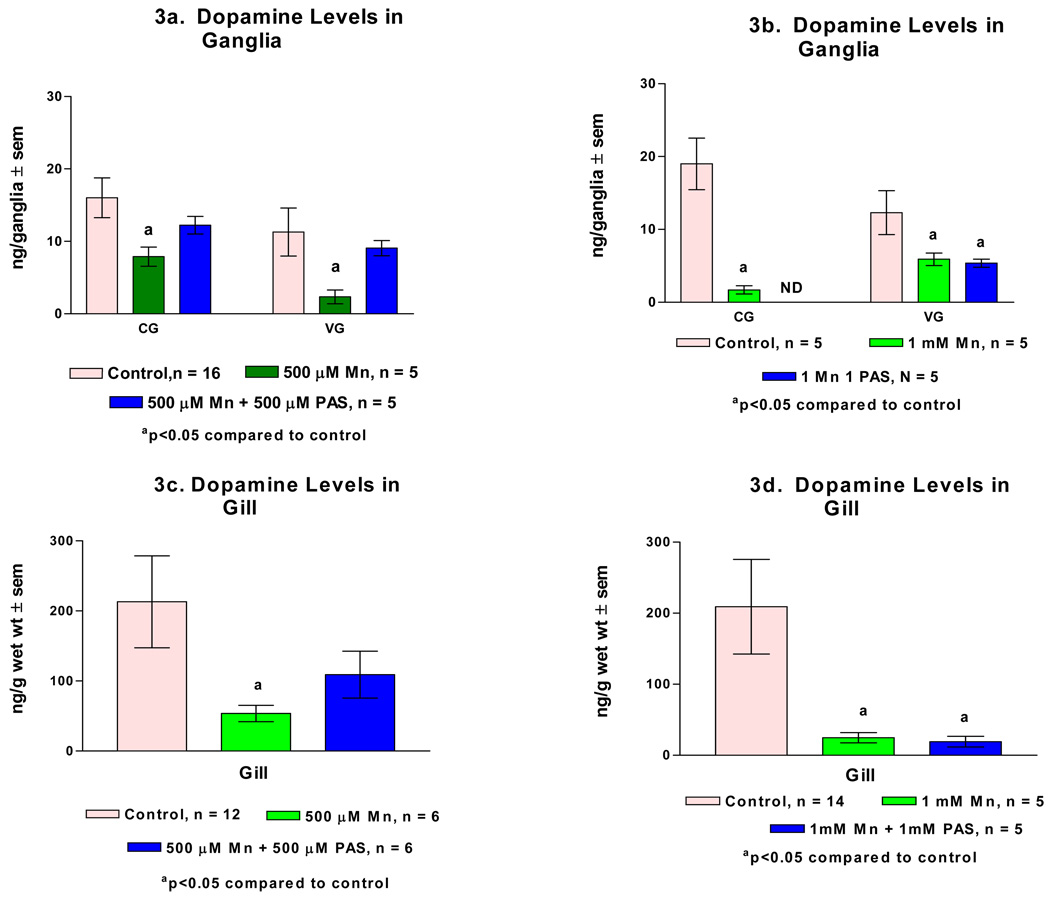

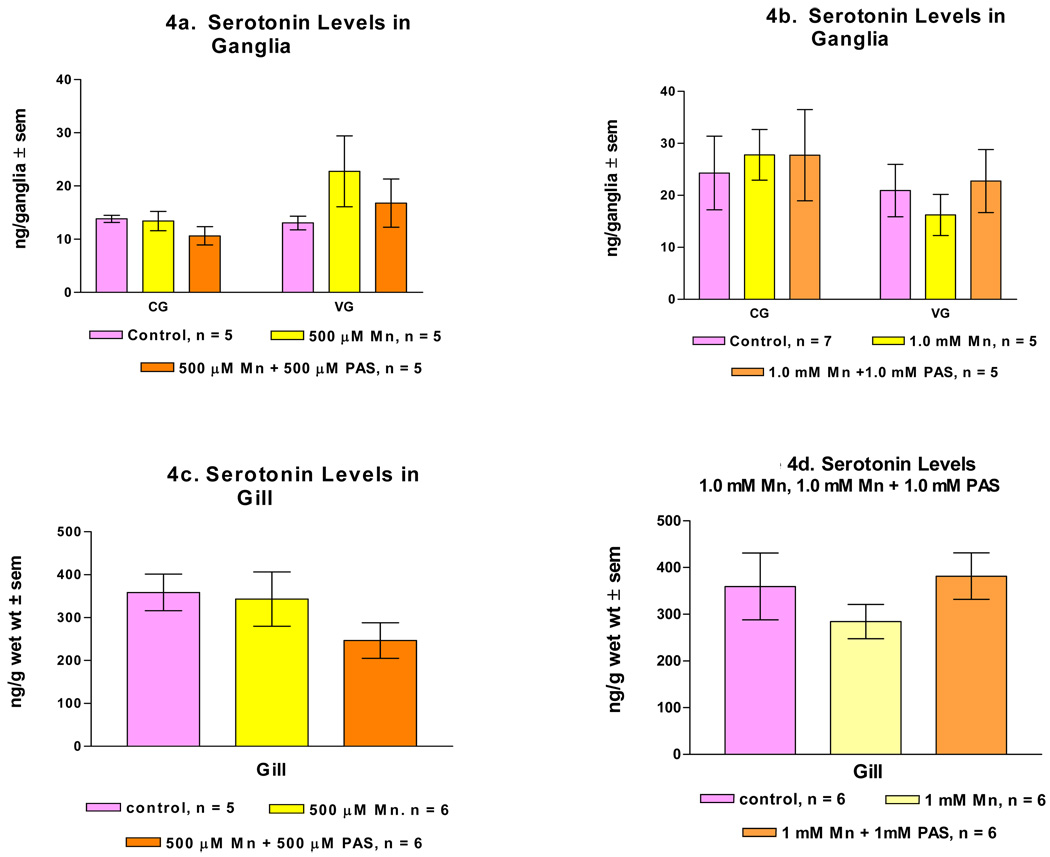

Endogenous dopamine levels in the cerebral and visceral ganglia of untreated animals are in the range of 20 ng/ganglion and 200 ng/g wet weight for the gill. Treating animals for 3 days with 500 µM and 1 mM of manganese significantly reduced dopamine levels in the ganglia and gills (Fig. 3). Serotonin levels were not significantly changed in any of the tissues as a result of either treatment (Fig. 4). The dopamine levels in the ganglia and gill of animals which were co-treated with manganese and PAS were not significantly reduced when 500 µM of PAS was administered with the 500 µM of manganese. However, when 1 mM of PAS was administered with 1 mM of manganese, the dopamine levels in the ganglia and gill were significantly reduced as compared to the untreated controls (Fig. 3). The treatment with manganese and PAS caused no changes in serotonin levels in the ganglia and gill (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

a. dopamine levels (ng/ganglion ± sem) in the cerebral (CG) and visceral ganglia (VG) of animals treated with 500 µM of manganese (Mn), and 500 µM of Mn and PAS (p-aminosalicylic acid). Figure 3b. dopamine levels CG and VG of animals treated with 1 mM of Mn, and 1 mM of Mn and PAS. Figure 3c. dopamine levels (ng/g wet weight ± sem) in the gill of animals treated with 500 µM of Mn, and 500 µM of Mn and PAS. Figure 3d. dopamine levels in the gill of animals treated with 1 mM of Mn, and 1 mM of Mn and PAS. Statistical significance comparing treated animals to untreated controls was determined by a Two way ANOVA.

Figure 4.

a. serotonin levels in the CG and VG of animals treated with 500 µM of manganese (Mn), and 500 µM of Mn and PAS (p-aminosalicylic acid). Figure 4b. serotonin levels CG and VG of animals treated with 1 mM of Mn, and 1 mM of Mn and PAS. Figure 4c. serotonin levels (ng/g wet weight ± sem) in the gill of animals treated with 500 µM of Mn, and 500 µM of Mn and PAS. Figure 4d. serotonin levels in the gill of animals treated with 1 mM of Mn, and 1 mM of Mn and PAS. Statistical significance comparing treated animals to untreated controls was determined by a Two way ANOVA.

Discussion

An earlier study showed that a 3-day treatment of C. virginica with manganese disrupted the oyster’s dopaminergic, cilio-inhibitory mechanism, while not impairing the serotonergic cilio-excitatory mechanism54. The study also showed that manganese treatments lowered endogenous dopamine, but not serotonin levels, in the gill, cerebral ganglia and visceral ganglia of manganese-exposed animals compared to controls. Taken together, the results indicate the specificity of manganese toxicity on the animal’s dopaminergic system. The results of that study suggest that the observed physiological deficits resulting from manganese treatments could be due to several contributing factors, most likely a combination of effects involving reduced levels of neuronal dopamine, possible destruction or damage of dopamine neurons, reduction of terminally released dopamine, and impaired post-synaptic responses to terminally released of dopamine.

It the present study, manganese treatments decreased dopamine levels in the ganglia and gill, but not serotonin levels and PAS protected against the effects of the low dose of manganese on reducing dopamine levels in ganglia and gill.

Manganese is a trace element in animal systems required for normal carbohydrate, lipid, amino acid and protein metabolism, as well as a required cofactor for various antioxidant enzymes such as mitochondrial superoxide dismutase1,56. However when in excess, manganese is cytotoxic and has been shown to raise levels of reactive oxygen species57,58, deplete glutathione59, impair energy metabolism60,61, and cause oxidation of catecholamine and other biological chemicals62. The prooxidant character of excess manganese and the fact that metal accumulates in dopamine-rich areas of the brain strongly suggests that manganese toxicity is causing further oxidative stress on an already stressed dopaminergic system56,63–66.

While the cellular and molecular mechanism of manganese toxicity remains unclear, several lines of evidence suggest that exposure to manganese or manganese containing compounds induces oxidative stress-mediated dopaminergic cell death67–69 which is in agreement with current theories on oxidative stress as a mediator of neuronal death in Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases70–74.

Dopaminergic neurons and dopamine-rich areas of the brain are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress, because the enzymatic and non-enzymatic metabolism of dopamine can generate reactive oxygen species and various neurotoxic catecholamine metabolites such as 6-hydroxydopamine73,75–78. In a related bivalve, Mytilus edulis, a previous study showed that treatments with 6-hydroxydopamine caused a reduction in the animal’s ganglionic levels of dopamine79. A recent study using transgenic mice provided in vivo evidence that chronic exposure to unregulated cytosolic dopamine alone was sufficient to cause neurodegeneration in striatal neurons and resulting motor dysfunction80.

Jiang et al.39 speculated that the mechanism of action of PAS in alleviating Manganism may be due to a chelating ability of PAS or that the salicylic acid moiety in PAS, which possesses an antiinflammatory effect, may contribute to therapeutic effectiveness of PAS in treatment of neurodegenerative Manganism. Other studies have suggested that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including sodium salicylic acid, may have neuroprotective benefit, because the inflammatory processes have been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis81,82.

The present study demonstrates that the gill and ganglia preparations of C. virginica can be used to investigate mechanisms that underlie manganese neurotoxcity, and may also serve as a model in the pharmacological study of drugs to treat or prevent Manganism and perhaps other dopaminergic cell disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants 2R25GM06003-05 of the Bridge Program of NIGMS, 0516041071 of NYSDOE and 66273-0035, 0622197 of the DUE Program of NSF, 0420359 of the MRI Program of NSF and 66288-0035 of PSC-CUNY.

References

- 1.Cotzias GC. Manganese in health and disease. Physiological Reviews. 1958;38:503–532. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1958.38.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calne DB, Chu NS, Huang CC, Lu CS, Olanow W. Manganism and idiopathic Parkinsonism: similarities and difference. Neurology. 1994;44:1583–1586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.9.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aschner M. Manganese in health and disease: from transport to neurotoxicity. In: Massaro E, editor. Handbook of Neurotoxicology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy BS, Nassetta WJ. Neurological effects of manganese in humans: a review. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2003;9:153–163. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2003.9.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobson AW, Erikson KM, Aschner M. Manganese neurotoxicity. Annal of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1012:115–128. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couper J. On the effects of black oxide of manganese when inhaled into the lungs. British Annals of Medical Pharmacology. 1837;1:41–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mena I, Marin O, Fuenzalida S, Cotzias GC. Chronic manganese poisoning. Clinical picture and manganese turnover. Neurology. 1967;17:128–136. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbeau A. Manganese and extrapyramidal disorders (a critical review and tribute to Dr. George C Cotzias) Neurotoxicology. 1984;5:13–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson J. The physiopathologic significance of manganese in brain: its relation to schizophrenia and neurodegenerative disorders. Neurotoxicology. 1987;8:451–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorell JM, Rybicki BA, Cole Johnson C, Peterson EL. Occupational metal exposures and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroepidemiology. 1999;18:303–308. doi: 10.1159/000026225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenstock HA, Simons DG, Meyer JS. Chronic manganism. Neurologic and laboratory studies during treatment with levodopa. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1971;217(10):1354–1358. doi: 10.1001/jama.217.10.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mena I, Court J, Fuenzalida S, Papavasiliou PS, Cotzias GS. Modification of chronic manganese poisoning. New England Journal of Medicine. 1970;282:5–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197001012820102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang CC, Chu NS, Lu CS, Wang JD, Tsai JL, Tzeng JL. Chronic manganese intoxication. Archives of Neurology. 1989;46(10):1104–1106. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460090018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olanow CW. Manganese-induced parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1012:209–223. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbeau A, Inoué N, Cloutier T. Role of manganese in dystonia. In: Eldridge R, Fahn S, editors. Advances in Neurology. vol 14. New York: Raven Press; 1976. pp. 339–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang CC, Lu CS, Chu NS, Hochberg F, Lilienfeld D, Olanow W. Progression after chronic manganese exposure. Neurology. 1993;43(8):1479–1483. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu CS, Huang CC, Chum NS, Calne DB. Levodopa failure in chronic manganism. Neurology. 1994;44(9):1600–1602. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.9.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koller WC, Lyons KE, Truly W. Effect of levodopa treatment for parkinsonism in welders. A double-blind study. Neurology. 2004;62:730–733. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113726.34734.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jankovic J. Searching for a relationship between manganese and welding and Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2005;64(12):2021–2028. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000166916.40902.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cersosimo MG, Koller WC. The diagnosis of manganese-induced parkinsonism. NeuroToxicology. 2006;27:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen ME, Gearhart JM, Clewell HJ., III Pharmacokinetic data needs to support risk assessments for inhaled and ingested manganese. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:161–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Academy of Sciences. Medical and biological effects of environmental pollutants: Manganese. Wash. DC: National Academy Press; 1973. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meco G, Bonfanti V, Vanacore N, Fabrizio E. Parkinsonism after chronic exposure to the fungicide maneb (manganese ethylene-bis-dithiocarbamate. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health. 1994;20:301–305. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reidy TJ, Bowler RM, Rauch SS, Pedroza GI. Pesticide exposure and neuropsychological impairment in migrant farm workers. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1992;7:85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iregren A. Manganese neurotoxicity in industrial exposures: proof of effects, critical exposure level, and sensitive tests. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erikson KM, Dobson AW, Dorman DC, Aschner M. Manganese exposure and induced oxidative stress in the rat brain. Science of The Total Environment. 2004;334–335:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eriksson H, Magiste K, Plantin LO, Fonnum F, Hedstrtm K, Theodorsson G, Norheim E, Kristensson K, Stalberg E, Heilbronn E. Effects of manganese oxide on monkeys as revealed by a combined neurochemical, histological and neurophysiological evaluation. Archives of Toxicology. 1987;61:46–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00324547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brenneman KA, Cattley RC, Ali SF, Dorman DC. Manganese induced developmental neurotoxicity in the CD rat: is oxidative damage a mechanism of action? Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:477–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagatomo S, Umehara F, Hanada K, Nobuhara Y, Takenaga S, Arimura K, Osame M. Manganese intoxication during total parenteral nutrition: report of two cases and review of the literature. Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1999;162:102–105. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newland MC. Animal models of manganese's neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:415–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pal PK, Samii A, Calne DB. Manganese neurotoxicity: a review of clinical features. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baek SY, Lee MJ, Jung HS, Kim HJ, Lee CR, Yoo C, Lee JH, Lee H, Yoon CS, Kim YH, Park J, Kim JW, Jeon BS, Kim Y. Effect of manganese exposure on MPTP neurotoxicities. Neurotoxicology. 2003;24:657–665. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parenti M, Flauto C, Parati E, Vescovi A, Groppetti A. Manganese neurotoxicity: effects of L-DOPA and pargyline treatments. Brain Research. 1986;367:8–13. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vescovi A, Facheris L, Zaffaroni A, Malanca G, Parati EA. Dopamine metabolism alterations in a manganese-treated pheochromocytoma cell line (PC12) Toxicology. 1991;67:129–142. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(91)90137-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sistrunk SC, Ross MK, Filipov NM. Direct effects of manganese compounds on dopamine and its metabolite DOPAC: An in vivo study. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2007;23:286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neff NH, Barrett RE, Costa E. Selective depletion of caudate nucleus dopamine and serotonin during chronic manganese dioxide administration to squirrel monkeys. Experientia. 1969;25:1140–1141. doi: 10.1007/BF01900234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hornykiewicz O. Dopamine and extrapyramidal motor function and dysfunction. Research Publications Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease. 1972;50:390–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham DG. Catecholamine toxicity: a proposal for the molecular pathogenesis of manganese neurotoxicity and Parkinson’s disease. NeuroToxicology. 1984;5:83–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang Y, Mo X, Du F, Fu X, Zhu X, Gao H, Xie J, Liao F, Pira E, Zheng W. Effective treatment of manganese-Induced occupational Parkinsonism with p-aminosalicylic acid: a case of 17-year follow-up study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006;48:644–649. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000204114.01893.3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rainbow PS. The significance of trace metal concentrations in marine invertebrates. In: Dallinger R, Rainbow PS, editors. Ecotoxicology of Metals in Invertebrates. Boca Raton, Florida: Lewis Publishers; 1993. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phillips D, Rainbow P. Biomonitoring of trace aquatic contaminants. London, New York: Elsevier Applied Science; 1993. p. 371. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boening DW. An evaluation of bivalves as biomonitors of heavy metal pollution in marine waters. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 1999;55:459–470. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capar SG, Yess NJ. US Food and Drug Administration survey of cadmium, lead and other elements in clams and oysters. Food Additives and Contaminants. 1996;13(5):553–560. doi: 10.1080/02652039609374440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bu-Olayan AH, Subrahmanyam MN. Accumulation of copper, nickel, lead and zinc by snail, Lunella coronatus and pearl oyster, Pinctada radiata from the Kuwait coast before and after the Gulf War oil spill. Science of the Total Environment. 1997;197(1):161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(97)05428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scanes PR, Roach AC. Determining natural background concentrations of trace metals in oysters from New South Wales. Australia Environmental Pollution. 1999;105(3):437–446. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abbe GR, Riedel GF, Sanders JG. Factors that influence the accumulation of copper and cadmium by transplanted eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) in the Patuxent River, Maryland. Marine Environmental Research. 2000;49(4):377–396. doi: 10.1016/s0141-1136(99)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang ZQ, Cheung RYH, Wong MH. Heavy Metal concentrations in edible bivalves and gastropods available in the major markets of the Pearl River Delta. Journal of Environmental Science. 2001;13(2):210–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spooner DR, Maher W, Otway N. Trace metal concentrations in sediments and oysters of Botany Bay, NSW, Australia. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2003;45(1):0092–0101. doi: 10.1007/s00244-002-0111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodney E, Herrera P, Luxama J, Boykin M, Crawford A, Carroll MA, Catapane EJ. Bioaccumulation and tissue distribution of arsenic, cadmium, copper and zinc in Crassostrea virginica grown at two different depths in Jamaica Bay, New York. In Vivo. 2007;29(1):16–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Downer N, Myrthil M, Nduka E, Lecky D, Catapane EJ. Effects of acute temperature stress on the distribution of biogenic amines in the American Oyster, Crassostrea virginica. Annals of the 2006 SICB Conference abstract P2.100.2006. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carroll MA, Catapane EJ. The nervous system control of lateral ciliary activity of the gill of the bivalve mollusc, Crassostrea virginica. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 2007;148A(2):445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murray S, Lovell A, Carroll MA, Catapane EJ. Distribution of manganese in the oyster Crassostrea virginica raised in Jamaica Bay, NY and its accumulations in oysters acutely exposed to high levels. Annals of the 2007 SICB Conference Abstract #2.19.2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lecky D, King C, Carroll MA, Catapane EJ. Neurotoxic effects of manganese on biogenic amines of the nervous system and innervated organs of Crassostrea virginica. Annals of the 2007 Society of Comparative and Integrative Biology Conference abstract #P3.80.2007. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin K, Huggins T, King C, Carroll MA, Catapane EJ. The neurotoxic effects of manganese on the dopaminergic innervation of the gill of the bivalve mollusc, Crassostrea virginica. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.05.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fotopoulou MA, Ioannou PCP. Post-column terbium complexation and sensitized fluorescence detection for the determination of norepinephrine, epinephrine and dopamine using high-performance liquid chromatography. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2002;462:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takeda A. Manganese action in brain function. Brain Research Reviews. 2003;41:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ali SF, Duhart HM, Newport GD, Lipe GW, Slikker Manganese-induced reactive oxygen species: Comparison between Mn+2 and Mn+3. Neurodegeneration. 1995;4:329–334. doi: 10.1016/1055-8330(95)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Milatovic D, Yin Z, Gupta RC, Sidoryk M, Albrecht J, Aschner JL, Aschner M. Manganese induces oxidative impairment in cultured rat astrocytes. Toxicological Sciences. 2007;98:198–205. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shi XL, Dalal NS. The glutathionyl radical formation in the reaction between manganese and glutathione and its neurotoxic implications. Med-Hypotheses. 1990;33(2):83–87. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(90)90184-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brouillet EPL, Shinobu U, McGarvey F, Hochberg F, Beal MF. Managnese injection into the rat striatum produces excitotoxic lesions by impairing energy metabolism. Experimental Neurology. 1993;120:89–94. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davis K, Saddler C, Carroll MA, Catapane EJ. Manganese disruption of mitochondrial respiration in the bivalve Crassostrea virginica and its protection by p-aminosalicylic acid. Annals of the 47th Conference of the Society of Toxicology Abstract # 1865.2008. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Archibald FS, Tyree C. Manganese poisoning and the attack of trivalent manganese upon catecholamines. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1987;256:638–650. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Galvani P, Fumagalli P, Santagostino A. Vulnerability of mitochondrial complex I in PC12 cells exposed to manganese. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;293:377–383. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(95)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sloot WN, Korf J, Koster JF, DeWit LEA, Gramsbergen JBP. Manganese-induced hydroxyl radical formation in rat striatum is not attenuated by dopamine depletion or iron chelation in vivo. Experimental Neurology. 1996;138:236–245. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aschner M. Metals and Oxidative Damage in Neurological Disorders. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. Manganese neurotoxicity and oxidative damage; pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 66.HaMai D, Bondy SC. Oxidative basis of manganese neurotoxicity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1012:129–141. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Wagner J, Kaul S, Kanthasamy AG. Caspase-3-dependent proteolytic cleavage of protein kinase C delta is essential for oxidative stress-mediated dopaminergic cell death after exposure to methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:1738–1751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01738.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stredrick DL, Stokes AH, Worst TJ, Freeman WH, Johnson EA, Lash LH, Aschner M, Vrana KE. Manganese-induced cytotoxicity in dopamine-producing cells. NeuroToxicology. 2004;25:543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Latchoumycandane C, Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Yang Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Protein kinase C delta is a key downstream mediator of manganese-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neuronal cells. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2005;313:46–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fahn S, Cohen G. The oxidant stress hypothesis in Parkinson's disease: evidence supporting it. Annals of Neurology. 1992;32:804–812. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Albers DS, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Neural Transmission Suppl. 2000;59:133–154. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6781-6_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulz JB, Lindenau J, Seyfried J, Dichgans J. Glutathione, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2000;267:4904–4911. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Molecular pathways of neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Science. 2003;302:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1087753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Emerit J, Edeas M, Bricaire F. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2004;58:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Halliwell B. Reactive oxygen species and the central nervous system. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1992;59 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10990.x. 1609-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lotharius J, Brundin P. Pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Dopamine, vesicles and alpha-synuclein. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2002;3:932–942. doi: 10.1038/nrn983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Shukitt-Hale B, Joseph JA. Dopamine neurotoxicity: age dependent behavioral and histological effects. Neurobiology of Aging. 2003;24:697–706. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stefano GB, Catapane EJ, Aiello E. Dopaminergic agents: Influence on serotonin in Molluscan nervous system. Science. 1976;194:539–541. doi: 10.1126/science.973139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen L, Ding Y, Cagniard B, Van Laar AD, Mortimer A, Chi W, Hastings TG, Kang UJ, Zhuang X. Unregulated cytosolic dopamine causes neurodegeneration associated with oxidative stress in mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:425–433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3602-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Asanuma M, Miyazaki I, Ogawa N. Neuroprotective effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on neurodegenerative diseases. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2004;10(6):695–700. doi: 10.2174/1381612043453072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, Haenggeli C, Huang YH, Bergles DE, Jin L, Hoberg MD, Vidensky S, Chung DS, Toan SV, Bruijn LI, Su Z, Gupta P, Fisher PB. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]