Abstract

The chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) is overexpressed in several cancers and metastases and as such presents an enticing target for molecular imaging of metastases and metastatic potential of the primary tumor. CXCR4-based imaging agents could also be useful for diagnosis, staging, and therapeutic monitoring. Here we evaluated a positron-emitting monocyclam analog, 64Cu-{N-[1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecanyl-1,4-phenylenebis(methylene)]-2-(aminomethyl)pyridine} (64Cu-AMD3465), in subcutaneous U87 brain tumors and U87 tumors stably expressing CXCR4 (U87-stb-CXCR4) and in colon tumors (HT-29) using dynamic and whole-body PET supported by ex vivo biodistribution studies. Both dynamic and whole-body PET/CT studies show specific accumulation of radioactivity in U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors, with the percentage injected dose per gram reaching a maximum of 102.70 ± 20.80 at 60 min and tumor-to-muscle ratios reaching a maximum of 362.56 ± 153.51 at 90 min after injection of the radiotracer. Similar specificity was also observed in the HT-29 colon tumor model. Treatment with AMD3465 inhibited uptake of radioactivity by the tumors in both models. Our results show that 64Cu-AMD3465 is capable of detecting lesions in a CXCR4-dependent fashion, with high target selectivity, and may offer a scaffold for the synthesis of clinically translatable agents.

Keywords: PET, tumor microenvironment, chemokine, stem cells, molecular imaging, colon cancer, brain cancer, metastasis

Compelling evidence demonstrates that chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) expression plays an important role in several diseases including HIV, cancer, and lupus (1–3). Although CXCR4 was discovered as a coreceptor for HIV-1 cell entry in the 1990s (4), recently much attention has been paid to investigating its role in cancer progression and metastasis. CXCR4 is overexpressed in more than 20 different human cancers (4,5); is required for tumor development, growth, vascularization, and metastases (5,6); and is considered a therapeutic target (7).

CXCR4 has been shown to be a prognostic factor in several cancers, including colorectal carcinoma (CRC). CXCR4 is differentially expressed in CRC and is required for the outgrowth of colon cancer metastasis (8,9). CXCR4 expression in primary CRC is associated with recurrence, poor survival, and liver metastasis (8). Most recently, in patients treated with the folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin regimen, enhanced CXCR4 expression was reported in resected liver metastases, suggesting that CXCR4 may be contributing to drug resistance and indicating an expanding role of CXCR4 in cancer biology (10).

In addition to the aforementioned biologic roles, several comprehensive studies have demonstrated that CXCR4 is necessary for cancer metastasis (11,12). Homing of cancer cells to the common destinations of cancer metastasis is mediated through the binding of CXCR4 to its cognate ligand, CXCL12, which is secreted in tissues that eventually harbor metastases (6,13). Extensive immunohistochemical studies have revealed that tumors with elevated CXCR4 expression often have an aggressive phenotype and that metastases often have elevated expression, compared with the primary tumor (14–16). Inhibition of CXCR4–CXCL12 signaling by antibodies, peptide analogs, small molecules, or small interfering RNA knockdown has demonstrated reduced metastatic burden in orthotopic and metastatic models of various cancers (11,12,17–22). Taken together, those preclinical and clinical observations demonstrate that CXCR4 plays a critical role in metastasis. In addition, the pleiotropic activity of CXCR4 and CXCL12 is critical for neural, vascular, and hematopoietic organogenesis, underscoring the need to stratify the patient population with high tumor CXCR4 levels. Accordingly, development of imaging agents that can noninvasively and repeatedly detect CXCR4 expression levels may prove useful in managing cancer patients. CXCR4-targeted imaging agents can be used to evaluate primary tumors for elevated CXCR4 expression and therapeutic intervention, to screen for secondary metastatic spread to both local and distant sites, and for therapeutic monitoring.

To image CXCR4 expression in tumor models, macro-molecular agents such as 111In- and 18F-labeled peptides and 125I-labeled monoclonal antibodies have been investigated using either SPECT/CT or PET (23–25). Others and our own group reported the imaging of CXCR4 expression using a low-molecular-weight agent, 64Cu-AMD3100, in control and tumor-bearing mice (26,27). Our studies with 64Cu-AMD3100 in human cancer xenografts showed clear detection of CXCR4 expression in an orthotopic breast cancer model and in experimental lung metastases. Though promising, the bicyclam AMD3100 has a relatively low affinity (~651 ± 37 nM) (28) and a structurally restricted scaffold. In search of agents that are amenable to structural modification, we pursued the monocyclam analog {N-[1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecanyl-1,4-phenylenebis(methylene)]-2-(aminomethyl)pyridine} (AMD3465) to image CXCR4 expression. Compared with AMD3100, AMD3465 has higher affinity, reduced size, and charge (29). The properties of AMD3465 as a CXCR4 inhibitor have been well characterized (30). AMD3465 is reported to have a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 41.7 ± 1.2 nM and 12.07 ± 2.02 nM for 125I-CXCL12 binding and calcium flux stimulated by stromal-derived factor-1α (29,30), respectively. Also, AMD3465 was shown to be 10-fold more effective as a CXCR4 antagonist than the bicyclam AMD3100 (31). Because of those favorable qualities, we examined the potential of AMD3465 as an imaging agent for CXCR4 expression. We used the ability of the cyclam to form strong complexes with copper to develop 64Cu-AMD3465 as an imaging agent for PET. Here, we report a detailed evaluation of 64Cu-AMD3465 in human subcutaneous brain tumor xenografts stably expressing CXCR4 by whole-body pseudodynamic imaging, whole-body static imaging, and ex vivo biodistribution studies. We also show the potential of 64Cu-AMD3465 to image graded levels of CXCR4 expression in a colon cancer model that has an intermediate level of CXCR4, compared with that found in the brain tumor model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

All cell culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen unless otherwise specified. The human glioblastoma cell line U87 and colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line HT-29 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and cultured in our laboratory in minimum essential medium and McCoy 5A medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units of penicillin per milliliter, and 100 mg of streptomycin per milliliter, respectively. A U87 cell line stably transfected with human CD4 and CXCR4 (U87-stb-CXCR4) was obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research Reference Reagent Program (32) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 1 μg of puromycin per milliliter, 300 μg of G418 per milliliter, 100 units of penicillin per milliliter, and 100 mg of streptomycin per milliliter. Cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Radiopharmaceutical Preparation

AMD3465 was a kind gift from Genzyme Corp., and 64Cu-CuCl2 was obtained from the University of Wisconsin. AMD3465 was radiolabeled with 64Cu-CuCl2 using a standard procedure, as described previously (26). Briefly, 200 μg of AMD3465·6HCl was added to 370–740 MBq (10–20 mCi) of 64Cu-CuCl2 concentrated in vacuo and adjusted to an approximate pH of 5–5.5 with 0.1 M sodium acetate, and the pH-adjusted reaction mixture was heated at 55–60°C for 45 min. 64Cu-AMD3465 was purified on a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography system (Varian) using a C-18 (Luna, 5 μm, 10 × 250 mm; Phenomenex) semipreparative column. A mobile phase with 15% MeOH (with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) and 85% H2O (with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) at a flow rate of 5 mL/min was used. 64Cu-AMD3465 was collected between 16 and 18 min, dried, and diluted in saline for cell and animal studies. Radioactive signal was detected using a single-channel radiation detector (model 105S; Bioscan) with ultraviolet absorbance monitored at 266 nm.

Determination of Partition Coefficient

The partition coefficient (log P) of 64Cu-AMD3465 complex was determined by adding 148–185 kBq (4–5 μCi) of the complex to a solution containing 1 mL of water and 1 mL of octanol (n = 3). The resulting solution was then shaken well for 1 h at room temperature. From each phase, 100-μL aliquots were (n = 3) counted separately. The partition coefficient was calculated as a ratio between counts in the octanol phase to counts in the water phase. An average log P value was obtained from those ratios.

Flow Cytometry

Surface CXCR4 expression levels were analyzed using a CXCR4 monoclonal antibody (clone 44716) conjugated to phycoerythrin (R&D Systems) according to procedures described previously (26).

Receptor Binding Assays

U87, U87-stb-CXCR4, and HT-29 cells seeded in 6-well plates at 60%–80% confluence were used for receptor binding assays. Cells were incubated with 37 kBq/mL (1 μCi/mL) of 64Cu-AMD3465 in phosphate-buffered saline binding buffer (containing 5 mM MgCl2,1 mM CaCl2, 0.25% bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4) for 30 min at 4°C. After incubation, cells were washed quickly 4 times with 4°C binding buffer, trypsinized using nonenzymatic buffer, and cell-associated activity was determined in a γ-spectrometer (1282 Compugamma CS; Pharmacia/LKB Nuclear, Inc.).

For internalization assays, cells were detached using non-enzymatic buffer, and aliquots of 1 million cells per tube were incubated with 37 kBq (1 μCi) of 64Cu-AMD3465 per milliliter for various times up to 4 h at 4°C or 37°C in the phosphate-buffered saline binding buffer. Assuming minimal receptor endocytosis at 4°C, the internalization assay was performed only with cells incubated at 37°C. At 15-, 30-, 60-, and 240-min intervals, the medium was removed and cells were washed once with binding buffer followed by a mild acidic buffer (50 mM glycine, 150 mM NaCl [pH 3.0]) at 4°C for 5 min. Then the acidic buffer was collected, and cells were washed twice with binding buffer. Pooled washes (containing cell surface–bound 64Cu-AMD3465) and cell pellets (containing internalized 64Cu-AMD3465) were counted in an automated γ-counter along with the standards. All of the radioactivity values were converted into percentage of incubated dose (%ID) per million cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times. Data were fitted according to linear regression analysis using PRIZM software.

Animal Models

All experimental procedures using animals were conducted according to protocols approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee. Female nonobese diabetic (NOD)/severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice (age, 6–8 wk; weight, 25–30 g) were purchased from the Johns Hopkins Immune Compromised Animal Core. Mice were implanted subcutaneously with U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 cells (4 × 106 cells/100 μL) in the upper left and right flanks, respectively. Similarly, HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cells (4 × 106 cells/100 μL) were inoculated in the upper right flanks of the mice. Animals were used for biodistribution and PET/CT experiments when the tumor size reached 300–400 mm3.

PET/CT and Analysis

Dynamic and whole-body PET and CT images were acquired on an eXplore VISTA small-animal PET (GE Healthcare) and an X-SPECT small SPECT/CT system (Gamma Medica Ideas), respectively. For imaging studies, mice were induced with 3% and maintained under 1.5% isoflurane (v/v). Pseudodynamic imaging studies were performed on NOD/SCID mice bearing U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 brain tumors. After intravenous injection of 64Cu-AMD3465 (range, 9.0–9.6 MBq; mean, 9.4 MBq), changes in radiotracer accumulation were recorded over the whole body using an imaging sequence consisting of 16 frames for a total of 70 min with variable dwell times (2 × 60 s, 6 × 120 s, 4 × 240 s, and 4 × 600 s), as described previously (33). After dynamic imaging, whole-body PET images (2 bed positions, 15-min emission per bed position) were acquired at 1.5, 4, 8, and 24 h after injection of radiotracer. For binding specificity studies, a separate group of mice (n = 2) was subcutaneously administered with a blocking dose of AMD3465 (25 mg/kg) at 1 h before the injection of 64Cu-AMD3465, and another set of 2 mice was injected with 64Cu-CuCl2 alone. In colon cancer xenografts, whole-body images were acquired at 90 min after injection of 64Cu-AMD3465 alone or with a blocking dose. After each PET scan, a CT scan was acquired in 512 projections for anatomic coregistration. PET emission data were corrected for decay and dead time and reconstructed using the 3-dimensional ordered-subsets expectation maximization algorithm. Data were analyzed based on regions of interest drawn within the tumors or tissue. The percentage of injected dose per gram (%ID/g) was calculated based on a calibration factor that was determined using a known quantity of radioactivity. Time–activity curves were calculated as an average from the region-of-interest analyses of 4 mice. Data were analyzed using AMIDE software (SourceForge), and volume-rendered images were generated using Amira 5.2.0 software (Visage Imaging Inc.).

Ex Vivo Biodistribution

NOD/SCID mice harboring either brain or colon xenografts were injected intravenously with 740 kBq (20 μCi) of 64Cu-AMD3465 in 200 μL of saline. At 30, 60, 90, 240, and 600 min after injection, animals were sacrificed; blood, tumors, and selected tissues were harvested and weighed; and the radioactivity in the tissues was measured in an automated γ-spectrometer. In the case of colon cancer xenografts, biodistribution studies were performed at 90 min after 64Cu-AMD3465 injection.

To demonstrate the in vivo specificity of 64Cu-AMD3465, a set of mice received a blocking dose of AMD3465 (25 mg/kg) subcutaneously at 1 h before the injection of radiotracer, and another set of mice received 64Cu-CuCl2 alone. At 90 min after injection of radiotracers, ex vivo biodistribution studies were performed. Aliquots of the injected dose were counted as reference standards for the calculation of %ID/g values. A minimum of 4 animals per time point was used.

Immunohistochemistry

HT-29 tumors from biodistribution experiments were used for histologic examination. Sections of tumors were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and immunohistochemistry was performed on tumor tissues as previously described using rabbit polyclonal antibodies that recognize amino acids 328–338 of human CXCR4 (34), with minimum cross-reactivity to mouse CXCR4 (Imgenex) (26).

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using PRIZM software. An unpaired 2 tailed t test was used, and P values less than 0.05 for the comparison between tumors expressing high and tumors expressing low CXCR4 uptake were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Radiolabeling and Partition Coefficient

Radio–high-performance liquid chromatography assessment showed the radiochemical purity of 64Cu-AMD3465 to be greater than 98% (Supplemental Fig. 1; supplemental materials are available online only at http://jnm.snmjournals.org), with specific radioactivity in the range of 6.0 ± 3.1 GBq/μmol (162 ± 84 mCi/μmol). The log P value for the complex was −2.71 ± 0.37.

Receptor Expression, In Vitro Radioligand Binding, and Internalization

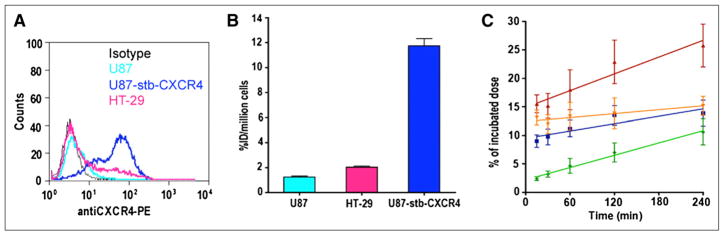

Flow cytometric analysis using CXCR4 antibody (clone 44716) revealed that 2%, 95%, and 30% of U87, U87-stb-CXCR4, and HT-29 cells, respectively, were positive for CXCR4 (Fig. 1A). The radioligand binding studies, supported by these data, show a gradual increase in the accumulation of radioactivity on the order of U87-stb-CXCR4 > HT-29 > U87 (Fig. 1B). The internalization assays were done retrospectively to understand the retained radioactivity uptake observed in the U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors. Over the 4-h incubation period, a continuous accumulation of radioactivity was observed in cells incubated at 37°C, with slopes of 0.0360 ± 0.0022 and 0.0492 ± 0.0081 for internalized and total fractions, respectively. For cells incubated at 4°C, a lower slope of 0.0215 ± 0.0060 was observed (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

In vitro characterization of CXCR4 expression. (A) Evaluation of surface CXCR4 expression in cancer cell lines used by flow cytometry. (B) Uptake analysis of 64Cu-AMD3465 in cancer cell lines. (C) Internalization of CXCR4 in U87-stb-CXCR4 cells: 4°C (green), 37°C total (red), 37°C cell surface (orange), and 37°C internalized (blue).

PET

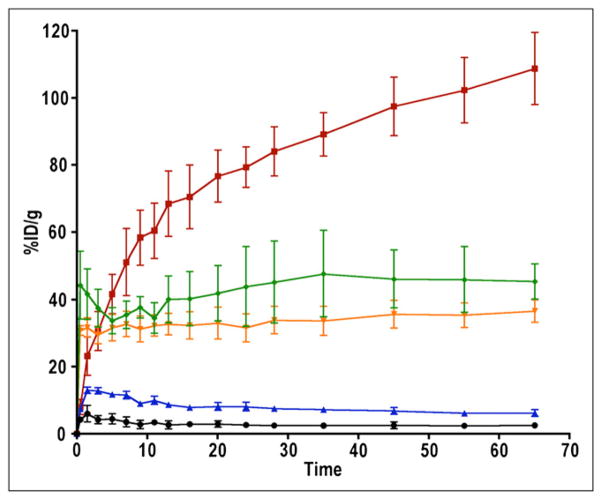

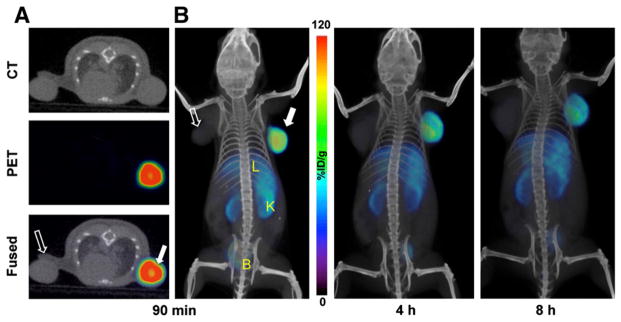

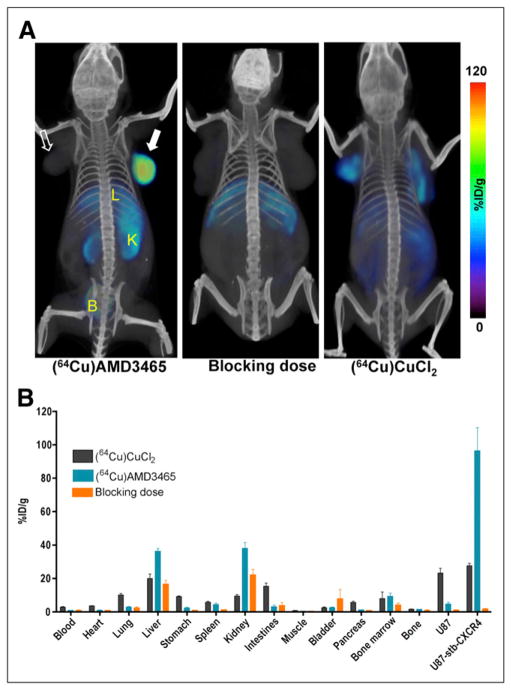

The time–activity curves acquired in mice harboring U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 subcutaneous brain tumor xenografts over 70 min showed continuous 64Cu-AMD3465 uptake in U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors (Fig. 2). The %ID/g for U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors reached up to 110 at 65 min (Fig. 2). The %ID/g values for U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors at 65 min were nearly 3-fold greater than those of kidneys and liver and nearly 18-fold greater than for the U87 tumors. The whole-body PET/CT images acquired on U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 brain xenografts at different times are shown in Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure 2. The highest signal intensity was observed in the U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors at all time points. The best image contrast for U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors was noticed at 90 min after injection. Even after two 64Cu half-lives and 24 h after injection of the radiotracer, U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors were clearly visible. Other organs with noticeable uptake were the liver and kidneys. On the basis of these image contrast data, in vivo specificity studies and imaging studies in the colon tumor model were performed at 90 min after injection of tracers. A 25 mg/kg blocking dose of AMD3465 resulted in a significant reduction of 64Cu-AMD3465 uptake in U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors, demonstrating the specificity of the radiotracer (Fig. 4A). Further evidence of specificity was established by uniform uptake observed in mice injected with only 64Cu-CuCl2 (Fig. 4A). PET studies of mice with HT-29 tumors showed specific accumulation of activity in the tumors (Fig. 5A). Also, the blocking dose inhibited the radioactivity uptake in tumors, further demonstrating the 64Cu-AMD3465 specificity in these tumor models (Fig. 5A). Supporting the CXCR4 expression levels observed in vitro, the uptake of 64Cu-AMD3465 in HT-29 tumors was intermediate between that of U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors.

FIGURE 2.

Dynamic imaging of CXCR4 expression in subcutaneous U87 xenografts with 64Cu-AMD3465. NOD/SCID mice bearing U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 glioblastoma xenografts on left and right flanks, respectively, were given approximately 9.25 MBq (250 μCi) of 64Cu-AMD3465 via tail vein injection, and whole-body pseudodynamic imaging was performed for 70 min. Dynamic time–activity curves are for various tissues: muscle (black), U87 (blue), kidney (orange), liver (green), and U87-stb-CXCR4 (red). Data are mean ± SD of 4 animals. Specific accumulation of radioactivity in U87-stb-CXCR4 (red line) over U87 (blue line) is apparent.

FIGURE 3.

PET/CT images of CXCR4 expression in subcutaneous brain tumor xenografts with 64Cu-AMD3465. NOD/SCID mice bearing U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 glioblastoma xenografts on left and right flanks, respectively, were given approximately 9.25 MBq (250 μCi) of 64Cu-labeled radiotracers via tail vein injection, and PET/CT images were acquired. (A) Representative trans-axial PET, CT, and fused sections of both tumors from a mouse injected with 64Cu-AMD3465 at 90 min after injection. (B) Representative volume-rendered whole-body images of a 64Cu-AMD3465 injected mouse at 90 min (left), 4 h (middle), and 8 h (right) after injection. All images were decay-corrected and scaled to same maximum threshold value. B = bladder; K = kidney; L = liver; solid arrow = U87-stb-CXCR4 tumor; unfilled arrow = U87 tumor.

FIGURE 4.

In vivo specificity of 64Cu-AMD3465 in subcutaneous brain tumor xenografts. NOD/SCID mice bearing U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 glioblastoma xenografts on left and right flanks, respectively, were given approximately 9.25 MBq (250 μCi) of 64Cu-labeled radiotracers via tail vein injection, and PET/CT images were acquired. (A) Representative volume-rendered whole-body images of 64Cu-AMD3465, AMD3465 blocking dose (25 mg/kg) followed by 64Cu-AMD3465, and 64Cu-CuCl2 alone. All images were scaled to same maximum threshold value. (B) Biodistribution analysis of selected tissues from mice injected with 740 kBq (20 μCi) of radiotracers and sacrificed at 90 min after injection. All radioactivity values were converted into %ID/g. Biodistribution data are mean ± SD of 4–5 animals. B = bladder; K = kidney; L = liver; solid arrow = U87-stb-CXCR4 tumor; unfilled arrow = U87 tumor.

FIGURE 5.

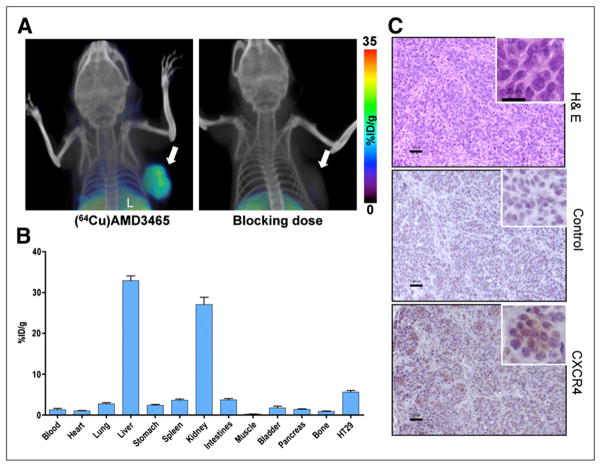

CXCR4 expression imaging in colon cancer xenografts with 64Cu-AMD3465. NOD/SCID mice harboring HT-29 colon cancer xenografts in upper right flank received either approximately 9.25 MBq (250 μCi) of 64Cu-AMD3465 or AMD3465 (25 mg/kg) blocking dose followed by 64Cu-AMD3465 via tail vein injection, and whole-body images were acquired at 90 min after injection. (A) Representative volume-rendered whole-body images showing clear and specific accumulation of radioactivity in HT-29 tumors. (B) Biodistribution analysis of selected tissues from mice injected with 740 kBq (20 μCi) of 64Cu-AMD3465 and sacrificed at 90 min after injection. All radioactivity values were converted into %ID/g. Biodistribution data are mean ± SD of 6 animals. (C) Representative microscopy images of 10-μm-thick sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin and CXCR4 obtained at ×10 magnification from HT-29 tumors. A ×20 magnification is also shown in boxed region. H & E = hematoxylin and eosin; L = liver; solid arrow = HT-29 tumor.

Ex Vivo Biodistribution

To validate the imaging studies and further quantify the 64Cu-AMD3465 uptake, biodistribution studies were performed at 30, 60, 90, 240, and 600 min in the brain tumor model (Table 1). Those biodistribution studies showed the highest uptake in the U87-stb-CXCR4 tumor at all time points. Other tissues with noticeable uptake were the liver, kidneys, and bone marrow. All other tissues had a low %ID/g, in agreement with PET data. The tumor-to-muscle and tumor-to-blood ratios for both tumors are shown in Table 2 and support the best contrast observed in PET/CT at 90 min after injection. The blocking dose of AMD3465 resulted in a greater than 95% reduction in the tumor uptake of radioactivity (Fig. 4B). The %ID/g for the kidneys, liver, spleen, and bone marrow reduced roughly by half, suggesting that a significant portion of that uptake was CXCR4-mediated. In mice injected with 740 kBq (20 μCi) of 64Cu-CuCl2, relatively low but uniform distribution of radioactivity was observed in several tissues and both tumors.

TABLE 1.

64Cu-AMD3465 Ex Vivo Biodistribution Studies for Subcutaneous Brain Tumor Xenografts

| Organ/tissue | Time (min) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 60 | 90 | 240 | 600 | |

| Blood | 1.93 ± 0.30 | 0.90 ± 0.08 | 0.73 ± 0.23 | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 1.20 ± 0.36 |

| Heart | 1.19 ± 0.16 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 0.90 ± 0.25 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.07 |

| Lung | 4.48 ± 0.56 | 3.70 ± 0.99 | 2.78 ± 0.47 | 3.39 ± 0.85 | 2.10 ± 0.13 |

| Liver | 32.08 ± 2.03 | 35.06 ± 7.77 | 36.15 ± 1.79 | 33.65 ± 3.13 | 27.27 ± 2.57 |

| Stomach | 1.91 ± 0.31 | 2.02 ± 0.76 | 2.17 ± 0.65 | 1.98 ± 0.102 | 1.21 ± 0.03 |

| Spleen | 6.23 ± 1.17 | 5.68 ± 1.75 | 4.28 ± 1.00 | 4.88 ± 0.42 | 2.64 ± 0.12 |

| Kidney | 32.45 ± 2.33 | 32.05 ± 4.03 | 37.93 ± 3.57 | 33.57 ± 6.39 | 25.15 ± 3.29 |

| Small intestines | 3.12 ± 0.53 | 3.33 ± 0.87 | 2.99 ± 1.01 | 2.77 ± 0.69 | 1.79 ± 0.19 |

| Muscle | 0.75 ± 0.52 | 0.37 ± 0.12 | 0.30 ± 0.13 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.02 |

| Bladder | 2.65 ± 0.32 | 4.75 ± 3.43 | 2.41 ± 0.51 | 2.17 ± 0.71 | 0.96 ± 0.21 |

| Pancreas | 1.19 ± 0.18 | 1.53 ± 0.32 | 1.13 ± 0.22 | 1.47 ± 0.62 | 0.68 ± 0.05 |

| Bone | 2.79 ± 0.74 | 1.53 ± 0.44 | 1.38 ± 0.19 | 1.12 ± 0.19 | 0.80 ± 0.36 |

| Bone marrow | 6.39 ± 0.00 | 10.22 ± 4.97 | 9.18 ± 2.04 | 8.10 ± 3.38 | 9.42 ± 3.88 |

| U87 | 3.34 ± 0.59 | 2.56 ± 0.20 | 4.15 ± 0.94 | 4.23 ± 1.30 | 4.03 ± 0.94 |

| U87-stb-CXCR4 | 106.58 ± 5.99* | 102.70 ± 20.80* | 96.29 ± 13.98* | 50.95 ± 6.38* | 28.92 ± 2.65* |

P < 0.0001, and comparative reference is U87 tumor uptake.

TABLE 2.

Tumor-to-Tissue Ratios for 64Cu-AMD3465 for Subcutaneous Brain Tumor Xenografts

| Ratio | Time (min) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 60 | 90 | 240 | 600 | |

| U87-stb-CXCR4 to U87 | 32.57 ± 5.51 | 40.19 ± 7.53 | 21.62 ± 4.36 | 12.85 ± 4.03 | 5.38 ± 2.97 |

| U87-stb-CXCR4 to muscle | 193.82 ± 108.55 | 297.78 ± 93.83 | 362.56 ± 153.51 | 222.95 ± 27.62 | 151.00 ± 29.91 |

| U87 to muscle | 5.88 ± 2.93 | 7.31 ± 1.59 | 17.53 ± 7.64 | 18.91 ± 7.25 | 42.04 ± 35.98 |

| U87-stb-CXCR4 to blood | 56.10 ± 7.93 | 114.76 ± 23.09 | 138.78 ± 30.87 | 83.47 ± 4.63 | 27.80 ± 9.93 |

| U87 to blood | 1.73 ± 0.09 | 2.85 ± 0.10 | 6.41 ± 0.63 | 6.97 ± 2.01 | 10.04 ± 2.95 |

Biodistribution studies in mice bearing HT-29 colon tumors were performed at 90 min after injection (Fig. 5B). The %ID/g for the HT-29 tumors was 5.62 ± 0.90, and the tumor-to-muscle and tumor-to-blood ratios were 24.78 ± 2.38 and 8.05 ± 0.60, respectively. No significant differences in radioactivity distribution were observed in other tissues, compared with the brain tumor model. Representative images of sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin or CXCR4 are shown in Figure 5C.

DISCUSSION

We investigated a radiolabeled version of a known high-affinity monocyclam inhibitor of CXCR4, AMD3465, as an imaging agent for CXCR4 expression. 64Cu-AMD3465 evaluation in U87 glioblastoma cells, U87 cells stably expressing CXCR4, and a colon tumor expressing intermediate levels of CXCR4 showed specific accumulation of radioactivity. The specificity, target selectivity, and tumor-to-muscle ratios observed suggest that 64Cu-AMD3465, compared with other known agents such as AMD3100, is a superior agent for PET of CXCR4 expression and can delineate graded levels of CXCR4 expression in tumors.

To determine the pharmacokinetics and establish the specificity, we initially investigated 64Cu-AMD3465 in subcutaneous brain tumor models stably expressing CXCR4. In vitro binding studies showed specific binding of radioactivity to U87-stb-CXCR4 cells, compared with the parental U87 cells. Also, the in vivo dynamic and whole-body PET/CT studies clearly demonstrated selective accumulation of radioactivity in the U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors, starting as early as 5 min after injection of the radiotracer. The tumor-to-muscle ratios reached a maximum at 90 min after injection of the radiotracer. The radioactivity uptake in liver and kidneys reached a maximum within few minutes after injection and remained constant up to 70 min. The radio-tracer accumulation in the U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors was evident even at 24 h. Retrospective in vitro analysis of 64Cu-AMD3465 uptake at 37°C in U87-stb-CXCR4 cells revealed that accumulation and retention of radioactivity was due to receptor-mediated endocytosis and perhaps binding of this radioactivity to cytosolic proteins. CXCR4-mediated endocytosis has been previously described using fluorescently labeled CXCL12 (35).

To validate further the utility of 64Cu-AMD3465, we pursued imaging and biodistribution studies in a colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line, HT-29, that has 30% of its cells expressing CXCR4 as determined by flow cytometry. Both PET and biodistribution studies showed clear and specific accumulation of radioactivity in tumors derived from those cells. This radioactivity uptake in tumors was significantly reduced in blocking studies, further validating the specificity of 64Cu-AMD3465. Furthermore, the %ID/g values of HT-29 tumors were intermediate to U87 and U87-stb-CXCR4 tumors, suggesting that variable levels of CXCR4 expression could be delineated using this imaging agent.

Previously, we investigated the bicyclam AMD3100 as a PET agent for CXCR4 expression in the same glioblastoma models, which allows for comparison between these 2 agents (26). The tumor-to-muscle and tumor-to-blood ratios for 64Cu-AMD3465 at 90 min after injection are 7- to 8-fold higher than those of 64Cu-AMD3100, suggesting the superiority of 64Cu-AMD3465 as an imaging agent. Even though 64Cu-AMD3465 has improved affinity and kinetics, compared with 64Cu-AMD3100, considerable uptake in the liver and kidneys was also observed. CXCR4 expression in the liver and kidneys has been reported (34,36), and reduced uptake has been observed in blocking studies in these tissues, suggesting that some of the uptake seen is receptor-mediated. Also, copper–cyclam complexes are reported to be thermodynamically stable; however, several in vitro studies have shown dissociation of copper from the complex (37,38). Therefore, some of this accumulation could be attributed to possible transchelation of 64Cu from 64Cu-AMD3465 to plasma proteins. Our previous studies with bicyclam 64Cu-AMD3100 have shown that copper bound in the cyclam is stable for at least 4 h after injection of the radiotracer. These previous reports, combined with the loss of binding observed in our blocking studies and rather uniform uptake of radioactivity seen in 64Cu-CuCl2-injected mice, suggest that the observed uptake is not related to transchelation but is receptor-mediated. Furthermore, the radioactivity in the blood of mice injected with 64Cu-AMD3465 was 4-fold less than the %ID/g values in blood from the mice injected with 64Cu-CuCl2. If there was significant transchelation, we would have observed higher %ID/g values in blood in mice injected with 64Cu-AMD3465; however, higher values were not observed. The increase in %ID/g in blood at 600 min also suggests transchelation of copper at later time points. Cross-bridged cyclam-based inhibitors due to stable copper binding may lead to improved copper-based CXCR4 imaging agents (39). Also, possible metabolites such as 64Cu-cyclam have been shown to have low affinity for CXCR4 (40,41), suggesting that the uptake observed in our studies is due to intact 64Cu-AMD3465.

CONCLUSION

We have synthesized and performed a detailed evaluation of 64Cu-AMD3465 as a PET agent to detect CXCR4 expression in tumor models with graded levels of CXCR4 expression. The results presented indicate that AMD3465 may serve as a suitable scaffold for the synthesis of clinically translatable CXCR4-targeted imaging agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Wisconsin team for providing 64Cu-CuCl2; Gilbert Green, Jianhua Yu, David L. Huso, Lauren Hoffman, and Christopher Endres for assistance with imaging and image analysis; and Ronnie Mease, Sangeeta Ray, and Catherine Foss for helpful discussions. This work was partially supported by an anonymous family fund translational research grant from the American Brain Tumor Association (SN), the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund (SN), an Elsa U. Pardee Foundation grant (SN), and a National Cancer Institute grant (U24 CA92871; MGP).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

References

- 1.Chong BF, Mohan C. Targeting the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1147–1153. doi: 10.1517/14728220903196761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steen A, Schwartz TW, Rosenkilde MM. Targeting CXCR4 in HIV cell-entry inhibition. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9:1605–1621. doi: 10.2174/138955709791012265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teicher BA, Fricker SP. CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2927–2931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balkwill F. The significance of cancer cell expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burger JA, Kipps TJ. CXCR4: a key receptor in the crosstalk between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Blood. 2006;107:1761–1767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong D, Korz W. Translating an antagonist of chemokine receptor CXCR4: from bench to bedside. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7975–7980. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J, Takeuchi H, Lam ST, et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in colorectal cancer patients increases the risk for recurrence and for poor survival. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2744–2753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeelenberg IS, Ruuls-Van Stalle L, Roos E. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is required for outgrowth of colon carcinoma micrometastases. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3833–3839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dessein AF, Stechly L, Jonckheere N, et al. Autocrine induction of invasive and metastatic phenotypes by the MIF-CXCR4 axis in drug-resistant human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4644–4654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang Z, Yoon Y, Votaw J, Goodman MM, Williams L, Shim H. Silencing of CXCR4 blocks breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:967–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MC, Luker KE, Garbow JR, et al. CXCR4 regulates growth of both primary and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8604–8612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luker KE, Luker GD. Functions of CXCL12 and CXCR4 in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2006;238:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oda Y, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, et al. CXCR4 and VEGF expression in the primary site and the metastatic site of human osteosarcoma: analysis within a group of patients, all of whom developed lung metastasis. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:738–745. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvucci O, Bouchard A, Baccarelli A, et al. The role of CXCR4 receptor expression in breast cancer: a large tissue microarray study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun YX, Wang J, Shelburne CE, et al. Expression of CXCR4 and CXCL12 (SDF-1) in human prostate cancers (PCa) in vivo. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:462–473. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darash-Yahana M, Pikarsky E, Abramovitch R, et al. Role of high expression levels of CXCR4 in tumor growth, vascularization, and metastasis. FASEB J. 2004;18:1240–1242. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0935fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamamura H, Hori A, Kanzaki N, et al. T140 analogs as CXCR4 antagonists identified as anti-metastatic agents in the treatment of breast cancer. FEBS Lett. 2003;550:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00824-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang EH, Singh B, Cristofanilli M, et al. A CXCR4 antagonist CTCE-9908 inhibits primary tumor growth and metastasis of breast cancer. J Surg Res. 2009;155:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SY, Lee CH, Midura BV, et al. Inhibition of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemokine pathway reduces the development of murine pulmonary metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:201–211. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9133-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin JB, Kung AL, Klein RS, et al. A small-molecule antagonist of CXCR4 inhibits intracranial growth of primary brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235846100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanaoka H, Mukai T, Tamamura H, et al. Development of a 111In-labeled peptide derivative targeting a chemokine receptor, CXCR4, for imaging tumors. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobson O, Weiss ID, Kiesewetter DO, Farber JM, Chen X. PET of Tumor CXCR4 expression with 4-18F-T140. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1796–1804. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nimmagadda S, Pullambhatla M, Pomper MG. Immunoimaging of CXCR4 expression in brain tumor xenografts using SPECT/CT. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1124–1130. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.061325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nimmagadda S, Pullambhatla M, Stone K, Green G, Bhujwalla ZM, Pomper MG. Molecular imaging of CXCR4 receptor expression in human cancer xenografts with [64Cu]AMD3100 positron emission tomography. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3935–3944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson O, Weiss ID, Szajek L, Farber JM, Kiesewetter DO. 64Cu-AMD3100: a novel imaging agent for targeting chemokine receptor CXCR4. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:1486–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fricker SP, Anastassov V, Cox J, et al. Characterization of the molecular pharmacology of AMD3100: a specific antagonist of the G-protein coupled chemokine receptor, CXCR4. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong RS, Bodart V, Metz M, Labrecque J, Bridger G, Fricker SP. Comparison of the potential multiple binding modes of bicyclam, monocylam, and noncyclam small-molecule CXC chemokine receptor 4 inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1485–1495. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodart V, Anastassov V, Darkes MC, et al. Pharmacology of AMD3465: a small molecule antagonist of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatse S, Princen K, De Clercq E, et al. AMD3465, a monomacrocyclic CXCR4 antagonist and potent HIV entry inhibitor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjorndal A, Deng H, Jansson M, et al. Coreceptor usage of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates varies according to biological phenotype. J Virol. 1997;71:7478–7487. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7478-7487.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mease RC, Dusich CL, Foss CA, et al. N-[N-[(S)-1,3-dicarboxypropyl]carbamoyl]-4-[18F]fluorobenzyl-L-cysteine, [18F]DCFBC: a new imaging probe for prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3036–3043. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zagzag D, Krishnamachary B, Yee H, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1α and CXCR4 expression in hemangioblastoma and clear cell-renal cell carcinoma: von Hippel-Lindau loss-of-function induces expression of a ligand and its receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6178–6188. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amara A, Gall SL, Schwartz O, et al. HIV coreceptor downregulation as antiviral principle: SDF-1α-dependent internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 contributes to inhibition of HIV replication. J Exp Med. 1997;186:139–146. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta SK, Pillarisetti K. Cutting edge: CXCR4-Lo—molecular cloning and functional expression of a novel human CXCR4 splice variant. J Immunol. 1999;163:2368–2372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boswell CA, Sun X, Niu W, et al. Comparative in vivo stability of copper-64-labeled cross-bridged and conventional tetraazamacrocyclic complexes. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1465–1474. doi: 10.1021/jm030383m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wadas TJ, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Anderson CJ. Copper chelation chemistry and its role in copper radiopharmaceuticals. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:3–16. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan A, Nicholson G, Greenman J, et al. Binding optimization through coordination chemistry: CXCR4 chemokine receptor antagonists from ultrarigid metal complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3416–3417. doi: 10.1021/ja807921k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerlach LO, Jakobsen JS, Jensen KP, et al. Metal ion enhanced binding of AMD3100 to Asp262 in the CXCR4 receptor. Biochemistry. 2003;42:710–717. doi: 10.1021/bi0264770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerlach LO, Skerlj RT, Bridger GJ, Schwartz TW. Molecular interactions of cyclam and bicyclam non-peptide antagonists with the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14153–14160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.