Abstract

Keratins are the intermediate filament (IF)-forming proteins of epithelial cells. Since their initial characterization almost 30 years ago, the total number of mammalian keratins has increased to 54, including 28 type I and 26 type II keratins. Keratins are obligate heteropolymers and, similarly to other IFs, they contain a dimeric central α-helical rod domain that is flanked by non-helical head and tail domains. The 10-nm keratin filaments participate in the formation of a proteinaceous structural framework within the cellular cytoplasm and, as such, serve an important role in epithelial cell protection from mechanical and non-mechanical stressors, a property extensively substantiated by the discovery of human keratin mutations predisposing to tissue-specific injury and by studies in keratin knockout and transgenic mice. More recently, keratins have also been recognized as regulators of other cellular properties and functions, including apico-basal polarization, motility, cell size, protein synthesis and membrane traffic and signaling. In cancer, keratins are extensively used as diagnostic tumor markers, as epithelial malignancies largely maintain the specific keratin patterns associated with their respective cells of origin, and, in many occasions, full-length or cleaved keratin expression (or lack there of) in tumors and/or peripheral blood carries prognostic significance for cancer patients. Quite intriguingly, several studies have provided evidence for active keratin involvement in cancer cell invasion and metastasis, as well as in treatment responsiveness, and have set the foundation for further exploration of the role of keratins as multifunctional regulators of epithelial tumorigenesis.

Keywords: keratins, cancer, invasion, diagnosis, prognosis, drug resistance

Introduction

The cytoskeleton is a proteinaceous structural framework within the cellular cytoplasm (Fuchs and Cleveland, 1998). Eukaryotic cells contain three main kinds of cytoskeletal filaments, namely microfilaments, intermediate filaments (IFs) and microtubules. Microfilaments are composed of 6-nm intertwined actin chains and are responsible for resisting tension and maintaining cellular shape, forming cytoplasmic protuberances and participating in cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions (Pollard and Cooper, 2009). The 10 nm in diameter IFs are more stable than actin filaments, organize the internal three-dimensional cellular structure and, similarly to microfilaments, also function in cell shape maintenance by bearing tension (Herrmann et al., 2009). Finally, the microtubules are 23 nm in diameter hollow cylinders, most commonly comprising of 13 protofilaments, which in turn are polymers of alpha- and beta-tubulin, and play key roles in intracellular transport and the formation of the mitotic spindle (Glotzer, 2009).

In contrast to actin filaments and microtubules, IFs are encoded by a large family of genes expressed in a tissue- and differentiation state-specific manner and are classified into discrete categories based on their rod domain amino-acid sequence. Types 1 and 2 IFs are found primarily in epithelial cells and include the acidic and basic keratins, respectively; type 3 IFs include vimentin, desmin and glial fibrillary acidic protein; type 4 IFs assemble into neurofilaments; and type 5 IFs are the nuclear lamins (Herrmann et al., 2007). All IFs have a dimeric central rod domain, which is a coiled coil of two parallel α-helices flanked by head and tail domains of variable lengths. Antiparallel molecular dimers (referred to as tetramers) polymerize in a staggered manner to make apolar protofilaments (3 nm in diameter), which in turn associate to protofibrils (4–5 nm in diameter), and then to the 10-nm IFs (Steinert et al., 1993), which are among the most chemically stable cellular structures, resisting high temperature, high salt and detergent solubilization.

In this review, we will focus on keratins, the IFs of epithelial cells and will review their functional role in the normal epithelium and their emergent significance in the pathophysiology and treatment of epithelial malignancies.

Keratins in health

Epithelial cell IFs

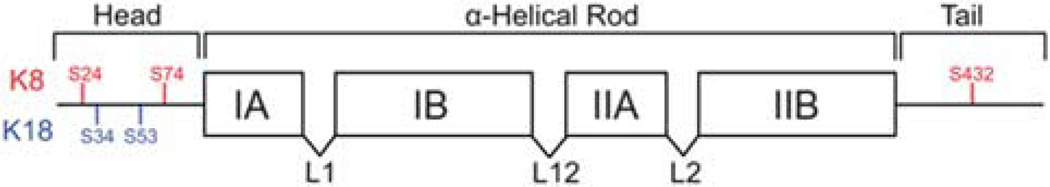

Keratins are the IF-forming proteins of epithelial cells and account for the majority of IF genes in the human genome. Two-dimensional isoelectric focusing and sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were initially used to profile the keratins of normal human epithelial tissues, cell cultures and tumors (Moll et al., 1982), and resulted in the first comprehensive keratin catalog, which included 19 members and separated them into type I (or acidic, K9–K19) and type II (or basic to neutral, K1–8) keratins, and the recognition that keratin filaments form by heterotypic pairing of type I and type II proteins at equimolar amounts (Quinlan et al., 1984). Additional keratins were subsequently identified (Moll et al., 1990; Takahashi et al., 1995), including a large number of hair follicle-specific keratins (Winter et al., 1998). Given the completion of the human genome sequence, a consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratin genes and proteins is now in place (Schweizer et al., 2006) and includes 28 type I (20 epithelial and 11 hair) keratins and 26 type II (20 epithelial and six hair) keratins. Similarly to other IFs, keratins contain a central α-helical domain of about 310 amino acids, which is composed of subdomains 1A, 1B, 2A and 2B connected by linkers L1, L12 and L2 (Figure 1). The non-helical head and tail domains consist of subdomains V1 and H1 and H2 and V2, respectively (Herrmann et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Keratin structure. Keratins form obligate heteropolymers (between one type I and one type II keratin) and share a common structure consisting of a central coiled-coil α-helical rod domain that is flanked by non-helical head and tail domains. The α-helical rod domain is subdivided into four subdomains (coils IA, IB, IIA and IIB), which are connected with three linkers (L1, L12 and L2). Most post-translationally modified sites are found within the head and tail domains (conserved phosphorylation sites on human K8 and K18 are shown).

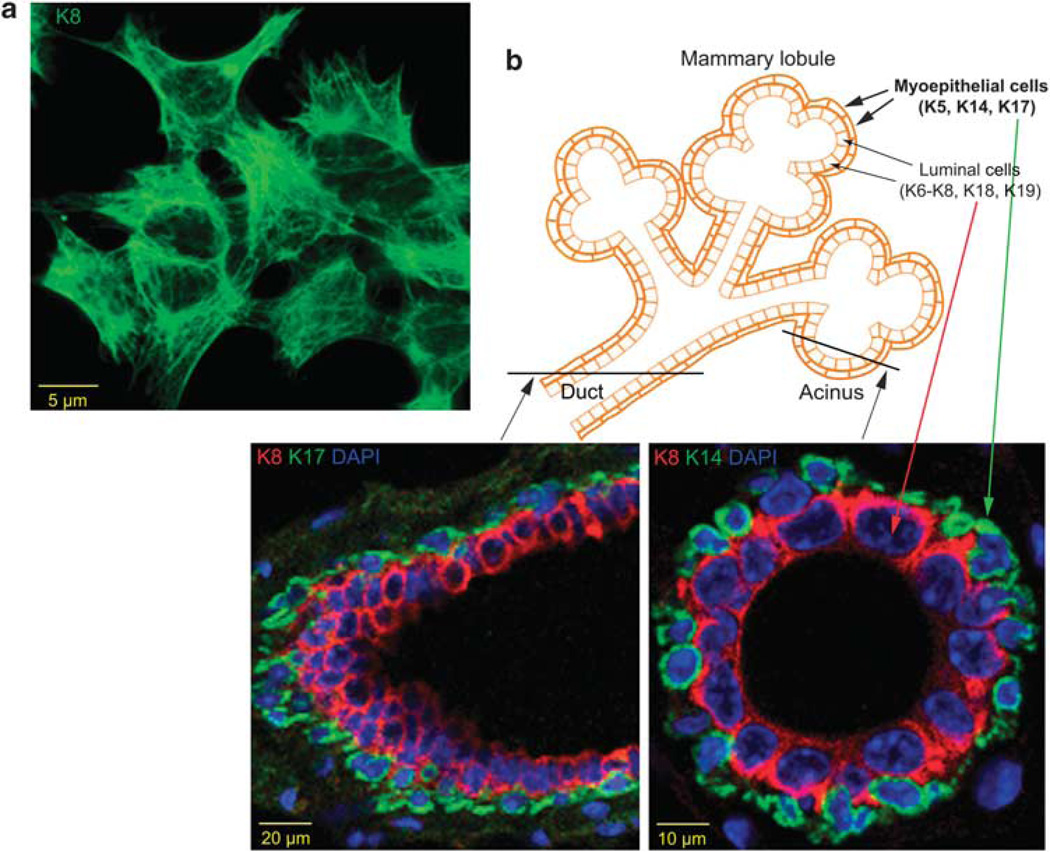

Keratins are expressed in all types of epithelial cells (simple, stratified, keratinized and cornified) (Moll et al., 1982; Bragulla and Homberger, 2009). K8 and its obligate partner K18 constitute the primary keratin pair in many simple epithelial cells, such as hepatocytes, pancreatic acinar and islet cells, and proximal tubular kidney epithelial cells, and are also found in pseudostratified (for example, respiratory) and complex (for example, glandular) epithelia (Figure 2) and the urothelium; K7 and K19 are expressed in other simple epithelial cells, such as duct-lining cells, intestinal cells and mesothelial cells, in pseudostratified epithelia and the urothelium; K20 is expressed in gastrointestinal epithelia, the urothelium and in Merkel (neuroendocrine) cells of the skin; K5 and K14 form the main keratin pair in keratinocytes of stratified squamous epithelia, and are also expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of complex and glandular epithelial tissues; K6 and K16 have been identified in the epidermis, nail epithelia and non-keratinizing stratified squamous epithelia, but are also expressed in ductal luminal cells and in secretory cells of human eccrine sweat glands; K17 is a basal/myoepithelial cell keratin that is characteristically induced after skin injury; K1/K10, K15, K9 and K2 are all expressed in keratinocytes; K3 and K12 are the keratins of corneal epithelium; K4 and K13 are characteristic of mucosal stratified squamous epithelial cells; and K25–K28 and K71–K75 are hair-follicle-specific keratins, whereas K31–K40 and K81–K86 are keratins of the hair fiber (Moll et al., 2008).

Figure 2.

Keratins in mammary epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. (a) K8 immune staining in immortalized mouse mammary epithelial cells (Karantza-Wadsworth and White, 2008) in two-dimensional culture. (b) The mammary gland is a compound tubuloalveolar epithelial cell structure consisting of secretory acini grouped within lobules and draining into intralobular ducts, which in turn drain into interlobular ducts. Lobules are organized into 15–20 lobes emptying into lactiferous sinuses and from there into lactiferous ducts, which open onto the nipple. Ducts (left panel) and acini (right panel) are lined with luminal epithelial cells expressing K8/K18, K19 and K6. These are surrounded by myoepithelial cells, which are characterized by K5, K14 and K17 expression.

Protectors of epithelial cell integrity and much more, and so on

Keratins serve an important role in epithelial cell protection from mechanical and non-mechanical stressors (Coulombe and Omary, 2002), a function that has been particularly well characterized in the skin, cornea and liver by both the discovery of human keratin mutations predisposing to tissue-specific injury (Omary et al., 2009) and the development of keratin knockout (KO) and transgenic mouse models (Vijayaraj et al., 2007). For example, mutations in keratins K5 or K14, which are expressed in the basal cells of stratified epithelial, lead to physical trauma-induced fragility and lysis of these cells resulting in intraepithelial blisters and epidermolysis bullosa simplex (Bonifas et al., 1991; Coulombe et al., 1991; Lane et al., 1992); mutations in the cornea-specific keratins K3 or K12 result in the fragility of the anterior corneal epithelium and intraepithelial microcyst formation (Meesmann’s corneal dystrophy) (Irvine et al., 1997); K8 (Ku et al., 2001) or K18 (Ku et al., 1997) mutations are found as a predisposition to chronic (Omary et al., 2009) and acute (Strnad et al., 2010) liver disease. Similarly, K5-null mice survive for only a few hours after birth and exhibit extensive skin blistering (Peters et al., 2001), whereas K14-null mice show a similar, but less severe, phenotype and die within 3–4 days (Lloyd et al., 1995); K12 KO mice show corneal erosions (Kao et al., 1996); K8 deficiency results in liver hemorrhage and embryonic lethality in C57BL/6 mice (Baribault et al., 1993) together with mechanical fragility and susceptibility to hepatocyte injury during liver perfusion (Loranger et al., 1997), but causes colorectal hyperplasia and inflammation, rectal prolapse and mild liver injury in the FVB strain (Baribault et al., 1994; Habtezion et al., 2005), whereas K18 KO mice exhibit late-onset, subclinical liver pathology (Magin et al., 1998), suggesting different K8 and K18 roles in inflammatory bowel and liver diseases, although K8 mutations do not appear to be associated with human inflammatory bowel disease (Buning et al., 2004; Ku et al., 2007). Transgenic mouse models have yielded complementary results, further underscoring the functional significance of keratins in epithelial health preservation. Mice overexpressing human K18 bearing an Arg89-to-Cys mutation (corresponding to a highly conserved and mutation ‘hot-spot’ arginine residue in human skin disorders) show liver and pancreatic keratin filament disruption, hepatocyte fragility, chronic hepatitis (Ku et al., 1995) and increased susceptibility to a variety of stresses, including hepatotoxic drugs, partial hepatectomy, collagenase liver perfusion and Fas-mediated apoptosis (Ku et al., 1999, 2003b; Zatloukal et al., 2000). Overexpression of the human liver disease-associated K8 Gly61-to-Cys variant results in stress-induced liver injury and apoptosis, and a similar phenotype is observed in transgenic mice overexpressing mutant K8 Ser73-to-Ala (Ku and Omary, 2006).

In addition to their widely accepted role as protectors of epithelial cell integrity under a variety of stressful conditions, keratins have been more recently recognized as important regulators of diverse cellular functions, such as apico-basal polarization (Oriolo et al., 2007), cell size determination and protein translation control (Kim et al., 2006; Vijayaraj et al., 2009), organelle positioning and membrane protein targeting (Styers et al., 2005; Toivola et al., 2005).

Post-translational modifications and protein interactions

In response to stress, keratin expression is commonly altered (Toivola et al., 2010) and keratins become post-translationally modified and structurally reorganized (Ku and Omary, 2006). In keratinocytes, stretching results in K10 suppression and K6 induction (Yano et al., 2004), and wounding upregulates K6, K16 and K17 (Kim et al., 2006). In the liver, K8/K18 levels increase about threefold (mRNA and protein) in response to injury, as noted in mice treated with agents that induce Mallory–Denk body formation (Zatloukal et al., 2007) and in the hepatoma cell line HepG2 treated with doxorubicin (Wang et al., 2009; Hammer et al., 2010), and two- to fourfold (protein) in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (Fickert et al., 2003). In alveolar epithelial cells, shear stress causes structural remodeling of the keratin IF network (Felder et al., 2008; Sivaramakrishnan et al., 2008), whereas hypoxia results in network disassembly and K8/K18 degradation (Na et al., 2010). Similarly, the keratin cytoskeleton disintegrates in mammary epithelial cells under metabolic (combined glucose and oxygen deprivation mimicking the tumor microenvironment; Nelson et al., 2004) stress (Kongara et al., 2010). For mechanical stress, and likely for other types of stress, keratin reorganization involves a temporal sequence of changes that is dependent on stress duration, and consequently stress severity. For example, in alveolar epithelial cells, thin keratin filaments coalesce to tonofibrils/keratin bundles after 1–4 h of shear stress; Mallory-like body formation is observed after 12–16 h of shear stress, and finally, the keratin network collapses by disassembly and ubiquitin-mediated degradation after 24–36 h of shear stress (Ridge et al., 2005; Sivaramakrishnan et al., 2009).

Keratin reorganization under stress is regulated by post-translational modifications and differential keratin association with scaffolding proteins (Coulombe and Omary, 2002). Among the different types of protein modification, phosphorylation is considered a major regulator, as it modulates intrinsic keratin properties, such as solubility, conformation and filament structure, and it also regulates other post-translational modifications (Omary et al., 2006). Keratin phosphorylation occurs at Ser > Thr > Tyr residues within Arg-rich Ser-Arg-Ser-Xaa (Xaa denotes any amino acid) or Leu-Leu-Ser/Thr-Pro-Leu motifs, among others, located within the head and tail keratin domains. The number of phosphates per keratin molecule is keratin-, cell type- and biological context dependent. In general, phosphorylation levels are low in basal conditions, but increase several fold in mitosis (Toivola et al., 2002) and under a variety of cellular stresses, including drug-induced apoptosis (Liao et al., 1997; Schutte et al., 2004), heat stress (Liao et al., 1997), treatment with phosphatase inhibitors (Toivola et al., 2002), shear stress (Ridge et al., 2005) and metabolic stress (Kongara et al., 2010). Three human K8 (S23, S73, S431) and two K18 (S33, S52) major in vivo phosphorylation sites have been characterized (Ku and Omary, 2006), and potentially involved kinases have been primarily determined by in vitro studies and appear to be at least partially stress dependent. For example, K8 phosphorylation at Ser73 is mediated by the two stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase family members p38 and c-jun-N-terminal kinase in response to the phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid and orthovanadate (Ku et al., 2002a; Woll et al., 2007) and upon stimulation of the proapoptotic receptor Fas/CD95/Apo-1 (He et al., 2002), respectively, and by protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) under mechanical stress (Ridge et al., 2005). Phosphorylation regulates the distribution of keratins into an ‘insoluble’ filamentous cytoskeletal pool and a ‘soluble’ cytosolic or detergent-extractable hyperphosphorylated pool (Omary et al., 1998) and plays a role in keratin ubiquitination and turnover by the proteasome (Ku and Omary, 2000; Jaitovich et al., 2008), and likely by autophagy (Kongara et al., 2010). Phosphorylation is also important for the interaction of keratins with keratin-associated proteins, among them the adapter/signaling 14-3-3 proteins, which are involved in keratin solubilization during mitosis by binding to phospho(Ser33)-K18 and undergoing nuclear-to-cytoplasmic redistribution (Ku et al., 2002b) and in serum-dependent Akt/mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway activation by binding to phospho (Ser44)-K17 and again relocating from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Kim et al., 2006).

Keratins in cancer

Diagnostic markers in epithelial tumors

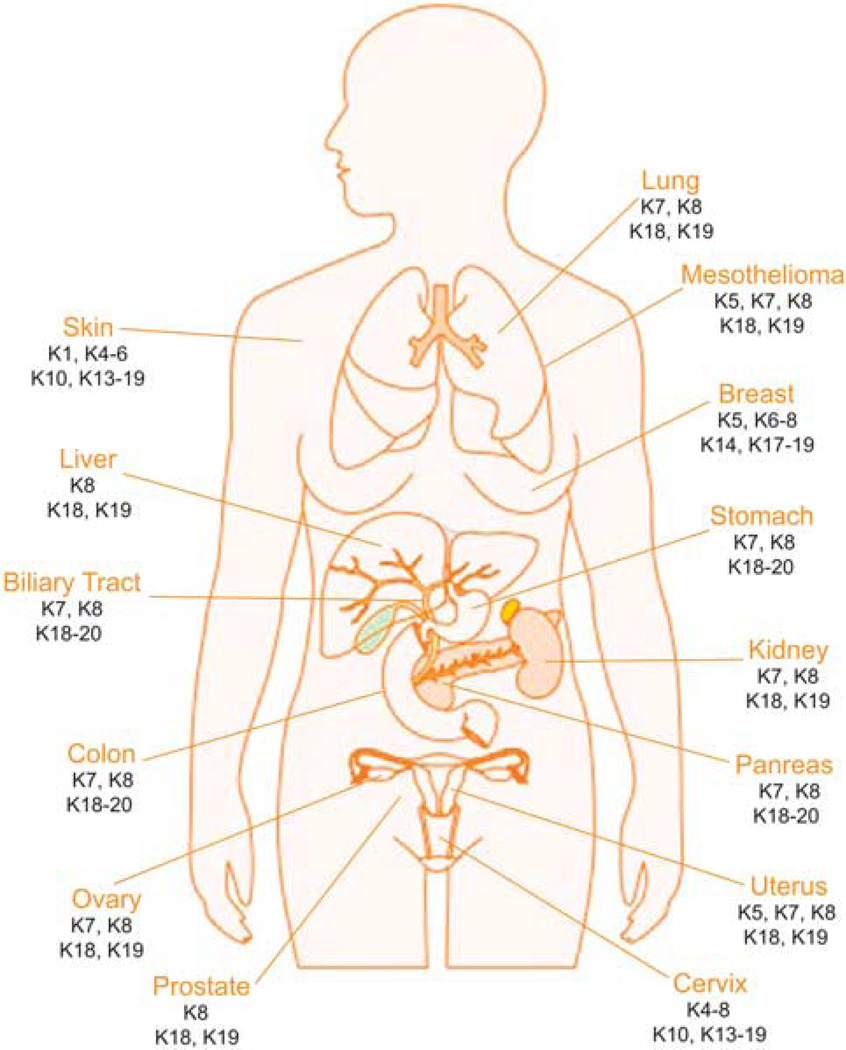

Given the characteristic cell type-, differentiation- and functional status-dependent keratin expression patterns in epithelial cells, the availability of specific keratin antibodies, and the fact that epithelial tumors largely maintain the features of specific keratin expression associated with the respective cell type of origin, keratins have long and extensively been used as immunohistochemical markers in diagnostic tumor pathology (Figure 3; Table 1) (Moll et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

Keratin expression in human cancer. Keratins are normally expressed in a cell type-, differentiation- and functional status-dependent manner, and epithelial cancers largely maintain the characteristics of keratin expression associated with their respective cell type of origin, so keratins have long been recognized as diagnostic markers in tumor pathology. Examples of keratins commonly used in the diagnosis of human epithelial malignancies are presented here.

Table 1.

Keratins as diagnostic markers in tumor pathology

| Cancer site and subtype | Keratin expression |

|---|---|

| Biliary duct | K7, K8, K18–20 |

| Bladder, transitional cell | K5a, K7, K8, K18, K19, K20a |

| Breast | K5a,b, K6a,b, K7, K8, K14a,b, K17a,b, K18, K19 |

| Cervix | K4–8, K10, K13–19 |

| Colon | K7a, K8, K18–20 |

| Kidney, clear cell | K8, K18, K19a |

| Papillary | K7, K8, K18, K19 |

| Chromophobe | K7, K8, K18, K19a |

| Liver | K7a, K8, K18, K19a, K20a |

| Lung, adenocarcinoma | K7, K8, K18, K19 |

| Small cell | K8, K18, K19a |

| Ovary, adenocarcinomac | K7, K8, K18, K19 |

| Pancreas | K5a, K7, K8, K18, K19, K20a |

| Pleura (mesothelioma) | K5, K7a, K8, K18, K19 |

| Prostate | K8, K18, K19 |

| Skin, squamous | K1, K4–6, K8d, K10, K13–17, K18d, K19d |

| Merkel cell | K8, K18, K20 |

| Stomach | K7a, K8, K18, K19, K20a |

| Uterus | K5a, K7, K8, K18, K19 |

Focal/heterogeneous staining in some, but not all, cases.

Focal or extended staining in basal-like tumors.

Non-mucinous.

In poorly differentiated cases.

Adenocarcinomas, that is, epithelial cancers arising in glandular tissues, comprise the largest group of human epithelial malignancies and may arise in different organs. The ability to differentiate adenocarcinomas according to their tissue of origin is essential for the selection of the most appropriate treatment regimens, and simple epithelial keratins are the markers predominantly used for this purpose. Most adenocarcinomas express the simple epithelial keratins K8, K18 and K19, whereas K7 and K20 expression is variable. Keratin typing is of particular diagnostic significance in the case of colorectal adenocarcinomas, which similarly to the normal gastrointestinal epithelium are almost always K20-positive, but K7-negative (or have lower K7 expression compared with K20) (Moll et al., 2008). K20 and K7 co-expression has been reported as a characteristic of more advanced colorectal cancers (Hernandez et al., 2005), whereas reduced K20 levels have been detected in association with high microsatellite instability (McGregor et al., 2004). Pancreatic, biliary tract, esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas uniformly express K7 and more variably, but up to 65%, K20 (Chu et al., 2000), whereas a K7+/K20− phenotype is characteristic of ovarian, endometrial and lung adenocarcinomas (Moll et al., 2008). Endometrial adenocarcinomas may co-express stratified epithelial keratins, such as K5, as an indication of squamous metaplasia (Chu and Weiss, 2002a). Non-squamous, malignant salivary gland carcinomas are also K7+/K20−, with the exception of salivary duct carcinomas, which may be positive for both keratins (Nikitakis et al., 2004). Furthermore, almost all thyroid tumors (follicular, papillary and medullary subtypes) and two-thirds of malignant mesothelioma cases are K7+/K20−. The latter tumors, in contrast to most adenocarcinomas, consistently express keratinocyte-type keratins, notably K5, and vimentin (Yaziji et al., 2006). Appendiceal and lung carcinoids, adrenal cortical, prostatic and hepatocellular carcinomas are negative for both K7 and K20 (Chu and Weiss, 2002b).

Most breast adenocarcinomas, including both ductal and lobular subtypes, constitutively express K7, K8, K18 and K19. However, K8 exhibits a predominantly peripheral staining pattern in ductal carcinoma as compared to a ring-like, perinuclear pattern in lobular carcinoma (Lehr et al., 2000). In poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas corresponding to the basal-like subtype as defined by microarray-based expression profiling of breast tumors (Sorlie et al., 2001), keratins characteristic of the basal cells of stratified epithelium, such as K5/6, K14 and K17, are also expressed. More recently, phospho(Ser73)-K8 was identified as a possible biomarker for lower beclin1 expression, and thus defective autophagy status, in breast tumors (Kongara et al., 2010).

Keratin expression is a particularly useful guide in the correct classification of renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) (Liu et al., 2007), as clear-cell RCCs mainly express K8 and K18 with minor K19 expression, papillary tumors strongly express K19 and K7 in addition to the basic K8/K18 pair and chromophobe RCCs typically express K7 and K8/K18, but little K19. Benign oncocytomas may histologically resemble chromophobe RCCs, but are K7 negative (Liu et al., 2007). Transitional cell carcinomas generally conserve the urothelial keratin pattern showing combined expression of K8/K18, K7 and K19 together with K13 and K20 (Moll et al., 1992).

Squamous cell carcinomas, independently of their site of origin, are characterized by the expression of the stratified epithelial keratins K5, K14 and K17 and the hyperproliferative keratinocyte-type keratins K6 and K16 (Moll et al., 2008). K1/K10 may also be focally expressed, and K4 and K13 to a lesser extent. In poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinomas, co-expression of the simple epithelial keratins K8, K18 and K19 is often observed.

Use of keratins as diagnostic markers in tumor pathology is by far their most common application in the field of cancer. In cases remaining unclear on the basis of clinical presentation and conventional histopathology, including carcinomas that are poorly differentiated or spreading over several organs and metastases of unknown primary tumor site, keratin typing is especially valuable for correct tumor identification and subsequent selection of the most appropriate treatment plan.

Prognostic markers in epithelial tumors

Beyond their well-established role as diagnostic markers in cancer, keratins have also been recognized as prognostic indicators in a variety of epithelial malignancies (Table 2). For example, in colorectal cancer, reduced expression of K8 and K20 has been associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal cancer cell transition, which is generally indicative of higher tumor aggressiveness, and decreased patient survival (Knosel et al., 2006). Also, persistent or higher expression of a caspase-cleaved K18 fragment at Asp396 (produced by apoptotic epithelial cells and detected by an epitope-specific antibody M30) in the serum of colon cancer patients after primary tumor resection is indicative of systemic residual tumor load and significantly correlates with recurrence risk within 3 years (Ausch et al., 2009). Higher serum-cleaved K18/M30 levels before treatment are also predictive of shorter survival in lung cancer patients (Ulukaya et al., 2007). More recently, the ratio of caspase cleaved (M30) to total K18 (M65), conveniently determined in the serum or plasma using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits, is being explored as a biomarker for therapy efficacy monitoring in carcinoma patients (Linder et al., 2010). Similarly, in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a high serum K19 fragment (CYFRA21-1) concentration is associated with decreased recurrence-free and overall survival (Uenishi et al., 2008). Intratumoral K20 expression and K20 positivity in the bone marrow and/or blood correlate with worse prognosis in pancreatic adenocarcinomas (Soeth et al., 2005; Matros et al., 2006; Schmitz-Winnenthal et al., 2006). Furthermore, in gastric cancer, real-time quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction for K20 in peritoneal lavage fluid predicts peritoneal recurrence in patients undergoing resection with curative intent (Katsuragi et al., 2007); K10 and K19 positivity in hepatocellular carcinomas are significant predictors of shorter overall and disease-free survival after surgical resection (Yang et al., 2008); and absence of squamous differentation as evidenced by loss of K5/6 expression is associated with more aggressive endometrial carcinomas and reduced survival (Stefansson et al., 2006). In clear-cell RCC, tumoral co-expression of K7 and K19 is associated with the lack of cytogenetic alterations, low nuclear grade and better clinical outcome (Mertz et al., 2008), whereas detection of K8/18-positive circulating tumor cells correlates with positive lymph node status, presence of synchronous metastases at the time of primary tumor resection and poor overall survival in renal cell cancer (Bluemke et al., 2009). Detection of disseminated keratin-positive tumor cells in the bone marrow of prostate cancer patients before surgery is an independent risk factor for metastasis within 48 months (Weckermann et al., 2009). In skin cancer, keratin expression in malignant melanoma is of particular interest, as K18 mRNA is surprisingly identified in one-third of melanoma tissue samples and is an adverse prognostic factor (Chen et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Keratins as prognostic markers in tumor pathology

| Cancer site | Keratin expression pattern |

Detection site |

Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biliary duct | High K19 fragment (CYFRA21-1) | Serum | Worse |

| Breast | K5/6, K17 | Tumor | Worse |

| K19 mRNA | CTCsa | Worse | |

| Reduced K18 mRNA | Tumor | Worse | |

| Ubiquitinated K8 and K18 fragments | Tumor | Worse | |

| Colon | Reduced K8, K20 | Tumor | Worse |

| Persistent or higher K18 fragment (M30) after primary tumor resection | Serum | Worse | |

| Kidney | K8, K18 | CTCsa | Worse |

| K7, K19 | Tumor | Better | |

| Liver | K10, K19 | Tumor | Worse |

| Lung | High K18 fragment (M30) | Serum | Worse |

| Pancreas | K20 | Tumor | Worse |

| K20 | Serum | Worse | |

| Prostate | K8, K18, K19 before surgery | Bone marrow | Worse |

| Skin (melanoma) | K18 | Tumor | Worse |

| Stomach | K20 | Peritoneal fluid | Worse |

| Uterus | Loss of K5/K6 | Tumor | Worse |

Circulating tumor cells.

In breast cancer, the molecularly defined basal-like subtype characterized by estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 negativity, but epidermal growth factor receptor and K5/6 positivity, is associated with younger patient age, high tumor grade and poor prognosis, including shorter disease-free and overall survival (Cheang et al., 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2009). Expression of K17 in breast tumors is also prognostic of poor clinical outcome and this is independent of tumor size and grade in node-negative disease (van de Rijn et al., 2002). Detection of K19 mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells before adjuvant chemotherapy predicts reduced disease-free and overall survival in patients with ER-negative, triple-negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor2-positive early breast tumors (Ignatiadis et al., 2007), whereas the presence of K19 mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells in the blood after completion of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with early breast cancer of any subtype indicates the presence of chemotherapy-resistant residual disease and is again associated with higher risk of disease recurrence and decreased patient survival (Xenidis et al., 2009). Gene expression profiling has indicated that K18 is frequently downregulated in metastatic breast cancer (Hedenfalk et al., 2001; Zajchowski et al., 2001), a finding associated with advanced tumor stage and grade, bone marrow micrometastasis, and shorter cancer-specific survival and overall survival (Woelfle et al., 2003, 2004). Also, ubiquitin-immunoreactive degradation products of K8 and K18 are detected in breast carcinomas and may determine tumor aggressiveness (Iwaya et al., 2003).

Functional role in tumorigenesis

Given their emerging regulatory role in normal cell physiology and their frequently altered expression in cancer, the question as to whether keratins play any functional role in epithelial tumorigenesis arises. Although most keratin KO and transgenic mice do not have any apparent tumor phenotype, K8 deficiency (in the FVB background) results in colorectal hyperplasia and inflammation (Baribault et al., 1994; Habtezion et al., 2005), and also affects (shortens) the latency, but not the incidence or the morphological features of polyoma middle T-induced mammary adenocarcinomas (Baribault et al., 1997); human K8 overexpression results in early neoplastic-like alterations in the pancreas, including loss of acinar architecture, dysplasia and increased cell proliferation (Casanova et al., 1999), and correlates with the extent of spontaneous pancreatic injury (Toivola et al., 2008); and finally, ectopic expression of K8 in the skin causes epidermal hyperplasia in young mice, epidermal atypia and preneoplastic changes in aging mice, and malignant progression of benign skin tumors induced by chemical skin carcinogenesis assays (Casanova et al., 2004).

Several studies have provided evidence supporting an active keratin role in cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Transfection of K8 and K18 in mouse L cells, which are fibroblasts and express vimentin, results in keratin filament formation and is associated with deformability and higher migratory and invasive abilities, indicating that keratins may influence cell shape and migration through interactions with the extracellular environment (Chu et al., 1993). Similarly, experimental co-expression of vimentin and K8/K18 increases invasion and migration of human melanoma (Chu et al., 1996) and breast cancer (Hendrix et al., 1997) cells in vitro.

Incubation of human pancreatic cancer cells with sphingosylphosphorylcholine, a bioactive lipid present in high-density lipoprotein particles and found at increased levels in the blood and malignant ascites from ovarian cancer patients, induces keratin reorganization to a perinuclear, ring-like structure, which is accompanied by K8 and K18 phosphorylation at Ser431 and Ser52, respectively (Beil et al., 2003). This change in the keratin network architecture results in increased cellular elasticity and enhanced cell migration, indicating that sphingosylphosphorylcholine -induced keratin remodeling may directly contribute to the metastatic potential of epithelial cancer cells (Suresh et al., 2005). Cell deformability is also increased in association with keratin network alterations owing to sphingosylphosphorylcholine, likely resulting in greater cancer cell ability to invade the surrounding tissue and permeate through the stroma, and thus facilitating its escape from the primary tumor (Rolli et al., 2010). Furthermore, recent work has implicated alterations in keratin phosphorylation as a contributing factor to colorectal cancer progression, as K8 is a physiological substrate of phosphatase of regenerating liver-3, which is known to promote invasiveness and the metastatic potential of colorectal cancer cells, and high phosphatase of regenerating liver-3 levels are associated with reduction or loss of phosphorylated K8 at the invasive front of human colorectal cancer specimens and in liver metastases (Mizuuchi et al., 2009).

Several studies have explored the role of keratins in cancer cell invasion by investigating K8-mediated plasminogen activation to the serine protease plasmin, which is involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and, as such, in tumor progression and metastasis. Plasminogen is activated on the cell surface by the urokinase-type plasminogen activator bound to urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor and the C-terminal domain of K8 that penetrates the cellular membrane (K8 ectoplasmic domain), as shown in hepatocellular and breast carcinoma cells (Hembrough et al., 1995). Although unlikely that keratin makes it to the cell surface through the regular secretory pathway (Riopel et al., 1993), a monoclonal antibody to the K8 ectoplasmic domain prevents urokinase-type plasminogen activator binding and inhibits plasmin generation, which in turn results in altered cell morphology, greater cell adhesion to fibronectin and reduced breast cancer cell invasion potential (Obermajer et al., 2009), indicating that K8 together with urokinase-type plasminogen activator, plasminogen and fibronectin form a signaling platform that can modulate cell adhesion and invasiveness of breast cancer cells.

K18 may play a regulatory role in hormonally responsive breast cancer, as it can effectively associate with and sequester the ERα target gene and ERα coactivator LRP16 in the cytoplasm, thus attenuating ERα-mediated signaling and estrogen-stimulated cell cycle progression in breast tumor cells (Meng et al., 2009). Furthermore, autophagy defects, which promote mammary tumorigenesis (Karantza-Wadsworth et al., 2007), result in K8, K17 and K19 upregulation in mouse mammary tumor cells under metabolic stress in vitro and in allograft mouse mammary tumors in vivo (Kongara et al., 2010), potentially implicating deregulation of keratin homeostasis in defective autophagy-associated breast cancer, a hypothesis worthy of further investigation. Defective autophagy has also been implicated in abnormal keratin accumulation in the liver, as Mallory–Denk body-like inclusion formation, which is a common finding in hepatocellular carcinomas, is directly affected by pharmacological autophagy modulation (Harada et al., 2008).

Keratin 17, which is rapidly induced in wounded stratified epithelia, regulates cell size and growth by binding to the adaptor protein 14-3-3σ and stimulating the mTOR pathway, thus regulating protein synthesis (Kim et al., 2006). Additional evidence that keratins may function upstream of mTOR is provided by studies in mice with ablation of all keratin genes, where embryonic lethality from severe growth retardation is associated with aberrant localization of the glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3m resulting in adenosine monophosphate kinase activation and suppression of the mTORC1 downstream targets S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 (Vijayaraj et al., 2009). In an apparently reciprocal relationship, AKT isoforms regulate intermediate filament expression in epithelial cancer cell lines, as overexpression of AKT1 increases K8/K18 levels and AKT2 upregulates K18 and vimentin (Fortier et al., 2010). Thus, keratins, which are often aberrantly expressed in epithelial cancers, interact in multiple ways with the AKT/mTOR pathway, which itself is frequently abnormally activated in aggressive tumors, raising the possibility that the role of AKT in epithelial tumorigenesis is at least partially keratin mediated and/or dependent.

Keratins are also important for chaperone-mediated intracellular signaling, which may in turn play a role in epithelial tumorigenesis. Atypical PKC is an evolutionarily conserved key regulator of cellular asymmetry, which has also been identified as an oncogene causative of non-small-cell lung cancer and a predisposing factor for colon cancer, when overexpressed (Fields and Regala, 2007). Recent work showed that both filamentous keratins and heat-shock protein 70 are required for the rescue rephosphorylation of mature atypical PKC, thus regulating its subcellular distribution and maintaining its steady-state levels and activity (Mashukova et al., 2009). Furthermore, given an excess of soluble heat-shock protein 70, the keratin network was expected to be a rate-limiting step in the atypical PKC rescue mechanism, a hypothesis confirmed in two different K8-overexpression animal models (Mashukova et al., 2009). In both cases, cellular regions with abnormal and excessive intermediate filament accumulation also exhibited grossly mislocalized active atypical PKC signal, indicating that chaperone-assisted oncogenic kinase activity, including Akt1, may also depend on keratins and expanding on already available knowledge on the role of keratins as chaperone scaffolds (van den et al., 1999; Toivola et al., 2010).

Although K8 mutations have been implicated in the progression of acute and chronic (Ku et al., 2001) liver disease, they have not been directly linked to hepatocellular, pancreatic (Treiber et al., 2006) or any other carcinoma. To date, the only keratin and tumor type for which a specific variant or single-nucleotide polymorphism has been associated with cancer predisposition is K5 in basal cell carcinoma (Stacey et al., 2009), as a genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism association scan for common basal cell carcinoma risk variants identified the G138E substitution in K5 as conferring susceptibility to basal cell carcinoma, but not to squamous cell carcinoma, cutaneous melanoma or fair-pigmentation traits. Given the increasing number of genome-wide association studies for different cancers, it is possible that additional keratin variants influencing specific cancer risk may be discovered in the near future.

Role in drug responsiveness

Keratins protect epithelial cells from mechanical stress, but also provide resistance to other cellular stressors that can lead to cell death, including death receptor activation and chemotherapeutic drugs. For example, K8- and K18-null mice, which lack keratin intermediate filaments in their hepatocytes owing to keratin instability when the partner keratin is missing, and hepatocytes cultured ex vivo from K8-null mice are more sensitive to Fas-mediated apoptosis than their wild-type counterparts (Gilbert et al., 2001). Similarly, a K18 mutation (Arg89Cys) disrupting the keratin filament network predisposes hepatocytes to Fas- but not tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptotic injury (Ku et al., 2003b). These findings clearly show that K8 and K18 mediate resistance to Fas-induced apoptosis in the liver; however, they may also be relevant to cancer therapy, as keratin levels are affected by anticancer drugs, such as mitoxantrone (MX) (Cress et al., 1988) and doxorubicin (Hammer et al., 2010), and proapoptotic receptor agonists may have selective antitumor activity, as activation of the extrinsic apoptotic cell death pathway by binding of the apoptosis ligand 2/tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand to cognate death receptors results in apoptosis of different cancer cell types without significant toxicity toward normal cells (Ashkenazi, 2008; Gonzalvez and Ashkenazi, 2010).

Aberrant keratin expression has already been shown to confer a multidrug resistance phenotype, as mouse L fibroblasts are rendered resistant to MX, doxorubicin, methotrexate, melphalan and vincristine, but not to ionizing radiation, upon K8 and K18 transfection (Bauman et al., 1994). Similarly, NIH 3T3 fibroblasts with ectopic K8/K18 expression exhibit resistance to MX, doxorubicin, bleomycin, mitomycin C and melphalan, but not to cisplatin (Anderson et al., 1996). Furthermore, monocyte chemoattractant protein-7/MX, an MX-selected human breast cancer cell line with a multidrug resistance phenotype owing to overexpression of the breast cancer resistant protein, also exhibits elevated K8 levels, which synergize with breast cancer resistant protein in increasing drug resistance, likely acting via different mechanisms, as anti-K8 short hairpin RNA reverses MX resistance without promoting intracellular drug accumulation as breast cancer resistant protein knockdown does (Liu et al., 2008b). The multidrug resistance of monocyte chemoattractant protein-7/MX cells is at least partially owing to their increased adhesion to the extracellular matrix, which is in turn mediated by K8 expression on the cell surface, indicating that alterations in the expression level and cellular localization of K8 may actively decrease response to cancer treatment (Liu et al., 2008a). Whether pharmacological keratin modulation can be used as an adjunct to chemotherapy for improving therapeutic outcomes remains to be explored.

Concluding remarks

Keratins are important protectors of epithelial structural integrity under conditions of stress, but have also been recognized as regulators of other cellular functions, including motility, signaling, growth and protein synthesis. In cancer, keratins have traditionally been used as diagnostic tools, but accumulating evidence points to their importance as prognostic markers and, more interestingly, as active regulators of epithelial tumorigenesis and treatment responsiveness. Further investigation into the multifunctional role of keratins in cancer is warranted, and will hopefully result in the emergence of improved diagnostic and prognostic markers and the identification of novel therapeutic targets, in turn leading to earlier cancer detection and the rational design of more efficacious cancer therapies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grant R00CA133181 and a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator Award (VK).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest

References

- Anderson JM, Heindl LM, Bauman PA, Ludi CW, Dalton WS, Cress AE. Cytokeratin expression results in a drug-resistant phenotype to six different chemotherapeutic agents. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A. Directing cancer cells to self-destruct with proapoptotic receptor agonists. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:1001–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrd2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausch C, Buxhofer-Ausch V, Olszewski U, Hinterberger W, Ogris E, Schiessel R, et al. Caspase-cleaved cytokeratin 18 fragment (M30) as marker of postoperative residual tumor load in colon cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1164–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baribault H, Penner J, Iozzo RV, Wilson-Heiner M. Colorectal hyperplasia and inflammation in keratin 8-deficient FVB/N mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2964–2973. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baribault H, Price J, Miyai K, Oshima RG. Mid-gestational lethality in mice lacking keratin 8. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1191–1202. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baribault H, Wilson-Heiner M, Muller W, Penner J, Bakhiet N. Functional analysis of mouse keratin 8 in polyoma middle T-induced mammary gland tumours. Transgenic Res. 1997;6:359–367. doi: 10.1023/a:1018427215923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman PA, Dalton WS, Anderson JM, Cress AE. Expression of cytokeratin confers multiple drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5311–5314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beil M, Micoulet A, von Wichert G, Paschke S, Walther P, Omary MB, et al. Sphingosylphosphorylcholine regulates keratin network architecture and visco-elastic properties of human cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:803–811. doi: 10.1038/ncb1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluemke K, Bilkenroth U, Meye A, Fuessel S, Lautenschlaeger C, Goebel S, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with renal cell carcinoma correlates with prognosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2190–2194. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifas JM, Rothman AL, Epstein EH., Jr Epidermolysis bullosa simplex: evidence in two families for keratin gene abnormalities. Science. 1991;254:1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1720261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragulla HH, Homberger DG. Structure and functions of keratin proteins in simple, stratified, keratinized and cornified epithelia. J Anat. 2009;214:516–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buning C, Halangk J, Dignass A, Ockenga J, Deindl P, Nickel R, et al. Keratin 8 Y54H and G62C mutations are not associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:388–391. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova ML, Bravo A, Martinez-Palacio J, Fernandez-Acenero MJ, Villanueva C, Larcher F, et al. Epidermal abnormalities and increased malignancy of skin tumors in human epidermal keratin 8-expressing transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2004;18:1556–1558. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1683fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova ML, Bravo A, Ramirez A, Morreale de Escobar G, Were F, Merlino G, et al. Exocrine pancreatic disorders in transsgenic mice expressing human keratin 8. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1587–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavestro GM, Frulloni L, Nouvenne A, Neri TM, Calore B, Ferri B, et al. Association of keratin 8 gene mutation with chronic pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:416–420. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R, Rossitto PV, Edwards BF, Cardiff RD. Presence of proteolytically processed keratins in the culture medium of MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6353–6359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheang MC, Voduc D, Bajdik C, Leung S, McKinney S, Chia SK, et al. Basal-like breast cancer defined by five biomarkers has superior prognostic value than triple-negative phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1368–1376. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Gong J, Chen X, Xu M, Huang Y, Wang L, et al. Cytokeratin expression in malignant melanoma: potential application of in-situ hybridization analysis of mRNA. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:87–93. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283252feb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu P, Wu E, Weiss LM. Cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 expression in epithelial neoplasms: a survey of 435 cases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:962–972. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu PG, Weiss LM. Expression of cytokeratin 5/6 in epithelial neoplasms: an immunohistochemical study of 509 cases. Mod Pathol. 2002a;15:6–10. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu PG, Weiss LM. Keratin expression in human tissues and neoplasms. Histopathology. 2002b;40:403–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu YW, Runyan RB, Oshima RG, Hendrix MJ. Expression of complete keratin filaments in mouse L cells augments cell migration and invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4261–4265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu YW, Seftor EA, Romer LH, Hendrix MJ. Experimental coexpression of vimentin and keratin intermediate filaments in human melanoma cells augments motility. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:63–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe PA, Hutton ME, Letai A, Hebert A, Paller AS, Fuchs E. Point mutations in human keratin 14 genes of epidermolysis bullosa simplex patients: genetic and functional analyses. Cell. 1991;66:1301–1311. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90051-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe PA, Omary MB. ‘Hard‘ and ‘soft‘ principles defining the structure, function and regulation of keratin intermediate filaments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:110–122. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cress AE, Roberts RA, Bowden GT, Dalton WS. Modification of keratin by the chemotherapeutic drug mitoxantrone. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:3043–3046. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder E, Siebenbrunner M, Busch T, Fois G, Miklavc P, Walther P, et al. Mechanical strain of alveolar type II cells in culture: changes in the transcellular cytokeratin network and adaptations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L849–L857. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00503.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickert P, Trauner M, Fuchsbichler A, Stumptner C, Zatloukal K, Denk H. Mallory body formation in primary biliary cirrhosis is associated with increased amounts and abnormal phosphorylation and ubiquitination of cytokeratins. J Hepatol. 2003;38:387–394. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields AP, Regala RP. Protein kinase C iota: human oncogene, prognostic marker and therapeutic target. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier AM, Van Themsche C, Asselin E, Cadrin M. Akt isoforms regulate intermediate filament protein levels in epithelial carcinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:984–988. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Cleveland DW. A structural scaffolding of intermediate filaments in health and disease. Science. 1998;279:514–519. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert S, Loranger A, Daigle N, Marceau N. Simple epithelium keratins 8 and 18 provide resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis. The protection occurs through a receptor-targeting modulation. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:763–773. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M. The 3Ms of central spindle assembly: microtubules, motors and MAPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalvez F, Ashkenazi A. New insights into apoptosis signaling by Apo2L/TRAIL. Oncogene. 2010;29:4752–4765. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habtezion A, Toivola DM, Butcher EC, Omary MB. Keratin-8-deficient mice develop chronic spontaneous Th2 colitis amenable to antibiotic treatment. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1971–1980. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer E, Bien S, Salazar MG, Steil L, Scharf C, Hildebrandt P, et al. Proteomic analysis of doxorubicin-induced changes in the proteome of HepG2cells combining 2-D DIGE and LC-MS/MS approaches. Proteomics. 2010;10:99–114. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M, Strnad P, Toivola DM, Omary MB. Autophagy modulates keratin-containing inclusion formation and apoptosis in cell culture in a context-dependent fashion. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:1753–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T, Stepulak A, Holmstrom TH, Omary MB, Eriksson JE. The intermediate filament protein keratin 8 is a novel cytoplasmic substrate for c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10767–10774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedenfalk I, Duggan D, Chen Y, Radmacher M, Bittner M, Simon R, et al. Gene-expression profiles in hereditary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102223440801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembrough TA, Vasudevan J, Allietta MM, Glass WF, II, Gonias SL. A cytokeratin 8-like protein with plasminogen-binding activity is present on the external surfaces of hepatocytes, HepG2 cells and breast carcinoma cell lines. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Part 3):1071–1082. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJ, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Trevor KT. Experimental co-expression of vimentin and keratin intermediate filaments in human breast cancer cells results in phenotypic interconversion and increased invasive behavior. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:483–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Bar H, Kreplak L, Strelkov SV, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:562–573. doi: 10.1038/nrm2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Strelkov SV, Burkhard P, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: primary determinants of cell architecture and plasticity. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1772–1783. doi: 10.1172/JCI38214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez BY, Frierson HF, Moskaluk CA, Li YJ, Clegg L, Cote TR, et al. CK20 and CK7 protein expression in colorectal cancer: demonstration of the utility of a population-based tissue microarray. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatiadis M, Xenidis N, Perraki M, Apostolaki S, Politaki E, Kafousi M, et al. Different prognostic value of cytokeratin-19 mRNA positive circulating tumor cells according to estrogen receptor and HER2 status in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5194–5202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.7762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine AD, Corden LD, Swensson O, Swensson B, Moore JE, Frazer DG, et al. Mutations in cornea-specific keratin K3 or K12 genes cause Meesmann’s corneal dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1997;16:184–187. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaya K, Ogawa H, Mukai Y, Iwamatsu A, Mukai K. Ubiquitin-immunoreactive degradation products of cytokeratin 8/18 correlate with aggressive breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:864–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaitovich A, Mehta S, Na N, Ciechanover A, Goldman RD, Ridge KM. Ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of keratin intermediate filaments in mechanically stimulated A549 cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25348–25355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801635200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao WW, Liu CY, Converse RL, Shiraishi A, Kao CW, Ishizaki M, et al. Keratin 12-deficient mice have fragile corneal epithelia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2572–2584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karantza-Wadsworth V, Patel S, Kravchuk O, Chen G, Mathew R, Jin S, et al. Autophagy mitigates metabolic stress and genome damage in mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1621–1635. doi: 10.1101/gad.1565707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. A mouse mammary epithelial cell model to identify molecular mechanisms regulating breast cancer progression. Methods Enzymol. 2008;446:61–76. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01604-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuragi K, Yashiro M, Sawada T, Osaka H, Ohira M, Hirakawa K. Prognostic impact of PCR-based identification of isolated tumour cells in the peritoneal lavage fluid of gastric cancer patients who underwent a curative R0 resection. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:550–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Wong P, Coulombe PA. A keratin cytoskeletal protein regulates protein synthesis and epithelial cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature04659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knosel T, Emde V, Schluns K, Schlag PM, Dietel M, Petersen I. Cytokeratin profiles identify diagnostic signatures in colorectal cancer using multiplex analysis of tissue microarrays. Cell Oncol. 2006;28:167–175. doi: 10.1155/2006/354295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongara S, Kravchuk O, Teplova I, Lozy F, Schulte J, Moore D, et al. Autophagy regulates keratin 8 homeostasis in mammary epithelial cells and in breast tumors. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:873–884. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Azhar S, Omary MB. Keratin 8 phosphorylation by p38 kinase regulates cellular keratin filament reorganization: modulation by a keratin 1-like disease causing mutation. J Biol Chem. 2002a;277:10775–10782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Darling JM, Krams SM, Esquivel CO, Keeffe EB, Sibley RK, et al. Keratin 8 and 18 mutations are risk factors for developing liver disease of multiple etiologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003a;100:6063–6068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0936165100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Gish R, Wright TL, Omary MB. Keratin 8 mutations in patients with cryptogenic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1580–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Michie S, Oshima RG, Omary MB. Chronic hepatitis, hepatocyte fragility, and increased soluble phosphoglycokeratins in transgenic mice expressing a keratin 18 conserved arginine mutant. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1303–1314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Michie S, Resurreccion EZ, Broome RL, Omary MB. Keratin binding to 14-3-3 proteins modulates keratin filaments and hepatocyte mitotic progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002b;99:4373–4378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072624299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Omary MB. Keratins turn over by ubiquitination in a phosphorylation-modulated fashion. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:547–552. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Omary MB. A disease- and phosphorylation-related nonmechanical function for keratin 8. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:115–125. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Soetikno RM, Omary MB. Keratin mutation in transgenic mice predisposes to Fas but not TNF-induced apoptosis and massive liver injury. Hepatology. 2003b;37:1006–1014. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Strnad P, Zhong BH, Tao GZ, Omary MB. Keratins let liver live: mutations predispose to liver disease and crosslinking generates Mallory–Denk bodies. Hepatology. 2007;46:1639–1649. doi: 10.1002/hep.21976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Wright TL, Terrault NA, Gish R, Omary MB. Mutation of human keratin 18 in association with cryptogenic cirrhosis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:19–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI119127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku NO, Zhou X, Toivola DM, Omary MB. The cytoskeleton of digestive epithelia in health and disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G1108–G1137. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.6.G1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane EB, McLean WH. Keratins and skin disorders. J Pathol. 2004;204:355–366. doi: 10.1002/path.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane EB, Rugg EL, Navsaria H, Leigh IM, Heagerty AH, Ishida-Yamamoto A, et al. A mutation in the conserved helix termination peptide of keratin 5 in hereditary skin blistering. Nature. 1992;356:244–246. doi: 10.1038/356244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr HA, Folpe A, Yaziji H, Kommoss F, Gown AM. Cytokeratin 8 immunostaining pattern and E-cadherin expression distinguish lobular from ductal breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:190–196. doi: 10.1309/CPUX-KWEH-7B26-YE19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J, Ku NO, Omary MB. Stress, apoptosis, and mitosis induce phosphorylation of human keratin 8 at Ser-73 in tissues and cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17565–17573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder S, Olofsson MH, Herrmann R, Ulukaya E. Utilization of cytokeratin-based biomarkers for pharmacodynamic studies. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10:353–359. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Chen Z, Wang J, Shao X, Cui Z, Yang C, et al. Overexpression of cell surface cytokeratin 8 in multidrug-resistant MCF-7/MX cells enhances cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix. Neoplasia. 2008a;10:1275–1284. doi: 10.1593/neo.08810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Fan D, Qi J, Zhu H, Zhou Y, Yang C, et al. Co-expression of cytokeratin 8 and breast cancer resistant protein indicates a multifactorial drug-resistant phenotype in human breast cancer cell line. Life Sci. 2008b;83:496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Qian J, Singh H, Meiers I, Zhou X, Bostwick DG. Immunohistochemical analysis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, renal oncocytoma, and clear cell carcinoma: an optimal and practical panel for differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1290–1297. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-1290-IAOCRC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C, Yu QC, Cheng J, Turksen K, Degenstein L, Hutton E, et al. The basal keratin network of stratified squamous epithelia: defining K15 function in the absence of K14. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1329–1344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loranger A, Duclos S, Grenier A, Price J, Wilson-Heiner M, Baribault H. Simple epithelium keratins are required for maintenance of hepatocyte integrity. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1673–1683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magin TM, Schroder R, Leitgeb S, Wanninger F, Zatloukal K, Grund C, et al. Lessons from keratin 18 knockout mice: formation of novel keratin filaments, secondary loss of keratin 7 and accumulation of liver-specific keratin 8-positive aggregates. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1441–1451. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashukova A, Oriolo AS, Wald FA, Casanova ML, Kroger C, Magin TM, et al. Rescue of atypical protein kinase C in epithelia by the cytoskeleton and Hsp70 family chaperones. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2491–2503. doi: 10.1242/jcs.046979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matros E, Bailey G, Clancy T, Zinner M, Ashley S, Whang E, et al. Cytokeratin 20 expression identifies a subtype of pancreatic adenocarcinoma with decreased overall survival. Cancer. 2006;106:693–702. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor DK, Wu TT, Rashid A, Luthra R, Hamilton SR. Reduced expression of cytokeratin 20 in colorectal carcinomas with high levels of microsatellite instability. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:712–718. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126757.58474.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Wu Z, Yin X, Zhao Y, Chen M, Si Y, et al. Keratin 18 attenuates estrogen receptor alpha-mediated signaling by sequestering LRP16 in cytoplasm. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz KD, Demichelis F, Sboner A, Hirsch MS, Dal Cin P, Struckmann K, et al. Association of cytokeratin 7 and 19 expression with genomic stability and favorable prognosis in clear cell renal cell cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:569–576. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuuchi E, Semba S, Kodama Y, Yokozaki H, et al. Down-modulation of keratin 8 phosphorylation levels by PRL-3 contributes to colorectal carcinoma progression. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1802–1810. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll R, Divo M, Langbein L. The human keratins: biology and pathology. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129:705–733. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll R, Franke WW, Schiller DL, Geiger B, Krepler R. The catalog of human cytokeratins: patterns of expression in normal epithelia, tumors and cultured cells. Cell. 1982;31:11–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll R, Lowe A, Laufer J, Franke WW. Cytokeratin 20 in human carcinomas. A new histodiagnostic marker detected by monoclonal antibodies. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:427–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll R, Schiller DL, Franke WW. Identification of protein IT of the intestinal cytoskeleton as a novel type I cytokeratin with unusual properties and expression patterns. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:567–580. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na N, Chandel NS, Litvan J, Ridge KM. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are required for hypoxia-induced degradation of keratin intermediate filaments. FASEB J. 2010;24:799–809. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Tan TT, Rabson AB, Anderson D, Degenhardt K, White E. Hypoxia and defective apoptosis drive genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2095–2107. doi: 10.1101/gad.1204904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitakis NG, Tosios KI, Papanikolaou VS, Rivera H, Papanicolaou SI, Ioffe OB. Immunohistochemical expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in malignant salivary gland tumors. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:407–415. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermajer N, Doljak B, Kos J. Cytokeratin 8 ectoplasmic domain binds urokinase-type plasminogen activator to breast tumor cells and modulates their adhesion, growth and invasiveness. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:88. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary MB, Coulombe PA, McLean WH. Intermediate filament proteins and their associated diseases. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2087–2100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary MB, Ku NO, Liao J, Price D. Keratin modifications and solubility properties in epithelial cells and in vitro. Subcell Biochem. 1998;31:105–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary MB, Ku NO, Strnad P, Hanada S. Toward unraveling the complexity of simple epithelial keratins in human disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1794–1805. doi: 10.1172/JCI37762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary MB, Ku NO, Tao GZ, Toivola DM, Liao J. ‘Heads and tails’ of intermediate filament phosphorylation: multiple sites and functional insights. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oriolo AS, Wald FA, Ramsauer VP, Salas PJ. Intermediate filaments: a role in epithelial polarity. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2255–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters B, Kirfel J, Bussow H, Vidal M, Magin TM. Complete cytolysis and neonatal lethality in keratin 5 knockout mice reveal its fundamental role in skin integrity and in epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1775–1789. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. Science. 2009;326:1208–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.1175862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan RA, Cohlberg JA, Schiller DL, Hatzfeld M, Franke WW. Heterotypic tetramer (A2D2) complexes of non-epidermal keratins isolated from cytoskeletons of rat hepatocytes and hepatoma cells. J Mol Biol. 1984;178:365–388. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge KM, Linz L, Flitney FW, Kuczmarski ER, Chou YH, Omary MB, et al. Keratin 8 phosphorylation by protein kinase C delta regulates shear stress-mediated disassembly of keratin intermediate filaments in alveolar epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30400–30405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riopel CL, Butt I, Omary MB. Method of cell handling affects leakiness of cell surface labeling and detection of intracellular keratins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1993;26:77–87. doi: 10.1002/cm.970260108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolli CG, Seufferlein T, Kemkemer R, Spatz JP. Impact of tumor cell cytoskeleton organization on invasiveness and migration: a microchannel-based approach. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Volk C, Helmke B, Berger S, Hinz U, Koch M, et al. Expression of cytokeratin-20 in pancreatic cancer: an indicator of poor outcome after R0 resection. Surgery. 2006;139:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte B, Henfling M, Kolgen W, Bouman M, Meex S, Leers MP, et al. Keratin 8/18 breakdown and reorganization during apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2004;297:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer J, Bowden PE, Coulombe PA, Langbein L, Lane EB, Magin TM, et al. New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:169–174. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan S, DeGiulio JV, Lorand L, Goldman RD, Ridge KM. Micromechanical properties of keratin intermediate filament networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:889–894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710728105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan S, Schneider JL, Sitikov A, Goldman RD, Ridge KM. Shear stress induced reorganization of the keratin intermediate filament network requires phosphorylation by protein kinase C zeta. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2755–2765. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith F. The molecular genetics of keratin disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:347–364. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeth E, Grigoleit U, Moellmann B, Roder C, Schniewind B, Kremer B, et al. Detection of tumor cell dissemination in pancreatic ductal carcinoma patients by CK 20 RT-PCR indicates poor survival. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:669–676. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey SN, Sulem P, Masson G, Gudjonsson SA, Thorleifsson G, Jakobsdottir M, et al. New common variants affecting susceptibility to basal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:909–914. doi: 10.1038/ng.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson IM, Salvesen HB, Akslen LA. Loss of p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 expression is associated with more aggressive tumors in endometrial carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1227–1233. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert PM, Marekov LN, Parry DA. Conservation of the structure of keratin intermediate filaments: molecular mechanism by which different keratin molecules integrate into preexisting keratin intermediate filaments during differentiation. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10046–10056. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strnad P, Zhou Q, Hanada S, Lazzeroni LC, Zhong BH, So P, et al. Keratin variants predispose to acute liver failure and adverse outcome: race and ethnic associations. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:828–835. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.007. 835 e1–e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styers ML, Kowalczyk AP, Faundez V. Intermediate filaments and vesicular membrane traffic: the odd couple’s first dance? Traffic. 2005;6:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh S, Spatz J, Mills JP, Micoulet A, Dao M, Lim CT, et al. Connections between single-cell biomechanics and human disease states: gastrointestinal cancer and malaria. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Paladini RD, Coulombe PA., x Cloning and characterization of multiple human genes and cDNAs encoding highly related type II keratin 6 isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18581–18592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toivola DM, Ku NO, Resurreccion EZ, Nelson DR, Wright TL, Omary MB. Keratin 8 and 18 hyperphosphorylation is a marker of progression of human liver disease. Hepatology. 2004;40:459–466. doi: 10.1002/hep.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toivola DM, Nakamichi I, Strnad P, Michie SA, Ghori N, Harada M, et al. Keratin overexpression levels correlate with the extent of spontaneous pancreatic injury. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:882–892. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toivola DM, Strnad P, Habtezion A, Omary MB. Intermediate filaments take the heat as stress proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toivola DM, Tao GZ, Habtezion A, Liao J, Omary MB. Cellular integrity plus: organelle-related and protein-targeting functions of intermediate filaments. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:608–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toivola DM, Zhou Q, English LS, Omary MB. Type II keratins are phosphorylated on a unique motif during stress and mitosis in tissues and cultured cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1857–1870. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiber M, Schulz HU, Landt O, Drenth JP, Castellani C, Real FX, et al. Keratin 8 sequence variants in patients with pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. J Mol Med. 2006;84:1015–1022. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uenishi T, Yamazaki O, Tanaka H, Takemura S, Yamamoto T, Tanaka S, et al. Serum cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA21-1) as a prognostic factor in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:583–589. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9650-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulukaya E, Yilmaztepe A, Akgoz S, Linder S, Karadag M. The levels of caspase-cleaved cytokeratin 18 are elevated in serum from patients with lung cancer and helpful to predict the survival. Lung Cancer. 2007;56:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den IP, Norman DG, Quinlan RA. Molecular chaperones: small heat shock proteins in the limelight. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R103–R105. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Rijn M, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Haas P, Kallioniemi O, Kononen J, et al. Expression of cytokeratins 17 and 5 identifies a group of breast carcinomas with poor clinical outcome. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1991–1996. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64476-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraj P, Kroger C, Reuter U, Windoffer R, Leube RE, Magin TM. Keratins regulate protein biosynthesis through localization of GLUT1 and -3 upstream of AMP kinase and Raptor. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:175–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraj P, Sohl G, Magin TM. Keratin transgenic and knockout mice: functional analysis and validation of disease-causing mutations. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;360:203–251. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-165-7:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chan JY, Fong CC, Tzang CH, Fung KP, Yang M. Transcriptional analysis of doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity and resistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Liver Int. 2009;29:1338–1347. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weckermann D, Polzer B, Ragg T, Blana A, Schlimok G, Arnholdt H, et al. Perioperative activation of disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow of patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1549–1556. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Langbein L, Praetzel S, Jacobs M, Rogers MA, Leigh IM, et al. A novel human type II cytokeratin, K6hf, specifically expressed in the companion layer of the hair follicle. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:955–962. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelfle U, Cloos J, Sauter G, Riethdorf L, Janicke F, van Diest P et al. Molecular signature associated with bone marrow micrometastasis in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5679–5684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelfle U, Sauter G, Santjer S, Brakenhoff R, Pantel K. Down-regulated expression of cytokeratin 18 promotes progression of human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2670–2674. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woll S, Windoffer R, Leube RE. p38 MAPK-dependent shaping of the keratin cytoskeleton in cultured cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:795–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xenidis N, Ignatiadis M, Apostolaki S, Perraki M, Kalbakis K, Agelaki S et al. Cytokeratin-19 mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells after adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2177–2184. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Ibusuki M, Nakano M, Kawasoe T, Hiki R, Iwase H. Clinical significance of basal-like subtype in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2009;16:260–267. doi: 10.1007/s12282-009-0150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XR, Xu Y, Shi GM, Fan J, Zhou J, Ji Y, et al. Cytokeratin 10 and cytokeratin 19: predictive markers for poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients after curative resection. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3850–3859. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano S, Komine M, Fujimoto M, Okochi H, Tamaki K. Mechanical stretching in vitro regulates signal transduction pathways and cellular proliferation in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaziji H, Battifora H, Barry TS, Hwang HC, Bacchi CE, McIntosh MW, et al. Evaluation of 12 antibodies for distinguishing epithelioid mesothelioma from adenocarcinoma: identification of a three-antibody immunohistochemical panel with maximal sensitivity and specificity. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:514–523. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajchowski DA, Bartholdi MF, Gong Y, Webster L, Liu HL, Munishkin A, et al. Identification of gene expression profiles that predict the aggressive behavior of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5168–5178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatloukal K, French SW, Stumptner C, Strnad P, Harada M, Toivola DM, et al. From Mallory to Mallory–Denk bodies: what, how and why? Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2033–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]