Abstract

The acute and chronic effects of certain drugs can often be opposite. For example, in congestive heart failure acute administration of β-adrenoceptor agonists results in a beneficial improvement in symptoms of the disease, but their chronic use increases mortality. Conversely, certain β-adrenoceptor antagonists/inverse agonists (β-blockers) initially cause a detrimental response by decreasing cardiac contractility in congestive heart failure, while chronic treatment with the same β-blockers improves contractility and survival. Furthermore, this time-dependent reversal of outcomes occurs in non-pharmacologic interventions such as exercise and can even be observed in the response of plants to pruning or other stressors with the results being a different short-term versus long-term effect. Here we review some of these phenomena with a special emphasis on the temporal dissociation of pharmacological effects. While Francis Colpaert used this knowledge to lead a drug discovery project for an analgesic compound that initially produced hyperalgesia, we will focus on examples outside the central nervous system (CNS).

Keywords: Asthma, Congestive Heart Failure, Paradoxical Pharmacology, β-blockers, Francis Colpaert

Prologue

Given that this Special Issue is dedicated to the life and work of Francis Colpaert, we include a brief description of our personal experience with Francis the scientist, and more importantly, Francis the man.

In 2002, Adrian Newman-Tancredi and we were attending a conference on inverse agonism in S’Agaro Spain. After Adrian heard my talk on the counterintuitive use of β-adrenoceptor inverse agonists (a subset of β-blockers), he approached me and said that I should contact his boss, Francis Colpaert. Adrian said Francis was also thinking counterintuitively and was even applying it to drug discovery. Francis and I began a very enjoyable extensive email discussion on paradox – with the discussion often turning into philosophical arguments. As a result of these emails, about a year later Francis decided to stop by and meet with us in Houston on his way to San Antonio. We spent a lovely couple of days and it very much cemented our friendship, likely due to our love for food and wine, as much as our love of paradox. Anyway, we stayed in email and phone contact for the next few years. Even when months had gone by in between contacts, it was as if we had just communicated the day before. We next saw each other at a conference in Hamburg where we were both speakers in a session appropriately titled, ‘Paradoxical Pharmacology’. Of course, we did manage among other things to fit in a nine course degustation dinner with matching wines at one of the city’s top restaurants. The following year we visited his home outside Toulouse, ‘Mirabel’, where we met Anne, his partner of 20+ years, and had an absolutely wonderful time. Francis’ constant joy of life was contagious. We stayed in email/phone contact for a few months mainly about science, but also about the ups and downs of Francis’ life in the pharmaceutical industry.

In March of last year we decided to call Francis because it had been months since we had communicated. It was then he told me about his recent diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. With help from a friend and colleague, Richard managed to get in touch with the Head of GI oncology (Jim Abbruzzese) at arguably the world’s best cancer institute, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas. Jim was absolutely wonderful, and even though he advised that Francis not make the trip to MD Anderson, he would always offer support and treatment options and regimens for Francis to discuss with his oncologists. We returned to Mirabel in July and Francis looked a bit thinner, but still full of life when he wasn’t exhausted. By this time we knew Francis’ first treatment regimen had failed to stop the tumor growth or metastasis. Jim Abbruzzese then recommended a regimen that included a drug approved in Europe for some cancers but still in clinical trials for pancreatic cancer and not available in France. Heather managed to get the company to review Francis’ case and agree to provide Francis with the drug. While no drug yet discovered is very effective in this disease, it did provide hope. We went back to Mirabel 7 weeks later and now Francis did look very poorly but still his agile brain and lovely smile provided us all with much to enjoy during that last visit. It was distressing that the French system was so slow in obtaining the drug. The drug finally arrived about two weeks later (2 months after the company offered to provide it.) Ironically, it arrived the day Francis died.

While all of the last 8 months of his life seemed filled with sad and tragic events, Francis remained as full of life as possible – indeed to me it often seemed miraculous that he could enjoy so much the times when he was alert enough to engage in discussions, or when he was hungry enough to have something substantial to eat. Francis’ joy of life was simply incredible, and that is what we remember. A life too short but filled with enough passion to fuel all who knew him. It is a true privilege to have had him as a friend.

Introduction

The observation that certain drugs require time to produce an effect, or that certain drugs lose effectiveness with time, is well established. The oldest example of this latter phenomenon is likely the thousands of years old observation that the analgesic effect of opioids wane with repeated administration for weeks or months. In general we term this observation tolerance, or tachyphylaxis or desensitization. However in receptor pharmacology the term desensitization is most often used to signify either a loss of ability of the receptor to couple to its effector machinery, or a loss of receptor numbers by either sequestration or degradation. With few exceptions, this loss of responsiveness is viewed as a detrimental property of prolonged drug treatment with an agonist. Francis Colpaert turned this idea on its head by hypothesizing that perhaps if we administered high efficacy agonists to a receptor that mediated a hyperalgesic effect, then desensitization of this system would lead to an analgesic effect. Indeed this is the proposed mechanism of action of the high efficacy serotonin 5-HT1A agonist, F-13640 (Bardin et al., 2005, Bardin and Colpaert, 2004)

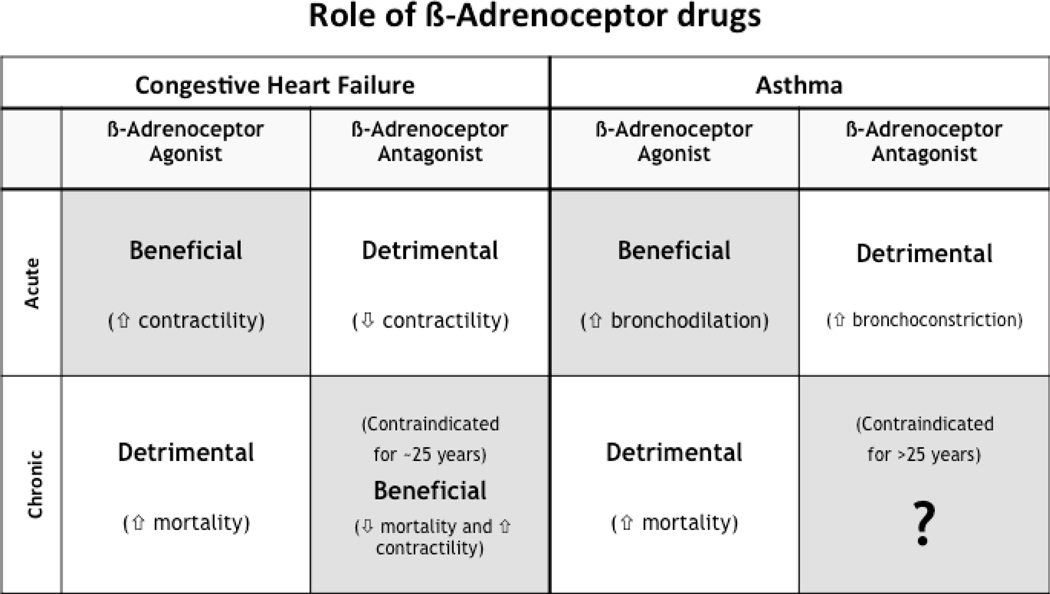

As stated above, while we will very briefly discuss examples of what might be termed ‘paradoxical pharmacology’ produced by drugs acting in the central nervous system (CNS), we will focus on two apparently unrelated diseases of the periphery – congestive heart failure (CHF), and asthma. These diseases may appear dissimilar, but in both conditions β-adrenoceptor agonists are acutely beneficial, but chronically detrimental. Conversely, the acute use of β-adrenoceptor inverse agonists (a subset of ‘β-blockers’ capable of not only blocking agonist induced receptor activation, but also inhibiting constitutive signaling by unoccupied β-adrenoceptors) is detrimental, but their chronic use has been proven to be beneficial in the treatment of CHF (Bristow, 2000, Hall et al. , 1995, Krum et al., 1995, Lechat et al., 1998), and recent reports suggest the same may be true in the treatment of asthma (Callaerts-Vegh et al., 2004, Hanania et al., 2010b, 2008, Lin et al., 2008, Nguyen et al., 2008, 2009; see also Bond, 2001, 2002, Bond et al., 2007, Dickey et al., 2010, Hanania et al., 2010a, Parra and Bond, 2007, Walker et al., 2010).

Congestive heart failure

CHF is a disease of impaired cardiac contractility usually as a result of ischemic damage to the heart muscle. The body’s response to the resultant decrease in cardiac output is to try and ‘compensate’ by activating the sympathetic nervous system and the rennin-angiotensin system in order to increase cardiac output and circulating blood volume. Because activation of these systems leads to a compensatory increase in cardiac output, initial drug development strategies were based on further enhancing cardiac output with the use of β-adrenoceptor agonists to increase cardiac contractility. However, clinical trials demonstrated that while the acute use of β adrenoceptor agonist in CHF was associated with improved hemodynamics and decreased symptoms of CHF, prolonged administration of βAR agonists resulted in an increase in mortality (1990, Weber et al., 1982). However, perhaps a more unexpected finding was that when administered chronically, certain β-blockers were shown to increase cardiac contractility and decrease mortality in CHF (Bristow, 2000, Hall et al., 1995, Krum et al., 1995, Lechat et al., 1998). This was a truly remarkable reversal – chronic administration of acutely negative inotropic drugs, like the β-blockers/inverse agonists carvedilol or metoprolol, resulted in an increase in cardiac contractility and a decrease in mortality in CHF with chronic use. Thus, for what we believe to be the only time ever in pharmacological history, certain members of a class of drugs have moved from being contraindicated to drugs of choice in the disease for which they were contraindicated (figure 1, left panel).

Figure 1.

A schematic of the different effects produced by the acute and chronic use of agonists and antagonists in congestive heart failure and asthma. (Modified from Bond 2001).

Asthma

“The universe is filled with things that happen once, but if it happens twice, it will happen a third time.” Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist.

So was the total reversal in the chronic management of CHF an isolated event, or an example of a more general principle? If one decides to answer that question, the disease that comes up as a logical choice is asthma (Figure 1). Just as in CHF, the use of β-adrenoceptor agonists (in this case agonists of the beta2-adrenoceptor subtype) is beneficial. β2-adrenoceptor agonists are the most potent bronchodilators discovered and are an important component of the treatment regimen of all asthmatics, regardless of disease severity. However, their constant chronic use has been associated with detrimental effects ranging from loss of bronchoprotection to increases in asthma-related deaths (Bond et al., 2007, Nelson et al., 2006), sufficient to cause the FDA to mandate severe restrictions in their use in asthmatics. Also, just as was the case in CHF, β-adrenoceptor antagonists/inverse agonists are contraindicated in patients with asthma. Therefore in asthma the outcomes of using agonists acutely or chronically, or using antagonists acutely had shown a perfect correlation to CHF (Figure 1). However, the effect of chronic use of beta-blockers, had never been tested (Bond, 2001, 2002).

Our laboratory decided to test the hypothesis that chronic use of certain beta-blockers may be beneficial in asthma management. Now a decade after the initial experiments were run, and with the help of collaborators, we have provided considerable evidence, including two small (10 patients) studies in mild asthmatics (Hanania et al., 2008, 2010b), that chronic treatment with β-blockers/inverse agonists may result in positive outcomes in asthmatics, as would be predicted from the CHF experience (Bristow, 2000, Hall et al., 1995, Krum et al., 1995, Lechat et al., 1998). For those interested in further reading, all of the data in support of the use of chronic β-adrenoceptor inverse agonists has recently been reviewed and potential mechanisms have been postulated (Dickey et al., 2010, Walker et al., 2010)

Brief examples from treatment of CNS diseases

The CNS does have several examples of therapies that either appear paradoxical, or have an opposite effect, dependent on duration of treatment. For example, the CNS stimulant methylphenidate is used in the treatment of hyperactivity disorders. Additional examples include the loss of analgesia with the chronic, constant use of opioids and, conversely, the production of analgesia by use of a serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist. Stimulation of this receptor can initially mediate hyperalgesia but Francis Colpaert discovered that chronic use of the high efficacy 5-HT1A agonist, F-13640, results in profound and persistent analgesia. He speculated that the agonist had induced long-term neuro-adaptive changes in the 5-HT1A receptor (Colpaert, 2006, Deseure et al., 2007). There are also other examples where desensitization has been hypothesized to be a mechanism of action for the beneficial effect of the drug, but the finding tends to be discovered retrospectively and not by deliberate drug design. For example, the delay in the therapeutic effect of anti-depressants that block uptake of neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinehrine (NE) has been hypothesized to be a consequence of the need to produce desensitization of some of the receptor subtypes for these neurotransmitters.

A further example of how duration of agonist administration can determine its effect, and consequently the disease for which it is indicated is gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). Pulsatile administration of GnRH is used to simulate physiological signaling of the GnRH receptor and can restore reproductive potential to men and women whose infertility is a result of anomalous endogenous GnRH production or release. On the other hand, if GnRH is administered constantly via a depot injection or by using synthetic long-acting GnRH agonists, this chronic stimulation of the GnRH receptor results in GnRH receptor desensitization and loss of response from the reproductive hormone axis (Beyer et al., 2011, Oliveira et al., 2010).

Non-pharmacologic examples of short-term detrimental behaviors for a longer-term benefit – ‘no pain, no gain’

Behaviors like exercise also have opposing physiological effects (i.e., on muscle tissue) between a single acute event, and repetitive chronic exercise. Other behaviors also use strategies that are detrimental in the short-term, in order to derive a long-term beneficial effects. Examples of these behaviors include dieting, saving money, and disciplining children. Even with plants, the effects of pruning (a ‘treatment’) are different between the short and long term results.

We in fact speculate that acceptance of the rule of ‘do no harm’ may be doing medicine and drug discovery a disservice. This disservice is most likely to occur in cases where decisions are made to discontinue a drug discovery project on the basis of negative or ‘harmful’ results of an acute experiment, when the project was aimed at treatment for a chronic disease or condition. The current model of drug discovery is in itself paradoxical. Most diseases targeted by the pharmaceutical industry are those for which regular, long-term treatment is required. However, the constant pressure for speed, efficiency and cost-effectiveness in the drug discovery process means that decisions to halt or progress projects are often based upon the results of short-term experiments.

Conclusions

"Paradox is truth standing on her head to attract attention." G. K. Chesterton

The identification of the phenomena of temporal differences in the effects of both agonists and antagonists in numerous drug classes has, at first observation, seemed extremely paradoxical. However, as scientists, our natural inclination is to ask the question ‘why?’. Over the coming years the mechanistic basis for such behavior will undoubtedly be revealed, and the paradox will be no more. An excellent example of this is perhaps the first and most studied example of a paradoxical approach in medicine – the use of vaccines. Clearly injecting even attenuated pathogens as a preventative measure for a disease is somewhat counterintuitive, and can certainly result in short-term discomfort for a longer-term gain, but immunology has now clearly explained why the phenomena works and it no longer even appears to us as paradoxical. Nevertheless for those of us, like Francis Colpaert, who have felt compelled to challenge dogma of current treatment paradigms because we observed paradoxical behavior, the path has been long and challenging. Seemingly ‘simple’ explanations of mechanism of action of a particular drug class become turned on their head, and obtaining funding, and acceptance of paradigm-shifting ideas by peers, takes many years. For example, it took over 20 years from the first study indicating the utility of beta-blockers in CHF to the first marketing approval for such an indication. As Sir James Black would remind us, “it took 18 months to create the dogma (of β-blockers being contraindicated in CHF), and over two decades to reverse it”. It was the challenge of the paradox that fascinated Francis, and his curiosity, insightful science and perseverance have resulted in a potential new treatment for pain: a fitting legacy from this special man.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Bhupinder Singh for his help and input in producing this manuscript. Some of the ideas contained in this manuscript have been supported by the National Institutes of Health (RAB); the American Asthma Foundation (RAB); and Inverseon® Inc., (RAB and HG).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential conflict of interest: RAB and HG are shareholders in Inverseon® Inc.

References

- Bardin L, Assie MB, Pelissou M, Royer-Urios I, Newman-Tancredi A, Ribet JP, et al. Dual, hyperalgesic, and analgesic effects of the high-efficacy 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A (5-HT1A) agonist F 13640 [(3-chloro-4-fluoro-phenyl)-[4-fluoro-4-{[(5-methyl-pyridin-2-ylmethyl)-amino]-methyl}piperidin-1-yl]methanone, fumaric acid salt]: relationship with 5-HT1A receptor occupancy and kinetic parameters. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:1034–1042. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.077669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin L, Colpaert FC. Role of spinal 5-HT(1A) receptors in morphine analgesia and tolerance in rats. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer DA, Amari F, Thill M, Schultze-Mosgau A, Al-Hasani S, Diedrich K, et al. Emerging gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2011 doi: 10.1517/14728214.2010.547472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond RA. Is paradoxical pharmacology a strategy worth pursuing? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:273–276. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01711-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond RA. Can intellectualism stifle scientific discovery? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:825–829. doi: 10.1038/nrd918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond RA, Spina D, Parra S, Page CP. Getting to the heart of asthma: can "beta blockers" be useful to treat asthma? Pharmacol Ther. 2007;115:360–374. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow MR. beta-adrenergic receptor blockade in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:558–569. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.5.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaerts-Vegh Z, Evans KL, Dudekula N, Cuba D, Knoll BJ, Callaerts PF, et al. Effects of acute and chronic administration of beta-adrenoceptor ligands on airway function in a murine model of asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4948–4953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400452101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC. 5-HT(1A) receptor activation: new molecular and neuroadaptive mechanisms of pain relief. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;7:40–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deseure K, Breand S, Colpaert FC. Curative-like analgesia in a neuropathic pain model: parametric analysis of the dose and the duration of treatment with a high-efficacy 5-HT(1A) receptor agonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;568:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey BF, Walker JK, Hanania NA, Bond RA. beta-Adrenoceptor inverse agonists in asthma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SA, Cigarroa CG, Marcoux L, Risser RC, Grayburn PA, Eichhorn EJ. Time course of improvement in left ventricular function, mass and geometry in patients with congestive heart failure treated with beta-adrenergic blockade. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1154–1161. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00543-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanania NA, Singh S, El-Wali R, Flashner M, Franklin AE, Garner WJ, et al. The safety and effects of the beta-blocker, nadolol, in mild asthma: an open-label pilot study. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanania NA, Dickey BF, Bond RA. Clinical implications of the intrinsic efficacy of beta-adrenoceptor drugs in asthma: full, partial and inverse agonism. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010a;16:1–5. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328333def8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanania NA, Mannava B, Franklin AE, Lipworth BJ, Williamson PA, Garner WJ, et al. Response to salbutamol in patients with mild asthma treated with nadolol. Eur Respir J. 2010b;36:963–965. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00003210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krum H, Sackner-Bernstein JD, Goldsmith RL, Kukin ML, Schwartz B, Penn J, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the long-term efficacy of carvedilol in patients with severe chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1995;92:1499–1506. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.6.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechat P, Packer M, Chalon S, Cucherat M, Arab T, Boissel JP. Clinical effects of beta-adrenergic blockade in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials. Circulation. 1998;98:1184–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.12.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Peng H, Nguyen LP, Dudekula NB, Shardonofsky F, Knoll BJ, et al. Changes in beta 2-adrenoceptor and other signaling proteins produced by chronic administration of 'beta-blockers' in a murine asthma model. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Dorinsky PM. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest. 2006;129:15–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LP, Omoluabi O, Parra S, Frieske JM, Clement C, Ammar-Aouchiche Z, et al. Chronic exposure to beta-blockers attenuates inflammation and mucin content in a murine asthma model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:256–262. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0279RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LP, Lin R, Parra S, Omoluabi O, Hanania NA, Tuvim MJ, et al. Beta2-adrenoceptor signaling is required for the development of an asthma phenotype in a murine model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2435–2440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810902106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira JB, Baruffi R, Petersen CG, Mauri AL, Cavagna M, Franco JG., Jr Administration of single-dose GnRH agonist in the luteal phase in ICSI cycles: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:107. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra S, Bond RA. Inverse agonism: from curiosity to accepted dogma, but is it clinically relevant? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JK, Penn RB, Hanania NA, Dickey BF, Bond RA. New perspectives regarding ss2-adrenoceptor ligands in the treatment of asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber KT, Andrews V, Janicki JS. Cardiotonic agents in the management of chronic cardiac failure. Am Heart J. 1982;103:639–649. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]