Abstract

Background

In patients with cardiogenic shock (CS) complicating an acute myocardial infarction, a strategy of emergency revascularization vs. initial medical stabilization improves survival. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABC) provides hemodynamic support and facilitates coronary angiography and revascularization in CS patients.

Methods and Results

We evaluated 499 patients with record of systemic hypoperfusion status, as an early response to IABC from the SHOCK Trial (n=185) and Registry (n=314) to determine the association between rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion following 30 minutes of IABC(CRH)and 30-day and 1-year mortality. CRH was highly associated with lower 30-day mortality (45% vs. 78%, p<0.001) in all patients. In the SHOCK Trial, among patients assigned to ERV vs. IMS, 30-day mortality was 26% vs. 29% with CRH, and 61% vs. 81% respectively without CRH, after commencing IABC. The corresponding 1-year mortality rates were 35% vs. 52% for ERV and 69% vs. 87% for IMS (interaction p ≥ 0.25 at both time points). After adjusting for important correlates of outcome (LV ejection fraction, age, and randomization to ERV) a significant association remained between CRH and 30-day mortality (odds ratio 0.18; 95% CI 0.08–0.42, p<0.001) and 1-year mortality (odds ratio 0.28; 95% CI 0.12–0.67, p<0.001).

Conclusions

In CS patients, CRH after commencing IABC was independently associated with improved 30-day and 1-year survival regardless of emergency revascularization. In CS patients, CRH with IABC is an important early prognostic feature.

Keywords: cardiogenic shock, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation, systemic hypoperfusion, survival

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is the leading cause of in-hospital death following an acute myocardial infarction (MI), and its incidence remains constant despite recent advances in the treatment of patients with an acute MI (1). In the SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK? (SHOCK) Trial, emergency revascularization compared with a strategy of initial medical stabilization significantly improved long-term survival in patients with CS complicating an acute MI (2).

In patients with CS due to predominant left ventricular (LV) failure, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABC) can improve the balance between myocardial oxygen demand and supply by reducing LV after load and augmenting diastolic coronary blood flow(3,4). In subgroup analyses of large ST-elevation MI studies, patients presenting with CS who received IABC as adjunctive therapy to fibrinolysis had better 30-day survival than those who received fibrinolytic therapy alone (5,6).

The SHOCK Trial and Registry findings have led to adoption of early mechanical revascularization as the optimal strategy of treatment for CS complicating MI. Whether the physiological response to IABC is associated with the survival of CS patients independent of mechanical revascularization is unknown.

In this report utilizing prospective, concurrent data from the multi-center SHOCK Trial and the SHOCK Trial Registry (7), we determined the relationship between rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion (CRH) with IABC and mortality. Secondly, we sought to identify clinical, hemodynamic, and coronary angiographic correlates of CRH with IABC. Thirdly, we explored the relationship between CRH with IABC and ERV on short-term and one-year mortality. We hypothesized that patients who experienced CRH represent those with greater myocardial reserve, and that these patients would derive the greatest benefit following emergency revascularization. Finally, we evaluated the incidence of IABC-related adverse events and its impact on short-term survival in patients with CS complicating an acute MI.

Methods

This analysis consisted of a cohort of patients from the SHOCK Trial and SHOCK Registry. Details of the SHOCK Trial and Registry design (8) and the definitions used have been previously published in the overall findings of the SHOCK Trial and Registry (2,7). Briefly, the SHOCK Trial was a 302-patient randomized trial comparing a strategy of emergent revascularization to initial medical stabilization in patients presenting with CS complicating an acute MI. Eligible patients had ST-segment elevation, a Q-wave infarction, a new left bundle branch block, or a posterior infarction with anterior ST segment depression complicated by shock due to predominant LV failure. In patients assigned to emergency revascularization, mechanical revascularization was attempted within 6 hours of randomization (within 18 hours of CS onset), and delayed revascularization (≥54h post-randomization) was permitted in patients assigned to initial medical stabilization. The protocol recommended the use of IABC in both treatment groups. All survivors were followed for a minimum of 1-year post-randomization.

The SHOCK Registry comprised those 1189 patients with suspected CS who did not meet all SHOCK Trial eligibility criteria or who were trial-eligible but not randomized. For all Registry patients, management decisions were made by the local physician.

Our sample consisted of 499 patients from the SHOCK Trial (n=185) and the SHOCK Registry (n=314) who had CS predominantly due to LV failure, treated with IABC and had clinical response to IABC recorded. Patients were excluded from this analysis if CS was secondary to any of the following: acute severe mitral regurgitation, ventricular septal rupture, tamponade, isolated right ventricular shock, prior severe valvular heart disease, excess beta or calcium channel blockade, or a cardiac catheterization procedural complication.

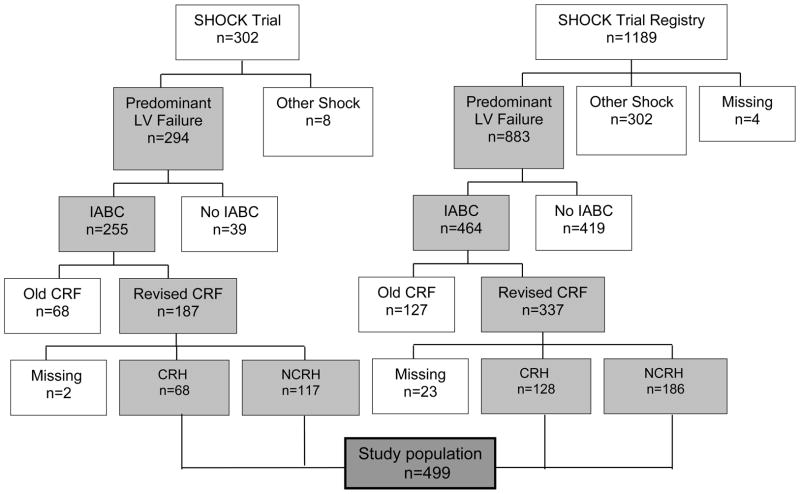

For the purposes of our analysis, patients were categorized as having either rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion (CRH), or no CRH (NCRH). We defined CRH as reversal of extremity hypoperfusion or improvement in mentation, within 30 minutes of 1:1 augmentation with IABC. The early response to IABC on systemic hypoperfusion was recorded prospectively on modified case report forms (CRF) available after enrollment in the SHOCK Trial and Registry (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The method of patient selection for analysis. SHOCK = SHould we revascularize Occluded Coronaries in cardiogenic shocK?; LV = left ventricular; IABC = intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation; CRF = case report forms; CRH = complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; NCRH = non-complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion.

Centrally-trained study coordinators completed CRF using abstracted data from patient records in both Trial and Registry patients. The CRF captured patient and infarct characteristics, hemodynamic measures, procedure-use data, complications, local discharge diagnoses (ICD-9 codes), and vital status at discharge. Vital status at 1-year was determined by telephone follow-up.

In the SHOCK Trial, each patient’s quantitative assessment of LV function and coronary artery disease (CAD) severity was made by trained core angiography laboratory staff members blinded to patient clinical details, treatment assignment and outcome (6,8). Severe bleeding was defined as a >15% absolute reduction in hematocrit, and the probable site of blood loss was recorded. Acute renal failure was diagnosed if a rise in creatinine>3.0 mg/dl occurred after initial normal presentation. The timing of other IABC-related complications and the treatment modality for treating vascular complications because of IABC were prospectively recorded on the CRF.

SHOCK Registry angiographic data were centrally abstracted from the local cardiac catheterization report. Unlike the SHOCK Trial, hemodynamics 6-hours post randomization and quantitative CAD anatomy assessment were not recorded, and vital status was available at hospital discharge only.

The SHOCK Trial and Registry and creation of the manuscript were supported by grants from the NHLBI (RO1-HL 50020 and HL 49970, 1994–99, Bethesda, Maryland). The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analysis and drafting and editing of this manuscript.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics are presented as means ± standard deviation (median and quartiles for skewed variables) for continuous data, or as percentages for categorical data. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. CRH and NCRH differences in baseline patient, hemodynamic, and angiographic characteristics were compared using Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Thirty-day and 1-year mortality were analyzed by multivariable logistic regression, with adjustment for factors known to be correlates of outcome and/or differing between the CRH and NCRH groups. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to demonstrate the survival differences. A propensity score adjustment was also performed for the combined trial and registry cohort. The score was obtained from the logistic regression predicted probability of CRH, using 11 variables that differed at the .20 level between CRH and NCRH. This adjustment was incorporated into the logistic regression model for 30-day mortality. Analyses were conducted with Statistical Analysis System (Cary, NC, version 8.2) and S-Plus (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA, version 6.0.3) software.

Results

Overall cohort

Of the 499 patients eligible for this analysis, CRH occurred in 196 patients (39%), with similar proportions of CRH occurring in the SHOCK Trial (37%) and Registry (41%) patients (p=0.394). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients with CRH and NCRH. The groups were similar in terms of important clinical variables and index MI characteristics, though patients with CRH had a 4-percentage-point higher mean LV ejection fraction (EF)(p=0.005), and more often had prior angioplasty (p=0.036).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by response to IABC

| CRH n = 196 |

NCRH n = 303 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.7 ± 10.5 | 64.6 ± 11.1 | 0.475 |

| Male sex (%) | 62.8 | 70.6 | 0.078 |

| Transfer admission (%) | 52.0 | 57.8 | 0.231 |

| Hypertension (%) | 53.1 | 46.7 | 0.192 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 32.8 | 32.0 | 0.844 |

| Cigarette smoker (%) [n=426] | 59.6 | 54.0 | 0.277 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) [n=359] | 39.5 | 45.8 | 0.279 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) [n= 456] | 12.6 | 14.6 | 0.582 |

| Prior myocardial infarction (%) | 33.7 | 35.0 | 0.771 |

| Prior angioplasty (%) | 10.9 | 5.5 | 0.036 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass grafting (%) | 8.7 | 9.0 | 1.0 |

| Median initial creatinine (mg/dL) [n= 489] | 1.3 (1.1–1.8) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.052 |

| Fibrinolytic therapy use (%) | 45.4 | 38.6 | 0.137 |

| Median highest creatine kinase (IU/L) | 3068 (1461 – 5320) | 2376 (942 – 4449) | 0.095 |

| Anterior index MI (%) | 58.9 | 62.2 | 0.501 |

| Lowest systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 68.7± 14.4 | 66.5±15.5 | 0.069 |

| § Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) [n=320] | 31.0±12.4 | 27.0 ± 11.4 | 0.005 |

| Median time from MI to shock (hr) | 5.3 (2.3 –17.8) | 4.4 (1.5 –18.3) | 0.326 |

| Median time from shock to IABC (hr) | 2.7 (1.1 – 6.3) | 3.3 (1.5 – 7.1) | 0.126 |

| Revascularization pre discharge (%) | 67.9 | 63.4 | 0.337 |

| * Randomization to emergency revascularization (%) [n=185] | 33.8 | 59.8 | <0.001 |

SHOCK Trial patients only.

Recorded at any time of admission.

CRH = complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; NCRH = non-complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; IABC = intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted. Values in parentheses denote the inter-quartile range.

Baseline hemodynamic variables were measured with IABC in 52% of CRH and 40% of NCRH patients (p=0.128). There were small but significant differences between these groups in right atrial pressure, cardiac index, and cardiac power index recorded on support measures close to the time of CS diagnosis (Table 2); other hemodynamic variables were similarly distributed between the two groups.

Table 2.

Hemodynamics at shock diagnosis by response to IABC*

| CRH n = 196 |

NCRH n = 303 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | 97 ± 24 | 100 ± 25 | 0.247 |

| Right atrial pressure (mmHg) | 14.1 ± 9.0 | 16.0 ± 8.2 | 0.009 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 24.1 ± 8.2 | 24.9 ± 8.4 | 0.461 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 2.05 ± 0.72 | 1.92 ± 0.82 | 0.015 |

| CPO index (Watts/m2) | 0.32 ± 0.15 | 0.28 ± 0.14 | 0.015 |

| SVR (dynes/sec/cm−5) | 1282 ± 593 | 1268 ± 586 | 0.857 |

All measurements made while patients were on vasopressors/inotropes. Measurements expressed as means with standard deviations.

CRH = complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; NCRH = non-complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; PCWP = pulmonary-capillary wedge pressure; CPO cardiac power output index (W/m2) = (cardiac output × mean arterial pressure × constant)/body surface area; SVR = systemic vascular resistance.

The median time from CS diagnosis to IABC initiation was similar for CRH and NCRH patients (median 2.7h vs. 3.3h, p=0.126)(Table 1). IABC was initiated early (<2 hours after CS diagnosis) in approximately 31% and significantly delayed (>12 hours after CS diagnosis) in 12% in both groups. The median duration of IABC was significantly shorter in NCRH patients than in CRH patients (46.5h [interquartile range (IQR) 12.8, 87.1] vs. 56.2h [38.6, 96.5], p <0.001), due to more deaths occurring within 48-hours of shock onset in patients with NCRH (34.3% vs. 8.2%, p<0.001).

The peak and end-diastolic blood pressure (BP) increased with IABC using 1:1 augmentation (Table 3). The patients having CRH had higher pre-IABC vasopressor-supported systolic BP, a greater peak BP response to IABC, and were more likely to have a reduction in vasopressor therapy compared with NCRH patients, all consistent with the clinical diagnosis of rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion. Among the NCRH patients, 71% had improvement in BP, defined by a higher augmented peak pressure compared with pre-IABC systolic pressure, consistent with a partial response.

Table 3.

Changes in blood pressure 10–30 minutes following 1:1 augmentation with IABC by response to IABC*

| CRH n = 196 |

NCRH n = 303 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-IABC systolic BP (mmHg) | 87.8 ± 20.4 | 82.7 ± 21.7 | 0.010 |

| Pre-IABC diastolic BP (mmHg) | 54.5 ± 15.2 | 51.8 ± 16.6 | 0.087 |

| Change in augmented peak pressure (mmHg) | 23.8 ± 24.6 (p<0.001) | 13.5 ± 26 (p<0.001) | <0.001 |

| Change in augmented end diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 7.8 ± 19.0 (p<0.001) | 4.6 ± 20.7 (p=0.002) | 0.120 |

| Vasopressor support reduced post-IABC (%) | 50.0 | 14.3 | <0.001 |

All measures made while patients were on vasopressors/inotropes. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Change is defined as the 10–30 mins post-IABC with 1:1 augmentation BP minus pre-IABC BP. P-values in parenthesis denote whether change in BP is different from zero.

CRH = complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; NCRH = non-complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; IABC = intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation; BP = blood pressure.

Patients with CRH had significantly lower 30-day mortality than did NCRH patients (65% vs. 29%, p<0.001). This difference remained highly significant even after adjustment for three important variables associated with outcome (age, LVEF, and timing of revascularization), with an odds ratio for 30-day mortality of 0.26 for CRH vs. NCRH (95% CI 0.14–0.48, p<0.001) (Table 4). To confirm that confounders were not responsible for the apparent protective effect of CRH on mortality, we also constructed a propensity score using 11 variables that differed qualitatively between the CRH and NCRH groups. When the propensity score adjustment was used in the logistic regression model, the odds ratio for 30-day mortality remained highly significant, 0.21 (95% CI 0.10, 0.45, n=164, p<.0001).

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios for mortality with CRH: Survival benefit with CRH with IABC following adjustment for important correlates of outcome (LVEF, age and timing of revascularization)

| Odds Ratio CRH vs. NCRH | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHOCK Trial and Registry* | |||

| 30-day (n=227) | 0.26 | 0.14 – 0.48 | <0.001 |

| SHOCK Trial only† | |||

| 30-day (n=141) | 0.17 | 0.07 – 0.41 | <0.001 |

| 1-year (n=140) | 0.27 | 0.12 – 0.62 | 0.002 |

CRH = complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; NCRH = non-complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction;

This model was also fit using propensity score adjustment in addition to including age, LVEF and timing of revascularization in the mortality model. The covariate- and propensity score-adjusted odds ratio for CRH vs. NCRH was 0.21, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.45, p<.0001.

Timing of revascularization was defined as Early (<18 hours from shock to revascularization) vs. No/late revascularization for the combined Trial and Registry cohort. Adjustment for timing of revascularization was according to randomization assignment in the models restricted to the Trial cohort

SHOCK Trial Patients

The rate of IABC was significantly higher in the SHOCK Trial, where IABC was recommended per protocol, than in the SHOCK Registry (86.7% vs. 52.5%, p<0.001). Among SHOCK Trial patients (n=185), measurements recorded six hours post-randomization demonstrated that systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was lower in patients with CRH compared with NCRH patients (1022 ± 482 dynes/sec/cm−5 vs. 1258 ± 602 dynes/sec/cm−5, p=0.037), despite these patients having similar mean values pre-IABC (Table 2). This reduction in SVR is likely to be due to vasopressor dose reduction in patients with CRH (Table 3). In 17% of patients (n=31), hemodynamic data was unavailable at 6 hours, mainly due to death (n=18). Coronary angiography results were available in 159 (86%) patients. The prevalence of multivessel coronary artery disease was similar for CRH and NCRH (93.1% vs. 87.4%, p=0.293). The burden of coronary artery disease assessed by the Duke Jeopardy Score (9) (maximum score=12) was lower in patients with CRH compared to NCRH patients (median = 8.0 [IQR 4.0–10.0] vs. 10.0 [IQR 6.0–10.0], p=0.042)

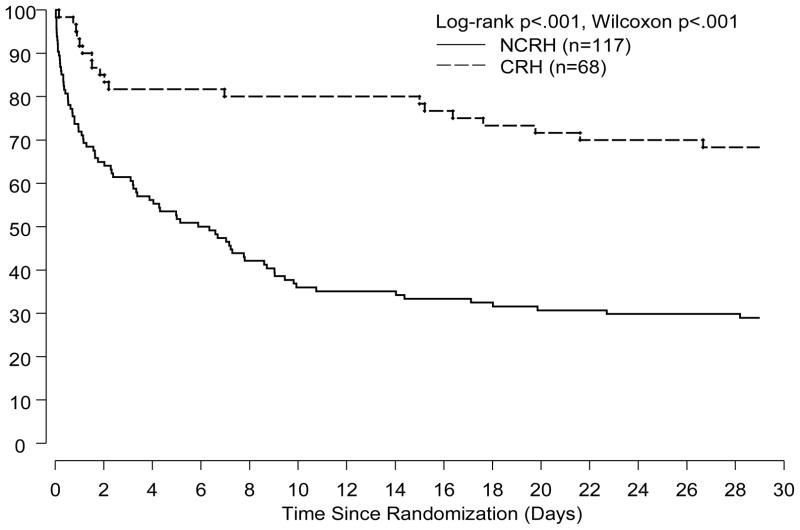

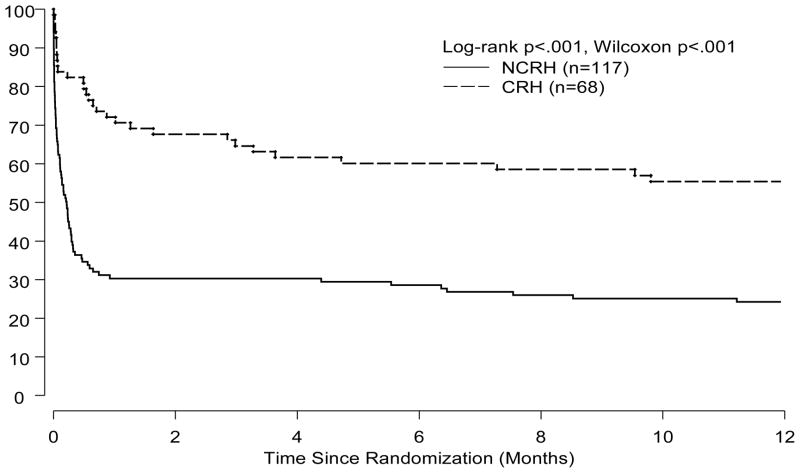

Trial patients with CRH had a significantly lower 30-day mortality rate than did NCRH patients (25% vs. 63%, p<0.001, Figure 2). These findings of a lower mortality rate amongst CRH patients were also present at 1-year (24% vs. 55%, p<0.001, Figure 3). The reduction in mortality amongst CRH patients was independent of treatment allocation and remained significant at 30-days and 1-year after adjustment for three important correlates of outcome in CS patients (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Kapan-Meier estimates of 30-day survival by response to IABC in the SHOCK Trial.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of 1-year survival by response to IABC in the SHOCK Trial.

There was a difference in the randomized strategy allocation between CRH and NCRH patients. A higher proportion of initial medical stabilization patients were represented in those with CRH compared to NCRH patients (66% vs. 40%, p<0.001). This disproportionate distribution could potentially have influenced the primary outcome, 30-day mortality, of the SHOCK Trial. When logistic regression models were used to adjust for this imbalance, emergency revascularization patients indeed had a significant 30-day survival benefit (p=0.03) with an OR of 0.43 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.93).

Adverse effects occurring in patients possibly as a result of IABC use consisted of severe hemorrhage (32%), acute renal failure (18%) and vascular access occlusion in the pertinent limb (10%). The occurrence of severe bleeding related to access site or peripheral vascular occlusions in IABC patients was not associated with higher 30-day mortality than in IABC patients without complications (p=0.129).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the immediate hemodynamic and clinical response to IABC and its relationship to mortality. In patients with CS due to LV failure, rapid complete reversal of systemic hyperperfusion following IABC is associated with marked reduction in both 30-day and 1-year mortality. The mortality reduction with CRH is independent of baseline characteristics, hemodynamic, index MI and angiographic characteristics, and had no significant interaction with the beneficial effects of emergency revascularization in CS patients. Higher baseline systolic blood pressure, better LVEF, and lower angiographic coronary artery disease burden were associated with CRH but were poorly predictive.

Evidence for or against IABC conferring survival benefit is currently based on small studies (10,11), observations from subgroup analyses (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries[GUSTO] I/III)(12), and community registries (13). Despite the absence of data from large randomized clinical trials, substantial evidence supports the use of IABC in CS patients. Similarly, data from other registries (5) and SHOCK Registry (6) have suggested lower mortality with the use of fibrinolysis in conjunction with IABC in CS patients compared to fibrinolysis alone. The benefits of IABC as adjunctive therapy are independent of any differences in baseline characteristics. Prior attempts to ascertain the treatment effect of IABC through clinical trials in high-risk acute MI patients have been unsuccessful due to enrollment not reaching target numbers (14). Although terminated early, the Thrombolysis and Counterpulsation to Improve Cardiogenic Shock Survival (TACTICS) Trial showed that 6-month mortality was lower in a subset of patients (n=31) randomized to fibrinolysis and early IABC compared with those randomized to fibrinolysis alone (39% vs. 80%, p=0.05)(14).

The independent association of CRH and ERV with survival in our analyses suggests that the lack of a rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion may be an important prognostic variable. In both treatment groups of the SHOCK Trial (emergency revascularization and initial medical stabilization), patients with CRH had a substantially lower mortality at 30-days and 1-year compared to NCRH patients. The absence of CRH 30 minutes after IABC initiation can help triage early, a group of patients who may perform poorly post revascularization for other therapies.

When systemic reperfusion is reversed in response to IABC is this simply reflecting underlying myocardial reserve, or is effective augmentation improving myocardial perfusion leading to better survival, or both? The finding of a higher LVEF and a lower burden of coronary artery disease as correlates of CRH supports the myocardial reserve hypothesis. However, the small absolute difference in LVEF, systolic blood pressure, and the coronary jeopardy score is consistent with the presence of other factors in need of further scrutiny.

Our observations support the need for continued search for newer therapies despite the recent disappointments in this field of investigation (15). In the SHOCK Trial, the 1-year survivors enjoyed a high level of quality of life and functional capacity (16). In addition to this in an analysis of the GUSTO trail amongst 30-day survivors of CS following a MI had a similar annual mortality to patients without CS when followed for 11 years (17).

The imbalance of this prognostic variable between the two treatment groups in the SHOCK Trail potentially explains why the mortality reduction at 30-days with emergent revascularization was not statistically significant. The CRH variable was unevenly distributed in the SHOCK Trial, with a higher proportion of initial medical stabilization patients having this positive response compared with emergent revascularization patients. This imbalance was random and unrelated to an interaction of emergent revascularization and CRH. When the imbalance for the CRH variable was adjusted for using only available data, emergent revascularization patients had significantly better 30-day survival (p=0.03), with an OR of 0.43 (95% CI 0.20, 0.93). However, due to missing data on tissue perfusion (n=70), this analysis cannot be extrapolated beyond hypothesis generation.

The use of IABC in CS patients is associated with a risk of severe bleeding and ischemic complications, with an incidence similar to that of acute renal failure. The absence of an association between fibrinolytic therapy and IABP on the incidence of severe bleeding is further support for initiating IABC and fibrinolysis early, not only when mechanical revascularization is unavailable, but also when it is unduly delayed. Our reported incidence of major bleeding complications with IABC is higher than that reported by Ferguson et al. (18). However, their reported incidence of <1% for both major bleeding or major limb ischemia is derived from a healthier population where the major indications for IABC were CS (18.8%), prophylactic use in high-risk patients (13.0%), support during or after cardiopulmonary bypass (36.7%), and refractory angina pectoris (12.3%). The presence of pulmonary edema on an admission chest X-ray, duration of IABC, and hospital stay were significant correlates of a complication occurring with IABC (with or without fibrinolytic therapy), supporting the notion of our patients being considerably sicker. Regardless, the risk-benefit ratio for IABC remains favorable in CS patients.

Study Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis. The primary outcome measure in our study was the subjective assessment of rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion using a binary scale. As such, variability in the assessment of tissue perfusion status is likely to have influenced the results in either direction. Given the magnitude of the effect with CRH on survival, the overall conclusion is likely to be valid and not and unlikely to be due to unmeasured residual confounders that may have occurred at the time of IABC insertion.

In combining patients from the SHOCK Trial and Registry, there is an inherent danger of selection bias in the Registry patients. In contrast to the Trial, where the recommendation for IABC resulted in its use in most patients, physician preference determined care in the Registry, resulting in lower utilization rates. Despite this, there was no significant difference in the rate of CRH between the Trial and Registry patients, nor was there a difference in the association with survival. The SHOCK Trial consisted of patients meeting strict criteria for cardiogenic shock following acute myocardial infarction without any exclusion, patients in the concurrent SHOCK Registry consisted of those with at least one exclusion criterion (58%) with the remainder not meeting all inclusion criteria. The physiological response to IABC, namely reversal of systemic hypoperfusion, was assessed at a single time point. As such, an opportunity was lost to further understand the physiological effects of IABC occurring later. A number of other unrecorded variables, such as the dose of vasopressors required initially, could have influenced subsequent outcomes. In addition, covariate-adjusted models had reduced sample size due to missing data for LVEF.

Conclusions

Rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion with IABC is an important clinical indicator that is strongly associated with a lower 30-day and 1-year mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating an acute myocardial infarction. The mortality reduction with CRH is independent of other known predictors of lower mortality, including emergency revascularization.

The relationship between CRH and survival independent of other factors suggests that CRH is a marker of viability or myocardial reserve, requiring additional prospective elucidation. Future investigation is needed to discover new therapies for the treatment of patients with persistent tissue hypoperfusion post revascularization, and whether this will further reduce mortality in CS patients.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CRH

rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion

- CS

cardiogenic shock

- IABC

intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation

- LV(EF)

left ventricular (ejection fraction)

- NCRH

non-complete rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion

- MI

myocardial infarction

- SHOCK

SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for shocK?

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 76th Annual Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association, Orlando, Florida, November 2003.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Babaev A, Every N, Frederick P, Sichrovsk T, Hochman JS. Trends in revascularization and mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Observations from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2002;106:1811. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Sanborn TA, White HD, Talley JD, Buller CE, Jacobs AK, Slater LN, Col J, McKinlay SM, LeJemtel TH for the SHOCK Investigators. N Eng J Med. 1999;341:625–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urschel CW, Eder L, Forrester J, Matloff J, Carpenter R, Sonnenblick E. Alterations of mechanical performance of the ventricle by intraaortic ballloon counterpulsation. Am J Cardiol. 1970;25:546–51. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(70)90593-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webber KT, Janicki JS. Intraarotic balloon counterpulsation: a review of physiological principles, clinical results and device safety. Ann Thorac Surg. 1974;17:602–36. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)65706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson RD, Ohman EM, Holmes DR, Col I, Stebbins AL, Bates ER, Stomel RJ, Granger CB, Topol EJ, Califf RM. Use of intraaortic balloon counterpulsation in patients presenting with cardiogenic shock: observations from the GUSTO-1 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:708–15. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanborn TA, Sleeper LA, Bates ER, Jacobs AK, Boland J, French JK, Dens J, Dzavik V, Palmeri ST, Webb JG, Goldberger M, Hochman JS. Impact of thrombolysis, intraarotic balloon pump counterpulsation, and their combination in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1123–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochman JS, Buller CE, Sleeper LA, Boland J, Dzavik V, White HD, Lim J, LeJemtel T for the SHOCK Investigators. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction-etiologies, management and outcome: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1063–70. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00879-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Godfrey E, McKinlay SM, Sanborn T, Col J, Le Jetel T for the SHOCK Trial Study Group. Should we emergently revascualrize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock: an international randomized trial of emergency PTCA/CABG – trial design. Am Heart J. 1999;137:313–21. doi: 10.1053/hj.1999.v137.95352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Califf RM, Phillips HR, III, Hindman MC, et al. Prognostic value of a coronary jeopardy score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:1055–63. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waksman, Weiss AT, Gotsman S, Hasin Y. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation improves survival in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1993;14:71–74. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moulopoulos SD, Stamateolopoulos SF, Nanas JN, Kontoyannis DA, Nanas SN. Effect of protracted dobutamine infusion on survival of patients in cardiogenic shock treated with intraaortic balloon pump. Chest. 1993;103:248–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.1.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menon V, Hochman JS, Stebbins A, Pfisterer M, Col J, Anderson RD, Hasdai D, Holmes DR, Bates ER, Topol EJ, Califf RM, Ohman EM for the GUSTO Investigators. Lack of progress in cardiogenic shock: lessons from the GUSTO trials. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1928–36. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, Gurwitz J, Bigelow C, Gore JM. Temporal trends in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. N Eng J Med. 1999;340:1162–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohman ME, Nannas J, Stomel RJ, Lesser MA, Nielson D, Hudson MP, Fraulo B, Shaw LK, et al. Thrombolysis and counterpulsation to improve cardiogenic shock survival (TACTICS): results of a prospective randomized trial. Circulation. 2000;102 #18 Supplement II-600 Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 15.TRIUMPH Investigators. Alexander JH, Reynolds HR, Stebbins AL, Dzavik V, Harrington RA, Van de Werf F, Hochman JS. Effect of tilarginine acetate in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock: the TRIUMPH randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1657–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.15.joc70035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sleeper LA, Ramanathan K, Picard MH, Lejemtel TH, White HD, Dzavik V, Tormey D, Avis NE, Hochman JS SHOCK Investigators. Functional ststus and quality of life after emergency revascularization for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:266–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh M, White J, Hasdai D, Hodgson PK, Berger PB, Topol EJ, Califf RM, Holmes DR., Jr Long-term outcome and its predictors among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction complicated by shock: insights from the GUSTO-I trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(18):1752–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson JJ, III, Cohen M, Freeman RJ, Jr, Stone GW, Miller MF, Joseph DL, Ohman EM. The current practice of Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation: results from the Benchmark Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1456–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]