Abstract

Background

Tobacco companies have come under increased criticism because of environmental and labor practices related to growing tobacco in developing countries.

Methods

Analysis of tobacco industry documents, industry web sites and interviews with tobacco farmers in Tanzania and tobacco farm workers, farm authorities, trade unionists, government officials and corporate executives from global tobacco leaf companies in Malawi.

Results

British American Tobacco and Philip Morris created supply chains in the 1990s to improve production efficiency, control, access to markets, and profits. In the 2000s, the companies used their supply chains in an attempt to legitimize their portrayals of tobacco farming as socially and environmentally friendly, rather than take meaningful steps to eliminate child labor and reduce deforestation in developing countries. The tobacco companies used nominal self-evaluation (not truly independent evaluators) and public relations to create the impression of social responsibility. The companies benefit from $1.2 billion in unpaid labor costs due to child labor and more than $64 million annually in costs that would have been made to avoid tobacco related deforestation in the top twelve tobacco growing developing countries, far exceeding the money they spend nominally working to change these practices.

Conclusions

The tobacco industry uses green supply chains to make tobacco farming in developing countries appear sustainable while continuing to purchase leaf produced with child labor and high rates of deforestation. Strategies to counter green supply chain schemes include securing implementing protocols for the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control to regulate the companies’ practices at the farm level.

World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control1 (FCTC) Articles 17 and 18 require the development of economically sustainable alternatives to tobacco growing. Policy options and recommendations to implement these articles will be presented at the fifth session of the Conference of the Parties in fall 2012.2 Articles 17 and 18 seek to address economic concerns of people and communities growing tobacco and ameliorate tobacco growing’s social and environmental costs, including deforestation, soil depletion and erosion, water table pollution,3, 4 pesticide and nicotine poisoning of workers and child labor, particularly in developing countries.5-8 Tobacco farming occupies about four million hectares9 globally and is responsible for 4% of annual global deforestation, about 200,000 hectares annually.4 In addition, tobacco companies concerned with economic performance often negotiate such low prices with leaf companies that production requires child labor and debt servitude.5, 10, 11

In response to growing public awareness of these issues, the tobacco industry integrated these issues into the “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) campaigns they use to build goodwill to protect their power to influence policymaking8, 12-20 and open and protect markets.21 In the 1990s, the companies created supply chains to procure tobacco leaf and improve production efficiency, and control access to markets and profits. (Before the 1990s, PM and BAT were not concerned with the tobacco growing practices for the leaf they procured from leaf buying companies.) In this paper we show that PM and BAT adapted and “greened” their supply chain practices by integrating environmental and labor considerations in the 2000s to serve their CSR campaigns in an effort to legitimize portrayals of tobacco farming as socially and environmentally friendly, while keeping actual practices essentially unchanged.

METHODS

We used the tobacco industry documents released as of August 2010 in the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (legacy.library.ucsf.edu), initially searched with the terms “supply chain(s),” “tobacco farming,” “environment,” and “social responsibility in tobacco production” using standard snowball approaches,22, 23 including examining adjacent documents (Bates numbers) and searching names of key individuals and organizations. We screened 3,211 documents for this analysis. We searched Lexus Nexus, World Cat, the University of California library catalog, internet search engines, and tobacco industry websites for annual reports and information on social responsibility in tobacco production schemes.

Dr. Otañez conducted semi-structured interviews with 124 tobacco farm workers, farm authorities, trade unionists, government officials and corporate executives from global tobacco leaf companies during six visits to Malawi between 1998 and 2006. Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with 36 tobacco farmers in Tanzania in 2009. Interviews were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Colorado at Denver and University of California San Francisco Committees on Human Research.

RESULTS

The Tobacco Supply Chain

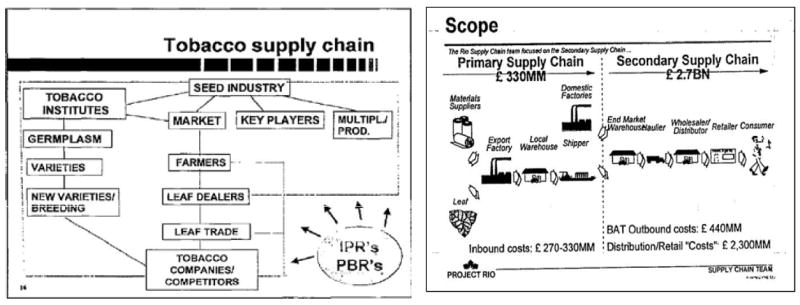

The supply chain consists of companies engaged in seed and crop science, tobacco growing, harvesting, leaf selling, transportation, storage, ingredient (additive) supply, cigarette manufacturing and retailing (Figure 124, 25). PM, BAT, Japan Tobacco International (JTI) and Imperial Tobacco represented 80% of leaf company Universal Corporation’s business in 200626 and 68% of Alliance One’s in 2008.27 In 2010, BAT purchased 400,000 tons of tobacco through contracts with 250,000 farmers in developing countries through 100 BAT leaf suppliers, making BAT the world’s third largest leaf company.28, 29

Figure 1.

Philip Morris’ tobacco supply chain in 199824 (left) and British American Tobacco’s in 199625 (right). (IPR: Intellectual Property Rights; PBR: Plant Breeder’s Rights.)

Supply Chain Initiatives

In the 1990s, both PM and BAT reorganized their supply chains to streamline production and increase profits (Figure 1). Modeled on a successful cost-cutting initiative in its Kraft Foods subsidiary, in 1991 PM created its “supply chain initiative,”30,31 which by 1996-1998 sought to “manage the complete [worldwide] leaf supply chain, focus on reasonable margins at all stages to ensure continuous leaf production, balanced market conditions and to avoid further dealer concentration [emphasis in original].”32 BAT launched supply chain activities in 1995 focused on reducing costs, increasing information access, increasing control over leaf purchases.25, 33-39 In 1996 BAT concluded that its efforts reduced the supply chain cost 7% while increasing availability of BAT cigarettes worldwide.40

In 2000, PM launched its “Tobacco Identity Preservation Program” (TIPP) to trace tobacco from farm to cigarette and ensure cigarettes were free from genetically modified tobacco and non-tobacco materials.41 In 2004, PM launched “Good Agricultural Practices” (GAPS), a program previously adopted by other industry groups,42, 43 to encourage farmers participating in the Tobacco Farmer Partnering Program to reduce tobacco-related environmental harm to water and land.44 (We were unable to determine this initiative’s effect.)

Integrating Leaf Supply Chain into CSR

In July 1998, the BAT External Affairs Manager in Group Public Affairs reported to BAT Chairman Martin Broughton that the company’s Leaf Department had successfully publicized BAT’s environmental and agricultural performance.45 At this point, BAT had not yet decided what to focus on in its CSR activities, but did want to do something different from other tobacco companies.45 She noted, “Both Rothmans and Philip Morris International focus attention on the Arts and on Motor Sports sponsorship -- thus providing BAT an incentive and opportunity to do something different” in CSR.45 In February 1999, the head of the company’s Leaf Department, in his annual “Future Business Environment” report stated, ”The whole area of “social responsibility” (Agricultural Chemicals, Genetically Modified Tobaccos, afforestation, employment practices, etc) will become Global issues with escalating Global consequences.”46 This was the first time “social responsibility” appeared in the “Future Business Environment” and contributed to the momentum for integrating tobacco production into CSR.

Similarly, in 2001 PM’s Corporate Responsibility Taskforce recommended supply chain management as a strategic priority for PM.47 PM hired Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) to study its CSR reputation from the perspective of environmental groups, among other stakeholders, and identify external partners.48 BSR’s confidential report concluded that environmental groups respect companies that put a high value on supply chain management.48 These conclusions were integrated into PM’s CSR approach. At the launch of PM’s Corporate Responsibility Taskforce in October 2000, PM’s chairman stated that PM’s “goal is to redefine the role of a corporation in American society. …To deal with our product issues and figure out how to deliver social value on a large scale.”49 The company used external social reports to disseminate information on reductions in environmental emissions and child labor and improvements in worker safety.50

BAT created the Eliminate Child Labor in Tobacco (ECLT) foundation in 2000 in response to criticism of its child labor practices in Malawi and elsewhere.51 PM joined ECLT after BAT created it. Referencing ECLT in 2002, PM’s Vice President of Corporate Affairs, Strategy and Social Responsibility, stated that PM’s “New Corporate Issue Management Process: came up with a new global policy [on] child labor, particularly in the supply chain[.] New understanding [in PM] that it is not just about products and the marketing- about corporate citizenship and about the whole value chain.”52

Self-Reporting through Leaf Companies

In addition to internal changes, the companies also presented themselves as socially and environmentally responsible by developing self-reporting mechanisms for their leaf suppliers. Starting in 2002, and continuing through at least 2010,53 PM launched the “Good Agricultural Program: Guidelines and Assessment” that presented expectations of its leaf suppliers and a method for measuring, through self-report, suppliers’ performance in six areas: mission and values (including addressing child labor), variety management and integrity, crop management, integrated pest management, sustainability (including participation in reforestation projects), and product integrity.54

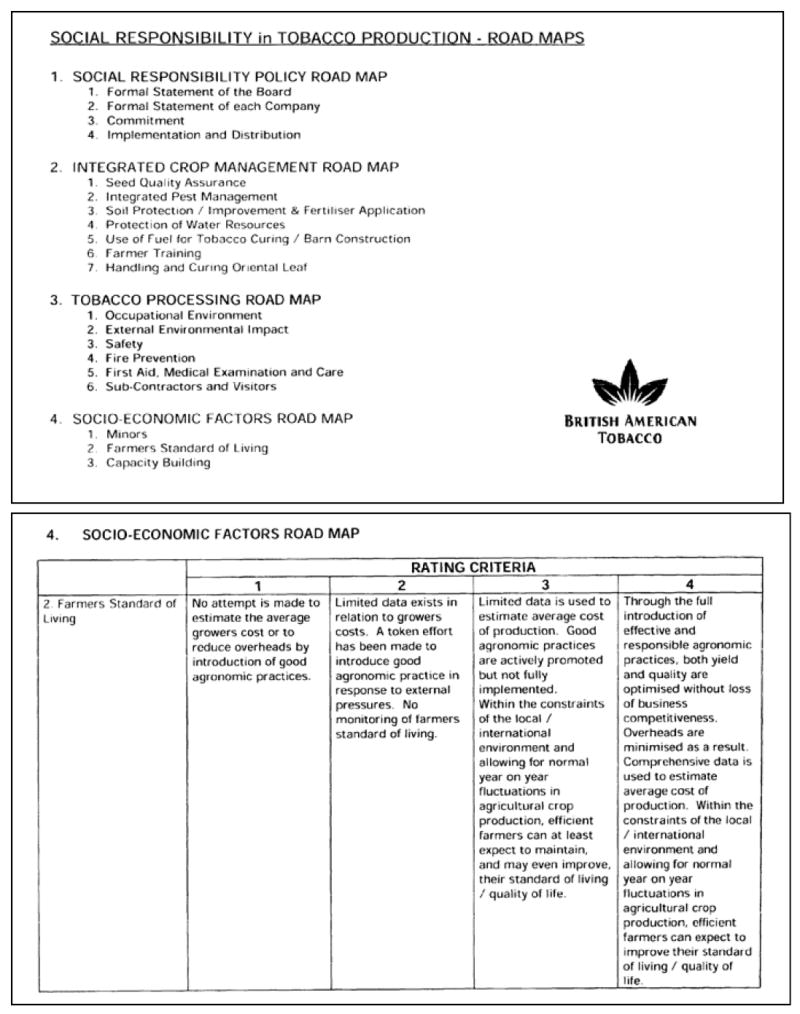

BAT’s “roadmap” for supplier self-reporting on social and environmental responsibility started in the Leaf Department. The initiative, titled “Leaf Social Responsibility Program” (Leaf SRP), was based on a similar approach BAT used beginning in Germany55 in 1996 to maintain cigarette blend integrity and supply security.55 In 2000, BAT expanded Leaf SRP into a company-wide CSR program, “Social Responsibility in Tobacco Production” (SRTP), nominally to ensure that the global suppliers who provided BAT with 40% of its leaf56, 57 to “score the social responsibility aspects of tobacco production through a road mapping approach.”58 The roadmap, consisted of guidelines, rating criteria, and an action plan for BAT leaf suppliers, including addressing child labor, rural development and deforestation59 (Figure 260). On December 8, 2000, Robin Crellin, head of BAT’s Leaf Department, emailed BAT’s Corporate Communication Manager, reporting that “all 120 or so external Leaf Merchant Companies that BAT use or may in future choose to use for Leaf Supply have been personally briefed by members of Leaf Technology in the self-assessment Map and Action Plan, and 110 or so responses have been received so far.”61

Figure 2.

(Top) British American Tobacco’s “Social Responsibility in Tobacco Production: Road Maps” and (bottom) “Socio-Economic Factors Road Map” outline the company’s efforts to integrate supply chain activities and corporate social responsibility schemes to make tobacco farming appear socially and environmentally sustainable.60

The rating criteria fail to address issues of living wages or freedom of association to form trade unions. Rather than using truly independent assessors, BAT has the leaf suppliers rate themselves as through a voluntarily self-assessment. Self-assessment may produce data that are unreliable, subjective and superficial.8

Use of “Independent” Partners

BAT, PM and other tobacco companies also promoted their image of social responsibility by partnering with nominally independent, but affiliated, organizations for green supply chain initiatives and evaluations.

BAT: LeafTc (Leaf Technology Consultancy)

BAT’s webpage “Our SRTP Reviews” where BAT listed leaf suppliers’ scores as of May 15, 2010, stated that “the reviews are carried out for us by an independent consultancy, LeafTc” (Leaf Technology Consultancy) and provides a link to LeafTc’s website.62 Established in April 2002, LeafTc manages CSR for several clients with a “mission to improve standards in the agribusiness supply chain as they relate to crop production and processing.”63

LeafTc’s co-founders and co-directors, Robin Crellin and Adrian Barnes, worked for BAT from 1972 to 2002 and 1976 to 2001, respectively, where they developed BAT’s SRTP roadmap.64 LeafTc’s website did not mention their work history with BAT as of May 15, 2010, but did state that “The SRTP Programme was designed to complement and further enhance the ‘SRTP Roadmaps’ as developed by British American Tobacco”65 In 2005, BAT in “Roadmaps and our SRTP reviews” in its Social Report 2004/5 stated that, “roadmaps stimulate self-driven continuous improvement. They help suppliers to progress at rates suited to particular development, financial and technical circumstances.”66 (While BAT was LeafTc’s first tobacco client, other companies followed.67, 68)

Public relations statements about SRTP success did not mean behavior change by leaf suppliers. Ethnographic data obtained by Otañez from tobacco farmers in Malawi and Tanzania and literature on the socio-ecological costs of tobacco3, 69, 70 show US-based Universal Corporation and Alliance One International continuing to purchase leaf produced by child labor, perpetuate debt servitude schemes for tobacco farmers, and contributing to deforestation through tobacco growing.

In 2005, BAT revised its SRTP roadmaps to include use of wood for tobacco barn construction and other biodiversity issues (these issues are unstated but may refer to use of agrochemicals and impact on water tables and soil nutrients).71 In 2005, Crellin stated in a presentation at the Business and Biodiversity Resource Center, a corporate greenwashing group based in Oxford, UK, that SRTP biodiversity had impacted 150 tobacco suppliers in 50 countries and 1,000,000 growers.71 (Corporate greenwashing describes practices of corporations to present themselves as promoting environmentally sustainable activities such as reforestation projects in their public relations activities to improve corporate images without fundamentally changing core business practices.72) The results discussed by Crellin refer only to suppliers and growers who agreed to use a LeafTc form to conduct annual self-assessments and report the results to LeafTC.

PM: Total LandCare

One of PM’s first public relations supply chain projects was with the International Research and Development Department at Washington State University (WSU) in the United States. In 1999, WSU professors Trent Bunderson and Ian Hayes, and Zwide Jere, an agricultural scientist and former land husbandry officer with Malawi’s Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, created Total LandCare, a nongovernmental organization operating in Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, Tanzania, the Philippines and Argentina.73-75 (We could not determine PM’s role, if any, in creating Total LandCare.) According to Philip Morris International’s “Grower community program plan year 2000,”76 PMI’s senior management in Europe approved Total LandCare’s agriculture program, which was to “be overseen by the Leaf/Operations department in CEMA [PMI’s Central Europe, Middle East and Africa region].”76 In June 2001, Total LandCare and PM, launched the Agroforestry Partnership Program, a five-year project to reduce deforestation and soil degradation in Malawi,77 with PM providing $605,000 in 2001-2006.78 PM is Total LandCare’s largest contributor, providing more than $14 million since 2001.79 Total LandCare is a partner in a forestation project in Malawi funded by the tobacco industry’s ECLT,51 which provided $900,000 to Total LandCare in 2002-2010.80

PM executive Theodor Baseler,81 because he was a member of WSU Foundation board,82 may have played a role in arranging PM funding of Total LandCare. From 2001-2010, PM provided grants to WSU and WSU Foundation for tobacco-related reforestation projects, water and soil conservation, and farm productivity, totaling $20.9 million for 2006-2013.74, 83 In 2006, WSU Foundation honored PM for its commitment to WSU in working to promote sustainable development in Malawi and southern Africa.77

Total LandCare also received money from the US Agency for International Development ($9 million), the Community League of the USA ($234,000) in 2000-200674 and the government of Norway ($5.5 million) in 2008-2010.84

Between 2005 and 2010 Total LandCare also received money for supply chain social responsibility schemes from Imperial Tobacco,85 Alliance One International, Universal, and JTI, including loaning money to Tanzanian farmers to purchase oxen and equipment necessary to grow tobacco86, 87 and developing reforestation projects88 in Malawi and Tanzania.89 90 These projects had little effect on farmers. Weaknesses of the oxen initiative include the high cost of oxen and the short period to repay loans to buy them.91 (We have been unable to determine the interest rates for these loans.) A pair of oxen and associated training costs $320,86 which is beyond the reach of most of the 80,000 tobacco farmers in Tanzania who earn $200 a year.92

In 2005, Universal Corporation’s Malawi subsidiary Limbe Leaf and German Technical Cooperation, a private global group promoting legitimate sustainable development, collaborated to promote rocketbarns that reduce wood use by 50% for curing.93 After 2005, Imperial Tobacco, Alliance One, Japan Tobacco International (JTI), and PM also funded rocketbarns.93 Initial seed funds and some subsequent funding include $5,000 from Alliance One, $60,000 from PM, and $16,000 from JTI.94 (Imperial Tobacco does not report funds for the rocket barn project.95) The project has had little impact on wood use because each rocketbarn costs $700,93 too expensive for Malawians, 65% of whom survive on $2 a day or less.96 As of September 2010 about 1,000 barns on approximately 1,000 tobacco farms out of a total of 400,000 tobacco farms in Malawi had been installed.97

Participation in Global CSR Business Groups

Tobacco companies participate in truly independent reviews of their supply chain environmental responsibility efforts. UK-based Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) is an independent not-for-profit organization that helps corporations greenwash their environmental records98, 99 founded in 2000, which developed a method100 to report companies’ carbon footprint throughout their supply chains;101 100 JTI submitted CDP questionnaires in 2003-2007, Imperial in 2004-2007, and Altria (PM) and BAT’s Reynolds American starting in 2007.100

UK-based Imperial Tobacco, the fourth largest cigarette manufacturer, is a pilot member in CDP’s “Supply Chain Leadership Collaboration.” In 2008, Imperial’s manager of social responsibility and occupational health and safety said Imperial collaborates “with the CDP on the development of a simple and effective cross-industry framework to assess climate change risks and opportunities across supply chains, as well as to account for their greenhouse gas emissions. Our aim is to prepare ourselves and our suppliers step by step for a marketplace where measuring and managing carbon is no longer optional, while keeping the administrative burden to a minimum.”101 Tobacco industry participation in CDP allowed companies to be listed on CDP website as corporate participants, contributing to the companies’ efforts to obtain legitimacy for their environmental responsibility activities, and enabling companies to promote their participation in CDP in their own corporate social and annual reports.

Environmental and Social Costs of Tobacco Production Remain Essentially Unchanged

BAT’s SRTP project was flawed from the outset. BAT international development affairs manager Opukah, told delegates at a BAT-organized 2000 child labor conference in Kenya that SRTP “covers all the major areas of tobacco production in the supply chain such as integrated crop management, tobacco processing, workplace environment health and safety, and socioeconomic factors like child labour, farmers’ living standards and capacity building.”59 In contrast, on September 26, 2000, two weeks before the Kenya conference, an official with Malawi Africa Leaf, a subsidiary of Tribac Leaf tobacco supply company in Zimbabwe, responded to BAT’s road map questionnaire, reporting that “in a peasant producing environment it often impossible to enforce these [SRTP] commitments on family run units.”60 Between 2001-2009, BAT conducted 212 SRTP reviews in over 15 countries, reviewing 96% of the 100 operations of BAT’s leaf suppliers.62 BAT found that leaf suppliers’ scores out of a maximum of four points each for “social responsibility policy,” “tobacco processing,” “agronomy,” and “socio-economic factors” increased from an average of 3.04 (out of 4.00) to just 3.14 from 2005 to 2009.62 (A score of 3 is “Adequate and proactive risk management but does not manage all risks systematically” and 4 is “Management to best international practice standards” (score 4).71) In the 2000s BAT emphasized responsibility in tobacco production and performance reviews of leaf suppliers to make the company and tobacco farming appear socially and environmentally friendly.

In 2009 during discussions between one of the authors (Otañez) and tobacco farm workers in Tabora, Tanzania, Africa’s third largest tobacco growing country, farm workers revealed that tobacco growing in Tanzania is characterized by child labor, debt servitude of tobacco farmers due to high debts to tobacco companies, and downgrading of (assigning a lower quality to) leaf by tobacco companies. Tabora produces 60% of tobacco grown in Tanzania,102 and is the site of child labor and reforestation projects funded by through the industry’s ECLT Foundation and administered through Total LandCare. However, farm workers indicated that representatives from Alliance One International, a US-based leaf company with subsidiary operations in Tanzania and that sells through pre-arranged contracts with PM, BAT, JTI and Imperial Tobacco, knowingly buy tobacco from farms where child labor persists in Tanzania and other developing countries.

Tobacco industry reforestation schemes have little or no positive impact because the trees planted are non-native and used for tobacco production. Planting eucalyptus, cypresses and other non-native plants is problematic because the trees absorb excessive amounts of water that harm food crops and reduce drinking water tables. Moreover, the fast-growing trees are used for tobacco curing not replenishing forests destroyed by tobacco growing.103 Support from BAT to farmers of tree seedlings for reforestation is limited and inconsistent.104 In 2010, after three decades of tobacco industry tree-planting initiatives in Kenya, massive deforestation persists in the country’s key tobacco growing areas.105

Cost Effectiveness of CSR

Through Total LandCare and ECLT, BAT, Philip Morris, Japan Tobacco, and Imperial Tobacco budgeted $22.2 million over the 13 years from 2001 to 2014 for social responsibility projects aimed at reducing tobacco-related child labor and deforestation in Malawi, Tanzania, Mozambique and Zambia. Total LandCare reported that in 2007-2008, it planted 1.7 million trees in Malawi and 2 million in Tanzania.89 JTI’s tree planting project amounts to about 6% of the annual costs of tobacco-related deforestation in Malawi ($6.4 million) and Tanzania ($1.4 million) (Table 1). In comparison, tobacco companies benefit from cost savings due to child labor (Table 2) and deforestation (Table 1). (These estimates do not include the benefits to the companies of many other social and environmental costs that they avoid.) These two benefits alone come to $97.1 million/year for the tobacco companies, about $1.2 billion over 13 years, over 50 times the $22.2 million they spent on their CSR supply chain activities in these countries through ECLT and Total LandCare.

Table 1.

Costs of Deforestation in Selected Tobacco-Growing Developing Countries106

| Production Metric Tonnes 2008 | Global Tobacco Leaf Production % 2008 | Land Devoted to Tobacco Production (hectares) 2008 | Annual Costs of Tobacco-Related Deforestation* (US$ millions) | Tobacco-related deforestation rates107 (per year) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 850,000 | 12 | 431,000 | 17.2 | NA |

| India | 520,000 | 8 | 370,000 | 14.8 | NA |

| Argentina | 170,000 | 2 | 92,000 | 3.6 | 4 |

| Indonesia | 170,000 | 2 | 199,000 | 7.9 | NA |

| Malawi | 160,000 | 2 | 162,000 | 6.4 | 27 |

| Pakistan | 108,000 | 2 | 51,000 | 2.0 | 27 |

| Turkey | 100,000 | 1 | 121,000 | 4.8 | NA |

| Zimbabwe | 79,000 | 1 | 52,000 | 2.0 | 27 |

| Thailand | 70,000 | 1 | 40,000 | 1.6 | 1 |

| Mozambique | 64,000 | 1 | 33,000 | 1.3 | NA |

| Tanzania | 51,000 | 1 | 37,000 | 1.4 | 4 |

| Zambia | 48,000 | 1 | 45,000 | 1.8 | 1 |

| Total Selected | 2,390,000 | 34 | 1,632,000 | 64.8 | NA |

| Total World | 6,881,000 | 100 | 4,000,0009 | 160.0 | NA |

Based on an estimated $40/hectare in non-timber value per hectare.108 The figure of $40 of land depleted of trees “comes from adding the value of various services that forests perform, such as providing clean water and absorbing carbon dioxide.”109 The figure does not specifically refer to the economic value of the trees themselves. This cost estimate does not include the value of lost recreation, bioprospecting, watershed protection, or carbon sequestration.108

NA, Not available.

Table 2.

Costs of Child Labor in Selected Tobacco Growing Developing Countries

| Total Employment in Tobacco Growing | Child Laborers in tobacco farming (14 years and younger) | Minimum daily wage, US$ | Unpaid Costs of Child Labor (child laborers X daily wage X 198 days), US$ (million) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 910,000110 | 166,400111 | 8.40 | 276.8 |

| India | 850,000112 | 500,000* | 3.00 | 297.0 |

| Argentina | 156,000* | 34,000* | 15.00 | 100.0 |

| Indonesia | 683,603113 | 170,900114 | 0.40113 | 13.5 |

| Malawi | 586,000112 | 72,00051 | 0.75 | 10.7 |

| Pakistan | 80,000115 | 20,000* | 2.00 | 7.9 |

| Turkey | 586,616* | 117,323* | 18.00 | 418.1 |

| Zimbabwe | 100,000112 | 6,400* | 1.00 | 1.3 |

| Thailand | 31,708 112 | 6,341* | 4.50 | 5.6 |

| Mozambique | 124,000116 | 96,000117 | 2.00118 | 38.0 |

| Tanzania | 200,000119 | 80,000* | 1.25 | 19.8 |

| Zambia | 60,000120 | 30,000121 | 3.00122 | 17.8 |

| Total Selected | 4,367,927 | 1,299,364 | 1,206.6 | |

| World Total | 40,000,000112 | NA |

Estimate;

NA Not available.

DISCUSSION

PM, BAT and other cigarette companies developed supply chain projects in the 1990s to increase control over the production process, which were used to foster images of corporate responsibility in tobacco farming in the 2000s. At the same time, the companies saved and estimated $1.2 billion/year (Table 2) that could have been used to pay for children’s labor and reforestation in tobacco growing developing countries, far exceeding their expenditures directed at nominally addressing these problems. Tobacco industry programs failed because problems of child labor and deforestation are too intractable for easy solution, and industry programs are inherently flawed.

Critics have attacked such self-proclaimed “ethical and green business” practices as public relations schemes to improve corporate images and expand market shares without fundamental changes in core business practices.123-125 Through reforestation, soil protection, and child labor prevention projects in tobacco growing countries, tobacco manufacturers make it more difficult for officials and policymakers in health ministries to argue for crop diversification and alternative livelihoods for tobacco farmers as required by FCTC Articles 17 and 18. Tobacco industry reforestation schemes contribute to a situation where government officials and health policymakers in developing countries without revenues to operate their own reforestation scheme are reluctant to criticize tobacco companies or jeopardize tobacco company money available for reforestation.6, 126 Association with social and environmental responsibility may weaken opposition from public health and civil society groups to industry interference in tobacco control policy by making it politically more difficult to criticize tobacco companies.

Tobacco company partnerships with development organizations such as Total LandCare, “independent” consultants such as LeafTC, and corporate ethical groups such as the Carbon Disclosure Project are key elements in CSR in tobacco production schemes. These entities congratulate companies for their environmental improvements and produce positive news stories tobacco companies circulate to legitimize their claims of green supply chains and environmentalism.127-130

Imperial Tobacco and JTI joined CDP to demonstrate the company’s commitment to publicly report greenhouse gas emissions and portray themselves as corporate pioneers in creating green tobacco supply chains. However, disclosure and voluntary partnership with CDP does not mean superior performance131 because CDP is a commercial organization with no enforcement mechanisms.132 Tobacco companies that report their greenhouse gas emissions through CDP may experience a competitive advantage133 and increased shareholder value and better treatment by investors with growing public consciousness of climate change.134

In August 2010, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission alleged that Universal Corporation and Alliance One International, companies that purchase leaf from developing countries for Philip Morris and BAT, paid more than $5 million in bribes to government authorities in Malawi, Mozambique, China, Greece, Indonesia, and Kyrgyzstan, practices inconsistent with CSR claims.135

In 2010, the US Department of Labor formally listed tobacco from Malawi as being produced using forced child labor in violation of international standards136 over the Malawi government’s 2009 objection that “the damage to Malawi’s image would be enormous.”

Findings from interviews and field research show that future research and policy interventions to prevent the tobacco industry from using CSR in tobacco production supply chains to enhance corporate reputations without making meaningful change require a focus on the farm-level activities of tobacco companies that contradict genuine sustainability as well as transparency and human rights. More research is needed on the experiences of tobacco farmers and farm workers involved in industry-funded social responsibility in tobacco production schemes.

At the fifth session of the Conference of the Parties in South Korea in fall 2012, the WHO Working Group on Economically Sustainable Alternatives to Tobacco Growing plans to submit a working report that may include policy options and recommendations.2 Articles 17 and 18 on economically sustainable alternatives to tobacco represent a potential vehicle to systematically document child and bonded labor and deforestation along the tobacco supply chain and reduce economic dependence on tobacco farming over a generation or more in developing countries. Moreover, it is an opportunity to secure implementing protocols for the FCTC that will impose legal restrictions on the tobacco companies’ practices at the farm level. In particular, it is important to put any CSR projects and claims of progress in the context of the total social and environmental costs of tobacco production rather than accepting industry claims at face value.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Sullivan and Mariaelena Gonzalez for editorial suggestions.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant CA-87472, a postdoctoral fellowship to Dr. Otañez from the American Cancer Society, and a grant to Dr. Otañez from the Council of Ethics for the Norwegian Government Pension Fund-Global. Dr. Glantz is American Legacy Foundation Distinguished Professor in Tobacco Control. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTOR STATEMENT Otanez did the data collection; both authors collaborated in preparing the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS No competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Group and co-owners or contracting owning societies (where published by the BMJ Group on their behalf), and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Tobacco Control and any other BMJ Group products and to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license.

Contributor Information

Marty Otañez, Department of Anthropology, Campus Box 103, P.O. Box 173364, University of Colorado at Denver, Denver, Colorado 80217-3364, tel: 303 556 6606, fax: 303 556 8501, marty.otanez@ucdenver.edu.

Stanton A Glantz, Department of Medicine, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143-1390, tel. 415 476 3893, fax 415 514 9345, glantz@medicine.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. [10 July 2008];2005 www.fctc.org/index.php?item=fctc-toc.

- 2.World Health Organization. Decisions: Fourth Session; Punta Del Este, Uruguay. 15-20 November 2010; 2010. [January 4, 2011]. http://apps.who.int/gb/fctc/E/E_cop4.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geist H, Chang K-t, Etges V, Abdallah J. Tobacco Growers at the Crossroads: Towards a Comparison of Diversification and Ecosystem Impacts. Land Use Policy. 2009;26:1066–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geist H, Kapito J, Otañez M. The Tobacco Industry in Malawi: A Globalized Driver of Local Land Change. In: Jepson W, Millington A, editors. Land Change Modifications in the Developing World. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2008. pp. 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otañez MG, Muggli ME, Hurt RD, Glantz SA. Eliminating Child Labour in Malawi: A British American Tobacco Corporate Responsibility Project to Sidestep Tobacco Labour Exploitation. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:224–30. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel P, Collin J, Gilmore AB. “The Law Was Actually Drafted by Us but the Government Is to Be Congratulated on Its Wise Actions”: British American Tobacco and Public Policy in Kenya. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:e1. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.016071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plan International. Plan International; 2009. [February 20, 2010]. London, UK Hard Work, Long Hours and Little Pay: Research with Children Working on Tobacco Farms in Malawi. http://plan-international.org/about-plan/resources/publications/protection/hard-work-long-hours-and-little-pay. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barraclough S, Morrow M. A Grim Contradiction: The Practice and Consequences of Corporate Social Responsibility by British American Tobacco in Malaysia. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1784–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society; 2009. [May 20, 2010]. Atlanta Tobacco Atlas. www.cancer.org/docroot/AA/content/AA_2_5_9x_Tobacco_Atlas_3rd_Ed.asp?sitearea=&level= [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchanan J. Human Rights Watch; 2010. [December 22, 2010]. New York ‘Hellish Work’: Exploitation of Migrant Tobacco Workers in Kazakhstan. www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/07/14/hellish-work-0. [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacKerron C. The Human Cost of Greening the Supply Chain. [July 1, 2009];2009 www.csrwire.com/csrlive/commentary_detail/101-The-Human-Cost-of-Greening-the-Supply-Chain-

- 12.World Health Organization. Tobacco Industry Strategies to Undermine Tobacco Control Activities at the World Health Organization. [11 July 2008];2000 www.who.int/entity/tobacco/resources/publications/general/who_inquiry/en/index.html.

- 13.Hirschhorn N. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Tobacco Industry: Hope or Hype. Tobacco Control. 2004;13:447–453. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2004. [10 Jan 2006]. Geneva, Switzerland Tobacco Industry and Corporate Responsibility…An Inherent Contradiction. www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/A95409F2-1AA9-4EC0-BEC5-FF7C336B9A6C/0/CSR_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2004. [24 Feb 2008]. Geneva, Switzerland Tobacco and Poverty: A Vicious Circle. www.who.int/tobacco/communications/events/wntd/2004/en/wntd2004_brochure_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaiton M, Ferrence R, LeGresley E. Perceptions of Industry Responsibility and Tobacco Control Policy by US Tobacco Company Executives in Trial Testimony. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Suppl 4):iv98–106. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman LC. Tobacco Industry Use of Corporate Social Responsibility Tactics as a Sword and a Shield on Secondhand Smoke Issues. J Law Med Ethics. 2009;37:819–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2009.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDaniel PA, Malone RE. The Role of Corporate Credibility in Legitimizing Disease Promotion. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:452–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tesler L, Malone R. Corporate Philanthropy, Lobbying, and Public Health Policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:2123–2133. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J, Malone R. “Working to Shape What Society’s Expectations of Us Should Be”: Philip Morris’ Societal Alignment Strategy. Tobacco Control. 2008;17:391–398. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.026476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilmore AB, McKee M. Moving East: How the Transnational Tobacco Industry Gained Entry to the Emerging Markets of the Former Soviet Union-Part Ii: An Overview of Priorities and Tactics Used to Establish a Manufacturing Presence. Tob Control. 2004;13:151–60. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco Industry Documents: Treasure Trove or Quagmire? Tobacco Control. 2000;9:334–338. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balbach ED. Tobacco Industry Documents: Comparing the Minnesota Depository and Internet Access. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:68–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philip Morris. Philip Morris Tobacco Biotechnology Working Group: Update on Progress of Worldwide Technology Assessment. [4 Jun 2008];1998 Oct 8; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jwu28d00.

- 25.Hans N. Presentation to the Tmb (Memo from Nierderman to All Members of the Project Rio Team) [9 June 2008];1996 Feb 2; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bwx03f00.

- 26.Freeman G. Remarks at the 2007 New York Investors Show (Universal Corporation) [2 May 2008];2007 http://library.corporate-ir.net/library/89/890/89047/items/270249/2007NewYorkInvestorsShow.pdf.

- 27.Finora J. Alliance One International: Making the Right Moves. Tobacco International. 2008 June [Google Scholar]

- 28.British American Tobacco. London Sustainability Report 2009. [May 11, 2010];2010 www.bat.com/group/sites/uk__3mnfen.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO7FAK65?opendocument&SKN=1.

- 29.British American Tobacco. Responsible Leaf Production. [January 5, 2011];2010 www.bat.com/group/sites/uk__3mnfen.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO52APTT?opendocument&SKN=1.

- 30.Philip Morris. Annual Report. [10 Jun 2008];1992 Dec 31; http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/qgz21a99.

- 31.Philip Morris. Business Plan 1991-1995. [4 Jun 2008];1991 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mam42e00.

- 32.Philip Morris. Operations Three Year Plan 1996-1998. [4 Jun 2008];1996 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iwg96c00.

- 33.Baxter P. Memo from Paul Baxter Regarding Capacity Requirements Used for Units 182 and 186/7. [10 Jun 2008];1992 Dec 21; http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/sbz90a99.

- 34.British American Tobacco. Bmb Minutes Index: Bbj Series 1994. [16 Jul 2008];1994 http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/fhh45a99.

- 35.British American Tobacco. Update: Winning as One. [6 June 2008];1996 June; www2.tobaccodocuments.org/batco/700561348-1355.pdf.

- 36.British American Tobacco. British American Tobacco (Holdings) Limited: Management Board Meeting - 30th January 1996; 30 Jan. 1996; [16 Jul 2008]. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/jyf60a99. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunt K. Slides from Battalion Process Speech. [30 Jun 2008];1995 Nov 29; http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/kel04a99.

- 38.Philip Morris. Competitor Review. [17 Jul 2008];1996 Apr 25; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nmb00b00.

- 39.Philip Morris. Competitor Review. [17 Jul 2008];1995 Oct 14; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ydw09e00.

- 40.British American Tobacco. Trade Marketing and Distribution Report 1995. [9 June 2008];1996 Feb 20; http://bat.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gnh81a99.

- 41.Ryan L, Gadani F, Zuber J, et al. A Global Tobacco Identity Preservation Program. [11 June 2008];2001 www.altadis-bergerac.com/pdf/4_JS_Bergerac.pdf.

- 42.Cooperation Center for Scientific Research Relative to Tobacco. A Presentation of Coresta. [9 June 2008];2008 www.coresta.org/Home_Page/PresentationCORESTA%20(May08).pdf.

- 43.Bialous SA, Yach D. Whose Standard Is It, Anyway? How the Tobacco Industry Determines the International Organization for Standardization (Iso) Standards for Tobacco and Tobacco Products. Tob Control. 2001;10:96–104. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Philip Morris. Our Initiatives and Programs: Good Agricultural Practices. [15 July 2008];2008 www.philipmorrisusa.com/en/cms/Responsibility/Reducing_Our_Environmental_Impact/Agricultural_Practices/default.aspx?src=top_nav.

- 45.Honour H. Corporate Social Responsibility. [28 May 2008];1998 Jul 27; http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/det14a99.

- 46.Snowden I Limited B-ATC. British American Tobacco; Feb 04, 1999. [30 Jun 2008]. Future Business Environment - Leaf. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/uba14a99. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Philip Morris. Corporate Responsibility Taskforce Input Ellen Merlo for Mp USA Senior Team Consideration. [November 17, 2009];2001 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/say00c00.

- 48.Business for Social Responsibility. Final Report: PM USA External Assessment for Game Plan. [17 Jul 2008];2002 Jul 2; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cmb17a00.

- 49.PMUSA Corporate Responsibility Taskforce. A Conversation About Corporate Responsibility. [August 24];2001 Mar 5; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ulw14c00.

- 50.Culley L. Script ‘Conversation on Corporate Responsibility’. [May 20, 2010];2001 May 15; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/euo10c00.

- 51.Otañez M, Muggli M, Hurt R, Glantz S. Eliminating Child Labour in Malawi: A British American Tobacco Corporate Responsibility Project to Sidestep Tobacco Labor Exploitation. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:224–230. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Philip Morris. Nicoli Smu Speech. [May 20, 2010];2002 April 7; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rdx07a00.

- 53.Philip Morris. Good Agricultural Practices. [May 10, 2010];2010 www.pmi.com/eng/about_us/how_we_operate/pages/good_agricultural_practices.aspx.

- 54.Philip Morris International. Good Agricultural Practices: Guidelines and Assessment. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unwin M. British American Tobacco; Dec 23, 1996. [16 Jul 2008]. Eppe Minutes. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/cyx34a99. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crellin R. Leaf Technology: 2000. [5 Jul 2008];2001 Sep 21; http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/scm61a99.

- 57.British American Tobacco. Social Responsibility in the Production of Tobacco (estimated) [3 Jul 2008];2000 http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/rda34a99.

- 58.British American Tobacco. 2001 Work Programme. [5 Jun 2008];2001 http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/oyk55a99.

- 59.Crellin R. British American Tobacco; Oct 12, 2000. [5 Jun 2008]. Social Responsibility in Tobacco Production. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/bom61a99. [Google Scholar]

- 60.British American Tobacco. Social Responsibility in the Production of Tobacco. [3 Jul 2008];2001 Jul 23; http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/yeu72a99.

- 61.Crellin R. British American Tobacco; Dec 8, 2000. [3 Jul 2008]. Leaf Social Responsibility Programme (Leaf Srp) http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ekm61a99. [Google Scholar]

- 62.British American Tobacco. Our Srtp Reviews. [May 10, 2010];2010 www.bat.com/group/sites/uk__3mnfen.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO6ZXKF6?opendocument&SKN=1&TMP=1.

- 63.Leaf Technology Consultants. CSR Management Services. [May 20, 2010];2009 www.leaftc.com.

- 64.Indian Tobacco Company. Itc Limited Iltd Divsion Chirala. [July 13, 2009];2004 www.greenbusinesscentre.com/images/Photos/SA-12.pdf.

- 65.Leaf Technology Consultants. The Srtp Program. [May 10, 2010];2009 www.leaftc.com/srtp.htm.

- 66.British American Tobacco. Social Report 2004/5. [May 20, 2010];2005 www.bat.com/group/sites/uk__3mnfen.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO6RZGHL?opendocument&SKN=1.

- 67.Imperial Tobacco Group. Corporate Responsibility Review 2007. [23 May 2008];2007 www.imperial-tobacco.com/files/environment/cr2007/files/PDFS/itgcr07_fullreview_highres.pdf.

- 68.Reynolds American. Definitive Proxy Solicitation Material. [December 12, 2009];2009 www.secinfo.com/dsVsf.s2De.htm.

- 69.Otañez M. Social Disruption Caused by Tobacco Growing. Study conducted for the Second meeting of the Study Group on Economically Sustainable Alternatives to Tobacco Growing WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; Mexico City. June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abdallah H. Uganda’s Forest Cover Fast Dying out as Tobacco Industry Booms. The East African (Kenya) [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leaf Technology Consultants. Independent Srtp Consultants. [4 July 2008];2005 www.businessandbiodiversity.org/ppt/Presentation%205%20-%20Robin%20Crellin.ppt.

- 72.Haskall V. The Greening of Corporate Social Responsibility: Measuring ‘Green’ and Corporate Social Responsibility. [5 June 2008];2008 www.b-eye-network.com/view/7332.

- 73.Total LandCare. Total Landcare Update. The Nation (Lilongwe, Malawi) Aug 6; [Google Scholar]

- 74.Washington State University International Programs. International Programs Development Cooperation Summary Profile of Contract/Grants/Donations 2000-2006. [11 June 2008];2007 www.ip.wsu.edu/faculty-and-scholars/assets/Contracts-Grants-Donations.pdf.

- 75.Philip Morris. Production Principles: Our Commitment to Responsible Manufacturing. [11 June 2008];2008 www.philipmorrisinternational.com/PMINTL/pages/eng/community/Principles.asp.

- 76.Philip Morris. PMI Grower Community Program Plan Year 2000. [May 20, 2010];2001 February 26; http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xtg31c00.

- 77.Philip Morris. Malawi Case Study: Reducing Environmental Impact in Malawi. [May 2, 2009];2009 www.philipmorrisusa.com/en/cms/Responsibility/Reducing/Reducing_Our_Environmental_Impact/case_studies/Malawi_Case_Study/default.aspx.

- 78.Total LandCare. Total Landcare; 2008. [Mar 20, 2010]. Lilongwe, Malawi Agroforestry Partnership Project. www.totallandcare.org/Projects/APP/tabid/80/Default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Philip Morris International. Malawian Ngo Total Landcare Receives $2.5 Million Grant from Philip Morris International. [December 22, 2010];2010 www.pmi.com/eng/media_center/press_releases/Pages/malawian_ngo_total_landcare_receives_25_million_grant_from_philip_morris_international.aspx.

- 80.Total LandCare. Integrated Child Labor Elimination Project. [May 1, 2010];2010 www.totallandcare.org/Projects/ICLEP/tabid/79/Default.aspx.

- 81.Philip Morris. Our Management Team. [May 20, 2010];2010 www.altria.com/en/cms/About_Altria/Our_Management_Team/Ted_Baseler/default.aspx.

- 82.Washington State University Foundation. Wsu Foundation Board of Trustees. [November 17, 2009];2009 http://foundation.wsu.edu/about/board-of-trustees.html.

- 83.Total LandCare. Origin and Background. [May 10, 2010];2010 www.totallandcare.org.

- 84.Government of Norway. Cooperation Norway-Malawi: Agreements and Contracts. [July 3, 2009];2009 www.norway.mw/Development/Agreement/agreements.htm.

- 85.Total LandCare. Promotion of Rural Investment in Smallholder Enterprise. [May 20, 2010];2010 www.totallandcare.org/Projects/PRISE/tabid/94/Default.aspx.

- 86.Bunderson T, Jere Z, Chisui J, et al. Enhancing Rural Livelihoods in Malawi, Tanzania and Mozambique: Annual Report July 2006-June 2007: Total LandCare. 2007 July [Google Scholar]

- 87.Semberya D. Tanzania: Oxen Project Proving a Boon in Tobacco Farming. Business Times (Tanzania) 2010 August 13; [Google Scholar]

- 88.Imperial Tobacco Group. Corporate Responsiblity Review 2009. [May 20, 2010];2010 www.imperial-tobacco.com/index.asp?page=150.

- 89.Bunderson T, Zwide J. Total Landcare; 2008. [May 2, 2010]. Lilongwe, Malawi Jt Group Community Reforestation and Support Program: Malawi and Tanzania. www.totallandcare.org/Projects/RCSP/tabid/76/Default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Japan Tobacco International. Climate for Change: Environment, Health and Safety Report 2007. [February 20, 2010];2007 www.jti.com/cr_home/ehs.

- 91.Bunderson T, Jere Z, Chisui J, et al. Enhancing Rural Livelihoods in Malawi, Tanzania and Mozambique: Annual Report July 2007-June 2008: Total LandCare. 2008 July [Google Scholar]

- 92.This Day (Tanzania) African Farmers Turning Their Backs on Tobacco. [December 18, 2010];2008 www.thisday.co.tz/News/4908.html.

- 93.Scott P. Development of Improved Tobacco Curing Barn for Small Holder Farmers in Southern Africa. [June 1, 2009];2008 www.bioenergylists.org/scott_tobacco08.

- 94.Scott P. Development of Rocket Tobacco Barn for Small Holder Farmers in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. South Africa and Oregon: German Agency for Technical Cooperation; Programme for Basic Energy and Conservation in South Africa; and Aprovecho Research Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Imperial Tobacco Group. Case Studies: Fuel-Efficient ‘Rocket Barns’ in Malawi. [December 28, 2010];2010 www.imperial-tobacco.com/index.asp?page=318.

- 96.United Nations Development Program. Human Development Report 2009. New York: United Nations Development Program; 2009. http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2009/ [Google Scholar]

- 97.Arden D, editor. Nkhani Zaulere: the Malawi Chatterbox (newsletter) Malawi: Sep, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rosen N. No Carbon Disclosure Here, Thanks. Off-Grid. [July 2, 2009];2008 www.off-grid.net/2008/11/26/no-carbon-disclosure-here-thanks.

- 99.Dickinson P. Low Carbon Innovation Network; 2008. [July 1, 2009]. Paul Dickinson, Carbon Disclosure Project. www.carbon-innovation.com/discussion/viewtopic.php?t=383&sid=1ce3c30747fad09387bae0b90ba73200. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Carbon Disclosure Project. About the Carbon Disclosure Project. [5 May 2008];2009 www.cdproject.net/index.asp.

- 101.Carbon Disclosure Project. London, England Carbon Disclosure Project Working with Corporate Giants to Assess Co2 Emissions and Climate Disclosure from Supply Chains in 2008. [5 May 2008];2008 www.rb.com/DocumentDownload.axd?documentresourceid=35.

- 102.The Citizen [Tanzania newspaper] Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Farmers Benefit from Firm’s Initiative. [Jan 13, 2009];2008 www.thecitizen.co.tz/newe.php?id=7141.

- 103.Action on Smoking and Health. London Tobacco and the Environment. [December 28, 2010];2009 www.ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_127.pdf.

- 104.Carsan S, Holding C. Growing Farm Timber: Practices, Markets and Policies. Nairobi, Kenya: World Agroforestry Center; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Business Daily (Kenya) Planned Greening Law Threatens to Uproot Tobacco Growers. Nairobi: [Google Scholar]

- 106.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome Faostat Data. [May 20, 2010];2009 http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567#ancor.

- 107.Geist HJ. Global Assessment of Deforestation Related to Tobacco Farming. Tobacco Control. 1999;8:18–28. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mullan K, Kontoleon A. Benefits and Costs of Forest Biodiversity: Economic Theory and Case Study Evidence. Cambridge, United Kingdom: University of Cambridge; 2008. www.biodiversityeconomics.org/applications/library_documents/lib_document.rm?document_id=1143§ion_id=14. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Black R. British Broadcasting Corporation; 2008. [November 12, 2010]. London, England Nature Loss ‘Dwarfs Bank Crisis. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7662565.stm. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Eidt G. Modern Servitude in Transnational Tobacco Industries’ Practices in Southern Brazil [Presentation] Washington, D.C.: 13th World Conference on Tobacco OR Health; 2006. Jul 13, [Google Scholar]

- 111.Inter Press Service. Child Labor Rampant in Tobacco Industry. [March 1, 2009];1999 http://lists.essential.org/intl-tobacco/msg00033.html.

- 112.International Labor Organization. International Labor Organization; 2003. [1 Oct 2006]. Geneva Employment Trends in the Tobacco Sector: Challenges and Prospects. www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/sector/techmeet/tmets03/tmets-r.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ahsan A, Wiyono IN. An Analysis of the Impact of Higher Cigarette Prices on Employment in Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia: Demographic Institute, University of Indonesia; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Amigo M. Small Bodies, Large Contribution: Children’s Work in Tobacco Plantations of Lombok, Indonesia. Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology. 2010;11:34–51. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Syed R. Tobacco Production Jolted by War on Terror. Daily Times (Pakistan) [Google Scholar]

- 116.Benfica R, Zandamela J, Miguel A, de Sousa N. The Economics of Smallholder Households in Tobacco and Cotton Growing Areas of the Zambezi Valley of Mozambique. Ministry of Agriculture of Mozambique; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Foundation. Assessment of Child Labour in Small-Scale Tobacco Farms in Mozambique. [May 18, 2010];2006 http://www.eclt.org/activities/research/mozambique.html.

- 118.AIM News. Government Announces New Minimum Wages. [May 18, 2010];2010 www.clubofmozambique.com/solutions1/sectionnews.php?secao=business&id=18182&tipo=one.

- 119.Mongi H. Tobacco Farming and Seasonality in Tanzania: An Overview. Tabora, Tanzania: Tumbi Agriculture Research Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 120.De Muro P, Bocci R, Gorgoni S, et al. Competitve Commercial Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: Mozambique, Nigeria and Zambia Case Studies Social and Environmental Impact Assessment, Draft Report. Rome, Italy: Department of Economics, University of Rome; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Understanding Childrens Work. The Twin Challenges of Eliminating Child Labour and Achieving Efa: Evidence and Policy Options from Mali and Zambia. International Labor Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Bank; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chirwa J. International Labor Organization; 2009. [May 18, 2010]. Casualization of Labour in Zambia. http://ilsforjournalists.itcilo.org/en/course-area/previous-course-editions/final-stories/casualization-Zambia. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Beder S. Greenwash. In: Barry J, Frankland E, editors. International Encyclopedia of Environmental Politics. London: Routledge; 2001. www.uow.edu.au/arts/sts/sbeder/greenwash.html. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rose M, Colchester M. Green Corporate Partnerships: Are They an Essential Tool in Achieving the Conservationist Mission, or Just a Ruse for Covering up Ecological Crimes? Ecologist. 2004 July/August [Google Scholar]

- 125.Enoch S. A Greener Potemkin Village? Corporate Social Responsibility and the Limits of Growth. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism. 2007;18:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gewehr A. Tobacco Industry Uses Family Farmers as a Front Group: The False Debate in Brazil around Burley Tobacco and Flavourings. Bulletin. Novembe 15; [Google Scholar]

- 127.Phoon Z. We Walk the Talk When It Comes to CSR. New Straits Times (Malaysia) [Google Scholar]

- 128.Fauna and Flora International. Fauna & Flora International Welcomes Progress on Business and Biodiversity. [January 3, 2011];2010 www.fauna-flora.org/news/fauna-flora-international-welcomes-progress-on-business-and-biodiversity/

- 129.Payne A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development. Journal of Public Affairs. 2006;6:286–297. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Frey M, Wittman M. Gestao Ambietal E Desenvolvimento Regional: Uma Analise Da Industria Fumageira. eure (Chile) 2006;32:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hall R. Alternatives: Environmental ideas and action; 2009. [July 1, 2009]. 6 Steps to Cut the Greenwash. www.alternativesjournal.ca/articles/6-steps-to-cut-the-greenwash. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pearce F. Guardian; 2008. [July 1, 2009]. London The Great Green Swindle. www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/oct/23/ethicalbusiness-consumeraffairs. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rao P. Do Green Supply Chain Lead to Competitiveness and Economic Performance? International Journal of Operations and Production Management. 2005;25:898–916. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kim E-H, Lyon T. When Does Institutional Investor Activism Pay?: The Carbon Disclosure Project. Working paper: Stephen M Ross School of Business, University of Michigan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 135.US Securitues and Exchange Commission. Washington, DC Sec Charges Two Global Tobacco Companies with Bribery. [August 12, 2010];2010 http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-144.htm.

- 136.US Department of Labor. Notice of Final Determination Updating the List of Products Requiring Federal Contractor Certification as to Forced or Indentured Child Labor Pursuant to Executive Order 13126. [August 8, 2010];2011 www.dol.gov/federalregister/HtmlDisplay.aspx?DocId=24055&Month=7&Year=2010.