Abstract

The Meyerhoff Scholarship Program (MSP) is widely recognized for its comprehensive approach of integrating students into the science community. The supports provided by the program aim to develop students, primarily Blacks, into scientists by offering them academic, social, and professional opportunities to achieve their academic and career goals. The current study allowed for a rich understanding of the perceptions of current Meyerhoff students and Meyerhoff alumni about how the program works. Three groups of MSP students were included in the study: 1) new Meyerhoff students participating in Summer Bridge (n=45), 2) currently enrolled Meyerhoff students (n=92), and 3) graduates of the MSP who were currently enrolled in STEM graduate studies or had completed an advanced STEM degree (n=19). Students described the importance of several key aspects of the Meyerhoff Scholars Program: financial support, the Summer Bridge Program, formation of Meyerhoff identity, belonging to the Meyerhoff family, and developing networks - all of which serve to integrate students both academically and socially.

Keywords: Higher education, STEM, underrepresented minority, academic success, qualitative research

In the United States, growing attention is focused on students pursuing college and advanced degrees in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. This interest results from pressures to compete internationally, projected shortages in the STEM labor market, and difficulty retaining students in the STEM field (Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy, 2007, 2009; National Science Board, 2008a, 2008b; van Langen & Dekkers, 2005). Two ways to expand the available scientific labor pool are to invest in STEM education and to recruit students from historically underrepresented minorities (Building Engineering and Science Talent, 2004; Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy, 2007).

The literature on STEM fields highlights the overall low numbers of graduating scientists, and strikingly, the disparity between graduation rates of black students and their white and Asian counterparts. Among US citizens and permanent residents, Whites and Asians received 77% of STEM Bachelor's degrees, 74% of STEM Master's degrees, and 86% of STEM doctoral degrees in 2006. In that same year, Blacks received 9% of Bachelor's and Master's degrees and only 4% of Doctoral STEM degrees. Among all the STEM degrees granted in 2006, including nonresident aliens, Blacks received 8% of STEM Bachelor's degrees, 7% of STEM Master's degrees, but only 2% of STEM doctoral degrees (National Science Foundation, 2009).

Since 1988, the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC) has sought to redress these problems through the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program (MSP), a program aimed at increasing access to and success in STEM for black students. Using a multi-component approach that includes financial aid, recruitment, a summer bridge program, study groups, program values, program community, personal advising and counseling, tutoring, summer research internships, research experience during the academic year, faculty involvement, administrative involvement, mentoring, community service, and family involvement1, the program emphasizes the pursuit of a STEM PhD. Although the program opened to all races in 1996 (see Table 1 for program demographics), the focus remains on increasing black student access to and success in STEM education and has been extremely successful (Building Engineering and Science Talent, 2004; Gordon and Bridglall, 2004; Koenig, 2009; Maton, Hrabowski, & Schmitt, 2000; Maton, Sto. Domingo, Stolle-McAllister, Zimmerman, & Hrabowski, 2009; Summers, 2006).

Table 1. MSP Demographics (1988 – 2009), N = 964.

| Race/Ethnicity | Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blacks | 677 (70%) | Women | 474 (49%) |

| Whites | 141 (15%) | Men | 490 (51%) |

| Asians/Pacific Islanders | 123 (13%) | ||

| Latino/as and Native Americans | 23 (2%) | ||

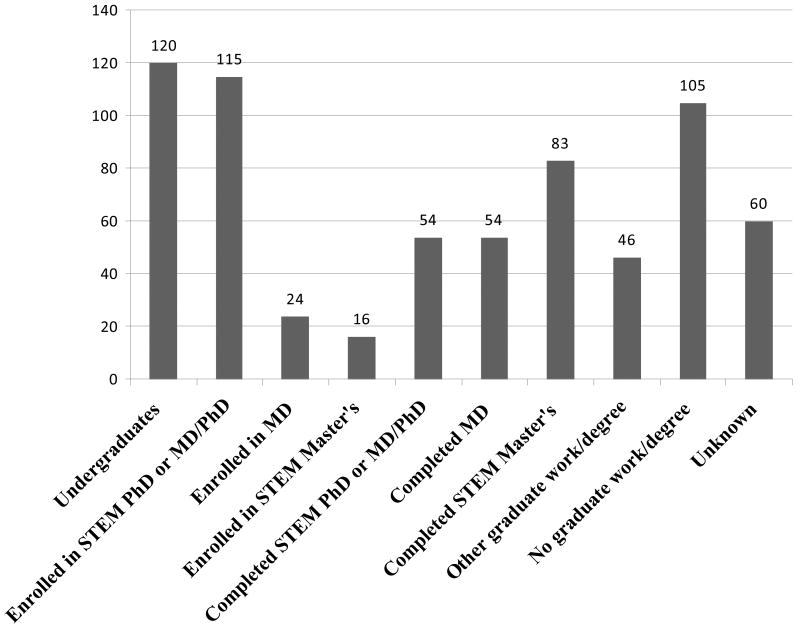

Black MSP students are twice as likely to graduate with a bachelors degree in STEM (Maton et al., 2000) and are five times more likely to go on to the PhD (Maton et al., 2009) than a comparison sample of similarly prepared students. Over fifty percent of black students in recent cohorts have pursued STEM PhDs or MD/PhDs (Maton et al., 2009). At this rate of PhD pursuit, the MSP at UMBC has been predicted to become one of the top baccalaureate-origin producers of black STEM PhD recipients nationwide (see Maton & Hrabowski, 2004). The current status of the 677 black students who have enrolled in the program between 1988 (the first cohort) and 2009 (the current cohort) are shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Current Status of Black Meyerhoffs, N=677.

However, little evidence is available showing why the program is successful. While quantitative research shows students in the first 15 cohorts (students entering the MSP between 1989 and 2003) rated financial scholarship, being part of the Meyerhoff Program community, Summer Bridge, study groups, and staff academic advising as particularly helpful (Maton et al., 2009), this study is the first in depth qualitative analysis of longitudinally collected data. This study fills a gap in the research by delineating the “how” and “why” and allows the students to speak for themselves. In particular, this research helps isolate the effective programmatic and social elements of the MSP.

Background

The MSP is designed to promote the success of black students in the sciences, particularly as it relates to earning a PhD or MD/PhD. Even among talented students, minority STEM majors face multiple barriers such as insufficient career information, an overwhelming course load, social and cultural isolation, and stereotype threat (Seymour & Hewitt, 2000; Steele, 1997; Wilson, 2000). To counteract these barriers, four areas are considered to be especially important to minority student success in the STEM majors: (1) academic and social integration, (2) knowledge and skill development, (3) support and motivation, and (4) monitoring and advising (cf. Maton & Hrabowski, 2004). A brief overview of the literature supporting each of the areas is presented below.

Academic and social integration

In his theoretical model, Tinto (1993) stresses the importance that academic and social integration holds for student success. Unfortunately, compared to white and Asian students, black students are more likely to have difficulty integrating both academically and socially on majority white campuses (Cole & Barber, 2003; Nettles, 1991). Triesman (1992) noted that many Blacks and Latina/os entered the university intending to pursue STEM degrees but very few completed even the entry-level courses. However, helping students to become both academically and socially integrated by creating a community of shared intellectual interest (Treisman, 1992), including a critical mass of academically talented peers of the same ethnicity can reduce isolation and optimize student outcomes (Fries-Britt, 2000; Gandara & Maxwell-Jolly, 1999).

Knowledge and skill development

The second area concerns student understanding of the foundational concepts and their development of critical abilities essential for achievement (Astin & Astin, 1992; Bonsangue & Drew, 1995; Springer, Stanne & Donovan, 1999; Treisman, 1992; Barlow & Villarejo, 2004). To promote knowledge and skill development it is critical that the concepts necessary for mastery are explicit (Bennet et al., 2004). This allows the learner to spend time and effort on learning tasks that promote the specific abilities most relevant to success (Bennet et al., 2004; Gordon and Bridglall, 2006). For example, utilizing effective study habits and accessing campus resources have both been associated with academic success (Bridglall & Gordon, 2004; Gandara & Maxwell-Jolly, 1999). Study groups have also been used to promote strong study habits as well as develop other abilities such as learning to have conversations concerning academic material and benefiting from the ideas of others (Bennet et al., 2004). Peer study groups also allow students to learn that academic success does not generally require solving problems quickly but persisting until the problem is solved (Bennet et al., 2004).

Support and motivation

Financial, family, faculty, and institutional support and internal motivation represent a third area important for minority student success. Due to the considerable amount of time required for STEM related coursework, it is difficult to achieve success in STEM majors if obligations such as outside work take up considerable time; thus, funding is critical for success (Callan, 1994; Garrison, 1987). Continuous support for STEM students is necessary due to the difficulty of STEM coursework and the appeal of less strenuous majors. Additionally, students across institutions describe science teaching styles as cold, elitist, and unsupportive (Newman, 1998). Counterbalancing the difficulties related to learning in the sciences requires strong supports including faculty involvement, meaningful research experiences, an academically focused peer group, involvement with university staff (including a mentoring relationship), and tutoring (Astin & Astin, 1992; Barlow & Villarejo, 2004; Doolittle, 1997; Fries-Britt, 1998; Grandy, 1998; May & Chubin, 2003; Seymour & Hewitt, 1997). Support systems, including peers, family, role models, and university staff, are especially important for minority students' persistence (Grandy, 1998; Herndon and Hirt, 2004; Fries-Britt, 2000). For example, Grandy (1998) found that students who indicated support from minority role models, support from peers in their ethnic group, and support from a dedicated minority staff at their college were more likely to commit to persisting in science by their sophomore year.

Monitoring and advising

The final area linked to student success in STEM is monitoring and advising, which helps STEM students select appropriate courses, plan for graduate study, manage their personal life, and establish standards and supportive relationships. For years, universities have provided minority students with university orientation sessions, often including course recommendations, ongoing academic advising, and monitoring (Treisman, 1983). Treisman (1983) found these types of interventions to improve minority students' math grades and increase retention. Consistent monitoring can help identify early warning signs of potential academic or personal problems, which may affect a student's progress. Advising can also benefit students by providing input concerning their strengths, weaknesses, and future careers (Gandara & Maxwell-Jolly, 1999; Seymour & Hewitt, 1997). Furthermore, being engaged with someone who can encourage and validate students' experiences and set standards is important for minority students (Terenzini et al., 1994)

Study Objectives

The specific aim of this study was to investigate how the MSP works and to answer the complex question, “What are the mechanisms through which the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program has an impact?” with a particular focus on the persistence of the Meyerhoff students in STEM. Although earlier quantitative studies have shown the effectiveness of the program and have identified important components (Bridglall & Gordon, 2004; Maton et al., 2000; Maton et al, 2009; Summers & Hrabowski, 2006), this research answers a call to understand the “why” and “how” of programs designed for minority students (Fries-Britt & Turner, 2002; Tsui, 2007). Specifically, we were interested in allowing the Meyerhoff students to speak for themselves and to identify the aspects of the program they found most beneficial.

Methods

We approached this research as a particularistic case study (Merriam, 1998) and used techniques from grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Corbin & Strauss, 2008) and Lincoln and Guba's (1985) “naturalistic approach.” We used focus groups as our method of data collection because they are a good tool for understanding specific college programs (Jacobi, 1991; Kaase and Harshbarger 1993) and they yield rich data, allowing researchers to gain understanding of different perspectives within a group process (Morgan, 1997; Taylor & Bogdan, 1998, Krueger & Casey, 2009). Because the Meyerhoff students are expert informants who are well-placed to describe the strengths and limitations of their experiences in the program, we used a purposeful sample of only current Meyerhoff students and graduates. Furthermore, to gain depth and richness of results, we met with some participants multiple times, having a total of 200 contacts through 30 focus groups.

Sampling and Data Collection

Three groups of MSP students were included in the study: 1) new Meyerhoff students participating in Summer Bridge (n=45), 2) currently enrolled Meyerhoff students (n=92), and 3) graduates of the MSP who were currently enrolled in STEM graduate studies or had completed an advanced STEM degree (n=19). Our sample reflects the current composition of the MSP with a majority black population (See Table 2). It is important to note that while not all the students in the program or in our sample are black, the program was designed for and retains its emphasis on promoting black student success in STEM. Each group is described in more detail below.

Table 2. Currently Enrolled Undergraduate MSP Demographics, N = 230.

| Blacks | 120 (52%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islanders | 46 (20%) |

| Whites | 53 (23%) |

| Latino/as and Native Americans | 11 (5%) |

Summer Bridge students

We conducted twelve face-to-face focus group interviews with two entering cohorts (entering 2006 & 2007) with a total of 45 students. Participants were randomly selected and the ethnic composition is as follows: 49% Black, 31% Asian/Pacific Islander, 18% White, and 2% Latina/o. Each focus group had between seven and eight participants, and we met with students at the very beginning and during the final week of Summer Bridge, a six-week orientation program to UMBC and the MSP. We focused specifically on the Summer Bridge students as the bridge component is one of the main ways through which Meyerhoff students are socialized regarding the academic and social expectations of the university (Maton et al., 2000) and recent reports have suggested the importance of this component for student outcomes (Bridglall and Gordon, 2004, Maton et al., 2009). Furthermore, these students are able to provide detailed information about their experiences in real time.

Current Meyerhoff students

We conducted face-to-face focus group interviews with 92 Meyerhoff participants currently enrolled at UMBC (entering cohorts 2002 – 2006). The students in this sample were randomly selected to participate with the exception of cohort 14 (2002), which was a convenience sample of volunteers from the entire cohort. The participants were 62% Black, 19% Asian/Pacific Islander, 17% White, and 2% Latina/o. We held a total of 15 focus groups with students during their freshman, sophomore, junior and senior years. Each group had between three and nine participants. We focused specifically on the current Meyerhoff students because they are able to discuss what they find helpful or challenging about their experience. Furthermore, by meeting with students at various points in their undergraduate careers, we are able to ascertain which aspects of the program are helpful at different time points and how student experiences change or remain the same over time.

Meyerhoff graduates

We conducted three focus groups with 19 graduates of the MSP. Participants in these groups ranged from newly entering doctoral students to PhDs (entering cohorts between 1989 and 2003) and were recruited through the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program office. The majority of the participants were Black (84%) with two Asian/Pacific Islanders (11%) and one Latina/o (5%). Given that an overarching goal of the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program is to increase the number of students obtaining advanced degrees in STEM fields, it was critical to evaluate the experiences of this sample as these participants were better able to recognize key factors that led them to pursue advanced STEM degrees and the aspects of the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program that influenced their educational endeavors. Although recall bias is a possibility, this group provided insight into the underlying mechanisms through which the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program had long term effects on their success.

These 30 groups, taken together, were chosen to highlight aspects of the program that affect students at various stages of their educational and professional careers. Conducting focus groups with each of the three groups of students was vital to assess students' perceived effects of the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program, both during and after undergraduate training.

Qualitative Data Analysis

The face-to-face focus groups were audiotaped, the tapes transcribed, and each participant was assigned a pseudonym. We asked open-ended questions regarding participants' perceptions of key aspects of the program and used participant responses to guide our subsequent questions. Questions focused on components of the program that were particularly helpful (or unhelpful), specific skills that students acquired during their participation in the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program, the processes through which the program had an impact on their STEM PhD and research career intentions, and their identity as a Meyerhoff Scholar. A team of four researchers, all of whom had either moderated or assisted during the focus groups, conducted the coding. Working together, we used techniques from Glaser and Strauss' grounded theory (1967), beginning with open coding to generate categories. During initial coding, sub-samples of the data set were redundantly coded by all researchers until we reached a consensus about definitions and interpretations of codes. A consistent understanding and utilization of codes helped ensure that our coding was accurate and reliable across researchers (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). After the initial phase, all the transcripts were coded by two researchers to ensure comprehensive and consistent coding. Throughout the process, we constantly revisited the data and codes to ensure accuracy and thoroughness and kept audit trails to make sure our findings were trustworthy (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Also, throughout the process we used the constant comparative method (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) and worked up from the data, using inductive analysis and making sure our coded data were heuristic and able to stand alone (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Results

The findings presented here focus specifically on key aspects of the program that students identified as being particularly helpful to them and which helped them succeed in STEM. Students described the importance of financial support, the Summer Bridge Program, the formation of a Meyerhoff identity, belonging to the Meyerhoff family, and developing networks.

Financial Support

“[I] definitely needed the money. But the program - what it stands for and what they actually do - is just amazing.”

Most participants said that one of the major factors influencing their decision to apply to and accept their offer from the MSP was financial. For many students, the “free tuition was very convincing,” and they were relieved that they would not have any financial debt from their undergraduate education. Additionally, many of them said the cost of a college education would be a burden for their families and that the financial support “takes the strain off the family.” Aside from allowing them entrance to an undergraduate program, students saw the ability to focus on their studies and complete their science major as the main benefit of their scholarships. Students recognized that, without financial support, the possibility of dropping out of school or science (because of the added cost) was a very real possibility.

Other areas in which students were able to see benefit from the financial support were in research and professional development. Funding they received through the program enabled them to participate in research internships as well as attend professional conferences. In addition to appreciating the scholarship at the undergraduate level, students also saw Meyerhoff as providing opportunities for graduate funding. A participant said he felt “…like I could probably go to any school I wanted to go to and study for my PhD [with funding].”

In general, students saw the financial aid as being critical, but they also saw the program as providing added value. Being highly successful students, most of the applicants had multiple financial offers. One student expressed a common sentiment: “I ended up going for the Meyerhoff Scholarship because it wasn't just a scholarship. The other ones were just money.” Another student elaborated, saying “…and the fact the program is catered towards getting you to your graduate degree goal: MD/PhD, whatever it might be. So it's not like it's just the money. It's kind of like it's catered towards getting you where you want to go…”

Summer Bridge Program

“Summer Bridge is where it all begins.”

During Summer Bridge, students are introduced to college level coursework and research opportunities, develop academic, social, and professional skills, and form the strong community that supports them throughout their undergraduate careers and beyond.

Students take two college classes for credit during Summer Bridge as well as seminars in either chemistry or physics. They also register for their fall classes and form an academic plan for their entire undergraduate career. With the assistance of program staff and older Meyerhoffs, students are guided in course and instructor selection as well as timing of courses and pacing. Students come out of Summer Bridge feeling prepared and ready to begin college:

Summer Bridge was really helpful too, because I feel like it gave us a head start in front of everybody else. We had a chance to get acclimated to the school and then to even college courses, because we took a couple of those. So I feel like when we got to school in the fall, some of the things that most freshmen fall prey to, like partying too much, not taking their classes seriously enough – no - we didn't have any of that problem because we had already been through a dry run almost.

Through site visits and guest speakers, students are introduced to research. They visit many premier research labs, meeting with investigators as well as agency directors. Through these visits, students gain an understanding of what research involves and they begin to think about their own undergraduate research. They plan internships and are able to form initial contacts to facilitate access to research sites. Importantly, students also begin to envision themselves as researchers and gain confidence that they are capable of managing a career in STEM. One student said, “…with the site visits, seeing everything and observing this is what they do in their careers, I feel kind of comfortable being able to do that so…It's kind of like, ‘Yeah, I can do this!’”

During Summer Bridge, students learn academic, social, and professional skills and, based on their reports, are able to apply them throughout their entire careers – from entering college into a profession. Academic skills involve study habits, study groups, note taking, and time management. One student pointed out that he corrected bad habits in addition to learning new skills:

I think that the Summer Bridge program has given us a lot of skills that we're going to need and it has also helped set any wrongs that have been within us throughout high school and before that. And I kind of think of it as…if a person breaks their bone and they never get it set the right way; it will grow the wrong way. In order to fix it, you have to break it again and set it the right way.

Social skills include conflict resolution, diversity appreciation, communication, and social leadership. Students also receive training in professional skills such as resume and application writing, professional dress and etiquette, and interview and public speaking skills. The social and professional skills were seen as particularly important to participants; many indicated that they would (and had) used them throughout their careers. One student recalled, “We learned so much - just life lessons - that being a professional or a researcher, anything, you're going to use that for a long time.”

Formation of a Meyerhoff Identity

“…I'm gonna' succeed, I'm gonna' get a PhD, I'm gonna' be involved with research in my future, and I'm gonna' contribute to my community. Those are like the four main things…that is what's going to happen for sure.”

Meyerhoff Scholars form a strong sense of identity which carries them beyond their undergraduate experiences. They refer to themselves as “Meyerhoffs” or, more commonly, “Ms.” This identity begins to form as early as Selection Weekend, a weekend designed for recruitment and Scholar selection. A graduate of the program said that during Selection Weekend

…when you see a Meyerhoff, you know it. And I think that's what Meyerhoff does. When you go through Selection Weekend and they pick you, they're saying, “Okay, you're the type of person we're looking for.” But they don't stop there; they groom you and they grow you into this person that everybody believes will be the best person for you. So, I think that goes a long way.

This process of development and growth as a Meyerhoff continues throughout the MSP and has consequences at both the individual and group level.

Individually, Meyerhoffs see themselves as highly successful and recognizable and, as one student put it, “I think being a Meyerhoff scholar means being the best.” Students recognize each other and are acknowledged by the larger campus community by their professional dress, behavior, and their goals. The program helps develop students' strong identity through high expectations. One student said, “It's expected that we do well in classes and it's expected that, you know, we look at research and look at grad schools and start things early…” Furthermore, by instructing students on appropriate professional dress and how to interact with others in professional settings, the program helps students develop a professional identity. By living up to their expectations and by employing their professional skills, students distinguish themselves as Meyerhoff. One student remarked:

You always want to carry yourself as a positive role model because that's what the…campus community, sees you as [sic]. And when somebody says, “He's a Meyerhoff,” that rings certain bells in people's heads. That means he or she's smart. That means they bought their books. That means that…they kind of have this high…perception of you…like, “He's a Meyerhoff. She's a Meyerhoff. So that means they must be doing well.”

The combination of academic, social, and professional interactions provides a feeling of group success and increases their belief that as a Meyerhoff, “It's automatically assumed that you're going to be successful.”

In addition to the feeling of inevitable success, students believe that identifying as Meyerhoff, both at UMBC and in the larger scientific community, opens doors and creates opportunities that would otherwise be unavailable to them. One student commented, “In the world of academia, it's good to associate as a Meyerhoff and everything. It's very helpful when you're networking with people that you mention that you're a Meyerhoff…” During the focus groups, Meyerhoff students shared their experiences of personally speaking with top tier university staff or faculty:

I was at Princeton this summer and I thought it was very funny because whenever one professor there introduced me to another [professor], or if we went on a tour of a company, it was automatically said, “This is Calista [pseudonym].” She's a Meyerhoff.” …It really, really surprised me how everybody knows what it is. And it means that [you] expect a lot from this person.

The Meyerhoff identity carries with it a reputation and expectations for the individual having the title. A participant commented, “To me, being a Meyerhoff Scholar means…representing more than just yourself now, representing 60 other people as well as the other 250 on the campus, and the name of Meyerhoff.”

Belonging to the Meyerhoff Family

“;…we call it the Meyerhoff family: we don't call it the Meyerhoff group. …at any other scholarship, I think, or any other school, it would just be a group. It would just be people who were all bounded by a financial support, but this is so much different. …It's more than that.”

The Meyerhoff program can be described not only as a support system but as a second family. The family feel of the program is one of the reasons students mentioned they chose the program and participants across all of the focus groups cited it as one of the most helpful aspects. Students spontaneously describe the program community as a family, referring to each other as brothers and sisters. When asked to identify the members of the family they identify the staff as parents, aunts, and uncles. In a student's words, “the program is your parent, your brother, your sister, your helpline, your friend, your counselor, all rolled in one.”

The Meyerhoff Family is a concept that is developed during Summer Bridge, solidified during the first year, and reinforced throughout the program. It provides an environment that focuses on group success and eliminates competition through the network of students who talk and confide among themselves, share the same goals, and possess similar skill sets. Additionally, participants in the MSP feel a sense of safety and security with each other and the staff, and a sense of mutual responsibility. One graduate of the program commented:

There was that common thread that everybody was struggling and it was okay. But you realized, “Hey! To succeed it's okay to reach out and we have these bonds now and we're all doing this as a group.” And it's not just YOU going forward and doing your thing and you're at the top of the mountain. You know everybody is there with you. And it made a difference.

Furthermore, the support received from the Meyerhoff Family was described as being especially helpful to students and their families of origin when transitioning to college during the freshman year and in STEM-related matters. A student said, “I think my parents were also sort of grateful because the program gave me someone to talk to. Neither of my parents have any idea about what I do; research-wise…”

This feeling of an extended and reliable community lasts beyond graduation from the program as graduate participants said that, even up to 20 years later, Meyerhoffs remain their sustaining community:

When I look back, when I got married, at least half of my groomsmen are Meyerhoff, I have god children that are from Meyerhoff – so most of my people that I'm closest to are either from UMBC or specifically the Meyerhoff program.

As with most families, everything is not perfect. Students say that this is one of the characteristics that defines it as a family. They point out that they may not always get along or agree with every Meyerhoff in their entering class, but that they feel a strong bond of affection and obligation to everyone. A student clarified, “…just like a family, you're going to fight with your brothers and sisters. You guys are going to have arguments. But at the end of the day, you still have the person's back… It's just like a relationship you'd have with siblings. There's hate and love and all that together.”

Developing Networks

“;…we have [a] responsibility, once we get out there and make it and get our MD/PhD or PhD, to become part of the networking system of the Meyerhoff program, and to put ourselves into positions of leadership to increase the minority representation in bio-medical research.”

The MSP and its scholars establish and cultivate an extensive network that helps students become connected to people who can make their educational and career goals a reality. Furthermore, many students cite the opportunities and networks provided by the MSP as one of the most helpful aspects of the program. By connecting current students and program alumni, sending scholars for campus and research lab visits during Summer Bridge, encouraging research internships in the first year, and by bringing scientists and graduate school representatives to campus, the MSP develops formal and informal as well as internal and external networks.

Formal networking activities begin as early as Summer Bridge with site visits to premier research sites and continue throughout students' careers at UMBC with “campus visits” by scientists and graduate schools. These activities connect the students to the outside world, show them research and graduate school opportunities, and establish the possibility of success. A student said, “So just knowing that we can get to go to all these important places kind of gives us the sense eventually we're going to be important enough to work there.”

While formal networking opportunities are effective mechanisms for making sure that students become aware of potential research sites or graduate schools, informal connections through the Meyerhoff staff provide students with further opportunities. One graduate of the program recalled:

It almost felt like you could go to Mr. Toliver's [the director's] office and there's a vault of internships, you'd just pick one and you'd probably find the one that fits you. Because it almost felt like he presses a button and he talks to the NSA or he talks to NIH and somebody is going to give you what you need. So, even if that never really was an option, thinking that it was – it was tremendous.

Not only does the MSP provide students with external networks, but they also provide students with effective internal networks which work both vertically and horizontally. The family feel of the program creates a collaborative environment where group success is valued and study groups are the norm. Students routinely offer their own expertise as well as seeking specific assistance from others in their cohort. Vertical networks exist where campus leadership, staff and older Meyerhoffs lend support, information, and resources to younger Meyerhoffs while the younger students actively seek the support of the former. A graduating senior reflected, “I've been at kind of both ends. Some ends, I'm helping the Meyerhoff program out; other times they're helping me. In the end, they are both wonderful.”

The organic network within the Meyerhoff Program, across cohorts, is remarkable due to its ability to facilitate placement of Meyerhoffs in various academic and occupational locations. A student said, “Wherever you go, there is going to be a Meyerhoff.” These informal mechanisms of reaching out to fellow Meyerhoffs, and being recognized as a Meyerhoff in the process, are utilized by the students:

They bring back people who are the best of the best for you to see. There are real people that were sitting in these chairs that are doing the things that you want to do and look at them now. And you can talk to them, you can contact them, you can email them, you can get them to do things for you because they're M-1s [1st cohort of Meyerhoffs] or M-2s or M-7s. They're people that have already been there.

The support of the Meyerhoff network seems particularly important to the black participants. Owing perhaps to the history of the program, the search for networks which are distinctly black seems to be strong among this underrepresented minority. One graduate of the program said:

You know, here I am, this African-American female…and…the chances of me finding someone that looks like me that has a PhD in Chemical Engineering are, like, zero to none. But [a woman] - who is also a Meyerhoff - she also has a PhD in Chemical Engineering. …NOW I know all these other African Americans that have these PhDs or all these other degrees and it's just like, “Wow! I know a black doctor!” And I didn't grow up seeing that. So, it's like you have this network of people that they're educated, they're making their connections, they're making choices in life, and they can help you.

Discussion

The elements of the MSP which students identified as critical help delineate important programmatic and psychosocial elements of this successful program. Additionally, each key aspect – financial support, Summer Bridge, the formation of a Meyerhoff identity, belonging to the Meyerhoff family, and developing networks – is encompassed by the four major factors identified in the research literature as leading to success: academic and social integration, knowledge and skill development, support and motivation, and monitoring and advising (Maton, Hrabowski & Schmitt, 2000; Maton & Hrabowski, 2004). The qualitative results fairly closely match prior quantitative research which found that financial support, being part of the Meyerhoff community, Summer Bridge, study groups, staff academic advising, and summer research opportunities were most beneficial (Maton et al., 2009) and provide insight as to how the MSP works. Furthermore, each key aspect identified by students fosters their academic and social integration into the program, an important element for retention and success (Tinto, 1993).

By providing financial support, the program frees students from financial concerns, allowing them to focus on their studies and achieve their goals. This same component was rated as providing the greatest benefit in a quantitative evaluation of the program and was rated 4.8 out of 5 on a Likert scale (Maton et al., 2009). Similar to other studies, participants emphasized the importance of the scholarship because it allows them to not only afford college, but to focus solely on their education (Callan, 1994; Garrison, 1987; Georges, 1999). Additionally, students were eager to point out that while the scholarship addresses the immediate financial concerns of college, it also provides them with additional support and motivation through the added value of a supportive community, the very real probability of obtaining graduate funding, and professional development opportunities.

Summer Bridge is a critical element of the MSP. During Summer Bridge, students are introduced to the program and its attendant values and expectations while simultaneously working to develop a solid academic, social, and professional foundation that will support them through their STEM careers. In a quantitative study, Maton et al. (2009) report that students rated Summer Bridge as one of the top three most beneficial components of the program. Summer Bridge includes all four elements that relate to student success – academic and social integration, knowledge and skill development, support and motivation, and monitoring and advising – and lays the foundation for key program components. Students form their identity as a Meyerhoff Scholar, become an integral part of the Meyerhoff family, and begin to develop professional networks. Summer bridge programs also offer an effective method of facilitating the transition and adjustment to university life and increase academic and social engagement (Garcia, 1991; Walpole et al., 2008). Overall, the orientation process has a direct effect on social integration and institutional commitment as well as a strong indirect effect on persistence (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1986).

Developing an identity as a Meyerhoff scholar and being part of the Meyerhoff family serve very important functions for students. Not surprisingly, being part of the Meyerhoff community earned a mean score of 4.6 out of 5 in a quantitative study of the MSP (Maton et al., 2009). From first contact with the MSP during Selection Weekend, students begin to form an identity as a Meyerhoff and come to understand that Meyerhoff Scholars are highly able and will meet with success. This early validation is an essential element for underrepresented minority student success (Terenzini et al., 1994). During Summer Bridge, living in close quarters on campus and participating in various bonding activities and rigorous academic course work, students develop an academic and social identity as a Meyerhoff as well as form a strong family structure. Because black students are more likely to experience isolation on majority white campuses and in science majors (Cole & Barber, 2003), developing a critical mass of high-achieving black students, and a strong identity as a Meyerhoff scholar, can be particularly powerful and help with student retention and success (Fries-Britt, 2000; Gandara & Maxell-Jolly, 1999; Seymour & Hewitt, 1997). Interestingly, Herndon and Hirt (2004) found that the black students in their study created fictive kin with other college students to increase their sense of community. While promoting the idea of a program, as a “family” may seem extreme, the concept may be culturally appropriate and functional for the black students involved in the Meyerhoff Scholars Program.

Furthermore, students in the Meyerhoff family are closely monitored and receive advising by staff members, which is another component that rated highly in the quantitative study (Maton et al., 2009). Consistent monitoring as well as advising and feedback can provide students with valuable input about their strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities (Gandara & Maxwell-Jolly, 1999; Seymour & Hewitt, 1997).

By participating in the extensive network available to them, students are able to integrate more fully into both the university and STEM. The academic, social, and professional network enhances students' knowledge and skill development and supports their academic and social integration. Perhaps due to the collective identity fostered through the years of living and learning together, the horizontal network that involves study groups and a collaborative environment is strong. The ability to utilize others' knowledge bases and create links through this network is critical for success as having a strong skill set and mastery of course content enhances student confidence and success (Astin & Astin, 1992; Bonsangue & Drew, 1995; Springer & Springer, 1999; Treisman, 1992). This resonates with the quantitative study of the program which reported that students rated study groups as one of the most beneficial aspects of the program (Maton et al, 2009). Furthermore, students and alumni, perhaps especially minority Meyerhoffs, appear to use the Meyerhoff network to navigate the complex terrain of persisting and succeeding in the sciences. As Meyerhoff students advance in their graduate programs and careers, reaching out to those who came before them, they gradually fulfill the role of mentors to those following them, providing an important, recognizable network of high-achieving Blacks which is so important for success (Fries-Britt, 1998).

While research experience is a focus among researchers investigating academic achievement and STEM, and has been identified as an effective method of providing students with skills, knowledge, and professional relationships (Bauer & Bennett, 2003; BEST, 2004; Carter, Mandell & Maton, 2009; Hunter et al., 2007; Lopatto, 2008), participants in this study did not spontaneously mention research experience, per se, as an important aspect of the program. This differs from the 2009 quantitative study in which students rated summer research as highly beneficial (Maton et al., 2009). In the quantitative study, students were presented with a list of program components and asked to rate them, whereas in this study, the most helpful aspects of the program were generated by the students without prompting by researchers. While students did not mention “summer research” specifically, they did consistently mention “opportunities” and “making contacts” and discussed their research within the context of the networking system of the MSP. The concept of summer research seems to be an extension of the networking opportunities available to them. It also may be that many students view their research experience as simply part of their academic pursuits, and not as a distinct component of the program like Summer Bridge and Meyerhoff study groups.

The key components that the students identified in this paper fit nicely with Tinto's (1993) theory of student departure which emphasizes the importance of both academic and social integration for student success and persistence to a college degree. Tinto also stresses the need to break away from past associations and traditions, an assertion that has met with criticism from those working in the field of minority achievement (Guiffrida, 2006). According to the critics, this aspect of the theory may be harmful as it ignores bicultural integration, or the ability of minority students to succeed in higher education while being part of the minority and majority cultures. Some critics also contend that minority students' motivational orientation for educational success differs from those of their white peers, and that accordingly there is a need to recognize minority community and familial connections more prominently. In contrast, in the Meyerhoff Scholars Program, students are required to live on campus, which ensures a distance from their families and communities. The students' families of origin are then supplemented with a surrogate family, the Meyerhoff Scholars Program itself—complete with brothers and sisters and parental figures. While complementing their family of origin and other community connections, this new Meyerhoff family serves to strengthen the students' connection to the academic community and bonds them more closely to the university. At the same time, the program actively involves students' parents in the program through a Meyerhoff parent association.

The Meyerhoff Scholarship Program has been successful at building a foundation for students, introducing them to the Meyerhoff culture through Summer Bridge, creating a Meyerhoff identity, providing a family atmosphere, and developing a network - all of which serve to integrate students both academically and socially. This integration which values black students for their abilities and respects their cultural heritage allows students to fit into the UMBC and STEM community, facilitating their retention in the sciences. The MSP provides students with the necessary ingredients for the successful navigation of the terrain of scientific life within a smaller structure that is culturally and socially adaptive to minority experience. That is, the MSP appears to successfully provide a sense of identity and support while simultaneously providing very challenging and high standards for individual student success. The development of a strong and supportive community, with a majority of Blacks and a focus on that population, and the integration of challenging academic and social norms, fosters a sense of belonging, validation, and meaning for the Meyerhoff students.

Limitations

The current study allowed for a rich understanding of the perceptions of Meyerhoff students about how the program works. We acknowledge, however, certain limitations that this study has relative to potential selection bias and the generalizability of the findings to the earlier cohorts that have not been part of the sample. In spite of careful sampling in a random fashion, and although we heard criticisms of aspects of the program, it is not certain whether those who accepted our invitation to become part of the focus groups were more inclined to view the program in a positive light than those who did not. Attempts were made to reduce this potential bias by using skilled moderators, reiterating among the participants that both positive and negative comments about the program are welcome, and that confidentiality will be observed.

As the sample is mainly comprised of later cohorts (with the exception of earlier cohorts in the graduate sample), the generalizability of the findings among the earliest cohorts may be limited. Although participants may be well aware of the history of the program, they did not have the first-hand experience of those who came before them during the first few years of the MSP, thus it could be possible that program components were refined over time.

Future Research

Future research should focus on truly mixed method investigations of program components that are effective for STEM students. Use of concurrent quantitative and qualitative data collection methods, perhaps on a semester-by-semester basis, would give researchers real time information on effective programmatic interventions. Other research efforts might focus on graduate students to discover what supports them in their pursuit of the STEM PhD. Understanding which interventions at the undergraduate level (and even earlier) remain effective as students pursue graduate work is essential for effectively broadening minority participation in STEM disciplines.

Conclusion

Several key aspects of the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program were identified in this study: financial support, Summer Bridge, the formation of a Meyerhoff identity, belonging to the Meyerhoff family, and developing networks. All of these aspects map to factors we know contribute to academic achievement. These programmatic and psychosocial elements provide a brief yet comprehensive picture of the holistic approach the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program takes to increasing minority student achievement. Furthermore, the program has been successful in graduating a high number of STEM majors and many of these students have gone on to pursue doctoral degrees in the sciences. It appears that the supports the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program provides have far reaching effects. Future research should focus on understanding which of these aspects is most critical to long-term academic success and how these benefits can be transferred to other settings and populations.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by Grant Number 5R01GM075278-3 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of NIGMS or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

See Bridglall & Gordon (2004) for a detailed description of the program.

References

- Astin AW. What matters in college: Four critical years revisited. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Astin AW, Astin HS. Undergraduate science education: The impact of different college environments on the educational pipeline in the sciences. Final report. 1992 Available at http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/13/1b/e8.pdf.

- Bauer KW, Bennett JS. Alumni perception used to assess undergraduate research experience. The Journal of Higher Education. 2003;74:210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A, Bridglall B, Cauce A, Everson H, Gordon E, Lee C, et al. All students reaching the top: Strategies for closing academic achievement gaps. A report of the National Study Group for the Affirmative Development of Academic Ability. North Central Regional Educational Laboratory 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Berg BL. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 5th. Pearson Education Inc.; Boston: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brazziel ME, Brazziel FB. Factors in decisions of underrepresented minorities to forego science and engineering doctoral study: A pilot study. Journal of Science Education and Technology. 2001;10:273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bridglall BL, Gordon EW. Creating excellence and increasing ethnic minority leadership in science, engineering, mathematics and technology: A study of the Meyerhoff Scholars program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Authors; 2004. Unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsangue MV, Drew DE. Increasing minority students' success in calculus. In: Mnges RJ, Gainen J, Willemsen EW, editors. Fostering Student Success in Quantitative Gateway Courses: Vol 61. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1995. pp. 23–33. Series Ed., Vol Eds. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SV. The preparation of minorities for academic careers in science and engineering. In: Campbell G, Denes R, Morrison C, editors. Access denied: Race, ethnicity, and the scientific enterprise. NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 239–268. [Google Scholar]

- Building Engineering and Science Talent. Bridge for All: Higher education design principles to broaden participation in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. 2004 Retrieved on January 15, 2010 from http://www.bestworkforce.org/PDFdocs/BEST_BridgeforAll_HighEdFINAL.pdf.

- Callan P. Equity in higher education: The state role. In: Justiz M, Wilson R, Bjork L, editors. Minorities in higher education. Phoenix AZ: American Council on Education and Oryx Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cole S, Barber E. Increasing faculty diversity: The occupational choices of high-achieving minority students. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JA, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd. Los Angeles: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy. Rising above the gathering storm: Energizing and employing America for a brighter economic future. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy. Rising above the gathering storm two years later: Accelerating progress toward a brighter economic future. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fries-Britt S. Moving beyond Black achiever isolation: Experiences of gifted black collegians. The Journal of Higher Education. 1998;69:556. [Google Scholar]

- Fries-Britt S. Identity development of high-ability black collegians. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 2000;82:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fries-Britt S, Turner B. Uneven stories: Successful black collegians at a black and a white campus. Review of Higher Education: Journal of the Association for the Study of Higher Education. 2002;25:315–330. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia P. Summer bridge: Improving retention rates for unprepared students. Journal of the Freshman Year Experience. 1991;3(2):91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison HH. Undergraduate science and engineering education for Blacks and Native Americans. In: Dix LS, editor. Minorities: Their underrepresentation and career differentials in science and engineering. Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon E, Bridglall B. Nurturing talent in gifted students of color Conceptions of giftedness. 2nd. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 120–146. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon E, Bridglall B. Affirmative development: Cultivating academic ability. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.; 2006. (Critical issues in contemporary American ducation Series). [Google Scholar]

- Grandy J. Persistence in science of high-ability minority students: Results of a longitudinal study. Journal of Higher Education. 1998;69:589–620. [Google Scholar]

- Herndon M, Hirt J. Black students and their families: What leads to success in college. Journal of Black Studies. 2004;34(4):489–513. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi M. Focus group research: A tool for the student affairs professional. NASPA Journal. 1991;28:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kaase KJ, Harshbarger DB. Applying focus groups in student affairs assessment. NASPA Journal. 1993;30:284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig R. U.S. Higher Education: Minority retention rates in science are sore spot for most universities. Science. 2009;324:1386–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.324_1386a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 4th. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lopatto D. Exploring the benefits of undergraduate research: The SURE survey. In: Taraban R, Blanton RL, editors. Creating effective undergraduate research programs in science. NY: Teacher's College Press; 2008. pp. 112–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI, Hrabowski FA., III Increasing the number of African American PhDs in the sciences and engineering: A strengths-based approach. The American Psychologist. 2004;59:547–556. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI, Hrabowski FA, III, Schmitt CL. African American college students excelling in the sciences: College and post-college outcomes in the Meyerhoff Scholars Program. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 2000;37:629–654. [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI, Sto. Domingo MR, Stolle-McAllister KE, Zimmerman JL, Hrabowski FA., III Enhancing the number of African Americans who pursue STEM PhDs: Meyerhoff Scholarship Program outcomes, processes, and individual predictors. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering. 2009;15:15–37. doi: 10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.v15.i1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May GS, Chubin DE. A retrospective on undergraduate engineering success for underrepresented minority students. Journal of Engineering Education. 2003 January;:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- National Science Board. Freshmen intending S&E major, by sex, race/ethnicity, and field: Selected years, 1985-2006. Science and Engineering Indicators 2008. 2008a Retrieved July 22, 2008, from http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind08/append/c2/at02-15.pdf.

- National Science Board. Science and Engineering Indicators, 2008. Two. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation; 2008b. [Google Scholar]

- National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics. Detailed Statistical Tables NSF 10-300. Arlington, VA: 2009. Science and Engineering Degrees, by Race/Ethnicity of Recipients: 1997-2006. Mark K. Fienegen, project officer. Available at http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf10300/ [Google Scholar]

- Nettles MT. Racial similarities and differences in the predictors of college student achievement. In: Allen WR, Epps E, Haniff NZ, editors. College in Black and White. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1991. pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. Rapprochement among undergraduate psychology, science, mathematics, engineering, and technology education. American Psychologist. 1998;53(9):1032–1043. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.9.1032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella ET, Terenzini PT. Orientation to college and freshman year persistence/withdrawal. Journal of Higher Education. 1986;57(2):155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour E, Hewitt NM. Talking about leaving: Why undergraduates leave the sciences. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Springer L, Stanne ME, Donovan SS. Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research. 1999;69:21–51. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape the intellectual identities and performance of women and African-Americans. American Psychologist. 1997;52:613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers MF, Hrabowski FA., III Preparing minority scientists and engineers. Science. 2006;311:1870–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.1125257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SJ, Bogdan R. Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource. 3rd. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Terenzini PT, Rendon LI, Upcraft ML, Millar SB, Allison KW, Gregg PL, Jalomo R. The transition to college: Diverse students, diverse stories. Research in Higher Education. 1994;35:57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto V. Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. 2nd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman PU. Improving the performance of minority students in college-level mathematics. Innovation Abstracts, 5. 1983 Retrieved on April1, 2010 from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/31/ec/d8.pdf.

- Treisman U. Studying students studying calculus: A look at the lives of minority mathematics students in college. The College Mathematics Journal. 1990;23:362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui L. Effective strategies to increase Diversity in STEM fields: A review of the research literature. The Journal of Negro Education. 2007;76:555–581. [Google Scholar]

- van Langen A, Dekkers H. Cross-national differences in participating in tertiary science, technology, engineering and mathematics education. Comparative Education. 2005;41(3):329–350. [Google Scholar]

- Walpole MB, Simmerman H, Mack C, Mills JT, Scales M, Albano D. Bridge to success: Insight into summer bridge program students' college transition. Journal of the First Year Experience & Students in Transition. 2008;20(1):11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. Barriers to minority success in college science, mathematics, and engineering programs. In: Campbell G, Denes R, Morrison C, editors. Access denied: Race, ethnicity, and the scientific enterprise. NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]