Abstract

Worldwide, contemporary measures of the success of health development programs have been mostly in terms of the reduction of mortality and morbidity as well as increasing longevity. While these goals have yielded much-needed health improvements, the subjective outcomes of these improvements, as experienced by individuals and the communities, have not been considered. Bhutan, under the overarching policy of Gross National Happiness, has provided due consideration to these subjective indicators. Here, we report on the current status of health and happiness in Bhutan as revealed by conventional objective indicators and subjective Gross National Happiness indicators. The current literature on health in Bhutan in relation to the Gross National Happiness Survey conducted by the Centre of Bhutan Studies has been reviewed. Bhutan has made great strides within a short period of modernization, as shown by both objective and subjective indicators. Tremendous challenges lie ahead to achieve the ultimate goal of health and happiness, and how Bhutan articulates its path to modernization may be a lesson for the rest of the world.

Keywords: Bhutan, happiness, health, indicators

Introduction

The Kingdom of Bhutan is a mountainous land-locked country in the eastern Himalayas, lying between the Tibetan Plateau in the north and the Indian plains in the south. It covers an approximate area of 38,394 km2, spanning roughly 150 km north to south and about 300 km east to west, with an elevation ranging from about 160 m above sea level in the south to more than 7500 m above sea level in the north. About 70% of the total land is covered with forest. The population enumerated in 2005 is 634,982 persons, of whom 333,595 are male and 301,387 are female.1 According to the World Bank, the gross national income per capita was USD 2020 in 2009.2

Bhutan started its modern health system in 1961 with two hospitals, two doctors, and two nurses. During that period, the prevalence rates for tuberculosis and leprosy was up to 15 per 1000 population, and about 80% of the female population had goiter. Other diseases, such as diarrhea, venereal disease, and malaria were also rampant.3,4

Bhutan became a signatory to the Alma-Ata declaration in 1978. Since then, Bhutan has ascribed the utmost importance to the health of its people. In addition, Bhutan adopted Gross National Happiness (GNH), which puts the happiness of the population at the core of developmental policies. Article 9 of the Constitution of Bhutan prescribes that “the state shall strive to promote those conditions that will enable the pursuit of Gross National Happiness.” This noble philosophy has been debated in greater detail in various international seminars led by the Centre for Bhutan Studies and attracted much international attention.5

Happiness as a developmental goal

Happiness varies across individuals and cultures,6 despite being an ultimate goal for individuals in all human societies. This concept is embedded in most religions and cultures, but in contemporary times, the pursuit of happiness has been translated into an unwavering pursuit of economic growth.7 The concept of health and well-being has been the subject of discussion for a long time, and numerous studies have been conducted on this subject.8–13 In recent years, psychologists and social scientists have made strides in research on subjective well-being, and some of the major achievements have been the development of models and measurement of subjective well-being.14–18 Despite much progress, it has been highlighted that there is a need for more studies on the subject of health and happiness.11,19 Further, despite the increasing amount of literature on health and well-being, happiness as a national goal has not always been pursued.

The fourth king of Bhutan, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuk, in 1974, realizing the mismatch in the trajectory of growth-oriented market economics as a developmental philosophy, formulated the concept of GNH. To this end, development should serve the total well-being of the people and economic development is only the means to achieve it.20 In Bhutan, happiness is considered as a public good, and it is the responsibility of the government to create an enabling environment for the pursuit of GNH, as enshrined in the constitution.21

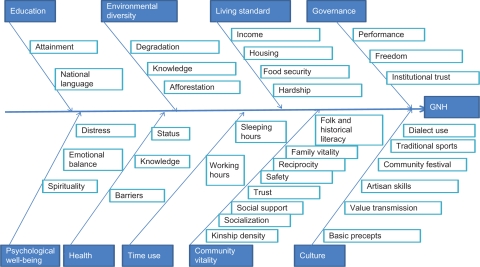

GNH in Bhutan is based on four principles, ie, sustainable and equitable economic development, conservation of the environment, preservation and promotion of culture, and good governance. The Centre for Bhutan Studies, as mandated by the Royal Government of Bhutan, has developed a GNH index under nine domains (Figure 1).21 As part of the government initiative of the GNH index, the Centre for Bhutan Studies conducted a survey based on these domains in December 2007–March 2008 in 12 districts of Bhutan.22

Figure 1.

Gross National Happiness and its domains: a deductive model.

This article reviews the current state of Bhutan’s health and GNH, as indicated by both objective and subjective measurements. As far as we know, this is the first such report on the health status of Bhutan. This research may be of use for health planners, policymakers, and future researchers in this field.

Methods

For the conventional objective indicators, the literature was searched using terms “Bhutan” and “health” and combinations of these two terms. We searched in the Directory of Open Access Journals, Google Scholar, PubMed, open J-Gate, ScienceDirect, and the Social Science Research Network. We also searched various web publications and reports maintained at the National Portal of Bhutan (http://www.bhutan.gov.bt/government/index_new.php), Ministry of Health website (http://www.health.gov.bt/), and the Centre of Bhutan Studies website (http://www.bhutanstudies.org.bt/). In addition, we manually searched the reports, including consultancy assignment reports and reviews done for the Ministry of Health at the Ministry of Health Library and within the ministry. News reports and Aide-Memoire were also examined.

For the subjective evaluation of health, we focused on the GNH indicator survey results conducted by The Centre of Bhutan studies (available at http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/, accessed and downloaded on January 21, 2010). We mainly reviewed two domains of the GNH, namely health and psychological well-being. This GNH survey was carried out from December 2007 to March 2008 in 12 districts and included 950 respondents. The methodology and survey tools, including the findings from other domains, can be viewed at the above mentioned website. The literature was selected based on relevance and information extracted and reviewed by the first author, which was further examined and reviewed by the other authors.

Results

Despite availability of ample information about health and well-being in general, our search yielded a paucity of published information on health and GNH in Bhutan. Hence, official websites, government and international reports, and consultancy reports constituted the bulk of the information discussed in this paper.

Discussion

Article 9 of the Constitution of Bhutan states that “the state shall provide free access to basic public health services in both modern and traditional medicine.” This constitutional responsibility is delivered through a three-tiered health system, ie, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels that provide preventive, promotive, and curative services via 31 hospitals, 178 basic health units, and 654 outreach clinics scattered throughout all 20 districts and 205 subdistricts of Bhutan.23,24 These broad-based health systems are required, considering that 69.1% of the Bhutanese population lives in rural areas. There are no private medical facilities, and all treatment, including referrals to facilities outside the country, is provided free by the government. Currently, the government is spending about 5.7% of its total planned budget on health.25 This has resulted in a noticeable result for all health indicators (Table 1).23,24,26 Bhutan eliminated iodine deficiency disorder in 200327 and leprosy in 1997, and achieved universal childhood immunization in 1991.24 In 2004, Bhutan became the first country in the world to ban the sale of tobacco.28 The incidence of malaria also decreased from 12,591 cases in 1999 to 972 cases in 2009.29

Table 1.

Core demographic and health indicators in Bhutan

| Indicators |

Years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1994 | 2000 | 2005 | 2008 | |

| Total fertility rate (births per woman) | – | 5.6 | 4.7 | 3.0 | 2.4 |

| Population growth rate | 2.6 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Infant mortality rate/1000 live births | 102.8 | 70.7 | 60.5 | 56 | 49.3 |

| Maternal mortality ratio/100,000 live births | 770 | 380 | 260 | 440 | – |

| Life expectancy in years | – | 49 | 66 | 65 | 66 |

Bhutan has already achieved some of its millennium development goals, including access to improved water and sanitation, and is on track to achieve the remaining goals.30,31 These achievements were commended by the international community, when the 5th World Health Assembly awarded its prestigious Sasakawa Health Award to the Monggar Health Services Development Project in 1997, and when the World Health Organization awarded its fiftieth anniversary award for primary health care to Bhutan in 1998.32 Although the Royal Institute of Health Sciences currently focuses on training nurses, paramedics, and public health practitioners, there are future plans to upgrade this into a nursing and medical college to meet the human resources required in Bhutan.33,34 These achievements were also acknowledged during the joint Bhutan-Danish International Development Agency health sector review.35

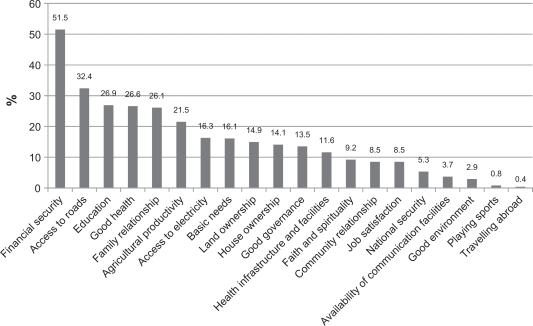

Sources of happiness for the Bhutanese population varied from financial security to travelling abroad (Figure 2).36 On a 10-point scale (1 = not a very happy person, 10 = a very happy person), the average happiness score was 6.2 for Bhutan residents. Both good health and access to the health infrastructure and facilities are considered important sources of happiness.36 In a GNH indicator survey, 25.5% of respondents reported their health as excellent/very good, 64.1% reported it as good, and 66.3% of men and 58.5% of women reported not having any mental or physical illness during the 30 days preceding the survey. Conversely, 10.7% of men and 13.4% of women reported illness lasting 14 days or more during the same time period. Long-term disability was reported by 12.6% of rural respondents and 4.4% of urban respondents. Happy life years, calculated as the product of life expectancy and happiness score, resulted in 40.7 years for Bhutan.37

Figure 2.

Twenty sources of happiness for Bhutanese people.

For government performance in the 12 months preceding the survey, ratings of excellent were given by 73% of respondents for improving education, 72% for improving health services, 67% for protecting the environment, 57% for providing electricity, 49% for providing roads, 38% for fighting corruption, 38% for creating jobs, and 37% for reducing the income gap between rich and poor.38

Traditional Bhutanese medicine, known as “gso-ba-rig-pa,” is well integrated into the modern health care system.33 This form of traditional Buddhist medicine, currently practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, and Bhutan, dates back about 2500 years.39 In Bhutan, this traditional service is available in all districts. In most districts, these two systems are located in the same hospital and people can choose either type of service to use. In addition, other forms of traditional remedies are also practiced. The survey showed that 78.1% of respondents consulted an astrologer for matters related to them and their family, with 13% of respondents consulting an astrologer as a first contact during an illness.37

Other culturally related health determinants included in the GNH survey were consumption of alcohol and chewing of “doma” (areca nut and betel leaf with a dash of lime giving a red color when chewed). Alcohol and doma are an integral part of Bhutanese tradition and culture, and are served during most ceremonies and rituals. These traditionally valued commodities may be consumed in excessive amounts causing untoward health effects. As per the annual health report, alcohol is one of the top ten causes of death in Bhutan.24 The GNH indicator survey showed that 61.5% of respondents reported consuming alcohol at some point of time, with 17.7% of drinkers reporting that they had been drinking most of the time in the previous 12 months. In a similar manner, 75.8% reported chewing doma at some point in time, of whom 22.7% reported chewing doma on a daily basis. In contrast, only 17.6% of respondents reported having smoked tobacco at some point in their lives. Tobacco smoking is against Buddhist teaching. This indicates that health risk behaviors which are culturally acceptable are more prevalent than those that are culturally proscribed.

Income has a strong correlation with happiness, although studies from developed countries show that income has a saturation point and does not correlate with an increase in income.40 In economic terms, Bhutan has progressed from being one of the poorest countries in the 1980s to becoming one of the middle income economies of the world,41 with an annual average growth rate of 7.5% in its gross domestic product.42 However, Bhutan is still a poor state, with 23.2% of the population living below the poverty line, and per capita consumption of USD 24 per person per month.42 The socioeconomic disparity is evident, with the richest 20% of the national population consuming 6.7 times more than the poorest 20%. There is also an increasing trend of mental disorders, with increasing numbers of young people suffering from stress and anxiety-related disorders.43 The GNH indicator survey found that disparities prevail in all categories of socioeconomic status for most variables measured. The survey report showed that male gender, higher educational level, strong family bonds, good health, lack of suicidal tendency, and participation in sporting and religious activities, were some of the factors contributing to happiness. While women have a longer life expectancy, men are found to be healthier, less disabled, and happier than women. These finding are in general consistent with those of other studies.18

There is no pharmaceutical company in Bhutan, and medicines are centrally procured and distributed to the remote health centers every year. The availability of over 90% of essential drugs is maintained throughout the year.44 The Health Trust Fund was created in 1997 to sustain accessibility of these essential services by the people, with a current fund accumulation of USD 23.7 million.45 This would augment the funding requirement for sustainable supplies of essential drugs and vaccines to fulfill the constitutional mandate of providing free health care.

Sustainable development is defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” encompasses social, economic, and environmental dimensions.46 The values generated from these important concepts can be used for active promotion of health and pursuit of happiness. Environmental preservation is one of the foundations of GNH, and in Bhutan, the constitution mandates that a minimum of 60% of land area must have forest coverage. Ecological degradation, ecological knowledge, and afforestation variables are measured under the environmental diversity domain.

For sustainable and healthy development promoting happiness of the nation, all four dimensions of the GNH needs to be addressed in a balanced and integrated manner, and measured periodically as a developmental yardstick. Only then can health, happiness, and development flourish harmoniously.

Conclusion

Bhutan’s strides in improving the health and happiness of its population, as suggested by various indicators, is commendable. The GNH indicator survey was taken when the country was in transition to full parliamentary democracy, and these baseline indicators can be used as a developmental yardstick. Despite the achievements, as indicated by both subjective and objective measures, much still needs to be done to improve GNH in Bhutan. This includes elimination of poverty, narrowing the socioeconomic gap, fighting emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, and halting the increasing trend of mental and lifestyle-related diseases. Therefore, the manner in which the health system is remodeled to address these challenging issues within the context of the growing expectations of the modern Bhutanese population will affect happiness indicators, and how Bhutan strives for economic growth without compromising the well-being of its people could epitomize the modern developmental paradigm.

Acknowledgments

The report was funded by the United Nations Children’s Fund/United Nations Development Programme, and the World Bank/World Health Organization program for research and training in tropical diseases. The authors extend their gratitude to The Commission on Higher Education, Ministry of Education of Thailand, and Royal Government of Bhutan for supporting this research.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.National Statistics Bureau . Statistical Year Book of Bhutan 2009. Thimphu, Bhutan: National Statistics Bureau, Royal Government of Bhutan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Bank South Asia regional data. 2011. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD. Accessed April 21, 2011.

- 3.Berkeley JS. Primary medical care in Bhutan. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1979;29(206):530–533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward M, Jackson F. Medicine in Bhutan. Lancet. 1965;285(7389):811–813. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(65)92976-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates W. Gross National Happiness. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature. 2009;23(2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu L, Gilmour R, Kao S-F, et al. Two ways to achieve happiness: when the East meets the West. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30(7):1161–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald R. Towards a new conceptualization of Gross National Happiness and its foundations. Journal of Bhutan Studies. 2005;12:23–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backman G, Hunt P, Khosla R, et al. Health systems and the right to health: an assessment of 194 countries. Lancet. 2008;372(9655):2047–2085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61781-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helliwell JF. Well-being, Social Capital And Public Policy: what’s new? Cambridge, MA: NBER; 2005. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No W11807. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w11807. Accessed November 21, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hills P, Argyle M. The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: a compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;33(7):1073–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekhet AK, Zauszniewski JA, Nakhla WE. Happiness: theoretical and empirical considerations. Nurs Forum. 2008;43(1):12–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2008.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perneger TV, Hudelson PM, Bovier PA. Health and happiness in young Swiss adults. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(1):171–178. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015314.97546.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker SS, Schimmack U. Validity of a happiness implicit association test as a measure of subjective well-being. J Res Pers. 2008;42(2):490–497. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diener ED, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: health and Well-Being. 2011;3(1):1–43. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durayappah A. The 3P model: a general theory of subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2010:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallup and Healthways Wellbeing Index. 2008. Available from: http://www.well-beingindex.com/. Accessed Janaury 19, 2010.

- 17.Kim-Prieto C, Diener E, Tamir M, Scollon C, Diener M. Integrating the diverse definitions of happiness: a time-sequential framework of subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2005;6(3):261–300. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian SV, Kim D, Kawachi I. Covariation in the socioeconomic determinants of self rated health and happiness: a multivariate multilevel analysis of individuals and communities in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(8):664–669. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.025742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross N. Health, happiness, and higher levels of social organisation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(8):614. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.031732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choden T, Kusago T, Shirai K. Gross National Happiness and Material Welfare in Bhutan and Japan. 2007. Available from: http://www.bhutanstudies.org.bt/pubFiles/GNH-MaterialWelfare-part1.pdf. Accessed November 2010.

- 21.Ura K. Explanation of GNH Index. 2008. Available from: http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/gnhIndex/intruductionGNH.aspx. Accessed January 25, 2009.

- 22.Centre of Bhutan studies Gross National Happiness. 2008. Available from: http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/gnhIndex/intruductionGNH.aspx. Accessed November 21, 2010.

- 23.National Statistical Bureau . Thimphu, Bhutan: National Statistical Bureau; 2005. Population and Housing Census. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health . Kawajangsa, Bhutan: Ministry of Health, Bhutan; 2009. Annual Health Bulletin. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross National Happiness Commission Tenth Five Year Plan (2008–2013) Available from: http://www.planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/upload/Bhutan/Bhutan_TenthPlan_Vol1_Web.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2011.

- 26.Ministry of Health . Kawajangsa, Bhutan: Ministry of Health, Bhutan; 2000. National Health Survey 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization Bhutan’s story of controlling iodine deficiency. 2003. Available from: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/2260611/Bhutan's-Story-of-Controlling-Iodine-Deficiency. Accessed June 12, 2011.

- 28.Ahmad K. The end of tobacco sales in Bhutan. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(2):69. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(05)01721-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobgay T, Torres CE, Na-Bangchang K. Malaria prevention and control in Bhutan: successes and challenges. Acta Trop. 2011;117(3):225–228. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Bank Bhutan country overview. 2009. Available from: http://www.web.worldbank.org/wbsite/external/countries/southasiaext/bhutanextn/0,,contentMDK:20196794~pagePK:141137~piPK:141127~theSitePK:306149,00.html. Accessed October 10, 2009.

- 31.Planning Commission Bhutan millenium development goals: need assessment and costing report (2006–2015) 2007. Available from: http://www.undp.org.bt/assets/files/Environment/PE%20Mainstreaming%20Pro%20Doc.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2011.

- 32.World Health Organization SEARO notes and news. Regional Health Forum. 1997. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/Regional_Health_Forum_c12.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2010.

- 33.Ministry of Health General synopsis and history. 2009. Available from: http://www.health.gov.bt/healthOverview.php. Accessed September 19, 2010.

- 34.Gross National Happiness Commission . Thimphu: GNH Commission; 2009. Tenth Five year Plan (2008–2013): Vol II Main document 2. Available from: http://www.gnhc.gov.bt/five-year-plan/. Accessed November 10, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enemark U, Melgaard B, Sonderstrup E. Bhutan: Health Sector Review. 2007. (unpublished report). Thimphu, Bhutan: Ministry of Health.

- 36.Zangmo T. Gross National Happiness indicator survey – psychological wellbeing report. 2008. Available from: http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/surveyReports/psychological/psycho_abs.aspx?d=pw&t=Psychological%20Wellbeing. Accessed June 12, 2010.

- 37.Wangdi K. Gross National Happiness indicator survey: health survey report. 2008. Available from: http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/surveyReports/health/health_abs.aspx?d=h&t=Health. Accessed January 25, 2010.

- 38.Rapten P. Gross National Happiness indicator survey: good governance report. 2008. Available from: http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/surveyReports/goodGovernance/goodGovernance_abs.aspx?d=gg&t=Good%20Governance. Accessed January 10, 2010.

- 39.Wangchuk P. Health impacts of traditional medicines and bio-prospecting: a world scenario accentuating Bhutan’s perspective. Journal of Bhutan Studies. 2008;18:117–134. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Tella R, MacCulloch R. Gross National Happiness as an answer to the Easterlin Paradox? Social Science Research Network. 2005. Available from: http://ssrn.com/abstract=707405. Accessed June 14, 2011.

- 41.World Bank Data and statistics 2009. Available from: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/DATASTATISTICS/0,,contentMDK:20421402~pagePK:64133150~piPK:64133175~theSitePK:239419,00.html#South_Asia. Accessed October 10, 2009.

- 42.National Statistical Bureau . Bhutan: poverty analysis report 2007. Available from: http://www.nsb.gov.bt/index.jsp. Accessed December 7, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorji C. Achieving Gross National Happiness through Community-bases Mental Health Services in Bhutan. Available from: http://www.bhutanstudies.org.bt/pubFiles/20.GNH4.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2009.

- 44.Dorji T. Effect of TRIPS on pricing, affordability and access to essential medicines in Bhutan. Journal of Bhutan Studies. 2007;16:128–141. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ministry of Health Bhutan Health Trust Fund. 2009. Available from: http://www.health.gov.bt/bhtf/index.htm. Accessed October 10, 2010.

- 46.Von Schirnding Y, Mulholland C. Health in the Context of Sustainable Development: An Introductory Document. Oslo: World Health Organization; 2002. Available from: http://www.bvsde.paho.org/bvsacd/ssataller/heasustdev.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2011. [Google Scholar]