Abstract

Nurse practitioners (NPs) have a unique opportunity as frontline caregivers and patient educators to recognize, assess, and effectively treat the widespread problem of uncontrolled asthma. This review provides a perspective on the role of the NP in implementing the revised National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) Guidelines put forth by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, thereby helping patients achieve and maintain asthma control. A literature search of PubMed was performed using the terms asthma, nurse practitioner, asthma control, burden, impact, morbidity, mortality, productivity, quality of life, uncontrolled asthma, NAEPP guidelines, assessment, pharmacotherapy, safety. Despite the increased morbidity and mortality and impaired quality of life attributable to uncontrolled asthma, the 2007 NAEPP asthma guidelines are greatly underused. NPs have an opportunity to identify patients at risk and provide enhanced care and education for asthma control. Often, NPs can prescribe medication for and manage these patients, but it is necessary to be able to discern which patients require referral to a specialist.

Keywords: asthma control, asthma medications, education, NAEPP guidelines, nurse practitioner, referral

Introduction

Asthma is a global health problem, burdening patients, families, health care systems, and governments.1 Despite the availability of several treatments and disease management guidelines, many patients have asthma that remains uncontrolled or not adequately controlled.2,3 In a study by Sullivan et al, few patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma achieved asthma control during a 2-year period: 83% of patients had uncontrolled asthma, 16% had asthma inconsistently controlled, and only 1.3% had controlled asthma during all assessment periods.4

The review

This article is intended to increase nurse practitioners’ (NPs) awareness of the prevalence of uncontrolled asthma and provide key information and tools for assessing and maintaining asthma control.

Source materials

The 2007 National Asthma Education Prevention Plan (NAEPP) guideline recommendations for asthma assessment and management, including referral of patients with difficult-to-treat asthma to an asthma specialist, serve as the primary source material. In addition, selected references related to asthma epidemiology and pathophysiology were obtained from a literature search of PubMed using the terms: asthma, nurse practitioner, asthma control, burden, impact, morbidity, mortality, productivity, quality of life, uncontrolled asthma, NAEPP guidelines, assessment, pharmacotherapy, safety.

Benefits of controlled asthma

Uncontrolled asthma can lead to increased morbidity and mortality, impaired quality of life (QOL), and increased absenteeism from work and school.5 Increased health care costs including both direct and indirect costs of asthma management are another consequence of uncontrolled asthma,5 thus underscoring the need for improved symptom control among people with asthma.

Controlled asthma has been shown to reduce morbidity, improve QOL, increase productivity, and improve health outcomes.4,6 In addition, data from the 2006 US National Health and Wellness Survey showed that patients with controlled asthma reported decreased medical resource utilization (fewer emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and unscheduled clinic visits) compared with patients who had uncontrolled asthma.6 The improved health outcomes associated with asthma control indicate that management with therapies that optimize asthma control may reduce direct and indirect costs of treatment.4

2007 NAEPP asthma guidelines (EPR-3) for asthma control

In 2007, the NAEPP issued the third Expert Panel Report (EPR-3), a set of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines that incorporate best practices to help people with asthma control their disease, and provide guidance to clinicians in asthma management.7 Major changes from the previous set of guidelines include a new focus on monitoring asthma control as the goal for asthma therapy and on distinguishing between classifying asthma severity (defined as the intensity of the disease process) and monitoring asthma control (defined as the degree to which therapeutic interventions minimize the manifestations of asthma or meet the goals of therapy).7 These guidelines emphasize that the functions of assessment and monitoring are closely linked to the concepts of severity, control, and the patient’s responsiveness to treatment, and that both severity and control include the domains of current impairment and future risk.7 Impairment is described as the frequency and intensity of symptoms or functional limitations the patient encounters, and risk is defined as the possibility of asthma exacerbations, progressive decline in lung function (or, for children, lung growth), or adverse effects related to asthma medications.7 Including the domains of current impairment and future risk reflects the multifaceted nature of asthma, and the need to consider separately the impact of asthma QOL, functional capacity, and the risk of future adverse events (AEs).7

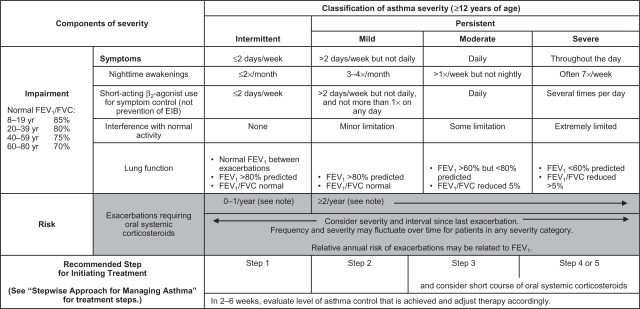

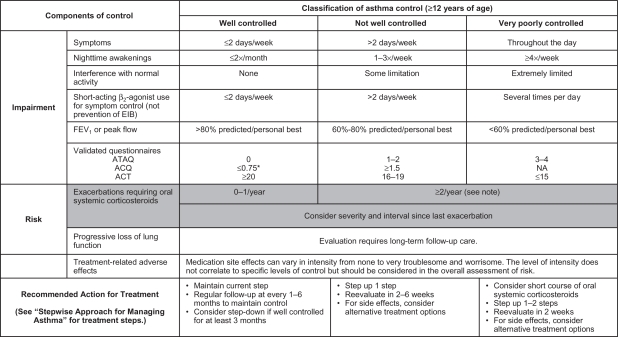

The EPR-3 provides specific guidance for periodic assessment and ongoing monitoring to determine whether the goals of asthma therapy are being achieved and asthma is being controlled.7 Figure 1 shows the recommended methods for classifying asthma severity; Figure 2 shows the recommended methods for classifying asthma control. Asthma severity should be assessed to provide a basis for initial treatment; once treatment is initiated, the focus of clinical management becomes the assessment of asthma control to determine whether therapy should be maintained or adjusted. Periodic assessment of asthma control is recommended at 1- to 6-month intervals and should include measuring signs and symptoms of asthma, pulmonary function, history of asthma exacerbations, and aspects of pharmacotherapy.7 The level of asthma control is the degree to which both domains of the manifestations of asthma – impairment and risk – are minimized by therapeutic intervention.7 The current guidelines classify levels of asthma control using the following categories: well controlled, not well controlled, or very poorly controlled.7

Figure 1.

Methods of classifying asthma severity and initiating treatment in patients 12 years of age and older.

Notes: Level of severity is determined by assessment of both impairment and risk. Assess impairment domain by patient’s/caregiver’s recall of previous 2–4 weeks and spirometry. Assign severity to the most severe category in which any feature occurs. At present, there are inadequate data to correspond frequencies of exacerbations with different levels of asthma severity. In general, more frequent and intense exacerbations (eg, requiring urgent, unscheduled care, hospitalization, or ICU admission) indicate greater underlying disease severity. For treatment purposes, patients who had ≥2 exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have persistent asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with persistent asthma. Reproduced from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.7

Abbreviations: EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Methods of classifying asthma control and adjusting treatment in patients 12 years of age and older.

Notes: *ACQ values of 0.76 to 1.4 are indeterminate for well-controlled asthma. Minimal Important Difference: 1.0 for the ATAQ; 0.5 for the ACQ; not determined for the ACT. The level of control is based on the most severe impairment or risk category. Assess impairment domain by patient’s recall of previous 2–4 weeks and by spirometry or peak flow measures. Symptom assessment for longer periods should reflect a global assessment, such as inquiring whether the patient’s asthma is better or worse since the last visit. At present, there are inadequate data to correspond frequencies of exacerbations with different levels of asthma control. In general, more frequent and intense exacerbations (eg, requiring urgent, unscheduled care, hospitalization, or ICU admission) indicate poorer disease control. For treatment purposes, patients who had ≥2 exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have not-well-controlled asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with not-well-controlled asthma. Before step-up in therapy: (1) Review adherence to medication, inhaler technique, environmental control, and comorbid conditions. (2) If an alternative treatment option was used in a step, discontinue and use the preferred treatment for that step. Reproduced from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.7

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; EIB, exercise-induced bronchospasm; N/A, not applicable; ATAQ, Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire; ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; ACT, Asthma Control Test.

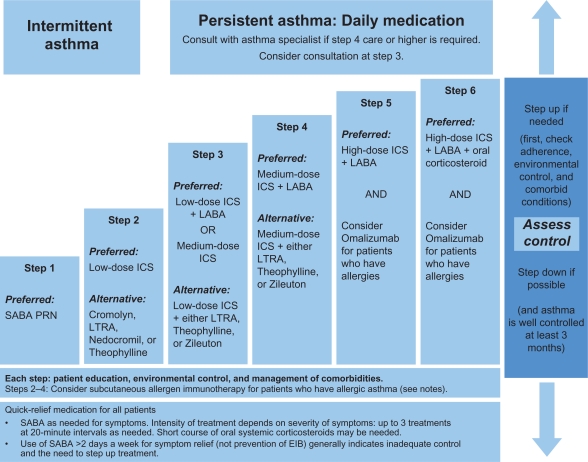

To achieve and maintain control of asthma, the guidelines recommend a stepwise approach that utilizes 6 steps.7 This approach is outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Stepwise approach for managing asthma in patients aged ≥12 years.

Note: Alphabetical order is used when more than one treatment option is listed within either preferred or alternative therapy. Reproduced from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.7

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting inhaled beta2-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; SABA, inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist.

The importance of adhering to guidelines in order to meet and maintain goals of asthma control was demonstrated in a large, randomized, double-blind, intervention trial in which significant reductions in the rate of severe exacerbations and improvements in QOL resulted when asthma control as defined by the Global Initiative for Asthma/National Institutes of Health (NIH) was achieved.8

Results from an intervention-based asthma assessment and management program suggested that implementing asthma guidelines at the point of care may lead to improved asthma control.9 Nevertheless, there are known gaps between the development and distribution of guidelines and their implementation; in fact, it often takes many years for guidelines to be incorporated into clinical practice.10 The NAEPP treatment guidelines have had limited effects on physician behavior, thus contributing to their underutilization in practice.11 Possible barriers to guideline use include patient- and environmental-related factors such as patient resistance to guidelines or the need for additional office and counseling resources. In addition, if guidelines are inconvenient, cumbersome, or confusing, they may not be incorporated into clinical practice.12–15

The advantages of NPs as educators and primary providers

NPs have a unique opportunity to identify patients at risk, and provide enhanced care and education for asthma control, because they are at the front line of patient care.16 Both prospective and “real-world” observational studies have shown that NPs are key primary providers and educators in the management of chronic diseases, including asthma, acting as partners with physicians in providing complementary, collaborative, chronic disease management associated with favorable patient outcomes.17,18 A cross-sectional survey showed that nearly 50% of patients preferred NPs to general practitioners (or had no preference) for educational aspects of care, and were more satisfied with the NP for those aspects of care related to support of patients and their families.19 Conversely, patients preferred medical aspects of care to be managed by the physician.19 A qualitative interview study showed that the input of specialist nurses helped practice nurses to identify, follow-up, and audit the care of high-risk asthma patients.20 In the inpatient setting, pediatric NPs have been shown to be effective care managers and educators.21 These findings underscore the beneficial skill mix provided when NPs and physicians work together for their patients, showing that this approach may meet the needs of patients more effectively than care from the physician alone.

A sound partnership between the NP and patient is critical for consistent asthma control.7 The NP can develop an active partnership with the patient by establishing open communication; identifying and addressing patient and family concerns about asthma and asthma treatment; developing treatment goals; selecting medications collaboratively with the physician, patient, and family; and encouraging self-monitoring and treatment.7 Self-management education, in particular, has been shown to improve outcomes (eg, reduced the number of emergency department visits, hospitalizations, limitations on activities, improved health status, QOL, and perceived control of asthma).7 A hospital-based study showed that asthma consultations with specialist asthma nurses improved patient self-management behavior and thereby reduced symptoms, improved lung function, and decreased work days lost.22

Assessment of asthma control

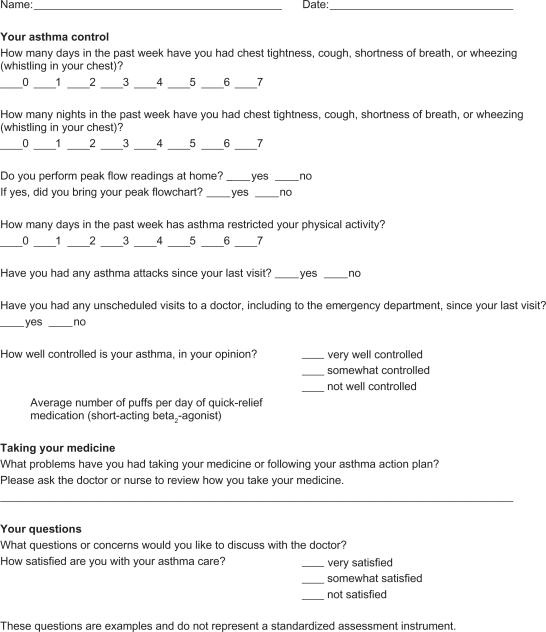

A key role of the NP is evaluating the patient’s asthma control. This ongoing process involves both clinical and patient self-assessment (see Figure 4 for a sample patient’s assessment sheet). The primary methods for clinical monitoring and control of asthma in clinical practice are assessment of symptoms; use of short-acting β2-agonists for quick relief of symptoms; and limitations on normal activities due to asthma, pulmonary function, and exacerbations.7 In addition, the EPR-3 recommends that patients be encouraged to use self-assessment tools.7 Obtaining the perspective of the patient and/or the patient’s family on whether the patient’s asthma is well controlled can add to the clinical evaluation. The “rule of 2s”, which classifies asthma control based on frequency of asthma symptoms, nighttime awakenings, and use of short-acting beta2 agonists (SABAs) for symptom control, is a helpful interpretation of the patient’s input. These and other components of asthma control are described in Table 1.7

Figure 4.

Sample patient self-assessment sheet for follow-up visits.

Table 1.

Classification of well-controlled asthma

| Components of control | Value |

|---|---|

| The “Rule of 2s” | |

| Asthma symptoms | ≤2 days per week |

| Nighttime awakenings | ≤2 times per month |

| SABA use for symptom control (not prevention of EIB) | ≤2 days per week |

| Other measurements | |

| Interference with normal activity | None |

| FEV1 or PEF | >80% predicted/personal best |

Abbreviations: EIB, exercise-induced bronchoconstriction; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; PEF, peak expiratory flow; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist

Note: Reproduced from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.7

Assessing asthma control can help the NP evaluate both current health status and identify patients at risk for future health impairment.23 Some of the validated instruments available for assessing asthma control include the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), the Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ), and the Asthma Control Test (ACT) (Table 2).7 An official statement by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society acknowledged that these tools are easy to administer and interpret but do not provide full information on a patient’s current clinical state and should only be used as a part of a full assessment.24

Table 2.

| Instrument | Assessments | Number of questions/items | Score interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma control questionnaire (ACQ)25,26 |

|

7 | 0 = totally controlled 6 = severely uncontrolled |

| Asthma therapy assessment questionnaire (ATAQ)27 |

|

4 | 0 = no control issues 4 = 4 control issues |

| Asthma control test (ACT)29 |

|

5 | Not specified – up to discretion of physician |

ACQ

The ACQ is a questionnaire developed to meet the criteria set forth by international guidelines (ie, those issued by the Global Initiative for Asthma and the British Thoracic Society) for optimizing asthma control.25 This tool measures the adequacy of and change in asthma control (spontaneous or as a result of treatment).26 Consisting of 7 equally weighted items, the ACQ scores the patient-reported frequency of nighttime awakenings, symptoms on waking, activity limitation, shortness of breath, wheeze, rescue SABA use during the prior week, and clinic-evaluation forced expiratory volume in 1 second % predicted prebronchodilator.25 The total ACQ score is the mean of the 7 items, which ranges from 0 (totally controlled) to 6 (severely uncontrolled).25

ATAQ

The ATAQ is a self-administered questionnaire that assesses asthma control with questions about self-perceived asthma symptom control; missed work, school, or daily activities; nighttime awakenings due to symptoms; and use of quick-relief inhaler medication.27 The number of control problems is summed from all questions for a total score in which 0 = no control issues present and 4 = all 4 control issues present.27 This index provides a simple way to identify patients potentially at risk of poor asthma control, and can detect specific problem areas (eg, overuse of reliever medications, nocturnal wakening, and interference with activities) that can serve as a basis for discussion with the patient.28

ACT

The ACT is a 5-item questionnaire, administered in the doctor’s office, which evaluates patient-reported shortness of breath, asthma control, use of rescue medication, productivity at work or school, and nighttime awakenings due to asthma symptoms.29 Although ACT could be used for many different applications (eg, an investigator selecting patients for clinical trials or a clinician involved in a disease management program), it does not provide a particular score level as a cut point; rather, the designers of this instrument encourage health care providers to select the most appropriate cut point for their patient’s situation.29 The combination of the ACT and lung function testing has been shown to be a more useful strategy for predicting future exacerbation of asthma compared with either method used alone.30

The asthma action plan

An asthma action plan – a written, individualized set of instructions for daily management (including actions to manage worsening asthma and signs and symptoms that indicate the need for immediate medical care) – is a tool NPs can use to help optimize a patient’s asthma control. The NAEPP recommends that all asthma patients be provided with such a plan.7 The use of an action plan as part of the patient’s asthma self-management has been shown to reduce the number of missed school and work days, unscheduled clinic visits, ED visits, and hospitalizations.31 With the use of an asthma action plan, patients are empowered to prevent their symptoms from getting worse, monitor symptoms or peak expiratory flows to guide an appropriate response, and take their prescribed controller and rescue medications. It is important to note that studies have shown that reviewing a patient’s asthma action plan at every visit can increase the patient’s medication adherence.32 Patients should bring their asthma action plans to every scheduled and unscheduled asthma-related visit. This will enhance continuity of care.

Five effective elements of asthma action plans include: (1) recommended doses and schedule of daily medications and how to adjust them in response to particular symptoms or peak flow measurements; (2) a record of the patient’s “best” peak flow measurement, as well as ranges of impairment, which can help patients recognize when control is being compromised; (3) warning signs and symptoms that indicate the need for closer monitoring or acute care; (4) emergency telephone numbers for the health care provider, ED, rapid transportation, and family or friends; and (5) list of triggers that may cause an asthma attack to inform the patient and others of triggers to avoid.

Anticipating and answering patients’ questions

As part of overall asthma management, NPs are well prepared to provide the education necessary to improve symptom control.16 The role of education extends to anticipating and answering patients’ questions about their degree of asthma control. The patient may want and need to address issues that can be resolved with information or a change in therapy. If the patient asks why his or her asthma is not controlled, the NP should explore possible reasons and ensure that patients know their asthma triggers and avoid environmental exposures that worsen their asthma, such as allergens, irritants, and tobacco smoke.7 It is equally important to ensure that the patient is taking medication as prescribed. This includes the correct use of devices such as inhalers, spacers, and nebulizers, which should be demonstrated to the patient by the NP and then demonstrated by the patient to the NP.7 The patient should not be blamed if he or she is not taking medication as prescribed; rather, he or she should be made aware that many patients with asthma and other chronic diseases are nonadherent to therapy but that adherence is extremely important for successful outcomes.33,34

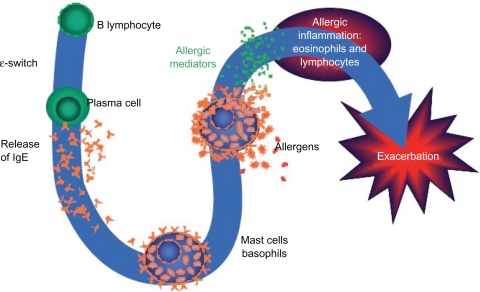

Patients who are practicing trigger avoidance and are taking their medications as prescribed, yet still have uncontrolled asthma, may require a change in treatment. For example, patients with allergic asthma, who comprise more than half of individuals with asthma, may need a medication that addresses the allergic component of the disease.35 If this is the case, these patients should be educated about the nature of their allergic triggers (Figure 5) and informed about avoidance measures and medications available for treatment.

Figure 5.

Overview of the allergic cascade. IgE (immunoglobulin E) is produced by the plasma cells, which are derived from B lymphocytes. The IgE moves through the extracellular fluid and vasculature until it binds to a high-affinity receptor, primarily found on mast cells and basophils. Cross-linking of the membrane IgE results in degranulation of the cell with mediator release and the resultant symptoms of asthma.

Ledford DK. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:933–943. Copyright © 2009. Informa Healthcare. Reproduced with permission of Informa Healthcare.49

Pharmacotherapy

Classes of asthma medications

NPs have many medication options available when treating their asthma patients. Medications for asthma consist of agents for long-term control and quick-relief rescue.7 Table 3 provides an overview of these medications and their mechanisms of action. Long-term control agents are used daily to achieve and maintain asthma control. The most effective agents in this class counteract the inflammation that underlies asthma.7 This class includes inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs), the cornerstone of treatment for persistent asthma.7,36 In contrast, quick-relief medications (the preferred among which are SABAs) treat acute symptoms, and help prevent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, and exacerbations.7 The anticholinergic agent ipratropium bromide and oral systemic corticosteroids are used in addition to SABAs for the rescue treatment of moderate to severe exacerbations.7 Unlike SABAs, long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs) have a duration of bronchodilatory action of at least 12 hours and are used as controller agents in combination with ICSs (see safety discussion below).7,32,37,38

Table 3.

| How used | Class | Example(s) of approved agents | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term controllers | ICSs | beclomethasone | Anti-inflammatory effects |

| budesonide | |||

| fluticasone | |||

| mometasone | |||

| Immunomodulators | omalizumab | Anti-inflammatory effects | |

| Leukotriene modifiers | montelukast | Anti-inflammatory effects | |

| zileuton | |||

| LABAs | salmeterol | Bronchodilation | |

| formoterol | |||

| Methylxanthines | theophylline | Mild/moderate bronchodilation | |

| Mild anti-inflammatory effects | |||

| Combined ICS/LABA | fluticasone/salmeterol | Anti-inflammatory effects | |

| budesonide/formoterol | Bronchodilation | ||

| Quick-relief/exacerbations | Anticholinergics | ipratropium bromide | Bronchodilation |

| SABAs | albuterol | Bronchodilation | |

| levalbuterol | |||

| Oral corticosteroids | prednisone/prednisolone | Anti-inflammatory effects |

Abbreviations: ICSs, inhaled corticosteroids; LABAs, long-acting β2-agonists; SABAs, short-acting β2-agonists.

Leukotrienes are the key proinflammatory mediators in asthma and the most powerful bronchoconstrictors found in humans to date.39 Leukotriene modifiers consist of 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors (zileuton), which block cysteinyl leukotriene production, and leukotriene receptor antagonists (montelukast and zafirlukast), which block cysteinyl leukotrienes from binding to their primary receptor.7,40 Leukotriene receptor antagonist agents are alternative but not preferred therapy for the treatment of mild persistent asthma.7

The immunomodulator class currently consists solely of omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits binding of immunoglobulin E (IgE) to its receptor on the surface of mast cells and basophils, thereby decreasing mediators of asthmatic inflammation and the allergic response.7,36 Omalizumab is indicated for adolescents and adults with moderate to severe persistent asthma inadequately controlled with ICS who have documented reactivity to a perennial aeroallergen.41 Omalizumab significantly reduced exacerbations in 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trials, each consisting of a 16-week stable steroid phase and a 12-week steroid reduction phase.42,43 Fewer patients with asthma exacerbations were observed with omalizumab versus placebo in the stable steroid phase of these 2 trials (14.6% vs 23.3% and 12.8% vs 30.5%, respectively) as well as the steroid-reduction phase (21.3% vs 32.3% and 15.7% vs 29.8%, respectively).42,43 In a separate study by Holgate et al,44 exacerbation rates in patients treated with omalizumab were 35%–45% lower than the rates observed in the patients treated with placebo, although these differences did not reach statistical significance.44

Safety concerns

Inhaled corticosteroids

The NAEPP guidelines state that ICSs are generally well tolerated and safe when used at the recommended doses.7 However, long-term use (>1 year) of high doses of ICSs, particularly if given in combination with frequent courses of oral corticosteroids, may be associated with the risk of cataracts or reduced bone mineral density.7

Long-acting β2-agonists

Clinical trial evidence of an increased risk of asthma-related deaths in patients treated with salmeterol, and an increased risk of severe asthma exacerbations leading to hospitalizations and deaths, led to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) determination in February 2010 that a black box warning was warranted on the labeling for all LABAs used in asthma.32,45 The FDA also recommended that these agents be used only for patients whose asthma is inadequately controlled with a long-term asthma control medication such as an ICS, or whose disease severity clearly warrants initiation of treatment with both an ICS and LABA, and that LABAs should be discontinued (but ICSs continued) once asthma control is achieved.7,45 This safety communication also added a contraindication for LABA use without concomitant treatment with an asthma controller medication such as an ICS.45

Omalizumab

An analysis of data from controlled studies with omalizumab showed that the incidence of anaphylaxis (reported by investigator) was rare (omalizumab 0.14%, control 0.07%).46 A separate analysis of the postmarketing safety database, including an estimated exposure of 57,300 patients from June 2003 to December 2006, indicated 124 cases of anaphylaxis attributable to omalizumab (0.2%).47 The labeling for omalizumab includes a warning concerning this risk of anaphylaxis, and recommends that patients be observed closely after drug administration.41 The warning also stipulates that health care providers administering omalizumab be prepared to manage anaphylaxis, and inform patients of the signs and symptoms of the condition so that they can seek immediate medical care should symptoms occur.41

Malignant neoplasms were observed in 0.5% of omalizumab-treated patients compared with 0.2% of control patients in clinical studies of adults and adolescents (aged ≥ 12 years) with asthma and other allergic disorders.46 The majority of malignant neoplasms were reported during the first 52 weeks of treatment and the impact of longer exposure to omalizumab is not known.46 Based on comparisons with the NIH Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, the incidence of malignancy in the omalizumab group was found to be similar to the incidence expected in the general population.46 In a separate analysis, an expert panel of oncologists concluded that the increased occurrence of malignancies observed in clinical trials was not due to omalizumab and that the malignancies occurred before the study began.48 Furthermore, of the 25 reported neoplasms, 22 were found to be unrelated to the study drug and 3 were believed to have a remote relation to it.48

The patient with difficult-to-treat asthma: when to refer to a specialist

Some patients with asthma are beyond the scope of general practice. The NAEPP guidelines recommend referral to a specialist if the patient meets any of the following criteria: asthma is difficult to control or is persistent, the patient has needed more than 2 oral corticosteroid bursts per year, exacerbations have required hospitalization, therapy at step 4 or higher is required to achieve adequate asthma control, immunotherapy or therapy with omalizumab is being considered, or additional testing is needed.7 Table 4 summarizes these criteria.

Table 4.

Criteria for referring a patient with difficult-to-treat asthma to a specialist

Patients should be referred if they meet ANY of the criteria below: below:

|

Note: Reproduced from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.7

Conclusion

Many patients live with uncontrolled asthma, despite the availability of effective treatment options. NPs have a unique opportunity as frontline caregivers and patient educators to recognize and assess uncontrolled asthma as well as determine the steps necessary to help patients gain and maintain symptom control. With the implementation of the NAEPP guidelines, the role of NPs in asthma care will become particularly critical. NPs are ideally suited to the roles of primary purveyors of asthma education, promoters of patient partnerships for health care optimization, and providers of ongoing monitoring to ensure consistent achievement of therapeutic goals for asthma control.16

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Kristin Carlin, RPh, MBA, and Embryon, Inc for writing and editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Funding

This article was funded by Genentech, Inc, South San Francisco, CA, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA.

Disclosure

Dr Rance is a speaker for Merck and Co, Inc.

References

- 1.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, et al. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy. 2004;59:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters SP, Jones CA, Haselkorn T, et al. Real-world Evaluation of Asthma Control and Treatment (REACT): findings from a national Web-based survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1454–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman KR, Boulet LP, Rea RM, et al. Suboptimal asthma control: prevalence, detection and consequences in general practice. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:320–325. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00039707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan SD, Rasouliyan L, Russo PA, et al. Extent, patterns, and burden of uncontrolled disease in severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. Allergy. 2007;62:126–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Lung Association American Lung Association Epidemiology and Statistics Unit Research and Program Services. Trends in asthma morbidity and mortality. 2008:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams SA, Wagner S, Kannan H, et al. The association between asthma control and health care utilization, work productivity loss and health-related quality of life. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:780–785. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181abb019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Expert Panel Report 3: guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma Summary Report 2007. 2007:1–74. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma Control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:836–844. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-033OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlton BG, Lucas DO, Ellis EF, et al. The status of asthma control and asthma prescribing practices in the United States: results of a large prospective asthma control survey of primary care practices. J Asthma. 2005;42:529–535. doi: 10.1081/JAS-67000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lomas J, Anderson GM, Domnick-Pierre K, et al. Do practice guidelines guide practice? The effect of a consensus statement on the practice of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1306–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rastogi D, Shetty A, Neugebauer R, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines and asthma management practices among inner-city pediatric primary care providers. Chest. 2006;129:619–623. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navaratnam P, Jayawant SS, Pedersen CA, et al. Physician adherence to the national asthma prescribing guidelines: evidence from national out-patient survey data in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:216–221. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolf SH. Practice guidelines: a new reality in medicine. III. Impact on patient care. Arch Int Med. 1993;153:2646–2655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabana MD, Ebel BE, Cooper-Patrick L, et al. Barriers pediatricians face when using asthma practice guidelines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:685–693. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.7.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayden ML, Rachelefsky G. Partners for better athma control. Newest guidelines highlight value of NP care. Adv Nurse Pract. 2008;16:45–48. 50–52, 54–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, et al. Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;283:59–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litaker D, Mion L, Planavsky L, et al. Physician – nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: the impact on costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients’ perception of care. J Interprof Care. 2003;17:223–237. doi: 10.1080/1356182031000122852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laurant MG, Hermens RP, Braspenning JC, et al. An overview of patients’ preference for, and satisfaction with, care provided by general practitioners and nurse practitioners. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:2690–2698. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster G, Gantley M, Feder G, et al. How do clinical nurse specialists influence primary care management of asthma? A qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J. 2005;14:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borgmeyer A, Gyr PM, Jamerson PA, et al. Evaluation of the role of the pediatric nurse practitioner in an inpatient asthma program. J Pediatr Health Care. 2008;22:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy ML, Robb M, Allen J, et al. A randomized controlled evaluation of specialist nurse education following accident and emergency department attendance for acute asthma. Respir Med. 2000;94:900–908. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H, Gould MK, Blanc PD, et al. Asthma control, severity, and quality of life: quantifying the effect of uncontrolled disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:59–99. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juniper EF, Bousquet J, Abetz L, et al. Identifying ‘well-controlled’ and ‘not well-controlled’ asthma using the Asthma Control Questionnaire. Respir Med. 2006;100:616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juniper EF, O’Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:902–907. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vollmer WM, Markson LE, O’Connor E, et al. Association of asthma control with health care utilization and quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1647–1652. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9902098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vollmer WM. Assessment of asthma control and severity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:409–413. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato R, Tomita K, Sano H, et al. The strategy for predicting future exacerbation of asthma using a combination of the Asthma Control Test and lung function test. J Asthma. 2009;46:677–682. doi: 10.1080/02770900902972160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J, et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001117. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Expert Panel Report 3: guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma Full Report 2007. 2007 Aug 28;:1–440. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dekker FW, Dieleman FE, Kaptein AA, et al. Compliance with pulmonary medication in general practice. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:886–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Smet BD, Erickson SR, Kirking DM. Self-reported adherence in patients with asthma. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:414–420. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arbes SJ, Jr, Gergen PJ, Vaughn B, et al. Asthma cases attributable to atopy: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1139–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanania NA. Targeting airway inflammation in asthma: current and future therapies. Chest. 2008;133:989–998. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creticos PS. Managing asthma in adults. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:S940–S963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donohue JF. Therapeutic responses in asthma and COPD. Bronchodilators. Chest. 2004;126:125S–137S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2_suppl_1.125S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh RK, Gupta S, Dastidar S, et al. Cysteinyl leukotrienes and their receptors: molecular and functional characteristics. Pharmacology. 2010;85:336–349. doi: 10.1159/000312669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tantisira KG, Lima J, Sylvia J, et al. 5-lipoxygenase pharmacogenetics in asthma: overlap with Cys-leukotriene receptor antagonist loci. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19:244–247. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328326e0b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.US Food and Drug Administration Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. www fda gov. Aug, 2010. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction_Search.Label_ApprovalHistory. Accessed June 26, 2011.

- 42.Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:184–190. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soler M, Matz J, Townley R, et al. The anti-IgE antibody omalizumab reduces exacerbations and steroid requirement in allergic asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:254–261. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00092101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holgate ST, Chuchalin AG, Hebert J, et al. Efficacy and safety of a recombinant anti-immunoglobulin E antibody (omalizumab) in severe allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:632–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Food and Drug Administration FDA Drug Safety Communication: new safety requirements for long-acting inhaled asthma medications called Long-Acting Beta-Agonists (LABAs) Feb 18, 2010.

- 46.Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Limb SL, Starke PR, Lee CE, et al. Delayed onset and protracted progression of anaphylaxis after omalizumab administration in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1378–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuhn R. Immunoglobulin E blockade in the treatment of asthma. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1412–1424. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.10.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ledford DK. Omalizumab: overview of pharmacology and efficacy in asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:933–943. doi: 10.1517/14712590903036060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]