Abstract

Background: It is not clear why cardiac or renal cachexia in chronic diseases is associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes. Platelet reactivity predisposes to thromboembolic events in the setting of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, which is often present in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Objectives: We hypothesized that ESRD patients with relative thrombocytosis (platelet count >300 × 103/μL) have a higher mortality rate and that this association may be related to malnutrition-inflammation cachexia syndrome (MICS).

Design: We examined the associations of 3-mo-averaged platelet counts with markers of MICS and 6-y all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (2001–2007) in a cohort of 40,797 patients who were receiving maintenance hemodialysis.

Results: The patients comprised 46% women and 34% African Americans, and 46% of the patients had diabetes. The 3-mo-averaged platelet count was 229 ± 78 × 103/μL. In unadjusted and case-mix adjusted models, lower values of albumin, creatinine, protein intake, hemoglobin, and dialysis dose and a higher erythropoietin dose were associated with a higher platelet count. Compared with patients with a platelet count of between 150 and 200 × 103/μL (reference), the all-cause (and cardiovascular) mortality rate with platelet counts between 300 and <350, between 350 and <400, and ≥400 ×103/μL were 6% (and 7%), 17% (and 15%), and 24% (and 25%) higher (P < 0.05), respectively. The associations persisted after control for case-mix adjustment, but adjustment for MICS abolished them.

Conclusions: Relative thrombocytosis is associated with a worse MICS profile, a lower dialysis dose, and higher all-cause and cardiovascular disease death risk in hemodialysis patients; and its all-cause and cardiovascular mortality predictability is accounted for by MICS. The role of platelet activation in cachexia-associated mortality warrants additional studies.

INTRODUCTION

Cachexia is a common condition among 5 million Americans with CHF6 and half a million Americans with ESRD requiring maintenance dialysis treatment to survive (1, 2). Cardiovascular mortality accounts for most deaths in ESRD and CHF patients (3). Whereas a decline in cardiovascular deaths has occurred in the general population, a similar trend has not been observed in CHF or dialysis patients (3, 4).

Platelet reactivity plays a central role in the genesis of thrombosis and thromboembolic events, especially in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease—the leading cause of death in ESRD and CHF patients (3). To this end, antiplatelet therapy is used to decrease the occurrence of thromboembolic events (5). Even relative thrombocytosis (ie, platelet counts >300 × 103/μL) can be associated with the severity of cardiovascular disease in ESRD patient populations (6). High ex vivo platelet reactivity appears to be associated with ischemic events (7).

Renal cachexia, also known as PEW, is common in ESRD patients and is associated with poor outcomes (8, 9). The close link between inflammation and PEW has led to the designation “malnutrition-inflammation-cachexia syndrome” (10). MICS is a strong predictor of cardiovascular mortality in ESRD patients (8, 11). However, even though many dialysis patients have preexisting cardiovascular disease and poor survival, it is still not clear why PEW, which is not a cardiovascular disease risk factor per se, is associated with higher cardiovascular mortality in this patient population. Discovering the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying the PEW-death link can be a major step toward improving the clinical management of chronic diseases states with wasting syndrome.

In the general population, differences in platelet counts exist between men and women and between different ethnic groups (12). Inflammatory cytokines are potent thrombopoietic factors (13), and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-11 enhance megakaryocyte maturation (14). Cachexia, which is a proinflammatory condition per se, might lead to thrombocytosis and predispose to thromboembolic events and death, especially in the setting of preexisting cardiovascular disease. To date, no study has assessed the complex association between platelet count, MICS, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

With the use of a large and contemporary cohort of maintenance hemodialysis patients from a single dialysis provider, we examined the hypothesis that a higher platelet count is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality and that renal cachexia plays a role in this association.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Patients

We extracted, refined, and examined data from all individuals with ESRD who underwent hemodialysis treatment from July 2001 through June 2007 in 1 of 580 outpatient dialysis facilities of DaVita (DaVita Inc, before its acquisition of former Gambro dialysis facilities). The study was approved by all relevant Institutional Review Committees. Because of the large sample size, the anonymity of the patients studied, and the nonintrusive nature of the research, the study was exempt from the requirement of written consent. The first (baseline) studied quarter for each patient was the calendar quarter in which the patient's vintage was >90 d. We studied those hemodialysis patients whose platelet counts were measured, whose ages were between 16 and 99 y, who had started hemodialysis treatment in DaVita within the first 3 mo of therapy, and had a BMI (in kg/m2) between 12 and 60.

Clinical and demographic measures

The creation of the national DaVita maintenance hemodialysis patient cohort was described previously (15–19). To minimize measurement variability, all repeated measures for each patient during any given calendar quarter, ie, over a 13-wk interval, were averaged, and the summary estimates were used in all models. Dialysis vintage was defined as the duration of time between the first day of dialysis treatment and the first day that the patient entered the cohort. The presence or absence of diabetes at baseline and race-ethnicity were obtained directly from the DaVita database. Histories of tobacco smoking and preexisting comorbid conditions were obtained by linking the DaVita database to the Medical Evidence Form 2728 of the US Renal Data System (20).

Cardiovascular death

The recorded causes of death were obtained from the US Renal Data System, and cardiovascular death was defined as death due to myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, and other cardiac causes.

Laboratory measures

Blood samples were drawn by using uniform techniques in all dialysis clinics and were transported to the DaVita Laboratory in Deland, FL, within 24 h. All laboratory values were measured by automated and standardized methods. Most laboratory values were measured monthly. Hemoglobin was measured at least monthly in all patients and weekly to biweekly in most patients. Glycated hemoglobin was usually measured semiannually or quarterly. The normalized protein equivalent of total nitrogen appearance (nPNA), also known as normalized protein catabolic rate (nPCR), was measured monthly as a measure of daily protein intake. Most blood samples were collected predialysis, except for postdialysis serum urea nitrogen to calculate urea kinetics. Platelet count was measured monthly as a part of the complete blood count. To create commensurate baseline values across diverse laboratory measures and to mitigate the measurement error, we averaged all weekly to monthly values into one single quarterly value per patient. Hence, the baseline platelet count used in this study was the averages of up to 3 monthly values per patient during the base calendar quarter. We divided platelet number into 7 a priori selected categories and defined the following ranges: <150, 150 to <200, 200 to <250, 250 to <300, 300 to <350, 350 to <400, and ≥400 × 103/μL. For dichotomized analyses, we divided the platelet count into a moderate and a high range, ie, 150 to <300 × 103/μL as the reference and ≥300 × 103/μL as relative thrombocytosis, respectively.

Epidemiologic and statistical methods

The descriptive statistics used include proportions and means (± SD) as appropriate. We used ANOVA to compare patients with different platelet categories. Linear regression models were used to analyze the association between platelet number and different components of MICS. We built univariate and case-mix adjusted models (see below).

Survival analyses, including Cox proportional hazard regressions with baseline measures, were examined to determine whether the 6-y survival rates were associated with platelet counts. We also tested the linearity of all survival models using fractional polynomials and restricted cubic splines. For each analysis, 3 models were examined based on the level of multivariate adjustment:

1) Unadjusted model: included entry calendar quarter (quarter 1 through quarter 20)

2) Case-mix adjusted model: included the above factor plus age, sex, 10 preexisting comorbid states (ischemic heart disease, CHF, status after cardiac arrest, status after myocardial infarction, pericarditis, cardiac dysrhythmia, cerebrovascular events, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer), categories of dialysis vintage (<6 mo, 6 mo to 2 y, 2–5 y, and ≥5 y), primary insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, private, and others), marital status (married, single, divorced, widowed, and other or unknown), the standardized mortality ratio of the dialysis clinic during entry quarter, dialysis dose as indicated by Kt/V (single pool), presence or absence of a dialysis catheter, and residual renal function during the entry quarter (ie, urinary urea clearance).

3) The MICS-adjusted models, which included all of the covariates in the case-mix model as well as 13 surrogates of nutritional status and inflammation, including BMI, the average dose of ESA, and 11 laboratory variables as surrogates of the nutritional state or inflammation, together also known as MICS, with known association with clinical outcomes in hemodialysis patients (21–23): 1) nPNA (nPCR) as an indicator of daily protein intake, 2) serum albumin, 3) serum TIBC, 4) serum ferritin, 5) serum creatinine, 6) serum phosphorus, 7) serum calcium, 8) serum bicarbonate, 9) peripheral white blood cell count, 10) lymphocyte percentage, and 11) iron saturation ratio.

Missing covariate data (<2% for most laboratory and demographic variables and <18% for any of the 10 comorbid conditions) were imputed by the mean or median of the existing values, whichever was most appropriate. All descriptive and multivariate statistics were carried out with SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

The original 6-mo (July to December 2001) national database of all DaVita hemodialysis patients included 47,156 cumulative subjects. After the exclusion of those patients who did not continue hemodialysis treatment for >45 d, 41,093 hemodialysis patients remained for analysis, of whom 306 patients had missing core data, including platelet count or hemoglobin values. The final cohort included 40,787 hemodialysis patients, of whom 33,024 patients originated from the first calendar quarter data set and the rest from the subsequent calendar quarters. These patients were followed until death, loss to follow-up, or survival until 30 June 2007, as recorded in the DaVita databases. Of the 40,787 observed hemodialysis patients with a median follow-up time of 1066 d, there were 27,612 deaths (68%) and 11,051 cardiovascular deaths (27%). The mean age of the patients was 61 ± 15 y, 46% were female, and 46% had diabetes mellitus (Table 1). The 3-mo averaged platelet count was 229 ± 78 × 103/μL. The demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the 40,797 hemodialysis patients in the 6-y DaVita cohort are compared between platelets categories in Table 1. A higher platelet count was associated with a younger age, female sex, and a higher proportion of diabetes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline (first calendar quarter) data for 40,787 hemodialysis patients, including 33,024 patients from the first quarter (July, August, and September 2001), and 7763 patients from the subsequent quarter (October, November, and December 2001)1

| Platelet count |

||||||||

| <150 × 103/μL | 150 to <200 × 103/μL | 200 to <250 × 103/μL | 250 to <300 × 103/μL | 300 to <350 × 103/μL | 350 to <400 × 103/μL | ≥400 × 103/μL | P (ANOVA) | |

| Variable | (n = 4902) | (n = 10,662) | (n = 11,608) | (n = 7330) | (n = 3472) | (n = 1473) | (n = 1250) | |

| Age (y) | 62 ± 152 | 61 ± 15 | 61 ± 15 | 60 ± 15 | 60 ± 15 | 59 ± 15 | 58 ± 15 | <0.001 |

| Sex (% women) | 38 | 42 | 47 | 52 | 53 | 55 | 50 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 40 | 43 | 46 | 49 | 52 | 52 | 50 | <0.001 |

| No. of deaths | 3705 | 7150 | 7546 | 4854 | 2385 | 1050 | 924 | <0.001 |

| Crude death rate (%) | 76 | 67 | 65 | 66 | 69 | 71 | 74 | |

| No. of CVD deaths | 1488 | 2911 | 3016 | 1917 | 960 | 412 | 347 | <0.001 |

| CVD death rate (%) | 30 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 28 | 28 | |

| Race-ethnicity (%) | ||||||||

| White | 41 | 36 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 36 | <0.001 |

| Black | 27 | 32 | 35 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 36 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 16 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 0.016 |

| Other | 16 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 15 | <0.001 |

| Vintage, time on dialysis (%) | ||||||||

| <6 mo | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | <0.001 |

| ≥5 y | 25 | 22 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | <0.001 |

| Primary insurance (%) | ||||||||

| Medicare | 67 | 69 | 68 | 68 | 65 | 65 | 63 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 0.022 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||

| Married | 46 | 43 | 42 | 42 | 39 | 37 | 41 | <0.001 |

| Single | 22 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 26 | <0.001 |

| Kt/V (dialysis dose) | 1.34 ± 0.0.65 | 1.34 ± 0.0.64 | 1.33 ± 0.0.73 | 1.26 ± 0.0.74 | 1.20 ± 0.0.82 | 1.11 ± 0.0.91 | 1.05 ± 0.0.81 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity (%) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Heart failure | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 27 | 0.85 |

| PVD | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 0.024 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 19 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 0.012 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.22 |

| Protein catabolic rate (g · kg−1 · d−1) | 1.00 ± 0.25 | 1.01 ± 0.24 | 1.01 ± 0.24 | 0.99 ± 0.24 | 0.96 ± 0.23 | 0.94 ± 0.23 | 0.93 ± 0.23 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory tests | ||||||||

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.77 ± 0.41 | 3.84 ± 0.35 | 3.82 ± 0.36 | 3.77 ± 0.39 | 3.67 ± 0.40 | 3.57 ± 0.45 | 3.45 ± 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 9.3 ± 3.2 | 9.7 ± 3.3 | 9.6 ± 3.3 | 9.3 ± 3.3 | 9.0 ± 3.2 | 8.6 ± 3.2 | 8.3 ± 2.9 | <0.001 |

| TIBC (mg/dL) | 199 ± 42 | 202 ± 40 | 203 ± 41 | 203 ± 43 | 204 ± 47 | 200 ± 49 | 195 ± 52 | <0.001 |

| Bicarbonate (mg/dL) | 22.1 ± 2.8 | 22.0 ± 2.7 | 22.0 ± 2.7 | 22.0 ± 2.7 | 22.0 ± 2.7 | 22.1 ± 2.8 | 22.1 ± 2.9 | 0.46 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 9.1 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 695 ± 547 | 666 ± 468 | 641 ± 442 | 640 ± 473 | 625 ± 488 | 621 ± 583 | 658 ± 599 | <0.001 |

| Iron saturation ratio | 33 ± 15 | 30 ± 13 | 29 ± 13 | 27 ± 12 | 25 ± 12 | 23 ± 12 | 23 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Blood hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.9 ± 1.3 | 12.0 ± 1.2 | 11.9 ± 1.2 | 11.7 ± 1.2 | 11.4 ± 1.3 | 11.1 ± 1.3 | 10.8 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Platelet count (× 103/μL) | 122 ± 24 | 177 ± 14 | 224 ± 14 | 272 ± 14 | 322 ± 14 | 371 ± 14 | 469 ± 74 | <0.001 |

| WBC (× 103/μL) | 5.9 ± 2.4 | 6.6 ± 1.8 | 7.2 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 2.1 | 8.5 ± 2.5 | 9.2 ± 2.8 | 10.3 ± 3.3 | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte (% of total WBC) | 21 ± 8 | 21 ± 8 | 21 ± 8 | 20 ± 7 | 19 ± 7 | 19 ± 7 | 18 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| ESA dose (units/wk) | 20,740 ± 19,883 | 17,141 ± 15,290 | 17,330 ± 15,469 | 18,753 ± 16,710 | 20,580 ± 17,326 | 22,080 ± 18,149 | 27,514 ± 53,494 | <0.001 |

| Use of any intravenous iron (%) | 59 | 60 | 60 | 62 | 62 | 61 | 59 | <0.001 |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; ESA, erythropoietin stimulating agent; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; TIBC, total-iron-binding content; WBC, white blood cell.

Mean ± SD (all such values).

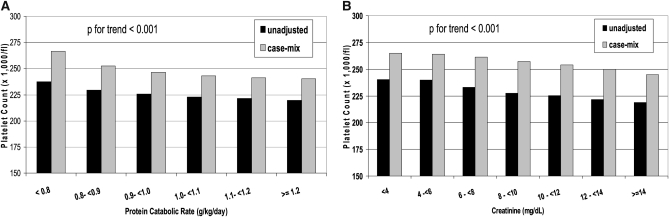

In unadjusted models, both an incrementally higher nPNA (nPCR) (Figure 1, A) and higher serum creatinine concentration (Figure 1B) were associated with a lower platelet count. This association remained significant after adjustment for case-mix (Figure 1). In unadjusted and case-mix adjusted models, incrementally higher blood hemoglobin concentrations were associated with a lower platelet count, whereas incrementally higher ESA doses were associated with a higher platelet count (OSM, Figure 1). Incrementally higher Kt/V values up to 2.2 were associated with a lower platelet count (OSM, Figure 2). A similar trend was found in for the association between serum albumin and platelet count (OSM, Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Association between protein catabolic rate (A) and serum creatinine (B) and predicted platelet count after an unadjusted and case-mix adjusted analysis of linear regression models. Unadjusted model: adjusted for entry calendar quarter (quarter 1 through quarter 20). Case-mix adjusted model: adjusted for entry calendar quarter plus age, sex, 10 preexisting comorbid states, categories of dialysis vintage, primary insurance, marital status, the standardized mortality ratio of the dialysis clinic during entry quarter, dialysis dose as indicated by Kt/V (single pool), the presence or absence of a dialysis catheter, and residual renal function during the entry quarter (ie, urinary urea clearance).

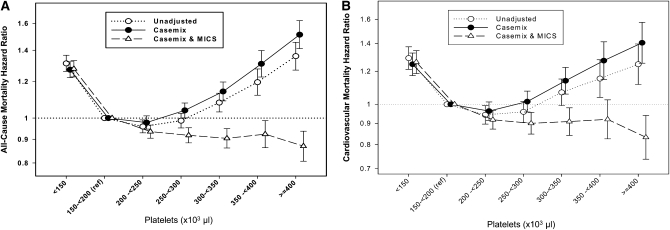

FIGURE 2.

HRs (and 95% CIs) of all-cause mortality (A) and cardiovascular mortality (B) across platelet concentrations after Cox regression analyses in 40,797 long-term hemodialysis patients who were observed over a 6-y observation period (July 2001–June 2007). Unadjusted model: adjusted for entry calendar quarter (quarter 1 through quarter 20). Case-mix adjusted model: adjusted for entry calendar quarter plus age, sex, 10 preexisting comorbid states, categories of dialysis vintage, primary insurance, marital status, the standardized mortality ratio of the dialysis clinic during entry quarter, dialysis dose as indicated by Kt/V (single pool), the presence or absence of a dialysis catheter, and residual renal function during the entry quarter (ie, urinary urea clearance). Case-mix– and malnutrition-inflammation cachexia syndrome (MICS)–adjusted model: adjusted for all of the covariates in the case-mix model plus BMI, the average dose of erythropoietin stimulating agent, normalized protein equivalent of total nitrogen appearance—also known as normalized protein catabolic rate—as an indicator of daily protein intake, serum albumin, serum total-iron-binding capacity, serum ferritin, serum creatinine, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, serum bicarbonate, peripheral white blood cell count, lymphocyte percentage, and iron saturation ratio.

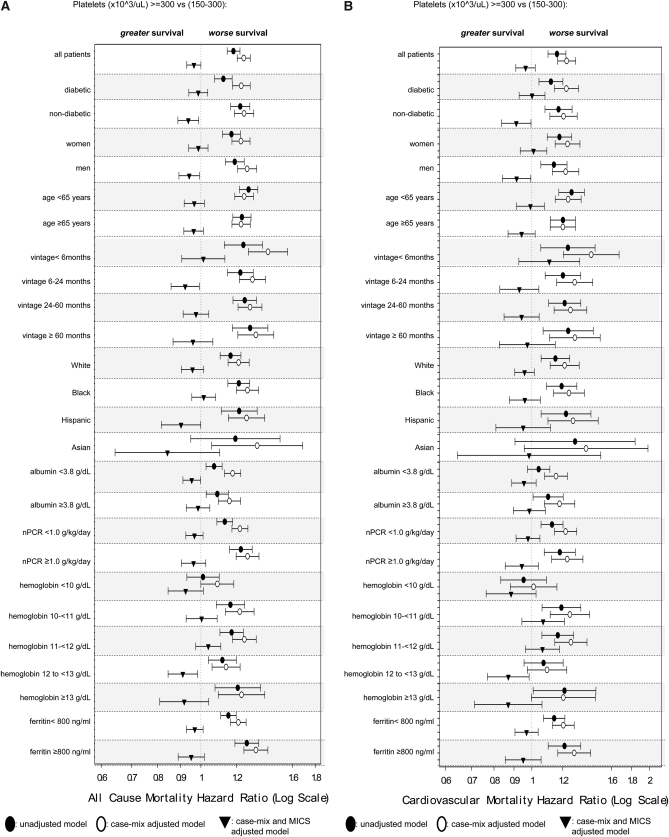

FIGURE 3.

HRs (and 95% CIs) of all-cause mortality (A) and cardiovascular disease mortality (B) between platelet counts [150–300 × 103/μL (reference) compared with ≥300 × 103/μL] by using Cox regression analyses in 40,797 long-term hemodialysis patients who were observed over a 6-y observation period (July 2001–June 2007) in various subgroups of patients. Unadjusted model: adjusted for entry calendar quarter (quarter 1 through quarter 20). Case-mix adjusted model: adjusted for entry calendar quarter plus age, sex, 10 preexisting comorbid states, categories of dialysis vintage, primary insurance, marital status, the standardized mortality ratio of the dialysis clinic during entry quarter, dialysis dose as indicated by Kt/V (single pool), the presence or absence of a dialysis catheter, and residual renal function during the entry quarter (ie, urinary urea clearance). Case-mix– and malnutrition-inflammation cachexia syndrome (MICS)–adjusted model: adjusted for all of the covariates in the case-mix model plus BMI, the average dose of erythropoietin stimulating agent, normalized protein equivalent of total nitrogen appearance—also known as normalized protein catabolic rate (nPCR)—as an indicator of daily protein intake, serum albumin, serum total-iron-binding capacity, serum ferritin, serum creatinine, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, serum bicarbonate, peripheral white blood cell count, lymphocyte percentage, and iron saturation ratio.

To identify the potential risk factors that may link relative thrombocytosis (ie, platelet count ≥300 × 103/μL) to mortality, we performed logistic regression analyses. After case-mix adjustment, the risk of relative thrombocytosis was also associated with younger age, lower serum albumin and creatinine concentrations, lower lymphocyte percentages, and lower Kt/V and nPNA (nPCR) values as a surrogate of lower dietary protein intake (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

ORs (and 95% CIs) for relative thrombocytosis [ie, platelet count ≥300 × 103/μL compared with 150 to <300 × 103/μL (reference)]1

| Unadjusted (n = 40,697) |

Case-mix adjusted2 (n = 40,697) |

|||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (+10-y increase) | 0.93 (0.91, 0.95) | <0.0001 | 0.92 (0.90, 0.94) | <0.0001 |

| Women (compared with men) | 1.32 (1.25, 1.40) | <0.0001 | 1.31 (1.23, 1.39) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetic (compared with nondiabetic) | 1.25 (1.19, 1.33) | <0.0001 | 1.27 (1.20, 1.35) | <0.0001 |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||

| Black (compared with white) | 1.15 (1.08, 1.23) | <0.0001 | 1.07 (0.99, 1.14) | 0.079 |

| Hispanic (compared with white) | 0.95 (0.87, 1.03) | 0.22 | 0.90 (0.82, 0.99) | 0.033 |

| Hispanic (compared with black) | 0.92 (0.75, 0.89) | <0.0001 | 0.81 (0.74, 0.89) | <0.0001 |

| Vintage (+12 mo increase) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.95) | <0.0001 | 0.94 (0.93, 0.95) | <0.0001 |

| Kt/V (+0.1 increase) | 0.86 (0.83, 0.90) | <0.0001 | 0.87 (0.83, 0.91) | <0.0001 |

| Protein catabolic rate (+0.1 g · kg−1 · d−1 increase) | 0.46 (0.41, 0.52) | <0.0001 | 0.51 (0.45, 0.58) | <0.0001 |

| Serum albumin (+1 g/dL increase) | 0.43 (0.41, 0.46) | <0.0001 | 0.45 (0.42, 0.48) | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine (+1 mg/dL increase) | 0.95 (0.94, 0.96) | <0.0001 | 0.92 (0.91, 0.93) | <0.0001 |

| TIBC (+50 mg/dL increase) | 0.89 (0.86, 0.92) | <0.0001 | 0.89 (0.86, 0.92) | <0.0001 |

| Bicarbonate (+1 mg/dL increase) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.96 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.27 |

| Phosphorus (+1 mg/dL increase) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 0.45 |

| Calcium (+1 mg/dL increase) | 0.95 (0.92, 0.99) | 0.006 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.27 |

| Ferritin (+100 ng/mL increase) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.023 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | <0.0001 |

| Iron saturation ratio (+10 increase) | 0.74 (0.72, 0.76) | <0.0001 | 0.74 (0.72, 0.76) | <0.0001 |

| Blood hemoglobin (+1 g/dL increase) | 0.71 (0.69, 0.72) | <0.0001 | 0.71 (0.70, 0.73) | <0.0001 |

| WBC (+103/μL increase) | 1.39 (1.37, 1.40) | <0.0001 | 1.40 (1.38, 1.42) | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocyte (+10% of WBC increase) | 0.72 (0.69, 0.75) | <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.66, 0.72) | <0.0001 |

| ESA dose (+1000 units/wk increase) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | <0.0001 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.02) | <0.0001 |

ESA, erythropoietin stimulating agent; TIBC, total-iron-binding content; WBC, white blood cell.

Case-mix–adjusted models include adjustment for age, sex, diabetes mellitus, standardized mortality ratio, race, dialysis vintage, primary insurance, marital status, dialysis dose, dialysis catheter, and baseline comorbid states.

The association of a priori selected platelet count categories with the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause death via Cox regression models is shown in Figure 2, A and B. Compared with patients with a platelet count between 150 and <200 × 103/μL (reference), the unadjusted odds of cardiovascular death in 40,797 hemodialysis patients with platelet counts between 300 and <350, 350 and <400, and ≥ 400 × 103/μL were 7%, 15%, and 25% higher (P < 0.05), respectively. These U-shaped associations persisted after case-mix adjustment; however, further adjustment for MICS abolished, in some ranges even reversed, the association. Similar associations were observed with all-cause mortality (Figure 2A). We found similar results when we examined the association between platelet count (restricted to 150 to <500 × 103/μL) and mortality association using fractional polynomials and restricted cubic splines (OSM; Figure 4). Every 100 × 103/μL increase in platelet count was associated with a 13% higher risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.16; P < 0.001) and a 14% higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.12, 1.16; P < 0.001) in our case-mix model (Table 3). Further adjustment for MICS reversed the association, both in cardiovascular mortality (HR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.92, 0.98; P = 0.003) and in all-cause mortality (HR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.94, 0.98; P < 0.001).

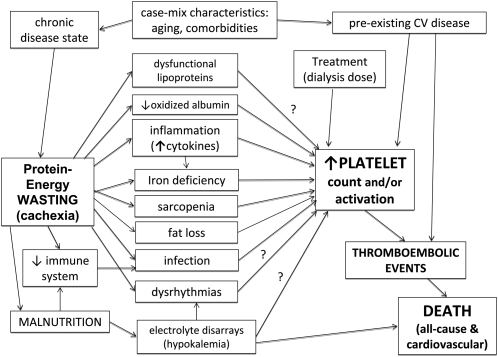

FIGURE 4.

Potential pathophysiologic mechanism of how cachexia leads to death. CV, cardiovascular.

TABLE 3.

HRs (and 95% CIs) of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality associated with each 100 × 103/μL increase in platelet count in Cox regression analyses in 40,797 long-term hemodialysis patients who were observed over a 6-y observation period (July 2001–June 2007)1

| Minimally adjusted2(n = 40,697) |

+ Case-mix adjusted3(n = 40,697) |

+ MICS adjusted4(n = 40,697) |

||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| All-cause mortality | 1.093 (1.074, 1.114) | <0.001 | 1.143 (1.122, 1.164) | <0.001 | 0.960 (0.941, 0.980) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease mortality | 1.073 (1.042, 1.104) | <0.001 | 1.125 (1.093, 1.159) | <0.001 | 0.952 (0.921, 0.983) | 0.003 |

MICS, malnutrition-inflammation cachexia syndrome.

Adjusted for entry calendar quarter (quarter 1 through quarter 20).

Adjusted for entry calendar quarter plus age, sex, 10 preexisting comorbid states, categories of dialysis vintage, primary insurance, marital status, the standardized mortality ratio of the dialysis clinic during entry quarter, dialysis dose as indicated by Kt/V (single pool), presence or absence of a dialysis catheter, and residual renal function during the entry quarter (ie, urinary urea clearance).

Adjusted for all of the covariates in the case-mix model plus BMI, the average dose of erythropoietin stimulating agent, total nitrogen appearance—also known as normalized protein catabolic rate—as an indicator of daily protein intake, serum albumin, serum total-iron-binding capacity, serum ferritin, serum creatinine, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, serum bicarbonate, peripheral white blood cell count, lymphocyte percentage, and iron saturation ratio.

Similar results were found when the mortality-predictability of a high platelet count (150–300 × 103/μL compared with ≥300 × 103/μL) was examined across different subgroups of patients (see forest plots in Figure 3, A and B). The unadjusted cardiovascular death HRs were above unity in almost all examined subgroups, which indicated a higher risk of poor cardiovascular outcomes with higher platelet counts. These associations persisted after case-mix adjustment in almost all examined subgroups; however, further adjustment for MICS abolished and in some ranges even reversed the association. Similar associations were observed with all-cause mortality (Figure 3B).

DISCUSSION

In a contemporary cohort of 40,787 adult hemodialysis patients, we found that higher platelet counts were associated with correlates of renal cachexia, including lower serum albumin and creatinine concentrations, lower blood hemoglobin and lymphocyte percentages, lower nPNA (nPCR) values (reflecting lower dietary protein intake), lower Kt/V values, and higher erythropoietin doses. Compared with patients with a platelet count between 150 and 200 × 103/μL as the reference, the all-cause and cardiovascular death risk were incrementally higher across higher platelet count categories. Whereas the cardiovascular death risk of a higher platelet count persisted after case-mix adjustment, further adjustment for surrogates of renal cachexia nullified or even reversed the associations. These findings may have important clinical implications, because they advance the hypothesis that a higher platelet count is a predictor of cardiovascular death risk in hemodialysis patients, but that its association with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality is almost fully accounted for by the renal cachexia (Figure 4).

In our study, we found that a higher platelet count was associated with markers of MICS, including a lower dietary protein intake, a lower dialysis dose, and a higher ESA dose. To the best of our knowledge only a few studies have examined platelet counts, MICS, and outcomes in ESRD populations (24, 25). In this study we found that a higher ESA dose and a lower hemoglobin concentration were associated with a higher platelet concentration. Streja et al (25) found that a high ESA dose can cause relative thrombocytosis by promoting iron depletion in hemodialysis patients. In the same way, in a prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial, including 244 hemodialysis patients, Kaupke et al (26) showed that administration of a relatively high dose of recombinant erythropoietin significantly increased the platelet count. These observations suggest a potential explanation for the dissociation of higher ESA dose and poor outcomes.

We found that a higher platelet count was associated with lower serum albumin and creatinine concentrations, a lower lymphocyte count, and a lower nPNA (nPCR) value as a surrogate of lower dietary protein intake. A similar trend was found with Kt/V, in that the lower Kt/V was associated with a higher platelet count. Serum albumin is a marker of both PEW and inflammation in hemodialysis patients (27); low nPNA (nPCR) is also related to malnutrition and poor outcome (28), and serum creatinine is a surrogate of muscle mass in hemodialysis patients (18, 29, 30). A low lymphocyte percentage is also a malnutrition marker (31). Our findings suggest that a high platelet count correlates with MICS. A potential explanation for these associations is the modulation by inflammatory cytokines. Platelets are generated from fragmentation of the cytoplasm of megakaryocytes, which are the byproduct of proliferation and differentiation of colony-forming unit megakaryocytes (32). Megakaryopoiesis is regulated by inflammation factors such as IL-6, IL-11, and leukemia inhibitor factor, which predominantly support megakaryocyte maturation (33). Similarly, through the actions of IL-6 and other cytokines, inflammation, which is common in ESRD patients, can cause reactive thrombocytosis (34). Previous studies have clearly shown elevated concentration of inflammatory cytokines in hemodialysis patients with renal cachexia, also known as MICS (8, 35, 36).

We also found that relative thrombocytosis is a predictor of both all-cause and cardiovascular death risk in hemodialysis patients, but that its mortality predictability is fully accounted for by the surrogates of renal cachexia. Platelet reactivity plays a central role in thromboembolic events, especially in the setting of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of death in ESRD patients (3). In the early 1970s, Evans et al (37) described the platelet function abnormalities in uremic patients. Moreover, the high platelet reactivity determined in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease is associated with a higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events (38). To this end, antiplatelet therapy is used to decrease the occurrence of thromboembolic events (5), even though, Chan et al (39) recently found no benefit associated with use of antiplatelet therapy in this population, and perhaps higher mortality, which may be related to confounding by indication. In peritoneal dialysis patients with diabetes, thrombocytosis is associated with the severity of cardiovascular disease (6). In the current study we analyzed platelet counts rather than the level of platelet function. Cardiovascular mortality may still be independently associated with platelet function. Previous studies found that high ex vivo platelet reactivity is associated with ischemic events (7); however, this has not been studied in patients with ESRD. Furthermore, studies are needed to answer this question.

Although surrogates of renal cachexia are consistently associated with mortality in ESRD patients (8, 11), it is not clear through which mechanisms renal cachexia and death are related. da Silva et al (40) reported that platelet aggregation induced by collagen is impaired in patients with well-nourished chronic renal failure relative to malnourished patients and control subjects. Plasma l-arginine concentrations are reduced in chronic renal failure patients and are even lower in malnourished patients. The absence of the adaptive response in the l-arginine–nitric oxide pathway in platelets from malnourished chronic renal failure patients may account for the enhanced occurrence of thromboembolic events in these patients (40). Moreover, reduced plasma l-arginine and nitric oxide production and elevated cytokine concentrations are associated with increased aggregability of platelets taken from malnourished uremic patients (41). In our unadjusted and case-mix adjusted model, a higher platelet count was associated with higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Malnourished chronic renal failure patients had a higher platelet count and increased aggregability of platelets, which can enhance thromboembolic events—the leading cause of death in ESRD patients (3). After adjustment for MICS, the association between platelet number and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality did not exist. These findings can advance the hypothesis that renal cachexia increases mortality via increasing platelet count and activity. Our hypothesis of a platelet-mortality association in ESRD patients and its link to wasting syndrome is shown in Figure 4. In the MICS-adjusted model, we accounted for the intermediary factors in the pathway between renal cachexia and thrombocytosis, resulting in abolishment of the mortality predictability of high platelet count. This hypothesis needs to be examined in randomized controlled trials.

Our study was limited by its observational nature. Like all observational studies, this analysis cannot distinguish direct causation from confounding. Another limitation of our study was that no antiplatelet medication was included in our analysis. However, Chan et al (39) found no benefit associated with the use of antiplatelet therapy in this population, and perhaps higher mortality, which may be related to confounding by indication. Additionally, missing medications, no platelet function, and residual measured or unmeasured confounders could have accounted for some or all of the relations. Moreover, we did not have data for other platelet variables, which may relate to the activation status of the platelets, such as impedance compared with optical measurements, immunological measurements, platelet clumping, or other biomarkers of platelet activation (42, 43). An additional weakness of our study was that we had only one platelet measurement; therefore, we were not able to analyze the association of outcome and platelet number changes over time. An important strength of our study was its large sample size, which allowed us to account for important covariates in the multivariate analyses and to examine specific associations, thus providing points of focus in future studies. To the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to examine the association of platelet count and all-cause and cardiovascular survival in hemodialysis patients.

In conclusion, a higher platelet count is associated with surrogates of renal cachexia and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. However, the association of platelet count with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality is accounted for by indexes of renal cachexia. Whereas the hypothesis that renal cachexia increases mortality via increasing platelet counts needs to be examined in additional studies, the findings do not necessarily imply a causal relation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors' responsibilities were as follows—MZM, ES, CPK, ARN, KCN, and GCF: contributed to analyzing and interpreting the data and writing the manuscript; MJB, MK, and SDA: contributed to analyzing and interpreting the data; KK-Z: managed the data entry, contributed to analyzing and interpreting the data and writing the manuscript, and designed, organized, and coordinated the study. None of the funders had any part in the design, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of the research. None of the authors had a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

CHF, congestive heart failure; ESA, erythropoietin stimulating agent; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; MICS, malnutrition-inflammation cachexia syndrome; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; nPNA, normalized protein equivalent of total nitrogen appearance; PEW, protein-energy wasting; TIBC, total-iron-binding capacity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;41:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anker SD, Negassa A, Coats AJ, Afzal R, Poole-Wilson PA, Cohn JN, Yusuf S. Prognostic importance of weight loss in chronic heart failure and the effect of treatment with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: an observational study. Lancet 2003;361:1077–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, Chavers BM, Gilbertson D, Ishani A, Kasiske BL, Liu J, Mau LW, McBean M, et al. Excerpts from US Renal Data System 2009 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis 2010;55:S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zile MR, Gaasch WH, Anand IS, Haass M, Little WC, Miller AB, Lopez-Sendon J, Teerlink JR, White M, McMurray JJ, et al. Mode of death in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: results from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-Preserve) trial. Circulation 2010;121:1393–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aljaroudi WA, Halabi AR, Harrington RA. Platelet inhibitor therapy for patients with cardiovascular disease: looking toward the future. Curr Hematol Rep 2005;4:397–404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokunbi DO, Wadhwa NK, Suh H. Vascular disease outcome and thrombocytosis in diabetic and nondiabetic end-stage renal disease patients on peritoneal dialysis. Adv Perit Dial 1994;10:77–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurbel PA. The relationship of platelet reactivity to the occurrence of post-stenting ischemic events: emergence of a new cardiovascular risk factor. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2006;7(suppl 4):S20–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Block G, Humphreys MH. A malnutrition-inflammation score is correlated with morbidity and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;38:1251–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaizu Y, Ohkawa S, Odamaki M, Ikegaya N, Hibi I, Miyaji K, Kumagai H. Association between inflammatory mediators and muscle mass in long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;42:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouque D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple J, Cano N, Chauveau P, Cuppari L, Franch H, Guarnieri G, Ikizler TA, Kaysen G, et al. A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2008;73:391–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rambod M, Bross R, Zitterkoph J, Benner D, Pithia J, Colman S, Kovesdy CP, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of Malnutrition-Inflammation Score with quality of life and mortality in hemodialysis patients: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:298–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segal JB, Moliterno AR. Platelet counts differ by sex, ethnicity, and age in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 2006;16:123–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Real JM, Vendrell J, Richart C, Gutierrez C, Ricart W. Platelet count and interleukin 6 gene polymorphism in healthy subjects. BMC Med Genet 2001;2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debili N, Masse JM, Katz A, Guichard J, Breton-Gorius J, Vainchenker W. Effects of the recombinant hematopoietic growth factors interleukin-3, interleukin-6, stem cell factor, and leukemia inhibitory factor on the megakaryocytic differentiation of CD34+ cells. Blood 1993;82:84–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molnar MZ, Lukowsky LR, Streja E, Dukkipati R, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Blood pressure and survival in long-term hemodialysis patients with and without polycystic kidney disease. J Hypertens . 2011;28:2475–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Norris KC, Mehrotra R, Nissenson AR, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of cumulatively low or high serum calcium levels with mortality in long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 2010;32:403–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Nissenson AR, Mehrotra R, Streja E, Van Wyck D, Greenland S, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of hemodialysis treatment time and dose with mortality and the role of race and sex. Am J Kidney Dis 2010;55:100–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Oreopoulos A, Noori N, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Krishnan M, Kopple JD, Mehrotra R, et al. The obesity paradox and mortality associated with surrogates of body size and muscle mass in patients receiving hemodialysis. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:991–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Mehrotra R, Lukowsky LR, Streja E, Ricks J, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Greenland S, et al. Impact of race on hyperparathyroidism, mineral disarrays, administered vitamin D mimetic, and survival in hemodialysis patients. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25:2724–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longenecker JC, Coresh J, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Martin AA, Fink NE, Powe NR. Validation of comorbid conditions on the end-stage renal disease medical evidence report: the CHOICE study. Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000;11:520–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Regidor DL, McAllister CJ, Michael B, Warnock DG. Time-dependent associations between iron and mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:3070–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Regidor DL, McAllister CJ, Michael B, Warnock DG. Association of morbid obesity and weight change over time with cardiovascular survival in hemodialysis population. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;46:489–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Kilpatrick RD, McAllister CJ, Shinaberger CS, Gjertson DW, Greenland S. Revisiting mortality predictability of serum albumin in the dialysis population: time dependency, longitudinal changes and population-attributable fraction. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20:1880–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaziri ND. Thrombocytosis in EPO-treated dialysis patients may be mediated by EPO rather than iron deficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:733–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Greenland S, Kopple JD, McAllister CJ, Nissenson AR, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Erythropoietin, iron depletion, and relative thrombocytosis: a possible explanation for hemoglobin-survival paradox in hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;52:727–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaupke CJ, Butler GC, Vaziri ND. Effect of recombinant human erythropoietin on platelet production in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 1993;3:1672–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Review article: biomarkers of clinical outcomes in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2009;14:408–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shinaberger CS, Kilpatrick RD, Regidor DL, McAllister CJ, Greenland S, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Longitudinal associations between dietary protein intake and survival in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;48:37–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noori N, Kopple JD, Kovesdy CP, Feroze U, Sim JJ, Murali SB, Luna A, Gomez M, Luna C, Bross R, et al. Mid-arm muscle circumference and quality of life and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:2258–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noori N, Kovesdy CP, Dukkipati R, Kim Y, Duong U, Bross R, Oreopoulos A, Luna A, Benner D, Kopple JD, et al. Survival predictability of lean and fat mass in men and women undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1060–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovesdy CP, George SM, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Outcome predictability of biomarkers of protein-energy wasting and inflammation in moderate and advanced chronic kidney disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:407–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segal GM, Stueve T, Adamson JW. Analysis of murine megakaryocyte colony size and ploidy: effects of interleukin-3. J Cell Physiol 1988;137:537–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaushansky K, Lok S, Holly RD, Broudy VC, Lin N, Bailey MC, Forstrom JW, Buddle MM, Oort PJ, Hagen FS, et al. Promotion of megakaryocyte progenitor expansion and differentiation by the c-Mpl ligand thrombopoietin. Nature 1994;369:568–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaser A, Brandacher G, Steurer W, Kaser S, Offner FA, Zoller H, Theurl I, Widder W, Molnar C, Ludwiczek O, et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates thrombopoiesis through thrombopoietin: role in inflammatory thrombocytosis. Blood 2001;98:2720–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Humphreys MH, Block G. Comparing outcome predictability of markers of malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:1507–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molnar MZ, Keszei A, Czira ME, Rudas A, Ujszaszi A, Haromszeki B, Kosa JP, Lakatos P, Sarvary E, Beko G, et al. Evaluation of the malnutrition-inflammation score in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2010;56:102–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans EP, Branch RA, Bloom AL. A clinical and experimental study of platelet function in chronic renal failure. J Clin Pathol 1972;25:745–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angiolillo DJ, Bernardo E, Sabate M, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Costa MA, Palazuelos J, Hernandez-Antolin R, Moreno R, Escaned J, Alfonso F, et al. Impact of platelet reactivity on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:1541–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan KE, Lazarus JM, Thadhani R, Hakim RM. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet usage associates with mortality among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:872–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.da Silva CD, Brunini TM, Reis PF, Moss MB, Santos SF, Roberts NB, Ellory JC, Mann GE, Mendes-Ribeiro AC. Effects of nutritional status on the L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway in platelets from hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2005;68:2173–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunini TM, Mendes-Ribeiro AC, Ellory JC, Mann GE. Platelet nitric oxide synthesis in uremia and malnutrition: a role for L-arginine supplementation in vascular protection? Cardiovasc Res 2007;73:359–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitz G, Rothe G, Ruf A, Barlage S, Tschope D, Clemetson KJ, Goodall AH, Michelson AD, Nurden AT, Shankey TV. European Working Group on Clinical Cell Analysis: consensus protocol for the flow cytometric characterisation of platelet function. Thromb Haemost 1998;79:885–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayward CP, Moffat KA, Raby A, Israels S, Plumhoff E, Flynn G, Zehnder JL. Development of North American consensus guidelines for medical laboratories that perform and interpret platelet function testing using light transmission aggregometry. Am J Clin Pathol 2010;134:955–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.