Abstract

Background: Strategies are needed to increase children's intake of a variety of vegetables, including vegetables that are not well liked.

Objective: We investigated whether incorporating puréed vegetables into entrées to reduce the energy density (ED; in kcal/g) affected vegetable and energy intake over 1 d in preschool children.

Design: In this crossover study, 3- to 5-y-old children (n = 40) were served all meals and snacks 1 d/wk for 3 wk. Across conditions, entrées at breakfast, lunch, dinner, and evening snack were reduced in ED by increasing the proportion of puréed vegetables. The conditions were 100% ED (standard), 85% ED (tripled vegetable content), and 75% ED (quadrupled vegetable content). Entrées were served with unmanipulated side dishes and snacks, and children were instructed to eat as much as they liked.

Results: The daily vegetable intake increased significantly by 52 g (50%) in the 85% ED condition and by 73 g (73%) in the 75% ED condition compared with that in the standard condition (both P < 0.0001). The consumption of more vegetables in entrées did not affect the consumption of the vegetable side dishes. Children ate similar weights of food across conditions; thus, the daily energy intake decreased by 142 kcal (12%) from the 100% to 75% ED conditions (P < 0.05). Children rated their liking of manipulated foods similarly across ED amounts.

Conclusion: The incorporation of substantial amounts of puréed vegetables to reduce the ED of foods is an effective strategy to increase the daily vegetable intake and decrease the energy intake in young children. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01252433.

INTRODUCTION

Research has consistently shown that vegetable consumption in children is well below recommended amounts (1–4). One reason suggested for the low vegetable consumption is that many children do not like vegetables because of the inherent sensory properties of vegetables, particularly taste and texture (5–8). Strategies, such as increasing the vegetable portion size, have been shown to be effective at promoting vegetable intake in children when the vegetables are well liked, such as with carrot sticks or tomato soup (9, 10); however, strategies are needed to increase the consumption of a wide variety of vegetables. The covert addition of vegetables to foods so that the palatability of the foods is not affected may be an effective method to increase vegetable intake in children, regardless of their liking of vegetables. The present study examined the effect of increasing the proportion of vegetables in entrées served to children over a day on vegetable and energy intakes.

The substitution of low-energy-dense vegetables for more energy-dense meal components, such as starches or meat, will lower the energy density (ED; in kcal/g) of a food and can lead to a reduction in the energy intake. Several studies have shown that people tended to eat a consistent weight of food, and therefore, the reduction of dietary ED led to a reduction in the energy intake (11–13). This result has been shown in studies in adults (11–13) and children (14–17). In one study, a decrease of the ED of an entrée by 25% significantly reduced the children's energy intake of the entrée by 25% and decreased the energy intake of the meal by 17% (16). Another study has shown that children reduced their energy intake by 14% over 2 d when meals were reduced in ED by 25% (17). In these studies, ED was modified by using several techniques, including reductions in fat and sugar and increases in fruit and vegetable content. To our knowledge, the current study was the first to test the effect on children's energy intake of reducing the ED of an entrée by increasing solely the proportion of vegetables.

In the current study, entrées at breakfast, lunch, and dinner were varied in ED by increasing the proportion of puréed vegetables. The following 3 amounts of ED were tested: 100% ED (the standard recipe), 85% ED, and 75% ED. Unmanipulated side dishes and snacks were provided at meals and snack times throughout the day so that children had opportunities to compensate for reductions in the energy intake. We hypothesized that children would eat a consistent weight of the entrées across conditions. Thus, as the ED of the entrees was reduced by increasing the proportion of vegetables, the vegetable intake would increase, and the energy intake would decrease. In addition, it was hypothesized that, despite opportunities for compensation, children would consume a consistent weight of unmanipulated foods, and as a result, the increase in vegetable consumption and the decrease in the energy intake would persist over the day.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Experimental design

A within-subject crossover design was used to test the effect of varying the vegetable contents of entrées on vegetable and energy intakes of preschool-aged children. Children were provided all of their foods, including breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snack foods, 1 d/wk for 3 wk. Across test days, entrées at breakfast, lunch, dinner, and evening snack were varied in ED through the incorporation of vegetables (100% ED, 85% ED, and 75% ED); unmanipulated side dishes and snacks were also provided. All foods and beverages were consumed ad libitum. The order of presentation of the 3 conditions was randomly assigned to each participant. Random orders were generated with computer software and assigned to a list of participant identification numbers. During the week before the study, 1 d was used to acquaint children, parents, and teachers with the test-day procedures; no data were collected on this day. The study was conducted between January and May 2010.

Participants

Recruitment began by distributing letters to parents with children aged 3–6 y who were enrolled in daycare at the Bennett Family Center or the Child Development Laboratory at the University Park campus of The Pennsylvania State University. Children with an allergy to the foods being served were not eligible to participate in the study. Parents and guardians provided informed written consent for both their own participation and that of their child. The Pennsylvania State University Office for Research Protections reviewed and approved all procedures.

A power analysis was performed to determine the number of children needed in the study on the basis of a previous study in a similar population of children (17). The minimal clinically relevant difference in the daily energy intake was assumed to be 120 kcal, which was ∼10% of the recommended daily energy intake for children of this age group (18). It was estimated that 34 children would allow the detection of this difference with 80% power by using a 2-sided test with a significance level of 0.05. Forty-nine children were enrolled in the study; however, 9 children did not complete the study because of a difficulty following the protocol. The final sample consisted of 40 children (19 boys and 21 girls). This sample represented ∼35% of the eligible children in the daycare centers.

Experimental menu

The 3 experimental entrées (Table 1) were manipulated by adding puréed vegetables to a standard recipe (100% ED condition) to reduce the ED by either 15% (85% ED condition) or 25% (75% ED condition). Manipulated entrées were zucchini bread at breakfast, pasta with tomato-based sauce at lunch, and chicken noodle casserole at dinner and evening snack. These foods were chosen because they were similar to foods typically served at the daycare facilities, and vegetable contents could be manipulated while maintaining a similar appearance, taste, and texture. The reduction in ED was achieved by substituting low-energy-dense vegetables (zucchini, cauliflower, broccoli, tomatoes, and squash) for ingredients higher in ED; therefore, as the vegetable content increased, the amount of other ingredients decreased. The average amount of puréed vegetables added to the entrées (per 100 g entrée) was 6.0 g in the 100% ED condition, 22 g in the 85% ED condition, and 32 g in the 75% ED condition. A bomb calorimeter (model 1261; Parr Instrument Co) was used to confirm that the planned reduction in ED was achieved.

TABLE 1.

Manipulated entrées served on test days to preschool children in a study that tested the effect of adding vegetables to reduce the energy density (ED; in kcal/g) of entrées on energy and vegetable intakes1

| Condition |

|||

| 100% ED (standard) | 85% ED | 75% ED | |

| Breakfast: zucchini bread (120 g) | |||

| ED (kcal/g) | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.0 |

| Energy content (kcal) | 480 | 408 | 360 |

| Puréed vegetable content (g)2 | 11 | 28 | 39 |

| Lunch: pasta and sauce (300 g) | |||

| ED (kcal/g) | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Energy content (kcal) | 510 | 420 | 390 |

| Puréed vegetable content (g)3 | 10 | 65 | 94 |

| Dinner: chicken noodle casserole (300 g) | |||

| ED (kcal/g) | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Energy content (kcal) | 480 | 420 | 360 |

| Puréed vegetable content (g)4 | 19 | 67 | 98 |

| Evening snack: chicken noodle casserole (200 g) | |||

| ED (kcal/g) | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Energy content (kcal) | 320 | 280 | 240 |

| Puréed vegetable content (g)4 | 12 | 45 | 65 |

Recipe information for manipulated foods can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Zucchini.

Broccoli, cauliflower, and tomato.

Cauliflower and squash.

In addition to the manipulated entrées, unmanipulated side dishes, snacks, and milk were served (Table 2) to provide nutritionally balanced meals in compliance with the Child Nutrition Program (19). The provision of vegetable side dishes also allowed for the examination of the effects of the vegetable intake from the entrée on the intake of cooked vegetable side dishes. Portion sizes of all items served to the children were based on consumption data from previous studies in this age group (9, 17). Children were served more than enough food to meet their energy needs (18). Including all foods and beverages served, the 100% ED condition provided 2992 kcal over the day, the 85% ED condition provided 2716 kcal over the day, and the 75% ED condition provided 2548 kcal over the day.

TABLE 2.

Unmanipulated snacks, side dishes, and beverages served on test days to preschool children in a study that tested the effect of adding vegetables to reduce the energy density of entrées on energy and vegetable intakes

| Portion served | Energy content | Energy density | |

| g | kcal | kcal/g | |

| Breakfast and afternoon snacks | |||

| Cereal bar1 | 37 | 130 | 3.5 |

| Breakfast side dishes | |||

| Mandarin oranges2 | 150 | 65 | 0.4 |

| Milk (1% fat)3 | 236 | 100 | 0.4 |

| Lunch side dishes | |||

| Broccoli4 | 60 | 17 | 0.3 |

| Applesauce2 | 150 | 63 | 0.4 |

| Milk (1% fat)3 | 236 | 100 | 0.4 |

| Dinner side dishes | |||

| Green beans5 | 60 | 17 | 0.3 |

| Pears2 | 150 | 72 | 0.5 |

| Milk (1% fat)3 | 236 | 100 | 0.4 |

| Evening snacks | |||

| String cheese6 | 28 | 70 | 2.5 |

| Crackers1 | 29 | 130 | 4.5 |

| Peaches2 | 150 | 60 | 0.4 |

| Milk (1% fat)3 | 236 | 100 | 0.4 |

Kellogg Sales Co.

Sysco Corp.

Schneider Valley Farms.

Birds Eye Foods Inc.

Hanover Foods Corp.

Lactalis American Group Inc.

Meal procedures

Children enrolled in the study were served breakfast, lunch, and afternoon snack in the daycare centers at their usual times. Dinner was also served at the daycare center, which differed from the usual practice at the facilities. At meal time, children were escorted to a common room in the daycare facilities where they ate at a table with 2–6 other children and one adult. When children finished eating, spilled or dropped food was returned to the correct dish, and the items were cleared. Food and beverage weights were recorded to the nearest 0.1 g with digital scales (PR5001 and XS4001S; Mettler-Toledo Inc). The consumption of foods and beverages was determined by subtracting postmeal weights from premeal weights. The manufacturers’ nutrition information and a standard food-composition database (20) were used to calculate energy and nutrient intakes and EDs.

Evening snacks were sent home with the children's parents or guardians; snacks included cheese and crackers, fruit, milk, and a small amount of the same entrée that was served at dinner. An additional entrée was included in case the other snacks were insufficient to satisfy any hunger that may have developed. Parents were instructed to allow their child to consume only the foods and beverages provided and to leave any remaining foods and beverages in the containers. Parents were also instructed to not let any other family members consume the provided foods and beverages. To minimize the likelihood that the children in the study would want to eat foods served to their siblings, evening snacks were also provided for siblings of study participants. Food and beverage containers were returned unwashed to the daycare center for postmeal weighing. A breakfast snack bar was provided to parents the evening before the test day for optional consumption the morning of the study day. Instructions regarding the breakfast snack were the same as those provided for the evening snack.

Food-liking assessments

Within 1 wk of the completion of all test meals, the children's liking of the 3 versions of each of the 3 experimental entrées was assessed by using a procedure developed by Birch (21–23). Children were instructed on the use of 3 cartoon faces to indicate whether they thought a food was yummy, okay, or yucky. After instruction, each child was presented with a food sample. The child was asked to taste the food and indicate their liking of the food by pointing to the appropriate face. Samples were tested at typical meal times; each child was presented with samples in a randomly assigned order. After children rated all 3 samples of one entrée, a rank-order preference assessment was performed. Each child selected their most and least preferred sample, which resulted in samples being assigned a rank of 1 (favorite), 2, or 3 (least favorite).

Demographic and anthropometric measures

Parents were asked to complete a questionnaire with 19 questions that assessed family demographics and the health status of their child. Body weight and height measurements of children were taken in ≤1 wk of the final test meal. The children's height and weight measurements were used to calculate their sex-specific BMI-for-age percentile and z score with a software program from the CDC (24).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using a mixed linear model with repeated measures (SAS version 9.1; SAS Institute). Fixed factors in the model were the entrée ED (100%, 85%, or 75%) and session number; subjects were treated as a random factor. The sex, food-acceptability ratings, and food-preference rankings of children were tested as factors in the model. Main outcome measures were the daily food, vegetable, and energy intakes. The vegetable intake was reported as weight and volume; the volume of one vegetable serving was defined as one-half cup (118 mL) of the chopped or sliced vegetable. Dietary ED was a secondary outcome and was calculated on the basis of the food intake without beverages (25). Individual children whose data were influential on the main outcomes in the mixed model were identified by using the procedure of Littell et al (26) on the basis of extreme values for the restricted likelihood distance, Cook's D statistic, or Covratio statistic.

ANCOVA was used to assess the influence of continuous subject variables (age, body weight, height, and BMI percentile) on the relation between entrée ED and the main study outcomes. t tests were used to test differences between girls and boys in ages, body weights, heights, BMI percentiles, and BMI z scores. Data are reported as means ± SEs, and results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

A total of 40 children (19 boys and 21 girls) completed the study. Data from one child were identified as having an undue influence on the results because of a high variability across meals, and therefore, the data were excluded from the analysis. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 3. The final group of 39 children had a mean age of 4.7 ± 0.1 y and a mean sex-specific BMI-for-age percentile of 55.9 ± 5.1; 10% of the children were overweight (n = 3) or obese (n = 1). The mean BMI percentile and BMI z score were significantly higher for girls than for boys (P < 0.05); otherwise, the mean age, height, and weight did not differ significantly between girls and boys. Of the 39 children, 28 children (72%) were white, 9 children (23%) were Asian, and 2 children (5%) were black or African American. Parents of the children had above average education levels and household incomes; ∼90% of mothers and 80% of fathers had a college degree, and 76% of households had an annual income >$50,000.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of children who participated in a study that tested the effect of reducing the entrée energy density by adding vegetables1

| Boys (n = 18) |

Girls (n = 21) |

|||

| Characteristic | Mean ± SE | Range | Mean ± SE | Range |

| Age (y) | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 3.7–6.1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 3.6–5.8 |

| Weight (kg) | 18.4 ± 0.9 | 15.6–28.2 | 18.4 ± 0.9 | 15.6–24.5 |

| Height (cm) | 107.9 ± 1.8 | 97.0–125.2 | 105.9 ± 1.6 | 94.0–114.4 |

| BMI z score2 | −0.1 ± 0.1a | −1.1–1.8 | 0.5 ± 0.1b | −0.4–2.3 |

| Sex-specific BMI-for-age percentile2 | 46.0 ± 8.1a | 12.5–96.8 | 66.6 ± 5.1b | 32.9–98.8 |

Different superscript letters within a row indicate a significant difference between sexes by using an unpaired t test (P < 0.05).

Calculated from height, weight, and age (24).

Food intake

There was no significant difference in the food intake (in g) of manipulated entrées across different ED conditions (Table 4). In addition, there was no difference in the weight of food consumed from side dishes, snacks, or beverages across conditions. Therefore, the children ate a consistent weight of food at each meal and over the day regardless of the ED of entrées.

TABLE 4.

Food and energy intakes of 39 children over 1 d when all entrées served were 100%, 85%, or 75% of the standard energy density (ED)1

| Conditions | |||

| 100% ED | 85% ED | 75% ED | |

| Food intake (g) | |||

| Manipulated entrées | 270.4 ± 26.5 | 295.0 ± 29.6 | 289.8 ± 26.7 |

| Unmanipulated foods | 403.0 ± 32.8 | 404.8 ± 33.5 | 354.8 ± 36.2 |

| Total foods | 694.7 ± 37.9 | 722.3 ± 47.9 | 664.5 ± 48.7 |

| Energy intake (kcal) | |||

| Manipulated entrées | 606.4 ± 50.9a | 572.9 ± 46.9a,b | 512.5 ± 40.0b |

| Unmanipulated foods | 375.0 ± 21.8 | 403.7 ± 19.6 | 353.3 ± 23.5 |

| Total foods | 1022.9 ± 52.4a | 1015.2 ± 53.5a,b | 889.4 ± 52.0b |

| ED (kcal/g) | |||

| Manipulated entrées | 2.35 ± 0.09a | 2.07 ± 0.07b | 1.88 ± 0.08c |

| Unmanipulated foods | 1.09 ± 0.09 | 1.17 ± 0.10 | 1.19 ± 0.09 |

| Total foods | 1.53 ± 0.07a | 1.48 ± 0.06b | 1.43 ± 0.07b |

All values are means ± SEMs. Values in the same row with different superscript letters are significantly different (P < 0.05, mixed linear model with repeated measures with a Tukey-Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons).

Vegetable intake

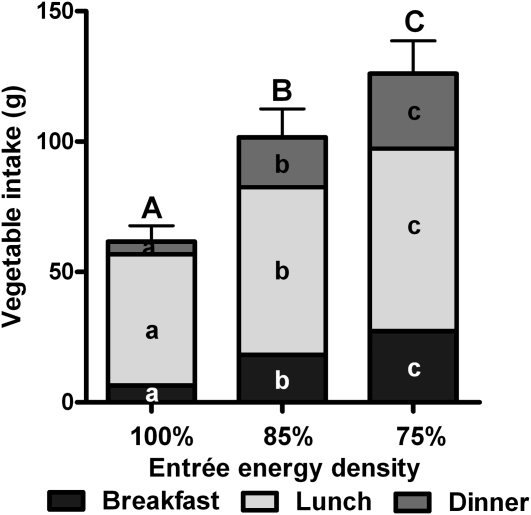

The incorporation of vegetables into entrées resulted in an increase in the vegetable intake at each meal and over the day (P < 0.01; Figure 1). The amount of vegetables consumed daily from entrées was, on average, 65 ± 6 g in the 100% ED condition, 109 ± 12 g in the 85% ED condition, and 132 ± 13 g in the 75% ED condition. Compared with the standard condition, the vegetable intake from entrées increased by 68% and 103% in the 85% ED and 75% ED conditions, respectively. The amount of vegetables consumed from entrées was equivalent to 0.8 vegetable servings in the 100% ED condition, 1.5 vegetable servings in the 85% ED condition, and 1.9 vegetable servings in the 75% condition. The increase of the vegetable intake from entrées did not affect the consumption of vegetable side dishes served at lunch and dinner; therefore, vegetable consumption over the day increased as the vegetable content of entrées increased (P < 0.0001). The average daily vegetable consumption was 101 ± 8 g, 152 ± 12 g, and 174 ± 13 g in the 100% ED, 85% ED, and 75% ED conditions, respectively. This consumption represented an increase in the daily vegetable intake of 50% and 73% in the 85% and 75% ED conditions compared with in the standard condition.

FIGURE 1.

Mean (±SEM) weight of vegetables consumed from entrées at breakfast, lunch, and dinner by 39 preschool children. Entrées were varied in energy density across conditions by incorporating additional vegetables. Different letters for values for the same outcome indicate a significant difference by using a mixed linear model with repeated measures and Tukey-Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons (P < 0.001). The vegetable intake from the entrée provided at evening snack was negligible and did not vary significantly across conditions.

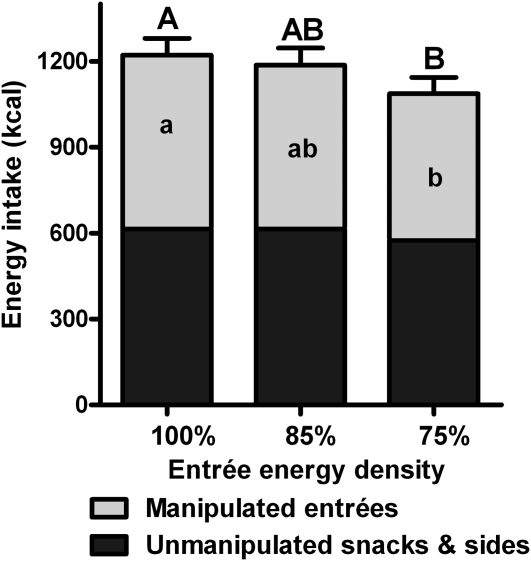

Energy intake

Because children consumed a consistent weight of food across conditions, the reduction of the ED of entrées had a significant effect on the energy intake over the day (Figure 2). The reduction of the ED by 25% resulted in a difference in the energy intake of 142 kcal (P = 0.030). This amount equated to a reduction in the daily energy intake of ∼12%. The energy intake in the 85% ED condition was not significantly different from that in the other conditions (P > 0.10). There was no difference in the average energy intake from unmanipulated side dishes, snacks, and beverages across conditions; therefore, the reduction in the energy intake was a result of the change in the entrée ED. The mean ED of all foods consumed over the day decreased as the entrée ED decreased (P = 0.003; Table 4).

FIGURE 2.

Mean (±SEM) energy intake consumed from manipulated entrées and unmanipulated foods and beverages over 1 d by 39 preschool children. Entrées were varied in energy density across conditions by incorporating additional vegetables. Different letters for values for the same outcome indicate a significant difference by using a mixed linear model with repeated measures and Tukey-Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05).

Influence of food liking and subject characteristics

Of the 39 children that completed the study, 30 children completed the liking and preference assessments (Table 5). All versions of entrées were generally well liked as indicated by >70% of the children rating them as yummy or okay. The children's ratings of liking for an entrée did not significantly influence their consumption of that entrée. Furthermore, ratings of liking for the entrée did not significantly influence the relation between the ED of the entrée and the energy intake at the meal. Preference rankings of entrées also indicated that different versions of the entrées were liked; each entrée was rated as the favorite by approximately one-third of the children (Table 5). Preference rankings of entrées did not significantly influence the consumption of entrées or the relation between entrée ED and meal energy intake.

TABLE 5.

Liking ratings and preference rankings of each of the manipulated entrées that varied in energy density (ED) and were served to children (n = 30)

| Liking rating |

Preference ranking |

|||||

| Yummy | Okay | Yucky | Favorite | Second favorite | Least favorite | |

| % | % | |||||

| Breakfast bread | ||||||

| 100% ED | 69 | 19 | 12 | 34 | 34 | 32 |

| 85% ED | 78 | 19 | 3 | 38 | 31 | 31 |

| 75% ED | 69 | 25 | 6 | 28 | 34 | 38 |

| Lunch pasta | ||||||

| 100% ED | 63 | 33 | 3 | 33 | 40 | 27 |

| 85% ED | 67 | 27 | 6 | 37 | 37 | 26 |

| 75% ED | 63 | 20 | 17 | 30 | 23 | 47 |

| Dinner and evening snack casserole | ||||||

| 100% ED | 63 | 17 | 20 | 29 | 29 | 42 |

| 85% ED | 63 | 30 | 7 | 42 | 42 | 16 |

| 75% ED | 50 | 23 | 27 | 29 | 29 | 42 |

An ANCOVA indicated that the effects of the entrée ED on food and energy intakes were not significantly influenced by the children's ages, body weights, heights, or BMI percentiles. However, there may have been an insufficient statistical power to detect a significant covariation of these subject variables.

DISCUSSION

The current study showed that the incorporation of puréed vegetables into foods could be an effective strategy to increase children's vegetable intake and decrease their energy intake. When a substantial amount of vegetables was added to all entrées served over the day to reduce the ED by 15% and 25%, children consumed a consistent amount of food. Consequently, in the 85% ED and 75% ED conditions, the vegetable intake from entrées increased by 68% and 103%, respectively, and the entrée energy intake decreased by 5% and 15%, respectively. The decrease in the energy intake persisted over the day even though children were given opportunities to compensate by consuming greater amounts of unmanipulated side dishes and snacks. The use of puréed vegetables to reduce the ED of foods has the potential to have a large impact on children's vegetable consumption as well as to reduce energy intake.

Strategies to increase children's vegetable intake have been the objective of several recent studies (9, 10, 27). One strategy that has been successful at enhancing vegetable consumption in preschool children is to serve larger portions of vegetables (9). However, this method appears to be limited by the palatability of the vegetables (ie, if a vegetable is not liked by a child, the serving of a larger portion is unlikely to lead to a greater intake) (27). Strategies are needed that can increase intake of a variety of vegetables, including vegetables that are not commonly well liked by children. In the present study, broccoli, cauliflower, tomatoes, squash, and zucchini were covertly added to familiar entrées so that the appearance, flavor, and texture of the original recipes were maintained. Liking and preference assessments indicated that palatability ratings of entrées with added vegetables were similar to those of the standard recipes. Intake results also confirmed this similarity in that the children ate a consistent weight of the entrées even when there was a substantial increase in the vegetable content. With the use of puréed vegetables to decrease the entrée ED by 25%, the children's daily vegetable intake increased from about one-half of the recommended amount to nearly the full recommended amount. This study has shown that substantial amounts of a variety of vegetables can be incorporated into foods without adversely affecting the amount of the entrée eaten, and that this technique has the potential to make a significant contribution to the number of children who meet their recommended intake of vegetables.

Although covertly incorporating vegetables into foods can have a beneficial effect on children's vegetable intake, it should not be the only way that vegetables are served to children. Because the liking of an originally disliked vegetable can be increased through repeated exposure (28–30), it is important to use several strategies to ensure that children experience different forms of vegetables, especially whole vegetables. Serving a variety of forms and types of vegetables has the potential to promote intake as well as to improve liking. In the current study, the intake of the vegetable side dishes was not affected by enhancing the vegetable content of the entrées; thus, these 2 sources combined to increase the children's vegetable consumption. Other studies have shown that children's vegetable intake is increased by serving vegetables at the start of a meal without the presence of competing foods (9, 10) and by serving large portions of well-liked vegetables (9, 10, 27). A variety of strategies should be used regularly and in combination to increase children's exposure to various forms of vegetables to encourage healthy eating habits at an early age and to promote an increased intake.

The decrease in the ED associated with incorporating vegetables in entrées can also lead to reductions in children's energy intake. In a single-meal study, reducing the ED of the entrée by 25% (by adding puréed vegetables and substituting low-fat versions of high-fat ingredients) decreased the meal energy intake by 17% (16). In a longer study, the ED of foods and beverages consumed over 2 consecutive days was reduced 27% (by increasing fruit and vegetable contents and decreasing fat and sugar contents), which resulted in a 14% decrease in the daily energy intake (17). The current study showed that, by incorporating vegetables into entrées as the sole method of reducing the ED, a 25% reduction in the entrée ED led to an 11% reduction in the daily energy intake. Although children were provided with multiple opportunities over the day to compensate for reductions in energy intakes, their daily energy intake decreased as the entrée ED was decreased. It is possible that it may take up to several days for energy compensation to occur; therefore, longer-term studies are needed of the effects of this strategy on energy intakes.

A parallel study was recently conducted in adults, in which the ED of entrées served over a day was reduced by 15% and 25% through the incorporation of vegetables (31). Similar to the present study, the adults ate a consistent weight of food so that the reduction in ED led to a significant increase in the vegetable consumption and a decrease in the energy intake. In addition, liking of the various vegetables could be assessed in more detail in this adult population. It was shown that the adults’ dislike of the vegetables that were incorporated into the entrées did not affect the consumption of the vegetable-enhanced entrées. This indicates that the incorporation of puréed vegetables into entrées increased the intake of vegetables even when the added vegetable was disliked. Because a dislike for the taste or texture of a vegetable is a substantial barrier to meeting recommended vegetable intakes, the incorporation of puréed vegetables into foods may be a key to overcome this barrier and increase vegetable intakes in children and adults.

A strength of the current study was that intakes were measured over a day rather than at a single meal. In addition, unmanipulated foods were provided at each meal and at several snacking occasions to allow children to compensate for energy deficits throughout the day. It is possible that children consumed foods in the evening other than the snacks provided, although this would likely account for only a small proportion of the daily intake. A limitation of the current study is that the findings may not be generalizable to all children. Children in the study were mostly white and had parents who were highly educated and had above-average incomes. Future work should include children from a more diverse population.

In conclusion, the covert incorporation of vegetables into foods can increase children's vegetable intake while decreasing energy intake. Nearly all children can benefit from an increase in vegetable intake; however, this strategy may be particularly advantageous for children who are overweight or obese and may benefit from a reduction in energy intake. To our knowledge, the long-term effects on the energy intake of incorporating vegetables into entrées served to children of all weight classes are unknown, and studies are needed to assess this. The covert incorporation of vegetables into foods is a simple technique that can be implemented in institutions, such as in daycare centers, schools, and hospitals, as well as in homes. Vegetables can be puréed, or to save time, puréed vegetables can be purchased and incorporated into recipes. Caregivers can adjust amounts of vegetables to meet their children's needs and can decide whether or not to inform the children that vegetables are used as an ingredient. Combined with other techniques, such as a repeated exposure to vegetables and the serving of large portions of well-liked vegetables, the covert incorporation of vegetables into foods has the potential to have a significant impact on the number of children who meet their recommended intake of vegetables.

Acknowledgments

We thank the students and staff of the Laboratory for the Study of Human Ingestive Behavior, the Center for Childhood Obesity Research, the Bennett Family Center, and the Child Development Laboratory at The Pennsylvania State University.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—MKS: design of the experiment, collection and analysis of data, and writing of the manuscript; and LSR, LLB, and BJR: design of the experiment and writing of the manuscript. None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Most Americans eat much less than recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106:1371–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Subar AF, Cleveland L, Friday J, Kahle LL. Fruit and vegetable intakes of children and adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1996;150:81–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox MK, Pac S, Devaney B, Jankowski L. Feeding infants and toddlers study: what foods are infants and toddlers eating? J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:s22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mennella JA, Ziegler P, Briefel R, Novak T. Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study: the types of foods fed to Hispanic infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106:S96–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annu Rev Nutr 1999;19:41–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicklaus S, Boggio V, Issanchou S. Food choices at lunch during the third year of life: high selection of animal and starchy foods but avoidance of vegetables. Acta Paediatr 2005;94:943–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasson C, Chapman K, James E. Fruit and vegetables should be targeted separately in health promotion programmes: differences in consumption levels, barriers, knowledge and stages of readiness for change. Public Health Nutr 2010;14:694–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeinstra GG, Koelen MA, Kok FJ, de Graaf C. Cognitive development and children's perceptions of fruit and vegetables; a qualitative study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007;4:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spill MK, Birch LL, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Eating vegetables first: the use of portion size to increase vegetable intake in preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:1237–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spill MK, Birch LL, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Serving large portions of vegetable soup at the start of a meal affected children's energy and vegetable intakes. Appetite 2011;57:213–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell EA, Castellanos VH, Pelkman CL, Thorwart ML, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake in normal-weight women. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:412–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell EA, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake across multiple levels of fat content in lean and obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:1010–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stubbs RJ, Johnstone AM, O'Reilly LM, Barton K, Reid C. The effect of covertly manipulating the energy density of mixed diets on ad libitum food intake in 'pseudo free-living’ humans. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998;22:980–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher JO, Arreola A, Birch LL, Rolls BJ. Portion size effects on daily energy intake in low-income Hispanic and African American children and their mothers. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1709–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leahy KE, Birch LL, Rolls BJ. Reducing the energy density of an entree decreases children's energy intake at lunch. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108:41–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leahy KE, Birch LL, Fisher JO, Rolls BJ. Reductions in entree energy density increase children's vegetable intake and reduce energy intake. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1559–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leahy KE, Birch LL, Rolls BJ. Reducing the energy density of multiple meals decreases the energy intake of preschool-age children. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:1459–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United States Department of Agriculture MyPyramid for preschoolers. Available from: http://www.mypyramid.gov/preschoolers/index.html (cited 28 February 2011)

- 19.US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Nutrition standards and menu planning approaches for lunches and requirements for afterschool snacks. Available from: http://cfr.vlex.com/vid/menu-approaches-lunches-afterschool-snacks-19903579 (cited 28 February 2011)

- 20.United States Department of Agriculture USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Available from: http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/. (cited 28 February 2011)

- 21.Birch LL. Dimensions of preschool children's food preferences. J Nutr Educ 1979;11:91–5 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birch LL. Preschool children's food preferences and consumption patterns. J Nutr Educ 1979;11:189–92 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birch LL. Effects of peer models’ food choices and eating behaviors on preschoolers’ food preferences. Child Dev 1980;51:489–96 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention A SAS program for the CDC growth charts. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/sas.htm (cited 17 November 2010)

- 25.Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Seymour JD, Tohill BC, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density determined by eight calculation methods in a nationally representative United States population. J Nutr 2005;135:273–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for mixed models. 2nd ed Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kral TV, Kabay AC, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Effects of doubling the portion size of fruit and vegetable side dishes on children's intake at a meal. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:521–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birch LL, McPhee L, Shoba BC, Pirok E, Steinberg L. What kind of exposure reduces children's food neophobia? Looking vs. tasting. Appetite 1987;9:171–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan SA, Birch LL. Infant dietary experience and acceptance of solid foods. Pediatrics 1994;93:271–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birch LL, Marlin DW. I don't like it; I never tried it: effects of exposure on two-year-old children's food preferences. Appetite 1982;3:353–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blatt AD, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Hidden vegetables: an effective strategy to reduce energy intake and increase vegetable intake in adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:756–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]