Abstract

Rationale

Skeletal myoblasts (SMs) with inherent myogenic properties are better candidates for reprogramming to pluripotency.

Objective

To reprogram SMs to pluripotency and show that reprogrammed SMs (SiPs) express embryonic gene and microRNA profiles and transplantation of predifferentiated cardiac progenitors reduce tumor formation.

Methods and Results

The pMXs vector containing mouse cDNAs for Yamanaka’s quartet of stemness factors were used for transduction of SMs purified from male Oct4-GFP+ transgenic mouse. Three weeks later, GFP+ colonies of SiPS were isolated and propagated in vitro. SiPS were positive for alkaline phosphatase, expressed SSEA1 and displayed a panel of embryonic stem (ES) cell specific pluripotency markers. Embryoid body formation yielded beating cardiomyocyte-like cells which expressed early and late cardiac specific markers. SiPS also had embryonic microRNA profile which was altered during their cardiomyogenic differentiation. Noticeable abrogation of let-7 family and significant upregulation of miR-200a–c and miR-290 to 295 was observed in SiPS and SiPS derived cardiomyocytes respectively. In vivo studies in an experimental model of acute myocardial infarction showed extensive survival of SiPS and SiPS derived cardiomyocytes in mouse heart after transplantation. Our results from 4-week studies in DMEM without cells (group-1), SMs (group-2), SiPS (group-3) and SiPS derived cardiomyocytes (group-4) showed extensive myogenic integration of the transplanted cells in group-4 with attenuated infarct size and improved cardiac function without tumorgenesis.

Conclusions

Successful reprogramming was achieved in SMs with ES cell-like microRNA profile. Given the tumorgenic nature of SiPS, their pre-differentiation into cardiomyocytes would be important for tumor-free cardiogenesis in the heart.

Keywords: heart, infarction, iPS cells, pluripotent, tumor formation, reprogramming, predifferentiation

Introduction

Cardiac regeneration using cell based therapy is faced with the dilemma of identifying the ideal type of cells for transplantation into the infarcted heart. Besides sub-optimal protocols of cell culture and transplantation, ease and availability of cells in sufficient number, their survival in the infarcted region and differentiation into morpho-functional cardiomyocytes for regeneration are some of the major challenges facing the heart stem cell therapy. Despite progress to clinical application, the use of stem cells has not been without controversies regarding their differentiation potential and ability to integrate with the host myocardium.1–4 Embryonic stem (ES) cells are the prototypical stem cells which unarguably possess near-ideal characteristics in terms of clonality, self-renewal and multipotentiality.5 However, moral and ethical issues regarding availability and immunological concerns have hampered their progress to clinical use.

The reprogramming of somatic cells with four stemness factors, called induced pluirpotent stem cells (iPS cells), has generated alternative source of stem cells which possess characteristics reminiscent of ES cells in terms of cell biology and pluripotent differentiation characteristics albeit with availability in large numbers without ethical issues and having better immunological behavior.6 Although the main focus of the current research in iPS cell technology pertains to refinement of the protocols to enhance the efficiency of reprogramming and to circumvent the safety issues for their human use,7 there are few studies which have shown their regenerative potential in vivo in general and for the infarcted myocardium in particular. Terzic’s group has taken the lead in this regard to show the reparability of mouse fibroblast derived iPS cells in an immunocompetent mouse heart model of acute myocardial infarction.8 The authors have demonstrated that the transplanted undifferentiated iPS cells survived in the infarcted myocardium and by four weeks, global heart function was recovered better than basal DMEM injected control animals. The authors further reported no observation of teratomas in iPS cells treated animal hearts. We have successfully generated mouse skeletal myoblast (SM) derived iPS cells (SiPS) which expressed endogenous markers of stemness similar to mouse ES cells. We report that cardiomyocytes derived from the 10-day old spontaneously beating embryoid bodies (EBs) obtained from SiPS (SiPS-CM) provide an excellent donor cell source which significantly attenuated infarct size expansion and improved contractile heart function in an experimental mouse model of acute myocardial infarction. Moreover, contrary to previous claims8, we observed that SiPS transplanted in the infarcted heart of immunocompetent recipient were teratogenic.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of mouse SMs

For our animal experiments, we used the Oct4/GFP transgenic mouse strain (Jackson Laboratories, Maine, USA) with GFP tagged to the endogenous Oct3/4 gene promoter. For SMs isolation, we followed the standard protocols routinely used in our laboratory as described in Supplementary data.

Generation and maintenance of SiPS

Retroviral vectors encoding for Yamanaka’s quartet of pluripotentcy determining factors were purchased from Addgene Inc. USA (Addgene plasmid# 13367; #13366; #13370; #17220 from Takahashi et al.).6 SMs from Oct4/GFP mice were seeded at a density of 1×105 cells/well in a 6-well plate. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were transduced with infectious supernatants from the respective vectors encoding for Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc factors for 48-hours transduction. Subsequently, the cells were re-plated in a 10cm cell culture dish on mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and observed for development of SiPS clones until 3-weeks. The GFP+ SiPS clones with ES cell like morphology were mechanically incised, cultured on mouse feeder cells and expanded individually in ES cell culture medium for use in further experiments. For confirmation of pluripotency induction, SiPS were fixed with 3%paraformaldehyde, permeabilized and stained with anti-stage specific embryonic antigen-1 (SSEA-1) antibody. The primary antigen-antibody reaction was detected with goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor-568 conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Cell Signaling Tech, Danvers, MA). Nucleiwere visualized by 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) staining. The murine SiPS clone Raf1 was expanded on mitotically inactivated murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; 5×104 cells/cm2) as described in Supplementary data.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Isolation of total RNA, and their subsequent first-strand cDNA synthesis, wasperformed using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and an Omniscript Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), respectively, per the instructions of manufacturer and as described earlier.10 The primer sequences used are given in Supplementary Table-I.

Alkaline phosphatase staining and immunocytochemistry

Alkaline phosphatase staining was done as per manufacturer’s instruction using Alkaline Phosphatase Detection kit (Millipore SCR004).

The undifferentiated colonies of iPS and ES cells were immunostained for the expression of the stage-specific embryonic antigen-1 (SSEA-1), Oct3/4 and Sox2 as described in Supplementary data. The immunostained cells were observed and photographed with a microscope equipped for epifluorescence (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Teratoma formation and Karyotyping

Teratogenicity of SiPS was assessed in immunodeficient mice (n=3) as described in Supplementary data. Karyotyping was carried out with quinacrine-Hoechst staining at the Transgenic Facility of University of Kansas Medical Center, KS.

Spontaneous cardiac differentiation of SiPS

For differentiation into cardiomyocytes, SiPS were grown in suspension culture for 3-days in high glucose DMEM containing 15%FBS, 5mM Penicillin/Streptomycin and 5mM non-essential amino acids. After 3-days in suspension culture, rounded EBs were formed which were seeded on gelatin coated dishes and cultured for 10-days. Adherent spontaneously contracting colonies were mechanically dissected and dissociated into single cardiomyocytes for use in further experiments.

miR analysis of SiPS and SiPS-CM

Total RNA from SMs, SiPS and SiPS-CM were labeled with Cy3. Samples were hybridized to a mouse miRNA microarray (LC Science, Tx) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Ultra-structural studies

Ultra-structural studies were performed on the myocardial tissue samples as described in Supplementary data using JEOL transmission electron microscope.

Experimental animal model and SiPS engraftment

The present study conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1985) and protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Cincinnati.

A model of acute myocardial infarction was developed in allogenic young female 8–12-weeks old female C57BL/6J immunocompetent mice as described earlier.11 Briefly, the animals were anesthetized (Ketamine/Xylazine 0.05ml intraperitoneally), intubated and mechanically ventilated (Harvard Rodent Ventilator, Model-683). Minimally invasive thoracotomy was performed for permanent ligation of coronary artery with a Prolene #9-0 suture. Myocardial ischemia was confirmed by color change of left ventricular wall. The animals were grouped (n=12/group) for intramyocardial injection of 10 μL of basal DMEM without cells (group-1) or containing 3×105 SMs (group-2), SiPS (group-3) and SiPS-CMs (group-4). Additionally, young female transgenic Oct4/GFP (C57BL/6x129S4SV/jae) (n=4) animals were used for transplantation of SiPS in group-3 to ascertain whether the use of isogenic recipient could curtail tumorgenic potential of SiPS. The cells were injected 10-minutes after coronary artery ligation at multiple sites (3–4 sites/heart) in the free wall of the LV under direct vision. For post-engraftment tracking of the transplanted cells and determination of their fate, the cells were labeled with Q-tracker®-625 (red fluorescence; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The chest was closed and the animals were allowed to recover. Subsequently, the animals were injected Buprinex (0.05ml subcutaneously) during the first 24-hours to alleviate pain and were maintained until 4-weeks before euthanasia and recovery of the heart tissue samples.

Transthoracic echocardiography

The animals (n=8 in groups 1,2,3 each and n=11 in group 4) were anesthetized and transthoracic echocardiography was performed as detailed in supplementary data.

Histological and immunohistological studies

The animals were euthanized at 7-days and 4-weeks after heart function studies. The heart tissue samples were removed and used for histological and immunohistological studies as described earlier.12

Results

Overexpression of stemness factors and SMs reprogramming

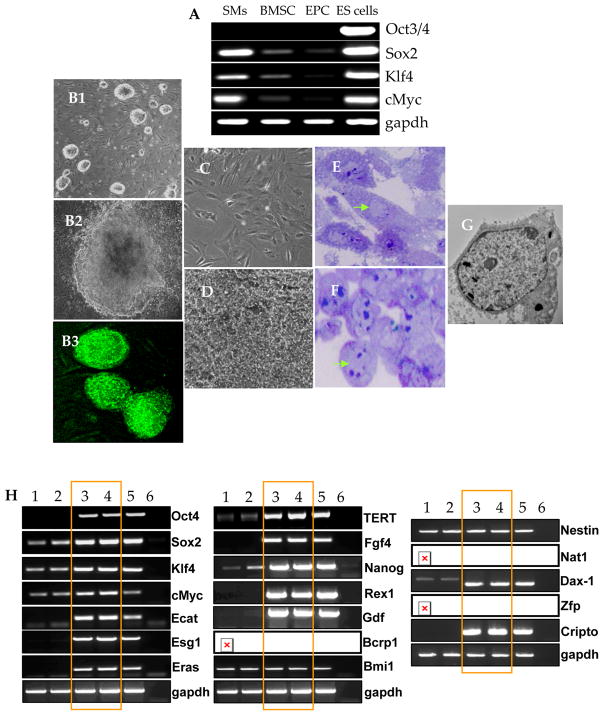

The SMs were characterized for purity by flow cytometry for desmin expression (Supplementary Figure IIA-B) and by immunocytochemistry for desmin and vimentin expression (Supplementary Figure II-D) and RT-PCR for MyoD and vimentin expression (Supplementary Figure IIE). We successfully reprogrammed NatSMs to achieve pluripotency subsequent to overexpression of four stemness factors Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-Myc (Figure-1A, B1–B3). Culture of the undifferentiated SiPS on MEFs or on gelatin coated dishes without feeder cells exhibited a typical ES-like cell morphology which appeared as compact, opaque round clusters with well-defined margins in the undifferentiated state and expressed Oct3/4 promoter driven GFP (Figure-1 B1–B3). On the other hand, the non-reprogrammed NatSMs with elongated spindle shape retained their morphological characteristics in culture for 20-days and did not express Oct3/4 promoter driven GFP which indicated their non-transformed status (Figure 1C–D). Sub-cellular characteristics included a large nucleus/cytoplasmic ratio and scanty cytoplasmic contents in SiPS as compared to the NatSMs (Figure 1E–G). Unlike NatSMs, SiPS endogenously overexpressed Oct4, Sox2, cMyc, Klf4 and Nanog besides a panel of other pluripotency gene markers (Figure-1H; lanes 3–4) which was comparable with mouse ES cells (Figure-1H; lane-5). RT-PCR was performed to observe changes in exogenous and endogenous gene expression of stemness factors in SMs and SiPS (Supplementary Figure-III). Fluorescence immunostaining revealed that reprogramming induced strong positive expression of the undifferentiated ES cell markers including SSEA-1 and higher alkaline phosphatase which were absent in NatSMs (Supplementary Figure IA–B). Karyotyping revealed that more than 85% of the cells were euploid and without any chromosomal abnormalities indicating that the clones used in the study possessed normal genetic makeup. Subcutaneous injection of SiPS formed teratomas in all the 3 immunodeficient hosts which showed typical three germ layer characteristics (Supplementary Figure-IC).

Figure 1. Reprogramming of mouse SMs using 4-factor transduction protocol.

(A) RT-PCR showing endogenous expression of Sox2, Klf4 and cMyc in NatSMs. (B1–B3) Typical ES cell like morphology was observed in SiPS clone 3 weeks after transduction with retroviral vectors encoding for Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and cMyc. B1 and B2 are phase contrast images whereas B3 shows Oct4/GFP expressing SiPS. (C–D) NatSMs retained their spindle shaped morphology in culture for 20-days and did not express Oct4 driven GFP which showed their non-transformed status. (E–F) Semi-thick sections (1μm) of (E) non-transformed NatSMs and (F) SiPS stained with toluidine blue. Note the typical elongated spindle like structure of NatSMs with small nucleus in comparison with SiPS with rounded morphology, very large nucleus typical of ES cells and scattered patches of condensed chromatin. (G) Transmission electron micrograph of a typical SiPS showing large nucleus to cytoplasm ratio characteristic of ES cells (original magnifications: B1=20×; B2=60×; B3=40×; C–D20×; E–F=60×). (H) RT-PCR of ES cell specific marker genes and pluripotency transgenes in mouse SiPS. GAPDH was used as a loading control whereas blank well amplified without the reverse transcriptase was used as a negative control (lane-6). Other lanes include, lanes 1–2=SMs; lane-3=RAR1 SiPS clone; lane-4=RAR1 SiPS clone; lane-5=ESCs.

In vitro predifferentiation of cardiac progenitors from SiPS for transplantation

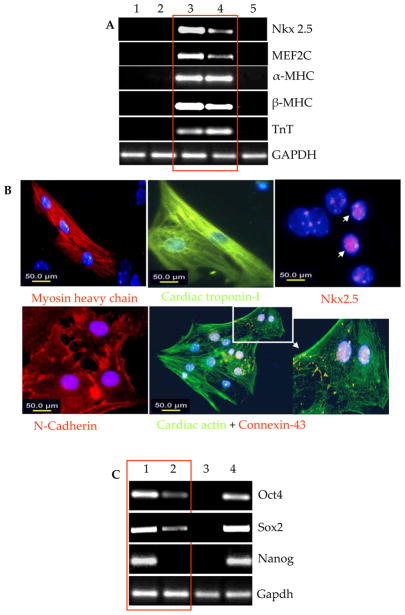

Of the two murine SiPS clones, i.e., Raf1 and Raf2, characterized in vitro for pluripotency, Raf1 was differentiated by a standard EB-based differentiation protocol. Between days 3–5 in differentiation culture medium, the floating EBs were transferred to adherent culture conditions where the cells were cultured for 5–6 days. By day-10 after initiation of differentiation, few spontaneously beating areas were observed which continued to increase and expand with longer time maintenance of the culture (Supplementary data Movie-I). Such synchronous contractile activity in SiPS-CMs was observed for up to 3–4 weeks. Profiling of cardiac specific genes was performed for characterization of the spontaneously beating EBs (Figure-2). We observed multi-fold increase in cardiac specific genes expression in 10-day old beating EBs including maturation markers α-MHC, β-MHC and cardiac troponin-I in comparison with SiPS and NatSMs (Figure-2A and Supplementary Figure-IV). Mouse heart was used as a positive control. The cardiac specific molecular changes during differentiation of SiPS were confirmed by fluorescence immunostaining of SiPS and SiPS-CMs (Figure-2B). A higher propensity of SiPS-CMs positive for Nkx2.5, myosin heavy chain, cardiac troponin-I, cardiac actin, and gap-junction proteins N-cadherin and connexin-43. Incidentally, the level of pluripotency markers Oct3/4, Sox2 and Nanog concomitantly declined in SiPS during differentiation to become SiPS-CMs (Figure-2C, Supplementary Figure-V). RT-PCR was also performed to observe gene expression changes in endogenous and exogenous Oct3/4 and Sox2 in SiPS-CMs in comparison to SiPS (Supplementary Figure-VI).

Figure 2. Spontaneous cardiomyogenic differentiation of SiPS.

(A) RT-PCR for cardiomyocyte specific gene expression changes in SiPS-CM which developed by spontaneous differentiation of SiPS on day-10 after EBs formation (lane-3) in comparison with NatSMs (lane-1), undifferentiated SiPS (lane-2) and ES cells (lane-5). The heart was used as a positive control (lane-4). (B) Fluorescence immunostaining of SiPS-CM from a single beating cluster for detection of cardiac specific marker proteins including myosin heavy chain (red), cardiac troponin-I (green), Nkx2.5 (red), N-Cadherin (red), Cardiac actin (green) and Cx-43 (red). DAPI staining was used for visualization of nuclei (original magnification=100×). (C) RT-PCR for pluripotency gene expression in SiPS-CM showed down-regulation of Oct3/4, Sox2, and Nanog with the appearance cardiac specific markers as shown in Figure-2C (lane-1=SiPS; lane-2=SiPS-CM; lane-3=heart (positive control); 4=ES cells.

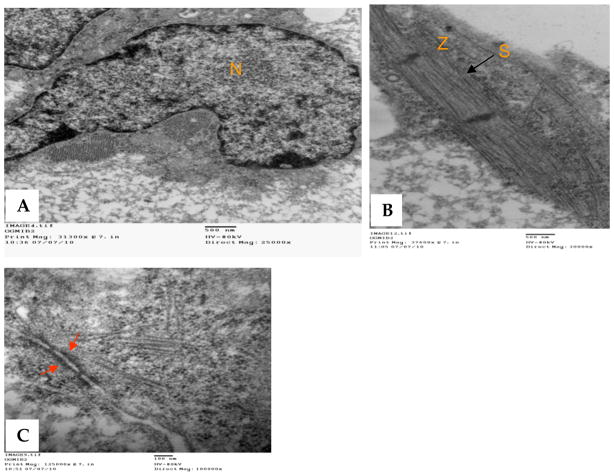

Transmission electron microscopy revealed ultrastructural features of the developing cardiomyocytes in SiPS-CMs with fully developed sarcomeres and ribosomes (Figure 3A–C). Tight junctions between adjacent SiPS-CMs were also observed in the spontaneous beating regions in the culture (indicated by red arrows; Figure-3C)

Figure 3. Ultra-structure studies of SiPS-CM in vitro.

(A–B) Transmission electron micrographs of SiPS-CMs showing typical striated structure with sarcomeric organization (S) and z-lines. (C) Tight junctions were observed between adjacent SiPS-CMs (indicated by red arrows). (bar: A&B=500nm; C=100nm).

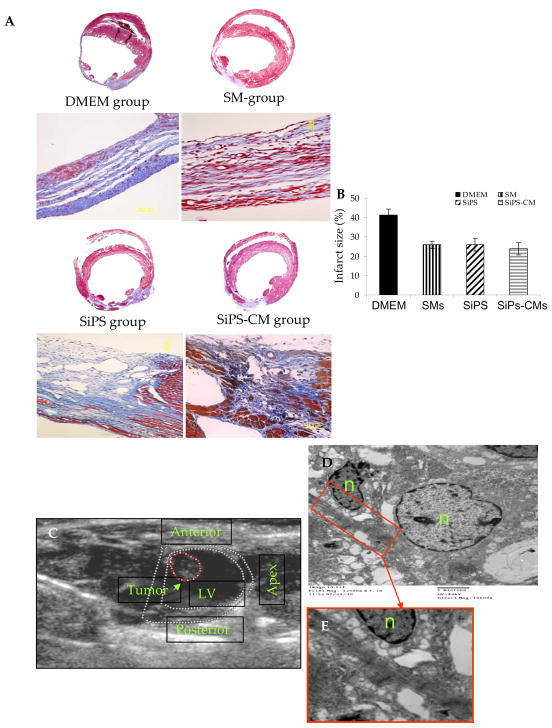

Prevention/reduction of tumorgenicity by predifferentiated cardiac progenitors

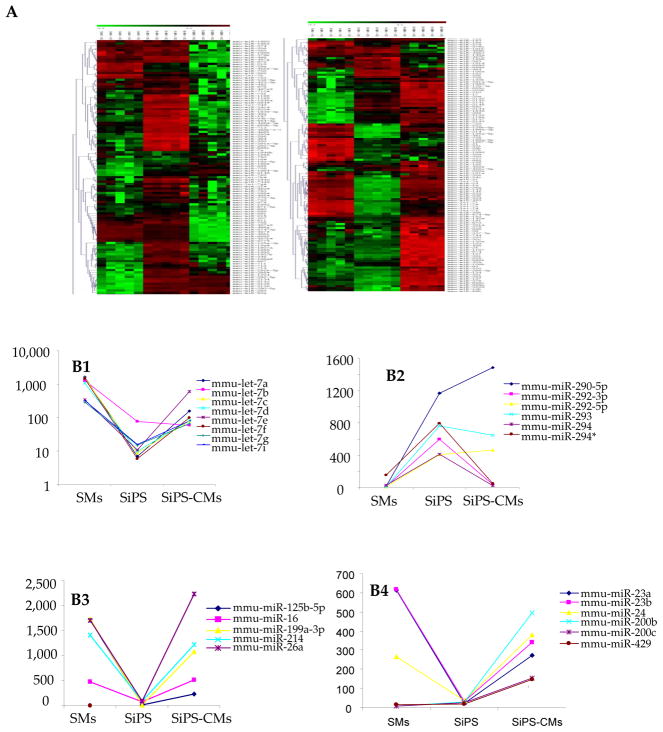

As published in our first report on teratogenicity of SiPS where 6 of the 16 SiPS transplanted animals developed cardiac tumors13, no tumor formation was observed in any other group included in present study. Figure-5C is a representative echocardiograph of an animal heart which developed cardiac tumor in the LV 4-weeks after SiPS transplantation. Histological studies confirmed that these tumors consisted of cells from the three germ layers13. Transmission electron microscopy revealed regions with myogenic differentiation identified on the basis of their typical striated muscle fiber-like structure with sarcomeric organization (Figure-5D). Moreover comparative miRNA profile revealed that cardiomyocytes isolated from SiPS expressed tumor suppressive miRs 125b, 16, 199a, 214, 26a, 200b and 200c in abundance when compared to SiPS (Figure-4). These results suggest that directed differentiation of iPS cells prior to transplantation is highly desirable to prevent tumor formation.

Figure 5. SiPS-CMs transplantation reduced infarction size.

(A–B) Masson’s trichrome staining of the histological sections from various treatment groups of animals showing significantly reduced infarction size in the cell transplanted animal hearts as compared to DMEM treated controls. (C) Echocardiogram of a rat heart showing tumor in the LV cavity in one of the animal 4-weeks after transplantation of SiPS. (D) Transmission electron micrograph showing myogenic differentiation (identified by striated sarcomeric structures with clear z-bands) in the tumor seen in Figure-5C. Figure-5E is the magnified image of the boxed area (red) in Figure-5D (original magnification= 12500×).

Figure 4. Relative miR expression profile during reprogramming of SMs to form SiPS and their subsequent differentiation into SiPS-CMs.

(A) Heat map showing miR expression profiling in SMs, SiPS and SiPS-CMs. Green in the heat map shows miRs which were down-regulated in the sample and the red shows miRs that were up-regulated in the samples. (B1, B2) The miR expression profiles of let7 family and 290 cluster miRs which are known for their role in reprogramming and differentiation of stem cells as observed in NatSMs, SiPS and SiPS-CMs. (B3) Upregulation of tumor supressive miRs as observed in SiPS-CMs. (B4) Other significantly regulated miRs with diverse functions.

Histological benefits of SiPS and their derivatives

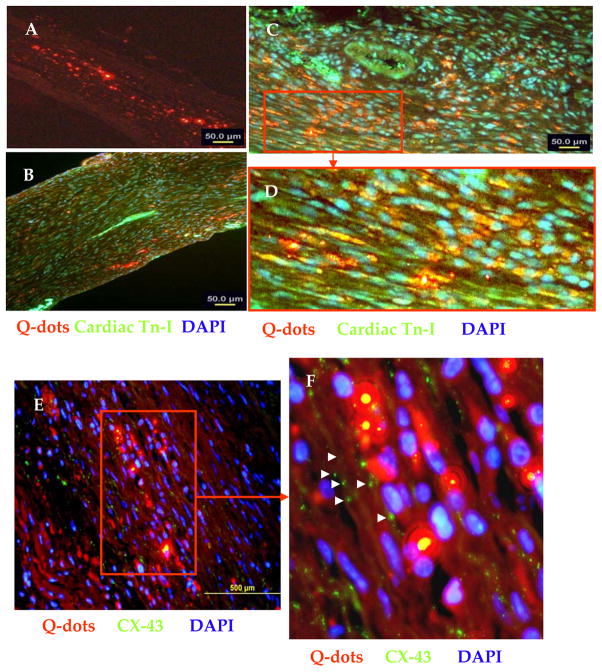

Histochemical studies on the animal hearts from various treatment groups (n=4/group), 4-weeks after their respective treatment, were performed on at least two middle slices of the heart. We observed extensive myocyte damage in the LV which was replaced by scar tissue and thinning of the LV wall was reduced in all the treatment groups (Figure-5). However, all the cell treatment groups had significantly attenuated infarct size as compared to DMEM injected controls (41.3±1.3%). However, infarct size between cell treatment groups did not show significant difference despite the fact that SiPS-CMs treated animal hearts had the smallest infarct size (23.9±3.1%) as compared to SMs (25.9±1.8) and SiPS treated (26±3.3). Architectural analysis of hematoxylin-eosin stained cardiac tissues had extensive presence of islands of myofibers in the infarcted hearts of the cell treated groups (Figure-5). Four weeks after cell transplantation, Q-dot labeled cells were observed in the infarct and peri-infarct areas in the LV (Figure-6A). Immunohistochemistry for cardiac troponin-I and Cx-43 was performed to determine the fate and integration of the transplanted cells in the heart. Co-localization of Q-dots (red fluorescence) with cardiac troponin-I (green fluorescence) in the infarct and peri-infarct regions in the SiPS-CMs transplanted animal hearts indicated their myogenic differentiation (Figure 6B–D) which formed gap junctions with the host myocytes (Figure 6E–F).

Figure 6. Immunohistological evidence that transplanted SiPS-CMs adopted cardiomyogenic fate in vivo.

(A) Epifluorescence observation of the histological section showing extensive presence of the transplanted SiPS-CMs in the infarcted myocardium (indicated by red fluorescence) 4-weeks after transplantation. (B) Immunostaining of the histological sections from SiPS-CM transplanted animal heart for cardiac actin expression (green fluorescence) which co-localized with red fluorescence to show myogenic differentiation of the transplanted cells. Figure-6D represents the magnified image of an area selected in Figure-6C (red box) to show co-localization of red and green fluorescence. (E–F) Fluorescence immunostaining of histological sections for Cx-43 expression (green fluorescence) to show integration of SiPS-CM (red fluorescence) in the centre of the infarct. (Original magnifications: A=10×; B= 20×; C=40×).

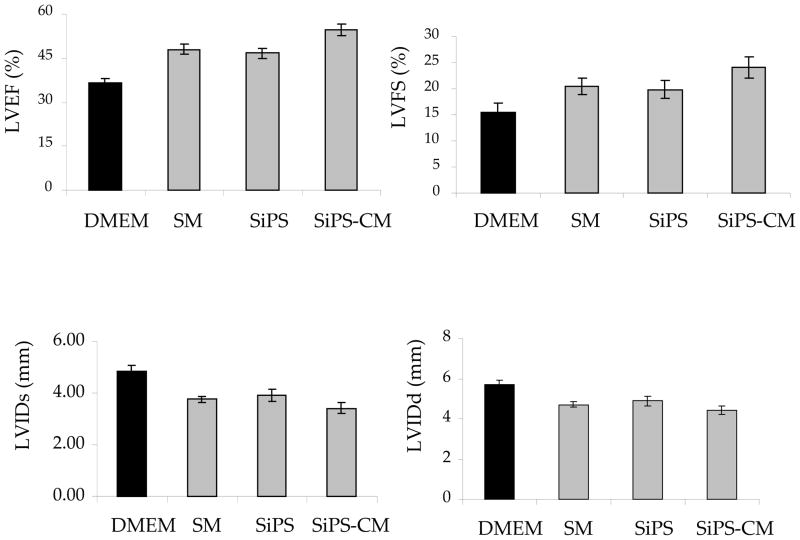

Heart Function studies

Permanent LAD coronary artery ligation led to significant deterioration in the indices of LV contractile function including LVEF and LVFS as compared to the baseline values (n=4; 74.2±2.6; 36.7±2.2% respectively). Transplantation of NatSMs, SiPS and SiPS-CMs significantly preserved the global pump function of the infarcted myocardium (Figure-7). In comparison with the DMEM treated controls (36.3±1.5%; 15.35±1 p<0.001), LVEF and LVFS were significantly higher in NatSMs transplanted animal hearts (48.04±1.5%; 20.4±1.6), SiPS transplanted hearts (46.7±1.7; 19.9±1.3) and SiPS-CMs transplanted hearts (54.7± 2; 24.1±2) respectively. Inter group analysis showed that in comparison with DMEM treatment, both LVEF and LVFS significantly improved in cell transplanted groups (DMEM vs cell transplanted groups p<0.05). However, LVEF and LVFS showed significant improvement in SiPS-CMs treated group compared to other cell transplanted hearts. The pathological remodeling of LV in the cell transplanted groups was also significantly reduced as shown by LV chamber dimensions during systole (LVDs) and diastole (LVDd). In comparison with the chamber dimensions during systole (4.4±0.2) and diastole (5.69±0.3) in DMEM treated group, both LVDs and LVDd were significantly preserved following intervention with NatSMs (3.7±0.1 and 4.7±0.1), SiPS (3.9± 0.2 and 4.9±0.24) and SiPS-CMs (3.4±0.2 and 4.4±0.1) respectively.

Figure 7. SiPS-CM transplantation better preserved the cardiac function.

(A–B) Whereas LVEF and LVFS were significantly deteriorated in DMEM injected control animal hearts, cell therapy, irrespective of the type of the cell injected, preserved the contractile function of the heart (p<0.05 vs DMEM injected control). However, significant improvement in LVES and LVFS was observed in SiPS-CM treatment group. Similarly, LV chamber dimensions during diastole and systole were better preserved in the cell transplanted animal hearts as compared to the controls thus indicating prevention of pathological remodeling.

Discussion

The breakthrough discovery that somatic cells could be reprogrammed to pluripotent status has generated immense interest in pluripotent stem cells due to their vast therapeutic applications. Thus, the prospect of using iPS cells has added new dimensions to stem cell based therapy. We report reprogramming of mouse SMs and their application for cardiac repair following myocardial infarction in comparison with SiPs and NatSMs. Our results avidly showed the superiority of allogenic SiPS-CMs in terms of safety and regenerative capacity in an immunocompetent mouse model of acute myocardial infarction. The major findings of the study are: 1- SMs can be easily reprogrammed to develop iPS cells 2- Undifferentiated iPS cells are tumorgenic in immunocompetent hosts 3- directed differentiation of iPS cells to derive cardiac progenitors circumvent their tumorgenicity following transplantation in immunocompetent recipients. 4- Moreover, we provide a comparative miR expression profile in NatSMs, SiPS and SiPS-CMs which essentially determined the pluripotent status of SiPS during reprogramming of SMs and showed an upregulated expression of tumor suppressive miRs in differentiated cardiac cells.

The rationale to reprogram SMs was based on our results that SMs endogenously expressed three (i.e., Sox2, cMyc and Klf4) of the Yamanaka’s quartet of transcription factors required for reprogramming6, thus making these cells an easier choice for reprogramming as compared to the terminally differentiated fibroblasts. It is highly likely that reprogramming SMs would require fewer factors.14 Secondly, it is anticipated that iPS cells carry forward the epigenetic memory of the somatic cells of their origin.15 Therefore, SMs which posses inherent myogenic potential, would be a better choice for reprogramming than the non-myogenic fibroblasts. Despite the presence of three of the four required stemness factors, the use of Oct4 alone did not induce pluripotency in SMs. It appears that there is an optimum threshold level of expression for of each of these factors that is required to ensure reprogramming of SMs. A recent study has shown that SMs can be reprogrammed using Yamanaka’s quartet of stemness factors with simultaneous suppression of MyoD in the reprogrammed cells which substantiate our results15. However, the authors did not show their cardiac differentiation capability in vitro as well as in experimental animal model. In an interesting study, neurospheres were obtained from mouse iPS cell lines derived from embryonic fibroblasts, adult tail-tip fibroblasts, hepatocytes, and stomach epithelial cells16 and evaluated the teratogenicity of the secondary neurospheres. Interestingly, iPS cells of different tissue origins differed in their teratogenicity which also correlated well with the presence of undifferentiated iPS cells in the neurospheres. These data support our notion that certain somatic cell types may be superior choice for reprogramming and would also influence the subsequent differentiation potential of their derived iPS cells. Another important consideration in the selection of SMs for reprogramming was that the choice of cell may impact the tumorgenicity of their derived iPS cells. Moreover, SMs have been extensively studied for myocardial repair in both experimental animal models and human patients.17,18 However, their lack of functional integration post-engraftment in the heart and the issues of arrhythmogenicity have marred their clinical applicability.19 We believe that reprogrammed SMs would provide an excellent autologous source of cells for transplantation.

Since inception of the iPS cell technology, in vivo cardiomyogenic potential of iPS cells has been mostly studied after their blastocyst injection.20,21 The injected iPS cells differentiated into mature cardiomyocytes in the chimeric heart. These data were well supported by in vitro experimental studies which examined the cardiomyogenic potential of ES cells.20,22 Molecular studies demonstrated upregulation of mesodermal gene and protein markers of cardiac differentiation which was confirmed by fluorescence immunostaining and ultrastructural studies. Similar to ES cells, iPS cells can differentiate into functionally competent cardiomyocytes23, however, very few studies showed that iPS cells regenerated the infarcted myocardium after transplantation. Terzic et al., have reported improved global cardiac function in iPS cell treated mice, however, without substantiating cardiogenesis in the infarcted mice heart with immunohistological evidence.8 Given the tumorgenic nature of pluripotent stem cells, it is important to ensure that the transplantation of SiPS is free of undifferentiated cells24 which are potential contributors of tumorgenicity of iPS cells16. Even the use of isogenic animals for transplantation of SiPS failed to curtail their teratogenic characteristics in the heart. Isolation of specific subtypes of SiPS with no oncogenic tendency will also help to curtail tumorgenicity of SiPS.

In view of difficulties in using iPS cell based cell therapy we hypothesized that pre-differentiation or guided differentiation of SiPS would be safer and effective approach for transplantation. We therefore opted to transplant 8–10 days old EBs which contained developing and beating myocytes. We observed increased myogenesis in SiPS-CMs transplanted hearts and more importantly, without incidence of tumor formation as against significantly higher number of animals (n=4) developing tumors in SiPS transplanted hearts. As the number of cells transplanted in group-3 and group-4 were similar, therefore contribution of residual SiPS population towards improved cardiac function would be marginal. Strategies to enhance the purity of SiPS-CMs and to exclude the presence of undifferentiated SiPS are therefore warranted. Directed differentiation protocols will require optimal pretreatment of SiPS with specific cytokines, growth factors and/or small molecules rather than the use of spontaneous differentiation which may lack reproducibility.

Our study provides the first ever miR expression profiling of SMs during the process of reprogramming and differentiation. miRs are global regulators of stem cell functions including their differentiation capacity.25 Significant changes were noticed in the expression pattern of miR let-7, miR-200 and miR-290 families that largely varied with the differentiation status of the cells. Upregulation of let-7 family of miRs is associated with differentiation status rather than type of the cell.26 We observed that let family of miRs including let7 a–g, i, and miR-98 were down-regulated in SiPS as compared to NatSMs. Nevertheless, there was an obvious increase in their expression during myogenic differentiation of SiPS. The five member miR-200 family (miR-200a–c, miR-141 and miR-429) also showed similar trend. Of these members, miR-200a–c were not detected in either NatSMs or SiPS, however their expression increased in SiPS-CMs which indicated that incomplete differentiation status of SMs.26 Besides these two important miR families, SiPS also expressed other signature ES cell miRs including miR-290, 292 and 293 that are not only regulated by pluripotency genes Oct4, Nanog and Sox2 but also target these genes in “incoherent feed-forward loops”. These data reflected similarity of miR expression profile between SiPS and ES cells. Similarly, some other miRs with significantly altered expression during transition of SMs to SiPS and then onward differentiation into cardiomyocytes included miR-23a and 23b (regulated by cMyc)27, miR-214 (part of regulatory circuit controlling differentiation and cell fate decision)28 and miR-21, a known suppressor of Nanog, Sox2 and Oct425, showed substantial increase following cardiomyogenic differentiation of SiPS. miR-24 a ubiquitously expressed miRNA has an anti-proliferative effect independent of p53 function29 was inhibited in SiPS as compared to SMs and SiPS-CMs. Moreover, miR-26a is a muscle specific miR which is upregulated during myogenesis30 was up-regulated both in SMs and in SiPS-CMs in comparison with the SiPS. Let-7, miR-125b, miR-16, miR-199a, miR-214, miR-26a, miR-200b and miR-200c are among the tumor suppressive miRs that are significantly up regulated in SiPS-CM31,32,333. All these data clearly reflect not only the similarity between miR expression profile of ES cells and SiPS during reprogramming of SMs but also highlights up regulation of tumor suppressive miRs in SiPS-CMs as compared to SiPS.

In conclusion, the study results signify SMs as better candidates for reprogramming to pluripotency due to their inherent expression of three of the four stemness determining factors. Although the study used conventional retroviral vector based ectopic expression of four stemness factors, intrinsic expression of three of the required four stemness factors raises the possibility of their reprogramming with smaller number of factors or even by treatment with non-viral methods for clinical applications. Transplantation of cardiac progenitors predifferentiated from SiPS was optimal for tumor-free cardiogenesis with resultant structural and functional recovery in an immunocompetent animal model of acute myocardial infarction. Given that tumorgenesis is a time-dependent process, it would be prudent to carry out longer-term studies to assess tumorgenic potential of SiPS-CMs besides designing more systematic studies for guided differentiation of SiPS for transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is known?

Committed skeletal muscle progenitor cells (myoblasts) can be reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells that are similar to embryonic stem cells.

Skeletal myoblast derived induced pluripotent stem cells (SiPS) are potential candidates for the regeneration of ischemic myocardium.

SiPS transplanted into the ischemic myocardium have been reported to differentiate into cells of all 3 germ layers leading to tumor formation in the heart.

What new information this article contributed?

Pre-differentiation of SiPS into developing cardiomyocytes before transplantation is important for regeneration of infarcted myocardium with minimal risk of myocardial tumor formation.

Cardiac progenitors derived from SiPS are an excellent source of cells for cardiac regeneration. Transplantation of these cells was found to reduce infarct size and improve heart function in a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction.

In addition to known pluripotency related miRs like Let-7 family miRs and 290 cluster miRs, this study also reveals other miRs like 125b, 16, 199, 214, 26a and 200a/b, which are tumor suppressive miRs, are expressed in differentiated cardiomyocytes. These miRs can be used as tumorigenic biomarkers of iPS cells derived progenitors.

A major goal of cardiac stem cell research is to identify the ideal type of cell for cardiac regeneration. Skeletal myoblasts have been used in clinical trials involving cardiac ischemia, albeit myoblast transplantation is reported to cause arrhythmias. We have recently reported that myoblasts can be reprogrammed to induced pluripotent stem cells and their direct transplantation is associated with a high risk of tumor formation even in an immunocompetent host. In this study we differentiated myoblast derived IPS into cardiomyocytes (SiPS-CM) prior to transplantation to assess their potential to regenerate the infarcted myocardium. Our in vivo results in a mouse model of myocardial injury indicate that differentiation before transplantation reduces the risk of tumor formation while simultaneously improving heart function and reducing infarct size. Our results suggest that skeletal myoblasts may be better candidates for reprogramming using novel non-viral approaches as they show a modest expression of three of the four stemness genes at base line. By comparing the miRNA profile of committed myoblasts and cardiomyocytes with the miRNA profile of SiPS this study highlights the miRs that are specifically regulated under pluripotent state. These pluripotency-specific miRs are ideal candidates for non-viral miRNA reprogramming of differentiated cells. Moreover as pluripotency and tumorigenicity are closely regulated, this study could be helpful in identifying potential miRNA biomarkers for turmor free cardiac regeneration.

Acknowledgments

Source of Research Support

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants # R37-HL074272;HL080686;HL087246(M.A) and HL087288;HL089535(Kh.H.H).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- SMs

skeletal myoblasts

- ES

Embryonic stem

- iPS

induced pluirpotent stem

- SiPS

skeletal myoblast derived iPS cells

- EBs

embryoid bodies

- SiPS-CM

cardiomyocytes derived from the 10-day old spontaneously beating embryoid bodies obtained from SiPS

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- Oct4

octamer-binding transcription factor 4

- Sox2

sex determining region Y-box 2

- Klf4

Kruppel-like factor 4

- c-Myc

cellular-myelocytomatosis proto-oncoprotein gene

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- SSEA-1

anti-stage specific embryonic antigen-1antibody

- Cx-43

connexin 43

- MyoD

myogenic differentiation 1

- NatSMs

native skeletal myoblasts

- Q-dots

quantum dots

- LVDs

left ventricular chamber dimensions during systole

- LVDd

left ventricular chamber dimensions during diastole

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVFS

left ventricular fractional shortening

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

Nothing to disclose.

Bibliography

- 1.Nygren JM, Jovinge S, Breitbach M, Sawen P, Roll W, Hescheler J, Taneera J, Fleischmann BK, Jacobsen SE. Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells generate cardiomyocytes at a low frequency through cell fusion, but not transdifferentiation. Nat Med. 2004;10:494–501. doi: 10.1038/nm1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kajstura J, Rota M, Whang B, Cascapera S, Hosoda T, Bearzi C, Nurzynska D, Kasahara H, Zias E, Bonafe M, Nadal-Ginard B, Torella D, Nascimbene A, Quaini F, Urbanek K, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells differentiate in cardiac cell lineages after infarction independently of cell fusion. Circ Res. 2005;96:127–37. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000151843.79801.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leobon B, Garcin I, Menasche P, Vilquin JT, Audinat E, Charpak S. Myoblasts transplanted into rat infarcted myocardium are functionally isolated from their host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7808–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232447100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudo M, Wang Y, Wani MA, Xu M, Ayub A, Ashraf M. Implantation of bone marrow stem cells reduces the infarction and fibrosis in ischemic mouse heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1113–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singla DK. Embryonic stem cells in cardiac repair and regeneration. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1857–63. doi: 10.1089/ARS.2009.2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowry WE, Plath K. The many ways to make an iPS cell. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1246–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1108-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Yamada S, Perez-Terzic C, Ikeda Y, Terzic A. Repair of acute myocardial infarction by human stemness factors induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2009;120:408–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.865154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niagara MI, Haider H, Jiang S, Ashraf M. Pharmacologically preconditioned skeletal myoblasts are resistant to oxidative stress and promote angiomyogenesis via release of paracrine factors in the infarcted heart. Circ Res. 2007;100:545–55. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258460.41160.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu G, Haider HK, Jiang S, Ashraf M. Sca-1+ stem cell survival and engraftment in the infarcted heart: dual role for preconditioning-induced connexin-43. Circulation. 2009;119:2587–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai Y, Ashraf M, Zuo S, Uemura R, Dai YS, Wang Y, Haider H, Li T, Xu M. Mobilized bone marrow progenitor cells serve as donors of cytoprotective genes for cardiac repair. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:607–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang S, Haider H, Idris NM, Salim A, Ashraf M. Supportive interaction between cell survival signaling and angiocompetent factors enhances donor cell survival and promotes angiomyogenesis for cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2006;99:776–84. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000244687.97719.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed RP, Buccini S, Ashraf M, Haider KH. Cardiac tumorgenic potential of induced pluripotent stem cells in immunocompetent host with myocardial infarction. Regen Med. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.103. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JB, Zaehres H, Wu G, Gentile L, Ko K, Sebastiano V, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Ruau D, Han DW, Zenke M, Scholer HR. Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature. 2008;454:646–50. doi: 10.1038/nature07061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe S, Hirai H, Asakura Y, Tastad C, Verma M, Keller C, Dutton JR, Asakura A. Myod Gene Suppression By Oct4 is Required for Reprogramming in Myoblasts to Produce Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cells. doi: 10.1002/stem.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miura K, Okada Y, Aoi T, Okada A, Takahashi K, Okita K, Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Ogawa D, Ikeda E, Okano H, Yamanaka S. Variation in the safety of induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:743–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menasche P, Hagege AA, Scorsin M, Pouzet B, Desnos M, Duboc D, Schwartz K, Vilquin JT, Marolleau JP. Myoblast transplantation for heart failure. Lancet. 2001;357:279–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haider H, Ye L, Jiang S, Ge R, Law PK, Chua T, Wong P, Sim EK. Angiomyogenesis for cardiac repair using human myoblasts as carriers of human vascular endothelial growth factor. J Mol Med. 2004;82:539–49. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0546-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fouts K, Fernandes B, Mal N, Liu J, Laurita KR. Electrophysiological consequence of skeletal myoblast transplantation in normal and infarcted canine myocardium. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:452–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenke-Layland K, Rhodes KE, Angelis E, Butylkova Y, Heydarkhan-Hagvall S, Gekas C, Zhang R, Goldhaber JI, Mikkola HK, Plath K, MacLellan WR. Reprogrammed mouse fibroblasts differentiate into cells of the cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineages. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1537–46. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Fernandez A, Nelson TJ, Yamada S, Reyes S, Alekseev AE, Perez-Terzic C, Ikeda Y, Terzic A. iPS programmed without c-MYC yield proficient cardiogenesis for functional heart chimerism. Circ Res. 2009;105:648–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gai H, Leung EL, Costantino PD, Aguila JR, Nguyen DM, Fink LM, Ward DC, Ma Y. Generation and characterization of functional cardiomyocytes using induced pluripotent stem cells derived from human fibroblasts. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:1184–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mauritz C, Schwanke K, Reppel M, Neef S, Katsirntaki K, Maier LS, Nguemo F, Menke S, Haustein M, Hescheler J, Hasenfuss G, Martin U. Generation of functional murine cardiac myocytes from induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2008;118:507–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.778795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khryapenkova TG, Plotnikov EY, Korotetskaya MV, Sukhikh GT, Zorov DB. Heterogeneity of mitochondrial potential as a marker for isolation of pure cardiomyoblast population. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2008;146:506–11. doi: 10.1007/s10517-009-0327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gangaraju VK, Lin H. MicroRNAs: key regulators of stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:116–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peter ME. Let-7 and miR-200 microRNAs: guardians against pluripotency and cancer progression. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:843–52. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.6.7907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, Zeller KI, De Marzo AM, Van Eyk JE, Mendell JT, Dang CV. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juan AH, Sartorelli V. MicroRNA-214 and polycomb group proteins: A regulatory circuit controlling differentiation and cell fate decisions. Cell Cycle. 9 doi: 10.4161/cc.9.8.11472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra PJ, Song B, Wang Y, Humeniuk R, Banerjee D, Merlino G, Ju J, Bertino JR. MiR-24 tumor suppressor activity is regulated independent of p53 and through a target site polymorphism. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong CF, Tellam RL. MicroRNA-26a targets the histone methyltransferase Enhancer of Zeste homolog 2 during myogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9836–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee YS, Dutta A. The tumor suppressor microRNA let-7 represses the HMGA2 oncogene. Genes Dev. 2007;21(9):1025–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.1540407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott GK, Goga A, Bhaumik D, Berger CE, Sullivan CS, Benz CC. Coordinate suppression of ERBB2 and ERBB3 by enforced expression of micro-RNA miR-125a or miR-125b. J Biol Chem. 2007;12:282(2):1479–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Visone R, Croce CM. MiRNAs and cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(4):1131–8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.