Abstract

Objective

To estimate cancer outcome and outcome predictors of women with endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN).

Methods

Outcomes of women with first diagnosis of EIN (“index biopsy”) was determined by follow-up pathology. Patient characteristics were correlated with EIN regression, EIN persistence, and progression to cancer.

Results

Fifteen percent (9.8-20.8%, 26/177) of index EIN biopsies had concurrent cancer. Of the women with cancer-free index EIN biopsies, and follow-up by hysterectomy or more than 18 months surveillance, 25% (18.4-33.3%, 36/142) showed regression, 35% (27.4-43.7%, 50/142) persistence, and 39% (31.3-48.0%, 56/142) progression. Non-white ethnicity and progestin treatment reduced cancer outcomes (OR 0.16 (0.03,0.84) and 0.24 (0.08, 0.70) respectively), while body mass index (BMI) greater than 25 increased malignant outcomes (BMI 25 or higher, OR 3.05 (1.10,8.45)).

Conclusion

EIN confers a high risk of cancer, but individual patient outcomes cannot be predicted. Management should include exclusion of concurrent carcinoma and consideration of hysterectomy.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States with an estimated 40,100 new cases diagnosed annually and 7,470 deaths occurring each year(1). The histopathologic diagnosis of premalignant lesions of endometrioid endometrial cancer has been a source of dispute among pathologists(2). The four-classes of World Health Organization endometrial hyperplasia do not correspond to separate biologic entities, fail to incorporate diagnostic advances achieved in the last 15 years(3), and are poorly reproducible. The alternative EIN schema is a 2-class functionally defined (”benign endometrial hyperplasia”, a hormonal effect; and “EIN” a premalignant lesion) diagnostic system which introduced several newly discovered histologic criteria associated with heightened cancer risk such as minimum lesion size, precise extent of gland crowding, and an internal comparison standard (background vs lesion) for interpretation of significant cytologic change(4). This has proven to be a better predictor of disease progression and equally important, is better able to determine which lesions are likely to remain benign(5). There is no fixed concordance between WHO hyperplasia and EIN schema diagnoses because of differing diagnostic criteria(6).

EIN diagnostic practices have only recently been deployed in routine clinical environments (2001, at our institution) and as a result little has been published regarding care of patients with EIN. The objective of this study was to estimate endometrial cancer outcomes among a series of sequentially diagnosed women with EIN in a tertiary care multi-group practice. In addition, we sought to estimate if there were patient demographic, clinical, or treatment modality characteristics which influenced the outcomes of EIN involution to a benign histology, compared to persistence, or progression to endometrial cancer.

Materials and Methods

This study received approval from the Partners Human Research Committee, the institutional review board for Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). From June 2002 until July 2006, patients receiving a diagnosis of Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia (EIN) upon endometrial sampling at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and its community affiliates were identified through pathology record review. This sample included patients from the gynecology resident continuity practice, faculty clinics, gynecologic oncology clinics, and community health centers and satellite practices. Medical records were obtained from the Partners Health Care electronic medical record system and from paper charts. Demographic data, obstetric history, gynecologic history, medical history, surgical history, operative information, and pathology results were collected from this medical record review.

Inclusion in the study was based on a first pathologic report diagnosis of EIN within an endometrial sample (biopsy or curetting, designated here as an “index biopsy”). Women with previous EIN diagnoses, or endometrial carcinoma, were excluded, as were those in whom the index biopsy histological sections were unavailable for review. The routine pathology interpretations were reported by eleven pathologists at BWH who randomly encountered the specimens as part of rotating service coverage. Diagnosis of EIN required the following: 1) glandular volume exceeding that of stroma; 2) cytological demarcation from surrounding normal glands; 3) lesions with largest diameter greater than 1mm; 4) exclusion of confounding benign processes such as degenerative or hormonal effects; and 5) exclusion of carcinoma(8).

Glass histological sections of the index biopsies were re-reviewed by a single pathologist (GLM), for presence or absence of EIN, and presence or absence of concurrent carcinoma in the same specimen. Since management was based on the pathology report diagnosis, we did not exclude those patients in whom the diagnosis of EIN was not upheld upon re-evaluation of available slides. Follow-up endometrial pathology specimens (obtained after the index EIN biopsy date) varied in number and format (biopsy, curetting, hysterectomy) between patients. Follow-up endometrial specimen pathology reports were reviewed and the outcome censored at first occurrence of carcinoma or last pathology specimen diagnosis. Some women received progestin treatment after initial EIN diagnosis, and these were recorded for analysis.

A retrospective cohort was constructed from those women with cancer-free EIN at initial diagnosis to estimate endometrial cancer outcomes over time. Kaplan-Meier survivor analysis was used to determine the proportion of cancer-free patients during the available follow-up period. Cancer outcomes were then compared for those women who were, or were not, treated after diagnosis with progestins. Outcomes were categorized as cancer if any single follow-up specimen had this diagnosis. For those that did not progress to carcinoma, the outcome was based upon pathology seen in the last available endometrial pathology specimen.

A case-control analysis was then conducted comparing clinical characteristics of women whose EIN regressed (controls) to two separate case groups: women with persistence of EIN on subsequent sampling or hysterectomy and women with a diagnosis of cancer, either in the index biopsy or during follow-up. All controls had either definitive hysterectomy or more than eighteen months of follow-up, to accurately reflect clinical practice outcomes. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square and Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables were compared using t-tests. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate age adjusted odds ratios . Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. SAS statistical analysis software (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to perform all analyses.

Results

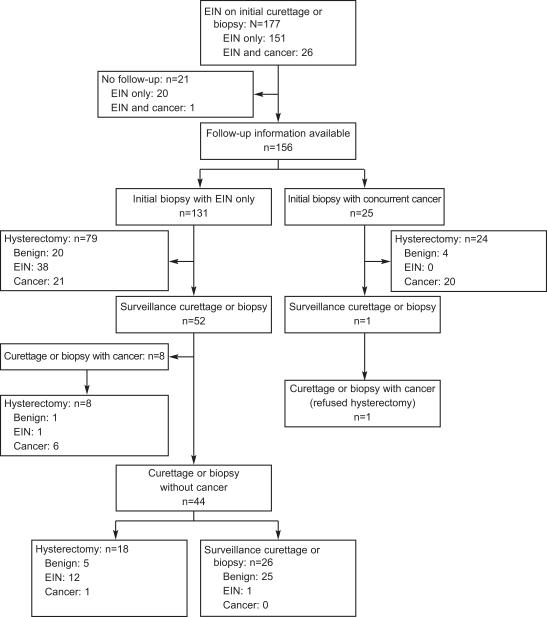

177 new cases of EIN were identified by endometrial sampling from January 2002 through July 2006. All H&E slides were reviewed by a single pathologist, GLM, with a diagnosis of EIN confirmed in 94% of the cases. Patients averaged 53 years of age with a median of 53 and ranged from 26 to 94. Self-reported ethnicity was available for 103 patients. Of these, 81 (78.6% (69.4%-86.1%)) were Caucasian, 8 (7.8% (3.4-14.7%)) were Hispanic, 10 (9.7% (4.7-17.1%)) were African-American, and 4 (3.9% (1.1-9.6%)) were Asian. Figure 1 demonstrates the outcomes of all patients in the study. In 11.9% (7.5-17.6%, 21/177) of cases we had no information regarding follow-up endometrial sampling or hysterectomy, one of which had a concurrent carcinoma in the index biopsy. 82.7% (75.8-88.3%, 129/156) of cases with follow-up eventually had a hysterectomy, of which the majority (70.5% (61.9-78.2%), 91/129) were within 3 months of the index biopsy. 17.3% (11.7-24.2%, 27/156) with available follow-up only had biopsies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants.

Clinical management and clinical outcomes of 177 incident EIN cases. Bracketed numbers show total cases in each node.

Overall cancer incidence was 35.7% (28.2-43.7%, 56/157), diagnosed at various stages of patient management. First diagnosis of carcinoma was most common within the initial EIN-bearing biopsy (26 cases), but others occurred during follow-up biopsy sampling (8 cases), or at definitive hysterectomy (22 cases). Patients with EIN who remained cancer-free during follow-up (102 cases) demonstrated equal frequencies of EIN persistence 50% (40.0-60.1%) (51/102) and “regression” to a benign histology (51/102).

All (56/56) of the endometrial cancers were of the endometrioid (Type I) type. Most (85% (72.9-93.4%), 46/54) were well differentiated, whereas 11% (4.2-22.6%, 6/54) were moderately differentiated, and 4% (0.4-12.7%, 2/54) were poorly differentiated. Grading of two cases was unavailable from the pathology report. 28% (16.4-41.6%, 15/54) of cancers invaded the myometrium, confined to the inner half of the myometrial thickness in 87% (59.5-98.3%) of (13/15) cases. All cases with lymph node sampling (8/8, 63.1%-100%) had cancer free nodes, and only one (1/54, 0.05-9.9%) had myometrial lymphovascular invasion. There were two cases of disease spread beyond the uterine corpus, one metastasis to the ovarian surface and one with local extension to the endocervical stroma.

21% (15.0-28.6%, 32/151) of the women in our study were treated medically with progestins (excluding 26 with unknown treatment status), all were cancer-free in the index biopsy. Cancer outcomes were not significantly different in women treated (22% (9.3-40.0%), 7/32) compared to not treated (39% (30.6-48.9%), 47/119) with progesterone (p=0.095). Women receiving medical therapy by progesterone were significantly younger than those not receiving progesterone (mean age 48.4 versus 54.0 years, P = .012), and were significantly less likely to be parous than women not receiving progesterone therapy (43.3% (25.5-62.6%, 13/30) versus 69.6% (60.3-77.8%, 80/115), P=.01). Amongst women who remained cancer free, the rate of EIN involution as seen by reversion to a benign histology was significantly greater in women treated with progesterone compared to untreated (81% (54.4-96.0%), 13/16 versus 32% (20.6-44.7%), 20/63; p=0.005).

The retrospective cohort analysis was based on 131 patients with a diagnosis of EIN only on initial sampling, and available follow-up. These were variably managed by immediate hysterectomy (60% (51.4-68.7%), 79/131), biopsy surveillance only (20% (13.4-27.7%), 26/131), or biopsy surveillance followed by hysterectomy (20% (13.4-27.7%), 26/131). The pathology outcomes of all 131 patients were 23% (16.0-31.0%, 30/131) endometrial cancer, 39% (30.5-47.8%, 51/131) persistent EIN, and 38% (29.8-47.1%, 50/131) benign pathology.

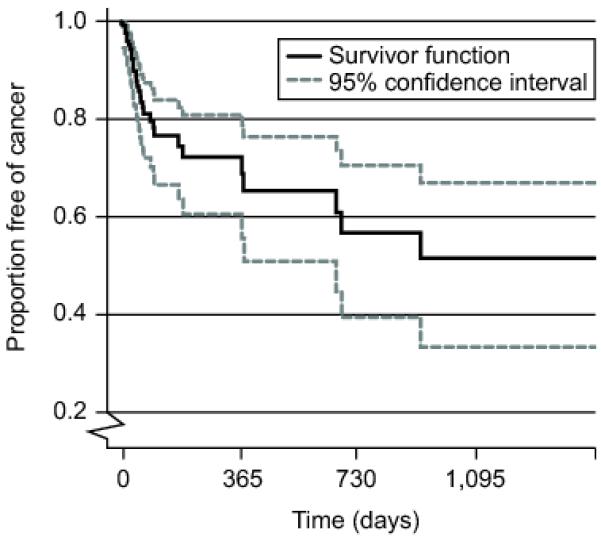

Figure 2 demonstrates the proportion of cancer-free patients during the follow-up period (median 74 days, mean 269 days, and SD 462 days). Interval from index biopsy with EIN to diagnosis of cancer had a median of 56 days (Mean 152 days, and SD 231 days. Of the 30 women who progressed to cancer, 83% (65.3-94.4%, 25/30) were diagnosed within one year and 17% (5.6-34.7%, 5/30) after one year.

Figure 2.

Progression from EIN to Carcinoma.

Kaplan Meyer (“survival”) curve showing proportion (Y axis) of patients with incident EIN remaining cancer free during follow-up (X axis). Gray lines are 95% confidence intervals.

For the case-control analysis, women who did not undergo definitive hysterectomy or who had less than eighteen months of follow-up (n=35) were excluded, leaving a total of 142 cases and controls. Demographic variables including age (p=0.09), ethnicity (p=0.19), marital status (p=0.51), insurance status (p=0.10), and indications for initial endometrial sampling (p=0.15) appeared to be similar (Fishers exact) between those with follow-up and those without (Table 5, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). For those women with adequate followup, demographic, clinical, and reproductive characteristics of women with involuted EIN (controls, n=36, 25% (18.4-33.3%, 36/142) were compared to those women with EIN persistence (cases, n=50, 35% (27.4-43.7%, 50/142) or EIN progression (concurrent or future cancer, cases, n=56, 39% (31.3-48.0%, 56/142).

Table 5.

Patients Included in the Outcome Follow-Up (Greater Than or Equal to 18 Months) Analyses Compared to All Excluded Due to Inadequate (Less Than 18 Months) Follow-Up

| Benigns+EIN+Cancers Included in Analysis (n=142) |

Benigns+EIN Excluded (n=35) |

Fisher’s Exact P-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <49 | 43 (30.3) | 15 (42.9) | 0.09 |

| 49-55 | 51 (35.9) | 6 (17.1) | |

| >55 | 48 (33.8) | 14 (40.0) | |

| Mean (standard error) | 52.8 (9.8) | 53.8 (16.5) | 0.71 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 70 (81.4) | 11 (64.7) | 0.19 |

| Non-white | 16 (18.6) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 46 (33.3) | 11 (40.7) | 0.51 |

| Married | 92 (66.7) | 16 (59.3) | |

| Insurance status | |||

| Free care/Medicaid | 20 (14.5) | 8 (27.6) | 0.10 |

| Private | 118 (85.5) | 21 (72.4) | |

| Indication for initial endometrial sampling |

|||

| Postmenopausal bleeding | 59 (43.1) | 18 (58.1) | 0.15 |

| Heavy bleeding | 29 (21.2) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Irregular bleeding | 27 (19.7) | 2 (6.4) | |

| Other | 22 (16.1) | 7 (22.6) |

EIN, endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia.

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic characteristics of the patients in relation to their outcome diagnosis. Women who had benign pathology did not differ significantly in regards to age, marital status, or insurance status from persistent EIN or cancer cases. Significantly fewer women who had a diagnosis of cancer were of non-white ethnicity (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.03-0.84). “Other” indications for initial biopsy include endometrial cells on pap (8); atypical cells on pap (1); thickened endometrial lining on ultrasound (5); endometrial lesion on imaging (2); evaluation for infertility (2); polyps seen on hysterosalpingogram during evaluation for infertility (1); Lynch syndrome (1); tamoxifen use (1); history of hyperplasia on hormone replacement therapy (1).

Table 1.

Demographic Variables of patients with benign pathology outcomes compared to those with persistent EIN or cancer.

| Variable | Benign N=36 |

Persistent EIN N=50 |

Cancer N=56 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | Age adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

N (%) | Age adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 15 (65.2%) |

31 (83.8%) |

1.00 | 24 (92.3%) |

1.00 |

| Non-white | 8 (34.8%) | 6 (16.2%) | 0.31 (0.09, 1.12) |

2 (7.7%) | 0.16 (0.03, 0.84) |

| Indication for initial endometrial sampling |

|||||

| Postmenopausal bleeding |

13 (39.4%) |

19 (38.8%) |

1.00 | 27 (49.1%) |

1.00 |

| Heavy bleeding | 7 (21.2%) | 16 (32.7%) |

2.00 (0.55, 7.27) |

6 (10.9%) |

0.42 (0.10, 1.87) |

| Irregular bleeding | 8 (24.2%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.99 (0.26, 3.78) |

10 (18.2%) |

0.62 (0.17, 2.30) |

| Other | 5 (15.2%) | 5 (10.2%) | 0.71 (0.17, 3.00) |

12 (21.8%) |

1.17 (0.32, 4.32) |

Clinical variables are shown in Table 2 for each outcome group. Diabetes, hypertension, smoking status, alcohol use, family history of any type of malignancy, and personal history of any prior non-endometrial malignancy did not differ significantly. Body mass index ≥ 25 was significantly associated with increased cancer outcomes (OR 3.05, 95% CI 1.10-8.45).

Table 2.

Body Mass Index of patients with benign pathology outcomes compared to those with persistent EIN or cancer.

| Variable | Benign N=36 |

EIN N=50 |

Cancer N=56 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | Age adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

N (%) | Age adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) |

|||||

| <25 | 12 (38.7%) |

10 (23.8%) |

1.00 | 9 (17.3%) | 1.00 |

| ≥25 | 19 (61.3%) |

32 (76.2%) |

2.02 (0.74, 5.58) | 43 (82.7%) |

3.05 (1.10, 8.45) |

Table 3 compares reproductive history between cases and controls with no significant differences found between the three groups for gravidity, parity, prior tubal ligation, postmenopausal status, postmenopausal bleeding, irregular (premenopausal) menses, polycystic ovarian syndrome diagnosis, ovarian cysts requiring surgery, prior IUD use, and EIN presentation during infertility workup. Amongst four women pursuing infertility treatment at the time of EIN diagnosis, one had EIN involution and three had cancer outcomes (OR 2.81, 95% CI 0.25-31.5).

Table 3.

Reproductive History of patients with benign pathology outcomes compared to those with persistent EIN or cancer.

| Variable | Benign N=36 |

EIN N=50 |

Cancer N=56 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | Age adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

N (%) | Age adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Gravity | |||||

| 0 | 7 (21.2%) |

12 (25.5%) |

1.00 | 11 (21.2%) |

1.00 |

| 1-2 | 18 (54.5%) |

17 (36.2%) |

0.54 (0.17, 1.70) |

16 (30.8%) |

0.57 (0.18, 1.84) |

| >2 | 8 (24.2%) |

18 (38.3%) |

1.39 (0.39, 4.99) |

25 (48.1%) |

2.17 (0.58, 8.05) |

| Mean (std error) | 1.9 (2.0) | 2.2 (2.0) |

1.10 (0.86, 1.41) |

2.6 (2.4) |

1.18 (0.93, 1.50) |

| Parity | |||||

| 0 | 13 (39.4%) |

15 (31.9%) |

1.00 | 17 (32.7%) |

1.00 |

| 1-2 | 13 (39.4%) |

22 (46.8%) |

1.47 (0.53, 4.03) |

21 (40.4%) |

1.22 (0.44, 3.36) |

| >2 | 7 (21.2%) |

10 (21.3%) |

1.23 (0.36, 4.28) |

14 (26.9%) |

1.48 (0.43, 5.09) |

| Mean (std error) | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.6 (1.6) |

1.07 (0.80, 1.43) |

1.7 (1.8) |

1.07 (0.80, 1.43) |

| Status post tubal ligation |

|||||

| No | 26 (89.7%) |

37 (77.1%) |

1.00 | 48 (87.3%) |

1.00 |

| Yes | 3 (10.3%) |

11 (22.9%) |

2.58 (0.65, 10.2) |

7 (12.7%) |

1.30 (0.31, 5.46) |

| Postmenopausal | |||||

| No | 19 (54.3%) |

26 (53.1%) |

1.00 | 26 (47.3%) |

1.00 |

| Yes | 16 (45.7%) |

23 (46.9%) |

0.83 (0.27, 2.60) |

29 (52.7%) |

1.02 (0.32, 3.23) |

| Postmenopausal bleeding |

|||||

| No | 2 (12.5%) |

1 (4.3%) | 1.00 | 1 (3.6%) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 14 (87.5%) |

22 (95.7%) |

3.92 (0.28, 54.9) |

27 (96.4%) |

14.0 (0.54, 364) |

| Irregular periods(premenopausal) |

|||||

| No | 4 (22.2%) |

7 (26.9%) |

1.00 | 9 (34.6%) |

1.00 |

| Yes | 14 (77.8%) |

19 (73.1%) |

0.78 (0.18, 3.31) |

17 (65.4%) |

0.53 (0.13, 2.11) |

| Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome |

|||||

| No | 32 (97.0%) |

45 (91.8%) |

1.00 | 49 (96.1%) |

1.00 |

| Yes | 1 (3.0%) | 4 (8.2%) | 3.75 (0.36, 39.7) |

2 (3.9%) | 1.38 (0.12, 16.4) |

| EIN during infertility treatment |

|||||

| No | 33 (97.1%) |

48 (100%) |

52 (94.5%) |

1.00 | |

| Yes | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (5.5%) | 2.81 (0.25, 31.5) |

|

| Past intrauterine device use |

|||||

| No | 9 (75.0%) |

9 (81.8%) |

1.00 | 22 (95.7%) |

1.00 |

| Yes | 3 (25.0%) |

2 (18.2%) |

0.67 (0.09, 5.07) |

1 (4.3%) | 0.14 (0.01, 1.48) |

Exogenous hormone use is illustrated in Table 4. Use of oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, tamoxifen, and progestin for any indication did not differ significantly between patients with benign outcomes when compared to those with EIN persistence or progression to carcinoma. Progestin use specifically for the treatment of EIN did result in a decreased risk of EIN persistence (OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.03-0.42) and progression (OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.08-0.70).

Table 4.

Hormone Use in patients with benign pathology outcomes compared to those with persistent EIN or cancer.

| Variable | Benign N=36 |

EIN N=50 |

Cancer N=56 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | Age adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

N (%) | Age adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Current oral contraceptive use (premenopausal) |

|||||

| No | 32 (100.0%) |

47 (97.9%) |

53 (100.0%) |

||

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Ever used hormonal replacement therapy (postmenopausal) |

|||||

| No | 8 (53.3%) | 11 (68.8%) |

1.00 | 16 (64.0%) |

1.00 |

| Yes | 7 (46.7%) | 5 (31.3%) | 0.55 (0.12, 2.43) | 9 (36.0%) | 0.65 (0.18, 2.45) |

| Any Tamoxifen use | |||||

| No | 29 (90.6%) |

45 (93.8%) |

1.00 | 54 (98.2%) |

1.00 |

| Yes | 3 (9.4%) | 3 (6.3%) | 0.64 (0.12, 3.38) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.18 (0.02, 1.85) |

| Progestin use | |||||

| Never | 7 (35.0%) | 6 (30.0%) | 1.00 | 16 (48.5%) |

1.00 |

| Former | 6 (30.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 1.47 (0.31, 6.93) | 11 (33.3%) |

0.84 (0.22, 3.25) |

| Current | 7 (35.0%) | 6 (30.0%) | 0.98 (0.21, 4.62) | 6 (18.2%) | 0.37 (0.09, 1.52) |

| Progestin used for EIN |

|||||

| No | 20 (60.6%) |

43 (93.5%) |

1.00 | 47 (87.0%) |

1.00 |

| Yes | 13 (39.4%) |

3 (6.5%) | 0.11 (0.03, 0.42) | 7 (13.0%) | 0.24 (0.08, 0.70) |

Discussion

Diagnostic classification of premalignant endometrial lesions is now in a state of transition from the legacy 4-class WHO 1994 hyperplasia schema (hyperplasia with or without atypia, complex or simple architecture) to a 2-class EIN schema (benign endometrial hyperplasia/EIN)(8). Advantages of the EIN system are better defined histopathologic diagnostic criteria, superior clinical outcome prediction, and lucid communication for each diagnosis of the disease process (hormonal/premalignant)(4;7). By entering all sequential patients with a first diagnosis of EIN within a defined practice environment, we have minimized case selection bias and are able to generate a practitioner’s view of current management practices, clinical outcomes, and demographics of affected patients using the EIN diagnostic approach. Pathologic diagnosis of EIN was highly consistent amongst pathologists, with the initial diagnoses (made by a pool of 11 surgical pathologists) confirmed upon central review in 94% of cases.

EIN is a high risk factor for malignancy, with 35.7% (28.2-43.7%, 56/157) overall having or developing carcinoma. Among women diagnosed with EIN, 15% (9.8-20.8%, 26/177) had concurrent cancer in the presenting biopsy, 19% (12.7-26.9%, 25/131) developed cancer within one year, and an additional 4% (1.2-8.7%, 5/131) after one year. This compares to a 37.8% (56/148) synchronous cancer rate in women with EIN undergoing immediate hysterectomy (9), and a 41% cancer rate during one year of clinical follow-up (7). Prior estimates of concurrent endometrial cancer at the time of diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia are similar, at 43% for immediate hysterectomy(10). Short follow-up interval in our series precluded estimates of additional longer term progression events to carcinoma, but other studies have shown that cancer occurrences beyond 1 year of EIN diagnosis are 45 times more likely than EIN free women, occurring in 18% of patients at a median interval of 4 years (average 4.1 years)(7). Although we have used the term cancer “progression” throughout for cancers diagnosed after the initial EIN bearing biopsy, some unknown proportion of these represent occult carcinomas present in the patient, but missed by biopsy, at the time of initial EIN diagnosis.

Our case control analysis showed that overweight and obese women with EIN (body mass index ≥25) were at 3.05 fold increased risk for development of endometrial cancer compared to non-obese patients with EIN. This is consistent with prior epidemiologic data in which obesity is a risk factor for endometrial carcinoma, perhaps mediated by changes in endogenous steroid hormone metabolism (11;12). We did not have sufficient numbers of morbidly obese (BMI>38) patients to determine whether the risk effect is proportionately scaled across the full range of body weights, or is a discrete threshold effect.

Progestin treatment of EIN, most common in younger nulliparous patients desiring to maintain fertility, was utilized in 21% (15.0-28.6%, 32/151) of our study population and associated with decreased risk for EIN persistence (OR 0.11), or progression to carcinoma (OR 0.24). This coincides with a developing experience showing that progestin therapy may in some cases be effective in nonsurgical treatment of endometrial precancers(13;14) or even carcinoma(15). In general, however, accurate estimates of efficacy are severely limited by lack of standardization of therapeutic regimen (agent, dosage, and administration schedule) in addition to uncertainty of the best outcome measures (number of biopsies, surveillance duration, and validity of on-agent samples). Long term failures require more protracted clinical follow-up than generally available, and there are limitations to pathologic interpretation of residual disease in an endometrial sample obtained under the influence of active progestational therapy which dramatically alters lesion cytology and architecture(15;16). Thus, some of the “benign” outcomes may be occult EIN persistence missed by the pathologist, and others a transient shrinkage of EIN lesions, rather than long term cure. Our own study is constrained by thesefactors, and best interpreted as evidence of a short term therapeutic response rather than permanent “cure”. More studies, preferably with multiple surveillance biopsies following completion of progestin therapy, need to be done to determine the long term natural history of these patients.

Endometrioid carcinoma and EIN have a common pathogenesis, and thus share many overlapping risk factors that require large numbers of patients to resolve separately. Our study sample size may have limited our power to detect risk factors specific to the EIN patient which predict cancer outcomes. Furthermore, human studies constraints in this retrospective context prohibited contacting patients and thus we were unable to utilize standardized exposure questionnaires.

All cancer outcomes seen in our study were of an endometrioid histologic type, usually well differentiated, with superficial or no myometrial invasion. However, there were two patients with greater than 50% myometrial invasion, and another two patients with evidence of disease beyond the uterine corpus. Careful clinical evaluation of the possibility of concurrent carcinoma is advised in all new diagnoses of EIN. In those cases where surgical management is the treatment chosen, examination of the hysterectomy specimen will perform this function.

Our experience with EIN is that it is a reproducible and specific diagnosis that allows us to identify those premalignant endometrial lesions that place a patient at risk for carcinoma. Management of EIN lesions should consider the heightened cancer risk that diagnosis confers, and generally follow those guidelines previously established for atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Given the high likelihood of concurrent malignancy, women identified as having EIN lesions warrant close follow-up and consideration of treatment with hysterectomy. Younger women wishing to retain fertility are in some cases being managed with progestin therapy and we did find this may promote involution of EIN to a benign histology and reduce the progression likelihood to carcinoma. Despite these promising data, lack of therapeutic standardization, defined endpoints, and prospective blinded measures of treatment efficacy are limitations to assessment of the risks and benefits of this approach.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant RO1-CA100833 (G. Mutter).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists in Waltham, MA (Semere, July 14, 2010) and the Japanese Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology 61st annual meeting in Kyoto, Japan (Ko, April 3-5, 2009).

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2008. Available: http://seer cancer gov/csr/1975_2005/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mutter GL, Matias-Guiu X, Lax SF. Endometrial Adenocarcinoma. In: Robbboy SJ, Mutter GL, Prat J, Bentley RC, Russell P, Anderson MC, editors. Robboy’s Pathology of the Female Reproductive Tract. 2 ed. Elsevier; New York: 2009. pp. 393–426. New York. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokhman J. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983;15:10–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(83)90111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecht JL, Ince TA, Baak JP, Baker HE, Ogden MW, Mutter GL. Prediction of endometrial carcinoma by subjective endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 2005 Mar 1;18:324–30. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mutter GL. Histopathology of genetically defined endometrial precancers. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19:301–9. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mutter GL, The Endometrial Collaborative Group Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN): Will it bring order to chaos? Gynecol Oncol. 2000;76:287–90. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baak JP, Mutter GL, Robboy S, van Diest PJ, Uyterlinde AM, Orbo A, et al. The molecular genetics and morphometry-based endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia classification system predicts disease progression in endometrial hyperplasia more accurately than the 1994 World Health Organization classification system. Cancer. 2005 Jun 1;103(11):2304–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mutter GL, Zaino RJ, Baak JPA, Bentley RC, Robboy SJ. The Benign Endometrial Hyperplasia Sequence and Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2007;26:103–14. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31802e4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutter GL, Kauderer J, Baak JPA, Alberts DA. Biopsy histomorphometry predicts uterine myoinvasion by endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:866–74. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ, et al. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006 Feb 15;106(4):812–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiderpass E, Adami HO, Baron JA, Magnusson C, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, et al. Risk of endometrial cancer following estrogen replacement with and without progestins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Jul 7;91(13):1131–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parazzini F, Vecchia C La, Bocciolone L, Franceschi S. The epidemiology of endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;41:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Signorelli M, Caspani G, Bonazzi C, Chiappa V, Perego P, Mangioni C. Fertility-sparing treatment in young women with endometrial cancer or atypical complex hyperplasia: a prospective single-institution experience of 21 cases. BJOG. 2009 Jan;116(1):114–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varma R, Soneja H, Bhatia K, Ganesan R, Rollason T, Clark TJ, et al. The effectiveness of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) in the treatment of endometrial hyperplasia--a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008 Aug;139(2):169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheeler DT, Bristow RE, Kurman RJ. Histologic alterations in endometrial hyperplasia and well-differentiated carcinoma treated with progestins. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007 Jul;31:988–98. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31802d68ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin MC, Lomo L, Baak JPA, Eng C, Ince TA, Crum CP, et al. Squamous Morules Are Functionally Inert Elements of Premalignant Endometrial Neoplasia. Mod Path. 2009;22:167–74. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]