Abstract

Controlled biodegradation specific to matrix metalloproteinase-13 was incorporated into the design of self-assembling β-hairpin peptide hydrogels. Degrading Peptides (DP peptides) are a series of five peptides that have varying proteolytic susceptibilities towards MMP-13. These peptides undergo environmentally triggered folding and self-assembly under physiologically relevant conditions (150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) to form self supporting hydrogels. In the presence of enzyme, gels prepared from distinct peptides are degraded at rates that differ according to the primary sequence of the single peptide comprising the gel. Material degradation was monitored by oscillatory shear rheology over the course of 14 days, where overall degradation of the gels vary from 5% to 70%. Degradation products were analyzed by HPLC and identified by electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry. This data shows that proteolysis of the parent peptides constituting each gel occurs at the intended sequence location. DP hydrogels show specificity to MMP-13 and are only minimally cleaved by matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3), another common enzyme present during tissue injury. In vitro migration assays performed with SW1353 cells show that migration rates through each gel differs according to peptide sequence, which is consistent with the proteolysis studies using exogenous MMP-13.

Introduction

Hydrogels are a class of biomaterials that are finding use as scaffolds in soft tissue engineering and wound healing [1–15]. Attractive properties of hydrogels for wound healing applications include high water content, mechanical rigidity and porosity. Primarily, a hydrogel is intended to act as a provisional matrix at a site of tissue injury. Ideally it should have a degradation rate that approximates the rate of formation of new cell-secreted extracellular matrix. This results in optimal tissue integration and mechanically stability comparable to uninjured native tissue [6, 8]. Thus, optimal tissue regeneration should occur when the temporary hydrogel support is degraded within an appropriate time scale.

Synthetic polymer hydrogels have been previously utilized as degradable scaffolds for tissue reconstruction therapies [16]. Common degradable functional groups incorporated into polymeric biomaterials include poly(esters), poly(anhydrides) and poly(ortho-esters) [17]. The rate of degradation of these polymeric materials depends on the rate of hydrolysis of their respective functional groups, which is governed by solution pH, water uptake into the hydrogel and exact composition of the network [17]. Thus, control over the degradation rate is largely limited to the action of bulk water.

Upon tissue injury, enzymes are utilized to breakdown damaged extracellular matrix components [18, 19]. Typically, enzymes catalyze amide bond hydrolysis of extracellular matrix protein macromolecules, such as collagen. Degradable hydrogel networks have been designed to exploit these secreted proteases to further control degradation rates. In particular, peptide sequences corresponding to the cleavage site of trypsin [20], neutrophil elastase [21], subtilisin [22], pepsin [23], papain [24] and more broadly applicable, matrix metalloproteinases [20, 25–36], have been incorporated into hydrogel networks to control material resorption.

A tissue of particular interest for regeneration purposes is cartilage, as it is avascular and thus has a poor capacity to repair itself [8, 37, 38]. During cartilage injury, a host of matrix degrading enzymes are expressed to breakdown the damaged ECM. In particular, matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) expression is upregulated ~2-fold [39]. MMP-13 plays an integral role in degrading damaged extracellular matrix components, such as collagen, gelatin and fibronectin, to name a few, to make space for new extracellular matrix deposition [40]. For this reason, MMP-13 has been targeted in biomaterial designs to enzymatically degrade peptide-polymer based hydrogels [27, 30–32]. In this manuscript, we described a class of hydrogels formed from self-assembling peptides that takes advantage of the activity of MMP-13 to control degradation.

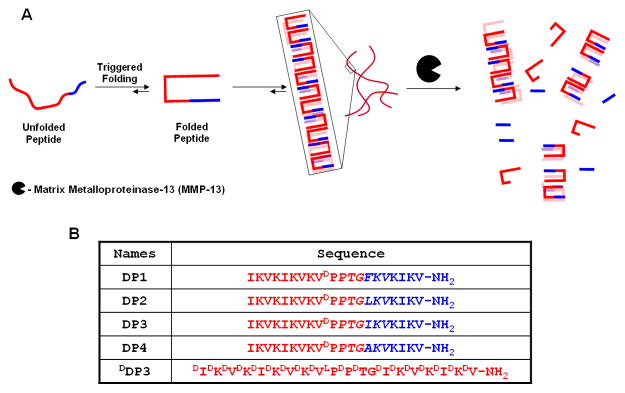

Degrading Peptides (DP) are a new series of de novo designed, 20-amino acid containing sequences that incorporate MMP-13 specific cleavage sites that vary in their respective MMP-13 susceptibilities. These peptides are designed to undergo triggered intramolecular folding into a conformation capable of rapid self-assembly affording fibril networks with a spectrum of degradation profiles, Figure 1A. Individual DP peptides are composed of N- and C-terminal stand regions that have alternating hydrophobic (isoleucine or valine) and hydrophilic lysine residues. A central four residue sequence (-VDPPT-) connects the two stand regions and is designed to adopt a type II′ β-turn when folding is triggered, Figure 1B. Hydrogel formation is initiated with temporal resolution by controlling the folded state of the peptide. At neutral pH and low ionic strength, electrostatic repulsion between protonated lysine side chains keeps the peptide unfolded, disfavoring self-assembly, Figure 1A. Increasing the ionic strength with NaCl to 150 mM screens the positive charge, allowing the peptide to fold into a facially amphiphilic β-hairpin. Once folded, these peptides are designed to self assemble into a β-sheet rich network of fibrils where each fibril is composed of a bilayer of folded hairpins that have hydrogen-bonded along the fibril long axis, Figure 1A. The resulting network of fibrils constitutes a self-supporting hydrogel. Detailed investigations on other self-assembling β-hairpin peptides support this mechanism [41–43].

Figure 1.

(A) Environmentally triggered folding and self-assembly leading to hydrogelation. Subsequent biodegradation of β-hairpin hydrogels. (B) Sequences of MMP-13 susceptible β-hairpin peptides.

To impart susceptibility to MMP-13, DP peptides were designed with an MMP-13 cleavable, six residue sequence, PTG-XKV, at the C-terminus of the peptide, Figure 1B. The sequence includes a proline at the P3 position, a small amino acid at the P1 (glycine) position, a basic amino acid at the P2′ (lysine) position and a hydrophobic residue at the P3′ (valine) position of the substrate [44, 45]. To vary the biodegradation rates, the amino acid at the P1′ position was varied to include isoleucine (Ile), leucine (Leu), phenylalanine (Phe) or alanine (Ala). MMP-13 has a large hydrophobic binding pocket in the S1′ subsite, that can accommodate large hydrophobic amino acids at the P1′ position [46]. As the hydrophobicity of the residue occupying the P1′ position decreases, the relative rates of biodegradation should also decrease [47]. Therefore, the ease by which MMP-13 should degrade a given hydrogel network should follow DP2 (X = Leu) > DP3 (X = Ile) ~ DP1 (X = Phe) > DP4 (X = Ala). In addition to these gels, a control gel, DDP3, was prepared from the enantiomer of DP3, which primarily consists of residues of D-chirality. Gels prepared from the DDP3 peptide should not be degraded. The degradation of the DP peptide family was assessed over a 14 day time period by monitoring the mechanical properties of the hydrogels exposed to MMP-13 by oscillatory rheology. Gel degradation products were characterized by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry. Lastly, in vitro migration assays were performed for selected gels employing SW1353 cells induced to secrete MMP-13; these migration studies investigate the possibility of controlling migration rates by manipulating the networks’ susceptibility to MMP-13 degradation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

PL-Rink Amide resin was purchased from Polymer Laboratories. 2-(6-chloro-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate (HCTU) was purchased from Peptides International. Piperidine and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All Fmoc-protected amino acids were purchased from NovaBiochem. Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), trifluoroacetic acid, ethanedithiol, anisole and thioanisole were purchased from Acros. Diethyl ether, acetonitrile (MeCN), methanol, Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane), sodium chloride, calcium chloride, zinc sulfate and hydrochloric acid were purchased through Fisher. Proteolytic enzymes, matrix metalloproteinase-13 (Leinco Technologies, M1242) and matrix metalloproteinase-3 (Enzo Life Sciences, ALX-201-042-C005), were utilized in the rheological proteolysis experiments. SW1353 cells (primary grade II chondrosarcoma cells) were purchased from ATCC® (Cat. HTB-94). Cells were grown in DMEM (Sigma D6546) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS (Hyclone SH30088.03), L-Gln (Sigma G7513) and Gentamicin (Sigma G1397) in a T75 flask (Corning 430641). The cells were passaged every 2 to 3 days, until needed, by rinsing with PBS (Sigma D8537) and detached by the addition of 0.25 w/v% trypsin (Hyclone SV30031.01) for 3 to 5 minutes. When cells were harvested for experiments, they were detached and counted via hemocytometry, and used immediately.

Peptide Synthesis

DP1, DP2, DP3, DP4 and DDP3 were synthesized by automated solid phase peptide synthesis on PL-rink amide resin utilizing Fmoc-based peptide chemistry on an ABI 433A peptide synthesizer with HCTU activation [60]. The resin-bound peptides were cleaved and their respective side chains deprotected using a cleavage cocktail of TFA:thioanisole:ethanedithiol:anisole (90:5:3:2) for 2 hrs under Ar(g) atmosphere. The resin was then removed by filtration, the TFA was evaporated with a slow stream of Ar(g) and the peptides were precipitated from the filtrate with cold diethyl ether. The resulting crude peptides were purified by RP-HPLC (Vydac C18 peptide/protein column) at a flow rate of 8 mL/min and at a temperature of 40°C. DP1 was purified utilizing an isocratic gradient of 0% Std. B over 2 minutes, followed by a linear gradient of 0% to 21% Std. B over 8 minutes and then 21% to 100% Std. B over 166 minutes. DP2, DP3 and DDP3 were purified utilizing an isocratic gradient of 0% Std. B for 2 minutes, followed by employing a linear gradient of 0% to 22% Std. B over 8 minutes and then 22% to 100% Std. B over 164 minutes. DP4 was purified utilizing an isocratic gradient of 0% Std. B over 2 minutes, followed by employing a linear gradient of 0% to 17% Std. B over 8 minutes, and then 17% to 100% over 174 minutes. HPLC solvents consisted of Standard A (0.1% TFA in H2O) and Standard B (90% MeCN, 9.9% H2O and 0.1% TFA). Purified peptide solutions were frozen with N2(l) and lyophilized, resulting in a pure peptide powder that was utilized for all respective experiments. The purity of each peptide was assessed by analytical HPLC and ESI-MS. (See Supporting Information)

Oscillatory Shear Rheology of Non-proteolyzed Hydrogels

Oscillatory shear rheology experiments were conducted on a TA Instruments AR-G2 rheometer with a 25 mm stainless steel parallel geometry at a gap height of 0.5 mm. One weight percent (1 wt%) gels were prepared directly on the rheometer as follows. First, 200 μL of a 2 wt% peptide solution was prepared by dissolving 4 mg of peptide in 200 μL of H2O. Then 200 μL of buffer (100 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM CaCl2, 80 μM ZnSO4, pH 7.6) was added to the peptide solution. A volume of 320 μL of the resulting peptide solution (1 wt% peptide, 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM CaCl2, 40 μM ZnSO4, pH 7.6) was then immediately transferred to a 5°C pre-equilibrate rheometer. Time-sweep experiments were performed by lowering the upper geometry to a 0.5 mm gap height. A thin layer of S6 oil was added to the edge of the plate to prevent evaporation. The temperature was then increased linearly from 5°C to 37°C for DP2, DP3 and DDP3, and 5°C to 60°C for DP1 and DP4 over 110 seconds at a frequency of 6 rad/s and 0.2% strain. After which, the temperature was held constant at 37°C for DP2, DP3 and DDP3 (or 60°C for DP1 and DP4). Here, increasing the ionic strength as well as the temperature triggers hydrogelation. The storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli were monitored as a function of time (2 hours). On completion of the dynamic time sweep, the 1 wt% peptide hydrogel was subjected to a dynamic frequency sweep, where 40 data points were collected between 0.1 and 100 rad/s keeping strain (0.2%) and temperature constant at 37°C (or 60°C for DP1 and DP4). Subsequently the peptide hydrogel was exposed to a dynamic strain sweep where 40 data points were collected between a range of 0.01% and 1000% strain keeping temperature and frequency constant at 37°C (or 60°C for DP1 and DP4) and 6 rad/s respectively. Full rheological characterization of all DP peptides is located in the Supporting Information.

Rheological Assessment of Proteolysis

Proteolysis experiments were conducted with 80 μL of 1 wt% DP hydrogels in a flexiPERM ® (Greiner) reusable chamber equipped with ethylene vinyl acetate plugs. Gels were prepared by first preparing 40 μL of a 2 wt% peptide solution in H2O and subsequently adding 40 μL of buffer (100 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM CaCl2, 80 μM ZnSO4, pH 7.6). The resulting solutions were incubated at 37°C (or 60°C for DP1 and DP4) for 2 hours to allow the gels to set, after which 80 μL of buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM CaCl2, 40 μM ZnSO4, pH 7.6) was introduced on top of the hydrogels. The gels were then allowed to equilibrate overnight at 37°C (or 60°C for DP1 and DP4). After the overnight equilibration, the supernatant was removed and 80 μL of 80 nM MMP (MMP-13 or MMP-3) was introduced to the top of the peptide hydrogel. For the control gel, 80 μL of buffer without enzyme (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM CaCl2, 40 μM ZnSO4, pH 7.6) was added. All gels were placed in an incubator at 37°C. The gels were incubated for either 1 day, 7 days or 14 days. At each time point, the supernatant was removed from the top of the hydrogel and the hydrogel was gently removed from the ethylene vinyl acetate plug and transferred to the rheometer, pre-equilibrated at 37°C. The 8 mm parallel plate was then lowered to its measuring position (0.5 mm) and a thin layer of S6 oil was added to the outside of the tool to prevent evaporation. A dynamic time sweep (6 rad/s, 0.2% strain) was preformed for 10 minutes to allow the gel to equilibrate. After which, a dynamic frequency sweep was performed from 0.1 to 100 rad/s at 0.2% strain to measure G′ and G″ in the linear regime. The normalized G′ data was calculated at a frequency of 6.31 rad/s. Time, frequency and strain sweeps of all the gels in the absence of enzyme are reported in the Supporting Information. In these experiments, gels were prepared directly on the rheometer and a 25 mm tool was employed, as opposed to being transferred to the rheometer and using a 8 mm tool, as was the case for the proteolytic experiments. Hydrogels prepared directly on the rheometer and the use of a smaller tool show a diminished frequency dependency on their respective G′ as compared to gels transferred to the rheometer. For the experiments at high concentration of MMPs, the aforementioned procedure was utilized with the exception that 800 nM MMP (either MMP-13 or MMP-3) was added on top of the 1 wt% peptide hydrogels. Rheological measurements were taken at 1, 3 and 7 days. For all experiments, the enzyme was replenished every 3 days.

Sequence Determination of Proteolytic Fragments

Following the completion of the rheological assessment of the proteolyzed hydrogels, the oil was removed from around the gels and the upper geometry of the rheometer was raised. The remaining gel was removed with a microspatula and placed in a 1.5 mL eppendorf tube. The gel was dissolved in 200 μL of Std. A, followed by the addition of 200 μL of hexanes to extract any residual oil. The hexanes and Std. A layers were mixed vigorously and then allowed to separate into two distinct layers. A volume of 150 μL of the aqueous layer, where the peptide resides, was removed and injected on an Agilent 1200 series analytical HPLC. A linear gradient of 0% to 100% Std. B over 100 minutes was employed at a temperature of 40°C. The separated fragments were collected, frozen with N2(l) and then subsequently lyophilized. The lyophilized peptide fragments were then dissolved in 50 μL of 1:1 MeOH:H2O and subjected to ESI-MS. The observed m/z peaks were used to determine the identity of peptide fragments.

Live/Dead Cell Viability Assay

A 1 wt% stock DP peptide solution was first prepared in 0.2 μm filtered milli-Q water. A volume of 75 μL of peptide solution was added to a well of a chambered coverglass system (Lab-Tek II). An equal volume of FBS-free DMEM was added to the well containing the peptide solution, to initiate gelation. The gels were placed in an incubator, set at 37°C, for 2 hours. After which, an extra 150 μL of FBS-free DMEM was added on top. The next day 20,000 SW1353 cells in DMEM containing 10% FBS, were introduced to the top of the DP hydrogels. After incubating at 37°C for 24 hours, the DP hydrogels with the cells were rinsed two times with FBS-free DMEM and stained with DMEM containing 2 μM calein AM (Invitrogen) and 4 μM ethidium homodimer (invitrogen). Images were taken on a laser scanning confocal microscope, where live cells fluoresce green (calcein AM) and dead cells fluoresce red (ethidium homodimer).

Cellular Invasion Assay

Gels (0.5 wt%) were prepared in trans-well inserts ~12–16 hours prior to the assay. Briefly, a 1 wt% DP aqueous peptide solution was first prepared by dissolving peptide into milli-Q water. A volume of 7.5 μL of the 1 wt% aqueous solution was added to the cell culture insert (BD 353097). An equal volume of FBS-free DMEM was added to the peptide solution to induce gelation. The gels were placed in an incubator at 37°C and were allowed to cure for 2 hours. After which, 45 μL of FBS-free DMEM was added to the top of gels, and the inserts were promptly placed back in the incubator. The following day 30,000 cells were introduced to the top of the gels and DMEM containing 0.1% FBS was added to each insert to a final volume of 200 μL. The control experiment consisted of cells introduced to the top of the inserts alone without gel. Additionally, 2 μL of 10 ng/mL of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) or milli-Q water was added to the top of the gel or control surface, respectively. The inserts were then immediately placed in 1 mL of 10% FBS DMEM (supplemented with 2 mM L-Gln and gentamycin) in a 24 well plate. After a specified period of time (24, 48 or 72 hours), the cells that migrated through the 0.5 wt% peptide hydrogel were stained with a Diff-Quick staining kit according to manufacturer’s protocol. Images were taken on a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL inverted microscope with an Axio Cam ICc3 camera. Quantitative analysis was preformed by utilizing ImageJ imaging software.

Results and Discussion

Folding, self-assembly and ultimate gelation of a given DP peptide can be triggered by the addition of saline buffer (100 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM CaCl2, 80 μM ZnSO4, pH 7.6) to an aqueous solution of unfolded peptide. This mechanism of triggered intramolecular folding followed by self-assembly into fibrils is supported by spectroscopic, microscopy and scattering studies of β-hairpin peptides previously reported by our group [48–53]. For the DP peptides, gelation was monitored rheologically. Within minutes of triggering peptide folding and assembly, DP1, DP2, DP3, DP4 and DDP3 formed moderately rigid gels having storage moduli (G′) of 820 Pa, 1900 Pa, 2800 Pa, 350 Pa and 2600 Pa, respectively (see Supporting Information).

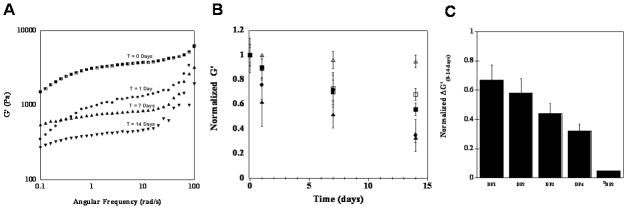

After the gels were formed, network degradation by MMP-13 was assessed for a 14 day time period by dynamic oscillatory shear rheology. Here, the mechanical rigidity, or storage modulus (G′), was measured at 0, 1, 7, and 14 day intervals for 1wt% hydrogels of DP1, DP2, DP3, DP4, DP5, and DDP3. For example, Figure 2A shows representative frequency sweep data for the DP1 gel in the presence of MMP-13 as a function of time. The storage modulus decreases as expected with the gel losing 67% of its original value after 14 days. In addition, after 14 days, the G′ of the gel shows a greater dependency on the angular frequency at the higher frequencies examined. This is consistent with the evolution of a less rigid gel as a result of enzymatic cleavage of the network. Figure 2B shows the average G′ values, at a frequency of 6 rad/sec for all gels in the presence of MMP-13 as a function of time. Here, the data is normalized to aid the comparison between gels. A time dependent decrease in the mechanical rigidity was observed for the cleavable gels suggesting that the individual DP peptide molecules that comprise the network are being proteolyzed over time. Figure 2C shows the relative change in the storage moduli of the proteolyzed gels after 14 days compared to the normalized G′ at the start of the experiment. The greatest fraction loss of mechanical rigidity, 0.65, was observed for the DP1 gel. About 0.58 and 0.44 was observed for the DP2 and DP3 hydrogels, respectively. The DP4 hydrogel has a modulus that is 0.32 of its original modulus indicating that this network is most resistant to degradation. The control DDP3 hydrogel showed little to no degradation with a 0.05 fraction loss. This indicates that MMP-13 is unable to act on this peptide network and strongly suggests that the decrease in mechanical integrity observed for the other peptide gels is due to the action of MMP-13.

Figure 2.

(A) Angular frequency sweep of 1.0 wt%DP1 hydrogels exposed to MMP-13 as a function of time. (B) Relative rheological assessment of DP hydrogels exposed to MMP-13 over a 14 day time period. DP1 (▲), DP2 (●), DP3(■), DP4 (□) and DDP3 (△); Normalized G′ = G′ MMP/G′ Control. (C) Relative change in the normalized G′ from day 0 to day 14.

With respective to sequence specificity, the expected order in which gels are most quickly degraded should follow DP2 (X = Leu) > DP3 (X = Ile) ~ DP1 (X = Phe) > DP4 (X = Ala). This is because residues with greater hydrophobicity should bind the S1′ pocket more favorably. However, the trend observed for the DP hydrogels is slightly different with the DP1 gel being degraded most easily. This may be due to the fact that the DP1 gel is the least rigid network in the series (G′ = 820 Pa) and accordingly its network should have fewer crosslinks and larger pores compared to the other peptide networks [54, 55]. Thus, MMP-13 can penetrate and degrade the network more readily, as compared to other DP hydrogels. The rheological data taken together, suggests that both peptide sequence specificity and network morphology dictate the rate of degradation.

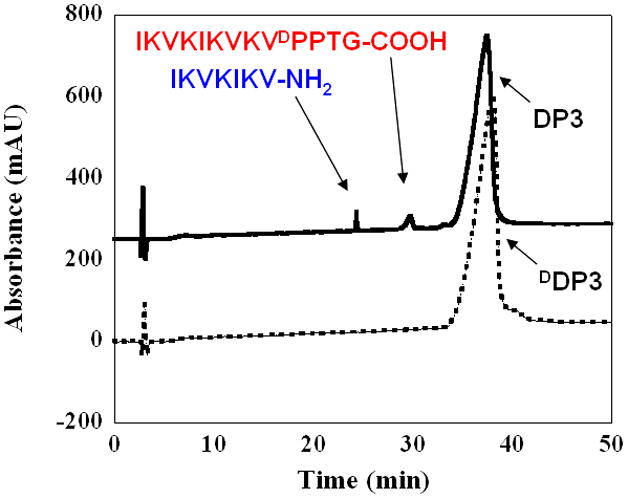

The MMP-13 proteolyzed gels at day 14 were resolubilized and peptide fragments resulting from enzymatic cleavage were characterized by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). HPLC allowed for chromatographic separation of the cleaved peptide fragments from the network, where as ESI-MS was utilized to chemically identify the mass of these fragments. Figure 3 depicts a representative chromatograph showing peptide fragments formed from the DP3 hydrogel after exposure to MMP-13 for 14 days. Three peaks eluting at 24, 29 and 35 minutes, are observed and correspond to IKVKIKV-NH2, IKVKIKVKVDPPTG-COOH and the full length DP3 peptide sequence, respectively. The proteolysis fragments observed are consistent with cleavage occurring at the intended position between the amino acids glycine and isoleucine, -PTG-IKV-. DP1 and DP2 showed similar HPLC chromatograms and mass spectroscopy indicates that cleavage had occurred at the intended site, see Supporting Information. Peptide fragments from the DP4 hydrogel, which showed the least diminution of mechanical rigidity, could not be detected. This is most likely due to their low concentration in the network. DDP3 exposed to MMP-13 for the same duration yielded a chromatogram having one peak that corresponds to the full length DDP3 peptide, Figure 3. In sum, the LC-MS data shows that the enzyme is acting on the intended amide bond and is responsible for the mechanical degradation of the network.

Figure 3.

Chromatograms of DP3 (—) and DDP3 (

) hydrogels after being exposed to MMP-13 for 14 days showing full length peptides and corresponding proteolyzed fragments.

) hydrogels after being exposed to MMP-13 for 14 days showing full length peptides and corresponding proteolyzed fragments.

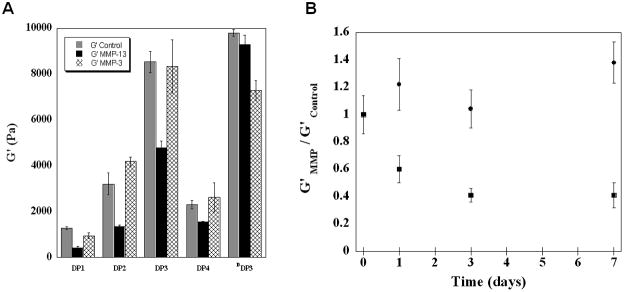

During cartilage injury, other MMPs in addition to MMP-13 are expressed to degrade the damaged tissue. In particular, MMP-3 has been shown to be upregulated in damaged cartilage explants after mechanical injury [39]. Although MMP-3 should cleave the same amide bond within a given DP peptide as MMP-13, it has a slightly different sequence preference [56, 57]. To investigate the selectivity of the design and relative susceptibilities of the DP hydrogels to proteolysis by MMP-3, a 14 day rheological study was also performed in the presence of this enzyme. Here, DP hydrogels were exposed to 40 nM of MMP-3 for 14 days, after which the mechanical properties were assessed by oscillatory shear rheology and compared to the properties of the same gels that have been exposed to MMP-13 and to control gels that had never been exposed to enzyme, Figure 4A. First, hydrogels that had been exposed to MMP-3 exhibit a G′ that is comparable to the buffer control (compare grey and hatched bars). This data suggests that MMP-3 has little or no effect on the mechanical properties of any of the DP hydrogels. In contrast, hydrogels exposed to MMP-13 show a sequence dependent decrease in their respective G′ (compare grey and black bars). The selectivity of enzymatic action was further studied by exposing the DP3 hydrogel to an excessively large concentration of either MMP-3 or MMP-13. Figure 4B shows that even when exposed to 400 nM of MMP-3, there is little change in the gels rheological behavior. In contrast, the gel is clearly susceptible to MMP-13 degradation. Subsequent HPLC analysis was also performed on the DP3 hydrogels exposed to MMP-13, MMP-3 or buffer control, see Supporting Information. Consistent with the rheological results, the DP3 chromatograms illustrate significant amount of proteolysis when exposed to MMP-13. In the presence of MMP-3, very minute proteolysis peaks are observed, that correspond to IKVKIKV-NH2, IKVKIKVKVDPPTG-COOH and full length DP3 peptide. Therefore, when there is a gross amount of enzyme present, a small amount of MMP-3 based cleavage is occurring which is not significant enough to influence the storage modulus of the gel.

Figure 4.

(A) Rheological assessment of DP hydrogels exposed to buffer (

) as the control, 40 nM MMP-13 (■) or 40 nM MMP-3 (⊠) after 14 days. (B) Relative rheological assessment of proteolysis of DP3 exposed to high concentration (400 nM) of MMP-13 (■) or to 400 nM MMP-3 (●).

) as the control, 40 nM MMP-13 (■) or 40 nM MMP-3 (⊠) after 14 days. (B) Relative rheological assessment of proteolysis of DP3 exposed to high concentration (400 nM) of MMP-13 (■) or to 400 nM MMP-3 (●).

The inability of MMP-3 to degrade the DP gel networks may be due to its slight difference in sequence preference as compared to MMP-13. In addition, the network morphology may also be playing a role. MMP-3 may be unable to access the peptide in its self-assembled state, while MMP-13 can. In fact, literature reports indicate that MMP-3, although capable of degrading denatured collagen, has limited ability to act on native collagen [40]. This suggests that the active site of MMP-3 has limited capacity to accommodate its substrate if it is self-assembled. In contrast, its been shown that MMP-13 can readily degrade native collagen. Thus, the reported enzymatic behaviors of MMP-3 and MMP-13 are consistent with their observed activity towards the DP gels, Figure 4.

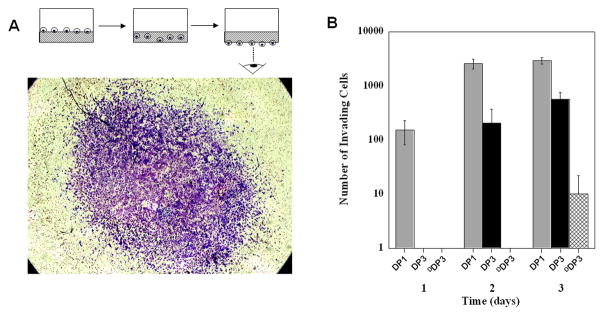

In vitro cell migration assays were then performed with DP1, DP3 and DDP3 peptide hydrogels using SW1353 cells that can be induced to express MMP-13. These three gels were chosen as models based on the data in Figure 2. If the ability of the cell to migrate through a given gel is, in part, dependent on the action of MMP-13, then a clear difference in migration rates should be observed using these gels. That is, cells should transverse the DP1 gel most easily, the DP3 gel less so, whereas migration through the DDP3 gel should be limited. Live/Dead assays were initially performed and confirm that all the gels are cytocompatible towards SW1353 cells, see Supporting Information. For the migration assays, DP hydrogels (0.5 wt%) were formed in a cell culture insert and cells were plated on top of the gels in the presence of 0.1% serum (v/v) in DMEM and IL-1β added to induce MMP-13 expression, Figure 5A diagram. Invasion was initiated by placing the inserts in 10% serum (v/v) containing media to establish a serum gradient across the gel. The ability of cells to migrate through a given peptide hydrogel to the bottom of the insert was quantified by staining and counting with the aid of an inverted microscope. Figure 5A shows a representative image of SW1353 cells that have migrated through a DP1 peptide hydrogel. Figure 5B shows the number of cells that have migrated through each gel as a function of time. The data show that a significant number of cells can migrate through the DP1 and DP3 gels in a time-dependent manner. Within one day, cells were capable of transversing the DP1 gel but not the DP3 nor the DDP3 gels. Only at day 2 have cells traversed the DP3 gel. At day 3, cells have migrated through all the gels, but only to a small extent for the DDP3 gel. The data in Figure 5B correspond well with the MMP-13 dependent rheological results shown in Figure 2A, suggesting that the cells are degrading the matrix in order to aid their migration. The rheological, analytical and cell based data together show that gels can be designed to control matrix degradation and the rate of cell migration into and through the gel.

Figure 5.

(A) In vitro invasion assay of SW1353 cells through 0.5 wt% DP1 hydrogel observed from the bottom of the transwell insert. (B) Number of cells that have traversed the DP1 (

), DP3 (■) or (⊠) DDP3 peptide hydrogel over a 3 day time period.

), DP3 (■) or (⊠) DDP3 peptide hydrogel over a 3 day time period.

In the context of wound healing, surrounding cells need to be able to degrade the provisional hydrogel to (i) invade the scaffold and (ii) to make room for new/native extracellular matrix and proliferating cells. The peptide gels described here fulfill these criteria largely as a result of their susceptibility to MMP-13. Although MMPs have proven useful to control material degradation of the DP gels, there are a plethora of other enzymes that can be exploited. Some other enzymes that have been implicated in tissue remodeling during wound healing are the kallikreins, cathepsin, ADAMs (a disintigrin and metalloproteinase), ADAMTSs (a distintigrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin motif) and the meprins to name a few [58, 59]. As new insight is gained concerning the roles these yet to be exploited proteases play in wound healing, their potential exploitation for biodegradable hydrogels should be considered.

Conclusions

Enzymatically catalyzed biodegradation, specific to MMP-13, was engineered into self-assembling β-hairpin peptide hydrogels. Proteolysis of the DP hydrogels by MMP-13 occurred in a time-, sequence-, and network morphology-dependent manner. Furthermore, the location of amide bond hydrolysis within each peptide sequence was well defined, as determined by LC-MS analysis. Although MMP-13 was able to readily degrade the DP hydrogels, MMP-3, another MMP expressed in damaged cartilage, showed limited effect, indicating that the gel networks display a preference towards MMP-13. In vitro assessment of SW1353 cell migration showed that cells can invade into and migrate through these gels. This work demonstrates that networks can be designed from self-assembling peptides that have tunable degradation profiles. In the context of wound healing, DP gels show potential as extracellular matricies for facilitating repair of damaged tissues that have elevated levels of MMP-13.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. I would personally like to thank Daphne A. Salick and Monica C. Branco for intellectual conversations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Drury JL, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24(24):4337–51. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fairman R, Akerfeldt KS. Peptides as novel smart materials. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15(4):453–63. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman AS. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopecek J, Yang JY. Hydrogels as smart biomaterials. Polym Int. 2007;56(9):1078–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(1):47–55. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicodemus GD, Bryant SJ. Cell encapsulation in biodegradable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14(2):149–65. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peppas NA, Hilt JZ, Khademhosseini A, Langer R. Hydrogels in biology and medicine: from molecular principles to bionanotechnology. Adv Mater. 2006;18(11):1345–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghunath J, Rollo J, Sales KM, Butler PE, Seifalian AM. Biomaterials and scaffold design: key to tissue-engineering cartilage. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2007;46:73–84. doi: 10.1042/BA20060134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajagopal K, Schneider JP. Self-assembling peptides and proteins for nanotechnological applications. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14(4):480–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Tomme SR, Storm G, Hennink WE. In situ gelling hydrogels for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Int J Pharm. 2008;355(1–2):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu L, Ding JD. Injectable hydrogels as unique biomedical materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37(8):1473–81. doi: 10.1039/b713009k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang SG. Emerging biological materials through molecular self-assembly. Biotechnol Adv. 2002;20(5–6):321–39. doi: 10.1016/s0734-9750(02)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woolfson DN, Ryadnov MG. Peptide-based fibrous biomaterials: some things old, new and borrowed. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10(6):559–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao Y, Yang ZM, Kuang Y, Ma ML, Li JY, Zhao F, et al. Enzyme-instructed self-assembly of peptide derivatives to form nanofibers and hydrogels. Biopolymers. 2010;94(1):19–31. doi: 10.1002/bip.21321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khetan S, Burdick JA. Patterning hydrogels in three dimensions towards controlling cellular interactions. Soft Matter. 2011;7(3):830–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seal BL, Otero TC, Panitch A. Polymeric biomaterials for tissue and organ regeneration. Mater Sci Eng: R: Rep. 2001;34(4–5):147–230. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopferich A. Mechanisms of polymer degradation and erosion. Biomaterials. 1996;17(2):103–14. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)85755-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh K, Clark RAF. Wound Repair. In: Lanza RP, Langer RS, Vacanti J, editors. Principles of tissue engineering. 3. Boston: Elsevier Academic Press; 2007. pp. 1149–1166. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woessner JF, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPS. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galler KM, Aulisa L, Regan KR, D’Souza RN, Hartgerink JD. Self-assembling multidomain peptide hydrogels: designed susceptibility to enzymatic cleavage allows enhanced cell migration and spreading. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(9):3217–23. doi: 10.1021/ja910481t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aimetti AA, Machen AJ, Anseth KS. Poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels formed by thiol-ene photopolymerization for enzyme-responsive protein delivery. Biomaterials. 2009;30(30):6048–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khelfallah NS, Decher G, Mesini PJ. Design, synthesis, and degradation studies of new enzymatically erodible poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate)/poly(ethylene oxide) hydrogels. Biointerphases. 2007;2(4):131–5. doi: 10.1116/1.2799034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shalaby WSW, Jackson R, Blevins WE, Park K. Synthesis of enzyme-digestible, interpenetrating hydrogel networks by gamma-irradiation. J Bioactive Compatible Polym. 1993;8(1):3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang JY, Jacobsen MT, Pan HZ, Kopecek J. Synthesis and characterization of enzymatically degradable PEG-based peptide-containing hydrogels. Macromol Biosci. 2010;10(4):445–54. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200900295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson J, Hubbell JA. SPARC-derived protease substrates to enhance the plasmin sensitivity of molecularly engineered PEG hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2011;32(5):1301–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patterson J, Hubbell JA. Enhanced proteolytic degradation of molecularly engineered PEG hydrogels in response to MMP-1 and MMP-2. Biomaterials. 2010;31(30):7836–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salinas CN, Anseth KS. The enhancement of chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by enzymatically regulated RGD functionalities. Biomaterials. 2008;29(15):2370–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrbar M, Rizzi SC, Schoenmakers RG, San Miguel B, Hubbell JA, Weber FE, et al. Biomolecular hydrogels formed and degraded via site-specific enzymatic reactions. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(10):3000–7. doi: 10.1021/bm070228f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levesque SG, Shoichet MS. Synthesis of enzyme-degradable, peptide-cross-linked dextran hydrogels. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18(3):874–85. doi: 10.1021/bc0602127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He XZ, Jabbari E. Material properties and cytocompatibility of injectable MMP degradable poly(lactide ethylene oxide fumarate) hydrogel as a carrier for marrow stromal cells. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(3):780–92. doi: 10.1021/bm060671a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss JA, Stokols S, Hixon MS, Ashley FT, Chang JY, Janda KD. Solid-phase synthesis and kinetic characterization of fluorogenic enzyme-degradable hydrogel cross-linkers. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(4):1011–6. doi: 10.1021/bm051001s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S, Chung EH, Gilbert M, Healy KE. Synthetic MMP-13 degradable ECMs based on poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-acrylic acid) semi-interpenetrating polymer networks. I. Degradation and cell migration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;75A(1):73–88. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chau Y, Luo Y, Cheung ACY, Nagai Y, Zhang SG, Kobler JB, et al. Incorporation of a matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive substrate into self-assembling peptides - a model for biofunctional scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29(11):1713–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J, Park Y, Tae G, Lee KB, Hwang SJ, Kim IS, et al. Synthesis and characterization of matrix metalloprotease sensitive-low molecular weight hyaluronic acid based hydrogels. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19(11):3311–8. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraehenbuehl TP, Ferreira LS, Zammaretti P, Hubbell JA, Langer R. Cell-responsive hydrogel for encapsulation of vascular cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30(26):4318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jun HW, Yuwono V, Paramonov SE, Hartgerink JD. Enzyme-mediated degradation of peptide-amphiphile nanofiber networks. Adv Mater. 2005;17(21):2612–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silver FH, Glasgold AI. Cartilage wound-healing - an overview. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1995;28(5):847–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunziker EB. Articular cartilage repair: problems and perspectives. Biorheology. 2000;37(1–2):163–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JH, Fitzgerald JB, Dimicco MA, Grodzinsky AJ. Mechanical injury of cartilage explants causes specific time-dependent changes in chondrocyte gene expression. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(8):2386–95. doi: 10.1002/art.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Overall CM. Molecular determinants of metalloproteinase substrate specificity - matrix metalloproteinase substrate binding domains, modules, and exosites. Mol Biotechnol. 2002;22(1):51–86. doi: 10.1385/MB:22:1:051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yucel T, Micklitsch CM, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Direct observation of early-time hydrogelation in beta-hairpin peptide self-assembly. Macromolecules. 2008;41(15):5763–72. doi: 10.1021/ma702840q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Branco MC, Nettesheim F, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP, Wagner NJ. Fast dynamics of semiflexible chain networks of self-assembled peptides. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(6):1374–80. doi: 10.1021/bm801396e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veerman C, Rajagopal K, Palla CS, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP, Furst EM. Gelation kinetics of beta-hairpin peptide hydrogel networks. Macromolecules. 2006;39(19):6608–14. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henriet P, Eeckhout Y. Collagenase. In: Barrett AJ, Rawlings ND, Woessner JF, editors. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. Vol. 3. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 486–494. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deng SJ, Bickett DM, Mitchell JL, Lambert MH, Blackburn RK, Carter HL, et al. Substrate specificity of human collagenase 3 assessed using a phage-displayed peptide library. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(40):31422–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004538200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lovejoy B, Welch AR, Carr S, Luong C, Broka C, Hendricks RT, et al. Crystal structures of MMP-1 and -13 reveal the structural basis for selectivity of collagenase inhibitors. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6(3):217–21. doi: 10.1038/6657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welgus HG, Grant GA, Sacchettini JC, Roswit WT, Jeffrey JJ. The gelatinolytic activity of rat uterus collagenase. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(25):3601–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagarkar RP, Schneider JP. Synthesis and primary characterization of self-assembled peptide-based hydrogels. Methods Mol Bio. 2008;474(1):61–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-480-3_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozbas B, Kretsinger J, Rajagopal K, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Salt-triggered peptide folding and consequent self-assembly into hydrogels with tunable modulus. Macromolecules. 2004;37(19):7331–7. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kretsinger JK, Haines LA, Ozbas B, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Cytocompatibility of self-assembled β-hairpin peptide hydrogel surfaces. Biomaterials. 2005;26(25):5177–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haines-Butterick L, Rajagopal K, Branco M, Salick D, Rughani R, Pilarz M, et al. Controlling hydrogelation kinetics by peptide design for three-dimensional encapsulation and injectable delivery of cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(19):7791–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701980104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salick DA, Kretsinger JK, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Inherent antibacterial activity of a peptide-based beta-hairpin hydrogel. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(47):14793–9. doi: 10.1021/ja076300z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Branco MC, Pochan DJ, Wagner NJ, Schneider JP. Macromolecular diffusion and release from self-assembled beta-hairpin peptide hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2009;30(7):1339–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Branco MC, Pochan DJ, Wagner NJ, Schneider JP. The effect of protein structure on their controlled release from an injectable peptide hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2010;31(36):9527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mackintosh FC, Kas J, Janmey PA. Elasticity of semiflexible biopolymer networks. Phys Rev Lett. 1995;75(24):4425–8. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.4425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ozbas B, Rajagopal K, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Semiflexible chain networks formed via self-assembly of beta-hairpin molecules. Phys Rev Lett. 2004:93. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.268106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niedzwiecki L, Teahan J, Harrison RK, Stein RL. Substrate-specificity of the human matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin and the development of continuous fluorometric assays. Biochemistry. 1992;31(50):12618–23. doi: 10.1021/bi00165a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nagase H, Fields CG, Fields GB. Design and characterization of a fluorogenic substrate selectively hydrolyzed by stromelysin-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-3) J Biol Chem. 1994;269(33):20952–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roycik MD, Fang X, Sang QX. A fresh prospect of extracellular matrix hydrolytic enzymes and their substrates. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(12):1295–308. doi: 10.2174/138161209787846676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moali C, Hulmes DJS. Extracellular and cell surface proteases in wound healing: new players are still emerging. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19(6):552–64. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2009.0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.