Abstract

Introduction

Ubiquinone (UQ) is a redox active lipid that transfers electrons from complex I or II to complex III in the electron transport chain (ETC). The long-lived C. elegans mutant clk-1 is unable to synthesize its native ubiquinone, and accumulates high amounts of its precursor, 5-demethoxyubiquinone-9 (DMQ9). In clk-1, complex I-III activity is inhibited while complex II-III activity is normal. We asked whether the complex I-III defect in clk-1 was caused by: 1) a defect in the ETC; 2) an inhibitory effect of DMQ9; or 3) a decreased amount of ubiquinone.

Methods

We extracted the endogenous quinones from wildtype (N2) and clk-1 mitochondria, replenished them with exogenous ubiquinones, and measured ETC activities.

Results

Replenishment of extracted mutant and wildtype mitochondria resulted in equal enzymatic activities for complex I-III and II-III ETC assays. Blue native gels showed that supercomplex formation was indistinguishable between clk-1 and N2. Addition of a pentane extract from clk-1 mitochondria containing DMQ9 to wildtype mitochondria specifically inhibited complex I-III activity. UQ in clk-1 mitochondria was oxidized compared to N2.

Discussion

Our results show that no measurable intrinsic ETC defect exists in clk-1 mitochondria. The data indicate that DMQ9 specifically inhibits electron transfer from complex I to ubiquinone.

Keywords: Mitochondria, longevity gene, C. elegans, aging, genetics, respiratory chain

1. Introduction

1.1 clk-1

The longevity of C. elegans clk-1 mutant animals remains an enigma, despite intensive efforts to understand its underlying causes. clk-1 was identified by Hekimi (Lakowski & Hekimi 1996; Ewbank et al. 1997) as the penultimate gene in the pathway synthesizing ubiquinone, a redox active lipid distributed in the membranes of eukaryotic cells (Crane 2007). One crucial function of UQ is to serve as a mobile electron carrier from complex I or II to complex III in mitochondria (Tran & Clarke 2007) (Supplemental Figure 1). Besides being an essential component of aerobic cellular respiration and ATP generation, UQ plays important roles in different biological processes. UQ acts as an antioxidant in its reduced form and eliminates lipid peroxyl radicals. Incompletely reduced UQ (semiubiquinone) acts as a pro-oxidant and can generate superoxide radicals (Genova et al. 2003; Sohal & Forster 2007). Deficiencies in CoQ cause a variety of clinical presentations, notably encephalomyopathy, cerebellar ataxia, myopathy, heart failure and infantile multisystemic disease (Quinzii et al. 2008; Quinzii & Hirano 2010; Fragaki et al. 2011). CoQ deficiency can also cause a mitochondrial deficiency syndrome through mitochondrial degradation (Rodriquez-Hernandez et al. 2009). Based on its crucial role in respiration and as an antioxidant, UQ is widely used as a therapeutic agent in treating mitochondria diseases (Marriage et al. 2004; Glover et al. 2010; Santa 2010), neurodegenerative diseases (Beal 2004; Earls et al. 2010) and cardiovascular diseases (Rosenfeldt et al. 2005; Yen et al. 2005; Sander et al. 2006; Molyneux et al. 2009).

Disruption of clk-1 or its homolog in mice (coq7) eliminates UQ synthesis and causes accumulation of the intermediate in UQ9 biosynthesis, 5-demethoxyubiquinone-9 (DMQ9) (Miyadera et al. 2001). clk-1 mutants in yeast (Padilla et al. 2004), C. elegans (Jonassen et al. 2001; Jonassen et al. 2002) and mice (Levavasseur et al. 2001) need UQ for normal development and survival. In nematodes, clk-1 animals are dependent on ingestion of bacteria producing UQ8 to replace the UQ9 normally synthesized by the worm (Jonassen et al. 2001); feeding clk-1 mutants UQ-less bacteria (GD1) results in larval lethality. Interestingly, loss of the enzyme COQ-3, a defect in UQ9 synthesis upstream of clk-1, is lethal, indicating that both exogenous UQ and endogenous DMQ9 are apparently necessary for survival of nematodes in the absence of UQ9 synthesis (Hihi et al. 2002). However, studies on the role of DMQ in respiration are conflicting. Several studies have concluded that DMQ cannot substitute for UQ in respiration and redox function in mitochondrial (Jonassen et al. 2001; Jonassen et al. 2002; Padilla et al. 2004) or non-mitochondrial sites (Hihi et al. 2002; Arroyo et al. 2006). Others have detected some activity of complex I-III (but not II-III) in the presence of DMQX (Wallace and Young 1977; Levavasseur et al. 2001, Miyadera et al. 2001; Miyadera et al. 2002). Investigations of other functions of DMQ showed that DMQ9 was unable to serve as an effective antioxidant for H2O2, though its ability to protect mitochondria from superoxide formation was not established. (Padilla et al. 2004)

1.2 Mitochondrial Function

We previously showed that mitochondrial complex I-dependent oxidative phosphorylation is inhibited in mitochondria from clk-1 nematodes, while succinate driven respiration is unchanged relative to wild type. In addition, the electron transport activity of CI-III is severely depressed while that of CII-III remains normal (Kayser et al. 2004b; Yang et al. 2009). Given the role of UQ in transporting electrons from both complexes I and II to complex III, this was a surprising finding. Moreover, clk-1 mitochondria containing UQ9, display similar decreases in complex I dependent respiration as those containing UQ8 (Yang et al. 2009). These mitochondria were obtained by feeding the clk-1 animals bacteria engineered to produce UQ9 (instead of UQ8). Therefore the decrease in I-III activity is not the result of the specific change from UQ9 to UQ8 as an electron transporter in clk-1 mutants. Whatever the cause of the complex I dependent defect, the result is an increase in ROS release in clk-1 animals (Yang et al. 2009; Lee et al., 2010). Recently, such an increase in ROS release has been implicated in extension of lifespan in C. elegans (Yang and Hekimi, 2010; Lee et al., 2010).

1.3 Quinones

Dietary supplementation of clk-1 animals with different UQs yielded relatively low amounts of exogenous UQs in clk-1 mitochondria (Yang et al. 2009); the overwhelmingly predominant UQ species in clk-1 mitochondria is, of course, DMQ9. Previous studies showed that complex I had a higher Km for ubiquinone than does complex II (Estornell et al. 1992; Lenaz 1998). As a result, the limiting amounts of exogenously supplied UQ available for electron transport in the clk-1 animal possibly affect I-III activity more than II-III activity. It also remains possible that DMQ9 competes with UQ specifically at complex I, but is less effective than UQ in electron transfer. This would result in DMQ9 being a functional inhibitor of electron transport from CI-III, but not from CII-III.

In addition, Nakai et al. reported that a coq7/clk-1 mutation in yeast led to disruption of mitochondrial structural integrity (Nakai et al. 2001). Loss of normal UQ9 in clk-1 mutants may interfere with formation or maintenance of intrinsic structures of the ETC including supercomplexes, which contain virtually all of the complex I found in C. elegans (Suthammarak et al. 2009). This distribution of complex I within supercomplexes may also limit the accessibility of any exogenously supplied quinones, i.e. quinones from the animal’s diet, to complex I. In turn, this difference in accessibility could give rise to the measured difference in Kms between complexes I and II for UQ.

We hypothesized that, if DMQ9 inhibited I-III activity, removing DMQ9 would eliminate the difference between N2 and clk-1 mitochondria. We studied the possible effects of DMQ9 by modifying a classic technique first described by Norling et al. (Norling et al. 1974). We extracted the endogenous quinones from wildtype and clk-1 mitochondria with pentane. UQ9 or UQ10 was added back to reconstitute enzymatically active mitochondria. If the DMQ9 is blocking electron transport in clk-1 mitochondria, or if the amount of UQ is critical for electron transport from complex I to complex III, then the restored electron transport activity in UQ-replenished clk-1 mitochondria will be the same as that in UQ-replenished N2 mitochondria. This finding then would also rule out that the ETC from clk-1 mitochondria is intrinsically defective, since replenishment of extracted mitochondria with UQ should not eliminate the difference between N2 and clk-1 I-III activity. We also studied the structure of supercomplexes in clk-1 mitochondria via blue native gels to interrogate native mitochondria for intrinsic structural differences.

To differentiate between inhibitory effects of DMQ9 and the effects of low ubiquinone concentrations we replenished N2 mitochondria with DMQ9 extracted from clk-1 mitochondria. Finally, we measured the redox status of UQ in N2 and clk-1 animals to determine if DMQ9 inhibits transfer of electrons from complex I to ubiquinone, or from ubiquinone to complex III. Our data indicate that DMQ9 specifically inhibits transfer of electrons from complex I to complex III.

2. Methods

2.1 Nematode strains

N2 (Bristol) and clk-1(qm30) were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (Minneapolis, MN, USA). clk-1(qm30) is the canonical null allele. Worms were grown on nematode growth media (NGM) agar with a lawn of E. coli as the food source, and maintained at 20°C. The engineered E. coli strains (Okada et al. 1997) used in this study were the kind gift of M. Kawamukai, Shimane University, Japan.

2.2 Pentane extraction

The experimental procedures were a modification of that published by Norling et al. (Norling et al. 1974). Mitochondria were first suspended in KME (100 mM KCl, 50 mM Mops, and 0.5 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) at 30 mg protein/mL and lyophilized for 8 hours. The lyophilized particles were suspended in cold pentane for 3 minutes with gentle homogenization. The pentane extract was removed by centrifugation (5100g, 5 minutes). To reconstitute UQ-depleted mitochondrial particles, the pellet was suspended with UQ9 or UQ10 (Sigma) in pentane at 40 nmol/g protein, shaken and incubated on ice for 5 minutes. The residual pentane and UQ were removed by centrifugation. UQ-depleted and UQ-replenished mitochondrial particles were dried under nitrogen and lyophilized for another hour to completely remove the pentane. UQ-depleted and UQ-replenished mitochondrial particles were rehydrated with KME for measurements of enzymatic activities. A portion of lyophilized mitochondria was rehydrated with KME, with no pentane extraction, as a control for maximal mitochondrial activity (L-mito in Figures).

DMQ9 used in replenishment of UQ-depleted mitochondria (E-N2) was pentane extracted from clk-1 mitochondria. 5mL of ice-cold pentane was added to 4mg of lyophilized clk-1 mitochondria. After a gentle homogenization on ice for 5 minutes, the pentane extract was separated from mitochondria particles by centrifugation (5125g, 5 minutes). The extract was dried under nitrogen gas and resuspended in 500 µL cold pentane. 40 pmole of UQ9 was added to the resuspended clk-1 extract. The mix was added to 1mg of UQ depleted-N2 mitochondria. The procedures for the remainder of the replenishment were as described above.

Normally worms are fed either E. coli K12 (growth in liquid culture) or E. coli OP50 (growth on agar plates), each of which produces UQ8. clk-1 mitochondria that were replenished with UQ9 were isolated from clk-1 grown on engineered bacteria producing UQ9 for at least two generations. Similarly, clk-1 mitochondria that were replenished with UQ10 were isolated from clk-1 grown on engineered bacteria producing UQ10. This was done in order to keep the primary ubiquinone species in the clk-1 mitochondria the same before extraction and after replenishment. Since N2 makes UQ9, and its complex I and II function is not altered by growth on wild type K12, or engineered UQ10-producing bacteria, or its UQ8 parental strain (Supplemental Figure 2), we fed N2 with K12 for these studies. For studies of the redox state of UQ in worms, N2 and clk-1 were grown on UQ9 engineered bacteria to minimize amounts of dietary UQ8.

2.3 UQ quantification and identification

The UQ species in lyophilized, UQ-depleted, and UQ-replenished N2 or clk-1 mitochondria were identified and quantified as described in Yang et al. (Yang et al. 2009). Samples were prepared by adding a known fixed amount of the internal standard di-propoxy-UQ10 (diPrQ10, a generous gift from Iain P. Hargreaves, Institute of Child Heath, London, United Kingdom) and 1-propanol (0.5mL for 400µg mitochondrial protein). 20µL of 2mg/mL p-benzoquinone were added to ensure that all the quinones were in the oxidized form. All the quinones (ubiquinones (UQ), demethoxyquinones (DMQ) and rhodoquinones (RQ)) were ionized by Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) and analyzed using a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Specific multiple reaction monitoring mode (MRM) transitions were performed, corresponding to m/z 864→197 (UQ10), 920→253 (diPrQ10), 795.5→197 (UQ9), 765.5→166.9 (DMQ9), 780.9→181.9 (RQ9), 727.5→197 (UQ8), 659.5→197 (UQ7) and 591.5→197 (UQ6), respectively. The samples were delivered to the API 4000 tandem mass spec (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) using an Agilent 1200 series HPLC binary pump (Agilent technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) delivering 50% methanol:isopropanol at 0.5mL/min in flow injection analysis (FIA) mode. Samples were quantified against a 6 concentration levels calibration curve made with known amounts of UQ6, UQ9 and UQ10 and the internal standard (diPrQ10) spanning the concentration range found in the samples. UQ7 was quantified assuming the same response in the detector as UQ6. UQ8, DMQ9 and RQ9 were quantified assuming the same response in the detector as UQ9.

Reduced (UQ9H2) and oxidized UQ9 ratios were assayed essentially as in (Ruiz-Jimenez et al. 2007) using a di-propoxy-CoQ10 internal standard prepared as in (Duncan et al. 2005). The fresh frozen worm pellets were extracted in 100% methanol, incubated in ice for 15 min and spun for 5 min at 13,000 g in a microfuge at room temperature. The protein content of the pellets was assayed with Coomassie Plus (Pierce, IL, USA). The supernatant was assayed for oxidized and reduced UQ9 levels after the addition of 120 ng/mL di-propoxy-UQ10 internal standard. A 5 µL aliquot of each sample was injected at 7°C in a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 µm particles) maintained at 45°C using a Waters Acquity UPLC system. Analytes were eluted at 0.8 mL/min flow rate with an isocratic separation using 2 mM ammonium formate in 100% methanol for a total cycle time of 3.5 minutes. clk-1 samples were assayed first and the reduced percentage was constant over the time of the assay. The effluent from the LC column was directly coupled to the electrospray source of a Waters Quattro Premier triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer running in positive ion mode. Identification and quantification of the analytes were carried out by monitoring the transition from the precursor to the product ions (multiple reaction monitoring mode, MRM). In particular the transitions of the precursor ions ammoniated adducts 812.6 m/z for UQ9 and 814.6 m/z for UQ9H2 to the product ion 197 m/z for both analytes (Ruiz-Jimenez et al. 2007) were monitored in parallel with the transition of the di-propoxy-UQ10 precursor ion 936.9 m/z to the product ion 253.2 m/z. Sample values of oxidized and reduced UQ9 were normalized to mg of protein.

2.4 Mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) assays

The electron transport activities of UQ-depleted and UQ-replenished mitochondrial particles were measured by ETC assays as described in Hoppel et al. (Hoppel et al. 1987). Complex I and I-III activities use NADH as an electron donor; complex II and II-III activities use succinate as an electron donor. Lyophilization and pentane extraction followed by UQ replenishment irreversibly inactivates a portion of the mitochondrial proteins. In order to arrive at meaningful numbers for electron transport in replenished mitochondria, we normalized ubiquinone dependent complex I-III activity to the ubiquinone independent NFR (NADH-ferricyanide reductase) activity. The ubiquinone dependent complex II-III activity was normalized to ubiquinone independent complex II activity. We then compared the normalized values for clk-1 mitochondria to those for N2 mitochondria treated in a similar fashion.

2.5 Blue Native Gels

Mitochondrial electron transport chain structures of N2 and clk-1 were analyzed by blue native gels following digitonin extraction as described previously. (Suthammarak et al. 2009; Suthammarak et al. 2010)

2.6 Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean of n experiments ± SD, with n ≥ 3. Data sets were individually compared using a student’s t-test. Two sets of data were considered as statistically different when p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 UQ replenished clk-1 mitochondria have similar activities as UQ replenished N2 mitochondria

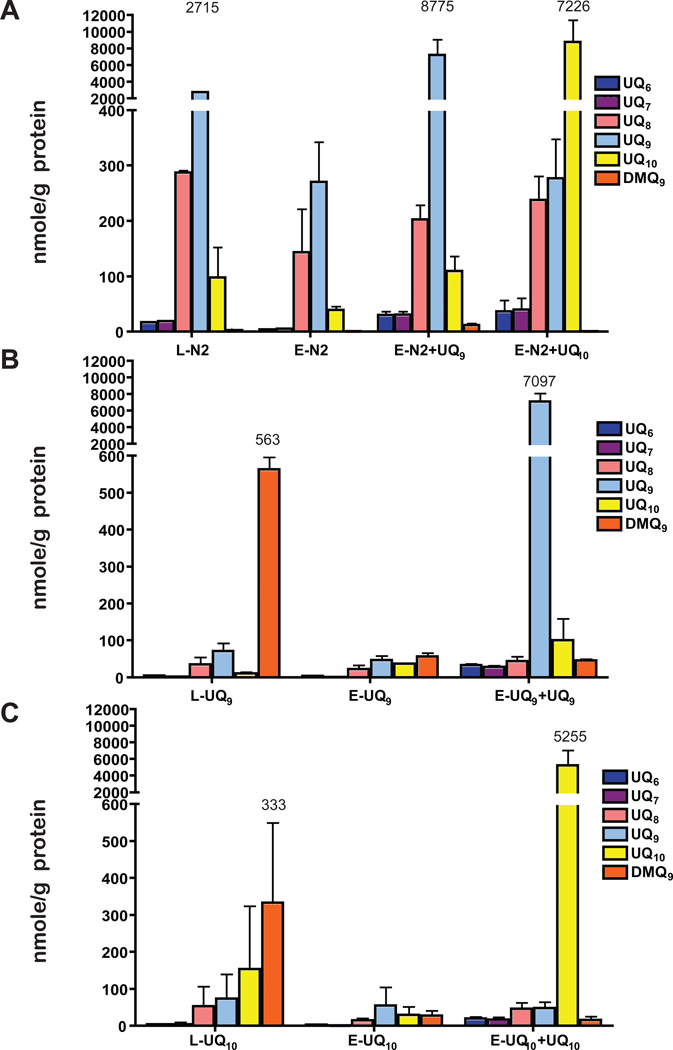

Before extraction, N2 mitochondria contained UQ9 (Figure 1A) at >2,000 nmole/gm of mitochondrial protein. clk-1 mitochondria contained DMQ9, and low amounts of UQ9 (Figure 1B,C). Following extraction, there were virtually no quinones in either clk-1 or N2 mitochondria, indicating that pentane effectively removed the endogenous quinones (E-N2 and E-clk-1 Figure 1A,B,C). Notably, essentially all DMQ9 was removed from the clk-1 mitochondria. After replenishment with specific UQs, both N2 and clk-1 mitochondria possessed equivalent amounts of UQ9 or UQ10 in concentrations greater than in N2 before extraction (Figure 1A, B, C).

Figure 1. The amount of UQ in pentane extracted/replenished N2 and clk-1 mitochondria.

(A) The amount of UQ measured in: L-N2 = lyophilized and rehydrated N2 mitochondria; E-N2 = pentane extracted N2 mitochondria; E-N2+UQ9 = pentane extracted N2 mitochondria reconstituted with UQ9. The majority of UQ measured in N2 mitochondria before extraction and after extraction and replenishment is UQ9. (B) The same experimental procedures were performed using mitochondria isolated from clk-1 grown on UQ9. The majority of UQ measured in clk-1 mitochondria before extraction is the biosynthetic precursor of UQ9, DMQ9. L-clk-1 = lyophilized and rehydrated mitochondria from clk-1 grown on UQ9. E-clk-1 = pentane extracted mitochondria from clk-1 grown on UQ9. E-clk-1+UQ9 = pentane extracted mitochondria from clk-1 grown on UQ9 replenished with UQ9(C) The same experimental procedures were performed using mitochondria isolated from clk-1 grown on UQ10. The majority of UQ measured in clk-1 mitochondria before extraction is the biosynthetic precursor of UQ9, DMQ9. L-clk-1 = lyophilized and rehydrated mitochondria from clk-1 grown on UQ10. E-clk-1 = pentane extracted mitochondria from clk-1 grown on UQ10. E-clk-1+UQ10 = pentane extracted mitochondria from clk-1 grown on UQ10 replenished with UQ10. Data shown here are means +/− standard deviation. Each sample was measured in duplicate from 3 – 5 independent pentane extraction/replenishment experiments. Numbers over largest peaks refer to the values (nmoles/g protein) of DMQX or UQX of the particular experiment and are added for clarification.

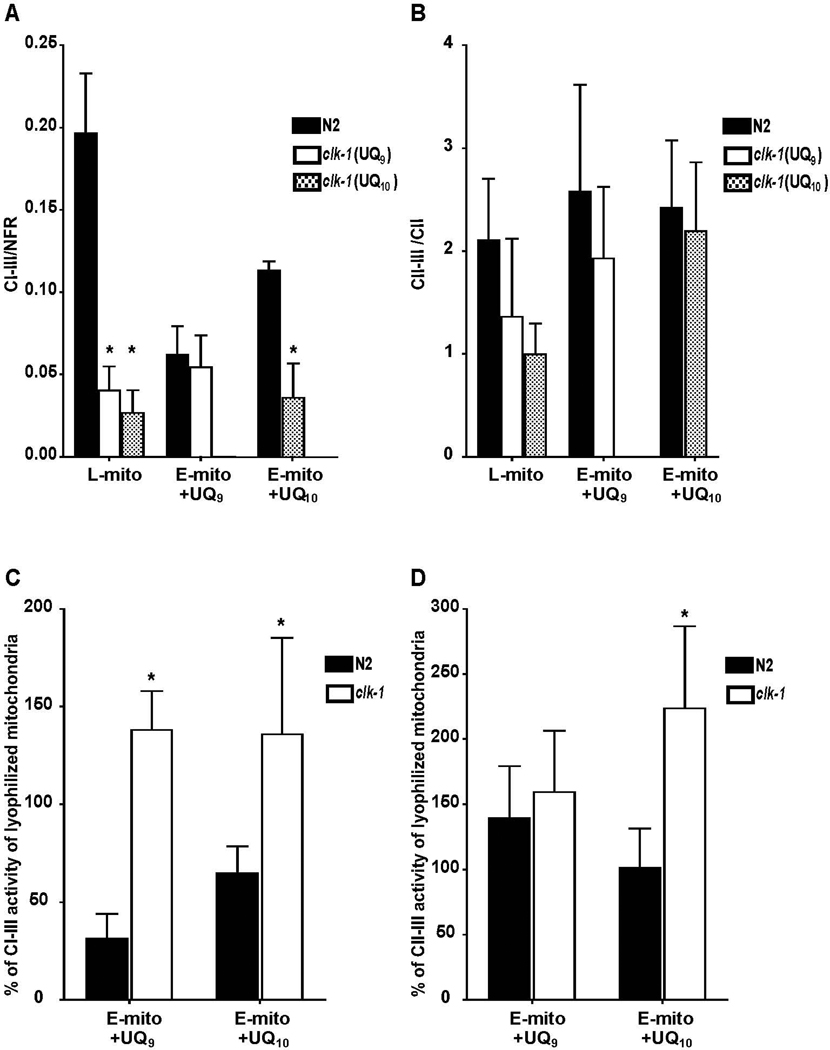

Simple lyophilization and rehydration of mitochondria from either N2 or clk-1 animals results in absolute I-III and II-III enzyme activities that are virtually identical to their activities prior to any treatment (Supplemental Table). We used this lyophilized and rehydrated activity (shown as L-mito in Fig. 2A and 2B) as our baseline activity since all extracted samples were subjected to these treatments. Since pentane extraction decreases the amounts of complex I and complex II present (as measured by NFR and complex II activities, respectively) we normalized all post extraction complex I-III results to NFR (the amount of remaining complex I) and complex II-III results to complex II activity (the amount of remaining complex II) in Figure 2. Pentane extraction unaccompanied by quinone replenishment nearly abolished complex I-III and complex II-III activities (Supplemental Figure 3). After extraction and replenishment with UQ9, the normalized activities (see above and Methods) of reconstituted clk-1 and N2 mitochondria were similar to each other (Figure 2A, +UQ9). This represented 130% of the activity of clk-1 mitochondria prior to extraction (Figure 2C), but only 30% of N2’s complex I-III activity prior to extraction. To determine whether I-III or II-III activities are dependent on the UQ species after this treatment, we also reconstituted N2 and clk-1 mitochondria with UQ10. I-III activity in N2 was higher than in clk-1 UQ10-replenished mitochondria (Figure 2A, +UQ10). This result suggests that either DMQ9 interferes with electron transport from complex I to III, or that the decreased amounts of ubiquinone ordinarily present in clk-1 mitochondria are limiting for complex I-III activity.

Figure 2. clk-1 mitochondria showed the same electron transport activities as N2 mitochondria after removing DMQ9.

After pentane extraction and replenishment with UQ9, activities of (A) complex I-III and (B) complex II-III were measured in N2 and clk-1 mitochondria. The activities were normalized to either NFR (for I-III) or CII (for II-III) activity. After pentane extraction and replenishment with UQ9, the normalized I-III (A) and II-III (B) activities showed no difference between clk-1 and N2 mitochondria. After replenishment with UQ10, N2 mitochondria had significantly higher activity complex I-III than clk-1 mitochondria. (C) Pentane extracted/replenished clk-1 mitochondria, regardless of whether they were replenished with UQ9 or UQ10, showed a greater percentage of recovery in complex I-III activity than did N2 when compared with lyophilized and rehydrated mitochondria (* indicates p < 0.05). (D) Pentane extracted clk-1 and N2 mitochondria replenished with UQ9 showed a similar percentage of recovery of compex II-III activity compared to lyophilized samples. clk-1 mitochondria replenished with UQ10 showed a greater proportional increase in II-III activity than did N2. Data shown here are means +/− standard deviations. Each sample was measured in duplicate from 4 – 7 pentane extraction/replenishment experiments. L-mito= lyophilized mitochondria. E-mito = pentane-extracted mitochondria. +UQ9 or +UQ10 refers to the ubiquinone used for replenishment.

Complex II-III activities were restored to normal levels in both N2 mitochondria and clk-1 mitochondria after pentane extraction and replenishment with UQ9 or UQ10 (Figure 2B, +UQ9, 2D, +UQ10). No relative improvement was seen in complex II-III activity in clk-1 mitochondria compared to N2 mitochondria with UQ9. Complex II-III activity of clk-1 mitochondria was greater when replenished with UQ10 compared with UQ9 (Figure 2D, +UQ10). This rate increase is similar to the increase in I-III activity with both UQ9 and UQ10. There was no increase in II-III activity when CoQ9 was used for the replenishment compared to the activity before pentane extraction. The cause of this difference is unclear, though it may indicate that UQ10 is a better substrate for nematode complex II than is UQ9.

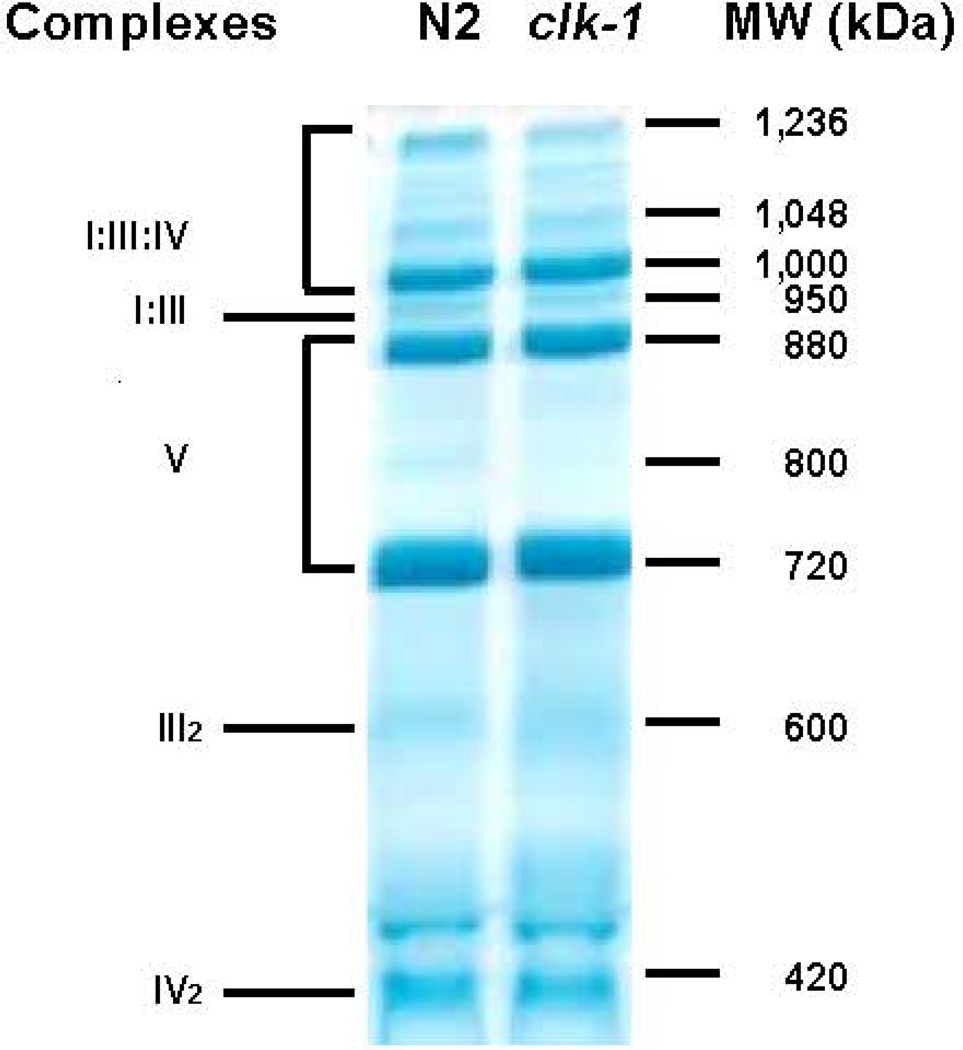

3.2 Blue Native Gels

Blue native gel analysis showed no differences between N2 and clk-1 mitochondria (Figure 3). In particular, the high molecular weight bands containing supercomplexes I:III:IV were identical between the two strains. Previous studies have shown that defects in complexes I, III, or IV can result in significant alterations in banding patterns of blue native gels (Falk et al. 2009; Suthammarak et al. 2009; Suthammarak et al. 2010).

Figure 3. The organization of respiratory complexes in N2 and clk-1.

Representative digitonin based blue native gel (from n=3 independent gels) of mitochondrial proteins from N2 and clk-1 as described in Suthammarak et.al. (Suthammarak et al. 2009). The numbers in the right panel indicate the approximate molecular masses (kDa) of the corresponding protein bands. On the left are the identities of the bands as determined by mass spectrometry in N2. (Suthammarak et al. 2009). No differences were noted between N2 and clk-1.

3.3 DMQ9 inhibits electron transport from complex I to UQ

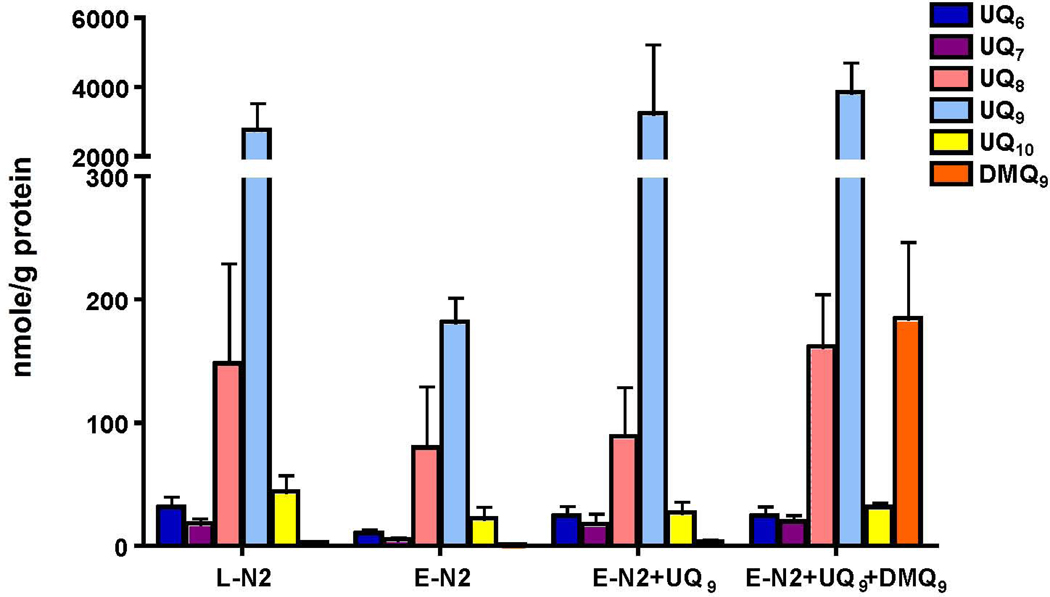

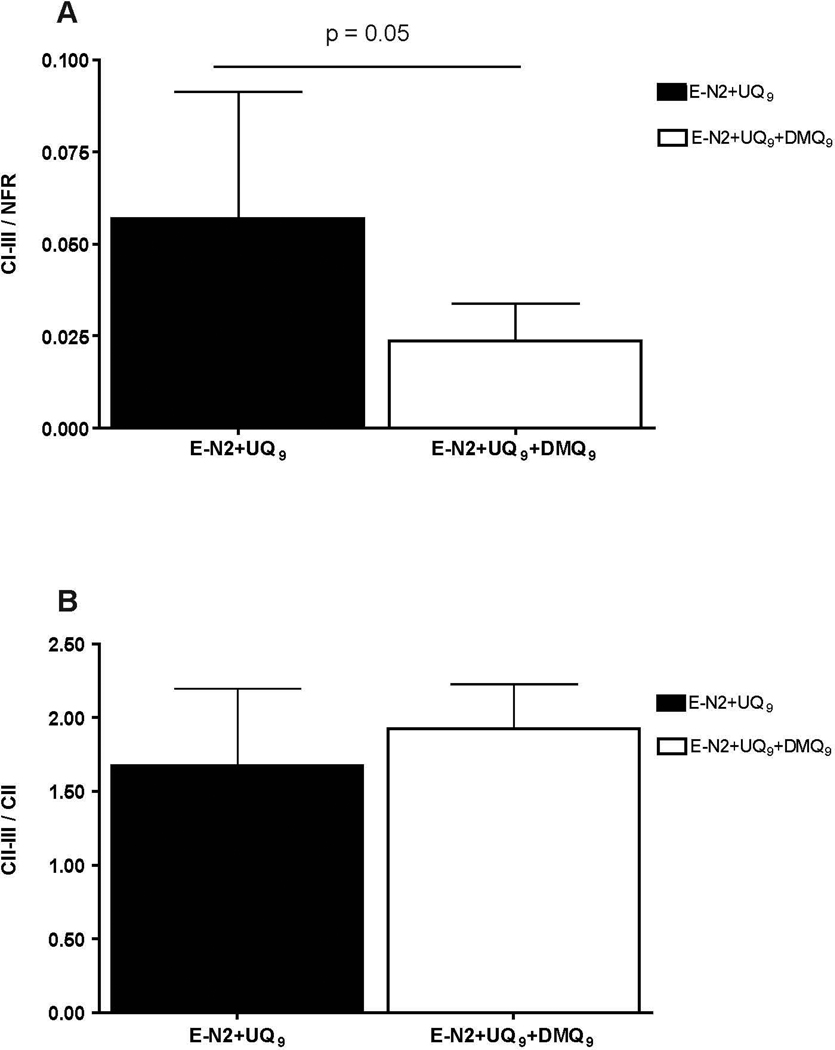

To investigate the effects of DMQ9 on electron transport, we added pentane extracts from clk-1 mitochondria (containing DMQ9) to UQ9. This mixture was used to replenish pentane extracted N2 mitochondria. The amounts of UQ9 in mitochondria replenished with either UQ9 alone or UQ9 plus DMQ9 were similar (Figure 4). However, the amount of DMQ9 in the replenished mitochondria was less than that normally found in clk-1 mitochondria (cf. Figure 1B with Figure 4). After normalizing complex I-III activity to NFR, a measure of complex I enzymatic activity in the preparation, the average I-III activitiy from mitochondria replenished with UQ9 and DMQ9 was decreased compared to UQ9-replenished N2 mitochondria (Figure 5A). Addition of a pentane extract from N2 mitochondria to UQ9-replenished N2 mitochondria did not decrease activity (Supplemental Figure 3). This result indicates that an extract from clk-1 mitochondria specifically inhibits complex I-III activity while an extract containing essentially UQ9 as its only quinone species does not. In contrast, the normalized complex II-III activity of UQ9-replenished mitochondria with or without DMQ9 are 1.9 and 1.6, respectively (Figure 5B), indicating that complex II-III activity was not significantly affected by the addition of DMQ9.

Figure 4. The quinone profile in mitochondria replenished with UQ9 and DMQ9.

DMQ9 was extracted from clk-1 mitochondria and added with UQ9 to pentane-extracted N2 mitochondria. Mitochondria incorporated DMQ9 along with UQ9. L-N2 = lyophilized N2 mitochondria. E-N2 = pentane-extracted N2 mitochondria. E-N2+UQ9 = pentane extracted N2 mitochondria reconstituted with UQ9. E-N2+UQ9+DMQ9 = pentane extracted N2 mitochondria reconstituted with UQ9 and DMQ9 extracted from clk-1 mitochondria.

Figure 5. Mitochondrial activities measured with or without DMQ9.

Complex I-III (A) and II-III (B) activities of UQ9-replenished mitochondria were measured with or without DMQ9 added to the replenishment mixture. The complex I-III and II-III activities shown here were normalized to NFR and CII activities, respectively. Complex I-III activity was decreased in the presence of DMQ9 (p = 0.05). Complex II-III activity was indistinguishable between mitochondria with or without DMQ9. Data shown here are mean +/− standard deviation. Each sample was measured in duplicate from 3 – 5 pentane extraction/replenishment experiments. E-N2+UQ9 = pentane extracted N2 mitochondria reconstituted with UQ9. E-N2+UQ9+DMQ9 = pentane extracted N2 mitochondria reconstituted with UQ9 and DMQ9 extracted from clk-1 mitochondria.

3.4 The percentage of reduced UQ9 is less in clk-1 than in N2

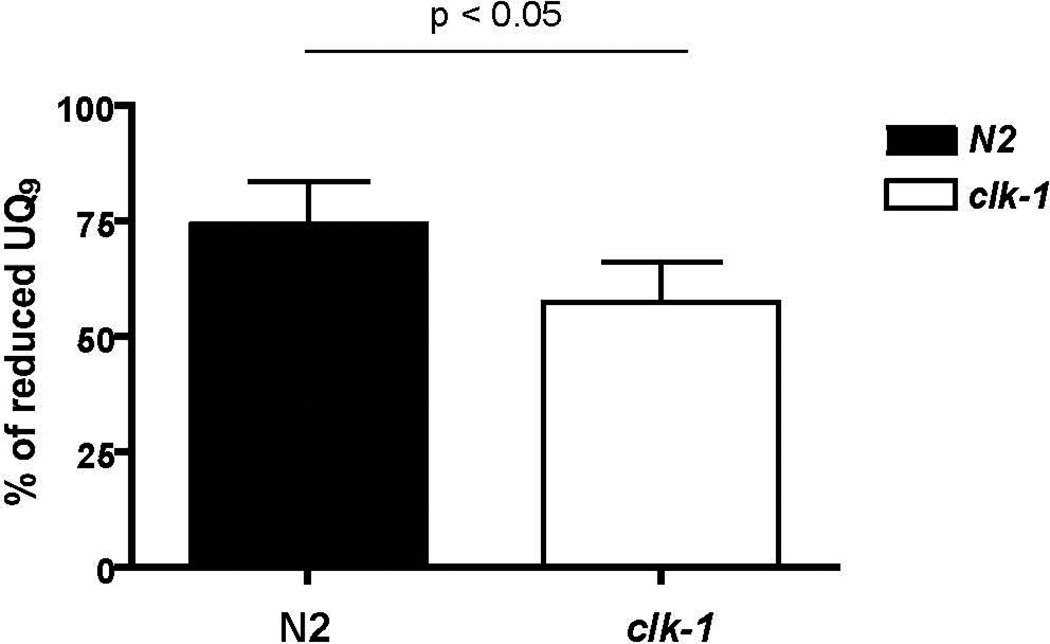

Previous work from whole worm extraction of UQ showed that a defect in complex I function in C. elegans led to a decrease in the reduced form of UQ, whereas a defect in complex III led to an increase in the amount of reduced UQ (Vasta et al. 2011). Thus, while preparations of UQ from whole worms include UQ from both inside and outside the mitochondria, clearly the assay can detect changes in UQ within mitochondria. We reasoned that if DMQ9 inhibits electron transfer from complex I to UQ, the percentage of reduced UQ in clk-1 animals will be decreased compared with that in N2. The percentage of reduced UQ in clk-1 and N2 worms, both fed with engineered bacteria producing UQ9, was measured in whole worms (Figure 6). The reduced UQ9 in N2 is 74.6 ± 9.1 % of the total UQ9. The reduced UQ9 in clk-1 is 57.7 ± 8.7% of the total UQ9 (p = 0.05). The decrease in the percentage of reduced UQ in clk-1 suggests that an inhibitor of electron transport from complex I to UQ exists in clk-1.

Figure 6. The percentage of reduced UQ9 is decreased in clk-1 compared with N2.

The percentage of reduced UQ9 was determined in clk-1 and N2 worms. The percentage of reduced UQ9 in the clk-1 mutant is 57.7 ± 8.7% of the total UQ, which is lower than that in N2 (74.6 ± 9.1 %, p < 0.05). Data shown here are means +/− standard deviations from 4–6 different worm cultures of N2 and clk-1.

4. Discussion

In this study, we sought to understand how complex I-III activity is deficient in clk-1 animals, while complex II-III activity is normal. There are several possible mechanisms for this phenomenon: 1) clk-1 mitochondria are intrinsically altered such that complex I-III activity is defective. 2) DMQ9 specifically inhibits the transfer of electrons from complex I to UQ or from UQ to complex III. 3) The levels of exogenous UQ exchanging with endogenous quinones within the supercomplex I:III:IV in clk-1 mitochondria are too low to support efficient electron transport. Transfer from complex II-III is less affected either because complex II has a lower Km for quinones (Estornell et al. 1992), or because the exogenous (i.e. bacterial) quinones can reach complex II more readily than complex I. In effect, a separate UQ pool may be available for complex I compared to complex II for exogenously supplied quinones (Estornell et al. 1992; Lenaz 1998). Any differences in exogenous UQ availability for transfer of electrons from complexes I versus II may in fact underlie the differences in ubiquinone related Kms between the complexes. Below we discuss each of these possibilities separately.

4.1 Intrinsic changes in clk-1 mitochondria

After pentane extraction of quinones from mitochondria, addition of UQ9 (or UQ10) restored complex I-III activity to similar levels in N2 and clk-1 mitochondria. This indicated that no initial differences existed between the ETC components per se that accounted for the difference in complex I-III activities between N2 and clk-1 mitochondria. However, we also sought corroboration from native preparations of mitochondria. Previous work suggested that clk-1 may actually affect mitochondrial structure (Nakai et al. 2001). We and others had already established that complex I activity may be significantly reduced when supercomplex I:III:IV formation is defective (Schafer et al. 2006; Suthammarak et al. 2009). Although isolated complex I activity is normal in clk-1 mitochondria (Kayser et al. 2004b), we wondered whether changes in supercomplex formation could explain the I-III defect. We found no apparent differences between N2 and clk-1 animals in supercomplex formation, in contrast to studies of the effects of defects in complexes I, III and IV (Falk et al. 2008; Suthammarak et al. 2009; Suthammarak et al. 2010).

4.2 Inhibition by DMQ9

The similar I-III activity in N2 and clk-1 mitochondria following removal of DMQ9 and replenishment with UQ is clearly consistent with an inhibitory effect of DMQ9 on the ETC. However, decreased amounts of functional ubiquinone in clk-1 mitochondria may also produce this effect. Ideally, kinetic studies with varying amounts of UQ to determine Vmax and Km values for UQ could resolve this dilemma. However, we are unable to titrate the amount of UQ in the I-III supercomplex to perform these experiments. Consequently, we can not assign DMQ as a classical competitive inhibitor for UQ. As an alternative approach to determine whether DMQ9 inhibits electron transport from complex I to III, it would be helpful to measure electron transport activity in reconstituted mitochondria that have equal amounts of DMQ9 and UQ9 present. Due to the unavailability of HPLC-purified DMQ9, this approach is also not technically feasible. Thus, we extracted the quinone species from clk-1 mitochondria (containing DMQ9) and replenished N2 mitochondria with the extract. Compared to N2 mitochondria replenished with UQ9 alone or with an N2 extract, we found that the addition of DMQ9 produced a lower complex I-III activity. Our data lend support to the studies that have previously found that DMQ does not substitute for UQ in respiration and redox function in the mitochondrial ETC (Jonassen et al. 2001; Padilla et al. 2004; Jonassen et al. 2002). It is possible that DMQ9 has limited electron transport activity and appears to inhibit UQ by competition for identical sites on complex I. It is also possible that an unidentified extracted compound in clk-1 mitochondria specifically inhibits complex I-III activity. However, this molecule must be specific to clk-1, since an N2 mitochondrial extract did not inhibit function.

DMQ9 could inhibit complex I-III activity either by blocking transfer of electrons from complex I to UQ9, or by interfering with the ability of UQ9 to pass electrons to complex III. To determine the location of the inhibition, we measured the percentage of reduced UQ in clk-1 animals. Vasta et al. previously identified the ratio of reduced and oxidized UQ in different C. elegans mitochondrial mutants (Vasta et al. 2011). In N2 grown on K12 bacteria UQ9 was 84% reduced. In isp-1, a mutant severely deficient in complex III function, 90% of UQ was in the reduced form. isp-1 contains a primary mutation in the Rieske iron-sulfur protein subunit of complex III (Feng et al. 2001). Furthermore, the complex I mutant gas-1 showed only 45% of total UQ in the reduced form; the complex II mutant mev-1 had 55% reduced UQ. Thus, the percentage of reduced UQ correlates with the location of the defect in the electron transport chain.

If DMQ9 interferes with the electron transport from complex I to UQ, a decrease in the percentage of UQ in the reduced form should be observed in clk-1 animals when compared with N2. Consistent with this model, the percentage of reduced UQ in clk-1 is lower than that in N2 animals. Of course, we are measuring UQ from extra-mitochondrial sources as well as from mitochondria. However, we have previously shown that with this technique we can unequivocally measure CoQ redox states that are consistent with the location of specific ETC defects (Vasta et al. 2011). Therefore, we think that a comparison of clk-1’s redox status to measurements in N2 gives accurate information about the location of clk-1’s ETC defect. In addition, DMQ9 may inhibit UQ reductases other than complex I or complex II. These potential targets include glutathione reductase, thioredoxin reductase and others (Turunen et al. 2004). However, given that other ETC defects gas-1 and mev-1 predictably decrease the percentage of reduced UQ9, we think that the most reasonable target for DMQ9 inhibition of I-III activity remains mitochondrial complex I. We conclude that DMQ9 inhibits the transfer of electrons from complex I to UQ9, as opposed to their subsequent transfer to complex III. Therefore, the defective complex I-III activity that has been observed in clk-1 mitochondria results at least in part from complex I-specific inhibitory effects of DMQ9.

4.3 Low levels of UQ

A limitation of our study is that we have not completely ruled out that the low levels of UQ in clk-1 mitochondria may contribute to the specific decrease in I-III activity compared to II-III activity. We interpret the redox status of UQ in clk-1 mitochondria to indicate that this possibility is less likely than inhibition of I-III function by DMQ9. However, it remains possible that the majority of dietary quinone in clk-1 mitochondria, or even replenished quinone, is excluded from the I:III:IV supercomplex, which is the predominant form of complex I in C. elegans (Suthammarak et al. 2009). Complex II, in nematodes, is not found as part of a supercomplex (Suthammarak et al. 2009), and therefore may be more accessible to exogenously supplied quinones. In addition, Lenaz earlier showed that the Km for reducing ubiquinone is 10 fold less for complex II than for complex I (Estornell et al. 1992; Lenaz 1998). Thus, the low amounts of UQ in clk-1 mitochondria are likely to affect complex I more than complex II. Since Lenaz determined the kinetics of quinone binding by adding quinones to mitochondria, the high Km of complex I for ubiquinone may also result from limited access of ubiquinones to complex I in the supercomplex. The decreased I-III activity of clk-1 mitochondria may be in part due to inhibition by DMQ9 as well as low amounts of UQ9 in the I:III:IV supercomplex. Dietary UQ may only be supporting complex II dependent respiration in clk-1 mitochondria. This may account for the decreased free radical damage ordinarily seen in clk-1 mitochondrial proteins (Yang et al. 2009), and perhaps underlies the basic CLK phenotypes.

Our results must be interpreted in light of the low total complex I-III activity regained in replenished mitochondria. This may represent either damage to the ETC by the pentane extraction or inadequate delivery of replenished quinone to the I:III:IV supercomplex. If damage, it appears also to be specific to complex I-III activity. Complex II, II-III, and NFR activities were very well maintained after replenishment, indicating that the mitochondria are not so extensively damaged as to eliminate other complex enzymatic functions. Regardless, damage should be the same in both N2 and clk-1 mitochondria. Therefore, comparison of these strains following UQ-replenishment is the most accurate measure of the effects of extracting DMQ9 available to us.

These results superficially conflict with a report by Branicky et al. (Branicky et al. 2006). They found a group of tRNA suppressors that improved many of the phenotypes of clk-1(e2519), including production of a normal number of offspring on Q-less bacteria. They concluded that the suppressed animals synthesized a small amount of UQ9, which they measured in extracts from whole worms grown on Q8-replete bacteria, OP50. They did not see any UQ9 in unsuppressed clk-1 animals grown on OP50. However, there are no data that show UQ9 synthesis from clk-1 animals grown on Q-less bacteria. We have measured similar amounts of UQ9 in mitochondria isolated from ordinary cultures of the null allele of clk-1(qm30) grown on UQ8-producing bacteria (Yang et al. 2009). In this case the UQ9 we measure in mitochondria must represent an exogenous contribution from their diet. We have in fact measured UQ9 in K12 and OP50 bacterial cultures (Yang et al. 2009). It is possible that the suppressors are working through effects other than restoring enzymatic activity of clk-1 animals. Regardless, the suppression did not significantly decrease levels of DMQ9 in whole worm extracts. They interpreted their results to indicate that DMQ9 did not contribute to the clk-1 phenotype. Nevertheless, our data are easily reconciled with that of Branicky et al., and in fact the sum of the data may give a clear picture of the role of exogenous versus endogenously supplied quinones. If the suppressed animals are in fact restoring clk-1 enzymatic activity, it may be that a small amount of endogenously synthesized UQ9 is sufficient to repair the Clk-1 phenotype, while exogenously supplied ubiquionone is not. We hypothesize that endogenous UQ9 can reach the I:III:IV supercomplex, while dietary UQ9 cannot. If this is the case, then endogenous UQ9 may out compete DMQ9 and allow I-III activity to be specifically rescued.

Our data lead us to conclude that a specific block of complex I activity is due to an inability of exogenous UQ from the diet to reach the I:III:IV supercomplex because limiting amounts of UQ cannot displace endogenous DMQ9, a poor electron carrier. If all endogenous quinones are extracted the clk-1 ETC can function as well as wildtype. DMQ9 specifically inhibits electron flow from complex I to complex III by blocking offloading of electrons from complex I to UQ.

4.4 Conclusions

Ultimately, studies of mitochondrial function in clk-1 animals must address whether the data can explain the animal’s longevity. Previously we reported that clk-1 mitochondria generated more ROS but accumulated remarkably less oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins (Yang et al. 2009). Moreover, the double mutant clk-1; gas-1 is extremely long-lived (Kayser et al. 2004a). gas-1 has complex I dependent rates of oxidative phosphorylation that are nearly identical to that of clk-1, but in contrast to clk-1, is very short lived and accumulates extensive oxidative damage (Kayser et al. 2001; Hartman et al. 2001). Since clk-1 reversed the short-lived phenotype of gas-1, and strongly decreases accumulated HNE damage, there is very likely an effective antioxidant in clk-1 worms. There are several possible candidates, though the sod genes seem to have been eliminated by the results of Yang (Yang et al. 2007). It is still possible that glutathione transferase, catalase, DMQ9 or another scavenger serve this role in clk-1. Although ROS production and damage do not always correlate with lifespan (Yang et al. 2007; Doonan et al. 2008), in clk-1 decreased electron transport through complex I is paired with increased ROS scavenging. This unique combination is the simplest explanation of the animal’s longevity. The decrease in complex I activity appears to be due to an inhibitory effect of DMQ9 on I-III activity.

Highlights.

> Complex I-III activity is defective in clk-1 mitochondria. > Removing DMQ9 from clk-1 mitochondria improves complex I activity. > Supercomplex structure is similar in N2 and clk-1. > DMQ9 inhibits complex I-III activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to Dr. Andrew Bauman and colleagues from Dr. Eugene Kolker’s laboratory for mass spectrometric analysis of our blue native gels. We thank Wichit Suthammarak for performing the blue native gels. We also appreciate the technical assistance of Ms. Toni Portman and Dr. Beatrice Predoi. MMS and PGM were supported for this work by NIH grants GM5881 and AG026073 and by American Recovery and Restoration Act Supplement 3R01GM58881-12S1. YY was partially supported NIH grant AG026073.

Abbreviations

- UQ

Ubiquinone

- DMQ

Demethoxyubiquinone

- C. elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans

- CI

complex I

- CII

complex II

- N2

wildtype C. elegans

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Institutions. All work was done at the institutions listed in affiliations.

Author Contributions. YY performed the replenishment, ETC and oxidative phosphorylation assays and helped write the manuscript. VV performed the redox status assays for ubiquinone. JG performed the assays of ubiquinone levels in the mitochondria. SH developed the redox status assays, designed and interpreted the results of those experiments. EO performed additional ETC and oxidative phosphorylation experiments requested by reviewers. PGM and MMS were involved in the design and interpretation of all aspects of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors were involved in editing the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yu-Ying Yang, Email: yyy4@uw.edu.

Valeria Vasta, Email: valeria.vasta@seattlechildrens.org.

Sihoun Hahn, Email: Sihoun.hahn@seattlechildrens.org.

Jon A. Gangoiti, Email: jgangoiti@ucsd.edu.

Elyce Opheim, Email: elyce.opheim@seattlechildrens.org.

Margaret M. Sedensky, Email: margaret.sedensky@seattlechildrens.org.

Phil G. Morgan, Email: pgm4@uw.edu.

References

- Arroyo A, Santos-Ocana C, Ruiz-Ferrer M, Padilla S, Gavilan A, Rodriguez-Aguilera JC, Navas P. Coenzyme Q is irreplaceable by demethoxy-coenzyme Q in plasma membrane of Caenorhabditis elegans. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1740–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases and coenzyme Q10 as a potential treatment. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2004;36:381–386. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041772.74810.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branicky R, Nguyen PAT, Hekimi S. Uncoupling the pleiotropic phenotypes of clk-1 with tRNA missense suppressors in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Bio. 2006;26:3976–3985. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3976-3985.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane FL. Discovery of ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) and an overview of function. Mitochondrion. 2007;7 Suppl:S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan R, McElwee JJ, Matthijssens F, Walker GA, Houthoofd K, Back P, Matscheski A, Vanfleteren JR, Gems D. Against the oxidative damage theory of aging: superoxide dismutases protect against oxidative stress but have little or no effect on lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3236–3241. doi: 10.1101/gad.504808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AJ, Heales SJ, Mills K, Eaton S, Land JM, Hargreaves IP. Determination of coenzyme Q10 status in blood mononuclear cells, skeletal muscle, and plasma by HPLC with di-propoxy-coenzyme Q10 as an internal standard. Clin Chem. 2005;51:2380–2382. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.054643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earls LR, Hacker ML, Watson JD, Miller DM., 3rd Coenzyme Q protects Caenorhabditis elegans GABA neurons from calcium-dependent degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14460–14465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910630107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estornell E, Fato R, Castelluccio C, Cavazzoni M, Parenti Castelli G, Lenaz G. Saturation kinetics of coenzyme Q in NADH and succinate oxidation in beef heart mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1992;311:107–109. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81378-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewbank JJ, Barnes TM, Lakowski B, Lussier M, Bussey H, Hekimi S. Structural and functional conservation of the Caenorhabditis elegans timing gene clk-1. Science. 1997;275:980–983. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk MJ, Rosenjack JR, Polyak E, Suthammarak W, Chen Z, Morgan PG, Sedensky MM. Subcomplex Ilambda specifically controls integrated mitochondrial functions in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2009;12:e6607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Bussiere F, Hekimi S. Mitochondrial electron transport is a key determinant of life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell. 2001;1:633–644. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragaki K, Cano A, Benoist JF, Rigal O, Chaussenot A, Rouzier C, Bannwarth S, Caruba C, Chabrol B, Paquis-Flucklinger V. Fatal heart failure associated with CoQ10 and multiple OXPHOS deficiency in a child with propionic acidemia. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:533–536. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genova ML, Pich MM, Biondi A, Bernacchia A, Falasca A, Bovina C, Formiggini G, Parenti Castelli G, Lenaz G. Mitochondrial production of oxygen radical species and the role of Coenzyme Q as an antioxidant. Exp Biol Med. 2003;228:506–513. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0322805-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover EI, Martin J, Maher A, Thornhill RE, Moran GR, Tarnopolsky MA. A randomized trial of coenzyme Q10 in mitochondrial disorders. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:739–748. doi: 10.1002/mus.21758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman PS, Ishii N, Kayser EB, Morgan PG, Sedensky MM. Mitochondrial Mutations Differentially Affect Aging, Mutability and Anesthetic Sensitivity in C. elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1187–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hihi AK, Gao Y, Hekimi S. Ubiquinone is necessary for Caenorhabditis elegans development at mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial sites. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2202–2206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppel CL, Kerr DS, Dahms B, Roessmann U. Deficiency of the reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase component of complex I of mitochondrial electron transport. Fatal infantile lactic acidosis and hypermetabolism with skeletal-cardiac myopathy and encephalopathy. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:71–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI113066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen T, Larsen PL, Clarke CF. A dietary source of coenzyme Q is essential for growth of long-lived Caenorhabditis elegans clk-1 mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:421–426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021337498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen T, Marbois BN, Faull KF, Clarke CF, Larsen PL. Development and fertility in Caenorhabditis elegans clk-1 mutants depend upon transport of dietary coenzyme Q8 to mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45020–45027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser EB, Morgan PG, Hoppel CL, Sedensky MM. Mitochondrial expression and function of GAS-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20551–20558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser EB, Morgan PG, Sedensky MM. Mitochondrial complex I function affects halothane sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Anesth. 2004a;101:365–372. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser EB, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is defective in the long-lived mutant clk-1. J Biol Chem. 2004b;279:54479–54486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowski B, Hekimi S. Determination of life-span in Caenorhabditis elegans by four clock genes. Science. 1996;272:1010–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S-J, Hwant AB, Kenyon C. Inhibition of respiration extends C. elegans life span via reactive oxygen species that increase HIF-1 activity. Curr Biol. 2010;20:2131–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaz G. Quinone specificity of complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1364:207–221. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levavasseur F, Miyadera H, Sirois J, Tremblay ML, Kita K, Shoubridge E, Hekimi S. Ubiquinone is necessary for mouse embryonic development but is not essential for mitochondrial respiration. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46160–46164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108980200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marriage BJ, Clandinin MT, Macdonald IM, Glerum DM. Cofactor treatment improves ATP synthetic capacity in patients with oxidative phosphorylation disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;81:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyadera H, Amino H, Hiraishi A, Taka H, Murayama K, Miyoshi H, Sakamoto K, Ishii N, Hekimi S, Kita K. Altered quinone biosynthesis in the long-lived clk-1 mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7713–7716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyadera H, Kano K, Miyoshi H, Ishii N, Hekimi S, Kita K. Quinones in long-lived clk-1 mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:33–37. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux SL, Florkowski CM, Richards AM, Lever M, Young HM, George PM. Coenzyme Q10; an adjunctive therapy for congestive heart failure? N Z Med J. 2009;122:74–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai D, Yuasa S, Takahashi M, Shimizu T, Asaumi S, Ksono K, Takao T, Suzuki Y, Kuroyanagi H, Hirokawa K, Koseki H, Shirsawa T. Mouse homologue of coq7/clk-1, longevity gene in Caenorhabditis elegans, is essential for Coenzyme Q synthesis, maintenance of mitochondrial integrity and neurogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2001;289:463–471. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norling B, Glazek E, Nelson BD, Ernster L. Studies with ubiquinone-depleted submitochondrial particles. Quantitative incorporation of small amounts of ubiquinone and its effects on the NADH and succinate oxidase activities. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47:475–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Minehira M, Zhu X, Suzuki K, Nakagawa T, Matsuda H, Kawamukai M. The ispB gene encoding octaprenyl diphosphate synthase is essential for growth of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3058–3060. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.3058-3060.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla S, Jonassen T, Jimenez-Hidalgo MA, Fernandez-Ayala DJ, Lopez-Lluch G, Marbois B, Navas P, Clarke CF, Santos-Ocana C. Demethoxy-Q, an intermediate of coenzyme Q biosynthesis, fails to support respiration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and lacks antioxidant activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25995–26004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinzii CM, Lopez LC, Naini A, DiMauro S, Hirano M. Human CoQ10 deficiencies. Biofactors. 2010;32:113–118. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520320113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinzii CM, Hirano M. Coenzyme Q and mitochondrial disease. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2010;16:183–188. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriquez-Hernandez A, Corder MD, Salviati L, Artuch R, Pineda M, Briones P, Gomez Izquierdo L, Cotan D, Navas P, Sanchez-Alcazar JA. Coenzyme Q deficiency triggers mitochondria degradation by mitophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5:19–32. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.1.7174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeldt F, Marasco S, Lyon W, Wowk M, Sheeran F, Bailey M, Esmore D, Davis B, Pick A, Rabinov M, Smith J, Nagley P, Pepe S. Coenzyme Q10 therapy before cardiac surgery improves mitochondrial function and in vitro contractility of myocardial tissue. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Jimenez J, Priego-Capote F, Mata-Granados JM, Quesada JM, Luque de Castro MD. Determination of the ubiquinol-10 and ubiquinone-10 (coenzyme Q10) in human serum by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry to evaluate the oxidative stress. J Chromatogr A. 2007;1175:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander S, Coleman CI, Patel AA, Kluger J, White CM. The impact of coenzyme Q10 on systolic function in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa KM. Treatment options for mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:1179–1196. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.11.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer E, Seelert H, Reifschneider NH, Krause F, Dencher NA, Vonck J. Architecture of active mammalian respiratory chain supercomplexes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15370–15375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal RS, Forster MJ. Coenzyme Q, oxidative stress and aging. Mitochondrion. 2007;7 Suppl:S103–S111. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthammarak W, Yang YY, Morgan PG, Sedensky MM. Complex I function is defective in complex IV-deficient Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6425–6435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805733200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthammarak W, Morgan PG, Sedensky MM. Mutations in mitochondrial complex III uniquely affect complex I in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40724–40731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran UC, Clarke CF. Endogenous synthesis of coenzyme Q in eukaryotes. Mitochondrion. 2007;7 Suppl:S62–S71. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G. Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1660:171–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasta V, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG, Hahn SH. Altered redox status of coenzyme Q9 reflects mitochondrial electron transport chain deficiencies in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:136–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BJ, Young IG. Aerobic respiration in mutants of Escherichia coli accumulating quinone analogues of ubiquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;461:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(77)90070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Li J, Hekimi S. A Measurable increase in oxidative damage due to reduction in superoxide detoxification fails to shorten the life span of long-lived mitochondrial mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2007;177:2063–2074. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Hekimi S. A mitochondrial superoxide signal triggers increased longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YY, Gangoiti JA, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG. The effect of different ubiquinones on lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen DH, Chan JY, Huang CI, Lee CH, Chan SH, Chang AY. Coenzyme Q10 confers cardiovascular protection against acute mevinphos intoxication by ameliorating bioenergetic failure and hypoxia in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat. Shock. 2005;23:353–359. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000156673.44063.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.