Abstract

The biological function of the Prion protein remains largely unknown but recent data revealed its implication in early zebrafish and mammalian embryogenesis. To gain further insight into its biological function, comparative transcriptomic analysis between FVB/N and FVB/N Prnp knockout mice was performed at early embryonic stages. RNAseq analysis revealed the differential expression of 73 and 263 genes at E6.5 and E7.5, respectively. The related metabolic pathways identified in this analysis partially overlap with those described in PrP1 and PrP2 knockdown zebrafish embryos and prion-infected mammalian brains and emphasize a potentially important role for the PrP family genes in early developmental processes.

Introduction

The Prion protein, PrP, has been the focus of intensive research for decades due to its pivotal role in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, a group of infectious neurodegenerative diseases of animal and human characterized by the accumulation of a pathological form of the protein (PrPSc) [1]–[3]. The physiological function of this ubiquitously expressed protein is still unclear. Various roles in neuroprotection, cellular homeostasis, response to oxidative stress, cell proliferation and differentiation, synaptic function and signal transduction have been proposed [4]–[7]. Even the sub-cellular localization of this glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol-anchored cell surface glycoprotein remains a subject of debate leading to yet other purported physiological processes involving PrP ([8] for exemple). The difficulty to define a role for this protein partially comes from the observation that Prnp-knockout mice [9], [10], cattle [11] and goat [12] suffer from no drastic developmental phenotype. Similarly, invalidation of this gene in adult mouse neurons does not affect the overall health of the mice [13], [14]. It has been hypothesized that another host-encoded protein is able to compensate for the lack of PrP [15] or, if not redundant, that PrP has no physiological function [16].

Comparative transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of adult brain from Prnp-knockout mice did not reveal drastic alterations if any [17], [18], supporting the above-mentioned hypothesis. A recent transcriptomic study performed on the hippocampus of wild-type and Prnp −/− new born (4–5 day-old) and adult (3 month-old) mice, revealed only a moderate alteration of the gene expression profile [19]. On the other hand, developmental regulation of the mouse Prnp gene suggested possible involvement of PrP in embryogenesis [20]–[23]. Its implication in hematopoietic [24], [25], mesenchymal [26], neural [27], cardiomyogenic [28] and embryonic [29], [30] stem cell proliferation, self-renewal and differentiation was also recently highlighted.

In zebrafish, the Prnp gene is duplicated and encodes proteins PrP1 or PrP2. PrP1 or PrP2 loss-of-function were found to be detrimental to zebrafish embryogenesis and survival [31]–[33]. Furthermore we found in a previous study that PrP and its paralog Shadoo are required for early mouse embryogenesis as embryonic lethality was observed at E10.5 in Sprn-knockdown, Prnp-knockout embryos [34].

Altogether, these data suggest that even though PrP knockout is not lethal, the physiological role of PrP may have to be investigated at early developmental stages rather than in adults, or in specific cell types such as adult stem cells. The aim of this study is to assess the potential transcriptomic incidence of Prnp-gene invalidation at early embryonic stages (6.5 and 7.5 dpc.).

Results and Discussion

Prnp-invalidation induces transcriptomic alterations at E6.5 and E7.5

Pools of FVB/N and FVB/N Prnp-knockout embryos were collected at E6.5 and E7.5 and their RNAs analyzed by RNAseq. These two developmental time-points were chosen according to the previously observed lethality in FVB/N Prnp-knockout, Sprn-knockdown embryos occurring before E10.5 [34] that was already substantial at E8.5, the gastrulation stage in mouse (BP and MV unpublished data). Seventy-three and 263 differentially expressed genes were detected between the two genotypes studied at E6.5 and E7.5, respectively (Table 1 and S2), representing 0.23 and 0.78% of total expressed genes. The majority of differentially regulated genes were under-expressed in Prnp-knockout versus wild-type embryos, 71.2 and 89.7% at E6.5 and E7.5, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of differentially expressed genes in Prnp-invalidated mouse embryos.

| E6.5 | E7.5 | |

| Total number of Differentially expressed genes | 73 | 263 |

| Up-regulated | 21 (28,76%) | 27 (10.2%) |

| >10 fold | 4 (5.47% of deregulated genes, 19.04% of up-regulated) LOC676933, Pax8, Mgat4c, Ptrf | 7 (2.66% of deregulated genes, 25.92% of up-regulated) Serpina1e, Napsa, Prss28, Prss29, NM_024283.2, Slco1a6, Prap1 |

| Down-regulated | 52 (71.23%) | 236 (89.7%) |

| >10 fold | 29 (39.72% of deregulated genes, 55.76% of down-regulated) Speer2, Fam186b, Rax, H2-M10.1, LOC633979, Magel2, LOC100046045, Cdh22, Myoz1, LOC100043825, Rmrp, Indol1, Scrt2, NM_175674.2, Dnajb5, Pcdh19, Mib2, LOC100046008, Scn3b, Rufy3, Stac3, Fam154b, EG666182, LOC633979, Hist4h4, Chsy3, XM_130735.7, LOC435145, Hmx2 | 47 (17.87% of deregulated genes, 19.91% of down-regulated) NM_177599.3, Msln, Hspb7, Kcnd3, Slpi, Tnfaip3, SecTm1b, Cst9, XM_001478533.1, Samd12, XR_032778.1, Corin, Havcr2, Ppp1r3c, Cyp2j11, Lsamp, Hsd11b1, Slc6a12, Lyve1, Ugt1a1, Cldn1, Emcn, Gpr115, Klk14, XR_034037.1, Anxa8, Psca, Lims2, Ly6Cc1, Ugt1a6b, Ly6c2, misc, Ly-6c, Pdzk1ip1, Tmem154, Ly6A, Tnfrsf11b, Gpr64, Lbp,Gpr115, Pglyrp1, Angpt4, Des, Tdo2, NM_172777.2, Dmkn, Alox5, |

Genes deregulated more than 10 fold are listed.

To be pointed out, the Prnp mRNA itself was not significantly differentially expressed at either E6.5 or E7.5. This observation is explained by the fact that the knocking out was performed by insertion of a neomycin-resistance gene within exon 3 of the Prnp locus [9]. The Prnp gene remains transcribed, although at an approximately 2-fold lower level as observed by Northern blotting and according to the RNAseq data (data not shown), but the resulting mRNA no longer encodes for PrP [9].

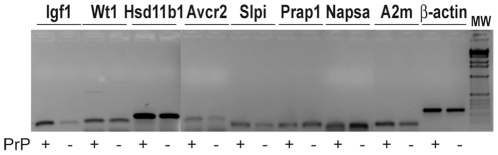

Ten genes were arbitrarily chosen for confirmation by RT-PCR. This was performed on E7.5 RNA samples different from those used for RNAseq experiments. The amplification signals obtained for the Ptrf and Prss28 transcripts were too low to be analyzed (data not shown). The RT-PCR analyses of the remaining 8 genes were congruent with the results obtained by RNAseq (Figure 1 and Table S2), confirming that comparative RNAseq analysis is a quantitative approach [35].

Figure 1. PCR analysis of differentially expressed genes.

Gel electrophoresis showing the amplification signals obtained by RT-PCR for 8 genes identified by RNAseq as being differentially expressed. The RT-PCR analyses of these 8 genes were congruent with the results obtained by RNAseq. Beta-actin was used as an internal control. PrP + and −: pools of E7.5 FVB/N and FVB.N Prnp-knockout embryo RNAs, respectively.

Twelve genes were differentially expressed at both embryonic stages of which 5 were consistently over-expressed in Prnp-knockout embryos (Table 2). Of note, these 5 genes, Prss28, Prss29, Napsa, MmP7 and XM_001477507.1, a transcript similar to that of ISP-2, share proteolysis activities and can modulate cellular adhesion and extracellular matrix deposition [36].

Table 2. Genes differentially expressed at both E7.5 and E6.5.

| Name | E7.5 (WT versus KO) | E6.5 (WT versus KO) |

| Ptrf | 0.120 | 13.726 |

| Rmrp | 4.18 | 9.153 |

| Napsa | 26.437 | 9.153 |

| 4933425M15 | 6.025 | 0.062 |

| Prss28 | 16.875 | 5.26 |

| Prss29 | 16.687 | 9.117 |

| Mib2 | 5.011 | 0.067 |

| LOC100047285 | 9 | 9.477 |

| Acvr1c | 3.401 | 0.181 |

| Mmp7 | 7.781 | 6.44 |

| Rpph1 | 3.087 | 0.114 |

| LOC677333 | 2.452 | 0.186 |

Numbers refer to fold change.

In silico analysis of the pathways affected by the observed transcriptomic alterations was undertaken to gain new insight into the biological function of PrP during mouse embryogenesis.

Convergence of Prnp-invalidation induced transcriptomic alterations between mouse and Danio rerio embryos

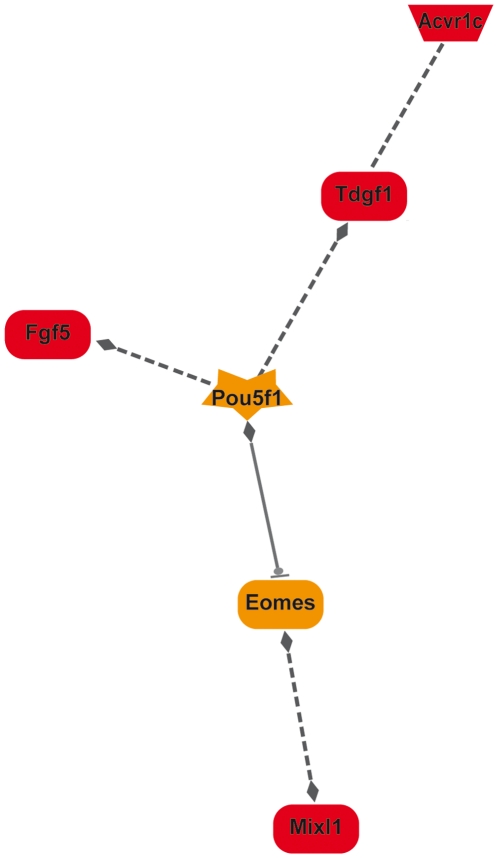

As mentioned above, 5 of the 12 genes that were differentially expressed at E6.5 and E7.5 were over-expressed in Prnp-knockout embryos and encode endopeptidases (Tables 2, 3 and S2). Mmp7 deregulation could be a consequence of the up-regulation of the Pax8 transcription factor at E6.5, as suggested by GEPS analysis (Figure 2), although to our knowledge a direct functional link between these two factors remains to be demonstrated. Endopeptidases can modulate the biological levels of cadherins and catenins and it was hypothesized that such induced alterations in cell-cell communication were at the origin of the arrested gastrulation observed in PrP1-depleted zebrafish embryos [31]. At E6.5, cadherin 22 and protocadherin 19 were indeed down-regulated in Prnp-knockout mouse embryos, suggesting an induced perturbation of cell movement [37], as described in zebrafish. Moreover, a correlation between lack of PrP and down-regulation of cadherins was recently described in the mouse hippocampus [19]. Modified cellular adhesion and cell proliferation pathways were detected at E7.5 (Table 3) [36], [38]. These networks highlight potential key regulatory roles of the growth factor Fgf5, Igf1 and Tdgf1 proteins, expression of which was significantly modified in the absence of PrP (Supplementary data Table S2 and data not shown). Biological links between some of these proteins and PrPc have already being described in adult tissues [39]–[41]. However, their modified expression could be indirectly linked to that of PrP, and induced by overexpression of Pou5f1 (Figure 3). This transcription factor is up-regulated in Prnp-knockout E7.5 embryos (Table S2) and has been associated with FGF5 and TDFG1 gene regulation [42], [43]. Expression of Pou5f1 and PrP was recently found to be correlated in differentiating mouse ES cells [30]. The Igf1 deregulation might be a consequence of the observed deregulation of Wt1 ([44] and Table S2), although the link between the Wt1 transcription factor and Igf1 regulation remains hypothetical. On the other hand, the up-regulation of Fgf5 could have in turn down-regulated that of Igf1 in the absence of PrP, as already observed [39]. Thus, the Prnp-knockout induced deregulation of Pou5f1 might be the trouble spot at the origin of these networks (Figure 3).

Table 3. Summary of the highest represented functional groups of genes from the differentially expressed gene list at E7.5.

| Category | Genes | Nb of genes |

| Proteolysis | Prss28,Prss29,Napsa,Mmp7,XM_001477507.1(similar to ISP-2),Ctsk,Ctso | 7 |

| Protease inhibition | Slpi,Cst9,A2m,Serpina1e | 4 |

| Biological adhesion | Igfbp7,Angpt2,Smoc2,Epdr1,Sned1,Igsf11,Nrcam,Lsamp,Thy1,Adam12,Cd36, Cd34,Lamb2,Gpnmb,Tdgf1,Fbln2,Msln,Lyve1,Cldn1,Cldn5 | 20 |

| Nervous system development | Igf1,Fgf5,Bdnf,Apob,Aqp1,Sgk1,Bmp2,Atoh8,Tgfbr2,Cldn5,Cldn1,Gja1,Thy1, Eomes,Ednrb,Mt3,Tacc1,Hoxd10,Hdac9,Nrcam,Corin,Mal,Lamb2 | 23 |

| Apoptosis | Tnfrsf11b,Igf1,Bdnf,Ednrb,Bmp2,Irak3,Tlr4,Pglyrp1,Pmaip1,Casp12,Tnfaip3, Gja1,Sgk1,Wt1,Srgn,Acvr1c,Anxa1,Cryab,Cryaa,Mal | 20 |

| Cell proliferation | Fgf5,Igf1,Bdnf,Ednrb,Lgr4,Tgfbr2,Tlr4,Ptges,Acvr1c,Fosl2;Bmp2 Ptgs1,Gja1,Mmp7,Nampt,Sat1,Anxa1,Pmaip1,Tdgf1,Tacc1 | 20 |

| Inflammatory and innate immune response | Tlr4,Serping1,Cd55,Bmp2,Tlr3,Lbp,Alox5,Ggt5,Anxa1,Hdac9,Cd36,Pglyrp1,Irak3 | 13 |

| Heart formation and blood vessel development | Apob,Cd36,Igf1,Wt1,Angpt2,Tgfbr2,Gja1,Tdgf1,Thy1,Cdx4,Tnfaip2 | 11 |

| Vascular diseases | Atp8b1,Ugt1a1,Slco1a6,Rgs5,Tnfaip2,Rgs2,Nrcam,Pmaip1,Lsamp,Pou5f1,Mixl, Tdgf1,Casp12,Lbp,Havcr2,Tlr4,Irak3,Tlr3,Fstl1,Add3,Ptn,Fgf5,Penk,Mt3,Bdnf, Tgfbr2,Fbln2,Fbn1,Mfap5,Col5a2,Dcn,Lum,Ramp3,Sparcl1,Timp3,Ednrb,Gpx3, Adam12,Abp1,Mgp,Bmp2,Fosl2,Vsig2,Cyp11b1,Igfbp7,Nampt,Sat1,Angpt2,Slpi, Igf1,Alox5,Anxa1,S100a4,Pglyrp1,Ptgs1,Ptges,Tnfaip3,Hdac9,Hsd11b1,Slc2a12,Srgn, Apob,Vldlr,Cd36,Tnfrsf11b,Ctsk,Cxcl14,Sgk1,Srd5a1,Bche,Gda,Abat,A2m,Gja1,Des,Dtna, Cryab,Cd34,Il6ra,Abcd1,Hoxa10,Sfrp4,Sfrp5,Dkk2,Wt1,Tacc1,Cldn1,Cldn10a,Cldn5, Lyve1,Emcn,Thy1,Cd55,Aqp1,Serping1,Ly6a,Ly6c1,Ly6c2,Gpihbp1 | 99 |

| Response to oxidative stress | Gpx3,Tlr4,Ptgs1,Anxa1,Cryab,Cryaa | 6 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase | Angpt2,Slpi,Igf1,Timp3,Tlr4,Rgs2,Irak3,Ptges,Alox5,S100a4,Adam12,Mmp7, Aqp1,Nampt,Wt1,Hoxa11,Bmp2,Tgfbr2,Bdnf,Fosl2,Jam2,Cldn5,Tnfrsf11b | 23 |

| Prion disease | Bdnf,Igf1,Dcn,Bche,Tgfbr2,Srgn,Aqp1,Cd34,Thy1,Ly6a,Cryab,Anxa1,Ptgs1, Alox5,Tlr3,Tlr4,Casp12,Mt3 | 18 |

UP-regulated genes are in bold type.

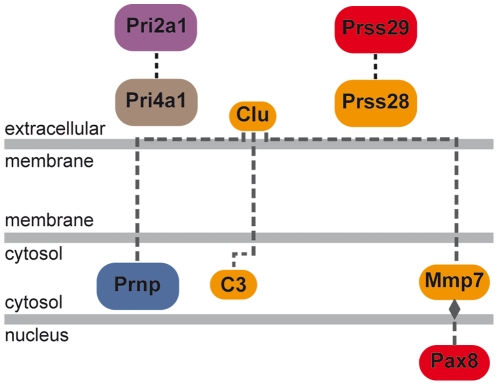

Figure 2. Differentially expressed gene pathway at E6.5 linking Pax8 and Mmp7.

A pathway was generated by the GEPS program from Genomatix that connects differentially expressed genes found at E6.5. It suggests a modulation of the matrix metalloprotease Mmp7 by PAX8. (See Figure S2 for detailed Genomatix network legend).

Figure 3. Pou5f1 could modulate expression of other observed key factors at E7.5.

A GEPS network connecting the up-regulated genes at E7.5 was detected. It shows a potential regulation by Pou5f1 of the over-expressed key regulatory factors. (see Figure S2 for detailed genomatix network legend).

At E7.5, the relative over-expression levels of Prss28, Prss29, Napsa, MmP7 and XM_001477507.1 in Prnp-knockout embryos were significantly elevated compared to those observed at E6.5 (Table 2 and S2). Protease inhibitors such as Slpi, Cst9, A2m were also down regulated at this stage, which could increase the activity of matrix metalloproteases [45], [46], while Serpina1e expression was highly elevated. However, Pax8 up-regulation was not in evidence at E7.5, neither were cadherin 22 and protocadherin 19 down-regulations, which might reflect an adaptation of the embryonic metabolism.

Overall, this transcriptomic analysis reveals a striking biological convergence between the PrP-knockout induced deregulation in early mouse embryos and that previously described in PrP1-invalidated zebrafish eggs [31]. The resulting outcome is not lethal in the mouse which, according to the results published by us [34], suggests a sufficient compensatory mechanism by the related Shadoo protein to the absence of PrP that sustains the embryonic development. So far, the developmental regulation of the Sprn gene and the biological properties of the protein have not yet been described in zebrafish. Such investigations could indirectly validate this hypothesis.

Invalidation of the later developmentally regulated PrP2-encoding zebrafish gene led to impaired brain and neuronal development [32]. Although it is reminiscent of the phenotype observed in the surviving mouse Prnp-knockout, Sprn-knockdown embryos [34], such phenotype has not been described for mammalian Prnp-knockout embryos. However, our transcriptomic analysis also highlights alterations of specific networks involved in nervous system development in the Prnp-knockout mouse embryos, as described below.

The transcriptomic alteration in Prnp-invalidated mouse embryos evokes a negative image of that found in prion-diseased brains

Although prion-associated pathologies have been extensively studied, with detailed descriptions of the associated neuropathology, the underlying mechanism leading to neurodegeneration is still poorly understood ([47] for review). Among the existing debate is the question whether this pathology results from a PrP loss-of-function, a PrPsc gain-of-function, a subversion of PrP function by PrPSC or a combination of these three mechanisms [48]. The simple PrP loss-of-function hypothesis was not sustained by the observation of the limited and subtle phenotypes resulting from the gene invalidation in mammals [9]–[12].

Differentially expressed genes in prion-infected adult mouse brains have been identified by microarray analyses [49]–[51]. Although strain-specific responses were detected leading to some gene specificity, overall similar biological functions were highlighted in all experiments, such as cell growth and adhesion, proteolysis, protease inhibition, response to oxidative stress, inflammation, immune response, cell death and neurological disorders. In each of the identified pathways, genes that were also differentially expressed in our study were described. Indeed, similar biological networks were identified by Ingenuity and Genomatix analyses (Table 3). We have already mentioned specific pathways involving cell proliferation and adhesion as well as differentially expressed proteases and anti-proteases that distinguish Prnp-knockout embryos from their wild-type counterparts (Table 3). At E7.5, matrix metalloprotease, apoptosis, inflammatory response and response to oxidative stress networks were also revealed by in silico analyses. Two genes appear to be central to these networks, Igf1 and Tlr4 (Figure S1). As mentioned previously, deregulation of Igf1 has previously been observed in relation with PrP [39]. Invalidation of Tlr4 resulted in accelerated prion disease pathogenesis in transgenic mice [52], a result attributed to a modulation of the innate immune system response. Our data would suggest that PrP expression per se has a role in immune function in the absence of pathogenic prion.

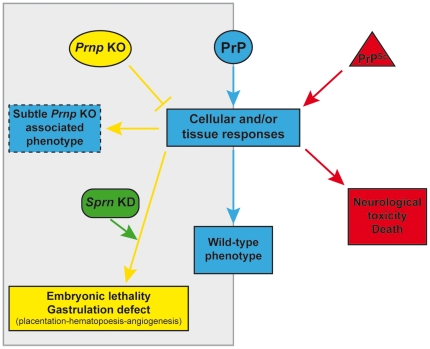

Most of the differentially expressed genes were reported to be up-regulated in prion affected adult brains while they are down-regulated in Prnp-knockout embryos. For example, the up-regulation of Cathepsins, a family of lysosomal proteases, has been associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's and prion diseases [49]. In contrast, our results demonstrate a down-regulation of Cathepsins in the absence of PrP. Overall; this observation suggests that the prion disease pathology does not mimic a PrP-lack of function. On the contrary, it seems that in the presence of infectious prions, the activated cellular or tissue response is a negative of that observed in the absence of PrP, suggesting that prions over-activate the normal PrP protein signaling, leading to neurotoxicity. This hypothesis may also relate to the observed down-regulation of the Shadoo protein in terminally prion-affected mouse brains. In zebrafish, this mirror effect would lead to embryonic lethality in the absence of either PrP1 or PrP2, while in mammals, a host-encoded protein, probably Shadoo [34], might allow for sufficient compensatory mechanisms to take place to sustain embryonic development (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Schematic presentation of the mirror effect hypothesis.

The activated cellular and/or tissue response in the presence of PrPSc (right side) is a negative image of that observed in the absence of PrP (left side). It suggests a mechanism of prion disease associated neurodegeneration in which the over activation or subversion (Harris and True, 2006) of PrP by PrPSc could lead to neurotoxicity. In Prnp knockout mice, the presence of the protein shadoo seems to be essential for an efficient compensatory mechanism and survival. In Prnp-knockout, Sprn-knockdown mice, an embryonic lethality was observed, this lethality could be caused by a gastrulation defect characterized by placentation and hematopoesis defaults.

Prnp-invalidation induced transcriptomic alterations are consistent with a putative role of PrP during early embryogenesis

Invalidation of PrP induces transcriptomic alterations that can be related to several developmental processes. At E6.5, deregulation of transcription and chromatin-related biological process were detected, as exemplified by the down-regulation of various histone cluster genes in Prnp-knockout embryos (Table S2), possibly reflecting the above-mentioned perturbation of the cell proliferation process. It further highlighted the implication of PrP in the self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells [27], [29], [30]. Similarly, specific networks related to the development of the nervous system were detected (Table 3), further emphasizing the neuro-specificity of PrP signaling [7], as well as with other developmental processes such as odontoblastic/osteogenic and muscle development.

Our analysis pointed towards a major pathway involved in cardiovascular development, hematopoiesis and angiogenesis, with the identification of specific networks including vascular diseases, arteriosclerosis, blood vessel development and morphogenesis (Table 3 and data not shown). PrP has recently been shown to identify bipotential cardiomyogenic progenitors [28] and to be involved in the self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells [24]. Its absence in Prnp-knockout embryos negatively affects the expression of Mesp1 (Supplementary data Table S2), a gene associated with the earliest signs of cardiovascular development [53], potentially capable of generating the multipotent cardiovascular progenitors and involved in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition [54]. Prnp-knockout embryos also had reduced expression of Timp-3, a gene that expands the multipotent hematopoietic progenitor pool [55], and that of Hoxa10, a gene also involved in this process [25]. Prnp invalidation increased the expression of the MixL1 transcription factor, capable of suppressing hematopoietic mesoderm formation and promoting endoderm formation [56], and that of TDGF1 that inhibits cell differentiation [57] (Figure 3). Finally, the absence of PrP also negatively affects the expression of various G protein-coupled receptors and doing so angiogenesis [58].

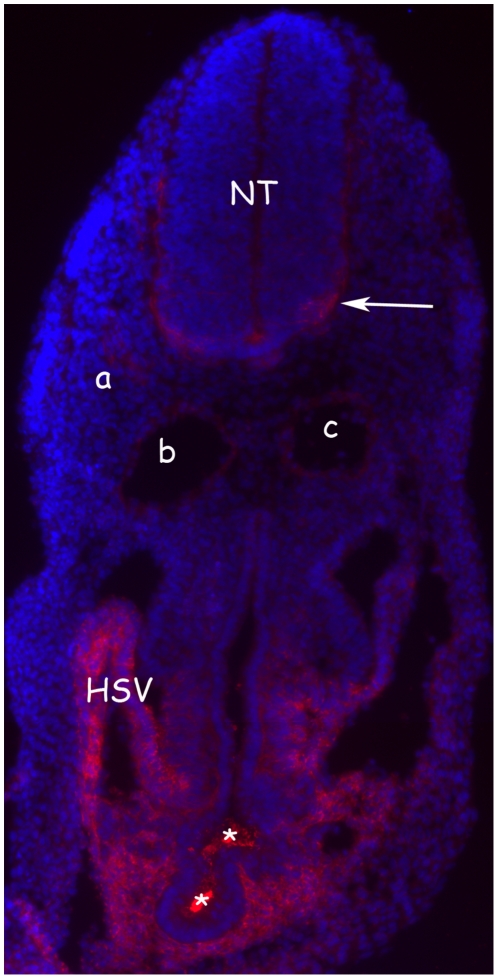

These findings raise the question if and to what extent PrP is expressed in the cardiovascular system of the early embryo. Immunochemistry analysis could not be performed at E7.5 for technical reasons (see materials and methods). At E9.5, however, it revealed expression of PrP in the developing heart, as previously described using PrP-LacZ transgenic mice [22], with a particularly intense signal in the region of the sinus venosus, a part of the embryonic cardiovascular system draining the blood flow into the heart (the venous pole) (Figure 5). Interestingly, expression pattern of PrP in this region is reminiscent of that of Islet1, a transcription factor gene expressed by cardiogenic progenitors [59]. In addition, PrP expression was detected in the endothelium of blood vessels such as the dorsal aortas. Worthy of note, PrP expression in the cardiovascular system was of comparable intensity to that visible in the nervous system, especially the developing neural tube (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Expression of PrP in the embryo.

At E9.5, PrP expression was observed in endothelial cells of blood vessels (a), including dorsal aortas (b, c) and in the developing heart with, as shown in this figure, a very intense signal observed in the sinus venosus. The saturated signal visible here (asterisk) is artefactual. HSV: horn of the sinus venosus. At E9.5, PrP expression in the nervous system is mainly detected in the lateral part of the neural tube (NT), the mantle zone (arrow): this zone is formed by cells undergoing differentiation that have migrated from the medial part of the neural tube where cells continue to divide (progressively during development, PrP staining in neural tube increases as the mantle zone thickened; our unpublished data).

Expression of PrP in extra-embryonic tissue has been described and occurs at early developmental stages [22], [23], [60]. The transcriptomic perturbations observed in the Prnp-knockout embryos affect genes involved in placentation. Adam12, a candidate regulator in trophoblast fusion [61], is under-expressed as well as the Cysteine-Cathepsins which are essential for extra-embryonic development [62]. Activin receptors are also differentially expressed (Table S2). Activin promotes differentiation of mouse trophoblast stem cells [63] and its receptor controls trophoblastic cell proliferation [64]. Differential expression of other key regulators acting on placentation was observed such as that of fibroblast growth factors [65], brain-derived neurotropic factors [66] and proteins involved in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Pou5f1, TDGF1, Mesp1 [54], [67] and potentially Pax8 [68] (Table 3).

Overall, our analysis suggests that, through the deregulation of the above-mentioned transcription factors and key genes involved in the maintenance, renewal and differentiation of stem cells, PrP invalidation affects numerous developmental processes that take place around gastrulation. A biological effect of these deregulations is a perturbation of the cellular interaction and cell homeostasis. In zebrafish, it leads to a morbid phenotype. In mammals, compensatory mechanisms would reduce this phenotype and allow sustaining a nearly normal embryonic development. Recent data suggest that the prion-related Shadoo protein has a crucial role in this process in the absence of PrP [34]. The phenotype associated with the Prnp-knockout, Sprn-knockdown genotype was not clearly identified but our current data support the hypothesis of a lethal defect in early gastrulation in the absence of these prion-related proteins characterized by a default in placentation, angiogenesis and hematopoiesis (Figure 4). Current investigations are underway to assess this hypothesis.

Materials and Methods

Animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the guidelines of the Code for Methods and Welfare Considerations in Behavioural Research with Animals (Directive 86/609EC). And all efforts were made to minimize suffering. Experiments were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the author's institution, INRA (Permit Number RTA06-091). All animal manipulations were done according to the recommendations of the French Commission de Génie Génétique (Permit Number N°12931 (01.16.2003)). Total RNA was isolated from pools of whole FVB/N and FVB/N Prnp−/− mouse embryos at stages E6.5 and E7.5 [9], [69]. RNA extractions were performed using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini kit (Qiagen cat # 75842). RNA concentration was calculated by electro-spectrophotometry and the RNA integrity checked with the Agilent Bioanalyser (Waldbroom, Germany).

RNA samples of 5 microg, obtained from around 30 embryos each collected from 3 to 4 females, were sent to GATC Biotech SARL for RNAseq analysis. A standard cDNA library was derived from each sample, with colligation and nebulization of cDNA and adapter ligation. These cDNAs were analyzed on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II with raw data output of up to 350 Mb and 42,000,000 reads per sample and a read length of 36 bases (single read). Sequence cleaning was done using Seqclean (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/sofware/seqclean_README). Cleaned reads were mapped to the NCBI mouse transcript database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomed/M_musculus/RNA/) using BWA software [70].

Differentially expressed genes between FVB/N and FVB/N Prnp −/− embryos were identified at 5% FDR using the DESeq software from the package R [71]. They were clustered using the software DAVID [72], [73], then classified in pathways by using Ingenuity (http://www.ingenuity.com/) and in networks and biological functions using the GEPS application of Genomatix (http://www.genomatix.de).

RT-PCR analyses were performed using 3 microg of purified RNA reverse transcribed with the SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT-PCR analyses were performed using a set of oligonucleotides located in different exons (Table S1) for each gene analyzed to avoid potential genomic DNA amplification. The PCR conditions comprised 35 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 40 s. Amplified fragments were visualized under UV following size resolution by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of ethidium bromide.

For immunohistochemistry, transverse sections of E9.5 FVB/N formalin-fixed embryos (14 microm-thick) were stained with Sha31 antibody [74]. Images were acquired using a Zeiss microscope. E9.5 FVB/N Prnp −/− embryos were used as negative controls. It should be noted that immunohistochemistry analysis performed on younger embryos led to an artefactual signal, thus preventing the study of expression of PrP at earlier stages.

Supporting Information

A network connecting the differentially expressed genes at E7.5. A network connecting the differentially expressed genes from Prnp Knock-out embryos was identified by GEPS application from Genomatix in which Tlr4 and Igf1 occupy a central role alongside, but to a lesser extent, Cd34 and Thy1. Red color indicates up- and blue down-regulated genes, respectively (see supplementary data Figure 2 for detailed Genomatix network legend).

(TIF)

Genomatix pathway system legend. Description of the genomatix pathway system legend is given. It applies to the figures 2 and 3.

(TIF)

Primer sets used for PCRs.

(DOCX)

List of differentially expressed genes in Prnp -knockout embryos. Up-regulated genes are in green. Down-regulated genes are in red.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

FVB/N Prnp-knockout mice were kindly provided by S. Prusiner (San Francisco, USA).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: R.Y. is a post-doctoral scientist supported by the ANR-09-BLAN-0015-01. S.H. is a post-doctoral scientist supported by an INRA-Transfert fellowship and by the ANR-09-BLAN-0015-01. This work was supported by the ANR-09-BLAN-0015-01 and by the INRA AIP BioRessource PRIFASTEM. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–44. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguzzi A, Heikenwalder M, Polymenidou M. Insights into prion strains and neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:552–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovacs GG, Budka H. Molecular pathology of human prion diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:976–99. doi: 10.3390/ijms10030976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zomosa-Signoret V, Arnaud JD, Fontes P, Alvarez-Martinez MT, Liautard JP. Physiological role of the cellular prion protein. Vet Res. 2008;39:9. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2007048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linden R, Martins VR, Prado MA, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, et al. Physiology of the prion protein. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:673–728. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martins VR, Beraldo FH, Hajj GN, Lopes MH, Lee KS, et al. Prion Protein: Orchestrating Neurotrophic Activities. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2009;12:63–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider B, Pietri M, Pradines E, Loubet D, Launay JM, et al. Understanding the neurospecificity of Prion protein signaling. Front Biosci. 2011;16:169–86. doi: 10.2741/3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strom A, Wang GS, Picketts DJ, Reimer R, Stuke AW, et al. Cellular prion protein localizes to the nucleus of endocrine and neuronal cells and interacts with structural chromatin components. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:414–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bueler H, Fischer M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp HP, et al. Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature. 1992;356:577–82. doi: 10.1038/356577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manson JC, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Aitchison L, McConnell I, et al. 129/Ola mice carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolishes mRNA production are developmentally normal. Mol Neurobiol. 1994;8:121–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02780662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richt JA, Kasinathan P, Hamir AN, Castilla J, Sathiyaseelan T, et al. Production of cattle lacking prion protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:132–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu G, Chen J, Xu Y, Zhu C, Yu H, et al. Generation of goats lacking prion protein. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:3. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallucci GR, Ratte S, Asante EA, Linehan J, Gowland I, et al. Post-natal knockout of prion protein alters hippocampal CA1 properties, but does not result in neurodegeneration. Embo J. 2002;21:202–10. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White MD, Farmer M, Mirabile I, Brandner S, Collinge J, et al. Single treatment with RNAi against prion protein rescues early neuronal dysfunction and prolongs survival in mice with prion disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10238–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802759105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shmerling D, Hegyi I, Fischer M, Blättler T, Brandner S, et al. Expression of amino-terminally truncated PrP in the mouse leading to ataxia and specific cerebellar lesions. Cell. 1998;93:203–14. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prcina M, Kontsekova E. Has prion protein important physiological function? Med Hypotheses. 2011;76:567–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crecelius AC, Helmstetter D, Strangmann J, Mitteregger G, Frohlich T, et al. The brain proteome profile is highly conserved between Prnp−/− and Prnp+/+ mice. Neuroreport. 2008;19:1027–31. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283046157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chadi S, Young R, Le Guillou S, Tilly G, Bitton F, et al. Brain transcriptional stability upon prion protein-encoding gene invalidation in zygotic or adult mouse. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:448. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benvegnu S, Roncaglia P, Agostini F, Casalone C, Corona C, et al. Developmental influence of the cellular prion protein on the gene expression profile in mouse hippocampus. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:711–725. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00205.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manson J, West JD, Thomson V, McBride P, Kaufman MH, et al. The prion protein gene: a role in mouse embryogenesis? Development. 1992;115:117–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miele G, Alejo Blanco AR, Baybutt H, Horvat S, Manson J, et al. Embryonic activation and developmental expression of the murine prion protein gene. Gene Expr. 2003;11:1–12. doi: 10.3727/000000003783992324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tremblay P, Bouzamondo-Bernstein E, Heinrich C, Prusiner SB, DeArmond SJ. Developmental expression of PrP in the post-implantation embryo. Brain Res. 2007;1139:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajj GN, Santos TG, Cook ZS, Martins VR. Developmental expression of prion protein and its ligands stress-inducible protein 1 and vitronectin. J Comp Neurol. 2009;517:371–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.22157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang CC, Steele AD, Lindquist S, Lodish HF. Prion protein is expressed on long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells and is important for their self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2184–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510577103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmqvist L, Pineault N, Wasslavik C, Humphries RK. Candidate genes for expansion and transformation of hematopoietic stem cells by NUP98-HOX fusion genes. PLoS One. 2007;2:e768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cervenakova L, Akimov S, Vasilyeva I, Yakovleva O, McKenzie C, et al. Fukuoka-1 strain of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy agent infects murine bone marrow-derived cells with features of mesenchymal stem cells. Transfusion. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.03041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steele AD, Emsley JG, Ozdinler PH, Lindquist S, Macklis JD. Prion protein (PrPc) positively regulates neural precursor proliferation during developmental and adult mammalian neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3416–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511290103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hidaka K, Shirai M, Lee JK, Wakayama T, Kodama I, et al. The cellular prion protein identifies bipotential cardiomyogenic progenitors. Circ Res. 2010;106:111–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee YJ, Baskakov IV. Treatment with normal prion protein delays differentiation and helps to maintain high proliferation activity in human embryonic stem cells. J Neurochem. 2010;114:362–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peralta OA, Huckle WR, Eyestone WH. Expression and knockdown of cellular prion protein (PrPC) in differentiating mouse embryonic stem cells. Differentiation. 2011;81:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.09.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malaga-Trillo E, Solis GP, Schrock Y, Geiss C, Luncz L, et al. Regulation of embryonic cell adhesion by the prion protein. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e55. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nourizadeh-Lillabadi R, Seilo Torgersen J, Vestrheim O, Konig M, Alestrom P, et al. Early embryonic gene expression profiling of zebrafish prion protein (Prp2) morphants. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malaga-Trillo E, Salta E, Figueras A, Panagiotidis C, Sklaviadis T. Fish models in prion biology: underwater issues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:402–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young R, Passet B, Vilotte M, Cribiu EP, Beringue V, et al. The prion or the related Shadoo protein is required for early mouse embryogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilhelm BT, Landry JR. RNA-Seq-quantitative measurement of expression through massively parallel RNA-sequencing. Methods. 2009;48:249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams H, Johnson JL, Jackson CL, White SJ, George SJ. MMP-7 mediates cleavage of N-cadherin and promotes smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res. 87:137–46. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biswas S, Emond MR, Jontes JD. Protocadherin-19 and N-cadherin interact to control cell movements during anterior neurulation. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1029–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGary EC, Lev DC, Bar-Eli M. Cellular adhesion pathways and metastatic potential of human melanoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:459–65. doi: 10.4161/cbt.1.5.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Satoh J, Kuroda Y, Katamine S. Gene expression profile in prion protein-deficient fibroblasts in culture. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64517-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostlund P, Lindegren H, Pettersson C, Bedecs K. Up-regulation of functionally impaired insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36110–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrette B, Calvo E, Vallieres N, Lacroix S. Transcriptional profiling of the injured sciatic nerve of mice carrying the Wld(S) mutant gene: identification of genes involved in neuroprotection, neuroinflammation, and nerve regeneration. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:1254–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.07.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babaie Y, Herwig R, Greber B, Brink TC, Wruck W, et al. Analysis of Oct4-dependent transcriptional networks regulating self-renewal and pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:500–10. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pelton TA, Sharma S, Schulz TC, Rathjen J, Rathjen PD. Transient pluripotent cell populations during primitive ectoderm formation: correlation of in vivo and in vitro pluripotent cell development. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:329–39. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao F, Maiti S, Sun G, Ordonez NG, Udtha M, et al. The Wt1+/R394W mouse displays glomerulosclerosis and early-onset renal failure characteristic of human Denys-Drash syndrome. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9899–910. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9899-9910.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bedi A, Kovacevic D, Hettrich C, Gulotta LV, Ehteshami JR, et al. The effect of matrix metalloproteinase inhibition on tendon-to-bone healing in a rotator cuff repair model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:384–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, DeWitt DL, McNeely TB, Wahl SM, Wahl LM. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor suppresses the production of monocyte prostaglandin H synthase-2, prostaglandin E2, and matrix metalloproteinases. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:894–900. doi: 10.1172/JCI119254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aguzzi A, Calella AM. Prions: protein aggregation and infectious diseases. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1105–52. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris DA, True HL. New insights into prion structure and toxicity. Neuron. 2006;50:353–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiang W, Windl O, Wunsch G, Dugas M, Kohlmann A, et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes in scrapie-infected mouse brains by using global gene expression technology. J Virol. 2004;78:11051–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11051-11060.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorensen G, Medina S, Parchaliuk D, Phillipson C, Robertson C, et al. Comprehensive transcriptional profiling of prion infection in mouse models reveals networks of responsive genes. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hwang D, Lee IY, Yoo H, Gehlenborg N, Cho JH, et al. A systems approach to prion disease. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:252. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spinner DS, Cho IS, Park SY, Kim JI, Meeker HC, et al. Accelerated prion disease pathogenesis in Toll-like receptor 4 signaling-mutant mice. J Virol. 2008;82:10701–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00522-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saga Y, Kitajima S, Miyagawa-Tomita S. Mesp1 expression is the earliest sign of cardiovascular development. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000;10:345–52. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindsley RC, Gill JG, Murphy TL, Langer EM, Cai M, et al. Mesp1 coordinately regulates cardiovascular fate restriction and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in differentiating ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakajima H, Ito M, Smookler DS, Shibata F, Fukuchi Y, et al. TIMP-3 recruits quiescent hematopoietic stem cells into active cell cycle and expands multipotent progenitor pool. Blood. 2010;116:4474–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim SM, Pereira L, Wong MS, Hirst CE, Van Vranken BE, et al. Enforced expression of Mixl1 during mouse ES cell differentiation suppresses hematopoietic mesoderm and promotes endoderm formation. Stem Cells. 2009;27:363–74. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bianco C, Rangel MC, Castro NP, Nagaoka T, Rollman K, et al. Role of Cripto-1 in stem cell maintenance and malignant progression. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:532–40. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson KD, Pan L, Yang XM, Hughes VC, Walls JR, et al. Angiogenic sprouting into neural tissue requires Gpr124, an orphan G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019761108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Christoffels VM, Mommersteeg MT, Trowe MO, Prall OW, de Gier-de Vries C, et al. Formation of the Venous Pole of the Heart From an Nkx2–5–Negative Precursor Population Requires Tbx18. Circ Res. 2006;98:1555–63. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227571.84189.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hwang HS, Park SH, Park YW, Kwon HS, Sohn IS. Expression of cellular prion protein in the placentas of women with normal and preeclamptic pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1155–61. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.498497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huppertz B, Bartz C, Kokozidou M. Trophoblast fusion: fusogenic proteins, syncytins and ADAMs, and other prerequisites for syncytial fusion. Micron. 2006;37:509–17. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Screen M, Dean W, Cross JC, Hemberger M. Cathepsin proteases have distinct roles in trophoblast function and vascular remodelling. Development. 2008;135:3311–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.025627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Natale DR, Hemberger M, Hughes M, Cross JC. Activin promotes differentiation of cultured mouse trophoblast stem cells towards a labyrinth cell fate. Dev Biol. 2009;335:120–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Munir S, Xu G, Wu Y, Yang B, Lala PK, et al. Nodal and ALK7 inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in human trophoblast cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31277–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhong W, Wang QT, Sun T, Wang F, Liu J, et al. FGF ligand family mRNA expression profile for mouse preimplantation embryos, early gestation human placenta, and mouse trophoblast stem cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73:540–50. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawamura K, Kawamura N, Sato W, Fukuda J, Kumagai J, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes implantation and subsequent placental development by stimulating trophoblast cell growth and survival. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3774–82. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang HJ, Siu MK, Wong ES, Wong KY, Li AS, et al. Oct4 is epigenetically regulated by methylation in normal placenta and gestational trophoblastic disease. Placenta. 2008;29:549–54. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kozmik Z, Kurzbauer R, Dorfler P, Busslinger M. Alternative splicing of Pax-8 gene transcripts is developmentally regulated and generates isoforms with different transactivation properties. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6024–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giri RK, Young R, Pitstick R, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, et al. Prion infection of mouse neurospheres. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3875–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510902103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–95. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feraudet C, Morel N, Simon S, Volland H, Frobert Y, et al. Screening of 145 anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies for their capacity to inhibit PrPSc replication in infected cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11247–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A network connecting the differentially expressed genes at E7.5. A network connecting the differentially expressed genes from Prnp Knock-out embryos was identified by GEPS application from Genomatix in which Tlr4 and Igf1 occupy a central role alongside, but to a lesser extent, Cd34 and Thy1. Red color indicates up- and blue down-regulated genes, respectively (see supplementary data Figure 2 for detailed Genomatix network legend).

(TIF)

Genomatix pathway system legend. Description of the genomatix pathway system legend is given. It applies to the figures 2 and 3.

(TIF)

Primer sets used for PCRs.

(DOCX)

List of differentially expressed genes in Prnp -knockout embryos. Up-regulated genes are in green. Down-regulated genes are in red.

(DOCX)