Abstract

The genomes of numerous parasitic nematodes are currently being sequenced, but their complexity and size, together with high levels of intra-specific sequence variation and a lack of reference genomes, makes their assembly and annotation a challenging task. Haemonchus contortus is an economically significant parasite of livestock that is widely used for basic research as well as for vaccine development and drug discovery. It is one of many medically and economically important parasites within the strongylid nematode group. This group of parasites has the closest phylogenetic relationship with the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans, making comparative analysis a potentially powerful tool for genome annotation and functional studies. To investigate this hypothesis, we sequenced two contiguous fragments from the H. contortus genome and undertook detailed annotation and comparative analysis with C. elegans. The adult H. contortus transcriptome was sequenced using an Illumina platform and RNA-seq was used to annotate a 409 kb overlapping BAC tiling path relating to the X chromosome and a 181 kb BAC insert relating to chromosome I. In total, 40 genes and 12 putative transposable elements were identified. 97.5% of the annotated genes had detectable homologues in C. elegans of which 60% had putative orthologues, significantly higher than previous analyses based on EST analysis. Gene density appears to be less in H. contortus than in C. elegans, with annotated H. contortus genes being an average of two-to-three times larger than their putative C. elegans orthologues due to a greater intron number and size. Synteny appears high but gene order is generally poorly conserved, although areas of conserved microsynteny are apparent. C. elegans operons appear to be partially conserved in H. contortus. Our findings suggest that a combination of RNA-seq and comparative analysis with C. elegans is a powerful approach for the annotation and analysis of strongylid nematode genomes.

Introduction

H. contortus is a parasitic nematode of small ruminants of major economic importance. It is also one of the most experimentally tractable parasitic nematodes and is widely used as a model parasite for studies on basic parasite biology [1], [2], vaccine development [3], [4], drug discovery [5] and anthelmintic resistance [6]–[8]. Comparative genomic analysis between H. contortus and C. elegans is essential to explore the extent and limitations in which C. elegans can be used as a model for the strongylids and will have reciprocal benefits for research on this widely-studied nematode.

There has been a recent explosion in the number of nematode genomes being sequenced. However, experience from other organisms shows that draft genome assemblies vary enormously in quality and this creates huge problems for research communities and significantly reduces the value of the resources [9]. Hence, the major challenge facing parasitic nematode genomics is not genome sequencing per se, but assembly and annotation. The production of a high quality finished genome sequence for H. contortus is an important aim as it will provide a reference genome for many parasitic nematodes in the strongylid nematode group. These include some of the most important “neglected tropical diseases” of humans and economically important parasites of livestock, many of which are currently being sequenced to varying levels of completion (e.g. http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/downloads/helminths/ and http://www.nematode.net/). However, the assembly of the H. contortus genome is a major challenge, predominantly due to genome size and sequence polymorphism; factors likely to be common to many other nematode genomes. The latest assembly of ∼4 Gb capillary, 454 and Illumina sequencing has generated a 393 Mb assembly, with a contig N50 of 6447 bp and mean length of 3520 bp. The contig sizes are not sufficiently large to allow a detailed global analysis of genome organisation and gene structure or to undertake a comprehensive comparative analysis with C. elegans. Consequently, to investigate the utility of RNA-seq together with comparative analysis with C. elegans for strongylid nematode genome annotation, we have undertaken detailed annotation of two large and manually finished contiguous regions (409 kb and 181 kb). We have used Illumina technology to sequence the adult H. contortus transcriptome and used the RNA-seq data to annotate the genomic sequences at a single nucleotide level. Here we present the results of this annotation, along with a comparative analysis of H. contortus and C. elegans gene structure and genome organisation.

Results

Illumina technology was used to sequence the adult H. contortus MHco3 (ISE) isolate transcriptome. 38 million 76 bp reads were generated and mapped onto genomic sequence to guide annotation of a 409 kb overlapping BAC tiling path (X-linked contig) and a 181 kb BAC insert sequence (BAC BH4E20). In total, the 590 kb genomic sequence had a GC content of 43%, with a 47.6% and 46.3% GC content for the identified coding sequence in the X-linked contig and BAC BH4E20 respectively. These figures were slightly higher than the C. elegans genome GC content of 35.4% and exon GC content of 42.7% [10].

Gene density is lower on the H. contortus contigs than on equivalent regions of the C. elegans genome

A total of 52 transcripts were identified across the two contigs. 37 were coding sequences mapped with RNA-seq: 16 transcripts on the X-linked contig and 21 transcripts on BAC BH4E20. An additional 14 coding sequences with a low coverage of mapped reads were predicted on the X-linked contig with the gene prediction software Genefinder. One β-tubulin gene, hc-18h7-1, was annotated from sequenced cDNA. 12 of the 52 transcripts were identified as transposable elements (TEs), so were excluded from the analysis of gene density and structure and are discussed later.

Thus, 40 putative genes were identified in a total of 590 kb genomic sequence, which is a density of one gene per 14.75 kb. The genome average for C. elegans is one gene per 5 kb [10]. 23 of these transcripts were identified on the 409 kb X-linked contig, which is a density of one gene per 17.78 kb. The average gene density on the X chromosome in C. elegans is one gene per 6.54 kb [10]. 17 transcripts were identified on the 181 kb BAC insert BH4E20, which is a density of one gene per 10.65 kb, relative to a C. elegans average of one gene per 4.77–5.06 kb on chromosome I, the range reflecting a higher density in the central cluster region than in the arms [10].

Comparison of orthologous genes suggests gene size is significantly larger in H. contortus than C. elegans

The conceptual translations of 22 transcripts were most similar to C. elegans proteins, eleven transcripts were most similar to C. briggsae predicted proteins and three were most similar to Brugia malayi proteins, based on current NCBI databases. The conceptual translations of three transcripts were most similar to proteins outside Nematoda. One transcript, hc-bh4e20-1, predicted to encode a P-glycoprotein (PGP) shared most identity with a published H. contortus PGP polypeptide (accession number AAC38987), but was also highly similar to C. elegans PGP-2.

Homologous proteins (BLASTp, Expect-value (E)>1e-10) were identifiable in C. elegans for all three predicted polypeptides with most identity to B. malayi proteins. For the three genes with a closest match outside Nematoda, two encoded proteins that were highly conserved in many species (hc-13c1-3 encoded a putative RNA-binding protein and hc-bh4e20-15 encoded a putative high mobility group protein) and both had homology (BLASTp, E>1e-10) to proteins in C. elegans. The third gene, hc-13c1-2, encoded a conserved F-box domain yet shared little identity with any sequence in NCBI databases.

To assess the extent of conservation of gene structure between H. contortus and C. elegans, a subset of 24 putative orthologues of C. elegans genes were identified in the annotated parasite sequence. The inherent risk in inferring an orthologous or paralogous relationship between C. elegans genes and those from the incomplete H. contortus genome is that closer relatives may be identified when the parasite genome is fully sequenced. With this caveat in mind, 21 H. contortus putative orthologues of C. elegans genes were identified using sequence similarity criteria (see Materials and Methods), while a further three were identified through conserved microsynteny. Gene hc-18h7-3 lies within the fourth intron of gene hc-18h7-2 on the complementary strand, an identical relationship to their closest matched genes, zk154.1 and zk154.4, in C. elegans (Figure 1). Gene hc-bh4e20-6 lies on the same strand and directly upstream of the orthologue of C. elegans ath-1, and shares most homology with k04g2.11, the corresponding upstream gene in C. elegans (Figure 2). This conservative subset of 24 orthologous genes was used to directly compare H. contortus and C. elegans gene structure (Table 1).

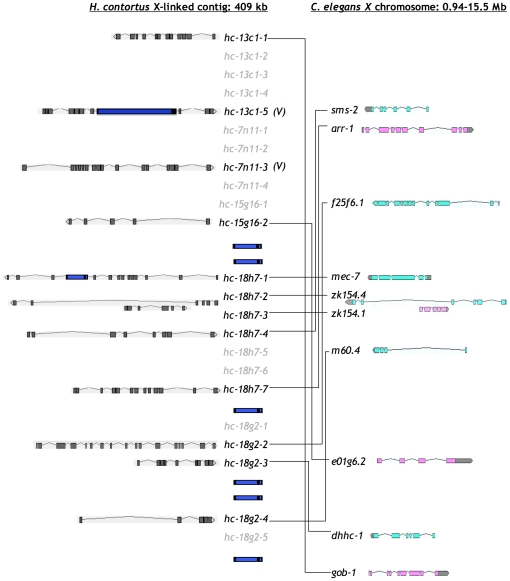

Figure 1. Conserved microsynteny between H. contortus X-linked contig and C. elegans X chromosome.

Putative orthologues are in black type, genes with no clear orthologues are in grey type and transposon insertions are shown as dark blue ORFs. Colinearity is maintained in H. contortus orthologues of C. elegans mec-7, zk154.4 and zk154.1. hc-13c1-5 and hc-7n11-3 are orthologous with genes on C. elegans chromosome V.

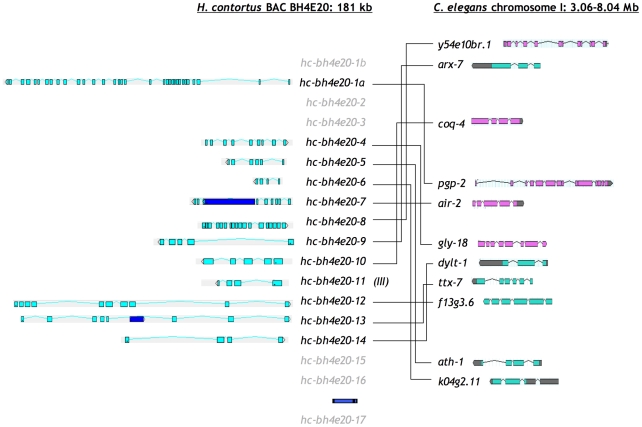

Figure 2. Conserved microsynteny between H. contortus BAC BH4E20 and C. elegans chromosome I.

Putative orthologues are in black type, genes with no clear orthologues are in grey type and transposon insertions are shown as dark blue ORFs. Colinearity is maintained in H. contortus orthologues of C. elegans y54e10br.1 and arx-7, orthologues of C. elegans dylt-1, ttx-7 and f13g3.6 and orthologues of C. elegans ath-1 and k04g2.11. The last two gene sets are in operons in C. elegans. hc-bh4e20-11 is orthologous with f53a3.7 on C. elegans chromosome III.

Table 1. Subset of 24 C. elegans and H. contortus putative orthologues.

| H. contortus | C. elegans | ||||||||

| Gene | Unspliced | Spliced | Introns | Gene | Unspliced | Spliced | Introns | Chromosome | BLASTp |

| hc-13c1-1 | 4695 | 1437 | 11 | gob-1 | 3408 | 1407 | 8 | X | 8.00E-136 |

| hc-13c1-5 | 4392 | 1200 | 10 | folt-1 | 1566 | 1233 | 4 | V | 5.00E-105 |

| hc-7n11-3 | 8243 | 1596 | 15 | klc-2 | 2402 | 1623 | 4 | V | 0 |

| hc-15g16-2 | 6796 | 636 | 4 | e01g6.2 | 1898 | 615 | 3 | X | 3.00E-41 |

| hc-18h7-1 | 10663 | 1326 | 12 | mec-7 | 1596 | 1326 | 4 | X | 0 |

| hc-18h7-2 | 7731 | 642 | 5 | zk154.4 | 5132 | 612 | 5 | X | 5.00E-17 |

| hc-18h7-3 | 3341 | 912 | 5 | zk154.1 | 895 | 630 | 4 | X | 1.00E-78 |

| hc-18h7-4 | 8954 | 1059 | 7 | sms-2 | 3616 | 1008 | 5 | X | 6.00E-149 |

| hc-18h7-7 | 6811 | 1443 | 11 | arr-1 | 3230 | 1308 | 9 | X | 8.00E-180 |

| hc-18g2-2 | 9409 | 2667 | 16 | f25f6.1 | 5991 | 2340 | 12 | X | 1.00E-135 |

| hc-18g2-3 | 3556 | 879 | 8 | dhhc-1 | 2218 | 888 | 5 | X | 1.00E-92 |

| hc-18g2-4 | 5360 | 486 | 4 | m60.4 | 3871 | 489 | 3 | X | 1.00E-59 |

| hc-bh4e20-1a | 18110 | 3825 | 32 | pgp-2 | 9012 | 3819 | 13 | I | 0 |

| hc-bh4e20-4 | 4766 | 1035 | 8 | gly-18 | 2048 | 1323 | 7 | I | 7.00E-78 |

| hc-bh4e20-5 | 3295 | 660 | 5 | ath-1 | 1656 | 672 | 3 | I | 7.00E-83 |

| hc-bh4e20-6 | 1371 | 357 | 3 | k04g2.11 | 352 | 258 | 2 | I | 3.00E-08 |

| hc-bh4e20-7 | 2799 | 846 | 8 | air-2 | 1206 | 918 | 4 | I | 4.00E-87 |

| hc-bh4e20-8 | 4921 | 2646 | 17 | y54e10br.1 | 9937 | 2739 | 12 | I | 0 |

| hc-bh4e20-9 | 2633 | 459 | 4 | arx-7 | 645 | 459 | 2 | I | 8.00E-56 |

| hc-bh4e20-10 | 1558 | 708 | 4 | coq-4 | 844 | 696 | 3 | I | 1.00E-87 |

| hc-bh4e20-11 | 1258 | 396 | 3 | f53a3.7 | 485 | 360 | 2 | III | 7.00E-26 |

| hc-bh4e20-12 | 6998 | 1173 | 9 | f13g3.6 | 1343 | 1074 | 5 | I | 4.00E-92 |

| hc-bh4e20-13 | 6517 | 858 | 7 | ttx-7 | 1805 | 858 | 5 | I | 3.00E-118 |

| hc-bh4e20-14 | 3107 | 348 | 3 | dylt-1 | 543 | 321 | 2 | I | 1.00E-31 |

| Average | 5720.17 | 1149.75 | 8.79 | 2737.46 | 1124.00 | 5.25 | |||

| Median | 4843.50 | 895.50 | 7.5 | 1851.5 | 903 | 4 | |||

Sizes in nucleotides or amino acids as appropriate. Unspliced length is genomic sequence from ATG to terminal stop codon (does not include 5′ or 3′ UTR). Spliced length is predicted protein coding sequence only.

The parasite genes had a similar spliced transcript size to their homologues in C. elegans, but unspliced transcript size was invariably larger, which was a function of both a greater number of introns and a larger intron size in H. contortus (Table 1). Average unspliced transcript length was 5.72 kb (median 4.84 kb) compared to an average of 2.74 kb (median 1.85 kb) for the orthologous gene set in C. elegans and an average of 2.5 kb (median 1.91 kb) in the C. elegans genome [11], [12]. Predicted UTRs were excluded in the above calculations and any transcribed sequences located within an intron (e.g. putative transposable elements and genes hc-18h7-3 and zk154.1) were subtracted from the unspliced transcript size.

The average number of introns was 8.79 per gene (median 7.5) in H. contortus compared to an average of 5.25 introns per gene (median 4) in the orthologous gene set in C. elegans and a genome average of 4 per gene (median 5) in the model worm [12], [13]. The average intron size in this H. contortus subset was 520 bp compared to an average intron size of 360 bp in the C. elegans orthologues. The genome average intron size for C. elegans is 466.6 bp, although this is skewed by a small number of very large introns, giving a more representative median of 65 bp [13], [14]. The average for C. elegans in this subset was inflated by a large first intron in gene m60.4, which is conserved in the orthologous gene, hc-18g2-4, in H. contortus (Figure 1).

Synteny/Colinearity between H. contortus and C. elegans

A previous study showed that the 409 kb contig was X-linked in H. contortus based on male/female genotyping and inheritance of a panel of six microsatellites distributed along the contig [15]. Of the 12 H. contortus genes on this contig with clear putative orthologues in C. elegans, ten had orthologues located on the C. elegans X chromosome and the remaining two had orthologues on C. elegans chromosome V (Figure 1). Although these ten genes were located within a small (409 kb) region of the H. contortus X chromosome, the orthologues were spread over more than 14 Mb of the C. elegans X chromosome, with generally poor conservation of long range gene order and polarity (Figure 1). However, a single region of conserved microsynteny was apparent between genes hc-18h7-1, hc-18h7-2 and hc-18h7-3 in H. contortus and mec-7, zk154.1 and zk154.4 on the X chromosome in C. elegans.

For BAC BH4E20, of the 12 predicted polypeptides that had clear orthologues in C. elegans, 11 of these were encoded on C. elegans chromosome I and one, HC-BH4E20-11, was encoded on C. elegans chromosome III (Figure 2). Again, these orthologues were scattered across a large region of C. elegans chromosome I despite being located on this relatively small region (181 kb) of the H. contortus genome with little long range synteny or conservation of polarity. However, three regions of microsynteny were apparent: H. contortus genes hc-bh4e20-8 and hc-bh4e20-9 had a conserved relationship relative to the orthologous C. elegans genes y54e10br.1 and arx-7; as did H. contortus genes hc-bh4e20-12, hc-bh4e20-13 and hc-bh4e20-14 to C. elegans genes dylt-1, ttx-7 and f13g3.6; and H. contortus genes hc-bh4e20-5 and hc-bh4e20-6 to C. elegans genes ath-1 and k04g2.11.

In order to investigate whether the syntenic relationships of the two large H. contortus contigs with C. elegans sequence was likely to be representative across the genome, a survey analysis of BAC end derived sequence was undertaken. The H. contortus BAC end database contains 20,828 sequences of an average of 760 bp, corresponding to each end of 10,414 BAC inserts. This dataset was used for a BLASTx search of C. elegans Wormpep and the locus of the best-matched C. elegans gene for every hit with P<0.01 was recorded. 233 BAC inserts had matches to C. elegans proteins at both ends using these criteria (Supplementary Information, Table 1). 118 of these BAC end pairs (50.64%) hit C. elegans genes on the same chromosome compared to 16.67% that would be expected by chance if there was no conservation of chromosomal location. Although the BLASTx matches cannot be claimed to represent definite orthologous pairs, a random selection of genes would not be expected to yield a higher linkage estimate. This suggests there is a high degree of chromosomal synteny between H. contortus and C. elegans genomes, consistent with our analysis of the two large contigs.

Trans-splicing of the annotated H. contortus genes

Around 15% of C. elegans genes are in operons. Although both SL1 and SL2 trans-splicing has been described in H. contortus, its frequency of occurrence and relationship to operon structure is unknown [16]–[18]. In order to investigate which genes on the two annotated contigs were trans-spliced to SL1 and SL2, transcriptome reads containing SL1 and SL2 sequences were identified and trimmed to remove the spliced leader sequence, then mapped against the annotated sequence of the X-linked contig and BAC BH4E20 (SL RNA-seq). The results are shown in Table 2. No SL RNA-seq reads were detected for 26 genes. Of the remainder, ten genes were trans-spliced with SL1, two genes were trans-spliced with SL2 sequences and two genes were trans-spliced with SL1 and SL2 sequences. Alternative start codons were identified for six genes and the same spliced leader was used for alternative transcripts of the same gene (Table 2).

Table 2. Trans-splicing.

| Gene | Spliced Leader | Alternative Start Codon | Intergenic Distance if SL2 Trans-spliced |

| hc-13c1-1 | SL1 | first codon exon 2 (SL1) | |

| hc-13c1-4 | |||

| hc-13c1-5 | |||

| hc-18g2-2 | |||

| hc-18g2-3 | SL1 | mid exon 2 (SL1) | |

| hc-18g2-4 | SL1 | ||

| hc-18h7-1 | |||

| hc-18h7-2 | |||

| hc-18h7-3 | |||

| hc-18h7-4 | |||

| hc-18h7-7 | SL1 | mid exon 2 (SL1) | |

| hc-7n11-3 | |||

| hc-18h7-6 | |||

| hc-13c1-2 | |||

| hc-13c1-3 | SL1 | ||

| hc-15g16-1 | SL1 | ||

| hc-15g16-2 | SL2 | no upstream gene for >35 kb | |

| hc-18h7-5 | |||

| hc-7n11-1 | |||

| hc-7n11-2 | SL1 | ||

| hc-7n11-4 | |||

| hc-18g2-1 | |||

| hc-18g2-5 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-1a | |||

| hc-bh4e20-2 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-3 | SL2 | all upstream genes on opposite strand for >47 kb | |

| hc-bh4e20-4 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-5 | SL1/SL2 | first codon exon 2 (SL1/SL2) | 1538 bp downstream from hc-bh4e20-6 on same strand |

| hc-bh4e20-6 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-7 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-8 | SL1 | ||

| hc-bh4e20-9 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-10 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-11 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-12 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-13 | |||

| hc-bh4e20-14 | SL1/SL2 | 403 bp downstream from hc-bh4e20-13 on same strand | |

| hc-bh4e20-15 | SL1 | mid exon 2 (SL1) | |

| hc-bh4e20-16 | SL1 | ||

| hc-bh4e20-17 |

The spliced leader trans-spliced to each transcript was identified using SL-trimmed RNA-seq data where available. Alternative start codons were identified for six transcripts and the same spliced leader was used for alternative transcripts of the same gene. Intergenic distance of the nearest upstream gene is shown for the four sequences trans-spliced to SL2.

Operon structure is partially conserved between H. contortus and C. elegans

Of the 12 H. contortus genes on the X-linked contig that had orthologues in C. elegans, only one, hc-13c1-1, had a C. elegans orthologue that was in an operon. This was gob-1, which is in operon CEOPX136 and is transcribed with the downstream gene h13n06.4. However, the H. contortus gob-1 orthologue, hc-13c1-1, has no identifiable gene within the 10 kb available downstream sequence based on BLASTx similarity, RNA-seq or Genefinder predictions suggesting this gene is not in an operon in H. contortus. A reciprocal BLAST search with the H13N06.4 polypeptide hit no sequence within the BAC contig database as expected, but did identify homologous sequence in the supercontig database (N terminus on supercontig_0011013: tBLASTn E = 8.1e-27, C terminus on supercontig_0033730: tBLASTn E = 2.3e-30) suggesting the orthologous gene exists elsewhere in the H. contortus genome. This gene appears to be expressed as RNA-seq reads map to its coding sequence on both supercontigs. hc-13c1-1 is SL1 trans-spliced.

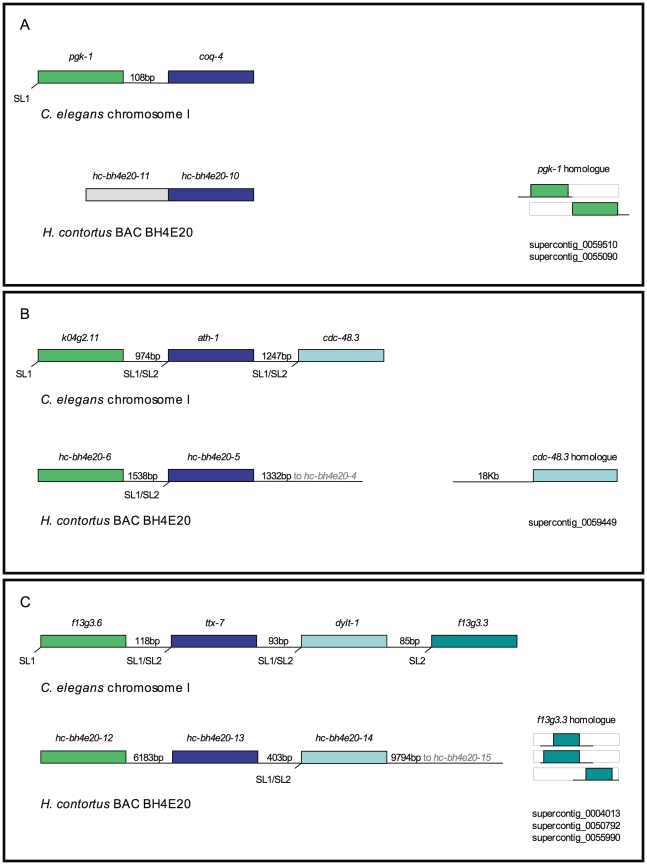

Of the 12 H. contortus genes on BAC BH4E20 that have C. elegans orthologues on chromosome I, six of the C. elegans genes are known to be in operons: coq-4 in CEOP1124, k04g2.11 and ath-1 in CEOP1449 and f13g3.6, ttx-7, dylt-1 in CEOP1388. As shown in Figure 3, there seems to be partial conservation of these operons. Genes that are ‘missing’ from putative H. contortus orthologues of C. elegans operons can be identified elsewhere in the genome. Some of these genes appear to be expressed, including H. contortus orthologues of downstream genes in C. elegans operons, which lack their own promoter sequences in C. elegans.

Figure 3. H. contortus orthologues of genes in operons in C. elegans.

A. C. elegans coq-4 is transcribed in an operon with upstream gene pgk-1. An H. contortus orthologue for coq-4 but not for pgk-1 was identified on BAC BH4E20. However, homologous sequence to pgk-1 was identified in the supercontig database (supercontig_0059510: tBLASTn E = 4e-30, supercontig_0055090: tBLASTn E = 4. 5e-35), suggesting the orthologue exists elsewhere in the genome. The putative H. contortus orthologues of both coq-4 (hc-bh4e20-10) and pgk-1 are expressed, as shown by a large number of RNA-seq reads mapping to their loci. B. ath-1 is transcribed in the middle of a three-gene operon in C. elegans with k04g2.11 upstream and cdc-48.3 downstream. ath-1 and k04g2.11 orthologues, hc-bh4e20-5 and hc-bh4e20-6, were identified on H. contortus BAC BH4E20. The intergenic region between the parasite genes was 1538 bp. An orthologue of the downstream gene cdc-48.3 was not identified on the sequence studied, but was on supercontig_0059449 (tBLASTn E = 7.5e-84). RNA-seq data suggested it was highly expressed and no upstream gene was identified in the available 18 kb. No SL-trimmed reads mapped to hc-bh4e20-6, but both SL1 and SL2 reads mapped to hc-bh4e20-5, consistent with it being a downstream gene in an operon. C. C. elegans f13g3.6, ttx-7 and dylt-1 are transcribed in a four-gene operon with downstream gene f13g3.3. The orthologues of f13g3.6, ttx-1 and dylt-1 were collinear on BAC BH4E20, but an orthologue of f13g3.3 was not identified. However, sequence with homology to the F13G3.3 polypeptide was present in the H. contortus supercontig database (supercontig_0004013 tBLASTn E = 6.7e-23, supercontig_0050792 tBLASTn E = 4.3e-17, supercontig_0055990 tBLASTn E = 6.2e-12), although no upstream sequence was available for analysis. No RNA-seq reads mapped to the sequence with homology to f13g3.3 on the three supercontigs, so this gene may not be expressed in H. contortus. Both SL1 and SL2 reads mapped to hc-bh4e20-14, consistent with it being a downstream gene in an operon.

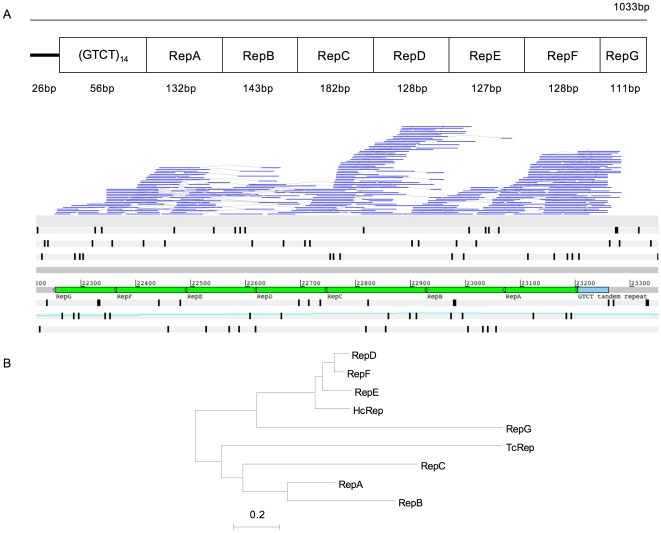

An HcRep sequence cluster is associated with a duplication breakpoint

Characteristic repeat elements ‘HcRep’ and ‘TcRep’ have previously been described in the H. contortus and T. circumcincta genomes respectively [19], [20]. Seven copies of an HcRep-like sequence are present on BAC BH4E20, as an array in intron 15 of hc-bh4e20-1a (Figures 4 and 5). The first three copies (A–C) of the repeat element are most divergent, sharing more similarity to TcRep in T. circumcincta (accession number M84610) while copies D–G are more similar to the published HcRep consensus sequence (accession number U86701). The repeat elements are associated with an upstream (GTCT)14 tandem repeat. RNA-seq reads mapped to all seven copies of the repeat element, indicating HcRep-like sequences are expressed elements in the H. contortus genome. However, the expression level of these particular copies on BAC BH4E20 is not known since the RNA-seq reads may be mapping from expressed HcRep-like elements elsewhere in the genome. Previous studies have estimated over 0.1% of the H. contortus genome is related to HcRep1 based on Southern blot hybridisation intensity using the SE isolate [21]. A BLASTn search of the H. contortus supercontig database identified over 3000 matches (P<1e-05) to the published HcRep consensus sequence.

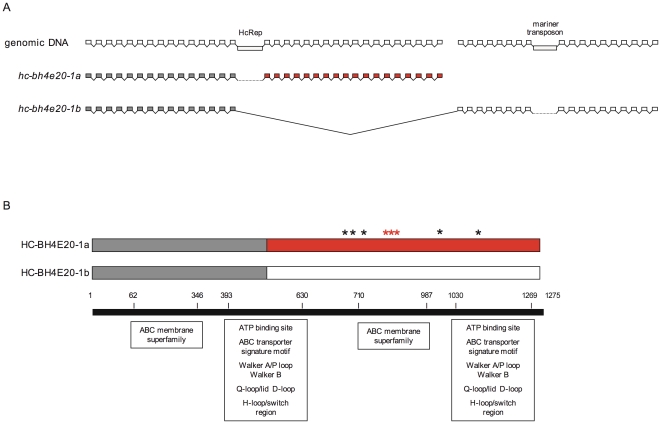

Figure 4. Possible alternative splicing of a P-glycoprotein.

A. The last 36 exons of gene hc-bh4e20-1, a putative P-glycoprotein, appear to consist of a duplicated 18 exon region. The breakpoint is associated with an HcRep cluster. Intron and exon sizes are not to relative scale. B. The alternative 3′ ends of gene hc-bh4e20-1 share 95% nucleotide identity, and the C-termini of the predicted polypeptides share 99% amino acid identity. Two of the five amino acid substitutions (black asterisks) lie within conserved domains and there is a three amino acid indel (red asterisks) within the ABC membrane superfamily domain of the C-terminus. Amino acid co-ordinates of the conserved domains are shown.

Figure 5. Seven copies of HcRep sequence identified on BAC BH4E20.

A. Seven copies of the repeat element HcRep were identified on BAC BH4E20 and RNA-seq suggests they are expressed in the H. contortus genome. An Artemis screenshot shows the adjoining HcRep repeats (green), varying in length from 111 bp to 182 bp, and their association with a 56 bp GTCT tandem repeat (light blue). B. A neighbour-joining tree based on multiple sequence nucleotide alignment shows RepD, RepE, RepF and RepG share most homology with the published H. contortus HcRep consensus sequence (accession no. U86701), while RepA, RepB and RepC are more similar to T. circumcincta repeat element TcRep (accession no. M84610).

The gene within which the HcRep cluster is located, hc-bh4e20-1a, encodes a full-length P-glycoprotein, with the highest homology to C. elegans PGP-2 (Figure 4A and 4B). This gene has an interesting structure that suggests the HcRep cluster may be associated with a duplication break point. The last 36 exons of the gene, immediately downstream of the HcRep cluster, appear to consist of a duplicated 18 exon region. There is 99% amino acid identity between the putative translation products of the duplicated region, which appear to represent alternative splice variants of hc-bh4e20-1a to produce two different transcripts. There is also sequence with homology to a mariner transposase within the 23rd intron of the putative hc-bh4e20-1b spliced isoform.

Mobile elements

Twelve putative transposable elements (TEs), eight of which contained transposon-associated conserved domains were identified on the two large contigs. Four putative polypeptides, sharing homology with the retrotransposon rte-1 in C. elegans, had exonuclease endonuclease phosphatase, reverse transcriptase-like superfamily and non-long-terminal repeat retrotransposon and non-long terminal repeat retrovirus reverse transcriptase domains. Three putative polypeptides had conserved transposase-1 domains and one polypeptide had conserved pao retrotransposon peptidase and reverse transcriptase-like superfamily domains. Four transcripts shared most identity with TEs in other species but did not encode conserved domains (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Table S2).

RNA-seq reads mapped to nine of the 12 TEs. One of the remaining three, TE2, has no start methionine, so may represent a pseudogene. Although these results indicate that members of these TE families are transcriptionally active in the H. contortus genome, the extent to which these specific TE loci are transcribed is unclear. Inherent in the process of aligning whole transcriptome reads to only a portion of the genome, is the possibility that reads from a transcribed TE elsewhere in the genome could be mapped to a non-transcribed loci; in other words, reads from a functional TE could map to non-functional daughter progeny or to remnant sequence at ancient loci.

Discussion

Gene structure and content

H. contortus is a member of the closest phylogenetic clade of parasitic nematodes to C. elegans and the last common ancestor is estimated to have existed 400 million years ago [22]. Hence the extent to which genome structure and organisation is conserved between these two organisms is an important question. We have used a next generation transcriptomic approach to annotate two large contigs and these represent the largest contiguous sections of genomic sequence yet annotated for a strongylid nematode. One contig is known to be located on the X chromosome from previous genetic studies and this is supported by syntenic relationships of the annotated genes. The second contig is likely to be autosomal, being syntenic with C. elegans chromosome I.

The results of our annotations suggest gene size is consistently larger in H. contortus than in C. elegans with the average and median gene sizes being more than two-fold greater in the parasite than for orthologous genes in C. elegans. This is due to both a larger intron number and a larger intron length, with the mean spliced transcript size being very similar between the two species. This larger gene size is reflected in the gene density on the contigs, which is two to three times lower than occurs in C. elegans. The gene density on the X-linked contig is significantly less than on BAC BH4E20 consistent with a lower gene density on the X-chromosome than on the autosomes as is the case in C. elegans [10].

All annotated protein-coding genes, other than hc-13c1-2, had putative homologues in C. elegans. This represents 97.5% gene conservation, a significantly higher percentage than the ∼65% previously estimated with EST analysis [23]. The lowest BLASTp E value of 3e-08 recorded in this study corresponded to a BLASTx E value of 2e-09, compared to a BLASTx E value of 10e-5 to 10e-6 (bit score ≥50) in the EST analysis. So the higher figure for gene conservation in this study is unlikely to be explained by a lower stringency level for the identification of homologues, although BLAST E values will vary with the size and composition of the particular databases searched. It is also unlikely that the genes analysed in this work represent a more highly conserved subset than the EST data, but it is possible that homology is more likely to be detected for a survey of full-length genes than for clustered ESTs, as a number of the latter will represent only partial transcripts.

Microsynteny and partial conservation of operons

Twelve genes on the H. contortus X-linked contig had convincing C. elegans orthologues, ten of which were located on the C. elegans X chromosome. Similarly, twelve genes on BAC BH4E20 had convincing C. elegans orthologues, eleven of which were located on C. elegans chromosome I. However, gene order was generally poorly conserved other than for a few gene clusters.

Although this pilot annotation covered only 590 kb of sequence, analysis of BAC end sequences suggest the pattern of a high level of conserved synteny but a low level of conserved gene order between the two species may be reflected throughout the rest of the genome. We identified 233 BACs for which both end sequences matched C. elegans genes and 50% of these pairs had matches on the same C. elegans chromosomes. These matches are not necessarily to orthologues since the full sequence of these genes are not available, so we have not undertaken extensive annotation and analysis. Nevertheless, this is significantly higher than the value expected by chance, suggesting a high level of syntenic conservation between the two species, consistent with the results for the two large contigs. These results are also consistent with studies comparing the C. elegans genome with those of C. briggsae and B. malayi, which detected high rates of rearrangement, with intra-chromosomal rearrangements more common than inter-chromosomal rearrangements [12], [24]–[27]. The rearrangement rate of C. briggsae has been estimated at 0.4–1 chromosomal breakages per Mb per million years [24], which is at least four times that of D. melanogaster [28]. Intra-chromosomal rearrangements are suggested to occur more commonly than inter-chromosomal rearrangements because they require fewer DNA breaks and because the conformation of the nuclear scaffold may maintain the association of local regions [26].

Although the overall gene order was relatively poorly conserved for the two large contigs, regions of conserved microsynteny between H. contortus and C. elegans were apparent. Four regions with collinear genes were identified, one on the X-linked contig and three on BAC BH4E20, two of which contained orthologues of genes in operons in C. elegans. These operons were only partially conserved since none of the H. contortus regions sharing synteny with C. elegans operons encoded the full complement of genes. Putative orthologues for all ‘missing’ genes could be identified elsewhere in the genome and RNA-seq reads mapped to all but one of these genes, suggesting they are expressed. It is unknown if these differences in operon structure represent gene gain to an operon in C. elegans or gene loss from an operon in H. contortus relative to the last common ancestor. The former perhaps seems more likely since once formed, operons are thought to be difficult to break, as downstream genes would be left without promoters [29]. However, breaking of operons is still possible; the 4% of operons that are not conserved between C. elegans and C. briggsae are a result of not only operon gains in C. elegans but also losses in C. briggsae [30]. For example, the same study identified a four-gene operon in C. elegans in which the first three genes were translocated to a different chromosome in C. briggsae. Despite this, all four genes were expressed in C. briggsae and the authors suggested the separated downstream gene had formed an operon with its new upstream gene. A similar mechanism may have facilitated expression of hc-bh4e20-10 in H. contortus. This is a putative orthologue of C. elegans coq-4, a gene expressed downstream of pgk-1 in two-gene operon CEOP1124. Despite hc-bh4e20-10 lacking an upstream orthologue of pgk-1, it appears to be co-expressed with a different upstream gene, hc-bh4e20-11, which shares most homology with f53a3.7 in C. elegans. f53a3.7 is not in an operon in C. elegans, but it is possible that these genes have formed a new operon in H. contortus.

Functional constraints are thought to conserve intergenic regions within operons to approximately 100 bp in C. elegans, although increased intergenic distances have been reported in a small number of downstream genes trans-spliced with SL1 [12], [29], [31]. Operons with intergenic distances of greater than 100 bp (336 bp and 482 bp) have been identified in B. malayi [32], although this again may be facilitated by SL1 trans-splicing of downstream genes, since B. malayi lacks any SL2-like sequences [29]. In this study, intergenic distances of up to 6183 bp have been identified within the putative H. contortus operons and intergenic distances of up to 1538 bp have been identified preceding genes we have shown to be SL2 trans-spliced. Consistent with this, an operon encoding two genes, Hco-des-2H and Hco-deg-3H, with the latter SL2 trans-spliced, has been reported and the intergenic distance is ten times that between the orthologous pair of genes in C. elegans [16].

Mobile elements and repetitive DNA

Approximately 12% of the C. elegans genome is comprised of TEs, although most of these are thought to be no longer mobile [10]. The 12 H. contortus TEs identified in this study represent just over 3% of the 590 kb genomic sequence analysed but the significant number of transcriptome reads mapping to TE loci suggests such elements may be highly active within the H. contortus genome.

Along with mutations generated by DNA-polymerase errors, TE insertions are the main internal drivers of genetic change, and the association of mobile elements with chromosome rearrangements in Caenorhabditis and Drosophila are well established [33]–[35]. An association of repetitive sequence with synteny break points in Caenorhabditis has also been identified [12], [36]. This may be an indirect association, if repetitive sequences represent derivatives of TEs or are generated by TE insertions, or a direct association if repetitive sequences induce ectopic recombination between repeats [36].

Both putative gene duplications identified in this study were associated with intronic transposon insertions, and one was also associated with the repeat element HcRep. Studies have suggested that TEs might be enriched within or flanking environmental response genes, such as the cytochrome P450 family [37]. Genomic plasticity would be predicted to be advantageous at these loci, as it would facilitate adaptive response to changes in the environment. Consistent with this hypothesis, a gene duplication associated with an intronic mariner transposon insertion and the repeat element HcRep was identified at a P-glycoprotein locus in this study. A TE insertion was observed in intron 5 of hc-bh4e20-13, which may also be an environmental response gene: the putative orthologue in C. elegans, ttx-7, encodes a myo-inositol monophosphatase required for normal thermotaxis and chemotaxis to sodium [38]. However, a retrotransposon-associated gene duplication was also identified involving the orthologue of C. elegans folt-1, a folate transporter, and intronic TE insertions were identified in two H. contortus genes more likely to have constitutive functions: orthologues of the C. elegans mec-7 (a β-tubulin) and air-2 (a serine/threonine protein kinase).

Implications for the H. contortus genome project

This work indicates that the previous prediction of the genome size of H. contortus at 53 Mb may be an underestimate [39]. The C. elegans genome is 100 Mb and if the parasite genome has a similar gene complement, a gene density and size differing from the model worm by a two to three fold magnitude would be suggestive of a ∼200–300 Mb genome. This has obvious implications for the genome project, but may in part explain the current difficulties with assembly (Gilleard and Berriman, unpublished data).

Nematode genomes are evolving rapidly. Comparisons of C. elegans and C. briggsae genomes relative to mouse and human genomes (the former pair diverged ∼80–110 million years ago, the latter ∼75 million years ago), showed the nematodes have fewer 1∶1 orthologue pairs, more genes lacking matches in both species, a nearly three-fold higher nucleotide substitution rate and a dramatically higher chromosomal rearrangement rate [12]. C. elegans and H. contortus are estimated to have diverged 400 million years ago [21] and the impact of the H. contortus adaptation to parasitism on the (potentially highly plastic) nematode genome is unknown, but it was predicted that the retention of a conserved genetic core relating to essential biological processes would facilitate a comparative bioinformatic approach for gene discovery and annotation [2]. In this study, we found that 97.5% of genes had detectable homologues in C. elegans and 60% had clear orthologues. This is higher than anticipated from EST comparisons and suggests that comparative sequence analysis between the two species will be a powerful approach for gene annotation. Although global positional information of genes in C. elegans will be of limited use for finding orthologues in the parasite due to the high rate of intra-chromosomal rearrangements, homologous genes do appear to reside on the same chromosomes frequently, and where present, local regions of microsynteny can be used as supporting evidence of orthologous relationships.

In summary, the H. contortus transcriptome has been sequenced using Illumina technology and this pilot survey of 590 kb genomic sequence suggests RNA-seq will be a useful technique to annotate the H. contortus genome. The results also suggest the close phylogenetic relationship of H. contortus and C. elegans will also facilitate a comparative genomics approach, which will prove particularly useful for annotation of conserved genes with a low level of expression in the parasite.

Materials and Methods

H. contortus maintenance and culturing

All experimental procedures described in this manuscript were examined and approved by the Moredun Research Institute Experiments and Ethics Committee and were conducted under approved British Home Office licenses in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986. The Home Office license number is PPL 60/03899 and experimental IDs for these studies were E34/09 and E36/09. Experimental infections were performed by oral administration of 5000 L3 of the H. contortus MHco3 (ISE) isolate [15] into 4- to 9-month-old lambs that had been reared and maintained indoors under parasite-free conditions. 21-day-old adult worms were removed at post-mortem using an agar/mesh flotation method described in Jackson and Hoste [40] then rinsed and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

BAC library construction

Two BAC libraries were prepared by partially digesting PFGE plugs prepared from H. contortus larvae with Sau3AI or Apo1, respectively. High molecular weight DNA was resolved by CHEF gel electrophoresis and recovered by electroelution before ligating into BamHI- or EcoR1-cut pBACe3.6, respectively. The ligation was electroporated into DH10B cells (Invitrogen), plated, robotically picked and arrayed into 384 well microtitre plates before being replicated and tested for absence of bacterial and phage contamination.

BAC sequencing and assembly

Seven BACs were chosen for sequencing from the 20,828 BAC end-sequences of the ongoing genome project and small insert libraries (2–4 kb) were constructed in Sma I digested pUC18. ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator (Applied Biosystems) forward and reverse plasmid end sequences were generated using an ABI3730 capillary sequencer and then assembled and manually finished using Phrap and Gap4, respectively, from the Staden package.

Annotation and nomenclature

Two genomic sequences were annotated. The first consisted of a 409 kb contig, assembled as the consensus of five overlapping BAC insert sequences: haemapobac13c1, haemapobac7n11, haembac15g16, haembac18h7 and haembac18g2. Genetic analysis using microsatellite markers within this contig has shown it to be derived from the X chromosome [15]. The second sequence was a non-contiguous 181 kb BAC insert, BHA4E20Ge02.q2ky012. In this paper, these sequences are referred to as the X-linked contig and BAC BH4E20 respectively. All annotated genes are named ‘hc’ for H. contortus, followed by an identifier for the BAC insert sequence they are located on, followed by a number e.g. hc-13c1-1.

The subset of H. contortus putative orthologues of C. elegans genes were identified using the following criteria: the predicted polypeptide encoded by each putative orthologue had greater than 45% amino acid identity to a C. elegans protein, over greater than 80% of its length, and no sequence with higher identity to the C. elegans protein was present in the H. contortus shotgun assembly contig databases. Two neighbouring genes on the X-linked contig, hc-13c1-5 and hc-13c1-4, were both homologous with C. elegans folt-1 (50% and 48% amino acid identity, respectively), and may represent a recent duplication event. The structure of both H. contortus genes was essentially the same, so to avoid repetition in the comparison of gene structure between species, only hc-13c1-5 was included in the analysis. Three genes were included in the subset of orthologues due to conserved microsynteny, although their amino acid identity was below the conservative cut-off. Distance trees were built from BLAST pairwise alignments of the top 100 hits in the NCBI non-redundant protein databases to each H. contortus polypeptide to confirm each parasite gene clustered with its putative C. elegans orthologue.

cDNA library preparation and sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from a frozen pellet of 500 µl mixed sex adult worms using a standard Trizol (Invitrogen, 15596-026) protocol. The quality and quantity of the total RNA yield was assessed with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent). mRNA was isolated from 50 µg total RNA with magnetic beads (FastTrack MAG mRNA Isolation Kit, Invitrogen, K1580-01) according to the manufacturer's protocol and eluted in 35 µl RNase-free water. The mRNA was quantified with a NanoDrop 3300 Fluorospectrometer (Thermo Scientific). mRNA (0.5–1 µg) was fragmented with RNA Fragmentation Reagents (Ambion, AM8740): 31.5 µl mRNA was heated at 70°C with 3.5 µl 10× Fragmentation Buffer for 5 minutes, before adding 3.5 µl Stop Buffer. The fragmented mRNA was precipitated with 3.5 µl NaOAC pH 5.2, 2 µl glycogen and 100 µl 100% ethanol and incubated at −80°C for 30 minutes. Following centrifugation at 14000 rpm at room temperature for 15 minutes, the supernatant was removed and the pellet washed with 1 ml 70% ethanol in DEPC-treated water, then vortexed and centrifuged at 14000 rpm at room temperature for 10 minutes. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was air-dried for up to 30 minutes then re-suspended in 10.5 µl RNase-free water. First-strand and second-strand cDNA were synthesized according to the manufacturer's protocol (Superscript Double-stranded cDNA Synthesis Kit, Invitrogen) but with 3 µg/µl random hexamer primers (Invitrogen). The cDNA was cleaned using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen).

Sequencing libraries for the Illumina GA II platform were constructed from the cDNA, with end-repair with Klenow polymerase, T4 DNA polymerase and T4 polynucleotide kinase (to blunt-end the DNA fragments). A single 3′ adenosine moiety was added to the cDNA using Klenow exo- and dATP. Illumina adapters were ligated onto the repaired ends of the cDNA and gel-electrophoresis was used to separate library DNA fragments from unligated adapters by selecting cDNA fragments between 200 and 250 bp in size. Ligated cDNA fragments were recovered following gel extraction and libraries were amplified by 18 cycles of PCR with Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes Reagents).

The efficacy of each stage of library construction was ascertained in a quality control step that involved measuring the adapter-cDNA on an Agilent DNA 1000 chip. For each library, paired end 76 bp reads were produced from a single lane of an Illumina GA flowcell according to manufacturer's protocol.

RNA-seq analysis

Transcriptomic reads were mapped to the reference genomic sequences using BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner; [41]) and processed into BAM format using SAMtools [42]. Sorted and indexed BAM files were opened and viewed as stacks of paired reads over genomic sequence in Artemis [43], [44] (Figure S1).

To permit the identification of genes trans-spliced to SL1 and SL2, all transcriptomic reads containing published H. contortus SL1 or SL2 sequences (accession numbers Z69630 and AF215836 respectively) were extracted and the SL sequence was removed. There is a family of SL2 sequences in C. elegans, and the same may be true in H. contortus, so a single base pair mismatch from the published sequence was tolerated. The trimmed reads were aligned to the reference genomic sequences with BWA as two separate groups (depending on the SL sequence). The SL1 and SL2 BAM files were sorted and indexed with SAMtools and opened directly in Artemis to view the trimmed reads aligned to the annotated genomic sequences.

Bioinformatics

Sequence similarity searches of predicted H. contortus genes and their conceptual translations were performed using BLAST at the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) and C. elegans Wormbase (www.wormbase.org/db/searches/blast_blat). The gene prediction software ‘Genefinder’ was run on the X-linked contig using C. elegans parameters (www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_elegans/GENEFINDER). Conserved synteny was assessed by aligning the H. contortus X-linked contig and BAC BH4E20 with C. elegans chromosome X and chromosome I respectively, with the Artemis Comparison Tool (ACT) [45], [46].

For the analysis of BAC end-sequences, a BLASTx search of Wormpep with the 20,828 paired sequences (each end of 10,414 BAC insert sequences) in the H. contortus BAC end database was undertaken. The locus of the best-matched C. elegans gene for every hit with P<0.01 was recorded, before matching up each BAC end with its mate pair and comparing the loci of the putative homologues (Table S1).

Supporting Information

Annotation of the H. contortus genome with RNA-seq. A typical Artemis screen shot with transcriptome reads from the highly expressed gene hc-bh4e20.16 aligned to genomic sequence. Grey lines connect paired reads.

(TIF)

H. contortus BAC inserts with matches (P<0.01) to C. elegans proteins at each end.

(DOC)

12 transposable elements identified in 590 kb genomic sequence.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alison Morrison and Dave Bartley at the Moredun Research Institute for provision of parasite material. James Wasmuth is thanked for useful comments on the manuscript. The sequencing data in this study were produced by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and are available for download from www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/downloads/helminths/haemonchus-contortus.html. The Genefinder results were produced by Marie-Adele Rajandream and Avril Coghlan and are also available from the download site.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have read the journal's policy and have the following conflicts. The study received some funding support from Quality Meat Scotland (QMS), English Beef and Sheep Sectors (EBLEX), Hybu Cig Cymru (HCC) and Pfizer Animal Health PLC. This does not alter the authors' adherence to all the PLoS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Funding: RL was funded by Quality Meat Scotland (QMS), English Beef and Sheep Sectors (EBLEX), Hybu Cig Cymru (HCC) and Pfizer Animal Health PLC. The sequencing was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number WT 085775/Z/08/Z). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Couthier A, Smith J, McGarr P, Craig B, Gilleard JS. Ectopic expression of a Haemonchus contortus GATA transcription factor in Caenorhabditis elegans reveals conserved function in spite of extensive sequence divergence. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;133:241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilleard JS. The use of Caenorhabditis elegans in parasitic nematode research. Parasitology. 2004;128(Suppl 1):S49–S70. doi: 10.1017/S003118200400647X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knox DP, Redmond DL, Newlands GF, Skuce PJ, Pettit D, et al. The nature and prospects for gut membrane proteins as vaccine candidates for Haemonchus contortus and other ruminant trichostrongyloids. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:1129–1137. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeJambre LF, Windon RG, Smith WD. Vaccination against Haemonchus contortus: performance of native parasite gut membrane glycoproteins in Merino lambs grazing contaminated pasture. Vet Parasitol. 2008;153:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaminsky R, Ducray P, Jung M, Clover R, Rufener L, et al. A new class of anthelmintics effective against drug-resistant nematodes. Nature. 2008;452:176–180. doi: 10.1038/nature06722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilleard JS. Understanding anthelmintic resistance: the need for genomics and genetics. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1227–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prichard R. Genetic variability following selection of Haemonchus contortus with anthelmintics. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:445–453. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(01)01983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolstenholme AJ, Fairweather I, Prichard R, Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Sangster NC. Drug resistance in veterinary helminths. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chain PS, Grafham DV, Fulton RS, Fitzgerald MG, Hostetler J, et al. Genomics. Genome project standards in a new era of sequencing. Science. 2009;326:236–237. doi: 10.1126/science.1180614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The C. Celegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duret L, Mouchiroud D. Expression pattern and, surprisingly, gene length shape codon usage in Caenorhabditis, Drosophila, and Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4482–4487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein LD, Bao Z, Blasiar D, Blumenthal T, Brent MR, et al. The genome sequence of Caenorhabditis briggsae: a platform for comparative genomics. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsch M, Long M. Intron-exon structures of eukaryotic model organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3219–3228. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spieth J, Lawson D. Overview of gene structure. WormBook. 2006:1–10. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.65.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redman E, Grillo V, Saunders G, Packard E, Jackson F, et al. Genetics of mating and sex determination in the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Genetics. 2008;180:1877–1887. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.094623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rufener L, Maser P, Roditi I, Kaminsky R. Haemonchus contortus acetylcholine receptors of the DEG-3 subfamily and their role in sensitivity to monepantel. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000380. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redmond DL, Knox DP. Haemonchus contortus SL2 trans-spliced RNA leader sequence. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;117:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laughton DL, Amar M, Thomas P, Towner P, Harris P, et al. Cloning of a putative inhibitory amino acid receptor subunit from the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Receptors Channels. 1994;2:155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callaghan MJ, Beh KJ. Characterization of a tandemly repetitive DNA sequence from Haemonchus contortus. Int J Parasitol. 1994;24:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grillo V, Jackson F, Gilleard JS. Characterisation of Teladorsagia circumcincta microsatellites and their development as population genetic markers. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;148:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoekstra R, Criado-Fornelio A, Fakkeldij J, Bergman J, Roos MH. Microsatellites of the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus: polymorphism and linkage with a direct repeat. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;89:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanfleteren JR, Van de PY, Blaxter ML, Tweedie SA, Trotman C, et al. Molecular genealogy of some nematode taxa as based on cytochrome c and globin amino acid sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1994;3:92–101. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1994.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkinson J, Mitreva M, Whitton C, Thomson M, Daub J, et al. A transcriptomic analysis of the phylum Nematoda. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1259–1267. doi: 10.1038/ng1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coghlan A, Wolfe KH. Fourfold faster rate of genome rearrangement in nematodes than in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2002;12:857–867. doi: 10.1101/gr.172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghedin E, Wang S, Spiro D, Caler E, Zhao Q, et al. Draft genome of the filarial nematode parasite Brugia malayi. Science. 2007;317:1756–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.1145406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guiliano DB, Hall N, Jones SJ, Clark LN, Corton CH, et al. Conservation of long-range synteny and microsynteny between the genomes of two distantly related nematodes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0057. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-10-research0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillier LW, Miller RD, Baird SE, Chinwalla A, Fulton LA, et al. Comparison of C. elegans and C. briggsae genome sequences reveals extensive conservation of chromosome organization and synteny. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ranz JM, Casals F, Ruiz A. How malleable is the eukaryotic genome? Extreme rate of chromosomal rearrangement in the genus Drosophila. Genome Res. 2001;11:230–239. doi: 10.1101/gr.162901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumenthal T, Gleason KS. Caenorhabditis elegans operons: form and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:112–120. doi: 10.1038/nrg995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian W, Zhang J. Evolutionary dynamics of nematode operons: easy come, slow go. Genome Res. 2008;18:412–421. doi: 10.1101/gr.7112608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graber JH, Salisbury J, Hutchins LN, Blumenthal T. C. elegans sequences that control trans-splicing and operon pre-mRNA processing. RNA. 2007;13:1409–1426. doi: 10.1261/rna.596707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu C, Oliveira A, Chauhan C, Ghedin E, Unnasch TR. Functional analysis of putative operons in Brugia malayi. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bessereau JL. Transposons in C. elegans. WormBook. 2006:1–13. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.70.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caceres M, Ranz JM, Barbadilla A, Long M, Ruiz A. Generation of a widespread Drosophila inversion by a transposable element. Science. 1999;285:415–418. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duret L, Marais G, Biemont C. Transposons but not retrotransposons are located preferentially in regions of high recombination rate in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2000;156:1661–1669. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.4.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coghlan A, Wolfe KH. Fourfold faster rate of genome rearrangement in nematodes than in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2002;12:857–867. doi: 10.1101/gr.172702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen S, Li X. Transposable elements are enriched within or in close proximity to xenobiotic-metabolizing cytochrome P450 genes. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanizawa Y, Kuhara A, Inada H, Kodama E, Mizuno T, et al. Inositol monophosphatase regulates localization of synaptic components and behavior in the mature nervous system of C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3296–3310. doi: 10.1101/gad.1497806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leroy S, Duperray C, Morand S. Flow cytometry for parasite nematode genome size measurement. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128:91–93. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson F, Hoste H. In vitro screening of plant resources for extra-nutritional attributes in ruminants: nuclear and related methodologies. In: Vercoe PE, Makkar HPS, Schlink AC, editors. In Vitro Methods for the Primary Screening of Plant Products for Direct Activity against Ruminant Gastrointestinal Nematodes. Springer Netherlands; 2010. pp. 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, et al. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carver T, Bohme U, Otto TD, Parkhill J, Berriman M. BamView: viewing mapped read alignment data in the context of the reference sequence. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:676–677. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carver TJ, Rutherford KM, Berriman M, Rajandream MA, Barrell BG, et al. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3422–3423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abbott JC, Aanensen DM, Rutherford K, Butcher S, Spratt BG. WebACT - an online companion for the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3665–3666. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Annotation of the H. contortus genome with RNA-seq. A typical Artemis screen shot with transcriptome reads from the highly expressed gene hc-bh4e20.16 aligned to genomic sequence. Grey lines connect paired reads.

(TIF)

H. contortus BAC inserts with matches (P<0.01) to C. elegans proteins at each end.

(DOC)

12 transposable elements identified in 590 kb genomic sequence.

(DOC)