Abstract

I thank the Society for Urban Anthropology for the Anthony Leeds Book Prize. The award gives me special pleasure because I think of myself primarily as an urban anthropologist. I was trained in “peasant studies” as a student of Eric Wolf’s in the late 1970s and early 1980s eager to conduct participant-observation fieldwork on the revolutionary movements taking place in Central America in those decades. It was a hopeful - even inspiring - moment in history at my doctoral fieldwork theme/sites: the agrarian reform in the Amerindian Moskitia territory of Sandinista Nicaragua (1979-80, 1984), guerrilla warfare in an FMLN-controlled territory in El Salvador (1981), and farmworker organizing on a United Fruit Company plantation enclave spanning the Costa Rica/Panama Caribbean border (1982-1984). During these exciting years of fieldwork, however, I found myself longing to return to my hometown to conduct ethnography on the same themes that I was witnessing in the countryside of Central America: the political mobilization/demobilization of class struggle in the context of racialized ethnicity and extreme social inequality. Consequently, while writing up my dissertation (Bourgois 1989), I moved to East Harlem two dozen blocks from where I had grown up in New York City to document what I came to call “US inner-city apartheid.” That was in March of 1985 and ever since, my work has been primarily dedicated to understanding urban social inequality.

Our punitive era

I began the fieldwork for Righteous Dopefiend in the fall of 1994 by befriending a community of some two dozen heroin injectors and crack smokers surviving under the overpasses of a tangle of freeways six blocks from where I lived in San Francisco. The full force of the Reagan era cutbacks from the 1980s had trickled down to the street, shredding the already rachitic U.S. welfare safety net. Inner-cities were gentrifying (especially those linked to the epicenters of global finance capital such as San Francisco). The former skid row habitat for the unstable urban poor - cheap single residency hotels - was being converted into multi-million dollar condominiums. Urban police forces had not yet systematized, routinized and replicated their zero-tolerance enforcement, harassment/incarceration dragnets (Wacquant 2009), and homelessness, consequently, was at its most visible. Bourgeois residents like me (no pun intended) could not walk down a block or drive up a freeway entrance ramp in downtown San Francisco without being solicited for spare change. For the next twelve years, with the help of my coauthor Jeff Schonberg and several additional ethnographic team members,1 we followed the social network of homeless addicts in my neighborhood.

This span of years 1994-2007 was a terrible time for the poor in the United States and throughout much of the rest of the world: 1) The punitive version of neoliberalism had fully consolidated in the United States and was achieving hegemony - even if unevenly (Harvey 2005) - across much of the globe. 2) The U.S. War on Terror was inaugurated with great bloodshed, routinizing the curtailment of civil rights. 3) The recession of 2007-2009 struck, accelerating the ongoing public subsidy of high finance and reinforcing the bulwark for the long-term rise in income inequality that has been occurring since the 1970s (McCall and Percheski 2010).

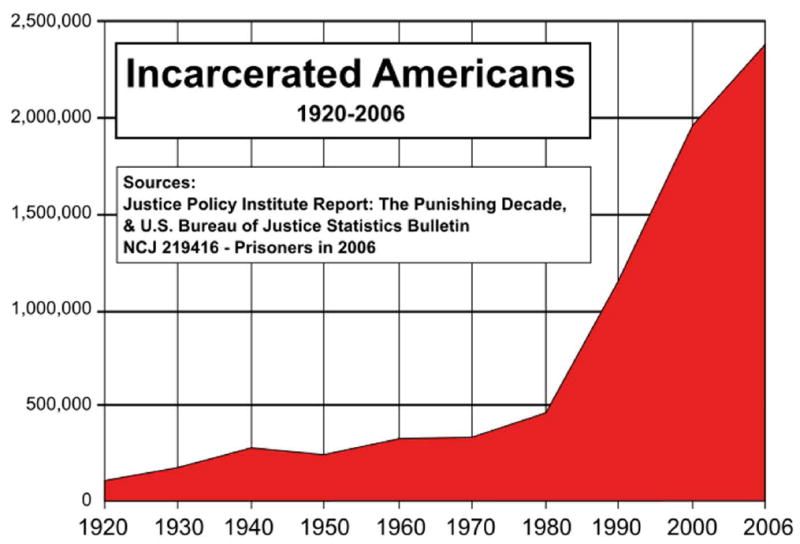

Indigent addicts in the United States in the 2010s find themselves trapped in an “abusive carceral cycle.” Imprisonment has become the most aggressive and well-funded de facto housing and drug treatment policy for the poor. The prison population increased by over half a million men and women during our fieldwork years and many, if not most, of these new inmates were addicted to drugs and homeless (or unstably housed) at the time of their arrest. Their criminal record, exacerbated by a low skill level imposed by years of forced idleness in a purposefully hostile carceral environment devoid of rehabilitative programs (Conover 2000), condemns them to chronic unemployment upon their release from prison. Many if not most cycle immediately back into homelessness and do not find stable shelter again until they are re-incarcerated.

The goal of Righteous Dopefiend is to render more visible from an analytical, emotional and political perspective the human cost of the punitive version of neoliberalism that guides U.S. public policy. It is a narrative account documenting twelve years in the lives of a cast of characters who are bonded by a moral economy of sharing and mutual betrayal.

Team ethnography

Initially, we thought it would be difficult to establish a non-intrusive and ethical ethnographic relationship with the principle characters in our book given the fragility of their survival strategies and the everyday urgency of their drug use. They did not share our concern, however, and almost immediately integrated us non-problematically into their scene. As veteran survivor/hustlers, they recognized us as a potential resource, and most of them enjoyed being the center of our attention. They allowed us to accompany them as they scrambled for money, food, shelter, drugs, and community while fleeing the police in their race to flood their bodies every day several times a day with heroin, alcohol and cocaine. Sometimes they coddled us as exotic, high status outsiders and invited us on visits to estranged family members, scavenging expeditions, burglaries, and outings to the beach. They laid out blankets for us on the special occasions when we slept over in their encampments. They introduced me to newcomers and transients possessively as “This is my professor I was telling you about…” and Jeff was “…my photographer…”

As academics we tend to misread the real world stakes and ethical quandaries of our research. Anthropological fieldwork ethics do not need to be in substantial contradiction with commonsensical, spontaneous human ethics. In the case of the homeless for example, the best way to document the inadequacy of social services is to act as an “ethnographic accompagnateur” - to borrow a public health term (Behforouz, Farmer and Mukherjee 2004) - in other words to assist, accompany and document. Consequently, we spent long hours attempting to facilitate (often unsuccessfully) their access to hospital emergency rooms, drug treatment centers, social service offices, community-based clinics, and subsidized housing programs.

Ending an ethnographic project often feels like a betrayal of friendship, and both Jeff and I found it difficult to leave the “field.” We still feel guilty about it. This emotional quandary is inherent to our methodology and is exacerbated when one does fieldwork close-to-home across steep social power gradients. The two of us were also in close companionship as ethnographers and co-authors: We wrote the first three drafts of the book side by side. We composed the text together: copying, pasting, editing and re-editing from some 400 separate files of fieldwork notes and transcribed conversational-style interviews - about 5,000 pages of raw material. Our unruly mountain of notes, transcripts and photographs kept growing, however, even after the University of California Press legitimately insisted that we cut our text by forty percent. Our problem was that we kept interrupting our writing to run down to the corner and “check on the guys.” Inevitably, we would come back with a half dozen more pages of new fieldwork notes, a “strategically targeted” follow-up interview (or two), and a full roll (or two) of freshly shot film.

We eventually had to force ourselves to disengage with the “people, places and things” - as they say in the drug treatment community - of our fieldwork scene in order to complete the book. I left San Francisco for Philadelphia in the summer of 2007 and undertook yet two more drafts (or was it three… or four?), sending the material back and forth to Jeff for his comments and re-edits, and seeking help from Laurie Hart, my partner, in order to clarify theoretical passages on key topics: “lumpen abuse”, “class as a subjectivity”, “familial psychodynamics and trauma”, “homosocial homophobia,” and the history of photographic representation.

The practical artisanal value of conducting fieldwork as a team is underappreciated in anthropology. Collaboration allows ethnographers to explore their positionality, appreciate the partiality of perceived truths, and triangulate findings, (i.e. compare notes, collect alternative perspectives, and strategize follow-up fieldwork). Daily life among homeless injectors is often emotionally challenging. They are embroiled in a politically-imposed suffering that manifests in an everyday interpersonal violence of intimate aggression and betrayal that can be destructive for them and disorienting and alienating for an outsider. Conducting ethnography side-by-side with a friend/colleague enables one to relax, concentrate more, and brainstorm during the very process of fieldwork itself. In the midst of often overwhelming or draining events going on all around us, Jeff and I were able to step aside together and find a private spot to vent, strategize, joke and/or simply relax with one another. This enabled us to stay in the field longer, feel safer, act more ethically, and persevere more productively than had we been working alone. Perhaps most importantly working as a team is also more fun.

Photo-ethnography

About nine months after beginning the fieldwork I realized that text was not going to be enough to convey the routine violence of survival on the street as well as well as its playful - at times ecstatic - sociality. I asked Jeff to join the project as a photographer, thinking it would be a one-or-two year collaboration. It took us several years, however, to understand how to integrate photography into an ethnographic project of this kind producing what we now call a “photo-ethnography”.

I find the poetry, philosophy and creativity of street talk beautiful. My ethnographic aesthetics and analysis focuses on tape recording conversations that I guide to specific themes that are subsequently written up as fieldnotes. I do not have the gift of thinking visually the way Jeff does. He is able to observe, participate, audio record, and photograph simultaneously without losing concentration. Soon Jeff’s fieldnotes and recordings were just as good as his photographs and he became as much of an ethnographer as he is a photographer. His photographic gaze gives his filed notes a fine-grained intimate visual detail. Somehow he also manages to take intimate pictures without intimidating or interrupting social interaction. Initially I was crassly utilitarian in my relationship to photography and urged Jeff to be more didactically linear with his pictures and to shoot in color. Luckily, he ignored me. Color photographs would have pushed this kind of documentation over the top. Color also would have left out the references to the history of a form of art that allows viewers to be made aware that the reality they are viewing has been purposefully edited, framed, and contextualized to make a point.

To avoid objectifying or dumbing-down the photographs selected to be in the book we chose not to use captions. But neither did we trust them to stand on their own. The subject of poverty and substance abuse, not to mention HIV, crime, racialized ethnicity, childhood trauma, non-normative sexuality, and interpersonal violence, is subject to moral judgementalism. Consequently, we embedded Jeff’s pictures strategically in the text to encourage humane as well as critical analytical readings/viewings and to diminish ethno/class-centric and righteously normative projections. His photographs are alternately beautiful, jarring, evocative and documentary. We wrapped them in text (consisting of fieldnotes, dialogues, ethnographic analysis) that is alternately theoretical, narrative, evocative, policy-oriented. Our hope is that the merger of the mediums of photography and anthropology can convey more than the sum of the parts methodologically, theoretically and representationally. By imbuing social science analysis with the emotional, documentary and aesthetic power of photo-ethnography we hope to open intellectual debate to a wider audience and to promote practical engagement.

This shooting gallery was our social network’s primary injection locale for several months when off-the-books day labor was temporarily available selling Christmas trees on a nearby vacant lot. Jeff describes the moment he took the picture in a fieldnote that appears in a chapter on the legal income generating strategies that had turned many of the homeless into inexpensive, just-in-time day laborers for fly-by-night seasonal employers.

This kind of artful, deliberately aesthetic photograph standing alone without an accompanying text can devolve into sheer voyeurism. Jeff’s fieldnotes and the overall arguments of the book, however, alert readers to the logic for injecting in the midst of filth and prevent a pathologizing gaze: The zero-tolerance War on Drugs has turned filthy nooks and crannies into the safest refuges for homeless injectors even if they are also incubators for propagating infectious diseases from the perspective of public health. On a more practical level the image conveys viscerally to public health and clinically-based readers the disjunction between hypersanitary HIV-prevention outreach messages and the reality of street-level addiction.

The image also reinforces the matter-of-factness of a fieldnote that might otherwise sound like hyperbole, hallucination, or propaganda. It is located in our chapter on deindustrialization. The details of the photo highlight how the “trickle-down benefit” to the indigent of the booming, high tech digital globalized economy of the San Francisco Bay Area‘s Silicon Valley is limited to discarded computer monitors that serve here as seats in a shooting gallery. This chapter argues for re-framing Marx’s concept of class through a redefinition of the problematic, but creative category of “lumpen” to develop a “theory of lumpen abuse under punitive neoliberalism.” To do this, we draw from Foucault’s understanding of subjectivity and biopower, Bourdieu’s concepts of symbolic violence and habitus, Primo Levi’s insights on the invisibility of Holocaust-like gray areas in routine daily life and we re-define the lumpen as those vulnerable populations for whom biopower (the state-mediated forces and discourses of disciplinary modernity) has become abusive rather than productive. Our era’s economy, its structures of service provision, and the symbolic violence of individual achievement and free market efficiency condemns increasingly large proportions of the transgressive poor to processes of lumpenization, which decimate bodies and amplify suffering.

Good-enough public anthropology: homelessness, poverty and addiction at the museum

The fledgling school of “public anthropology” attempts to bring the participant-observation methodological tools and theoretical insights of our discipline to bear on the urgent social challenges of our era. Ideally, public intellectuals avoid becoming embroiled in the narrow details of partisanship or political positioning, so as to document the larger social-structural patterns that can be made visible through reflective, calm theoretical inquiry. The goal is to communicate to a wider public without dumbing-down or sanitizing an uncomfortable analysis. It requires entering policy debates and devoting energy to accessing wider media forums than those offered by our peer-review journals and university press publishers.

In the spirit of public anthropology we organized a photo-ethnographic exhibit at the Museum of Anthropology and Archeology at the University of Pennsylvania as well as an audio-visual installation at the Slought Foundation, an alternative art gallery, in Philadelphia. Old-fashioned, dusty-halled anthropology museums are beautiful, calm, reflective spaces. They offer a valuable but underutilized forum for heightening the visibility of ethnographic work on public issues. The aesthetic medium of museum display enables thoughtful audiences, who are different from those who buy and read academic books, to confront, evaluate and experience viscerally the world’s “everyday emergencies” (Taussig 1986).

Good museum curators translate complex historical and social ideas into a balance of images with minimal text. Our museum co-curator (Kathleen Quinn) transformed the jumble of text and photographs we initially provided into an elegant succinct display that covered six central theoretical and topical themes we had wanted to emphasize. She selected a long hallway gallery so that a walk through the exhibit space might approximate a quasi-ethnographic experience of homelessness, addiction, and war on drugs:

The political economy of the lumpenization of the former industrial working class whose descendants make up the bulk of the indigent in the urban United States.

The virulence of ethnic antagonism on the street, especially between whites and African-Americans, as well as its institutional reinforcement by law enforcement, social services, and everyday U.S. racism.

The contradiction between the War on Drugs and the delivery of public health and social services.

The unintended negative consequences of social services and drug treatment that renders biopower abusive under punitive neoliberalism, exacerbating suffering.

The cross-generational familial roots and ongoing interpersonal psychodyamics of violence, intimate betrayal and loss among friends, lovers, and kin of the homeless.

And finally, the moral economy of gift-giving and mutual solidarity that propagates infectious diseases but also prolongs the survival, bonding, and hierarchies of street-based micro-communities of addicted bodies self-styled as righteous dopefiends.

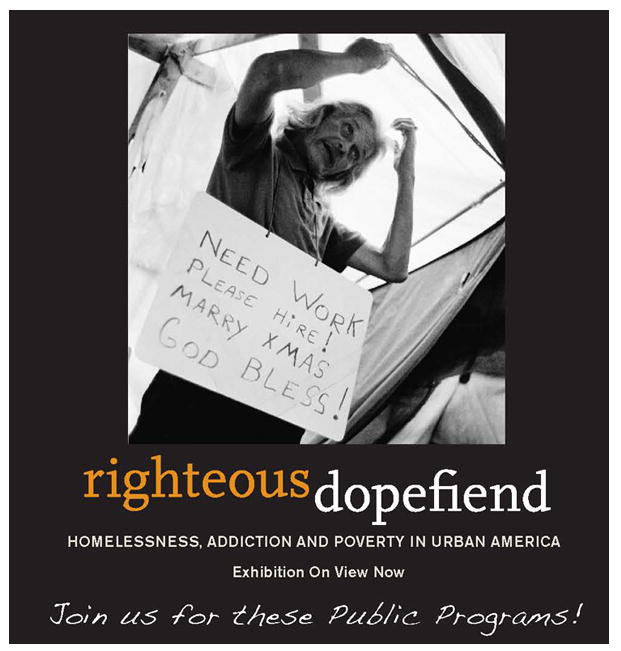

Anthropology museums must raise millions of dollars from private donors each year to stay open. This forces them, unlike university presses, to invest in effective public relations. The Museum’s public relations staff consequently can be another effective resource for broadcasting the message of contemporary cultural anthropology to broader audiences. For example, on billboards above two of the major freeways leading into Philadelphia, the museum placed Jeff’s “homeless Vietnam Vet photograph” of Hank waving the American flag in his ramshackle encampment; the words “Homelessness, Poverty and Addiction at the University of Pennsylvania Museum” emblazoned across his emaciated back. The billboards pushed a 14-second critique of urban dualism and invisibilized inner-city poverty into an artery of suburban public space in a way I had not thought possible. The museum ran advertisements in local weeklies including one during the Christmas holidays with Jeff’s photo of Hank hailing passersby holding up a misspelled panhandling sign: “Marry Christmas, need work, God Bless.”

The museum extended the exhibit for an extra year and most interesting to us has been the way community groups and homeless and addiction services organizations use the space, bringing their clients/patients/inmates for visits and reflection sessions. Perhaps, the most moving comments we have received have been from the family members of deceased heroin injectors and crack smokers. There are few public, safe, respectful, serious and forgiving spaces that acknowledge the unresolved anger, quiet confusion, and frustrated longing, left among close kin by addicted loved ones who have died (Garcia 2011). Most family members are forced to mourn their lost siblings, children, or parents in silence - if not shame - and they remain an invisible community. The exhibit seems to allow them to come forward and situate in history and in public policy their family’s solitary painful experience in a larger shared community.

The more avant-garde exhibition space of our initially simultaneous multimedia installation, “Righteous Dopefiend: Voices of the Homeless” reached fewer viewers but it introduced us to the value and untapped potential of multi-media, especially audio, installations of ethnographic material. We prepared audio loops of excerpts from our hundreds of hours of recordings. This foray into audio-editing made us realize how much more the sound of voices communicates about racialized ethnicity, class, sex-and-gender, ethnographic rapport, suffering and human emotion than do transcriptions of those same voices frozen into print.

Anthropology straddles the boundaries of the humanities and the social sciences, generating a scholarly space for critical epistemologies. Over the past century we differentiated ourselves from other social science and humanities approaches through our dedication to participant-observation ethnographic fieldwork methods that valorize participatory and subjective engagement with our data. Fieldwork requires long-term interpersonal contact with the people and processes we research. We are forced to go out into the messy, scary real world and to straddle social power divides. We often purposefully violate de facto apartheid divisions of social class, ethnicity and normativity that structure many, if not all, social formations.

We cannot escape seeing, feeling, and empathizing with the people we study. It impels us to raise problematic questions and confronts us ethically and practically with the public stakes of our writing. When our fieldwork methodology is combined with our basic good-enough heuristic principle of cultural relativism, the result can be inherently destabilizing to power, privilege, and fossilized common sense. Cultural relativism has been anthropology’s foundation for combating ethnocentrism and valorizing diversity. It also introduces an analytical space for a humble, (also good-enough) critical self-reflection that is often missing in other academic disciplines. The hermenutics of generosity that cultural relativism implies is an antidote to righteousness - even though it often prompts some ethnographers to sanitize their data and to bear only good news about the always-worthy people they study. Nevertheless, as anthropologists we benefit from distrusting our capacity to see, feel, and report authoritatively.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Acknowledgments

Research support was provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: DA 010164. Comparative and background data was supported by NIH grants DA027204, DA027689, DA27599 and the California HIV/AIDS Research Program ID08-SF-049. George Karandinos edited the multiple drafts and the photograph of the shooting gallery is Jeff Schonberg’s copyright.

Footnotes

Over the years, formal and informal collaborators on the ethnographic team included (in alphabetical order): Maxwell Burton, Dan Ciccarone, Laurie Hart, Mark Lettiere, Ann Magruder, Fernando Montero, Joelle Morrow, Charles Pearson, and Jim Quesada.

References cited

- Behforouz Heidi, Farmer Paul, Mukherjee Joia. From Directly Observed Therapy to Accompagnateurs: Enhancing Aids Treatment Outcomes in Haiti and in Boston. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;38(Supplement 5):S429–S436. doi: 10.1086/421408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois Philippe. Ethnicity at Work: Divided Labor on a Central American Banana Plantation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Conover Ted. Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing. New York: Random House; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Angela. Reading Righteous Dopefiend with My Mother. Anthropology Now. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McCall L, Percheski C. Income Inequality: New Trends and Research Directions. Annual Review of Sociology. 2010;36:329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Taussig Michael T. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant Loïc. Prisons of Poverty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]