Abstract

CodY is a global transcriptional regulator that is known to control, directly or indirectly, expression of more than one hundred genes and operons in Bacillus subtilis. Using a combination of mutational analysis and DNase I footprinting experiments, we identified two high affinity CodY-binding sites that contribute to repression of the ybgE gene and appear to act independently. One of these sites, located 80 bp downstream of the transcription start site, accounted for the bulk of ybgE repression. Using in vitro transcription experiments, we demonstrated that in the presence of CodY a shorter-than-expected ybgE transcript was synthesized that terminates at the downstream CodY-binding site. Thus, CodY binding to the downstream site represses transcription by a roadblock mechanism. Similar premature termination of transcription was observed for bcaP and yufN, two other CodY-regulated genes with binding sites downstream of the promoter. In accord with the roadblock mechanism, CodY-mediated repression at downstream sites was partly relieved if transcription-repair coupling factor Mfd was inactivated.

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis, branched-chain aminotransferase, CodY-binding sites, gene expression, roadblock repression

INTRODUCTION

CodY is a global transcriptional regulator in Bacillus subtilis that controls expression of many metabolic genes, most of them negatively 1; 2; 3; 4; 5. CodY homologs are present in most other low G+C Gram-positive bacteria and have been shown to play a global role in metabolic regulation and in coordinating expression of virulence-associated and metabolic genes 6; 7(see also 8; 9 and references therein).

B. subtilis CodY is a dimeric protein that uses a winged helix-turn-helix motif to bind to DNA 10; 11; 12. CodY binding requires the presence of a 15-bp motif, AATTTTCWGAAAATT 13; 14; 15. The DNA-binding activity of CodY is increased by interaction with two types of effectors, branched-chain amino acids [isoleucine, leucine, and valine (ILV)] 16; 17; 18; 19 and GTP 2; 18; 20; 21.

CodY achieves its maximal activity in media enriched with amino acids when the pools of its effectors are high 18; 22; 23; 24; 25; 26; 27. Under these conditions the synthesis of ILV becomes superfluous, and therefore it makes physiological sense that all genes involved in ILV biosynthesis are under negative CodY control 2; 28; 29; 30(http://www.genome.jp/kegg/expression/). The ybgE gene encodes one of the two branched-chain amino acid aminotransferases of B. subtilis 31; 32. ybgE is highly repressed by CodY as detected by DNA-microarray analysis, lacZ fusions, and other approaches 2; 28; 33. Because of the ybgE involvement in the ILV synthesis and because ybgE is one of the most highly CodY-regulated genes, we have been interested in the mechanism of its regulation.

The exact molecular mechanism of CodY-dependent repression or activation of transcription remains unknown. In most known cases, CodY-binding sites lie in the vicinity of the promoters of the target genes 15, and CodY likely acts by affecting important steps in transcription initiation.

In the present work, we demonstrate by genetic and biochemical approaches that the ybgE regulatory region has two CodY-binding sites that both contribute to repression, the downstream site being the more important of the two. Binding of CodY to the upstream site appears to inhibit transcription initiation. However, CodY binding to the ybgE downstream site, as well as to downstream sites of the bcaP and yufN genes, contributes to regulation by preventing elongation of transcription via a roadblock mechanism.

RESULTS

CodY-dependent regulation of the ybgE gene

We constructed a transcriptional fusion (ybgE292-lacZ) containing a 292-bp fragment that includes the entire intergenic region upstream of the coding sequence (Fig. 1); expression of the fusion was highly repressed by CodY (Table 1). Under conditions of maximal CodY activity, in a glucose-ammonium minimal medium containing ILV and a mixture of 13 other amino acids (referred to here as the 16 amino acid-containing medium), fusion activity in a codY null mutant strain (BB2771) was 380-fold higher than in the wild-type strain (BB2770). In the wild-type strain, activity of the fusion was derepressed about 10-fold in 13 amino acid-containing medium, i.e., when ILV were omitted, and was further increased 1.6-fold in the absence of all amino acids. Addition of ILV alone to glucose-ammonium medium reduced expression from the ybgE promoter about 5.5-fold (Table 1). This pattern of expression is common for CodY-repressed genes 15; 18; 22; 23; 34. However, regulation of ybgE is unusual in that: i) the gene is highly repressed by CodY (22-fold) even in glucose-ammonium medium in the absence of any exogenous amino acids, a condition in which CodY activity is very low; and, ii) expression is only moderately affected by addition of the 13 amino acid mixture alone. This amino acid-independent repression was previously detected in microarray experiments (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/expression/) and by Northern blot analysis 28. In a codY null mutant strain, there was only a 1.6-fold effect of the medium composition on ybgE expression, indicating that CodY itself or a CodY-dependent factor is the major regulator of ybgE under the conditions tested (Table 1, strain BB2771).

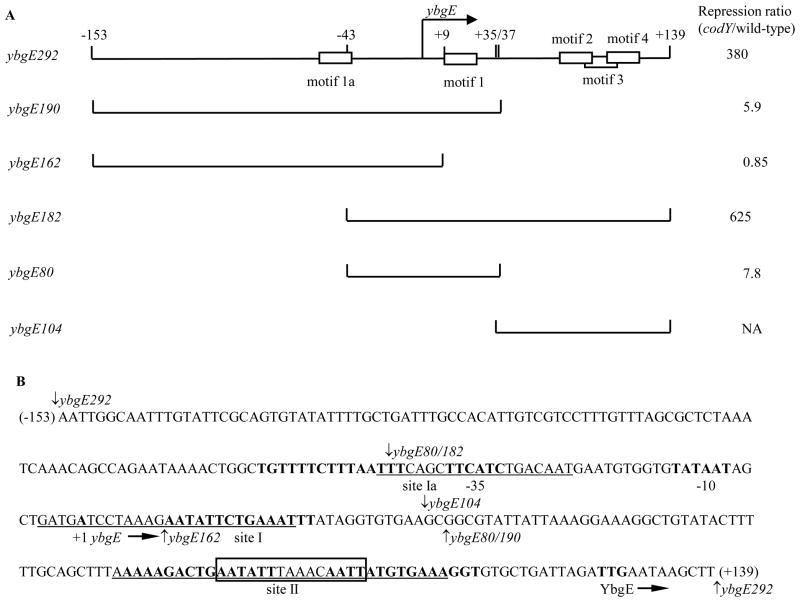

Fig. 1. Plasmid maps and the sequence of the ybgE regulatory region.

A. Schematic maps of the ybgE fragments used in this work. The location of the transcription start point is indicated by the bent arrow. CodY-binding motifs are shown as rectangles. The coordinates indicate the boundaries of different fragments with respect to the transcription start point. The repression ratio is the ratio of expression values for the corresponding lacZ fusions in codY null mutant and wild-type strains in the 16 amino acid-containing medium.

NA – not applicable. The ybgE104 fragment does not contain the promoter and therefore was not tested as part of a fusion.

B. The sequence of the coding (non-template) strand of the ybgE regulatory region. The likely initiation codon, −10 and −35 promoter regions, transcription start site and CodY-binding motifs (15-bp sequences similar to the proposed CodY-binding consensus) 1a, 1, 2, and 4 are in bold. CodY-binding motifs 3 is boxed. The direction of transcription and translation is indicated by the arrows. The sequences protected by CodY (sites Ia, I, and II) in DNase I footprinting experiments on the template strand of DNA are underlined. The boundaries of DNA fragments used in this work are indicated by vertical arrows. The coordinates of the 5′ and 3′ end of the sequence with respect to the transcription start point are shown in parenthesis.

Table 1.

Expression of ybgE-lacZ fusionsa

| Strain | Relevant genotype b | Fusion genotype | Additions β to the medium | -galactosidase activity (MU) | β-galactosidase activity (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB2770 | wild-type | ybgE292p+ (sites Ia, I, II) | none | 19.2 | 4.5 |

| ILV | 3.49 | 0.8 | |||

| 13 aa | 11.7 | 2.7 | |||

| 16 aa | 1.12 | 0.3 | |||

| BB2771 | codY | none | 268.0 | ||

| 16 aa | 428.0 | 100 | |||

| BB3301 | wild-type | ybgE292p1down | none | 42.3 | 6.2 |

| ILV | 14.8 | 2.2 | |||

| 13 aa | 38.9 | 5.7 | |||

| 16 aa | 13.5 | 2.0 | |||

| BB3302 | codY | none | 420.0 | ||

| 16 aa | 681.0 | 100 | |||

| BB3400 | wild-type | ybgE292p1down/11up | none | 10.2 | 1.5 |

| 16 aa | 2.52 | 0.4 | |||

| BB3415 | codY | none | 326.0 | ||

| 16 aa | 648.0 | 100 | |||

| BB2808 | wild-type | ybgE190p+ (sites Ia, I) | none | 78.0 | 80 |

| ILV | 48.2 | 49 | |||

| 13 aa | 51.3 | 52 | |||

| 16 aa | 16.5 | 17 | |||

| BB2818 | codY | none | 86.2 | ||

| 16 aa | 97.8 | 100 | |||

| BB3277 | wild-type | ybgE190p1up | 16 aa | 101.0 | 93 |

| BB3278 | codY | 16 aa | 109.0 | 100 | |

| BB2806 | wild-type | ybgE182p+ (sites I, II) | none | 1.90 | 2.2 |

| ILV | 0.31 | 0.4 | |||

| 13 aa | 1.24 | 1.4 | |||

| 16 aa | 0.14 | 0.2 | |||

| BB2816 | codY | none | 50.1 | ||

| 16 aa | 87.5 | 100 | |||

| BB2807 | wild-type | ybgE80p+ (site I) | none | 12.7 | 68 |

| ILV | 7.59 | 41 | |||

| 13 aa | 8.85 | 47 | |||

| 16 aa | 2.40 | 13 | |||

| BB2817 | codY | none | 14.6 | ||

| 16 aa | 18.7 | 100 | |||

| BB3026 | wild-type | ybgE162 (site Ia) | none | 204.0 | 121 |

| 16 aa | 199.0 | 118 | |||

| BB3028 | codY | none | 176.0 | ||

| 16 aa | 169.0 | 100 |

Cells were grown in TSS glucose-ammonium medium with or without a mixture of 16 amino acids (aa) or the same mixture without ILV (13 aa) or ILV only. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed and expressed in Miller units (MU). All values are averages of at least two experiments, and the mean errors did notexceed 30%.

Strain BB2511 and all its derivatives have very low endogenous β-galactosidase activity due to a null mutation in the lacA gene 56.

β-Galactosidase activity of each fusion in the 16 aa-containing medium in a strain containing a codY null mutation was normalized to 100%.

The transcription start point and CodY-binding sites

A primer extension experiment established that the 5′ end of the ybgE mRNA is located 127 bp upstream of the initiation codon (Fig. 2A). The sequences TTCATC and TATAAT, with three and no mismatches to the −35 and −10 regions of σA-dependent promoters, respectively, and a 17-bp spacer region, can be identified upstream of the location of the 5′ end, suggesting that this position corresponds to the transcription start point (Fig. 1B).

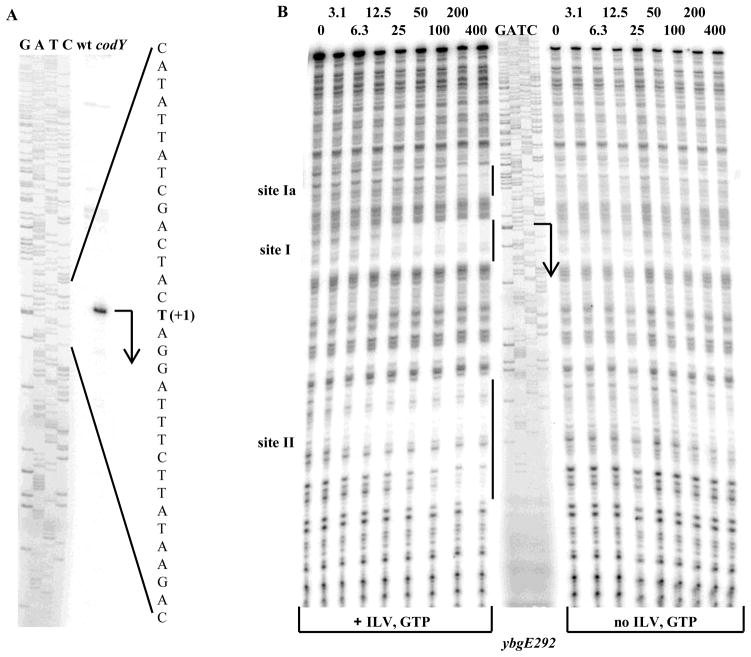

Fig. 2. Determination of the ybgE transcription start point and CodY-binding regions.

A. Primer extension analysis of the ybgE mRNA. Primer oBB102 annealing to the lacZ gene of the ybgE292-lacZ fusion containing the entire ybgE regulatory region was extended with reverse transcriptase using as the template total RNA from fusion-containing strains BB2770 (wt) and BB2771 (codY) grown in the 16 amino acid-containing medium. The sequence of the template strand of the ybgE fragment from pBB1506 determined from reactions primed with oBB102 is shown to the left. The apparent transcription start site of the ybgE gene is in bold and marked by the +1 notation. A bent arrow indicates the direction of transcription.

Additional faint bands observed in the primer extension lanes reflect unspecific binding of oBB102 to DNA and were present even when total RNA used for reverse transcription was isolated from a strain that did not contain the ybgE-lacZ fusion (data not shown).

B. DNase I footprinting analysis of CodY binding to the ybgE regulatory region. The ybgE292p+ DNA fragment labelled on the template strand was incubated with increasing amounts of purified CodY in the presence of 10 mM ILV and 2 mM GTP or in their absence and then with DNase I. The sequence of the ybgE region was determined by using pBB1506 as the template and oBB102 as the primer and is shown in the middle. The apparent transcription start site and direction of ybgE transcription are shown by the bent arrow. The protected areas are indicated by the vertical lines. CodY concentrations used (nM of monomer) are indicated above each lane.

Only one 15-bp sequence strongly resembling the CodY-binding consensus motif, AATTTTCWGAAAATT, and located between positions +10 and +24 with respect to the transcription start point, can be detected in the ybgE regulatory region 15. However, a DNase I footprinting experiment showed that in the presence of the effectors ILV and GTP, CodY protected three sites, Ia, I, and II, of the template DNA strand corresponding to positions −44 to −25, −4 to +22, and +80 to +112 with respect to the transcription start point, respectively (Fig. 1B and 2B). Binding to the upstream site Ia was seen only at high CodY concentrations, but binding to the other two sites occurred with high affinity (see also below). As expected, binding to all three sites was strongly dependent on the presence of CodY effectors (Fig. 2B).

Site I of the ybgE gene overlaps the previously recognized motif 1, that has only 2 mismatches with respect to the CodY-binding consensus motif (Fig. 1B and Table 2)(we use the terms “site” and “motif” to describe an experimentally determined location of CodY binding and a 15-bp sequence that is similar to the CodY-binding consensus, respectively). Site II overlaps with three interdigitated versions of the 15-bp sequence, motifs 2, 3, and 4, which have 4 to 5 mismatches each with respect to the CodY-binding consensus motif. The upstream CodY-binding site Ia partly overlaps a sequence, motif 1a, with 5 mismatches with respect to the CodY-binding consensus (Fig. 1B and Table 2).

Table 2.

CodY-binding motifs of the ybgE gene

| Motif | Sequencea | Number of mismatches | Scoreb | Location with respect to the transcription start point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus | AATTTTCWGAAAATT | 0 | 13.8–14.1 | |

| ybgE 1a | tgTTTTCTttAAtTT | 5 | 3.7 | −56 to −42 |

| ybgE 1 | AATaTTCTGAAAtTT | 2 | 10.3 | +10 to +24 |

| ybgE 2c | AAaagaCTGAAtATT | 5 | 6.5 | +81 to +95 |

| ybgE 3 | AATaTTtAaAcAATT | 4 | 6.8 | +90 to +104 |

| ybgE 4c | AATTaTgTGAAAggT | 4 | 4.1 | +101 to +115 |

| ybgE 1 p1 | AATaTTCTGgAAtTT | 3 | 6.5 | +10 to +24 |

| ybgE 3 p11 | AATTTTCAGAAAATT | 0 | 14.1 | +90 to +104 |

Mismatches to the proposed CodY-binding consensus are indicated by lower case letters. Mutations are in bold face.

The scores for individual CodY-binding motifs have been generated using the position-specific weight matrix as described in 15.

Parts of motifs 2 and 4 that overlap with motif 3 are underlined.

Roles of different CodY-binding sites

To find out to what extent the three CodY-binding sites detected in vitro contribute to regulation of ybgE, we created additional lacZ fusions containing truncated versions of the ybgE regulatory region lacking part of CodY-binding site Ia (ybgE182-lacZ) or site II (ybgE190-lacZ) or both (ybgE80-lacZ) (Fig. 1). (A point mutation in site I will be discussed later). The ybgE190-lacZ fusion deprived of the downstream CodY-binding site II was still repressed 6-fold by CodY in the 16 amino acid-containing medium (strains BB2808 and BB2818)(Table 1). The ybgE182-lacZ and ybgE80-lacZ fusions lacking part of the upstream CodY-binding site Ia (and most of the overlapping motif 1a) were regulated at levels similar to those of their respective counterparts ybgE292-lacZ and ybgE190-lacZ that carry the full upstream site (Table 1, compare strains BB2806, BB2770, BB2807, BB2808 and their codY derivatives). Thus, site Ia does not appear to contribute to regulation. On the other hand, site I does play a role, but, by itself, is responsible for only a fraction (6-fold) of total repression of ybgE. Hence, the downstream site II is required for maximal repression and is likely to be the main site of CodY-mediated repression. To prove some of these points, we constructed a fusion (ybgE162-lacZ) that retained site Ia but lacked site II and most of site I (Fig. 1). This fusion was not regulated by CodY (strains BB3026 and BB3028)(Table 1).

The maximal expression of the ybgE182-lacZ and ybgE80-lacZ fusions was reduced 5-fold compared to that of their respective counterparts ybgE292-lacZ and ybgE190-lacZ that carry additional upstream sequences (from positions −153 to −43) (Fig. 1, Table 1, strain BB2816 versus BB2771 and strain BB2817 versus BB2818). Part of the deleted sequence may serve as an UP element for the ybgE promoter 35; 36.

Affinities of CodY for sites I and II were very similar whether these sites were present on the same fragment of DNA or on separate fragments (Fig. 3A). Thus, binding of CodY to these two sites occurs independently. The weak binding to site Ia was much reduced by the deletion of motif 1a and had no effect on CodY binding to the nearby site I, consistent with our expression data in vivo (Fig. 3B).

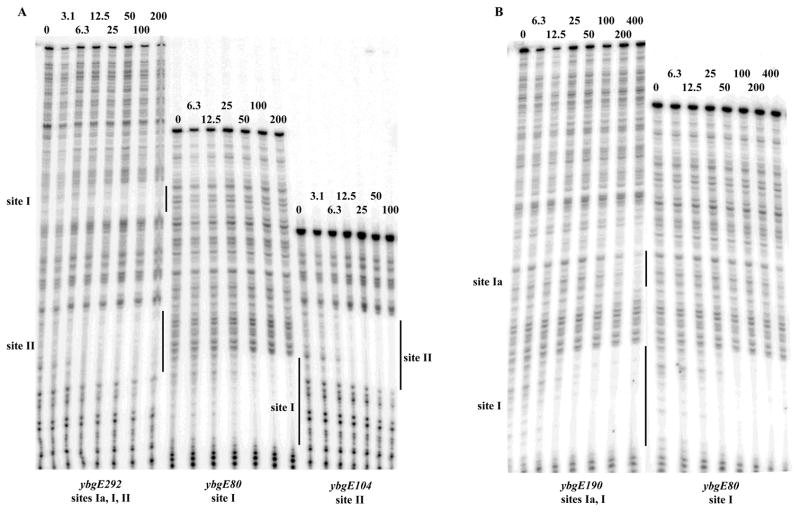

Fig. 3. Independent binding of CodY to the ybgE sites I and II.

Various labelled ybgE PCR fragments were analyzed by DNase I footprinting in the presence of 10 mM ILV and 2 mM GTP as described for Fig. 2B.

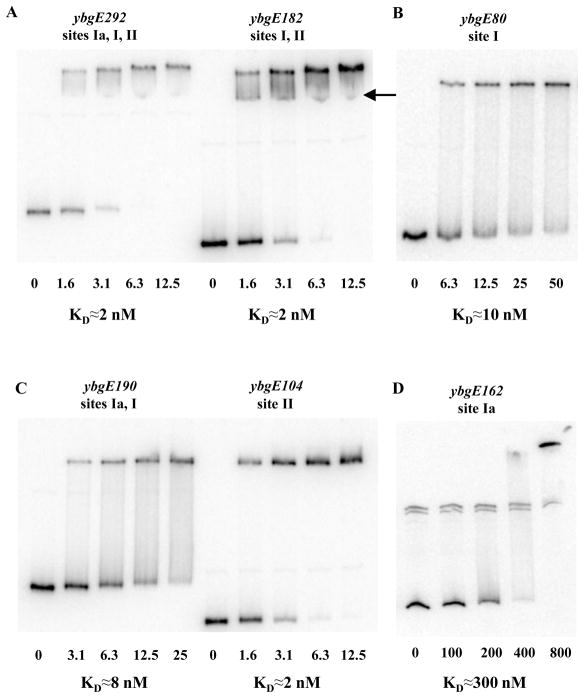

In gel-shift experiments, CodY bound to DNA fragments containing only site I (with or without complete site Ia) or only site II with apparent dissociation constants (KD) of ≈8–10 nM or ≈2 nM, respectively, compared with ≈2 nM for the full-length fragment (Fig. 4). Binding to site Ia was observed only at very high concentrations of CodY (200 to 400 nM) (Fig. 4D). The main complex between the full-length ybgE DNA fragment and CodY likely contains CodY molecules bound to both sites I and II. However, a second faint DNA-CodY complex apparently reflecting binding of CodY to only one of the sites could be detected (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Gel-shift assay of CodY affinity for ybgE DNA fragments.

Various labelled ybgE DNA fragments were incubated with increasing amounts of purified CodY in the presence of 10 mM ILV and 2 mM GTP. CodY concentrations used (nM of monomer) are indicated below each lane. The arrow indicates a likely complex in which CodY is bound only to one binding site as opposed to two sites simultaneously. KD, the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant, reflects the CodY concentration needed to shift 50% of DNA fragments under conditions ofvast CodY excess over DNA.

Mutations in ybgE sites I and II

To confirm the role of site I in ybgE regulation and to quantify directly the contribution of site II, we changed the very highly conserved A10 residue of CodY-binding motif 1 to G (the p1 down mutation) (Table 2) and compared the resulting phenotype in the presence or absence of site II. Whereas the ybgE190p+-lacZ fusion, lacking site II, was still repressed 6-fold by CodY, the ybgE190p1-lacZ fusion lost all ability to be repressed, indicating that the p1 mutation completely inactivated site I as a target of CodY-dependent regulation (Table 1, strains BB2808 and BB3277 and their codY derivatives). However, the ybgE292p1-lacZ fusion, containing the mutated site I and wild-type site II, was still repressed 50-fold by CodY, consistent with our suggestion that site II is responsible for the major part of CodY-dependent regulation and that site I is required for maximal repression (Table 1, strains BB3301 and BB3302). Since site I alone accounts for ~6-fold repression, site II alone provides ~50-fold repression, and the two sites together give ~380-fold repression, sites I and II act independently in an additive manner.

To analyze further the role of site II in interaction with CodY, we introduced four substitutions (collectively, the p11 up mutation) within motif 3 (the motif that is completely contained within site II) to create a perfect match to the consensus (Table 2). (Alteration of motif 3 by the p11 mutation introduced an additional mismatch in the overlapping motif 2 but did not affect the sequence of the overlapping motif 4.) When the p11 mutation was present simultaneously with the down mutation p1 in site I, expression of the ybgE292p1/11-lacZ fusion was reduced 5-fold in the 16 amino acid-containing medium compared to the fusion carrying the p1 mutation only, indicating that the native site II is not fully occupied by CodY under these conditions (Table 1, strains BB3301 and BB3400) (we have not tested the effect of the p11 mutation alone).

CodY represses ybgE transcription in vitro

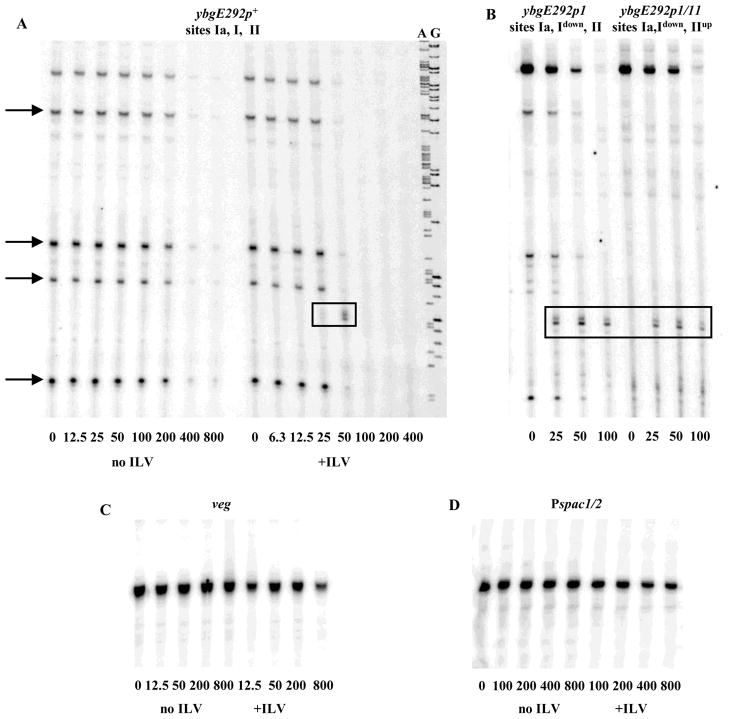

CodY efficiently repressed transcription from the ybgE promoter in vitro and did so in an ILV-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). In addition to the run-off transcript of 177 nucleotides, shorter transcription products of about 60, 84, 94, and 153 nucleotides were observed in most experiments when the ybgE regulatory region was used as a template, indicating the presence of several strong RNA polymerase pause sites in the region (Fig. 5A and B). CodY repressed the ybgE promoter much more strongly than the B. subtilis veg promoter or the semi-synthetic Pspac1/2 promoter 37, which we used as controls since they are not regulated by CodY and do not bind CodY in vitro (Fig. 5C and D).

Fig. 5. Repression of ybgE expression in vitro.

A. The 441-bp ybgE292p+ PCR fragment was transcribed in vitro using purified B. subtilis RNA polymerase in the presence of increasing amounts of CodY with or without 10 mM ILV. GTP concentration was 0.2 mM in all samples. The A and G sequencing reactions used for sizing the transcripts are shown to the right. CodY concentrations used (nM of monomer) are indicated below each lane. Strong RNA polymerase pause sites are indicated with arrows. The roadblock transcription products are boxed.

B. The same as Fig. 5A using the ybgE292p1 and ybgE292p1/11 PCR fragments and 10 mM ILV. A down or up notation indicates the presence of a down or up mutation in the CodY-binding site.

C. The same as Fig. 5A using the 376-bp PCR fragment containing the veg promoter.

D. The same as Fig. 5A using the 494-bp PCR fragment containing the Pspac1/2 promoter.

CodY as a transcriptional roadblock

In addition to greatly reducing overall transcription from the ybgE promoter in vitro, the presence of CodY led to the appearance of two novel transcription products that were shorter than the full-length run-off transcript but did not correspond to any of the paused transcripts seen in the absence of CodY. This doublet transcript was the size expected for RNA molecules that terminate at the location of the downstream CodY-binding site II (Fig. 5A and B, Table 3). The presence of CodY did not cause the appearance of any additional transcripts from the veg or Pspac1/2 promoters (data not shown). Inactivation of the ybgE promoter by the ybgEp2 mutation that changed the −10 region sequence from TATAAT to CATAAT prevented the formation of all transcripts, including the transcript that appeared only in the presence of CodY (data not shown). Thus, the novel transcript originated from the ybgE promoter and resulted from a pause/stop site that functions only in the presence of CodY.

Table 3.

Sizes of in vitro transcriptsa

| Gene | Size of a full-length transcript expected observed | Distance from the transcription start point to the downstream CodY-binding motif | Size of the shortest terminated transcript | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ybgE | 175 | 177 | 80b | 76 |

| bcaP | 131 | 133 | 70 | 67 |

| yufN | 308c | 309 | 168 | 164 |

| gudBp2 | 235 | 233 | 124 | 120 |

DNA sequencing ladders were used to determine transcript sizes (in nucleotides). The deduced transcript size was calculated using the coefficient of 0.96, reflecting the average difference in mass between dNTPs and NTPs.

The distance to the proximal motif 2 of site II is specified.

The apparent yufN transcription start point was determined to be 270 bp upstream of the initiation codon (Belitsky and Sonenshein, manuscript in preparation).

The prematurely terminated products could be detected only in a narrow range of CodY concentrations at which total ybgE transcription was much reduced. We hypothesized that the appearance of the premature termination product would be more easily detectable if we reduced the repressive effect of CodY at the level of transcription initiation, e.g., by inactivating the CodY-binding site I that overlaps the transcription start point. Indeed, the premature termination products appeared at a lower CodY concentration when a site I mutant template (ybgEp1) was used and did not disappear as fast as the CodY concentration was raised (Fig. 5B). Increasing the strength of CodY binding to site II by introducing the p11 mutation did not noticeably affect the efficiency of premature termination (Fig. 5B).

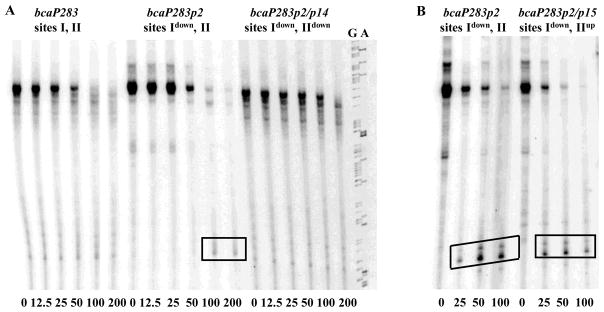

Our previous analysis of the B. subtilis genome showed that two other CodY-regulated genes, bcaP (yhdG) and yufN may possess two CodY-binding sites located widely apart in the corresponding regulatory regions 15. In fact, we recently showed that, similar to the situation for ybgE, the two CodY-binding sites of the B. subtilis bcaP regulatory region both contribute independently to repression 34. In that work, we hypothesized that binding of CodY to site I of the bcaP gene serves to inhibit initiation of transcription, and binding of CodY to site II, located 70 bp downstream of the transcription start point may cause premature termination of transcription. In fact, in the presence of CodY two novel bcaP transcription products were observed that corresponded in size to the expected product of premature termination of transcription at the downstream CodY-binding site II (Fig. 6, Table 3). These products were barely detectable unless the upstream CodY-binding site I was inactivated by the p2 mutation, disappeared if the downstream site II was made weaker by the p14 mutation, and were not affected by the p15 mutation that makes site II stronger 34 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. CodY acts as roadblock for transcription from the bcaP promoter in vitro.

428-bp PCR fragments containing various versions of the bcaP promoter were transcribed in vitro as described in Fig. 5B. The G and A sequencing reactions used for sizing the transcripts are shown to the right. Panels A and B show results from two independent experiments.

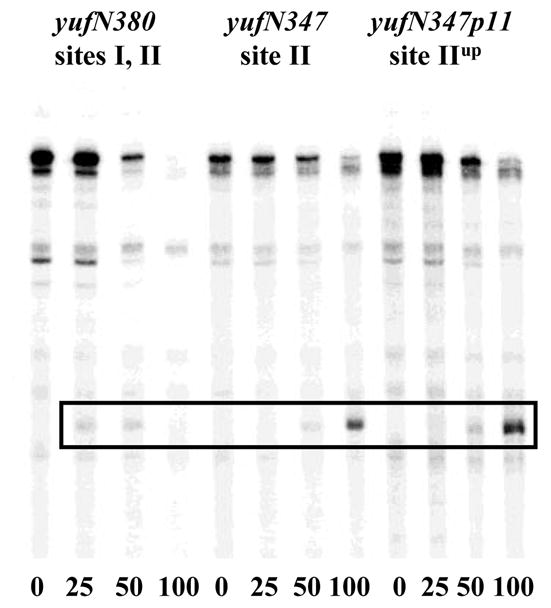

In addition, a novel shortened transcription product was observed in the presence of CodY when the yufN promoter was transcribed in vitro (Fig. 7). The size of this transcript corresponded well to the size expected for a transcript that terminates at the location of the yufN downstream CodY-binding site II (Table 3). As in case of bcaP, this product was reproducibly detected only if the yufN upstream CodY-binding site I was inactive. Unlike the case for ybgE and braP, increasing the strength of the yufN downstream CodY-binding site II by the p11 mutation increased the efficiency of premature termination (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. CodY acts as a roadblock for transcription from the yufN promoter in vitro.

645-bp (yufN503) or 489-bp (yufN347) PCR fragments, containing various versions of the yufN promoter, were transcribed in vitro as described in Fig. 5B. Analysis of the CodY-binding sites of the yufN gene will be presented separately (Belitsky and Sonenshein, manuscript in preparation).

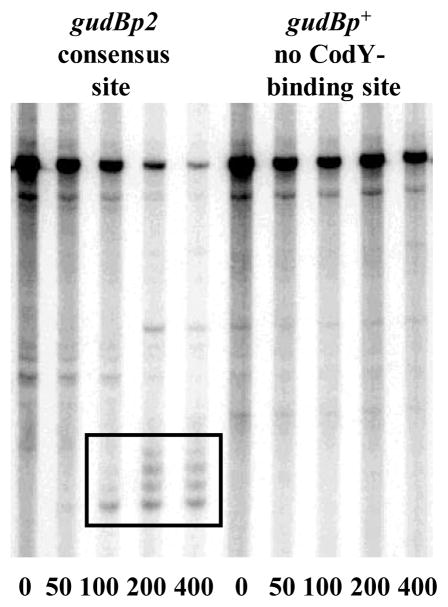

Finally, we introduced 6 closely spaced substitution mutations in the sequence of the B. subtilis gudB gene 38 to create a perfect 15-bp CodY-binding motif starting 124 bp downstream of the transcription start point (the gudBp2 allele). The gudBp2 DNA fragment bound CodY with high affinity (≈3 nM), ≥150-fold stronger than the gudBp+ fragment (data not shown). The presence of increasing CodY concentrations in the in vitro transcription system led to the formation of several truncated transcripts only when the modified gudB template was used. The sizes of these transcripts (from 125 to 136 nucleotides) corresponded to the expected sizes of transcripts blocked due to CodY binding (Fig. 8, Table 3).

Fig. 8. CodY binding creates a roadblock for transcription from the gudB promoter in vitro.

597-bp PCR fragments, containing the p+ and p2 versions of the gudB promoter, were transcribed in vitro as described in Fig. 5B.

Role of Mfd in CodY-mediated repression at downstream binding sites

Transcription-repair coupling factor Mfd 39 promotes dissociation of RNA polymerase stalled at DNA lesions of various nature or at protein roadblocks 40; 41; 42; 43. Mfd enhances the efficiency of roadblocks formed in vivo by binding of B. subtilis CcpA or Escherichia coli LacI to sites downstream of the promoter 42; 44. Apparently, RNA polymerase molecules impeded by proteins bound to DNA can occasionally resume elongation, given enough time, due to the dynamic nature of interactions between the proteins and their binding sites. However, Mfd, if present, promotes dissociation of RNA polymerase, eliminating their chance to overcome the impediment. Inactivation of Mfd caused several-fold higher expression of the ybgE-, bcaP-, and yufN-lacZ fusions that contained downstream sites II as the only or principal region able to interact with CodY (Table 4). The positive effect of the mfd null mutation on expression of the fusions required the presence of CodY and was much reduced in codY null mutants. The remaining ≤2-fold positive effect of mfd null mutation (Table 4) was detected previously for other lacZ fusions 44. Mfd did not significantly affect the regulation of the ybgE-, bcaP-, and yufN-lacZ fusions that contained upstream sites I as the only region able to interact with CodY (Table 4). The observed role of Mfd in CodY-dependent regulation at the downstream sites confirms that CodY molecules bound to these sites prevent progression of RNA polymerase.

Table 4.

Effect of Mfd on CodY-mediated repression at the downstream sitesa

| Strain | Relevant genotypeb | Fusion genotypec | β-galactosidase activity (MU) | Relief of repression in the mfd mutant (fold)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB2808 | wild-type | ybgE190p+ (site I) | 16.5 | |

| BB2818 | codY | 97.8 | ||

| BB3554 | mfd | 18.7 | 1.1 | |

| BB3301 | wild-type | ybgE292p1 (site Idown, II) | 13.5 | |

| BB3302 | codY | 681.0 | ||

| BB3555 | mfd | 35.6 | 2.6 | |

| BB3573 | mfd codY | 783.0 | 1.1 | |

| BB3400 | wild-type | ybgE292p1/11 (site Idown, IIup) | 2.52 | |

| BB3415 | codY | 648.0 | ||

| BB3556 | mfd | 51.9 | 21.0 | |

| BB3574 | mfd codY | 861.0 | 1.3 | |

| BB2764 | wild-type | bcaP235p+ (site I) | 6.49 | |

| BB2767 | codY | 345.0 | ||

| BB3551 | mfd | 3.59 | 0.6 | |

| BB2822 | wild-type | bcaP167p+ (site II) | 0.10 | |

| BB2844 | codY | 5.82 | ||

| BB3552 | mfd | 2.24 | 22.0 | |

| BB3571 | mfd codY | 10.6 | 1.8 | |

| BB3399 | wild-type | bcaP167p15 (site IIup) | ≤0.03 | |

| BB3414 | codY | 4.42 | ||

| BB3553 | mfd | 0.12 | ≥6.0 | |

| BB3572 | mfd codY | 9.18 | 2.1 | |

| BB2809 | wild-type | yufN276p+ (site I) | 0.09 | |

| BB2819 | codY | 6.04 | ||

| BB3557 | mfd | 0.17 | 1.9 | |

| BB2899 | wild-type | yufN347p+ (site II) | 1.61 | |

| BB2906 | codY | 10.4 | ||

| BB3558 | mfd | 10.0 | 6.2 | |

| BB3575 | mfd codY | 22.5 | 2.2 | |

| BB3401 | wild-type | yufN347p11 (site IIup) | 0.04 | |

| BB3416 | codY | 2.01 | ||

| BB3559 | mfd | 0.46 | 12.0 | |

| BB3576 | mfd codY | 3.75 | 1.9 |

Cells were grown in TSS glucose-ammonium medium with a mixture of 16 amino acids. β-Galactosidase activity was as described in Table 1.

Strain BB2511 and all its derivatives have very low endogenous β-galactosidase activity due to a null mutation in the lacA gene 56.

Construction of the yufN fusions will be described separately (Belitsky and Sonenshein, manuscript in preparation). A down or up notation indicates the presence of a down or up mutation in the CodY-binding site.

The ratios of expression levels between mfd and wild-type strains or between mfd codY and codY strains are shown.

DISCUSSION

CodY-binding sites of the ybgE gene

We have identified two high affinity CodY-binding sites within the ybgE regulatory region. Both sites contribute to repression but do so independently. Site I of the ybgE gene is associated with a CodY-binding motif of relatively high similarity (2 mismatches) to the consensus motif, AATTTTCWGAAAATT. In contrast, site II contains three overlapping CodY-binding motifs all of which have poor similarity to the consensus. This overlapping arrangement of CodY-binding motifs resembles the sequence of the CodY-binding site of the dpp operon 10; 15 and likely causes higher affinity for CodY. In neither of these two cases, however, has the contribution of individual motifs to CodY binding or regulation been analyzed.

Multiple mechanisms of CodY-mediated regulation

CodY regulates directly several dozen transcriptional units 2. In the case of positively regulated genes, CodY binds upstream of the −35 promoter region 45(our unpublished data). In most cases of negatively regulated genes, CodY-binding sites overlap the promoter or are located immediately upstream of the −35 region 15. The CodY-binding site I of the ybgE gene overlaps the transcription start point, and therefore CodY binding to this site most likely inhibits transcription by interfering with RNA polymerase binding.

The CodY-binding site II of the ybgE gene begins 80 bp downstream of the transcription start point and extends a further 32 bp. Our in vitro experiments showed that CodY binding to site II of ybgE inhibits RNA polymerase elongation, i.e., represses transcription by a roadblock mechanism. Our previous work identified two independently active CodY-binding sites for the B. subtilis bcaP gene, one of which is located downstream of the promoter 34. The present work shows that CodY binding to the bcaP downstream site and a similar downstream site of the B. subtilis yufN gene also inhibits transcription by a roadblock mechanism. It is likely that other genes in B. subtilis and other bacteria are regulated in a similar way.

Thus, CodY is a versatile transcriptional regulator that can affect transcription in at least three different ways: activation (apparently through direct interaction with RNA polymerase), repression at the level of transcription initiation, and repression of RNA polymerase elongation by a roadblock mechanism. The ability of CodY to repress transcription in vivo through binding to downstream sites is enhanced by the transcription-repair coupling factor Mfd, which promotes dissociation of RNA polymerase molecules stalled at roadblocks positioned at ≥30–40 bp downstream of a transcription start point 46; 47. On the one hand, this observation reinforces our conclusion that CodY binding to downstream sites generates a roadblock for transcription. On the other hand, it shows that the role of Mfd in regulation of transcription elongation is likely more widespread than is reflected in the literature 41; 44; 46; 48.

Role of CodY-binding sites in ybgE regulation

From the expression analysis of the truncated and mutant fusions, it is apparent that site II of the ybgE gene is responsible for most of the repression in the absence of exogenous amino acids, i.e., under conditions when CodY activity is the lowest, and for the additional repression provided by the presence of ILV in glucose-ammonium medium (Table 1). Site I appears to contribute to ybgE repression only when cells are grown in 16 amino acid-containing medium, i.e., when CodY is most active. This is consistent with site II having higher affinity for CodY than does site I. The strong correlation between affinity and contribution to regulation for the two ybgE CodY-binding sites is in contrast to the situation for the bcaP gene, however. In the latter case, the higher affinity downstream site II contributes to repression no more than or even less than the lower affinity upstream site I 34. We can conclude that CodY-mediated repression by a roadblock mechanism is not intrinsically less efficient than repression at the level of transcription initiation. At the same time, the extent to which affinity, as measured in vitro, correlates with strength of regulation in vivo is still unclear. Whatever the mechanism of repression, the presence of two binding sites with different affinities for CodY permits a promoter to respond to a wider range of intracellular concentrations of effectors 34.

Low threshold for repression of ybgE expression

The ybgE gene is unusual among CodY-repressed genes because it is highly repressed in glucose-ammonium medium in the absence of exogenous ILV and amino acids. Most other genes negatively regulated by CodY are expressed in the absence of amino acids in the medium at a level of 30–100% of their maximal expression levels. Only one other gene, yurP, is repressed more than 10-fold under such growth conditions 15. Apparently, the ybgE regulatory region is able to interact with CodY very efficiently even when CodY is poorly active due to low pools of the effectors.

It is likely no coincidence that ybgE, encoding the enzyme catalyzing the last step of ILV biosynthesis, is apparently the gene that is most efficiently repressed gene by poorly active population of CodY molecules and that gets fully derepressed only when CodY is completely inactive. The lowest activity of CodY is apparently achieved only under conditions of ILV limitation. These are the growth conditions when the cell needs to maximize ILV biosynthesis in order to maintain growth. In case of ybgE, this is achieved by completely relieving the gene from CodY-mediated repression. Interestingly, a similar goal is achieved by an entirely different strategy by the ilvB operon that contains seven other genes involved in ILV biosynthesis. A transcription antitermination mechanism is called into play only during leucine limitation. If ILV supply is sufficient, the resulting termination allows only moderate expression of the ilvB operon 33; 49. Expression of both ybgE and ilvB is further reduced in the presence of exogenous ILV and other amino acids in the medium through the action of CodY 2. Thus, in case of the ilvB operon, two different regulatory mechanisms are responsible for the adjustment of its expression to conditions of ILV feast and famine. In case of ybgE, CodY plays both of these roles, rather unusually for a regulator whose main function is cell adaptation to growth in nutrient-replete conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture media

The B. subtilis strains created in this study were all derivatives of strain SMY 50 and are described in Table 5 and in the text. E. coli strain JM107 51 was used for isolation of plasmids. Cells growth was as described 34

TABLE 5.

B. subtilis strains used

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| SMY | wild-type | 50 |

| PS251 | codY::(erm::spc) trpC2 | P. Serror |

| SF22CDH-T | mfd22::Tn10(cat::tet) trpC2 | S. Fisher |

| BB2511 | ΔamyE::spc lacA::tet | 15 |

| BB2770 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE292p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 x pBB1506 |

| BB2806 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE182p+-lacZ] lacA::tet | BB2511 x pBB1517 |

| BB2807 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE80p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 x pBB1518 |

| BB2808 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE190p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 x pBB1519 |

| BB3026 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE162p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 x pBB1581 |

| BB3277 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE190p1-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 x pBB1638 |

| BB3301 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE292p1-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 x pBB1645 |

| BB3400 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE292p1/11-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 x pBB1675 |

| BB3531 | mfd22::Tn10(cat::tet) | SMY x DNA(SF22CDH-T) |

| BB3534 | mfd22::Tn10(cat::neo) | BB3531 x pCm::Nm 57 |

DNA manipulations

Methods for common DNA manipulations, transformation, primer extension, DNA sequencing, gel shift experiments, DNase I footprinting, and sequence analysis were as previously described 15; 34; 52. Chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis strain SMY or plasmids containing appropriate promoters were used as templates for PCR if not noted otherwise. All oligonucleotides used in this work are described in Table 6. All cloned PCR-generated fragments were verified by sequencing by the Tufts University Core Facility.

Table 6.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

| Name | Sequence | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Flanking forward primers | ||

| oRPS11b | 5′-GGGGGGATCCCCGGATCTGACGGTTAACAAGCTGGCGGGG | ybgE292 |

| oSP20b | 5′-CTGAGAATTGGTATGCC | veg |

| oBB67 | 5′-GCTTCTAAGTCTTATTTCC | erm (pHK23) |

| oBB211 | 5′-GAATTCTAGAATGCCCAGTCCAGACTATTC | Pspac1/2 (pBB1375) |

| oBB355 | 5′-TCTTTGAATTCAGCTTCATCTGAC | ybgE182 |

| oBB364 | 5′-GCGGCGTATTATTAAAGG | ybgE104 |

| Flanking reverse primers | ||

| oRPS12 | 5′-GGGGGAATTCGCGTAAGCGGTGCGTACGGCGC | ybgE292 |

| oSP21 | 5′-CAGAAGGGTACGTCTCAG | veg |

| oBB102 | 5′-CACCTTTTCCCTATATAAAAGC | lacZ (pHK23) |

| oBB253 | 5′-GGTTTTCCCGGTCGAC | lacZ (pHK23) |

| oBB295 | 5′-ACCGGGACGTCGGATCCTAGAAGCTTATC | pBB1375 (Pspac1/2) |

| oBB356 | 5′-ATACGAAGCTTCACACCTATAAATTTC | ybgE190 |

| oBB410 | 5′-AGAATAAGCTTTAGGATCATCAGC | ybgE162 |

| oBB465 | 5′-CTTTACTGAACCGTCG | gudB |

| oBB469 | 5′-ATACGAAGCTTCACACCTATAAATTgCAGa | ybgE190p1 |

| Internal mutagenic forward primer | ||

| oBB442 | 5′-AATTTTCTGAAAATTTTGGGATATCCCGAAGA | gudBp2 |

| oBB476 | 5′-ATTCTGcAATTTATAGGTGTGAAGa | ybgE292p1 |

| oBB500 | 5′-GAATTTTCAGAAAATTATGTGAAAGGTGa | ybgE292p11 |

| oBB544 | 5′-GTGGTGcATAATAGCTGATG | ybgE292p2 |

| Internal mutagenic reverse primer | ||

| oBB441 | 5′-CCCAAAATTTTCAGAAAATTATGTATTACGGTTTG | gudBp2 |

| oBB475 | 5′-CACCTATAAATTgCAGAATATTCa | ybgE292p1 |

| oBB499 | 5′-TTCACATAATTTTCTGAAAATTCAGTCa | ybgE292p11 |

| oBB543 | 5′-CATCAGCTATTATgCACCAC | ybgE292p2 |

The altered nucleotides are in bold; those conferring up mutations in the CodY-binding motif are in upper case, those conferring down mutations in the CodY-binding motif or in the promoter are in low case. The EcoRI and HindIII sites are underlined.

oRPS and oSP primers were designed by R. Shivers and S. Picossi, respectively.

Construction of transcriptional lacZ fusions

To create a full-length ybgE transcriptional fusion, the 0.54-kb PCR product was synthesized by using ybgE-specific oligonucleotides, oRPS11 and oRPS12, as the forward and reverse primers, respectively. The 0.29-kb fragment of this PCR product containing the entire intergenic region upstream of the ybgE gene was cut at the intrinsic MfeI and HindIII sites, and cloned between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of the integrative plasmid pHK23 15 to create pBB1506 (ybgE292p+-lacZ). pBB1517 (ybgE182p+-lacZ) carrying a 182-bp version of the ybgE regulatory region truncated by 110 bp at the 5′ end was created in a similar manner but using oligonucleotide oBB355 as the forward primer and cutting the 5′ end of the product at the EcoRI site that was incorporated into oBB355. pBB1519 (ybgE190p+-lacZ) and pBB1581 (ybgE162p+-lacZ) carrying 190-bp and 162-bp versions of the ybgE regulatory regions, respectively, truncated at the 3′-end were created in a manner similar to pBB1506 but with oligonucleotides oBB356 or oBB410 containing the HindIII site as the reverse primers, respectively. pBB1518 (ybgE80p+-lacZ) carrying a 80-bp version of the ybgE regulatory region truncated both at the 5′- and 3′-end was created in a manner similar to pBB1517 but with oligonucleotide oBB356 as the reverse primer.

B. subtilis strains carrying various lacZ fusions at the amyE locus (Table 5) were isolated after transforming strain BB2511 (amyE::spc) with the appropriate plasmids, by selecting for resistance to erythromycin conferred by the plasmids, and screening for loss of the spectinomycin-resistance marker, which indicated a double crossover, homologous recombination event.

Mutations in the promoter and CodY-binding sites

The p1 mutation in the ybgE190 regulatory region (pBB1638) was introduced by using the mutagenic primer oBB469 as a forward primer for PCR. The p1 mutation in the ybgE292 regulatory region was introduced by two-step overlapping PCR. In the first step, a product containing the 5′-part of the ybgE regulatory region was synthesized by using oligonucleotide oRPS11 as the forward primer and mutagenic oligonucleotide oBB475 as the reverse primer. In a similar manner, a product containing the 3′-part of the ybgE regulatory region was synthesized by using mutagenic oligonucleotide oBB476 as the forward primer and oligonucleotide oRPS12 as the reverse primer. The two PCR products were used in a second, splicing step of PCR mutagenesis as overlapping templates to generate a modified fragment containing the entire ybgE regulatory region; oligonucleotides oRPS11 and oRPS12 served as the forward and reverse PCR primers, respectively. The spliced PCR product was digested with MfeI and HindIII and cloned in pHK23, to create pBB1645 (ybgE292p1-lacZ).

The p2 mutation in the ybgE292p1 regulatory region was introduced by two-step overlapping PCR as described above using mutagenic oligonucleotides oBB543 and oBB544, pBB1645 (ybgE292p1-lacZ) as template and oBB67 and oBB102 as flanking primers.

The p11 mutation in the ybgE292p1 regulatory region (pBB1675) was introduced by two-step overlapping PCR as described above using mutagenic oligonucleotides oBB499 and oBB500, pBB1645 (ybgE292p1-lacZ) as template and oBB67 and oBB253 as flanking primers.

The ybgE104 PCR fragment lacking CodY-binding site I was synthesized using oBB364 and oBB102 as primers.

The p2 mutation in the gudB gene was introduced by two-step overlapping PCR as described above using mutagenic oligonucleotides oBB441 and oBB442, pBB933 (gudBp+-lacZ) 38 as template and oBB67 and oBB102 as flanking primers. The spliced PCR product was cut at the HindIII and EcoRI sites, originating from the vector, and cloned in pJPM82 53, to create pBB1620 (gudBp2-lacZ).

Labeling of DNA fragments

The PCR products containing the regulatory region of the ybgE gene were synthesized using vector-specific oligonucleotide oBB67 as the forward primer and lacZ-specific oligonucleotide oBB102 as the reverse primer (Table 6). The reverse primer for each PCR reaction (which would prime synthesis of the template strand of the PCR product) was labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]-ATP. oBB67 starts 112 bp upstream of the EcoRI site used for cloning, and oBB102 starts 36 downstream of the HindIII site that serves as a junction between the regulatory regions and the lacZ part of the fusions.

In vitro transcription

Reactions were performed in a 10 μl total volume that contained 40 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)-10 mM MgCl2-5% glycerol-0.1 mM EDTA-1 mM dithiothreitol-0.1 mg/ml BSA, 2 un RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), 200 μM ATP, CTP, and GTP, 10 μM UTP, 0.5 to 1 μCi α-32P-UTP, a mixture of B. subtilis RNA polymerase holoenzyme and σA factor preincubated for 30 min at 4°C (final concentrations 0.02 μM and 0.4 μM, respectively), and various amounts of CodY. 10 mM ILV was added to the reactions if not specified otherwise. His-tagged RNAP and σA factor were purified from B. subtilis cells asdescribed 54; 55.

Different PCR-generated fragments containing the regulatory regions were used as templates (~50 nM). The ybgE, bcaP, and yufN fragments for in vitro transcription were created using plasmids containing corresponding lacZ fusions as templates and oligonucleotides oBB67 and oBB102 that flank the promoter inserts. The veg and Pspac1/2 promoters were amplified using oligonucleotides specific to their sequences and chromosomal DNA of strain SMY or pBB1375 37 as template, respectively. The gudB PCR fragments were obtained using oligonucleotides oBB67 and oBB465 and pBB933 38 or pBB1620 as templates.

The reactions were preincubated at 37° C for 15 min, initiated by addition of the nucleotide mixture, incubated for 20 min, and terminated by addition of 4 μl of the 20 mM EDTA-95% formamide dye solution and subsequent heating of the samples at 80°C for 5 min. The samples were analyzed without further purification using 5% polyacrylamide DNA sequencing gels containing 7 M urea; the radioactive bands were detected and quantified using storage screens, an Applied Biosystems Phosphor Imager, and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

Purification of CodY

Wild-type CodY was purified to near homogeneity as described previously 15.

Enzyme assays

β-Galactosidase specific activity was determined as described previously 38.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Picossi for purification of RNA polymerase and the σA factor and to S. Fisher for the gift of a mfd strain. This work was supported by a research grant (GM042219) from the U. S. Public Health Service.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Slack FJ, Serror P, Joyce E, Sonenshein AL. A gene required for nutritional repression of the Bacillus subtilis dipeptide permease operon. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:689–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molle V, Nakaura Y, Shivers RP, Yamaguchi H, Losick R, Fujita Y, Sonenshein AL. Additional targets of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY identified by chromatin immunoprecipitation and genome-wide transcript analysis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1911–1922. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1911-1922.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonenshein AL. CodY, a global regulator of stationary phase and virulence in Gram-positive bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonenshein AL. Control of key metabolic intersections in Bacillus subtilis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:917–927. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher SH. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: vive la difference! Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:223–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luong TT, Sau K, Roux C, Sau S, Dunman PM, Lee CY. Staphylococcus aureus ClpC divergently regulates capsule via sae and codY in strain Newman but activates capsule via codY in strain UAMS-1 and in strain Newman with repaired saeS. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:686–694. doi: 10.1128/JB.00987-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caymaris S, Bootsma HJ, Martin B, Hermans PW, Prudhomme M, Claverys JP. The global nutritional regulator CodY is an essential protein in the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:344–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dineen SS, McBride SM, Sonenshein AL. Integration of metabolism and virulence by Clostridium difficile CodY. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5350–5362. doi: 10.1128/JB.00341-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majerczyk CD, Dunman PM, Luong TT, Lee CY, Sadykov MR, Somerville GA, Bodi K, Sonenshein AL. Direct targets of CodY in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2861–2877. doi: 10.1128/JB.00220-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serror P, Sonenshein AL. Interaction of CodY, a novel Bacillus subtilis DNA-binding protein, with the dpp promoter region. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:843–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levdikov VM, Blagova E, Joseph P, Sonenshein AL, Wilkinson AJ. The structure of CodY, a GTP- and isoleucine-responsive regulator of stationary phase and virulence in gram-positive bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11366–11373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph P, Ratnayake-Lecamwasam M, Sonenshein AL. A region of Bacillus subtilis CodY protein required for interaction with DNA. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4127–4139. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.4127-4139.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guedon E, Sperandio B, Pons N, Ehrlich SD, Renault P. Overall control of nitrogen metabolism in Lactococcus lactis by CodY, and possible models for CodY regulation in Firmicutes. Microbiology. 2005;151:3895–3909. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.den Hengst CD, van Hijum SA, Geurts JM, Nauta A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. The Lactococcus lactis CodY regulon: identification of a conserved cis-regulatory element. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34332–34342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. Genetic and biochemical analysis of CodY-binding sites in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1224–1236. doi: 10.1128/JB.01780-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guedon E, Serror P, Ehrlich SD, Renault P, Delorme C. Pleiotropic transcriptional repressor CodY senses the intracellular pool of branched-chain amino acids in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1227–1239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petranovic D, Guedon E, Sperandio B, Delorme C, Ehrlich D, Renault P. Intracellular effectors regulating the activity of the Lactococcus lactis CodY pleiotropic transcription regulator. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:613–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shivers RP, Sonenshein AL. Activation of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY by direct interaction with branched-chain amino acids. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:599–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.den Hengst CD, Curley P, Larsen R, Buist G, Nauta A, van Sinderen D, Kuipers OP, Kok J. Probing direct interactions between CodY and the oppD promoter of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:512–521. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.512-521.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratnayake-Lecamwasam M, Serror P, Wong KW, Sonenshein AL. Bacillus subtilis CodY represses early-stationary-phase genes by sensing GTP levels. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1093–1103. doi: 10.1101/gad.874201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handke LD, Shivers RP, Sonenshein AL. Interaction of Bacillus subtilis CodY with GTP. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:798–806. doi: 10.1128/JB.01115-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkinson MR, Wray LV, Jr, Fisher SH. Regulation of histidine and proline degradation enzymes by amino acid availability in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4758–4765. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4758-4765.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slack FJ, Mueller JP, Strauch MA, Mathiopoulos C, Sonenshein AL. Transcriptional regulation of a Bacillus subtilis dipeptide transport operon. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1915–1925. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher SH, Rohrer K, Ferson AE. Role of CodY in regulation of the Bacillus subtilis hut operon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3779–3784. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3779-3784.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez JM. GTP pool expansion is necessary for the growth rate increase occurring in Bacillus subtilis after amino acids shift-up. Arch Microbiol. 1982;131:247–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00405887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez JM, Dromerick A, Freese E. Response of guanosine 5′-triphosphate concentration to nutritional changes and its significance for Bacillus subtilis sporulation. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:605–613. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.2.605-613.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soga T, Ohashi Y, Ueno Y, Naraoka H, Tomita M, Nishioka T. Quantitative metabolome analysis using capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2003;2:488–494. doi: 10.1021/pr034020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mader U, Hennig S, Hecker M, Homuth G. Transcriptional organization and posttranscriptional regulation of the Bacillus subtilis branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2240–2252. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2240-2252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shivers RP, Sonenshein AL. Bacillus subtilis ilvB operon: an intersection of global regulons. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1549–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tojo S, Satomura T, Morisaki K, Deutscher J, Hirooka K, Fujita Y. Elaborate transcription regulation of the Bacillus subtilis ilv-leu operon involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids through global regulators of CcpA, CodY and TnrA. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1560–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berger BJ, English S, Chan G, Knodel MH. Methionine regeneration and aminotransferases in Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2418–2431. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.8.2418-2431.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomaides HB, Davison EJ, Burston L, Johnson H, Brown DR, Hunt AC, Errington J, Czaplewski L. Essential bacterial functions encoded by gene pairs. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:591–602. doi: 10.1128/JB.01381-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brinsmade SR, Kleijn RJ, Sauer U, Sonenshein AL. Regulation of CodY activity through modulation of intracellular branched-chain amino acid pools. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:6357–6368. doi: 10.1128/JB.00937-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. Contributions of multiple binding sites and effector-independent binding to CodY-mediated regulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:473–484. doi: 10.1128/JB.01151-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meijer WJJ, Salas M. Relevance of UP elements for three strong Bacillus subtilis phage phi29 promoters. Nucl Acids Res. 2004;32:1166–1176. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helmann JD. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma A-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucl Acids Res. 1995;23:2351–2360. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.13.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S, Belitsky BR, Brinker JP, Kerstein KO, Brown DW, Clements JD, Keusch GT, Tzipori S, Sonenshein AL, Herrmann JE. Development of a Bacillus subtilis-based rotavirus vaccine. Clinical Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1647–1655. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00135-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. Role and regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamate dehydrogenase genes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6298–6305. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6298-6305.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srivastava DB, Darst SA. Derepression of bacterial transcription-repair coupling factor is associated with a profound conformational change. J Mol Biol. 2011;406:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selby CP, Sancar A. Molecular mechanism of transcription-repair coupling. Science. 1993;260:53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.8465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Washburn RS, Wang Y, Gottesman ME. Role of E. coli transcription-repair coupling factor Mfd in Nun-mediated transcription termination. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:655–662. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chambers AL, Smith AJ, Savery NJ. A DNA translocation motif in the bacterial transcription-repair coupling factor, Mfd. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:6409–6418. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selby CP, Sancar A. Structure and function of transcription-repair coupling factor. II Catalytic properties. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4890–4895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zalieckas JM, Wray LV, Jr, Ferson AE, Fisher SH. Transcription-repair coupling factor is involved in carbon catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis hut and gnt operons. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1031–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shivers RP, Dineen SS, Sonenshein AL. Positive regulation of Bacillus subtilis ackA by CodY and CcpA: establishing a potential hierarchy in carbon flow. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:811–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zalieckas JM, Wray LV, Jr, Fisher SH. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis acsA gene: position and sequence context affect cre-mediated carbon catabolite repression. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6649–6654. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6649-6654.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park JS, Marr MT, Roberts JW. E. coli transcription repair coupling factor (Mfd protein) rescues arrested complexes by promoting forward translocation. Cell. 2002;109:757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng X, Galinier A, Saxild HH. Catabolite repression of dra-nupC-pdp operon expression in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 2000;146:2901–2908. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-11-2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grandoni JA, Zahler SA, Calvo JM. Transcriptional regulation of the ilv-leu operon of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3212–3219. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3212-3219.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeigler DR, Pragai Z, Rodriguez S, Chevreux B, Muffler A, Albert T, Bai R, Wyss M, Perkins JB. The origins of 168, W23, and other Bacillus subtilis legacy strains. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6983–6995. doi: 10.1128/JB.00722-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis TJ. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belitsky BR, Gustafsson MC, Sonenshein AL, Von Wachenfeldt C. An lrp-like gene of Bacillus subtilis involved in branched-chain amino acid transport. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5448–5457. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5448-5457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qi Y, Hulett FM. PhoP-P and RNA polymerase sigmaA holoenzyme are sufficient for transcription of Pho regulon promoters in Bacillus subtilis: PhoP-P activator sites within the coding region stimulate transcription in vitro. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1187–1197. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Helmann JD. Purification of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase and associated factors. Methods Enzymol. 2003;370:10–24. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daniel RA, Haiech J, Denizot F, Errington J. Isolation and characterization of the lacA gene encoding beta-galactosidase in Bacillus subtilis and a regulator gene, lacR. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5636–5638. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5636-5638.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steinmetz M, Richter R. Plasmids designed to alter the antibiotic resistance expressed by insertion mutations in Bacillus subtilis, through in vivo recombination. Gene. 1994;142:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]