Abstract

In recent years, the use of cynomolgus macaques in biomedical research has increased greatly. However, with the exception of the Mauritian population, knowledge of the MHC class II genetics of the species remains limited. Here, using cDNA cloning and Sanger sequencing we identified 127 full-length MHC class II alleles in a group of 12 Indonesian and 12 Vietnamese cynomolgus macaques. Forty-two of these were completely novel to cynomolgus macaques while 61 extended the sequence of previously identified alleles from partial to full-length. This more than doubles the number of full-length cynomolgus macaque MHC class II alleles available in GenBank, significantly expanding the allele library for the species and laying the groundwork for future evolutionary and functional studies.

Keywords: Macaca fascicularis, cynomolgus macaques, MHC, immunogenetics

Macaques are useful experimental hosts for a variety of human diseases and are frequently used in pathogenesis and vaccine research. Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta; Mamu) from India have traditionally been the preferred species for such studies, but the growing demand for these animals has led to shortages, especially in the field of HIV/AIDS research (Cohen 2000). Researchers are increasingly utilizing the cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis; Mafa) as an alternative non-human primate species. Cynomolgus macaques are closely related to rhesus macaques, but are smaller and more widely available. They have been used for studies of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, plague, and dengue as well as in transplantation and drug toxicity research (Capuano et al. 2003; Guirakhoo et al. 2004; Van Andel et al. 2008; Aoyama et al. 2009; Chamanza et al. 2010; Greene et al. 2010; Willer et al. 2010).

Gene products of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) play a critical role in host immune responses to different pathogens. The most studied gene products encoded by the MHC are the classical class I and class II proteins. MHC class II molecules are expressed as heterodimers consisting of alpha and beta chains that are encoded by A and B genes, respectively. Found on antigen-presenting cells, these molecules display peptides to CD4 T-cells. A number of studies have described associations between specific human DP, DQ, and DRB alleles; HIV susceptibility; and HIV disease progression (Roe et al. 1999; MacDonald et al. 2000; Malhotra et al. 2001; Vyakarnam et al. 2004; Hardie et al. 2008). Some studies also document correlations between MHC class II genetics and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) disease progression in both rhesus and cynomolgus macaques (Sauermann et al. 1997; Sauermann et al. 2000; Giraldo-Vela et al. 2008; Mee et al. 2009). MHC class II genetics presumably also affect immune responses to pathogens (eg. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, influenza virus) against which a CD4 T-cell response in known to play an important role (Flynn 2004, Sant et al. 2007). They therefore have the potential to influence the results of vaccine and pathogenesis studies. In addition, characterization of additional MHC class II alleles may improve our understanding of what constitutes an effective CD4 T-cell response against these pathogens.

Researchers distinguish between several genetically distinct geographic populations of cynomolgus macaques: mainland Southeast Asian, Indonesian, Filipino, and Mauritian (Blancher et al. 2008; Stevison and Kohn 2008). Of all of these geographic populations, only the MHC genetics of the Mauritian population have been comprehensively characterized; this group has limited MHC genetic diversity, making it extremely useful for studies requiring cohorts of MHC-identical animals (O’Connor et al. 2007; Wiseman 2007; Greene et al. 2008; Budde et al. 2010). Nonetheless, biomedical researchers continue to use non-Mauritian cynomolgus macaques. During FY09, for example, only 19% of the cynomolgus macaques imported to the U.S. came from Mauritius (R. Mullan, personal communication, 2010. In spite of this widespread use of non-Mauritian cynomolgus macaques, only a handful of studies have examined the MHC class II genetics of these animals, and none of these studies investigated the DPA locus (Leuchte et al. 2004; Blancher et al. 2006; Sano et al. 2006; Aarnink et al. 2010; Ling et al. 2011).

In order to expand the MHC class II allele library for cynomolgus macaques, we used complementary DNA (cDNA) cloning and sequencing to characterize the full-length sequences of alleles at all six MHC class II loci in 12 Indonesian and 12 Vietnamese cynomolgus macaques. These two populations directly account for 13% of cynomolgus macaques imported to the United States during FY2009. Additionally, they represent a likely original source of the non-native cynomolgus macaques imported from Chinese facilities (59% of FY2009 total) (R. Mullan, personal communication, 2010). In order to increase our chances of identifying novel alleles, we aimed to study a diverse set of animals. The wide variety of STR haplotypes present in the Indonesian animals and MHC class I haplotypes in the Vietnamese animals suggests that the individuals were not closely related to one another (data not shown). We can therefore assume that the animals examined are relatively representative of their respective populations, though the cohorts’ small size limits the degree to which data can be generalized to the population level.

Samples from the Indonesian animals were provided by the Washington National Primate Research Center, Cerus Corporation, and the Wake Forest University Primate Center. One animal came from Jakarta while the rest were imported from a natural habitat breeding facility on Tinjil island, Indonesia and from two breeding colonies at which the majority of animals had Sumatran origins. Samples from 12 Vietnamese cynomolgus macaques, imported by Covance, Inc. were provided by Battelle Biomedical Research Center. Methods used were similar to those described previously (O’Connor et al. 2007). Briefly, mRNA was isolated from whole blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells, reverse transcribed to form cDNA, and then amplified using a subset of the locus-specific primers listed in O’Connor et al. (2007). PCR products were then ligated into a cloning vector, propagated in E. coli, and sequenced using four primers—two internal primers specific to each locus and two primers flanking the cDNA inserts. These sequences were assembled and analyzed using CodonCode Aligner software (CodonCode, Dedham, MA). Novel full-length sequences were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers are listed in Table 1) as well as to the IMGT/MHC Non-human Primate Immuno Polymorphism Database-MHC (IPD-MHC) for official nomenclature (Robinson et al. 2003). The submitted DRB sequences lacked the first base of the open reading frame because it was included as the 3′ nucleotide of the forward primer. In order to avoid characterizing PCR artifacts as novel alleles, putative novel sequences were only considered legitimate when at least three identical full-length clones were observed.

Table 1.

Novel full-length Mafa alleles

| Mafa allele name | Accession # | Animals | Animal origin(s) | Accession #(s)–identical Mafa sequence(s) | Origin(s)–identical Mafa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPA1*02:06 | HM580025 | DR011 | Vietnam | None | |

| DPA1*02:07 | HM580026 | DR012 | Vietnam | none | |

| DPA1*02:08:01 | HM580029 | DR017 | Vietnam | none | |

| DPA1*02:08:02 | HM579970 | CE06 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*02:09 | HM580030 | DR014, DR019 | Vietnam | none | |

| DPA1*02:10 | HM580031 | DR018 | Vietnam | none | |

| DPA1*02:11 | HM579965 | CE28 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*02:12 | HM579966 | IN10 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*02:13 | HM579967 | IN10 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*02:14 | HM579968 | IN04, CE06 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*02:15 | HM579971 | CE03 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*02:16 | HM579972 | CE16, WF01 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*02:17 | HM579974 | WF05 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*04:02 | HM579969 | CE23, IN01, WF01 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*06:01 | HM580027 | DR012 | Vietnam | none | |

| DPA1*07:03 | HM580028 | DR015 | Vietnam | none | |

| DPA1*07:04 | HM579964 | CE12, CE28 | Indonesia | none | |

| DPA1*08:01 | HM580032 | DR015 | Vietnam | none | |

| DPA1*09:01 | HM580024 | DR009 | Vietnam | none | |

|

| |||||

| DPB1*01:01:01 | HM580034 | DR009 | Vietnam | AB235856 (1) | In, Vi |

| DPB1*01:01:02a | HM580042 | DR010 | Vietnam | AB235856 (1) | In, Vi |

| DPB1*02:01:01 | HM580036 | DR012, DR016 | Vietnam | AB235857 (1), AM086061 (2) | Vi |

| DPB1*06 | HM579979 | CE06 | Indonesia | AB235861 (1) | In |

| DPB1*09 | HM580039 | DR016 | Vietnam | AB235864 (1), D13335 (3) | Vi |

| DPB1*10 | HM580037 | DR013, DR014, DR020 | Vietnam | AB235865 (1), D13336 (3) | Vi |

| DPB1*13 | HM580041 | DR019 | Vietnam | AB235868 (1), HM371245 (4) | In, Ph, Vi |

| DPB1*14 | HM579977 | CE28, IN10, IN11 | Indonesia | AB235869 (1), AM086066 (2) | In |

| DPB1*17 | HM580038 | DR017 | Vietnam | AB235872 (1), HM371252 (4) | Vi |

| DPB1*20 | HM580035 | DR011, CE06 | Both | AB235875 (1), AM086062 (2), HM153016 (4) | In, Ph, Vi |

| DPB1*22 | HM579982 | CE03 | Indonesia | AB235877 (1), AM086165 (2) | In, Ph |

| DPB1*32 | HM579986 | IN11 | Indonesia | AB235887 (1), HM371251 (4) | In, Vi |

| DPB1*51 | HM579978 | IN10 | Indonesia | HM153013 (4) | Vi |

| DPB1*56 | HM580040 | DR010 | Vietnam | none | |

| DPB1*57 | HM579981 | DR020, CE23, IN01, WF01 | Both | none | |

| DPB1*58 | HM579983 | CE16, WF01 | Indonesia | none | |

|

| |||||

| DQA1*01:03:02 | HM580044 | DR009, DR010, DR017, CE26 | Both | AM086164 (2) | |

| DQA1*01:09 | HM579992 | CE03 | Indonesia | none | |

| DQA1*01:10 | HM579993 | CE23 | Indonesia | none | |

| DQA1*01:11a | HM579995 | IN04, WF01 | Indonesia | AM086164 (2) | |

| DQA1*01:12 | HM580050 | DR016 | Vietnam | none | |

| DQA1*05:01 | HM580046 | DR011, DR018, CE06 | Both | AM086053 (2) | |

| DQA1*05:03:02 | HM579988 | DR012, DR020, IN10, CE23 | Both | none | |

| DQA1*05:05 | HM580047 | DR012 | Vietnam | none | |

| DQA1*05:06 | HM580051 | DR020 | Vietnam | none | |

| DQA1*24:04 | HM579990 | IN01 | Indonesia | none | |

| DQA1*24:05 | HM579991 | DR009, DR018, CE12 | Both | none | |

| DQA1*26:01 | HM580049 | DR013 | Vietnam | M76208 (5) | |

| DQA1*26:04 | HM580048 | DR014, DR019 | Vietnam | none | |

| DQA1*26:06a | HM580045 | DR011, CE16 | Both | M76208 (5) | |

|

| |||||

| DQB1*06:07:01 | HM579998 | IN04, WF01 | Indonesia | AJ308055 (6) | |

| DQB1*06:13 | HM580005 | WF05 | Indonesia | AJ308061 (6), HM153002 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*06:14 | HM579999 | DR016, IN04, WF05 | Both | AJ308062 (6), HM371235 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*06:16 | HM580052 | DR009 | Vietnam | GQ266371 (7), HM371234 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*06:18 | HM580003 | CE16, CE23, WF01 | Indonesia | GQ266374 (7) | |

| DQB1*06:19 | HM580060 | DR010 | Vietnam | GQ266375 (7), HM153001 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*06:26 | HM580004 | CE23 | Indonesia | GQ266382 (7), HM371232 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*06:31 | HM580059 | CE23 | Vietnam | none | |

| DQB1*06:32 | HM580062 | DR019 | Indonesia | none | |

| DQB1*15:03 | HM580057 | DR010, DR020 | Vietnam | AJ308063 (6), HM371225 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*15:04 | HM580061 | DR020 | Vietnam | none | |

| DQB1*17:02 | HM580055 | DR012 | Vietnam | X57753 (8), GQ266364 (7), HM153009 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*17:03 | HM580001 | DR011, DR017, CE06 | Both | AJ308065 (6), HM371227 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*17:07:01 | HM580054 | DR011, CE16 | Both | GU130498 (7), HM153012 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*18:05 | HM580000 | CE12, IN01 | Indonesia | AJ308072 (6) | |

| DQB1*18:09 | HM580053 | DR009, DR015 | Vietnam | GU130499 (7), HM371239 (4) | Vi |

| DQB1*18:13 | HM580056 | DR013 | Vietnam | GU130503 (7) | |

| DQB1*18:20 | HM580058 | DR019 | Vietnam | none | |

| DQB1*18:21 | HM580002 | CE03 | Indonesia | none | |

|

| |||||

| DRA*01:01:07 | HM580064 | DR013 | Vietnam | AB306655 (7), AY591919 (9), EU877205 (10) | |

| DRA*01:01:08 | HM580067 | DR015 | Vietnam | EU921294 (10) | |

| DRA*01:03:05 | HM580066 | DR016 | Vietnam | EU877206 (10) | |

| DRA*01:04:01:01 | HM580065 | DR010, DR012, DR013, DR017, DR019, DR020 | Vietnam | AB306656 (7) | |

| DRA*02:01:04 | HM580011 | CE16 | Indonesia | none | |

|

| |||||

| DRB*W1:01 | HM580068 | DR009, DR011, DR012, DR013, DR017, IN11 | Both | AF492309 (11), AY340677 (12) | Ch, Ph |

| DRB*W1:02 | FJ919740 | DR017, DR018, CE06 | Both | AF492306 (11), AY340683 (12) | Ch, Ph |

| DRB*W2:06 | FJ919741 | DR011, DR017, DR018, CE06 | Both | EF175105 (7), FN433714 (7) | In, Vi |

| DRB*W3:03:01 | HM580016 | CE23 | Indonesia | AM086041 (2), EF175140 (7) | In |

| DRB*W3:05 | HM580073 | DR013, DR014 | Vietnam | AM086043 (2), EF175129 (7) | In |

| DRB*W3:06 | FJ919732 | IN04 | Indonesia | AM086044 (2), EF175139 (7) | In |

| DRB*W4:03 | HM580075 | DR019 | Vietnam | DQ363298 (7), DQ156968 (13) | Vi |

| DRB*W4:04 | HM580074 | DR012 | Vietnam | DQ363267 (7), DQ777754 (15), HQ148690 (7) | Ch, Vi |

| DRB*W7:02 | FJ919739 | CE12 | Indonesia | AM086046 (2), EF175122 (7), HM153072 (7) | Ch, In, Vi |

| DRB*W7:05 | HM580013 | CE03 | Indonesia | FN433704 (16) | |

| DRB*W7:07a | HM580014 | CE16 | Indonesia | AM086046 (2), EF175122 (7) | In, Vi |

| DRB*W25:03 | HM580076 | DR019 | Vietnam | DQ156970 (13), EF175126 (7) | In, Vi |

| DRB*W26:01:01 | HM580078 | DR015 | Vietnam | DQ363270 (7), FN433706 (7), HM153074 (7) | Ch, Vi |

| DRB*W26:02:01 | FJ919733 | IN04, WF01 | Indonesia | AM911048 (7), DQ363300 (7), EF175132 | In |

| DRB*W27:01 | FJ919726 | CE28 | Indonesia | AY340671 (12), DQ363277 (7), HM153055 (7) | Ch, Vi |

| DRB*W33:01:02 | FJ919736 | IN01 | Indonesia | none | |

| DRB*W36:02:02 | FJ919730 | DR19, IN01, IN10 | Both | AM910925 (14) | |

| DRB*W40:01 | HM580017 | CE23 | Indonesia | DQ156971 (13) | |

| DRB*W64:01 | HM580072 | DR012 | Vietnam | DQ363274 (7), FN433702 (7) | Vi |

| DRB*W66:01 | FJ919727 | CE28 | Indonesia | AM910926 (14) | |

| DRB*W73:01 | FJ919731 | IN10 | Indonesia | none | |

| DRB1*03:03 | HM580069 | DR009, DR014, DR017 | Vietnam | AY340673 (12), DQ363296 (7) | Ch, Vi |

| DRB1*03:06:02 | HM580071 | DR011 | Vietnam | none | |

| DRB1*03:29 | HM580070 | DR011 | Vietnam | none | |

| DRB1*03:30a | HM580020 | IN11 | Indonesia | AY340673 (12), DQ363296 (7) | Ch, Vi |

| DRB1*04:05 | HM580077 | DR020 | Vietnam | DQ363260 (7) | Vi |

| DRB1*04:11 | FJ919729 | IN01, IN10 | Indonesia | AM911050 (14), EF175117 (7) | In |

| DRB1*04:14 | HM580015 | CE16 | Indonesia | none | |

| DRB1*07:02:02 | FJ919738 | CE12 | Indonesia | DQ363264 (7), FN433726 (7) | Vi |

| DRB1*10:12 | FJ919737 | IN01 | Indonesia | HM236222 (7) | |

Denotes alleles which extended previously available sequence but were not given the same name because it had already been assigned to a different full-length sequence with the same exon 2.

Mafa alleles for which full-length sequence was not previously available, including extensions of previously named alleles. “Both” denotes alleles found in both the Indonesian and Vietnamese cohorts. Identical Mafa sequences for which accession numbers are listed are limited to exon 2 with the exception of the DRA alleles. The origin information for identical Mafa sequences was taken from the corresponding publication(s) and/or GenBank record(s). Abbreviations used are as follows: Ch=China, In=Indonesia, Ph=Philippines, Vi=Vietnam. References for accession numbers are (1) Sano et al. 2006, (2) Doxiadis et al. 2006, (3) Hashiba et al. 1993, (4) Ling et al. 2011, (5) Kenter et al. 1992, (6) Otting et al. 2002, (7) unpublished, various sources (8) Gaur et al. 1992, (9) Senju et al. 2007, (10) Aarnink et al. 2010, (11) Blancher et al. 2006, (12) Leuchte et al. 2004, (13) Mee et al. 2008, (14) De Groot et al. 2008, (15) Wei et al. 2007, (16) Doxiadis et al. 2010.

In the 24 animals studied, we identified 127 distinct full-length MHC class II alleles, 43 of which were detected in more than one animal. Since these were cDNA sequences, all are actively transcribed and have the potential to form functional class II molecules. Twenty-four of these 127 transcripts were identical to previously identified full-length Mafa sequences (Supplemental Table 1). The remaining 103 alleles represented novel full-length Mafa sequences. Of these, 61 extended the sequence of known alleles for which the entire open reading frame was not previously available (Table 1). In five instances, two distinct full-length sequences extended a single previously described exon 2 sequence. The other 42 sequences (Table 1) were completely novel to cynomolgus macaques and were named by the NHP Nomenclature Committee based on alignment with known sequences (Robinson et al. 2003). Twelve of these novel transcripts were identical to previously identified Mamu class II nucleotide sequences and three perfectly matched alleles previously identified in stump-tailed macaques (Macaca arctoides; Maar) (Supplemental Table 2). This result is consistent with previous work documenting a high level of MHC class II allele sharing between rhesus and cynomolgus macaques and further supports the hypothesis that the macaque MHC class II has undergone conservative selection (Doxiadis et al. 2006). More of these alleles are potentially shared with other macaque species, but our ability to detect such sharing is hindered by the currently limited allele libraries for these species.

The data presented here triples the number of full-length nucleotide sequences of Mafa alleles in GenBank at all MHC class II loci except DRB. As of November 2010, a total of 36 full-length Mafa coding sequences were available for the DPA, DPB, DQA, DQB, and DRA loci combined. We describe 73 additional full-length sequences at these loci, bringing the total to 109. The DRB locus has been more extensively studied to date, with 37 full-length DRB coding sequences available in GenBank as of November 2010. We report an additional 30 DRB allele sequences, nearly doubling the total in GenBank. These full coding sequences are a prerequisite to the construction of cell lines expressing a single MHC class II molecule and MHC class II-peptide tetramers. Such reagents have informed the study of CD4 T-cell responses to in both humans and rhesus macaques (Kuroda et al. 2000; Dzuris et al. 2001; Giraldo-Vela et al 2008). To our knowledge, studies of SIV-specific CD4 T-cell responses have not yet been conducted in cynomolgus macaques. The expanded number of full-length Mafa MHC class II coding sequences presented here should aid researchers in developing the reagents necessary for investigation of CD4 T-cell responses in cynomolgus macaques.

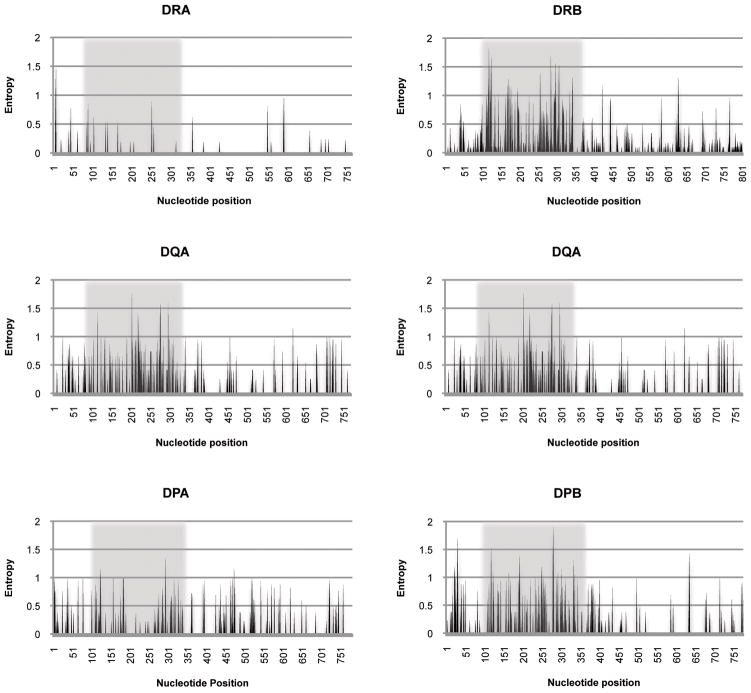

Previous studies of the DPB, DQA, DQB, and DRB loci have largely been limited to the second exon, which encodes the highly variable peptide-binding region of these MHC molecules (Leuchte et al. 2004; Blancher et al. 2006; Doxiadis et al. 2006; Sano et al. 2006; Ling et al. 2011). However, sequencing of exon 2 alone may not always provide a complete picture of host MHC class II genetics since alleles may differ from one another only outside of this exon. We used the expanded library of full-length Mafa MHC class II alleles resulting from this study to evaluate the degree of resolution of unique alleles which can be achieved by exon 2-based genotyping for the current database of known alleles. For the analysis, we combined our data with all unique sequences available in GenBank as of November 2010 that extended beyond exon 2. A visual representation of the nucleotide variability across each MHC class II locus is shown in Figure 1. These plots demonstrate that all six MHC class II loci contain different degrees of variation outside of exon 2. It was more difficult to distinguish between the A alleles by looking only at exon 2 because there was extensive variability throughout the coding region. In the most extreme example, 26 of 33 DRA sequences (79%) were identical across exon 2 to at least one other allele. This observation was not surprising given the limited polymorphism at this locus (de Groot et al. 2004; Aarnink et al. 2010). Even the DPA and DQA loci, which are more variable, showed significant levels of ambiguity when only exon 2 was examined. Twelve of 27 (44%) DPA and 12 of 24 (50%) DQA alleles could not be distinguished from one another on the basis of exon 2 sequences alone. Although the variability of the class II B loci is more concentrated in exon 2, complete differentiation was not possible for any of the loci. The DQB alleles were easiest to distinguish; only two out of a total of 27 DQB alleles (7%) shared exon 2 sequence. Differentiating between DRB alleles was slightly more difficult as 10 of 78 (13%) sequences were identical to at least one other allele across exon 2. At the DPB locus, over one fifth – 6 of 27 (22%) – of exon 2 sequences could not be assigned to a single specific allele. As the library of full-length MHC class II nucleotide sequences grows, the number of alleles with identical exon 2 sequences will likely increase. Though the biological significance of differences outside of exon 2 remains unclear, our analysis suggests that full-length sequencing can be more precise and informative than that of exon 2 alone, particularly at the DPA, DPB, DQA, and DRA loci.

Fig. 1.

We also sought to examine the sharing of MHC class II alleles between geographic populations of cynomolgus macaques. This was most pronounced between the Indonesian and Vietnamese groups. In total, we detected evidence of 22 alleles shared between Indonesian and Vietnamese cynomolgus macaques that had not been previously associated with animals from both regions. Eighteen alleles were detected in both cohorts of animals used in this study, fifteen of which were not previously known to be common to both populations (Table 1, Supplemental Table 1). An additional seven were found in only one of the two populations described here, but had previously been documented in the other. The shared alleles may have originated prior to the initial isolation of the Indonesian population or may have resulted from gene flow across the Sunda shelf during later periods of lowered sea levels (Voris 2000; Sathiamurthy and Voris 2006). Significant allele sharing was also evident between animals from Indonesia and Mauritius; within our small Indonesian cohort, we documented twelve class II cDNA sequences identified previously in cynomolgus macaques from Mauritius. Only two of these (Mafa-DPB1*21 and Mafa-DPB1*29) had been previously associated with the Indonesian population. Such sharing further supports the hypothesis that the Mauritian population was founded by cynomolgus macaques from Indonesia (Tosi and Coke 2007; Bonhomme et al. 2008).

In summary, given the potential of the MHC to serve as a confounding variable in experiments, it is prudent to consider class I and II genotyping, preferably using full-length sequences, of animals used in vaccine or pathogenesis studies. The 103 novel full-length sequences described here greatly expand the Mafa MHC class II allele library and will aid the development of reagents for MHC genotyping. This growing library will also improve future disease-association studies and provides an important foundation for functional studies of CD4 T-cell responses to a diversity of pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant 1 R24 RR021745-01A1. Additional support was provided by NIH grant number P51 RR000167 to the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison. This research was conducted in part at a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program grant numbers RR15459-01 and RR020141-01. We thank Battelle Biomedical Research Center, the Washington National Primate Research Center, the Cerus Corporation, and the Wake Forest University Primate Center for providing samples. Finally, we acknowledge Nel Otting and Natasja de Groot with the Immuno Polymorphism Database for assigning official allele nomenclature and members of the O’Connor laboratory for their helpful discussions.

References

- Aarnink A, Estrade L, Apoil PA, Kita YF, Saitou N, Shiina T, Blancher A. Study of cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) DRA polymorphism in four populations. Immunogenetics. 2010;62:123–136. doi: 10.1007/s00251-009-0421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama A, Ng CY, Millington TM, Boskovic S, Murakami T, Wain JC, Houser SL, Madsen JC, Kawai T, Allan JS. Comparison of lung and kidney allografts in induction of tolerance by a mixed-chimerism approach in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:429–430. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.08.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blancher A, Bonhomme M, Crouau-Roy B, Terao K, Kitano T, Saitou N. Mitochondrial DNA sequence phylogeny of 4 populations of the widely distributed cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis fascicularis) J Hered. 2008;99:254–264. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blancher A, Tisseyre P, Dutaur M, Apoil PA, Maurer C, Quesniaux V, Raulf F, Bigaud M, Abbal M. Study of Cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) MhcDRB (Mafa-DRB) polymorphism in two populations. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme M, Blancher A, Cuartero S, Chikhi L, Crouau-Roy B. Origin and number of founders in an introduced insular primate: estimation from nuclear genetic data. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:1009–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde ML, Wiseman RW, Karl JA, Hanczaruk B, Simen BB, O’Connor DH. Characterization of Mauritian cynomolgus macaque major histocompatibility complex class I haplotypes by high-resolution pyrosequencing. Immunogenetics. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0481-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuano SV, 3rd, Croix DA, Pawar S, Zinovik A, Myers A, Lin PL, Bissel S, Fuhrman C, Klein E, Flynn JL. Experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of cynomolgus macaques closely resembles the various manifestations of human M. tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5831–5844. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5831-5844.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamanza R, Marxfeld HA, Blanco AI, Naylor SW, Bradley AE. Incidences and range of spontaneous findings in control cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) used in toxicity studies. Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38:642–657. doi: 10.1177/0192623310368981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. AIDS research. Vaccine studies stymied by shortage of animals. Science. 2000;287:959–960. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot N, Doxiadis GG, De Groot NG, Otting N, Heijmans C, Rouweler AJ, Bontrop RE. Genetic makeup of the DR region in rhesus macaques: gene content, transcripts, and pseudogenes. J Immunol. 2004;172:6152–6157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot N, Doxiadis GG, de Vos-Rouweler AJ, de Groot NG, Verschoor EJ, Bontrop RE. Comparative genetics of a highly divergent DRB microsatellite in different macaque species. Immunogenetics. 2008;60:737–748. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxiadis GG, de Groot N, de Groot NG, Rotmans G, de Vos-Rouweler AJ, Bontrop RE. Extensive DRB region diversity in cynomolgus macaques: recombination as a driving force. Immunogenetics. 2010;62:137–147. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0422-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxiadis GG, Otting N, de Groot NG, Noort R, Bontrop RE. Unprecedented polymorphism of Mhc-DRB region configurations in rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 2000;164:3193–3199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxiadis GG, Rouweler AJ, de Groot NG, Louwerse A, Otting N, Verschoor EJ, Bontrop RE. Extensive sharing of MHC class II alleles between rhesus and cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:259–268. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzuris JL, Sidney J, Horton H, Correa R, Carter D, Chesnut RW, Watkins DI, Sette A. Molecular determinants of peptide binding to two common rhesus macaque major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. J Virol. 2001;75:10958–10968. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10958-10968.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fooden J. Systematic review of Philippine macaques (Primates, Cercopithecidae: Macaca fascicularis subspp. Fieldiana Zoology (USA) 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JL. Immunology of tuberculosis and implications in vaccine development. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2004;84:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaur LK, Hughes AL, Heise ER, Gutknecht J. Maintenance of DQB1 polymorphisms in primates. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:599–609. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo-Vela JP, Rudersdorf R, Chung C, Qi Y, Wallace LT, Bimber B, Borchardt GJ, Fisk DL, Glidden CE, Loffredo JT, Piaskowski SM, Furlott JR, Morales-Martinez JP, Wilson NA, Rehrauer WM, Lifson JD, Carrington M, Watkins DI. The major histocompatibility complex class II alleles Mamu-DRB1*1003 and -DRB1*0306 are enriched in a cohort of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaque elite controllers. J Virol. 2008;82:859–870. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01816-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JM, Burwitz BJ, Blasky AJ, Mattila TL, Hong JJ, Rakasz EG, Wiseman RW, Hasenkrug KJ, Skinner PJ, O’Connor SL, O’Connor DH. Allogeneic lymphocytes persist and traffic in feral MHC-matched mauritian cynomolgus macaques. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JM, Lhost JJ, Burwitz BJ, Budde ML, Macnair CE, Weiker MK, Gostick E, Friedrich TC, Broman KW, Price DA, O’Connor SL, O’Connor DH. Extralymphoid CD8+ T cells resident in tissue from simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239{Delta}nef-vaccinated macaques suppress SIVmac239 replication ex vivo. J Virol. 2010;84:3362–3372. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02028-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirakhoo F, Pugachev K, Zhang Z, Myers G, Levenbook I, Draper K, Lang J, Ocran S, Mitchell F, Parsons M, Brown N, Brandler S, Fournier C, Barrere B, Rizvi F, Travassos A, Nichols R, Trent D, Monath T. Safety and efficacy of chimeric yellow Fever-dengue virus tetravalent vaccine formulations in nonhuman primates. J Virol. 2004;78:4761–4775. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4761-4775.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RA, Knight E, Bruneau B, Semeniuk C, Gill K, Nagelkerke N, Kimani J, Wachihi C, Ngugi E, Luo M, Plummer FA. A common human leucocyte antigen-DP genotype is associated with resistance to HIV-1 infection in Kenyan sex workers. AIDS. 2008;22:2038–2042. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328311d1a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiba K, Kuwata S, Tokunaga K, Juji T, Noguchi A. Sequence analysis of DPB1-like genes in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) Immunogenetics. 1993;38:462. doi: 10.1007/BF00184530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenter M, Otting N, Anholts J, Leunissen J, Jonker M, Bontrop RE. Evolutionary relationships among the primate Mhc-DQA1 and DQA2 alleles. Immunogenetics. 1992;36:71–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00215282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Lekutis C, Nickerson CE, Lifton MA, Franchini G, Harouse JM, Cheng-Mayer C, Letvin NL. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope epitope-specific CD4(+) T lymphocytes in simian/human immunodeficiency virus-infected and vaccinated rhesus monkeys detected using a peptide-major histocompatibility complex class II tetramer. J Virol. 2000;74:8751–8756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8751-8756.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling F, Wei LQ, Wang T, Wang HB, Zhuo M, Du HL, Wang JF, Wang XN. Characterization of the major histocompatibility complex class II DOB, DPB1, and DQB1 alleles in cynomolgus macaques of Vietnamese origin. Immunogenetics. 2011;63:155–166. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0498-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuchte N, Berry N, Kohler B, Almond N, LeGrand R, Thorstensson R, Titti F, Sauermann U. MhcDRB-sequences from cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) of different origin. Tissue Antigens. 2004;63:529–537. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-2815.2004.0222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald KS, Fowke KR, Kimani J, Dunand VA, Nagelkerke NJ, Ball TB, Oyugi J, Njagi E, Gaur LK, Brunham RC, Wade J, Luscher MA, Krausa P, Rowland-Jones S, Ngugi E, Bwayo JJ, Plummer FA. Influence of HLA supertypes on susceptibility and resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1581–1589. doi: 10.1086/315472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra U, Holte S, Dutta S, Berrey MM, Delpit E, Koelle DM, Sette A, Corey L, McElrath MJ. Role for HLA class II molecules in HIV-1 suppression and cellular immunity following antiretroviral treatment. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:505–517. doi: 10.1172/JCI11275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee ET, Berry N, Ham C, Sauermann U, Maggiorella MT, Martinon F, Verschoor EJ, Heeney JL, Le Grand R, Titti F, Almond N, Rose NJ. Mhc haplotype H6 is associated with sustained control of SIVmac251 infection in Mauritian cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics. 2009;61:327–339. doi: 10.1007/s00251-009-0369-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee ET, Murrell CK, Sauermann U, Wilkinson RC, Cutler K, North D, Heath A, Ladhani K, Almond N, Rose NJ. The Mhc class II DRB genotype of Macaca fascicularis does not influence infection by simian retrovirus type 2. Tissue Antigens. 2008;72:369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2008.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor SL, Blasky AJ, Pendley CJ, Becker EA, Wiseman RW, Karl JA, Hughes AL, O’Connor DH. Comprehensive characterization of MHC class II haplotypes in Mauritian cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:449–462. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0209-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otting N, de Groot NG, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE. Extensive Mhc-DQB variation in humans and non-human primate species. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:230–239. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0461-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Waller MJ, Parham P, de Groot N, Bontrop R, Kennedy LJ, Stoehr P, Marsh SG. IMGT/HLA and IMGT/MHC: sequence databases for the study of the major histocompatibility complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:311–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe DL, Lewis RE, Cruse JM. Association of HLA-DQ and -DR alleles with protection from or infection with HIV-1. Exp Mol Pathol. 2000;68:21–28. doi: 10.1006/exmp.1999.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano K, Shiina T, Kohara S, Yanagiya K, Hosomichi K, Shimizu S, Anzai T, Watanabe A, Ogasawara K, Torii R, Kulski JK, Inoko H. Novel cynomolgus macaque MHC-DPB1 polymorphisms in three South-East Asian populations. Tissue Antigens. 2006;67:297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant AJ, Chaves FA, Krafcik FR, Lazarski CA, Menges P, Richards K, Weaver JM. Immunodominance in CD4 T-cell responses: implications for immune responses to influenza virus and for vaccine design. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:357–368. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathiamurthy E, Voris HK. Maps of Holocene sea level transgression and submerged lakes on the Sunda Shelf. Natural History. 2006;2:1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sauermann U, Krawczak M, Hunsmann G, Stahl-Hennig C. Identification of Mhc-Mamu-DQB1 allele combinations associated with rapid disease progression in rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS. 1997;11:1196–1198. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199709000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauermann U, Stahl-Hennig C, Stolte N, Muhl T, Krawczak M, Spring M, Fuchs D, Kaup FJ, Hunsmann G, Sopper S. Homozygosity for a conserved Mhc class II DQ-DRB haplotype is associated with rapid disease progression in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques: results from a prospective study. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:716–724. doi: 10.1086/315800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senju S, Suemori H, Zembutsu H, Uemura Y, Hirata S, Fukuma D, Matsuyoshi H, Shimomura M, Haruta M, Fukushima S, Matsunaga Y, Katagiri T, Nakamura Y, Furuya M, Nakatsuji N, Nishimura Y. Genetically manipulated human embryonic stem cell-derived dendritic cells with immune regulatory function. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2720–2729. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevison LS, Kohn MH. Determining genetic background in captive stocks of cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) J Med Primatol. 2008;37:311–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2008.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosi AJ, Coke CS. Comparative phylogenetics offer new insights into the biogeographic history of Macaca fascicularis and the origin of the Mauritian macaques. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;42:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Andel R, Sherwood R, Gennings C, Lyons CR, Hutt J, Gigliotti A, Barr E. Clinical and pathologic features of cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) infected with aerosolized Yersinia pestis. Comp Med. 2008;58:68–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voris HK. Field Museum Nat Hist. Chicago, IL 60605 USA: 2000. Maps of Pleistocene sea levels in Southeast Asia: shorelines, river systems and time durations. [Google Scholar]

- Vyakarnam A, Sidebottom D, Murad S, Underhill JA, Easterbrook PJ, Dalgleish AG, Peakman M. Possession of human leucocyte antigen DQ6 alleles and the rate of CD4 T-cell decline in human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Immunology. 2004;112:136–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Wang H, Hou S, Hu S, Fan K, Fan X, Zhu T, Guo Y. DRB genotyping in cynomolgus monkeys from China using polymerase chain reaction -sequence-specific primers. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer DO, Guan Y, Luscher MA, Li B, Pilon R, Fournier J, Parenteau M, Wainberg MA, Sandstrom P, MacDonald KS. Multi-low-dose mucosal simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 challenge of cynomolgus macaques immunized with “hyperattenuated” SIV constructs. J Virol. 2010;84:2304–2317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01995-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.