Abstract

Catalysis of sequential reactions is often envisaged to occur by channeling of substrate between enzyme active sites without release into bulk solvent. However, while there are compelling physiological rationales for direct substrate transfer, proper experimental support for the hypothesis is often lacking, particularly for metabolic pathways involving RNA. Here we apply transient kinetics approaches developed to study channeling in bienzyme complexes, to an archaeal protein synthesis pathway featuring the misaminoacylated tRNA intermediate Glu-tRNAGln. Experimental and computational elucidation of a kinetic and thermodynamic framework for two-step cognate Gln-tRNAGln synthesis demonstrates that the misacylating aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (GluRSND) and tRNA-dependent amidotransferase (GatDE) function sequentially without channeling. Instead, rapid processing of the misacylated tRNA intermediate by GatDE, and preferential elongation factor binding to the cognate Gln-tRNAGln, together permit accurate protein synthesis without formation of a binary protein-protein complex between GluRSND and GatDE. These findings establish an alternate paradigm for protein quality control via two-step pathways for cognate aminoacyl-tRNA formation.

Keywords: protein synthesis, pre-steady state kinetics, amidotransferase, elongation factor, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

Introduction

Channeling of substrates between enzyme active sites provides increased control over metabolic flux, protects labile intermediates from bulk solvent, and allows sequestration of molecular species that may cause toxicity.1,2 Well-characterized examples of channeling exist in multifunctional enzymes, in which the intermediates pass rapidly through sequestered tunnels prior to reacting in the second active site.2 Another class of channeling reactions occurs in macromolecular assemblies of two or more components, that are sufficiently stable to permit substrate transfer without dissociation. Purine biosynthesis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and mitochondrial respiratory chains are among the diverse pathways for which substrate channeling of this type has been identified.3–5 Detailed characterization of metabolic channeling is complementary to systems biology efforts to comprehensively describe protein interaction networks in vivo,6,7 since it provides a functional rationale for the formation of binary and higher-order assemblies.

Channeling also occurs in the maintenance and expression of genetic information, where the process involves both protein and nucleic acid components. In particular, channeling of aminoacyl-tRNA for protein synthesis has been demonstrated in vivo in transiently permeabilized mammalian cells: exogenously added aminoacyl-tRNAs are unavailable for protein synthesis, while endogenous tRNAs are continuously reutilized.8,9 This suggests that protein synthesis occurs within a highly organized supramolecular network. Further, in higher eukaryotes nine of the twenty aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRS) together with three RNA-binding proteins associate in a cytoplasmic multi-tRNA synthetase complex (MSC).10 Arginyl-tRNA is more efficiently used in protein synthesis when produced by a higher molecular weight form of arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS) associated with the MSC, as compared with free ArgRS, consistent with a channeling model.11 Channeling may also occur at other stages of protein synthesis: in the association of aminoacyl-tRNA with elongation factors,12 in the transport of tRNA out of the nucleus to the ribosome,13 and in post-translational processes associated with protein folding and translocation.14, 15

In lower eukaryotes, bacteria and archaea, associations among aaRS are, so far as is known, limited to smaller assemblies of two to five enzymes.6,16–18 Further, experiments comparable to those performed on mammalian cells, to examine tRNA channeling in vivo, have not been performed. Nonetheless, channeling has been proposed in a variety of contexts, particularly for two-step pathways to cognate aminoacyl-tRNA. In many bacteria, eukaryotic organelles and all archaea, Gln-tRNAGln and Asn-tRNAAsn synthesis proceeds via formation of a misacylated Glu-tRNAGln or Asp-tRNAAsn intermediate in a reaction catalyzed by a non-discriminating tRNA synthetase (aaRSND).19–21 Both GluRSND and AspRSND maintain high selectivity for the cognate amino acid, but each possesses broadened tRNA specificity for two isoacceptor tRNA families (Glu/Gln and Asp/Asn, respectively). Although the structural and mechanistic origins of the broadened tRNA specificity are poorly understood, these enzymes appear very likely to function via a two-step ATP-dependent reaction featuring an activated aminoacyl adenylate intermediate, similar to canonical tRNA synthetases.22

The misacylated tRNAs are then converted to Gln-tRNAGln and Asn-tRNAAsn by tRNA-dependent amidotransferases (AdT).23,24 Two families of AdT enzymes are known: GatCAB is present in most cells employing the two-step pathway, and can act as both Glu-Adt and Asp-AdT, whereas GatDE is present exclusively in Archaea and functions only with Glu-tRNAGln as substrate.23,24 In a three-step reaction, a nitrogen donor (glutamine or asparagine) is first processed by the GatA or GatD subunit to release ammonia, which is then shuttled through an intramolecular tunnel to emerge in the GatB or GatE active site. GatB/GatE binds the misacylated 3′-end of tRNAAsn or tRNAGln, and phosphorylates the side-chain carboxylate of the esterified amino acid on the tRNA in an ATP-dependent reaction, enabling attack of the translocated ammonia (with release of phosphate) to generate cognate aminoacyl-tRNA.25–27

These two-step pathways appear to be prime candidates for channeling, since sequestration of misacylated tRNA could alleviate possible toxicity associated with misincorporation into protein. Indeed, recent crystal structures of ternary GatCAB:AspRSND-tRNAAsn and GatCAB:GluRSND-tRNAGln complexes have directly demonstrated formation of a macromolecular assembly between the tRNA substrate and the two enzymes, corroborating prior observation of ternary protein-tRNA complexes in solution.28–30 These data provided the basis for postulating the existence of a “transamidosome”, which is proposed to directly channel misacylated tRNAs from the aaRSND to GatCAB. The model for function includes unimolecular conformational rearrangements in this ternary complex, by which the tRNA 3′-end is redirected from the GluRSND active site to that of GatCAB while maintaining binding.30 Although crystal structures of ternary complexes have not been determined in the GatDE system, biochemical evidence for GluRSND-GatDE and GluRSND-GatDE-tRNAGln binary and ternary complex formation has been reported.31 Molecular modeling based on the GatCAB ternary complexes was also used to infer that ternary complex formation by GatDE is plausible.30

Although formation of complexes is consistent with the notion of substrate channeling, explicit transfer of misacylated tRNA from aaRSND to the amidotransferase has not been demonstrated for any two-step aminoacylation pathway. Thus, the possibility remains that misacylated tRNA dissociates into solution prior to rebinding the amidotransferase. In the GatDE experiments, the proposed GatDE-GluRSND binary complex is apparently unstable during the course of the reaction, and neither GluRSND nor GatDE is reported to affect the activity of its partner enzyme.31 Hence, alternative mechanisms to maintain protein quality control and to avoid potential toxicity of misacylated tRNA, in the absence of channeling, must be considered.

To provide a more definitive interrogation of channeling in two-step aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis, we have applied pre-steady state kinetic approaches developed in our laboratory for the study of discriminating aaRS,32 to the two-step GluRSND-GatDE pathway from Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus – which was also the subject of the prior analyses.27,31 Our experimental approach relies on applying the strategy developed for study of bifunctional enzymes such as thymidylate synthase – dihydrofolate reductase,33 where channeling was demonstrated by comparing and analyzing separate rapid kinetics measurements for each independent enzyme and for the full two-step reaction. Other studies taking this approach have demonstrated the absence of channeling in systems where its existence had been presumed.34 By combining these measurements with kinetic simulations, we have generated a comprehensive thermodynamic and kinetic scheme for the two-step pathway, which demonstrates to a high degree of confidence that the GluRSND and GatDE function independently and that the misacylated tRNA is not sequestered. Thus, in contrast to the earlier findings,31 our data do not support the existence of a GatDE transamidosome in Archaea. Instead, we suggest that specific and rapid ATP-dependent conversion of Glu-tRNAGln to Gln-tRNAGln by GatDE, and binding of translation elongation factor 1α (EF-1α) to Gln-tRNAGln and not to Glu-tRNAGln, together provide sufficient discrimination against delivery of Glu-tRNAGln to the ribosome. These experiments offer the first definitive evaluation of channeling for any RNA-based metabolic pathway.

Results

Kinetic dissection of Gln-tRNAGln formation

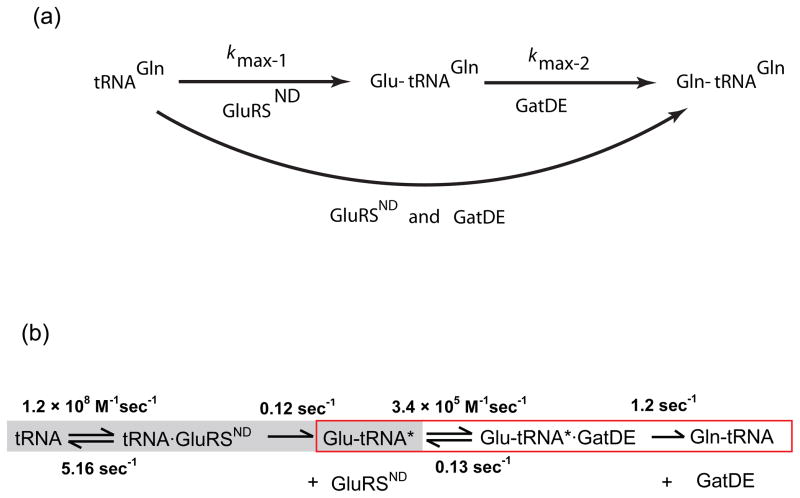

Our strategy for detailed study of the GluRSND-GatDE pathway consists of performing three sets of pre-steady state kinetics experiments. First, we measure the maximum rate constant (kmax-1) for GluRSND-mediated Glu-tRNAGln formation from tRNAGln in single turnover reactions (Fig. 1). Next, we perform analogous experiments to measure kmax-2 for GatDE-mediated Gln-tRNAGln formation from Glu-tRNAGln. Finally, we monitor formation of Glu-tRNAGln and Gln-tRNAGln in the presence of both GluRSND and GatDE, on timescales permitting observation of a Glu-tRNAGln intermediate if it indeed accumulates. Further measurements of second-order association steps and first-order dissociation steps are also made. We employ a reaction scheme incorporating these rate constants and build models for both channeled and dissociative pathways using kinetic simulations. Comparison of simulated plots and observed data then allows distinguishing a two-step dissociative mechanism from channeling mechanisms, as demonstrated previously for small-molecule metabolites in bifunctional enzymes.33,34 If direct channeling obtains, the simplest expectations are that the formation of Gln-tRNAGln is limited only by the formation of Glu-tRNAGln (kmax-1), and that no accumulation of the Glu-tRNAGln intermediate in the presence of both enzymes will be observed (Fig. 1a). In contrast, accumulation of Glu-tRNAGln would suggest lack of channeling.

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of the two-step pathway for Gln-tRNAGln formation in the archaeon M. thermautotrophicus. (a) Experimental design used to investigate the possibility that the intermediate Glu-tRNAGln is channeled from GluRSND to GatDE. (b) Summary of rate constants for individual steps in the two-step pathway for Gln-tRNAGln synthesis, derived from experiments presented in thjis manuscript.

Rapid release of Glu-tRNAGln product from GluRSND

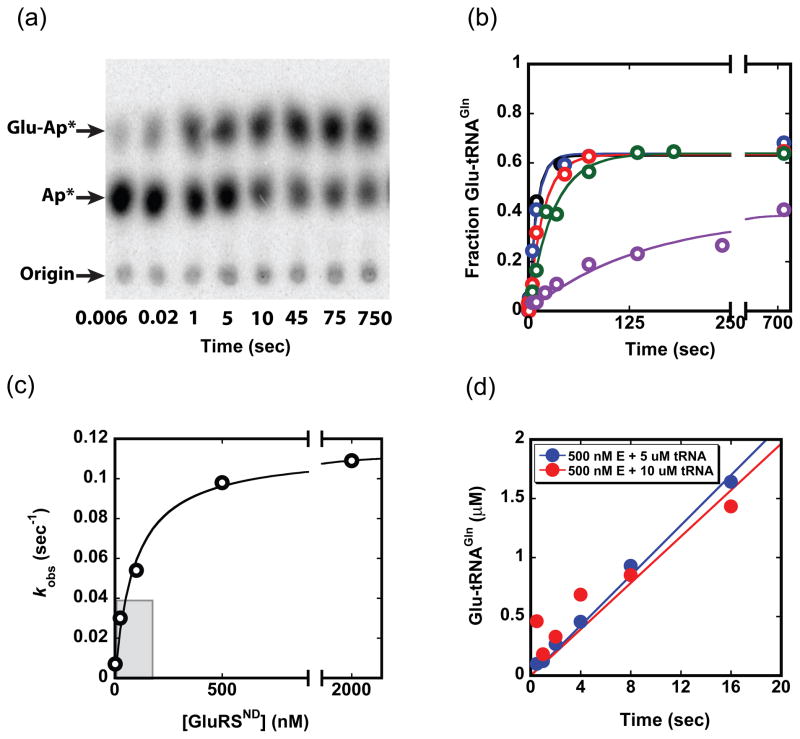

We began by dissecting the steps of Glu-tRNAGln formation by GluRSND, employing kinetic approaches similar to those developed for quantitative characterization of E. coli GlnRS in our laboratory (Fig. 2).32 Product formation with time was monitored in single turnover reactions with molar excess of GluRSND over tRNAGln, at varying concentrations of enzyme, and at saturating ATP and glutamate concentrations (10 mM and 50 mM, respectively) (Fig. 2b). Replots of this data revealed a linear dependence of kobs with GluRSND concentration under subsaturating conditions, allowing extraction of a second-order rate constant. The numerical value of this constant, 2.6 × 106 M−1sec−1, is equivalent to the kcat/Km that we previously reported by monitoring steady-state reactions (Fig. 2c – shaded portion).35 This value places a lower limit on the second-order rate constant for binding (kon) of GluRSND to tRNAGln in the forward reaction pathway. At higher concentrations of GluRSND, saturation is observed (Fig. 2c). The kmax of 0.12 sec−1 is identical within error to the previously determined kcat,35 suggesting that either the rate of the chemical steps on the enzyme, or a first-order conformational rearrangement prior to catalysis, is rate-limiting for the reaction. These data also allow determination of the equilibrium dissociation constant for tRNA at 40 nM, identical to the value previously reported based on fluorescence anisotropy measurements of the binary complex.31 We also find that inclusion of GatDE in GluRSND single-turnover reactions, at equimolar concentration, does not influence the rate of product formation (data not shown).31

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of the tRNAGln aminoacylation reaction. (a) Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) separation of substrate and products from a single turnover reaction at 500 nM enzyme (quantitated in b). Plateau aminoacylation levels for the reaction are consistemtly in the 60–70% range. (b) Time traces of product formation at enzyme concentrations of 2 nM (purple), 25 nM (green), 100 nM (red), 500 nM (blue) and 2 μM (black). The tRNAGln concentration in each reaction is < 1 nM. Curves are fit to F = Fmax(1−e−kt), where F is the fraction Glu-tRNAGln formed, Fmax is the maximum (plateau) value of F, k is the rate constant (sec−1) and t is time (sec). (c) Plot of kobs values obtained from the data in panel (b) as a function of GluRSND concentration; from this plot we derive kmax of 0.12 ± 0.01 sec−1 and K1/2 of 43 ± 18 nM. The curve is fit to: kobs = kobs,max[GluRSND]/(K1/2 + [GluRSND]). (d) Pre-steady state kinetic timecourses at 500 nM GluRSND and either 5 μM (blue) or 10 μM tRNAGln (red).

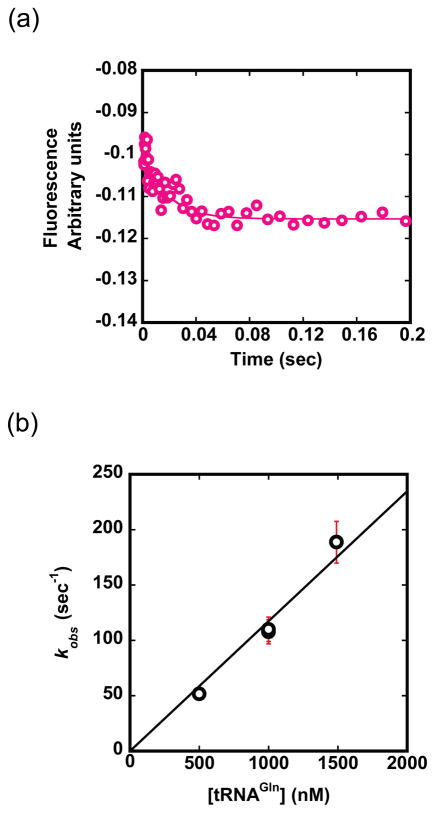

To further evaluate the hypothesis that an early step is rate-limiting, we monitored product formation under conditions that would allow observation of a pre-steady state burst followed by multiple turnovers. No burst was observed at 500 nM enzyme and 5–10 μM tRNAGln, and linear fits to the data allowed derivation of kcat identical to that obtained in steady-state kinetics (Fig. 2d).35 The absence of a characteristic burst at either tRNAGln concentration confirms that Glu-tRNAGln dissociation from GluRSND occurs rapidly and is not rate-limiting for the overall reaction. To complete the minimal reaction scheme, we also measured the elementary rate constants for association and dissociation of tRNAGln from GluRSND (Figs. 1b and 3). To measure kon, we monitored changes in the intrinsic Trp fluorescence of GluRSND upon addition of tRNAGln, in the absence of Glu and ATP.36 Other filter-binding experiments suggest that Kd is not significantly affected by the presence of glutamate and ATP (data not shown). Rate constants obtained from time traces were plotted against tRNAGln concentration to obtain kon of 1.2 × 108 M−1sec−1. This rate constant is close to the diffusion limit, as expected for tight substrate binding. We then calculated koff of 5.2 sec−1 from kon and Kd values, because a direct estimate of koff from the plot of kobs versus enzyme concentration is subject to error (Figs. 1b and 3b). This approximation is justified, because the equilibrium constant, K1/2 obtained from single-turnover kinetics (Fig. 2c) is equivalent to Km obtained in steady-state reactions, and is also comparable to Kd measured independently.31,35 The absence of evidence for lag kinetics in any of the reaction progress curves (Fig. 2b) further suggests that K1/2 of 43 ± 18 nM indeed represents Kd.

Fig. 3.

Binding of tRNAGln to GluRSND. (a) Time course monitoring the decrease in intrinsic Trp fluorescence upon addition of varying concentrations of tRNAGln using a stopped-flow instrument. A sample trace at 500 nM GluRSND and 500 nM tRNAGln is shown, from which kobs of 50 sec−1 was derived. (b) Plot of observed association constants against concentration of tRNAGln, from which kon of 1.2 × 108 M−1sec−1 is derived. Equations to fit the raw data and to derive elementary rate constants are provided in Materials and Methods (equations (1) and (2), respectively).

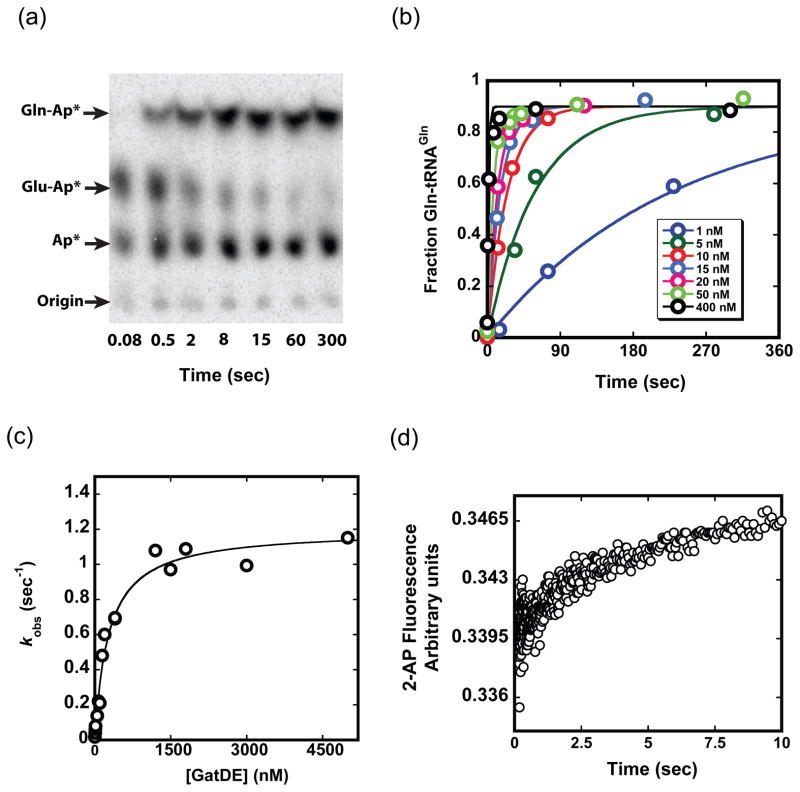

Binding of GatDE to Glu-tRNAGln is rate-limiting for kcat/Km

We next monitored the conversion of Glu-tRNAGln to Gln-tRNAGln by GatDE, at saturating ATP and asparagine levels (10 mM and 9.1 mM, respectively; Figs. 4a and b). The Glu-tRNAGln substrate was obtained from preparative reactions with GluRSND, and then purified for these experiments. Initial velocities monitored under steady state conditions with varying Glu-tRNAGln concentration yields kcat of 1.47 sec−1, Km of 4.38 μM, and kcat/Km of 3.4 × 105 M−1sec−1, similar to an earlier report.37 Under single turnover conditions, saturation of the rate for conversion of Glu-tRNAGln to Gln-tRNAGln occurred at about 1 μM GatDE (Figs. 4b and c), giving kmax of 1.2 sec−1. This rate was unaffected by inclusion of GluRSND in the reactions at equimolar concentration with GatDE.31 Because kmax is equivalent to kcat obtained in steady-state reactions, it appears that the rate-limiting step is formation of Gln-tRNAGln, and not its dissociation from GatDE. Consistent with this finding, rates measured under pre-steady state conditions allowing observation of both the first and subsequent turnovers showed no burst of product formation (data not shown). The kmax for the GatDE reaction is 10-fold higher than kmax for the GluRSND reaction (Fig. 1), implying efficient conversion of Glu-tRNAGln to Gln-tRNAGln upon GatDE binding.

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of the GatDE reaction. (a) Timecourse of a GatDE reaction showing TLC separation of Gln-tRNAGln from Glu-tRNAGln and tRNAGln. (b) Time traces for the formation of Gln-tRNAGln from purified Glu-tRNAGln under single turnover conditions. Concentrations are less than 1 nM for Glu-tRNAGln and as depicted for GatDE. Curves are fit to F = Fmax(1−e−kt), where F is the fraction Gln-tRNAGln formed, Fmax is the maximum (plateau) value of F, k is the rate constant (sec−1) and t is time (sec). (c) Plot of the GatDE concentration dependence of kobs obtained from (b); from which we derive kmax of 1.2 ± 0.04 sec−1. The curve is fit to: kobs = kobs,max[GatDE]/(K1/2 + [GatDE]). (d) Increase in fluorescence of 2-AP labeled tRNA (average of three traces) upon binding of 2.5 μM GatDE giving kon of 2.6 ± 0.11 × 105 M−1sec−1. The equation used to fit the raw fluorescence data is provided in Materials and Methods (equation 3).

To determine the rate-limiting step for the GatDE reaction, we first noted that Km derived from steady-state measurements is about 10-fold higher than Kd of 690 nM obtained from a filter binding experiment (Fig. S1a). In addition, the rate constant for Glu-tRNAGln dissociation from GatDE determined from filter binding experiments is about 10-fold lower than the roughly estimated kmax of 1.2 sec−1 obtained by hand sampling of this fast event (Fig. S1b). These data strongly suggested that binding could be rate-limiting for kcat/Km, - a case of Briggs-Haldane kinetics in which almost every Glu-tRNAGln binding event results in Gln-tRNAGln formation, since substrate dissociation is slow relative to Gln-tRNAGln formation (Fig. 1b). We therefore directly measured the rate constant for association by using 5′-2-aminopurine labeled Glu-tRNAGln, which shows fluorescence enhancement upon binding of GatDE (Fig. S2). At 2.5 μM GatDE, the fluorescence change fit well to a single exponential function with a rate constant of 0.64 sec−1 (Fig. 4d). The second order rate constant for binding, 2.6 ± 0.1 × 105 M−1sec−1, is identical within error to the value of kcat/Km, and koff calculated from Kd and this kon measurement is also equivalent to the experimental measurement (Fig. S1) – validating this estimate of 1.2 sec−1 for dissociation. Thus, association of Glu-tRNAGln is rate-determining for kcat/Km in the GatDE-mediated formation of Gln-tRNAGln.

Two-step dissociative mechanism

The steady-state and elementary rate constants for the separate GluRSND and GatDE reactions (Fig. 1b) allow prediction of reaction progress curve profiles by kinetic modeling, for two extreme scenarios: (i) strict channeling of Glu-tRNAGln between GluRSND and GatDE in a “transamidosome” complex as previously proposed;31 (ii) a distributive two-step pathway in which Glu-tRNAGln is released from GluRSND into solution before binding to GatDE. In the first model, where Gln-tRNAGln is only formed by channeling (Figs. S3a, S4), free Glu-tRNAGln does not associate with this particle and is converted to product only in the presence of complexed GatDE. Because kmax for GatDE is 10-fold faster than for GluRSND (Fig. 1b), direct channeling implies that Gln-tRNAGln formation is primarily limited by formation of Glu-tRNAGln. With fast transfer of Glu-tRNAGln between GluRSND and GatDE, a channeling model predicts rapid Gln-tRNAGln formation, without a time lag and with no accumulation of Glu-tRNAGln.34 In contrast, a two-step sequential model (Figs. S3b, S5a) predicts that Gln-tRNAGln formation is limited at least in part by the binding of Glu-tRNAGln to GatDE. This would result in accumulation of Glu-tRNAGln in amounts decreasing with increasing concentration of GatDE. A lag in Gln-tRNAGln formation is also predicted, even at high concentrations of GatDE. Finally, we also model the consequences of “relaxed” or partial channeling, in which only specified fractions of the Glu-tRNAGln formed in the first reaction are channeled (Figs. S5b–S5f).

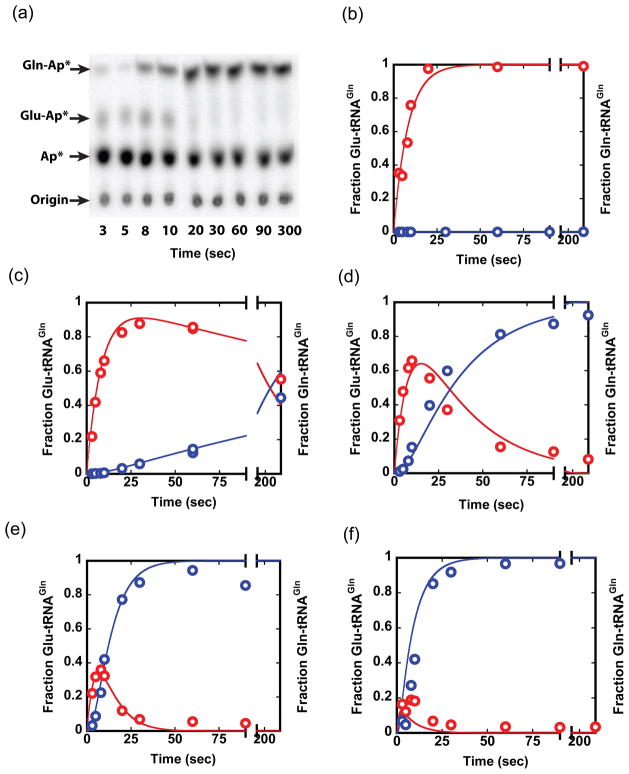

The two limiting kinetic models make distinct predictions regarding formation and reaction of the Glu-tRNAGln intermediate. To test these models experimentally, we measured Gln-tRNAGln formation in complete reactions containing both enzymes, tRNAGln, 10 mM ATP, 50 mM glutamate, and 9.1 mM asparagine as amide donor (Fig. 5). The data shows transient accumulation of Glu-tRNAGln at all concentrations of GatDE tested, from 10 nM to 6 μM, in the presence of saturating concentration of 600 nM GluRSND (Figs. 5c–5f). The amplitude of Glu-tRNAGln formation is inversely proportional to the GatDE concentration, as predicted in a distributive model. Lags in the formation of Gln-tRNAGln were also observed, with durations varying inversely with GatDE concentration. Comparison of the experimental product formation data with the kinetic models demonstrates that the data are consistent only with a two-step mechanism in which Glu-tRNAGln must dissociate and rebind to GatDE (Figs. 5c–5f). In contrast, models invoking strict or partial channeling made predictions in sharp disagreement with the observed data (Figs. S4 and S5). Since all of the parameters (unimolecular and bimolecular rate constants) were fixed in the kinetic modeling, this high level of correlation between the observed data and our model indicates credibility of the two-step model. Even at 30 μM GatDE, persistent accumulation of about 10% Glu-tRNAGln is observed (data not shown), as predicted by the dissociative kinetic model at and beyond 30 μM GatDE. Thus, the dissociative model predominates at least up to 30 μM GatDE. From the partial channeling kinetic models, we estimate that at least 80–90% of the Glu-tRNAGln must dissociate and then rebind to GatDE.

Fig. 5.

Combined GluRSND and GatDE reactions. (a) TLC plate showing transient accumulation of the Glu-tRNAGln intermediate during conversion of tRNAGln to Gln-tRNAGln in the presence of both GluRSND (600 nM) and GatDE (600 nM). Plots of normalized data and kinetic simulation traces (not fits to data) for a two-step dissociative mechanism at 600 nM GluRSND and GatDE at 0 nM (a), 10 nM (b), 100 nM (c), 600 nM (d) and 6 μM (e). tRNAGln in all the reactions < 1 nM. The panels show that, at all tested concentrations of GatDE, a distributive model fits the data well. Goodness of fit values (R2) from the nonlinear regression were computed separately using GraphPad software; for formation and reaction of Glu-tRNAGln these values range from 0.91 to 0.97. See Supplementary Figs. S3–S5 for details of kinetic simulations and evidence that a channeling model does not fit the data.

Although the lack of substrate channeling does not exclude formation of a GluRSND-GatDE complex, this finding does call the biological rationale for the proposed “transamidosome” into question. Therefore, although GluRSND-GatDE complex formation was previously investigated by several techniques,31 we reexamined this question using enzyme preparations produced in our laboratory. Using the identical expression construct and general purification procedure for cleavage and purification of the intein-ligated GluRSND enzyme, we found that exhaustive wash steps after chitin column loading and the use of fresh DTT for intein mediated cleavage, are required to remove a persisting 17 kD contaminant (Fig. S6 and Supplemental Methods). Examination of GluRSND-GatDE complex formation by native gel electrophoresis on both agarose and polyacrylamide gels revealed that only contaminated GluRSND preparations bind to GatDE; further, the isolated contaminant fractions are shown to possess the GatDE binding activity (Fig. S6). Gel filtration HPLC coupled to static light scattering, using the highly purified GluRSND fraction at concentrations in the 10 μM range, similarly failed to reveal formation of GatDE-GluRSND binary complexes. Because evidence of GluRSND homogeneity was not presented in the earlier report, it is not possible to be definitive with respect to the origin of the discrepancy.31 However, based on our findings with the same expression construct, it is reasonable to suggest that the previously observed formation of a M. thermautotrophicus GatDE-GluRSND complex also is due to the contaminating protein, and that a GluRSND-GatDE complex does not form.

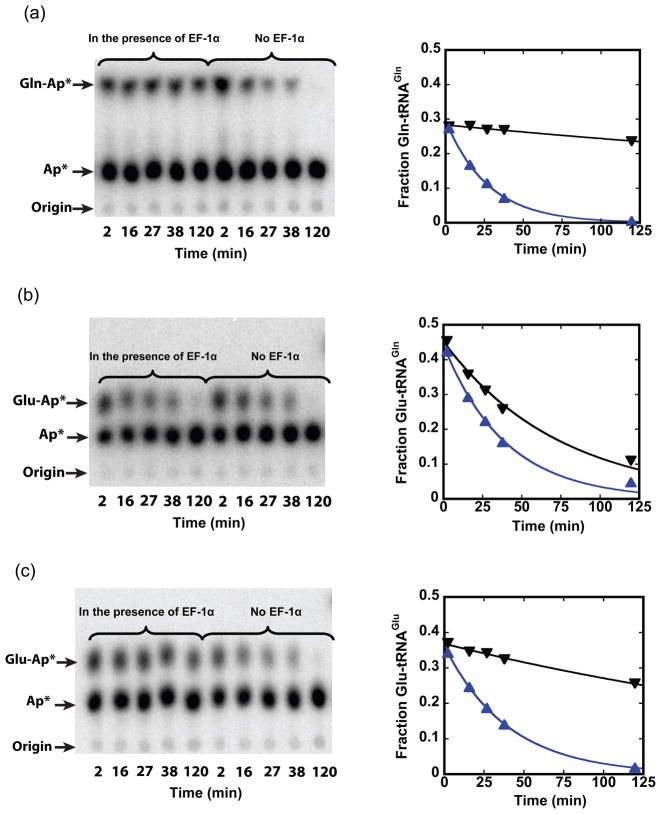

Archaeal EF-1α discriminates against Glu-tRNAGln

Because our findings contradict both binary complex (“transamidosome”) formation and the previous proposal for direct channeling of Glu-tRNAGln,31 we considered alternative mechanisms that might exist in Archaea to avoid misincorporation of Glu at glutamine codons. It is known that the bacterial elongation factor EF-Tu is able to strongly discriminate against Glu-tRNAGln.38,39 Archaeal EF-1α proteins are 35% identical in sequence with bacterial EF-Tu (Fig. S7), suggesting that a similar mechanism may function in Archaea. We cloned EF-1α from M. thermautotrophicus genomic DNA, purified the (His)6-affinity-tagged protein to homogeneity, and measured binding to Gln-tRNAGln, Glu-tRNAGlu and misacylated Glu-tRNAGln by protection of these species from spontaneous deacylation. In the absence of EF-1α, the rate constant for deacylation is very similar for all three aminoacyl-tRNAs, as expected (Fig. 6). In the presence of 2.2 μM activated EF-1α, there is 24-fold protection of Gln-tRNAGln and 8-fold protection of Glu-tRNAGlu. In contrast, Glu-tRNAGln was poorly protected from deacylation at the same concentration of EF-1α, suggesting weaker binding.

Fig. 6.

Discrimination against Glu-tRNAGln by archaeal EF-1α. TLC images showing spots corresponding to acylated (Gln-Ap*) and deacylated (Ap*) tRNAs (left panels) were quantified to give the fraction of (a) Gln-tRNAGln, (b) Glu-tRNAGln and (c) Glu-tRNAGlu in the presence of 2.2 μM activated EF-1α (inverted triangles) or in the presence of activated EF-1α following proteinase K incubation for 10 minutes (triangles). When EF-1α is removed by proteolysis, the rate constants for spontaneous deacylation are 0.036 min−1, 0.025 min−1, and 0.025 min−1 for the three aminoacyl-tRNAs, respectively (blue traces). In the presence of activated EF-1α, the rate constants are: 0.0015 min−1 for Gln-tRNAGln, 0.013 min−1 for Glu-tRNAGln, and 0.003 min−1 for Glu-tRNAGlu, respectively (black traces).

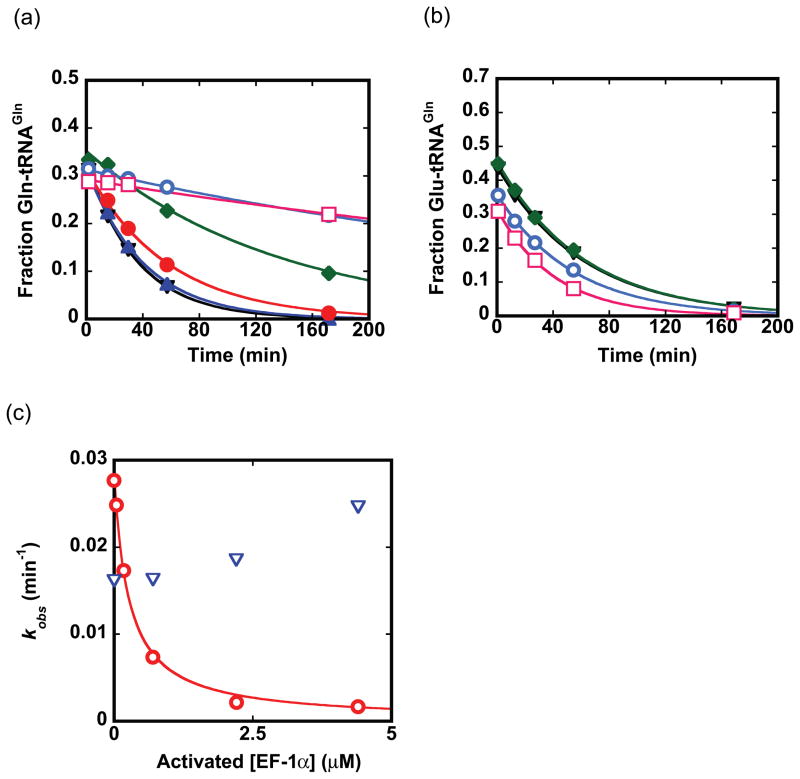

To provide a quantitative estimate of the difference in EF-1α binding affinity to misacylated Glu-tRNAGln versus cognate Gln-tRNAGln, we measured the rate constant for deacylation at varying concentrations of EF-1α (Fig. 7). Gln-tRNAGln showed both increased protection and a substantial decrease in the rate constant for deacylation with increased levels of EF-1α, allowing derivation of K1/2, which is analogous to the binding affinity (K1/2 of 0.29 ± 0.03 μM). No protection of Glu-tRNAGln even at an activated EF-1α concentration of 4.4 μM was observed; from these data, we deduce that Glu-tRNAGln binds at least 40-fold weaker than Gln-tRNAGln. The discrimination may arise because EF-1α binds Gln-tRNAGln with a faster association rate, a slower dissociation rate, or both, compared with its capacity to bind Glu-tRNAGln.

Fig. 7.

Binding affinity of EF-1α to aminoacyl-tRNAs. Decreases in the fraction of Gln-tRNAGln (a) and Glu-tRNAGln (b) present over time in the presence of different concentrations of EF-1α at 0 μM (black inverted triangles), 0.044 μM (blue filled triangles), 0.17 μM (red filled circles), 0.7 μM (green filled diamonds), 2.2 μM (cyan circles), and 4.4 μM (pink squares). Each timecourse is fit to an exponential function to derive kobs. (c) Rate constants for protection of spontaneous deacylation in the presence of EF-1α obtained from panels (a) and (b) are replotted and fit to a hyperbolic binding curve to derive the Kd for EF-1α binding to Gln-tRNAGln (0.29 ± 0.03 μM; red trace). No significant correlation of the rate constant for deacylation of Glu-tRNAGln, with increasing EF-1α concentration, could be made (blue inverted triangles indicate the data in this case).

Further selectivity against incorporation of glutamate at glutamine codons arises from ATP hydrolysis by GatDE, which provides a strongly favorable thermodynamic driving force in the direction of Gln-tRNAGln formation. At a kinetic level, GatDE and EF-1α function independently, since inclusion of EF-1α at equimolar concentrations in GatDE single-turnover reactions and in combined GluRSND-GatDE reactions is without effect on kobs (data not shown). However, these reactions are thermodynamically coupled, so that selective EF-1α binding of Gln-tRNAGln will clearly provide a further driving force shifting the equilibrium on GatDE toward product formation. The intracellular level of EF-Tu in bacteria is 100 μM;56 comparably high concentrations of EF-1α in M. thermautotrophicus, if present, would strongly favor this mechanism. We suggest that these considerations are sufficient to account for specificity in glutamine incorporation exceeding the estimated error rate of 10−4 in protein synthesis,40 without the need to invoke either channeling or “transamidosome” formation. Of course, additional capacity for discrimination against noncognate Glu-tRNAGln may also be available during decoding or post-peptidyl transfer on the ribosome.41,42

All canonical, monomeric class I aaRS so far studied exhibit burst kinetics, while the absence of a burst is instead characteristic of class II aaRS.43 In several class I bacterial aaRS, aminoacylation rates are also enhanced by EF-Tu binding, and observed ternary complexes composed of both proteins with aminoacylated tRNA are consistent with the notion of direct transfer of aminoacylated tRNA. In contrast, class II aaRS are not stimulated by EF-Tu.43 To test whether the archaeal EF-1α influences the reaction of a nondiscriminating aaRS catalyzing misacylated tRNA formation, we examined its influence on GluRSND kinetics under both steady-state and single-turnover conditions. We found that the inclusion of EF-1α in excess of GluRSND concentration had no effect on the rate of reaction in either case (data not shown). Thus, the previously observed correlation of elongation factor rate enhancement with slow product release in aaRS is maintained. M. thermautotrophicus GluRSND remains unusual, however, as it represents a rare example of a class I aaRS that is not rate-limited by the release of aminoacylated tRNA (Fig. 2), thus violating the class-specific rule.43 The only other known exception is the dimeric tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase.58

Discussion

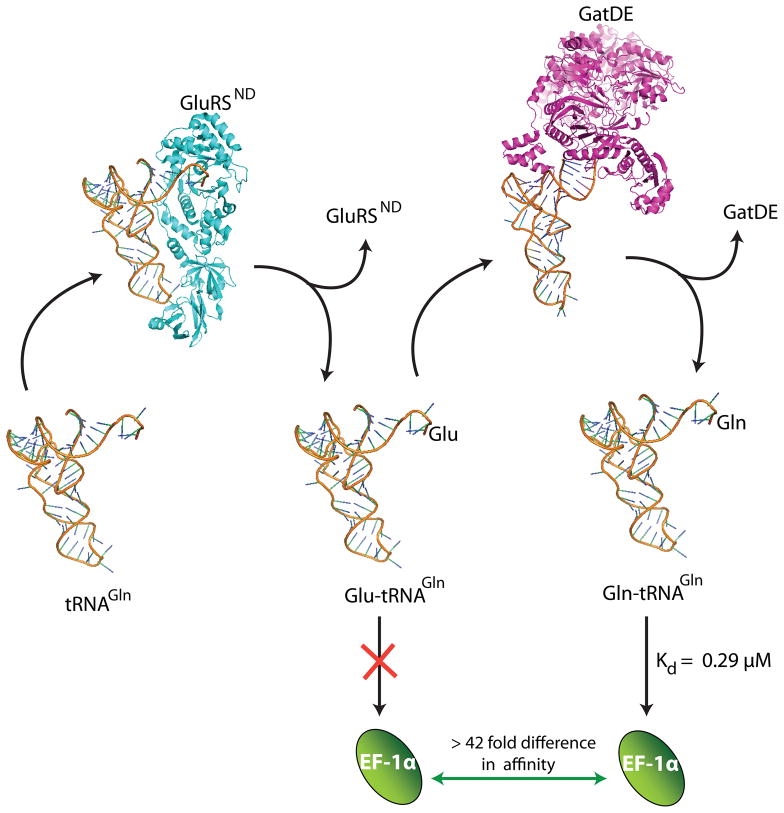

We have applied a general methodology based on pre-steady state kinetics to probe substrate channeling in an RNA-based system, following the approach developed to study channeling in bifunctional metabolic enzymes.33,34 Previous experimental and computer modeling studies of the GluRSND-GatDE pathway concluded that a protein-protein complex forms between GluRSND and GatDE, and that its formation is essential to sequestering Glu-tRNAGln via a channeling mechanism.30,31 The pre-steady state kinetic data presented here refutes these notions by demonstrating that the two enzymes function independently: the Glu-tRNAGln intermediate dissociates from GluRSND prior to rebinding GatDE (Figs. 5, 8, S3–S5). We also demonstrate that the GluRSND-GatDE binary complex previously reported may depend on the presence of a contaminating protein, which artefactually binds GatDE (Fig. S6). We cannot detect formation of a protein-protein complex when highly purified materials are used at concentrations up to 10 μM. Clearly, the independent, distributive function of GluRSND and GatDE (Fig. 8) is consistent with the absence of a binary complex.

Fig. 8.

Model for two-step synthesis of Gln-tRNAGln without channeling in Archaea. In this model independent, distributive function of GluRSND and GatDE together with exclusion of Glu-tRNAGln binding by elongation factor suffices for selective glutamine incorporation in M. thermautotrophicus.

The lack of influence of either GluRSND or GatDE on the independent reaction of the partner enzyme was noticed previously,31 but the notion of an archaeal-specific transamidosome that functions to sequester Glu-tRNAGln was nonetheless promulgated. Such a binary transamidosome confined to the protein-protein complex alone had been distinguished from proposed bacterial transamidosomes consisting of ternary GatCAB/GluRSND/tRNAGln or GatCAB/AspRSND/tRNAAsn complexes,28–30 where individual enzyme activities are improved upon complex formation, and where channeling was also postulated. The existence of GatCAB-based transamidosomes is clearly well-founded based on the detection of ternary complexes in crystals and in solution. However, the kinetic analyses of the GatCAB systems did not explicitly monitor the misacylated tRNA intermediates and so do not provide evidence for channeling.28–30 Channeling is certainly plausible in each case, perhaps especially so for the bacterial AspRSND-GatCAB pathway where complex formation strongly stimulates individual enzyme activities.28 However, a clear demonstration requires transient kinetic measurements. Channeling was also proposed for the two-step pathway to Cys-tRNACys formation in methanogens,44 in which phosphoseryl-tRNA synthetase (SepRS) synthesizes a phosphoseryl-tRNACys misacylated intermediate that is then converted to Cys-tRNACys by the subsequent enzyme SepCysS. In this case as well, however, a definitive analysis is lacking.45

Our results demonstrate that substrate channeling is not required for efficient and precise coding in two-step aminoacylation pathways. The robust mechanisms to prevent misincorporation without channeling in this case include unidirectional conversion of the misacylated intermediate in the ATP-driven GatDE reaction, and at least 40-fold discrimination against Glu-tRNAGln by EF-1α (Fig. 1b and 8). An interesting feature of the pathway is the relatively slow and rate-limiting binding of the misacylated tRNA intermediate by GatDE. While this may appear inefficient, it is known that slow, rate-limiting binding can improve specificity by discriminating against noncognate substrates using a kinetic induced-fit mechanism.46 Moreover, the finding that GatDE follows Briggs-Haldane kinetics demonstrates an efficient mechanism that precludes dissociation of misacylated tRNA once bound (Fig. 4). Selectivity for Glu-tRNAGln is achieved by close monitoring of the tRNA D-loop by the GatDE tail domain, precluding a productive interaction with the larger D-loop of tRNAGlu.27 We speculate that tRNAGlu may be rejected by GatDE at the level of complex formation because of slow association or induced-fit, or because it may readily dissociate upon binding. Further detailed kinetic measurements will be required to address these hypotheses.

It is difficult to be definitive in extrapolating these in vitro data to the in vivo environment of the archaeal cell, because the concentrations of the relevant proteins have not been directly measured. However, in Escherichia coli cells, the concentration of each tRNA synthetase is approximately 1 μM,47 and the levels of individual tRNA isoacceptor families are in the range 2.5 – 10 μM.48 The experimentally derived estimate of tRNA synthetase concentrations made in E. coli is consistent with the levels of prolyl-tRNA synthetase that could be purified from native Methanocaldococcus jannaschii cells,49 suggesting that the abundance of these enzymes may be roughly equivalent in Bacteria and Archaea. If levels of GluRSND, GatDE, and tRNAGln in M. thermautotrophicus cells are in these ranges, then in vivo channeling of Glu-tRNAGln is unlikely since our findings indicate little to no channeling at GatDE concentrations up to 30 μM. Further, we note that in the mammalian cytoplasm where channeling has been demonstrated in vivo, the supramolecular architecture of the translation system depends on actin filaments.50 In Archaea, actin homologs have been found in some Crenarchaeotes and in the Korachaeota,51 but not among the methanogens, which belong to the Euryarchaeota. An analog to actin (MreB) that performs a cytoskeletal role is found in Bacteria,52 but no in vivo experiments to examine channeling in bacterial translation have been reported. Thus, the popular notion that channeling is prevalent in the early steps of translation in Bacteria and Archaea still lacks a strong experimental foundation. In this regard, direct monitoring of proposed channeled intermediates by transient kinetics, as we have demonstrated here, offers the most definitive available in vitro test for comparison with in vivo findings.

Materials and Methods

Overexpression and purification of GluRSND and GatDE

The purification of M. thermautotrophicus GluRSND followed the general procedure previously reported.24,25,31,35 pLysS Rosetta cells were grown at 37°C to A600 of 0.8, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, and allowed to grow overnight at 25°C. The cells from 1 liter of saturated culture were centrifuged and resuspended in 35 mL of lysis buffer containing 20 mM sodium Hepes (pH 8.5) and 500 mM NaCl, followed by addition of 150 μg DNAse I, 50 mg lysozyme, and 1 pellet protease inhibitor (Complete Mini, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets – Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Germany). The cells were sonicated for 5 min with an alternating 2 sec pulse on and pulse off mode using a Branson 450 digital sonicator (Danbury, CT). The cell-free lysate was then centrifuged at 15,000 × rpm for 45 min and the supernatant applied to a 5–10 ml. Chitin affinity matrix (New England Biolabs) pre-equilibrated in lysis buffer. To obtain highly purified enzyme (Fig. S6), the column was washed extensively with five or more column volumes of lysis buffer. The column was then quickly flushed with cleavage buffer containing 500 mM NaCl and 50 mM DTT, using freshly made DTT stock solutions, and the resin then incubated for 8–12 hours to allow cleavage of chitin bound CBP-intein from GluRSND. Cleaved enzyme was then eluted with addition of more cleavage buffer. The recovered material was dialyzed against and stored in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 50% glycerol. Yield of purified enzyme from one liter of cell culture is about 2 mg. The purity is estimated to be greater than 95% (Fig. S6). See Supplemental Material for further details.

The pET20b-MtGatDE vector for GatDE expression was transformed into pLysS Rosetta cells, and His6-tagged-GatDE was purified as described previously25. The cells were grown at 37°C to OD600 of 0.8, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 15°C and allowed to grow overnight. Two-liter overnight cultures were pooled, centrifuged and cell pellets were resuspended in 25 mL lysis buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole. 150 μg of DNase I, 50 mg of lysozyme, and 1 pellet of protease inhibitor (Complete Mini, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets, Roche Diagnostics, GmbH) were then added. The cell mixture was sonicated for 5 min at an alternating 2 sec pulse on and pulse off mode using a Branson (Danbury, CT) 450 digital sonicator. The cell-free lysate was then centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 45 min and the supernatant applied to a pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA His-bind resin (Qiagen) column. The column was washed with a buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole and dialyzed against 25 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.2), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 50% glycerol. The yield of purified enzyme from 1 L of cell culture is approximately 2 mg. The purity is over 95% as estimated by SDS–PAGE.

In vitro synthesis of tRNAGln and tRNAGlu transcripts

M. thermautotrophicus tRNA2Gln,27 and tRNAGlu were prepared by in vitro transcription as described previously.35 DNA templates for tRNAGlu were synthesized from complementary oligodeoxynucleotides with an overlap region. The forward and reverse oligonucleotides used are: AATTCCTGCAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGCTCCGGTAGTGTAGTCCGGCCAATCATTT and: mUmGGTGCTCCGGCCGGGATTTGAACCCGAGTCTTCGGCTCGAAAGGCCGAAATGATTGG. The underlined sequence represents the T7 promoter. For synthesis of both tRNAGlu and tRNAGln, 5 mL transcription reactions were performed by incubating 5 μg/mL DNA template, 40 mM DTT, 1mM of each of the four NTPs, 400 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 250 mM MgCl22+, 20 μM spermidine, 0.1% Triton x-100 and 120 μg/mL Del(172–173) variant of T7 RNA polymerase,57 for 4 hr at 37°C.35 The reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 mL of 0.5 mM EDTA; the tRNA was then ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 1 mL water. 40 μL of DNAse was added and the solution incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. The transcript was purified on a 5 mL DEAE column (DE-52; Whatman). The transcript was eluted, ethanol precipitated, resuspended in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA (TE), and stored at −20 °C.

3′-labeling of tRNA with α-[32P] ATP

1–2 μM of tRNAGln or tRNAGlu stored in TE buffer was heated to 80°C in the absence of Mg2+, MgCl2 solution at 80°C was added to a final concentration of 6.25 mM, and the RNA allowed to slow-cool to room temperature. Labeling was performed using tRNA nucleotidyltransferase in the presence of α-[32P] ATP as described previously.32, 53, 54

Aminoacylation and amidotransferase kinetics

All reactions were performed in 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl22+ and 5 mM DTT unless otherwise specified. Fast reactions were measured using a Kintek RQF3 rapid chemical quench instrument. All reactions were quenched for 8–10 min in either 400 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2) containing 0.01 mg/mL P1 nuclease (Fluka), or in 0.1% SDS followed by addition of P1 nuclease to 0.1 mg/mL. Aliquots were spotted on pre-washed PEI-cellulose TLC plates (Sigma) and developed in a solution containing 100 mM ammonium acetate, 5% (v/v) acetic acid. The plates were dried and quantitated by phosphorimaging. [32P]-labeled AMP, Gln-AMP and Glu-AMP migrate at clearly distinguishable positions. Quantitation was done with Imagequant (version 5.2) and Kaleidagraph (version 4.03).

Purification of α-[32P] labeled Glu-tRNAGln and Gln-tRNAGln

Purified 3′-[32P] labeled Glu-tRNAGln and Gln-tRNAGln were obtained by aminoacylation under conditions similar to that described in the previous section, except that the Hepes buffer concentration was reduced to 5 mM to facilitate buffer exchange. The aminoacylation reaction was performed with 100 nM GluRSND alone or with a mixture of 100 nM GluRSND and 100 nM GatDE for 20 minutes. Immediately following the reaction, the pH was lowered by addition of 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2), and the aminoacylated tRNAs were acid phenol-chloroform extracted and buffer exchanged four times with 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 1 mM EDTA (SE) buffer using Amicon ultra-0.5 filters (Millipore). The aminoacylation levels of [32P]-Glu-tRNAGln and [32P]-Gln-tRNAGln were quantitated by complete digestion of the tRNAs with P1 nuclease followed by TLC analysis in the same solvent system used to monitor aminoacylation and amidotransferase timecourses (see above). The aminoacyl-tRNAs were stored in SE buffer at −20°C and used within 2 days.

Fluorescence stopped-flow measurements

Binding of tRNAGln to GluRSND was monitored by stopped-flow fluorimetry using the intrinsic Trp fluorescence signal, while binding of Glu-tRNAGln to GatDE utilized 2-aminopurine (2AP) attached to the tRNA 5′-end. For 5′-2AP labeling, tRNAGln was misacylated by GluRSND to form Glu-tRNAGln at levels corresponding to 60% of the RNA, and this product purified by acid phenol-chloroform extraction and exchange into SE buffer (see section above on purification of α-[32P] labeled aminoacyl-tRNAs). Aminoacylation protects the 3′end of the tRNA in the 5′-labeling reaction. For labeling, Glu-tRNAGln was incubated with 1 mM 2-AP triphosphate (Biolog lifescience, Germany), 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.0) and 10 U/μL T4 ligase I at 37°C for 5 min.55 This was followed immediately by addition of sodium acetate (pH 5.2) to a final concentration of 167 mM, and purification by acid-phenol chloroform extraction and exchange into SE buffer. 2AP-labeled Glu-tRNAGln is stored at −20°C and used within 2 days.

Rapid binding kinetics were measured using a stopped-flow fluorescence instrument (Applied Photophysics SX.18MV). For GluRSND, the change in intrinsic Trp fluorescence was monitored upon binding of tRNAGln. The excitation wavelength was 285 nm and emission was monitored through a 305 nm cut-off filter. Experiments were initiated by mixing tRNA from one syringe with enzyme from the second syringe. Fluorescence traces were fit to the equation:

| (1) |

where F is fluorescence in arbitrary units, Fmax is maximum fluorescence amplitude, F0 is the initial fluorescence, kobs is the rate constant in units of sec−1, and t is time in units of seconds. A control experiment in which enzyme was mixed with buffer alone, rather than tRNA, gave no change in the fluorescence.

At least four traces were obtained for every concentration of tRNAGln and the average kobs is reported. kon and koff were obtained by fitting to the equation:36

| (2) |

The binding of Glu-tRNAGln to GatDE was monitored with 5′ 2-AP labeled substrate. The excitation wavelength used was 307 nm, and increase in the fluorescence of 2-AP Glu-tRNAGln upon rapid mixing with GatDE was monitored through a 320 nm cut-off filter. Three traces were averaged to obtain kobs. kobs was divided by the concentration of GatDE used, 2.5 μM, to derive the kon value. Fluorescence traces were fit to the equation:

| (3) |

EF-1α protection assay

EF-1α was cloned, overexpressed, and purified as described in the Supplementary Material. The purified EF-1α was activated (see below) prior to performing protection assays. To perform protection assays, purified [32P]Gln-tRNAGln, [32P]Glu-tRNAGln or [32P]Glu-tRNAGlu were added to a 20μL reaction containing activated EF-1α or a buffer control, in the presence of 100 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 6 mM phosphoenol pyruvate, 6 μg/mL pyruvate kinase, 100 mM ammonium chloride, and 2 mM MgCl2. The fraction of deacylated tRNA at 37°C over time was measured by quenching 3 μL aliquots from the 20 μL reaction in 15 μl quench solution containing 5 μl of 400 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 10 μl phenol-chloroform. After vigorous mixing, the tRNA was extracted, and P1 nuclease was added at 75 μg/ml to the recovered tRNA, followed by separation of substrate and products by TLC as described above. Rate constants for protection of deacylation, as a function of EF-1α concentration, were fit to the following equation:59

| (4) |

where kunprotected is the observed rate constant for deacylation in the absence of EF-1α, and K1/2 is the affinity of EF-1α to Gln-tRNAGln.

EF-1α activation

EF-1α was activated by incubating in 100 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 6 mM phosphoenol pyruvate, 6 μg/mL pyruvate kinase, 100 mM ammonium chloride, and 2 mM Mg2+-GTP at 37°C for over 24 hours. The fraction of active EF-1α was determined by incubating 50 μM EF-1α with different concentrations of [32P]-α labeled GTP. The mixture was then filtered through a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were immediately washed with 100 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT wash buffer, dried, and subject to phosphorimaging analysis. The amount of GTP bound by EF-1α reflects the fraction of EF-1α that is active. At different concentrations of GTP and EF-1α, the same fraction was active, i.e., about 8.85%, and the term “activated” EF-1α reflects this correction.

Kinetic simulations

All simulations were performed using Berkeley Madonna, Ver 8.3.14 (Macey and Oster, UC-Berkeley) by Runge-Kutta 4 integration method. The chemical reaction module of Madonna was used for constructing initial models. The reactant and product concentrations as shown for each model in Figure 3 were directly input in the “Reactants” and “Products” boxes. Both forward and reverse rate constants at each step were assigned. Reverse rate constants for catalytic steps (tRNA aminoacylation and ATP-dependent amidotransferase) were presumed to be very slow and were assigned values of zero. First-order and second-order rate constants were directly input keeping the same units for consistency (sec−1 for 1st order and M−1sec−1 for 2nd order). Initial GatDE concentration was input at 600 nM, but was varied using the Define slider option to 0 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 600 nM and 6 μM. GluRSND and tRNA concentrations were fixed at 600 nM and 100 pM, respectively; varying the concentration of tRNA did not affect the simulated plot as long as the tRNA concentration was maintained below the enzyme concentration. All parameters (first and second order rate constants) were fixed and not allowed to change. For the two step dissociative mechanism (Figure S4b), the fraction of Glu-tRNAGln and Gln-tRNAGln were defined in the equations window as Fraction P = P+E2P/(S+ES+P+E2P+E2P2+P2) and Fraction P2 = P2/(S+ES+EP+P+E2P+E2P2+P2), where S, ES, P, E2P, P2 and E2P2 represent tRNAGln, GluRSND:tRNAGln, Glu-tRNAGln, GatDE:Glu-tRNAGln, Gln-tRNAGln and GatDE:Gln-tRNAGln, respectively. For purposes of simplicity, the product dissociation steps are not shown in Fig. S3. Since product dissociation was found to be faster than reaction for both GluRSND and GatDE (see text), any rate constant greater than 1 sec−1 for Glu-tRNAGln dissociation from GluRSND and greater than 10 sec−1 for Gln-tRNAGln dissociation from GatDE did not affect the simulated plots. We therefore fixed these rate constants at 50 sec−1. The definition of fractions P and P2 were appropriately modified for the channeled and partially channeled pathways.

Estimate of errors

Many experiments were performed with two to three different preparations of GluRSND and/or GatDE, and consistency was verified. Most experiments were repeated in triplicate, and all reactions were performed at least twice; error estimates are provided as mean ± standard deviation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Distributive enzyme function maintains protein quality control in Archaea

Action of elongation factor contributes to stringency of glutamine coding in Archaea

Explicit monitoring of metabolic intermediates is required to demonstrate channeling

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelley Sheppard and Dieter Söll for providing GluRSND and GatDE expression vectors, Michael Ibba for M. thermauotrophicus genomic DNA, Andrew Hadd for assistance with light scattering experiments, and Rick Russell for comments on kinetic simulations. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM63713).

Footnotes

Supplementary materials associated with this article can be found online at:

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson KS. Fundamental mechanisms of substrate channeling. Methods Enzymol. 1999;308:111–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)08008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang X, Holden HM, Raushel FM. Channeling of substrates and intermediates in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:149–180. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An S, Kumar R, Sheets ED, Benkovic SJ. Reversible compartmentalization of de novo purine biosynthetic complexes in living cells. Science. 2008;320:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1152241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenaz G, Genova ML. Structure and organization of mitochondrial respiratory complexes: a new understanding of an old subject. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:961–1008. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer FM, Gerwig J, Hammer E, Herzberg C, Commichau FM, Volker U, Stulke J. Physical interactions between tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes in Bacillus subtilis: evidence for a metabolon. Metab Eng. 2011;13:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhner S, van Noort V, Betts MJ, Leo-Macias A, Batisse C, Rode M, Yamada T, Maier T, Bader S, Beltran-Alvarez P, Castano-Diez D, Chen WH, Devos D, Guell M, Norambuena T, Racke I, Rybin V, Schmidt A, Yus E, Aebersold R, Herrmann R, Bottcher B, Frangakis AS, Russell RB, Serrano L, Bork P, Gavin AC. Proteome organization in a genome-reduced bacterium. Science. 2009;326:1235–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1176343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarassov K, Messier V, Landry CR, Radinovic S, Serna Molina MM, Shames I, Malitskaya Y, Vogel J, Bussey H, Michnick SW. An in vivo map of the yeast protein interactome. Science. 2008;320:1465–1470. doi: 10.1126/science.1153878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negrutskii BS, Deutscher MP. Channeling of aminoacyl-tRNA for protein synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4991–4995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stapulionis R, Deutscher MP. A channeled tRNA cycle during mammalian protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7158–7161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerjan P, Cerini C, Semeriva M, Mirande M. The multienzyme complex containing nine aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases is ubiquitous from Drosophila to mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1199:293–297. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyriacou SV, Deutscher MP. An important role for the multienzyme aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex in mammalian translation and cell growth. Mol Cell. 2008;29:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hausmann CD, Praetorius-Ibba M, Ibba M. An aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase:elongation factor complex for substrate channeling in archaeal translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6094–6102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Großhans H, Simos G, Hurt E. Review: transport of tRNA out of the nucleus-direct channeling to the ribosome? J Struct Biol. 2000;129:288–294. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandt F, Carlson LA, Hartl FU, Baumeister W, Grünewald K. The three-dimensional organization of polyribosomes in intact human cells. Mol Cell. 2010;39:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber D, Rajagopalan N, Preissler S, Rocco MA, Merz F, Kramer G, Bukau B. SecA interacts with ribosomes in order to facilitate posttranslational translocation in bacteria. Mol Cell. 2011;41:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godinic-Mikulcic V, Jaric J, Hausmann CD, Ibba M, Weygand-Durasevic I. An archaeal tRNA-synthetase complex that enhances aminoacylation under extreme conditions. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3396–3404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.168526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hausmann CD, Ibba M. Structural and functional mapping of the archaeal multi-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2178–2182. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karanasios E, Simader H, Panayotou G, Suck D, Simos G. Molecular determinants of the yeast Arc1p-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex assembly. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:1077–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curnow AW, Ibba M, Söll D. tRNA-dependent asparagine formation. Nature. 1996;382:589–590. doi: 10.1038/382589b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schon A, Kannangara CG, Gough S, Söll D. Protein biosynthesis in organelles requires misaminoacylation of tRNA. Nature. 1988;331:187–190. doi: 10.1038/331187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilcox M, Nirenberg M. Transfer RNA as a cofactor coupling amino acid synthesis with that of protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1968;61:229–236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fersht AR, Kaethner MM. Mechanism of aminoacylation of tRNA. Proof of the aminoacyl adenylate pathway for the isoleucyl- and tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases from Escherichia coli K12. Biochemistry. 1976;15:818–823. doi: 10.1021/bi00649a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curnow AW, Hong K, Yuan R, Kim S, Martins O, Winkler W, Henkin TM, Söll D. Glu-tRNAGln amidotransferase: a novel heterotrimeric enzyme required for correct decoding of glutamine codons during translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11819–11826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tumbula DL, Becker HD, Chang WZ, Söll D. Domain-specific recruitment of amide amino acids for protein synthesis. Nature. 2000;407:106–110. doi: 10.1038/35024120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng L, Sheppard K, Tumbula-Hansen D, Söll D. Gln-tRNAGln formation from Glu-tRNAGln requires cooperation of an asparaginase and a Glu-tRNAGln kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8150–8155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura A, Yao M, Chimnaronk S, Sakai N, Tanaka I. Ammonia channel couples glutaminase with transamidase reactions in GatCAB. Science. 2006;312:1954–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.1127156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oshikane H, Sheppard K, Fukai S, Nakamura Y, Ishitani R, Numata T, Sherrer RL, Feng L, Schmitt E, Panvert M, Blanquet S, Mechulam Y, Söll D, Nureki O. Structural basis of RNA-dependent recruitment of glutamine to the genetic code. Science. 2006;312:1950–1954. doi: 10.1126/science.1128470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailly M, Blaise M, Lorber B, Becker HD, Kern D. The transamidosome: a dynamic ribonucleoprotein particle dedicated to prokaryotic tRNA-dependent asparagine biosynthesis. Mol Cell. 2007;28:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blaise M, Bailly M, Frechin M, Behrens MA, Fischer F, Oliveira CL, Becker HD, Pedersen JS, Thirup S, Kern D. Crystal structure of a transfer-ribonucleoprotein particle that promotes asparagine formation. Embo J. 2010;29:3118–3129. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito T, Yokoyama S. Two enzymes bound to one transfer RNA assume alternative conformations for consecutive reactions. Nature. 2010;467:612–616. doi: 10.1038/nature09411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rampias T, Sheppard K, Söll D. The archaeal transamidosome for RNA-dependent glutamine biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5774–5783. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uter NT, Perona JJ. Long-range intramolecular signaling in a tRNA synthetase complex revealed by pre-steady-state kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14396–14401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404017101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang PH, Anderson KS. Substrate channeling and domain-domain interactions in bifunctional thymidylate synthase-dihydrofolate reductase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12195–12205. doi: 10.1021/bi9803168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bulock KG, Beardsley GP, Anderson KS. The kinetic mechanism of the human bifunctional enzyme ATIC (5-amino-4-imidazolecarboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase/inosine 5′-monophosphate cyclohydrolase). A surprising lack of substrate channeling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22168–22174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Hernandez A, Bhaskaran H, Hadd A, Perona JJ. Synthesis of Glu-tRNAGln by engineered and natural aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6727–6736. doi: 10.1021/bi100886z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong KW, Ibba M, Weygand-Durasevic I, Rogers MJ, Thomann HU, Söll D. Transfer RNA-dependent cognate amino acid recognition by an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Embo J. 1996;15:1983–1991. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheppard K, Sherrer RL, Söll D. Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus tRNAGln confines the amidotransferase GatCAB to asparaginyl-tRNAAsn formation. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asahara H, Uhlenbeck OC. The tRNA specificity of Thermus thermophilus EF-Tu. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3499–3504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052028599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LaRiviere FJ, Wolfson AD, Uhlenbeck OC. Uniform binding of aminoacyl-tRNAs to elongation factor Tu by thermodynamic compensation. Science. 2001;294:165–168. doi: 10.1126/science.1064242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling J, Reynolds N, Ibba M. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis and translational quality control. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:61–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrader JM, Chapman SJ, Uhlenbeck OC. Tuning the affinity of aminoacyl-tRNA to elongation factor Tu for optimal decoding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5215–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102128108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaher HS, Green R. Quality control by the ribosome following peptide bond formation. Nature. 2009;457:161–166. doi: 10.1038/nature07582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang CM, Perona JJ, Ryu K, Francklyn C, Hou YM. Distinct kinetic mechanisms of the two classes of Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauerwald A, Zhu W, Major TA, Roy H, Palioura S, Jahn D, Whitman WB, Yates JR, 3rd, Ibba M, Söll D. RNA-dependent cysteine biosynthesis in archaea. Science. 2005;307:1969–1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang CM, Liu C, Slater S, Hou YM. Aminoacylation of tRNA with phosphoserine for synthesis of cysteinyl-tRNACys. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:507–514. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karbstein K, Herschlag D. Extraordinarily slow binding of guanosine to the Tetrahymena group I ribozyme: implications for RNA preorganization and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2300–2305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252749799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jakubowski H, Goldman E. Quantities of individual aminoacyl-tRNA families and their turnover in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:769–776. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.769-776.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong H, Nilsson L, Kurland CG. Co-variation of tRNA abundance and codon usage in Escherichia coli at different growth rates. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:649–663. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipman RS, Sowers KR, Hou YM. Synthesis of cysteinyl-tRNA(Cys) by a genome that lacks the normal cysteine-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7792–7798. doi: 10.1021/bi0004955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stapulionis R, Kolli S, Deutscher MP. Efficient mammalian protein synthesis requires an intact F-actin system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24980–24986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ettema TJ, Lindas AC, Bernander R. An actin-based cytoskeleton in archaea. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:1052–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van den Ent F, Amos LA, Lowe J. Prokaryotic origin of the actin cytoskeleton. Nature. 2001;413:39–44. doi: 10.1038/35092500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bullock TL, Uter N, Nissan TA, Perona JJ. Amino acid discrimination by a class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase specified by negative determinants. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:395–408. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolfson AD, Uhlenbeck OC. Modulation of tRNAAla identity by inorganic pyrophosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5965–5970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092152799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kinoshita Y, Nishigaki K, Husimi Y. Fluorescence-, isotope- or biotin-labeling of the 5′-end of single-stranded DNA/RNA using T4 RNA ligase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3747–3748. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blanquet S, Mechulam Y, Schmitt E, Vial L. Aminoacyl-transfer RNA maturation. In: Lapointe J, Brakier-Gingras L, editors. Translation Mechanisms. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lyakhov DL, He B, Zhang X, Studier FW, Dunn JJ, McAllister WT. Mutant bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerases with altered termination properties. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:28–40. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Avis JM, Day AG, Garcia GA, Fersht AR. Reaction of modified and unmodified tRNATyr substrates with tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (Bacillus stearothermophilus) Biochemistry. 1993;32:5312–5320. doi: 10.1021/bi00071a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karbstein K, Doudna JA. GTP-dependent formation of a ribonucleoprotein subcomplex required for ribosome biogenesis. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:432–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.