Abstract

We sought to explore whether inherited differences in androgen sensitivity conferred by variation in the length of a CAG repeat in exon 1 of the androgen receptor gene could be correlated with differing manifestations of humoral autoimmunity in men with lupus. In a sample of 15 men with lupus, AR CAG repeat length was linearly correlated with levels of antibodies against extractable nuclear antigens and with the number of diagnostic criteria for lupus. Protein microarrays were used to assess levels of 86 different IgG and IgM autoantibodies in the sera of these patients. IgG autoantibodies were more frequently observed in male lupus patients with longer AR CAG repeat length (>23), while IgM autoantibodies were more prevalent in subjects with shorter CAG repeat length (≤23). These data support a potential role for androgen signaling in the modulation of immunoglobulin class switching processes, with consequent impact on the autoimmune phenotype in men with lupus.

Keywords: Androgens, autoimmunity, genetics, receptors

Introduction

Both animal experimentation and human clinical observation have provided evidence for a protective effect of androgens against the autoimmune processes characteristic of systemic lupus erythematosus. The classic experiments of Talal and colleagues in the NZB/W mouse model of SLE showed that while females of this strain almost uniformly acquired a fatal lupus-like nephritis, treatment with androgens could prevent this disease progression [1–3]. Conversely, intact males were largely unaffected by the disease, but castration resulted in disease progression and mortality [1–3]. Evidence in humans has corroborated this observation. Klinefelter’s syndrome (the most common form of male hypogonadism) has been repeatedly found in association with lupus [4], and in isolated case reports, restoration of normal testosterone levels has been accompanied by remission of features of the autoimmune process [4–8]. Other forms of male hypogonadism, including hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, have also been noted in association with lupus [4, 6], suggesting that androgen deficiency, not the chromosomal abnormalities or pituitary hormone changes present in Klinefelter’s hypogonadism, is the main factor that affects the development of autoimmune phenomena in hypogonadal men.

It is clear, however, that most men with SLE do not have subnormal androgen levels. Studies of male SLE patients have identified evidence of primary hypogonadism (low testosterone accompanied by elevated levels of pituitary LH) in only about 15% of such patients [9–12]. Overt testosterone deficiency may thus have some potential role in disease susceptibility or progression in a subset of male lupus patients, but most male lupus is not accompanied by such hormonal deficiency.

Recent data suggest that inherited differences in androgen transport, signaling, and metabolism play significant roles in the establishment of the normal range of phenotypic virilization of men as well as in the development and manifestations of a number of disease processes [13, 14]. Genetic variation in the androgen receptor (AR) itself has been well documented to affect androgen action. In the extreme example, human syndromes of androgen resistance that comprise a spectrum of phenotypic presentations of failed male development have been shown to result from a variety of mutations in gene encoding the androgen receptor [15, 16]. This receptor protein is a ligand-activated transcription factor with a domain structure that includes a ligand-binding region, a DNA-binding region, and transcriptional activation domains—all of which are required for full activity of the protein.

In addition to its main functional domains, the normal AR gene includes in exon 1 a CAG repeat of variable length (usually between 15 and 30 repeats) that encodes a polyglutamate tract in the N terminal region of the protein beginning at amino acid residue 58 [17]. In 1991, La Spada et al. [18] demonstrated that dramatic expansion of the number of CAG repeats in this region of the gene was the underlying molecular basis of Kennedy’s disease, a form of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy that was sometimes associated with apparent insensitivity to androgen signaling. Subsequent work revealed that even within the normally observed range of variation, the length of this repeat region (and the encoded polyglutamate sequence in the protein) is inversely related to the capacity of the receptor to transactivate a target gene in vitro [19–22]. Although these relative changes in transcriptional regulatory activity in vitro are subtle, they appear to have physiologic relevance. In humans, the variation in androgen sensitivity conferred by different AR CAG repeat lengths has been found to be associated with phenotypic differences in men with Klinefelter’s syndrome [23], with variations in facial and body hair [13], in body composition in older men [24], in HDL levels [25], and in sensitivity to exogenous androgen therapy [26].

We set out to explore whether altered androgen sensitivity might correlate with the development of autoimmune processes. We have genotyped a small cohort of men with lupus erythematosus along with age-matched controls for the exon 1 AR gene CAG repeat length and analyzed the serum of these individuals for autoreactive antibodies using a recently developed autoantigen array methodology. We sought to correlate variations in their serologic expression of autoimmunity with AR CAG length.

Materials and Methods

Samples and Phenotyping

De-identified DNA and serum samples from 15 male subjects with lupus and 12 age-matched control men were obtained from the Dallas Regional Autoimmune Disease Registry (DRADR) biobank. We also attempted to match subjects for ethnicity. The control group included two men of Hispanic ancestry, seven Caucasians, two African-Americans, and one Asian man. The lupus patients included four Hispanics, ten Caucasians, and one man of Asian ancestry. The lupus patients had been diagnosed by their referring rheumatologists on the basis of standardized clinical criteria [27]. Disease features present at the time of each individual’s entry into the DRADR registry were used for our analyses. All human studies were reviewed and approved by the UT Southwestern Institutional Review Board.

AR CAG Repeat Length Determination

Genotyping of the androgen receptor exon 1 (CAG)n repeat length was carried out using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the CAG repeat region and direct sequencing of the amplified product (this X-linked gene is present in single copy in normal XY males). Genomic DNA (100 ng) was used as template for PCR amplification using primers flanking the AR (CAG)n repeat region. Specific primer sequences were: 5′-GCTGTGAAGGTTGCTGTTCCTCAT-3′ and 5′-TCCAGAATCTGTTCCAGAGCGTGC-3′.

PCR amplification products were treated (ExoSap-It; USB, Cleveland, OH) to inactivate primers and dNTPs and were analyzed by DNA sequencing (using each PCR primer) and direct counting of the CAG repeats.

Autoantibodies Directed Against Extractable Nuclear Antigens

A commercially available multiplex immunoassay, the QuantaPlex SLE Profile 8 (Inova Diagnostics, Inc., San Diego, CA), was used to measure autoantibodies against extractable nuclear antigens (ENA). Components in the profile were: Ro(SSA), La(SSB), Sm, RNP, Jo-1, chromatin, Scl-70, and Rib-P. Results were measured on a Luminex 100TM flow cytometer and expressed in Luminex units [28]. Total ENA positivity was calculated for each individual subject as the sum of values for each antigen. We previously validated the use of the Quantaplex assay system against standard clinical measurements of autoantibodies in a test population of lupus patients [28].

Autoantibody Array

Serum samples for all individuals studied were analyzed for IgG and IgM autoantibody expression using an autoantigen array containing 86 autoantigens, as described previously [29, 30]. The arrays were prepared and run in the UT Southwestern Microarray Core Facility. Quantitation of IgG and IgM autoantibodies specific for the array autoantigens was carried out using serum samples (5 μl volumes). Data were normalized for total IgG or IgM levels in each subject. Using the normalized fluorescence intensity data for each specificity, we utilized an arbitrary cutoff for a positive test based on the mean+3 SD of the values observed in the 12 normal control subjects [29]. In the lupus patients, values above this level were scored as positive tests.

Data Analysis

For group data, values are expressed as mean and standard errors of the mean. Significant differences between two groups of continuous variables were determined by t test; dichotomous variables were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. Correlations between continuous variables were analyzed using Pearson’s r. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant. GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for data analysis and graphics.

Results

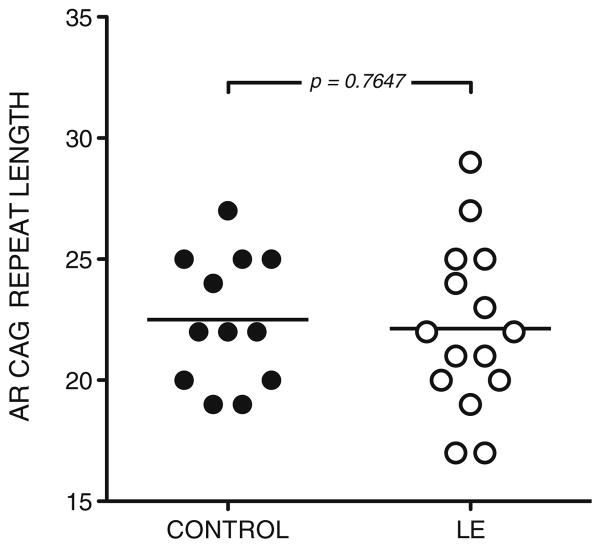

No significant difference in AR CAG repeat length was observed between men with lupus erythematosus and healthy control men (Fig. 1). The group of male lupus subjects had a mean CAG repeat length of 22.13±0.89 compared to 22.50±0.77 for healthy controls. These mean CAG repeat lengths are typical of those reported in the literature for unselected populations [13, 14]. These data suggest that AR CAG repeat length-related alteration in androgen sensitivity is not involved in predisposition to the development of lupus.

Fig. 1.

AR CAG repeat length is similar in healthy control men and in male lupus patients. AR CAG repeat length was determined by PCR amplification and direct sequencing of genomic DNA in 12 controls and 15 lupus patients. Mean AR CAG repeat length was 22.50±0.77 in healthy controls and 22.13±0.89 in lupus patients (p=n.s.)

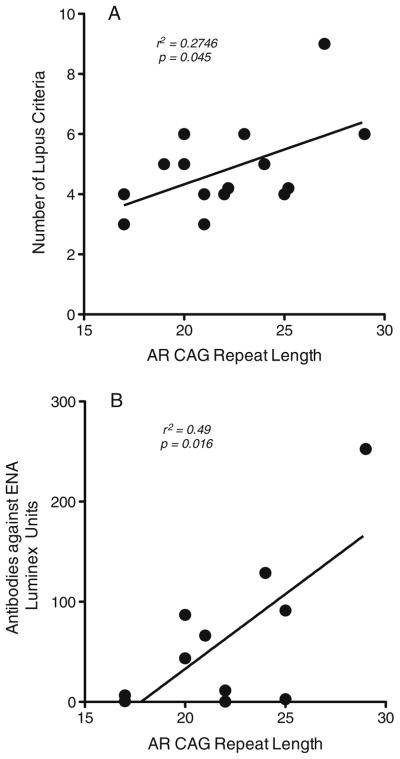

Within the group of men with lupus, however, we found that measures of clinical disease features and of humoral autoimmunity demonstrated an apparent relationship with AR CAG repeat length. The number of American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria [27] identified in each patient at the time of entry into the registry was linearly correlated with AR CAG repeat length (p=0.0450; Fig. 2a). Analysis of patient sera also revealed a significant linear correlation between AR CAG length and the level of autoantibodies directed against ENA (p=0.016; Fig. 2b). These data suggest that male lupus patients with lower intrinsic androgen sensitivity (longer AR exon 1 CAG repeat length) might exhibit more prominent clinical and laboratory manifestations of the autoimmune process.

Fig. 2.

a Number of diagnostic criteria met for the diagnosis of lupus exhibits linear correlation with AR CAG repeat length. Clinical data were obtained for each patient from their earliest clinical evaluation as part of the cohort and are plotted as a function of each individual’s AR CAG repeat length. b Antibodies against extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) in 11 of the male lupus subjects show linear correlation with AR CAG repeat length. ENA was assayed by a commercially available method (Inova), and the level of reactivity is shown as a function of each individual’s CAG repeat length

To pursue the observed correlation of autoantibody expression with AR CAG repeat length, we used autoantigen microarrays to examine a broad range of autoantibody expression (directed against 86 specific autoantigens) in healthy control men and in male lupus patients. Using the normalized fluorescence intensity data for each specificity, we utilized an arbitrary cutoff for a positive test based on the mean+3 SD of the values observed in the 12 normal control subjects [29]. In the lupus patients, values above this level were scored as positive tests. Using this criterion, we found 119 positive tests observed in the 15 lupus patients (Table I). These positive tests were restricted to 37 of the 86 autoantigens on the array. The most frequently observed positives were for autoantibodies directed against chromatin (9 tests), double-stranded RNA (10 tests), double-stranded DNA (13 tests), and single-stranded DNA (12 tests). This autoreactivity against nuclear antigens is characteristic of the disease state.

Table I.

Positive tests for specific autoantibodies in 15 male lupus subjects

| Antigen | IgG

|

IgM

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of positive CAG>23 (n=5) | No. of positive CAG≤23 (n=10) | No. of positive CAG>23 (n=5) | No. of positive CAG≤23 (n=10) | |

| Aggrecan | 1 | |||

| Alpha beta crystallin | 2 | |||

| B2-glycoprotein I | 1 | |||

| C1q | 1 | 2 | ||

| Cardolipin | 1 | 1 | ||

| CENP-A | 1 | 1 | ||

| CENP-B | 1 | |||

| Chondroitin | 2 | |||

| Chromatin | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Collagen IV | 1 | |||

| Cytochrome C | 1 | |||

| dsRNA | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| dsDNA | 3 | 7 | 3 | |

| E. coli lysate | 1 | |||

| H1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| H2A | 1 | 3 | ||

| H2B | 1 | 1 | ||

| H3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| H4 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Histone | 2 | |||

| JO-1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| La/SSB | 1 | |||

| MBP | 1 | |||

| PL-12 | 1 | |||

| PL-7 | 1 | |||

| PM/Scl-100 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rat Glom | 3 | |||

| Ribophosphoprotein P | 1 | |||

| Ro/SSA(60KDa) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ro-52 (SSA) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Scl-70 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| ssDNA | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| U1-snRNP-68 | 2 | |||

| U1-snRNP-A | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| U1-snRNP-BB′ | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| U1-snRNP-C | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| U3-RNP FBL | 1 | |||

| Positive tests | 28 | 30 | 10 | 51 |

| Total tests | 430 | 860 | 430 | 860 |

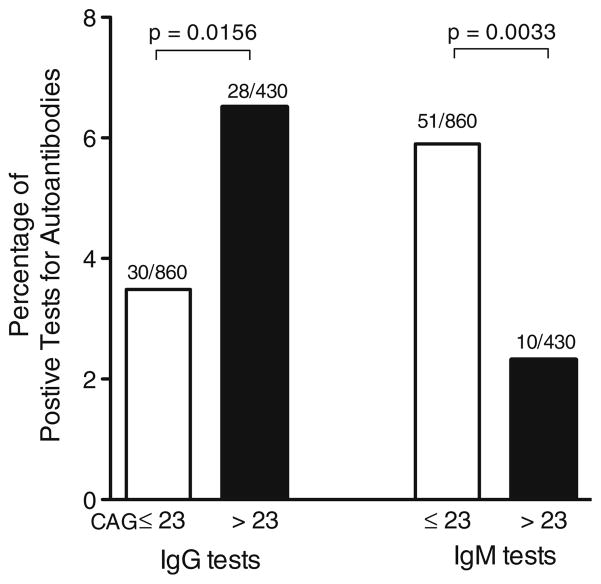

Positive tests for IgG autoantibodies were found to be more frequent in individuals with AR CAG repeat length >23 than in those with lengths ≤23 (p=0.0156 by Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 3, left), while positive IgM autoantibodies were more frequently observed in subjects with AR CAG repeat length of 23 or less (p=0.0033 by Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 3, right). These data suggest that differences in androgen sensitivity conferred by variation in the length of the AR CAG repeat region might influence processes of immunoglobulin class switching in B cells.

Fig. 3.

Positive IgG autoantibody tests occur more frequently in male lupus patients with AR CAG repeat length >23 (top panel, left; p=0.0156), while positive IgM tests are more frequently found in male lupus patients with shorter numbers of repeats (≤23, top panel, right; p=0.0033). Ten lupus patients had CAG repeat lengths ≤23. Five patients had CAG repeat lengths >23. The total number of tests in each group is 86 (the number of autoantigens tested on each array) times the number of subjects in the group

Discussion

These data are the first to suggest a relationship between genetic variation in the androgen receptor gene and an alteration of the autoimmune response. Specifically, we observed in men with lupus an apparent linear correlation between AR CAG repeat length and levels of antibodies against extractable nuclear antigens. We also found significant correlation between the number of standard clinical diagnostic criteria for lupus observed in individual subjects and the length of their respective AR CAG repeat region. Previous observations in humans have suggested that AR CAG repeat length over 25 is associated with phenotypic evidence of attenuated androgen action [13, 14]. We found that longer AR CAG repeat length (and consequent diminution in the sensitivity of the androgen receptor) is associated with a shift to IgG predominant humoral autoimmunity compared to autoantibody expression in male lupus patients with shorter AR CAG repeat length. Intrinsic strain-specific androgen sensitivity was first postulated as an important factor in murine humoral immune responsiveness over 30 years ago [31]; the molecular genetic basis for this inherited variation in hormone action in mice remains unknown. Our findings in human subjects support the notion that genetically determined variation in intrinsic androgenic hormone responsiveness might impact humoral autoimmunity.

We recognize a number of limitations of our study. First, our sample size is small. Only a minority of patients with lupus is male, and even with the resources of a registry, we had the opportunity to assess only 15 subjects. Nevertheless, the rather striking findings of autoantibody responses in these men reach statistical significance for several corroborative parameters. The study is also limited by its retrospective design. The available clinical data included only the diagnostic criteria recognized at the time of entry into the registry. Future prospective studies with ongoing assessments of more robust indices of clinical disease activity and progression (e.g., SLEDAI [32, 33] and SLICC [34] scores) will be of considerable interest to define whether the observed alterations in humoral autoimmunity are of clinical significance. Finally, these observations do not establish whether gradations in immune function or in expression of autoimmune responses might be observed over the full range of AR CAG repeat variability or whether some “threshold” of AR CAG repeat length might define a level of androgen sensitivity at which altered immune responses are demonstrable. In vitro, the transactivation capacity of the androgen receptor has been demonstrated to diminish monotonically by an average of 1.7% for each addition CAG repeat within the range of 16–35 repeats [35]. Our subjects with lupus had AR CAG lengths that spanned the range from 17 to 29, and while our analysis as a dichotomous variable (long vs. short repeats) revealed evidence of an influence on autoantibody class switching, our subject numbers do not suffice to define a linear relationship between IgG or IgM autoantibody expression over the entire range of AR CAG repeat length. Further studies will be needed to address this point. We believe that either continuous variability or a “threshold” model for the effect would be consistent with known molecular mechanisms of androgen action.

Over 30 years ago, Talal and colleagues, studying the NZB/W F1 mouse model of lupus, reported that the development of immune complex glomerulonephritis in these animals was accompanied by a change in the class of the predominant circulating anti-DNA immunoglobulin type from IgM to IgG [1–3]. They also noted that the switch to IgG class autoantibodies was accelerated in females compared to males and that this early production of IgG autoreactivity was recapitulated in males who had been castrated neonatally. Furthermore, androgen administration to females, or normalization of androgen levels in castrate males, maintained the IgM autoantibody levels and prevented the rise in IgG. Recent studies in mouse models of androgen insensitivity (including B cell-specific AR knockouts) have also shown that defects in androgen action are associated with increases in serum IgG autoantibodies directed against dsDNA, while levels of IgM autoantibodies of the same specificity were unaltered [36]. Our observations are the first data in humans that suggest a potential role for inherited androgen sensitivity in modulating the IgM to IgG class switch in the setting of autoimmunity. Whether these are direct effects or indirect results of androgen action on other components of the immune system remains a matter of speculation at the present.

Explorations into the mechanisms by which gonadal steroid hormones might influence immunoglobulin class switching have only recently begun. Activation-induced cytosine deaminase is a critical enzyme that is required for somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination processes that underlie the maturation of the humoral immune response [37]. Recent work has identified estrogenic hormones as potent upregulators of expression of aicda, the murine gene encoding this deaminase [38]; progestins have been found to function as transcriptional inhibitors of this gene [38, 39]. Available data on the estrogen response have supported both direct transcriptional regulation through estrogen response elements in the aicda promoter[38] as well as indirect regulation via effects on the promoter of the HoxC4 gene, an important regulator of aicda gene expression [40, 41]. Whether androgens exert such effects on the regulation of processes essential for immunoglobulin class switching is unexplored, but the data presented here suggest that similar mechanisms might be operative for this class of steroid hormones. Our previous observations on the effects of androgens on B cell development demonstrated effects of these hormones acting through bone marrow stromal elements to alter early stages of B cell maturation [42]. Since somatic hypermutation and IgM to IgG class switching occur in more mature cells in the periphery, it seems likely that these peripheral lymphoid cells themselves would be the targets of such androgen actions. Further studies of these cellular and molecular mechanisms of androgen action on immune system components will be of considerable interest for the elucidation of the apparent protective effects of androgens in the setting of autoimmunity.

Acknowledgments

Pilot funding for this project was awarded to AHT with WJK as mentor from NIH grant RR024982 (North Central Texas Clinical and Translational Science Initiative, Milton Packer, M. D., Principal Investigator). Fellowship support for AHT was provided by NIH training grant T32 DK007307 (WJK, Principal Investigator). The Dallas Regional Autoimmune Disease Registry is directed by David Karp, M.D., Ph.D. and supported by NIH grant P50 AR055503 (C Mohan, P.I.). We appreciate the advice and guidance of Quan Li, Ph.D., Director of the UT Southwestern Microarray Core Facility. Expert technical assistance was provided by Michelle Christadoss.

Contributor Information

Alex H. Tessnow, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

Nancy J. Olsen, Division of Rheumatology, The Pennsylvania State University—College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

William J. Kovacs, Email: wkovacs@hmc.psu.edu, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, The Pennsylvania State University—College of Medicine, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

References

- 1.Roubinian J, Talal N, Siiteri PK, Sadakian JA. Sex hormone modulation of autoimmunity in NZB/NZW mice. Arthritis Rheum. 1979;22:1162–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780221102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roubinian JR, Papoian R, Talal N. Androgenic hormones modulate autoantibody responses and improve survival in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. 1977;59:1066–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI108729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roubinian JR, Talal N, Greenspan JS, Goodman JR, Siiteri PK. Effect of castration and sex hormone treatment on survival, anti-nucleic acid antibodies, and glomerulonephritis in NZB/NZW F1 mice. J Exp Med. 1978;147:1568–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.6.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oktenli C, Yesilova Z, Kocar IH, Musabak U, Ozata M, Inal A, et al. Study of autoimmunity in Klinefelter’s syndrome and idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Immunol. 2002;22:137–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1015467912592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bizzarro A, Valentini G, Di Martino G, DaPonte A, De Bellis A, Iacono G. Influence of testosterone therapy on clinical and immunological features of autoimmune diseases associated with Klinefelter’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:32–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-1-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jimenez-Balderas FJ, Tapia-Serrano R, Fonseca ME, Arellano J, Beltran A, Yanez P, et al. High frequency of association of rheumatic/autoimmune diseases and untreated male hypogonadism with severe testicular dysfunction. Arthritis Res. 2001;3:362–7. doi: 10.1186/ar328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kocar IH, Yesilova Z, Ozata M, Turan M, Sengul A, Ozdemir I. The effect of testosterone replacement treatment on immunological features of patients with Klinefelter’s syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:448–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen NJ, Kovacs WJ. Case report: testosterone treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus in a patient with Klinefelter’s syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 1995;310:158–60. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inman RD, Jovanovic L, Markenson JA, Longcope C, Dawood MY, Lockshin MD. Systemic lupus erythematosus in men. Genetic and endocrine features. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:1813–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller MH, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Killinger DW. Systemic lupus erythematosus in males. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983;62:327–34. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mok CC, Lau CS. Profile of sex hormones in male patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2000;9:252–7. doi: 10.1191/096120300680198926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sequeira JF, Keser G, Greenstein B, Wheeler MJ, Duarte PC, Khamashta MA, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: sex hormones in male patients. Lupus. 1993;2:315–7. doi: 10.1177/096120339300200507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canale D, Caglieresi C, Moschini C, Liberati CD, Macchia E, Pinchera A, et al. Androgen receptor polymorphism (CAG repeats) and androgenicity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;63:356–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zitzmann M. Mechanisms of disease: pharmacogenetics of testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007;4:161–6. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McPhaul MJ. Androgen receptor mutations and androgen insensitivity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;198:61–7. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPhaul MJ. Molecular defects of the androgen receptor. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:181–94. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tilley WD, Marcelli M, Wilson JD, McPhaul MJ. Characterization and expression of a cDNA encoding the human androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:327–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.La Spada AR, Wilson EM, Lubahn DB, Harding AE, Fischbeck KH. Androgen receptor gene mutations in X-linked spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Nature. 1991;352:77–9. doi: 10.1038/352077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beilin J, Ball EM, Favaloro JM, Zajac JD. Effect of the androgen receptor CAG repeat polymorphism on transcriptional activity: specificity in prostate and non-prostate cell lines. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;25:85–96. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irvine RA, Ma H, Yu MC, Ross RK, Stallcup MR, Coetzee GA. Inhibition of p160-mediated coactivation with increasing androgen receptor polyglutamine length. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:267–74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tut TG, Ghadessy FJ, Trifiro MA, Pinsky L, Yong EL. Long polyglutamine tracts in the androgen receptor are associated with reduced trans-activation, impaired sperm production, and male infertility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;82:3777–82. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chamberlain NL, Driver ED, Miesfeld RL. The length and location of CAG trinucleotide repeats in the androgen receptor N-terminal domain affect transactivation function. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3181–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinn AR, Ramos P, Elder FF, Kowal K, Samango-Sprouse C, Ross JL. Androgen receptor CAGn repeat length influences phenotype of 47, XXY (Klinefelter) syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5041–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapauw B, Goemaere S, Crabbe P, Kaufman JM, Ruige JB. Is the effect of testosterone on body composition modulated by the androgen receptor gene CAG repeat polymorphism in elderly men? Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:395–401. doi: 10.1530/EJE-06-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zitzmann M, Brune M, Kornmann B, Gromoll J, von Eckardstein S, von Eckardstein A, et al. The CAG repeat polymorphism in the AR gene affects high density lipoprotein cholesterol and arterial vasoreactivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4867–73. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zitzmann M, Nieschlag E. Androgen receptor gene CAG repeat length and body mass index modulate the safety of long-term intramuscular testosterone undecanoate therapy in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3844–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wandstrat AE, Carr-Johnson F, Branch V, Gray H, Fairhurst AM, Reimold A, et al. Autoantibody profiling to identify individuals at risk for systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2006;27:153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li QZ, Zhou J, Wandstrat AE, Carr-Johnson F, Branch V, Karp DR, et al. Protein array autoantibody profiles for insights into systemic lupus erythematosus and incomplete lupus syndromes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:60–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li QZ, Xie C, Wu T, Mackay M, Aranow C, Putterman C, et al. Identification of autoantibody clusters that best predict lupus disease activity using glomerular proteome arrays. J Clin Invest. 2006;115:3428–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI23587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohn DA. Sensitivity to androgen. A possible factor in sex differences in the immune response. Clin Exp Immunol. 1979;38:218–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:288–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Goldsmith CH, Fortin P, Ginzler E, Gordon C, et al. The reliability of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:809–13. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchanan G, Yang M, Cheong A, Harris JM, Irvine RA, Lambert PF, et al. Structural and functional consequences of glutamine tract variation in the androgen receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1677–92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altuwaijri S, Chuang KH, Lai KP, Lai JJ, Lin HY, Young FM, et al. Susceptibility to autoimmunity and B cell resistance to apoptosis in mice lacking androgen receptor in B cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:444–53. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honjo T, Kinoshita K, Muramatsu M. Molecular mechanism of class switch recombination: linkage with somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:165–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.090501.112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pauklin S, Sernandez IV, Bachmann G, Ramiro AR, Petersen-Mahrt SK. Estrogen directly activates AID transcription and function. J Exp Med. 2009;206:99–111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pauklin S, Petersen-Mahrt SK. Progesterone inhibits activation-induced deaminase by binding to the promoter. J Immunol. 2009;183:1238–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mai T, Zan H, Zhang J, Hawkins JS, Xu Z, Casali P. Estrogen receptors bind to and activate the HOXC4/HoxC4 promoter to potentiate HoxC4-mediated activation-induced cytosine deaminase induction, immunoglobulin class switch DNA recombination, and somatic hypermutation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37797–810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park SR, Zan H, Pal Z, Zhang J, Al-Qahtani A, Pone EJ, et al. HoxC4 binds to the promoter of the cytidine deaminase AID gene to induce AID expression, class-switch DNA recombination and somatic hypermutation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:540–50. doi: 10.1038/ni.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsen NJ, Gu X, Kovacs WJ. Bone marrow stromal cells mediate androgenic suppression of B lymphocyte development. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1697–704. doi: 10.1172/JCI13183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]