Abstract

Rhodospirillum rubrum (Esmarch 1887) Molisch 1907 is the type species of the genus Rhodospirillum, which is the type genus of the family Rhodospirillaceae in the class Alphaproteobacteria. The species is of special interest because it is an anoxygenic phototroph that produces extracellular elemental sulfur (instead of oxygen) while harvesting light. It contains one of the most simple photosynthetic systems currently known, lacking light harvesting complex 2. Strain S1T can grow on carbon monoxide as sole energy source. With currently over 1,750 PubMed entries, R. rubrum is one of the most intensively studied microbial species, in particular for physiological and genetic studies. Next to R. centenum strain SW, the genome sequence of strain S1T is only the second genome of a member of the genus Rhodospirillum to be published, but the first type strain genome from the genus. The 4,352,825 bp long chromosome and 53,732 bp plasmid with a total of 3,850 protein-coding and 83 RNA genes were sequenced as part of the DOE Joint Genome Institute Program DOEM 2002.

Keywords: facultatively anaerobic, photolithotrophic, mesophile, Gram-negative, motile, Rhodospirillaceae, Alphaproteobacteria, DOEM 2002

Introduction

Strain S1T (= ATCC 11170 = DSM 467) is the neotype strain of the species Rhodospirillum rubrum, which is the type species of the genus Rhodospirillum. The genus name is derived from the ancient Greek term rhodon, meaning rose, and the Latin spira, meaning coil. Rubrum is Latin for red. Currently R. rubrum is one out of only four species with a validly described name in this genus. Strain S1T (van Niel) was designated as the neotype strain for R. rubrum by Pfennig and Trüper in 1971 [1], with the description of the strain in complete agreement with the species description given by van Niel in 1944 [2] for the initial deposition at the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). A comparative genomic analysis with the only other publicly available rhodospirillal genome was recently published by Lu et al. [3]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for R. rubrum S1T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

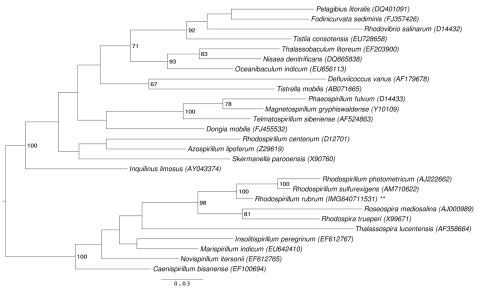

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of R. rubrum S1T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the four 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome do not differ from each other, and do not differ from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence (X87278), which contains two ambiguous base calls.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of R. rubrum S1T relative to the other type strains within the family Rhodospirillaceae. The 16S rRNA accessions were selected from the most recent release of the All-Species-Living-Tree-Project [4] as far as possible. The tree was inferred from 1,361 aligned characters [5,6] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [7]. Rooting was done initially using the midpoint method [8] and then checked for its agreement with the current classification (Table 1). The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers to the right of bifurcations are support values from 550 bootstrap replicates [9] if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [10] are labeled with one asterisk, those also listed as 'Complete and Published' with two asterisks.

Table 1. Classification and general features of R. rubrum according to the MIGS recommendations [11].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [12] | |

| Phylum ‘Proteobacteria’ | TAS [13] | ||

| Class Alphaproteobacteria | TAS [14,15] | ||

| Order Rhodospirillales | TAS [16,17] | ||

| Family Rhodospirillaceae | TAS [16,17] | ||

| Genus Rhodospirillum | TAS [17-21] | ||

| Species Rhodospirillum rubrum | TAS [17,18,22] | ||

| Type strain S1 | TAS [1,2] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | NAS | |

| Cell shape | spiral-shaped | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | not reported | ||

| Temperature range | mesophile | NAS | |

| Optimum temperature | 25-30°C | NAS | |

| Salinity | not reported | ||

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | facultative anaerobe | TAS [2] |

| Carbon source | numerous 1- and multi-C compounds | TAS [2] | |

| Energy metabolism | photolithotroph, photoautotroph, aerobic heterotroph, fermentation carbon monoxide |

TAS [2,23] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | fresh water | NAS |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [24] | |

| Isolation | not reported | ||

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | not reported | |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1941 | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [25]. If the evidence code is IDA, the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

A representative genomic 16S rRNA sequence of strain S1T was compared using NCBI BLAST under default settings (e.g., considering only the high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) from the best 250 hits) with the most recent release of the Greengenes database [26] and the relative frequencies, weighted by BLAST scores, of taxa and keywords (reduced to their stem [27]) were determined. The five most frequent genera were Rhizobium (41.6%), Rhodospirillum (30.8%), Aquaspirillum (6.2%), Rhodocista (4.2%) and Novosphingobium (3.5%) (130 hits in total). Regarding the 16 hits to sequences from members of the species, the average identity within HSPs was 98.5%, whereas the average coverage by HSPs was 97.8%. Regarding the five hits to sequences from other members of the genus, the average identity within HSPs was 95.3%, whereas the average coverage by HSPs was 95.0%. Among all other species, the one yielding the highest score was Rhodospirillum photometricum, which corresponded to an identity of 96.0% and an HSP coverage of 96.9%. (Note that the Greengenes database uses the INSDC (= EMBL/NCBI/DDBJ) annotation, which is not an authoritative source for nomenclature or classification.) The highest-scoring environmental sequence was AM691104 ('Rhodobacteraceae clone EG16'), which showed an identity of 91.7% and an HSP coverage of 97.2%. The five most frequent keywords within the labels of environmental samples which yielded hits were 'ocean' (2.5%), 'microbi' (2.4%), 'soil' (2.1%), 'skin' (1.8%) and 'aquat/rank' (1.8%) (120 hits in total). Environmental samples which yielded hits of a higher score than the highest scoring species were not found.

Cells of R. rubrum stain Gram-negative, are motile, vibrioid to short spiral-shaped with a size of 0.8-1 µm (Figure 2). Colonies are purple-colored because the cells contain a carotenoid pigment required to gather light energy for photosynthesis. R. rubrum does not produce oxygen, but elemental sulfur as a by-product of photosynthesis, using bacteriochlorophyll, which enables the absorbtion of light at wavelengths longer than those absorbed by plants. Strain S1T is a facultative anaerobe that uses alcoholic fermentation under low oxygen conditions, but respiration under aerobic conditions. Photosynthesis is genetically suppressed under aerobic conditions; R. rubrum is colorless under these conditions. The regulation of the photosynthetic machinery is still poorly understood, though the organism is phototactic [28]. The RuBisCO (Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase) of R. rubrum is highly unusual in its simplicity as a homodimer [29].

Figure 2.

Scanning Electron micrograph of R. rubrum S1T generated from a culture of DSM 467

R. rubrum is a well-established model organism for studies on nitrogen fixation and the organism possesses two related but distinct nitrogenase systems that utilize distinct metals at the active site [30]. The post-translational regulation of nitrogenase in R. rubrum is relatively unusual in that it utilizes a reversible ADP-ribosylation process [31-35]. The organism has also been used to study bacterial growth on carbon monoxide as an energy source [23], and its carbon monoxide sensor, termed CooA, has been the paradigm for such sensors [36]. R. rubrum provides several potential biotechnological applications, e.g. the accumulation of PHB precursors for plastic production in the cell, as well as the production of hydrogen fuel.

Chemotaxonomy

The composition of the R. rubrum cell wall has previously been reported in various publications. The main fatty acids of strain S1T are unbranched, with unsaturated acids C16:1 w7c (34.1%), C18:1 w7c/12t/9t (32.8%) and C18:1 2OH (6.9%) dominating over a minority of saturated acids: C16:0 (11.6%) and C14:0 (4.0%) [analyzed with a culture of CCUG 17859, www.ccug.se].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of the DOE Joint Genome Institute Program DOEM 2002. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes On Line Database [10] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two genomic Sanger libraries: 3 kb pUC18c library, fosmid (40 kb) library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 11.0 × Sanger |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Critica complemented with the output of Glimmer |

| INSDC ID | CP000230 (chromosome) CP000231 (plasmid) |

|

| GenBank Date of Release | December 13, 2005 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc00396 | |

| NCBI project ID | 58 | |

| Database: IMG | 637000241 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | ATCC 11170 |

| Project relevance | Bioenergy |

Strain history

The history of strain S1T starts with C. B. van Niel (strain ATH 1.1.1, probably 1941) → S.R. Elsden strain S1 → NCI(M)B 8255 → ATCC 11170, from which later on DSM 467, LMG 4362 and CCRC 16403 were derived.

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

The culture of strain S1T, ATCC 11170, used to prepare genomic DNA (gDNA) for sequencing was only 3 transfers away from the original deposit. The culture used to prepare genomic DNA (gDNA) for sequencing, was purified from the original deposit on rich SMN [37] plates, and then grown in SMN liquid medium aerobically. MasterPure Genomic DNA Purification Kit from Epicentre (Madison, WI) was used for total DNA isolation from R. rubrum, with a few minor modifications as described previously [38]. One-half to 1 ml of cells was used for DNA isolation. After isopropanol precipitation, DNA was resuspended in 500 µl of 0.1 M sodium acetate and 0.05 M MOPS (pH 8.0), then reprecipitated with 2 volume of ethanol. This step was repeated twice and significantly improved the quality of DNA. The purity, quality and size of the bulk gDNA preparation were assessed by JGI according to DOE-JGI guidelines.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using the Sanger sequencing platform (3 kb and 40 kb DNA libraries). All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at [39]. The Phred/Phrap/Consed [40] software package was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment. After the shotgun stage, reads were assembled with parallel phrap (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) [41]. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification. A total of 847 additional custom primer reactions were necessary to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The completed genome sequence contains 62,976 reads, achieving an average of 11-fold sequence coverage with an error rate of less than 1 in 50,000.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using two gene modeling programs, Glimmer [42] and Critica [43] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline. The two sets of gene calls were combined using Critica as the preferred start call for genes with the same stop codon. Genes with less than 80 amino acids which were predicted by only one of the gene callers and had no Blast hit in the KEGG database at 1e-05, were deleted. This was followed by a round of manual curation to eliminate obvious overlaps. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. These data sources were combined to assert a product description for each predicted protein. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [44], TMHMM [45], and signalP [46]. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) platform developed by the Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, CA, USA [47].

Genome properties

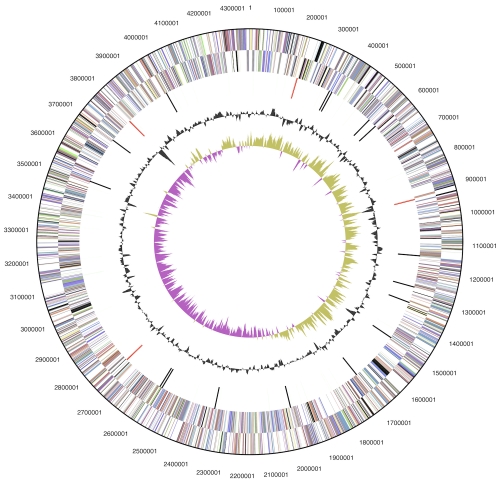

The genome consists of a 4,352,825 bp long chromosome with a 65% G+C content and a 53,732 bp plasmid with 60% G+C content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 3,933 genes predicted, 3,850 were protein-coding genes, and 83 RNAs; nine pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (72.7%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,406,557 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 3,911,312 | 88.76% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,880,951 | 65.38% |

| Number of replicons | 2 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 1 | |

| Total genes | 3,933 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 83 | 2.11% |

| rRNA operons | 4 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 3,850 | 97.89% |

| Pseudo genes | 9 | 0.23% |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,861 | 72.74% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 518 | 13.17% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,048 | 77.50% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 3,235 | 82.25% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 776 | 19.73% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 734 | 18.66% |

| CRISPR repeats | 13 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome (plasmid map not shown). From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 159 | 4.6 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 236 | 6.9 | Transcription |

| L | 136 | 4.0 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 2 | 0.1 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 36 | 0.9 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 56 | 1.6 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 271 | 7.9 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 204 | 5.9 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 121 | 3.5 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 69 | 2.1 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 127 | 3.7 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 228 | 6.6 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 173 | 5.0 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 341 | 9.9 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 69 | 2.0 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 160 | 4.7 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 126 | 3.7 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 222 | 6.5 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 67 | 2.0 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 367 | 10.7 | General function prediction only |

| S | 261 | 7.6 | Function unknown |

| - | 885 | 22.5 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Brian J. Tindall and his team (DSMZ) for growing a R. rubrum culture for the EM image. The work conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute was supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, and was also supported by NIGMS grant GM65891 to G. P. R.

References

- 1.Pfennig N, Trüper HG. Type and neotype strains of the species of phototrophic bacteria maintained in pure culture. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1971; 21:19-24 10.1099/00207713-21-1-19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Niel CB. The culture, general physiology, morphology, and classification of the non-sulfur purple and brown bacteria. Bacteriol Rev 1944; 8:1-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu YK, Marden J, Han M, Swingley WD, Mastrian SD, Chowdhury SR, Hao J, Helmy T, Kim S, Kurdoglu AA, et al. Metabolic flexibility revealed in the genome of the cyst-forming α-1 proteobacterium Rhodospirillum centenum. BMC Genomics 2010; 11:325 10.1186/1471-2164-11-325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarza P, Ludwig W, Euzéby J, Amann R, Schleifer KH, Glöckner FO, Rosselló-Móra R. Update of the all-species living tree project based on 16S and 23S rRNA sequence analyses. Syst Appl Microbiol 2010; 33:291-299 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess PN, De Moraes Russo CA. An empirical test of the midpoint rooting method. Biol J Linn Soc Lond 2007; 92:669-674 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00864.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The genomes on line database (GOLD) in 2009: Status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms. Proposal for the domains Archaea and Bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: DJ Brenner, NR Krieg, JT Staley, G M Garrity (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition, vol. 2 (The Proteobacteria), part B (The Gammaproteobacteria), Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Validation List No. 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class I. Alphaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfennig N, Trüper HG. Higher taxa of the phototrophic bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1971; 21:17-18 10.1099/00207713-21-1-17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molisch. Die Purpurbakterien nach neuen Untersuchungen. G. Fischer, Jena I-VII, 1907, pp. 1-95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfennig N, Trüper HG. Genus I. Rhodospirillum Molisch 1907, 24. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, Eighth Edition, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1974, p. 26-29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imhoff JF, Trüper HG, Pfennig N. Rearrangements of the species and genera of the phototrophic "purple nonsulfur bacteria.". Int J Syst Bacteriol 1984; 34:340-343 10.1099/00207713-34-3-340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imhoff JF, Petri R, Süling J. Reclassification of species of the spiral-shaped phototrophic purple non-sulfur bacteria of the alpha-Proteobacteria: description of the new genera Phaeospirillum gen. nov., Rhodovibrio gen. nov., Rhodothalassium gen. nov. and Roseospira gen. nov. as well as transfer of Rhodospirillum fulvum to Phaeospirillum fulvum comb. nov., of Rhodospirillum molischianum to Phaeospirillum molischianum comb. nov., of Rhodospirillum salinarum to Rhodovibrio salexigens. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1998; 48:793-798 10.1099/00207713-48-3-793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esmarch E. Über die Reinkultur eines Spirillum. Zentralblatt fur Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde, Infektionskrankheiten und Hygiene. Abteilung I 1887; 1:225-230 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerby RL, Ludden PW, Roberts GP. CO-dependent growth of Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol 1995; 177:2241-2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.BAuA Classification of bacteria and archaea in risk groups. TRBA 2005; 466:292 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:5069-5072 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter MF. An algorithm for suffix stripping. Program: electronic library and information systems 1980; 14:130-137.

- 28.Harayama S, Iino T. Phototaxis and membrane potential in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol 1977; 131:34-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Branden CI, Schneider G, Lindqvist Y, Andersson I, Knight S, Lorimer GH. X-ray structural studies of Rubisco from Rhodospirillum rubrum and spinach. Phil Trans Royal Soc London, Ser B. Biol Sci 1986; 313:359-365 10.1098/rstb.1986.0043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehman LJ, Roberts GP. Identification of an alternate nitrogenase in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol 1991; 173:5705-5711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teixeira PF, Jonsson A, Frank M, Wang H, Nordlund S. Interaction of the signal transduction protein GlnJ with the cellular targets AmtB1, GlnE and GlnD in Rhodospirillum rubrum: dependence on manganese, 2-oxoglutarate and the ADP/ATP ratio. Microbiology 2008; 154:2336-2347 10.1099/mic.0.2008/017533-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selao TT, Nordlund S, Norén A. Comparative proteomic studies in Rhodospirillum rubrum grown under different nitrogen conditions. J Proteome Res 2008; 7:3267-3275 10.1021/pr700771u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfe DM, Zhang Y, Roberts GP. Specificity and regulation of interaction between the PII and AmtB1 proteins in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol 2007; 189:6861-6869 10.1128/JB.00759-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonsson A, Teixeira PF, Nordlund S. The activity of adenylyltransferase in Rhodospirillum rubrum is only affected by alpha-ketoglutarate and unmodified PII proteins, but not by glutamine, in vitro. FEBS J 2007; 274:2449-2460 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pope MR, Murrell SA, Ludden PW. Covalent modification of the iron protein of nitrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum by adenosine diphosphoribosylation of a specific arginine residue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1985; 82:3173-3177 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts GP, Youn H, Kerby RL, Conrad M. CooA, a paradigm for gas sensing regulatory proteins. J Inorg Biochem 2005; 99:280-292 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzmaurice WP, Saari LL, Lowery RG, Ludden PW, Roberts GP. Genes coding for the reversible ADP-ribosylation system of dinitrogenase reductase of Rhodospirillum rubrum. Mol Gen Genet 1989; 218:340-347 10.1007/BF00331287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Pohlmann EL, Ludden PW, Roberts GP. Mutagenesis and functional characterization of glnB, glnA and nifA genes from Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol 2000; 182:983-992 10.1128/JB.182.4.983-992.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The DOE Joint Genome Institute. http://www.jgi.doe.gov

- 40.Phrap and Phred for Windows, MacOS, Linux, and Unix. www.phrap.com

- 41.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter JC, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delcher AL, Bratke K, Powers E, Salzberg S. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007; 23:673-679 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Badger JH, Olsen GJ. CRITICA: Coding region identification tool invoking comparative analysis. Mol Biol Evol 1999; 16:512-524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 10.1093/nar/25.5.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dyrløv Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol 2004; 340:783-795 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Markowitz VM, Szeto E, Palaniappan K, Grechkin Y, Chu K, Chen IMA, Dubchak I, Anderson I, Lykidis A, Mavromatis K, et al. The Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) system in 2007: data content and analysis tool extensions. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D528-D533 10.1093/nar/gkm846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]