Abstract

In the past few years, the field of metagenomics has been growing at an accelerated pace, particularly in response to advancements in new sequencing technologies. The large volume of sequence data from novel organisms generated by metagenomic projects has triggered the development of specialized databases and tools focused on particular groups of organisms or data types. Here we describe a pipeline for the functional annotation of viral metagenomic sequence data. The Viral MetaGenome Annotation Pipeline (VMGAP) pipeline takes advantage of a number of specialized databases, such as collections of mobile genetic elements and environmental metagenomes to improve the classification and functional prediction of viral gene products. The pipeline assigns a functional term to each predicted protein sequence following a suite of comprehensive analyses whose results are ranked according to a priority rules hierarchy. Additional annotation is provided in the form of enzyme commission (EC) numbers, GO/MeGO terms and Hidden Markov Models together with supporting evidence.

Keywords: J. Craig Venter Institute, metagenomic annotation, viral annotation

Introduction

Viruses are the most abundant biological agents and comprise the majority of the biodiversity on Earth [1-3]. However, understanding the population biology and dynamics of viral communities in the environment is difficult because their hosts (predominantly microbes) are unknown and cannot be grown in culture. Furthermore, the study of viral diversity is hampered by the lack of a universally conserved gene across all viral species, analogous to rDNA genes in cellular organisms. Metagenomic shotgun sequence analysis of viral communities helps to alleviate these constraints and is currently the most widely used approach to study the biodiversity of viral populations isolated directly from the environment.

The recent development of faster and cheaper next generation sequencing technologies has contributed to an exponential growth of metagenomic sequencing data, transforming our view of the microbial world. Despite the advancements in sequencing technology, functional annotation of metagenomic sequences is still very challenging. Metagenomic data originate from heterogeneous microbial communities, are usually noisy and partial, and reads frequently contain truncated open reading frames (ORFs). Complicating this landscape, the vast majority of viruses isolated from environmental samples are novel and consequently most of their genes do not have homologous sequences in the public databases, making functional annotation even more difficult.

Currently, there are a number of publicly available bioinformatics tools for the taxonomic (Ribosomal Database Project(RDP) [4],Greengenes [5],MEGAN [6], pplacer [7]) and functional (IMG/M [8], CAMERA [9], MG-RAST [10]) analysis of metagenomes. While IMG/M facilitates the functional analysis of pre-selected metagenomic data, it does not support the input and analysis of external user data. CAMERA allows for the construction of customized workflows for the analysis of external metagenomic data including functional annotation using RAMMCAP based on PFAM, TIGRFAM and COGs. MG-RAST is an alternative web-resource that performs metabolic reconstructions using SEED subsystems [11] and builds automated phylogenetic profiles of metagenomic data provided by the scientific community. While MG-RAST has been used for the functional annotation of multiple viral metagenomes [12], it is not ideal for the characterization of viral metagenomic data since functional classification is solely dependent on similarity to FIGfams [13], protein families developed from manually curated bacterial and archaeal proteins. Another limitation of this tool is that it does not search for conserved protein domains or motifs that could provide additional clues about the functional roles of genes present in metagenomic samples.

Here we describe a viral metagenomic annotation pipeline (VMGAP) that is currently utilized at the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) for the functional annotation of viral metagenomic datasets. This pipeline incorporates a number of HMM and PSSM searches and makes use of a suite of specialized databases to improve the functional identification of viral genes. Results can be imported into JCVI Metagenomic Reports (METAREP) [14], an open source tool for high performance comparative metagenomics that allows users to view, query, browse and compare extremely large annotated metagenomic data sets.

Requirements

The VMGAP requires a protein multi fasta file as input and the local installation of several open source programs, packages and public databases. The required software and packages are HMMER [15], NCBI-toolkit (blast searches [16]), SignalP (signal peptide prediction [17]) [18]and TMHMM [19,20] and PRIAM (Ecnumber prediction [21]) [22]. Among the public databases searched by the pipeline are GenBank NRDB, GenBank environmental databases ENV_NT and ENV_NR, UniProtDB [23], OMNIOMEDB [24], PFAM [25] and TIGRFAM [26] HMMDBs, ACLAME protein and HMMDBs [27],GenBank CDDDB [28] and pfam2gomappingsDB [11].

Procedure

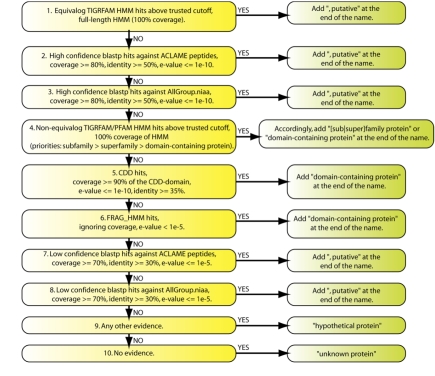

The JCVI VMGAP consists of two consecutive steps: (1) database searches and (2) functional assignments. The pipeline uses as input a multifasta file containing the translations of all open reading frames (ORFs) predicted in a metagenomic sample. Protein coding genes are predicted using the structural annotation pipeline [29], that is based on a combination of naïve 6-frame translations and MetaGeneAnnotator [30,31], an ab initio gene finder program that uses empirical data including sequence-based composition, distance and orientation of genes of completely sequenced genomes to identify protein coding genes. Once uploaded, protein sequences are used to query several databases to identify protein features and similarities as schematically represented in Figure 1. During step 1, the VMGAP performs the following sequence similarity searches:

Figure 1.

Naming rules used for functional annotation of the VMGAP.

1) Blastp searches against a non-redundant protein database

The non-redundant protein database encompasses several public protein databases (GenBank NR, UniProt, PIR and OMNIOME) where each set of redundant peptides are condensed into a single database entry without losing useful information recorded in the fasta headers, such as EC numbers, product names, and taxon identification number. The VMGAP reports the top 50 hits with e-values ≤1x10-5.

2) Blastp searches against the ACLAME database

ACLAME is a public protein database of mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including bacteriophages, transposons and plasmids [27]. Proteins are organized into families based on their function and sequence similarity, and families of 4 or more members are manually annotated with functional assignments using GO and MeGO terms (an ontology dedicated to MGEs developed by ACLAME). All blastp hits with e-values ≤1x10-5 are reported.

3) Blastp and tblastn searches against environmental protein databases

The VMGAP queries three different environmental composite databases at the amino acid level: (i) ENV_NR, a GenBank non-redundant protein database that includes many environmental datasets, (ii) an in-house database (SANGER_PEP) composed of proteins coded by Sanger-based viral metagenomic samples not represented in ENV_NR (Table 1), and (iii) ENV_NT, a collection of nucleotide sequences from metagenomic datasets deposited in GenBank. The purpose of these analyses is to determine how similar the viruses are within the query metagenomic samples to viruses and microbes that inhabit the different environments represented in the subject databases. The VMGAP reports all blast hits with e-values ≤1x10-3.

Table 1. Metagenomic libraries incorporated into the Sanger environmental protein database.

| Library Name | Reference |

|---|---|

| Viral metagenomes from Yellowstone hot springs (Bear Paw) | [32] |

| RNA viral community in human feces | [33] |

| viral metagenomes from yellowstone hot springs (Octopus) | [32] |

| Virus from Human Blood | [34] |

| Virus from Human Feces | [35] |

| Virus from Marine Sediments | [36] |

| Uncultured marine viral communities (Mission Bay) | [37] |

| Uncultured marine viral communities (Scripps Pier) | [37] |

| Coastal RNA virus communities | [38] |

| Chesapeake Bay virioplankton | [39] |

| Virus from equine feces | [40] |

4) HMM searches against PFAM/TIGRFAM and ACLAME HMM

In addition to similarity searches against protein databases, the VMGAP looks for the presence of HMMs from two databases, PFAM/TIGRFAM (a database of HMMs representing conserved protein domains) and ACLAME-HMMs (a compilation of HMMs that describe each of the protein families found in ACLAME). PFAM/TIGRFAM HMM searches are carried out in two different ways, either requiring a global or local alignment to the HMMs. Local HMM alignments increase sensitivity in the detection of conserved protein domains, particularly when the predicted peptide is truncated and extends to the end of the read, which is noted frequently in metagenomic datasets. All HMM hit with e-values ≤l1x10-5 are recorded for further analysis.

5) RPS-Blast against NCBI CDD database

The NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD) database is a collection of position specific scoring matrices representing conserved protein domains, protein families and superfamilies compiled from NCBI-curated domains [41], PFAM/TIGRFAM, SMART [42] and COG [43]. In spite of the overlap, PSSMs derived from PFAM/TIGRFAM do not behave exactly the same as their HMM counterparts, and in some cases these searches can identify domains where HMMs fail. The VMGAP stores all hits with e-values ≤ 1x10-5.

6) Identification of transmembrane domains and signal peptides

To discover transmembrane proteins and signal peptides that could be associated with the surface of viral particles, the VMGAP utilizes two programs, SignalP for the identification of signal peptides, and TMHMM, a program that detects candidate transmembrane domains.

7) Assignment of EC numbers

To aid in the metabolic reconstruction of metagenomes, the VMGAP makes use of PRIAM, a collection of PSSMs where each matrix represents an enzymatic function and is assigned to a particular EC number. Metagenomic samples are scanned for the presence of these PSSMs with RPS-Blast recording only those hits with e-values ≤1x10-10.

8) Rules hierarchy

Functional assignments of predicted peptides are carried out by retrieving the functional information produced from the results of the analyses performed in the previous steps following a series of pre-defined rules (Figure 1). Rules prioritize the use of a certain piece of evidence over another based on how informative, trustful and accurate that evidence is. As shown in Figure 1, hits against equivalog TIGRFAM HMMs [26]are the highest ranked supporting evidence for functional assignments in the VMGAP. Therefore, any protein that hits above the trusted cutoff of one entire copy (100% coverage with respect to the length of the HMM) of an equivalog TIGRFAM will automatically inherit the functional annotation associated to that particular HMM. The second and third tiers of evidence are constituted by highly significant BLASTP hits against ACLAME DB and the non-redundant protein database respectively; having at least 80% coverage (with respect to the shortest sequence), 50% identity and an e-value ≤ 1x10-10. Although proteins from ACLAME DB are also included in the non-redundant protein database, entries in the former have a higher priority since they are curated and therefore provide better functional annotation. Hits against HMMs describing ACLAME protein families and PFAM/non-equivalog TIGRFAM HMMs comprise the 4th and 5th layers of functional evidence, giving higher priority to those HMMs representing protein families against those describing conserved protein domains. Ranked 6th and 7th in the rule list are respectively RPS-BLAST hits with at least 90% coverage, percent identity ≥ 35% and e-value ≤ 1x10-10 against NCBI-CDD profiles and local-local hits against PFAM/TIGRFAM HMMs with e-values ≤ 1x10-5. Finally, low-confidence BLASTP hits with at least 70% coverage, percent identity ≥ 30% and e-value ≤ 1x10-5 against ACLAME DB and the non-redundant protein database occupy tiers 8 and 9 in the priority list respectively. Proteins that lack the evidence types described above, but still contain some other evidence such as hits against the environmental DBs are named “hypothetical protein”. Otherwise, proteins are labeled as “unknown protein”.

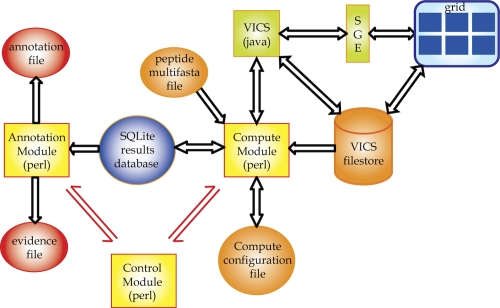

Implementation

The VMGAP consists of three major modules implemented in Perl (Figure 2): (i) the control module, which initializes the pipeline, creates a sqlite DB [44] to store the status of computations and their results, coordinates the other modules, and allows interrupted pipelines to be resumed from the point of interruption, (ii) the compute module, which tracks the status of the individual computations and loads completed computations into the sqlite database, and (iii) the annotation module, which reads the computational results from the sqlite DB and applies a set of predefined rules to generate a tab-delimited annotation file containing the final annotation for each peptide (e.g. EC/GO assignments and protein names), and a tab-delimited evidence file that stores all the evidence that supports the annotation. Each line in the annotation file contains the functional annotation for an individual peptide, while in the evidence file each line represents one particular evidence for a single protein (Table 2 and Table 3). Additionally, the VMGAP contains an optional module, also implemented in Perl, called Com2GO (Common-Name-to-Go Mappings). Com2GO can be run after the annotation module to attempt to classify the protein names using the GO hierarchy.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the implementation of the VMGAP. The three main modules of the pipeline are depicted by yellow squares. Orange and red circles represent input and output files respectively. VICS stands for Venter Institute Compute Services; SGE stands for Sun Grid Engine job scheduler. Single and double-headed arrows indicate information flowing in one or both directions respectively.

Table 2. Description of the contents of the evidence file generated by the VMGAP.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | CDD_RPS | Subject definition | % cov | % ident | e-value | % ident | ||

| ID | ALL GROUP_PEP | Subject ID | Subject definition | Query length | Subject length | % cov | % ident | e-value |

| ID | ACLAME_PEP | Subject ID | Subject definition | Query length | Subject length | % cov | % ident | e-value |

| ID | SANGER_PEP | Subject ID | Subject definition | Query length | Subject length | % cov | % ident | e-value |

| ID | ENV_NT | Subject ID | Subject definition | Query length | Subject length | % cov | % ident | e-value |

| ID | ENV_NR | Subject ID | Subject definition | Query length | Subject length | % cov | HMM description | e-value |

| ID | FRAG_HMM | HMM begin | HMM end | % cov | Total e-value |

HMM accession | HMM description | HMM length |

| ID | PFAM/TIGRFAM_HMM | HMM begin | HMM end | % cov | Total e-value |

HMM accession | HMM length | |

| ID | PRIAM | EC Number | e-value | HMM description | ||||

| ID | ACLAME_HMM | HMM begin | HMM end | % cov | Total e-value |

HMM accession | HMM length | |

| ID | PEPSTATS | Molecular weight | Isoelectric point | |||||

| ID | TMHMM | Number predicted helixes | ||||||

| ID | SIGNALP | signal pep | cleavage site position |

Fields 1 and 2 correspond to the protein identifier and a flag specific for each analysis, respectively. % cov, percent coverage; % ident, percent identity; CDD_RPS, RPS-Blast vs. CDD DB; ALLGROUP_PEP, Blastp vs. protein NR DB; ACLAME_PEP, Blastp vs. ACLAME protein DB; SANGER_PEP, Blastp vs. in-house viral metagenomic DB; ENV_NT, Tblastn vs. ENV_NT DB; ENV_NR, Blastp vs. ENV_NR DB; FRAG_HMM, HMM searches vs. local PFAM/TIGRFAM HMM DB; PFAM/TIGRFAM_HMM, HMM searches vs. global PFAM/TIGRFAM HMM DB; PRIAM, RPS-Blast vs. PRIAM profile DB; ACLAME_HMM, HMM searches vs. global ACLAME HMM DB; PEPSTATS, peptide statistics; TMHMM, transmembrane domain searches; SIGNALP, signal peptide searches.

Table 3. Explanation of the annotation file generated by the VMGAP.

| Column | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unique peptide ID | JCVI_PEP_metagenomic.orf.112038372243 2.1 |

| 2 | Protein common name tag | common_name |

| 3 | Functional description (s) | phosphonate C-P lyase system protein PhnL, putative |

| 4 | Source of functional description assignment | AllGroup High:rf|YP_001889651.1 |

| 5 | GO tag | GO |

| 6 | Gene Ontology ID (s) | go:0016887||go:0005524 |

| 7 | Source of Gene Ontology assignment | PF00005||PF00005 |

| 8 | EC tag | EC |

| 9 | Enzyme Commission number ID (s) | 3.6.3.28 |

| 10 | Source of Enzyme Commission ID | PRIAM |

| 11 | Hits against ENV_NT DB tag | ENV_NT |

| 12 | ENV_NT DB libraries hit with e-values ≤1 × 10-3 | Hydrothermal vent metagenome FOSS10958.y2, whole genome shotgun sequence || Lake Washington Formate SIP Enrichment Freshwater Metagenome || Human Gut Metagenome (healthy human sample In-M, Infant, Female) |

| 13 | Best hit e-value per environmental library | 6.65676e-54 || 2.14066e-44 || 1.34265e-46 |

| 14 | Number of hits with e-value ≤1 × 10-3 per environmental DB library | 1 || 1 || 4 |

| 15 | HMM DB tag | PFAM/TIGRFAM_HMM |

| 16 | PFAM/TIGRFAM HMM hit above trusted cutoff | PF000005 |

| 17 | Signalp tag | SIGNALP |

| 18 | Presence (Y) or absence (N) of predicted signal peptide | Y |

| 19 | Cleavage site position | 16 |

| 20 | Transmembrane domain tag | TMHMM |

| 21 | Number of predicted transmembrane domains | 2 |

| 22 | Protein statistics tag | PEPSTATS |

| 23 | Molecular weight | 17369.86 |

| 24 | Isoelectric point | 9.9423 |

Each lane contains the annotation for a single predicted peptide. Multiple values within a field are separated by the symbol “||”.

The heart of the VMGAP is the compute module (Figure 2). This module accepts a compute configuration file (see Table 4 for the current configuration) and a sqlite results database. It compares the computations specified in the configuration with the results loaded into the sqlite results database. Missing computations are initiated, stale computations (outdated reference dataset or obsolete program options) are refreshed, and interrupted computations are resumed. The computations themselves are executed either in a local machine (for jobs that are not very computational intensive such as SignalP), or through the JCVI high-throughput computing platform named VICS web-services. VICS is a J2EE server backed by a 1600 node SGE-grid and a 2 Terabyte scratch-disk. All of the computations are started (or restarted) and then the compute module waits for them to complete. As a computation is completed, its results are parsed and loaded into the sqlite database and the status of the computation is updated. When all computations have completed, the module exits and allows the controller to proceed. The module may be interrupted manually and restarted at a later time.

Table 4. List of programs and parameters in the VMGAP.

| Pipeline job name | Program | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| A CLAME_HMM | hmmpfam | E 0.001 |

| A CLAME_PEP | Blastp | b 50 -e 1e-5 |

| ALLGROUP_PEP | Blastp | b 50 -e 1e-5 |

| CDD_RPS | Rpsblast | b 50 -e 1e-3 |

| ENV_NR | blastp | b 50 -e 1e-3 |

| ENV_NT | tblastn | b 50 –e 1e-3 |

| FRAG_HMM | hmmpfam | E 0.001 |

| PEPSTATS | Pepstats | None |

| PFAM/TIGRFAM_HMM | Hmmpfam | E 0.001 |

| PRIAM | Priam | e 1e-10 |

| SANGER_PEP | Blastp | b 50 -e 1e-5 |

| SIGNALP | Signalp | t gram- -trunc 70 |

| TMHMM | tmhmm | None |

Data Visualization and Analysis

Small files can be easily imported and analyzed in Excel. For extremely large files (more than a million entries), we recommend users to import the data into METAREP [14] for further analysis and visualization. The METAREP tab-delimited import format specifies many common annotation data types including those computed by VMGAP. To import VMGAP annotations, we recommend the mapping outlined in (Table 5). To import the data, users have to install a local version of METAREP. The source code can be found at the METAPREP website [45]. The code also contains a Perl based utility for importing METAREP tab-delimited files. Details about the installation and import process can be found in the METAREP manual which can be downloaded from the METAPREP dashboard [46].

Table 5. VMGAP to METAREP mapping.

|

METAREP input file |

VGMAP |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Column | Field ID | Description | Description |

| 1 | peptide_ID | Unique peptide ID | Unique peptide ID |

| 2 | Library_ID | Library ID | Library ID |

| 3 | com_name | Functional description (s) | Common Names(s) |

| 4 | com_name_src | Source of functional description assignment | aNRdb BLAST + bFRAGHMM + PFAM + TIGRFAM + PRIAM + CDD +ACLAME |

| 5 | go_id | Gene Ontology ID (s) | Gene Ontology ID (s) |

| 6 | go_src | Source of Gene Ontology assignment | PFAM + TIGRFAM + ACLAME +Com2GO |

| 7 | ec_id | Enzyme Commission ID (s) | Enzyme Commission ID (s) |

| 8 | ec_src | Source of Enzyme Commission ID | TIGRFAM + PFAM + PRIAM |

| 9 | hmm_id | Hidden Markov Model hits | ACLAME, PFAM, TIGRFAM |

| 10 | blast_taxon | NCBI taxonomy ID | Best Blast Hit NRdb |

| 11 | blast_evalue | BLAST E-Value | Best Blast Hit NRdb |

| 12 | blast_pid | BLAST percent Identity | Best Blast Hit NRdb |

| 13 | blast_cov | BLAST sequence coverage of shortest sequence | Best Blast Hit NRdb |

| 14 | filter | Any filter tag (categorical variable) | N/A |

aJCVI non-redundant protein database; b, PFAM/TIGRFAM local-local alignment HMM database; c, data not available.

Discussion

In recent years and with the advancement of next generation sequencing platforms, metagenomic studies have become more affordable to the scientific community. This has triggered an exponential growth in the amount of metagenomic sequencing data available within public repositories and stresses the necessity for specialized highly efficient computational tools to cope with the functional annotation of these massive datasets. There are currently a variety of metagenomic annotation tools that are available to the general public through the web. Among the most popular resources is MG-RAST, an annotation tool that offers many advantages to the user: (i) it does not require a high-throughput computer facility, (ii) it uses reads instead of proteins as input and therefore there is no need for gene predictions, and (iii) the results are classified into functional categories facilitating the analysis of data. Perhaps most importantly, the functional distributions can be compared against other datasets that were annotated with MG-RAST.

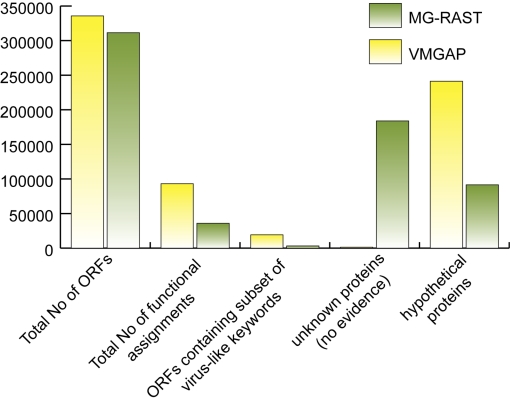

While MG-RAST is capable of providing meaningful taxonomic and functional annotation of microbial metagenomes, it is limited in its capacity to annotate viral metagenomes due to its inherent dependence of FIGfams. In order to quantitatively assess the utility of VMGAP for the functional annotation of viral metagenomic data, we ran an identical set of ~300,000 peptide sequences from a marine viral metagenomic library or their respective coding ORFs through the VMGAP and MG-RAST respectively. Analysis of the results showed that the VMGAP could assign functions to almost 16% more sequences compared to MG-RAST (names other than hypothetical or unknown, Figure 3). More specifically, when looking for viral-like enzymatic functions (e.g. integrase, endonuclease, DNA polymerase) or names describing viral-like structural functions (e.g. capsid, tail, neck, envelope), the VMGAP assigned almost 16,000 more viral-like names compared to MG-RAST. Of the sequences that received no functional names, ~72% contained some other evidence such as hits against environmental databases, PFAM domains or signal peptides while only 29% of such sequences are reported in MG-RAST (Figure3). A more in-depth analysis showed that the increase in assigned VMGAP-associated functional terms was due to the incorporation of databases that contain viral-specific annotation, such as ACLAME. Since VMGAP also performs additional analyses such as HMM, CDD and environmental DB searches as well as MeGO/GO and EC number assignments, it provides a more comprehensive repertoire of evidence types that may facilitate the discovery of novel viral functions as well as comparative analyses of metagenomic datasets.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of the functional annotation performance for viral libraries of the VMGAP compared with MG-RAST. Total number of functional assignments represents the amount of peptides from the viral library that gets a name other than “hypothetical protein” or “unknown” (VMGAP) or that does not have a significant hit against any FIGfam (MG-RAST). Unknown proteins are those that do not receive any evidence as described in Figure 1 (VMGAP) or that do not hit any FIGfams (MG-RAST). The following are examples of virus-like keywords used in this analysis: integrase, terminase, polymerase, recombinase, (endo|exo) nuclease, phage, viral, capsid, envelope, filament, and basal plate.

Regarding the VMGAP implementation, the generation and storage of results into a relational sqlite database presents many advantages over working with flat files. The sqlite database allows the pipeline to monitor the status of each process launched on the grid and, in case of failure, restart the pipeline from the point that it crashed. Also, it makes it easier to query results, integrate different data types when generating summary reports, and share this information since all the analysis data (i.e. programs, parameters, cutoffs) and their results are stored in a single sqlite file. The storage of data in an sqlite database, however, might present some loading speed challenges when the data volume is very large and the speed of the storage device where the database resides is not fast enough (e.g. 7,200 RPM SATA drives). At JCVI, sqlite databases typically reside in 15,000 RPM SAS drives, with bandwidths of ~ 500 MB/sec. For slower systems, we recommend avoiding the usage of these databases and rather parse the results directly from the raw outputs of the analyses to generate the annotation and evidence files.

The organizational format of the output tab-delimited files, annotation and evidence are also advantageous. Since the first column of these files contains unique protein identifiers, all of the annotation and supporting evidence for any protein or group of proteins can be retrieved using the Unix grep utility directly from the command line. These files can be also imported into Excel for their inspection and analysis. Lastly, the VMGAP pipeline can be easily updated and customized to meet the specific needs and objectives of the user through the addition of additional virus-specific databases as they become available or the inclusion of more specialized boutique databases (e.g. RNA virus specific datasets) respectively.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Office of Science (BER), U.S. Department of Energy, Cooperative Agreement No. De-FC02-02ER63453 and by the National Science Foundation Microbial Genome Sequencing Program (award number 0626826). We would like to thank Johannes Goll for his technical expertise on METAREP.

Abbreviations:

- VMGAP

ViralMetaGenome Annotation Pipeline

- rDNA

ribosomal DNA

- ORF

open reading frame

- EC

enzyme commission

- GO

gene ontology

- COG

cluster of orthologous genes

- DB

database

- HMM

Hidden Markov Model

- PSSM

position specific scoring matrix

References

- 1.Weinbauer MG. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2004; 28:127-181 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards RA, Rohwer F. Viral metagenomics. Nat Rev Microbiol 2005; 3:504-510 10.1038/nrmicro1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohwer F, Edwards R. The Phage Proteomic Tree: a genome-based taxonomy for phage. J Bacteriol 2002; 184:4529-4535 10.1128/JB.184.16.4529-4535.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, Fish J, Chai B, Farris RJ, Kulam AS, McGarrell DM, Marsh T, Garrity GM, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37(Database issue):D141-D145 10.1093/nar/gkn879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:5069-5072 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huson DH, Auch AF. QiJ, SchusterSC. MEGAN analysis of metagenomic data. Genome Res 2007; 17:377-386 10.1101/gr.5969107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsen FA, Kodner RB, Armbrust EV. pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:538 10.1186/1471-2105-11-538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Szeto E, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Dalevi D, Chen IM, Grechkin Y, Dubchak I, Anderson I, et al. IMG/M: a data management and analysis system for metagenomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36(Database issue):D534-D538 10.1093/nar/gkm869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun S, Chen J, Li W, Altintas I, Lin A, Peltier S, Stocks K, Allen EE, Ellisman M, Grethe J, et al. Community cyberinfrastructure for Advanced Microbial Ecology Research and Analysis: the CAMERA resource. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39(Database issue):D546-D551 10.1093/nar/gkq1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer F, Paarmann D, D'Souza M, Olson R, Glass EM, Kubal M, Paczian T, Rodriguez A, Stevens R, Wilke A, et al. The metagenomics RAST server - a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2008; 9:386 10.1186/1471-2105-9-386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye Y, Osterman A, Overbeek R, Godzik A. Automatic detection of subsystem/pathway variants in genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2005; 21(Suppl 1):i478-i486 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinsdale EA, Pantos O, Smriga S, Edwards RA, Angly F, Wegley L, Hatay M, Hall D, Brown E, Haynes M, et al. Microbial ecology of four coral atolls in the Northern Line Islands. PloS one 2008;3:e1584 10.1371/journal.pone.0001584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer F, Overbeek R, Rodriguez A. FIGfams: yet another set of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:6643-6654 10.1093/nar/gkp698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goll J, Rusch DB, Tanenbaum DM, Thiagarajan M, Li K, Methe BA, Yooseph S. METAREP: JCVI metagenomics reports--an open source tool for high-performance comparative metagenomics. Bioinformatics 2010; 26:2631-2632 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.HMMER http://hmmer.janelia.org

- 16.BLAST ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/release/LATEST/

- 17.Signal P.http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/cgi-bin/nph-sw_request?signalp

- 18.Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protoc 2007; 2:953-971 10.1038/nprot.2007.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.TMHMM. Transmembrane domain prediction. http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/cgi-bin/nph-sw_request?tmhmm

- 21.PRIAM http://priam.prabi.fr/REL_JUL06/index_jul06.html

- 22.Claudel-Renard C, Chevalet C, Faraut T, Kahn D. Enzyme-specific profiles for genome annotation: PRIAM. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31:6633-6639 10.1093/nar/gkg847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.UniProt-Consortium Ongoing and future developments at the Universal Protein Resource. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39(Database issue):D214-D219 10.1093/nar/gkq1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidsen T, Beck E, Ganapathy A, Montgomery R, Zafar N, Yang Q, Madupu R, Goetz P, Galinsky K, White O, et al. The comprehensive microbial resource. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38(Database issue):D340-D345 10.1093/nar/gkp912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, Gavin OL, Gunasekaran P, Ceric G, Forslund K, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38(Database issue):D211-D222 10.1093/nar/gkp985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selengut JD, Haft DH, Davidsen T, Ganapathy A. Gwinn-GiglioM, NelsonWC, RichterAR, WhiteO. TIGRFAMs and Genome Properties: tools for the assignment of molecular function and biological process in prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35(Database issue):D260-D264 10.1093/nar/gkl1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leplae R, Hebrant A, Wodak SJ, Toussaint A. ACLAME: a CLAssification of Mobile genetic Elements. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32(Database issue):D45-D49 10.1093/nar/gkh084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39(Database issue):D225-D229 10.1093/nar/gkq1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanenbaum DM, Goll J, Murphy S, Kumar P, Zafar N, Thiagarajan M, Madupu R, Davidsen T, Kagan L, Kravitz S, et al. The JCVI standard operating procedure for annotating prokaryotic 30. Noguchi H, Taniguchi T, Itoh T. MetaGeneAnnotator: detecting species-specific patterns of ribosomal binding site for precise gene prediction in anonymous prokaryotic and phage genomes. DNA Research 2008;15:387-396.metagenomic shotgun sequencing data. Stand Genomic Sci 2010; 2:229-237 10.4056/sigs.651139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noguchi H, Taniguchi T, Itoh T. MetaGeneAnnotator: detecting species-specific patterns of ribosomal binding site for precise gene prediction in anonymous prokaryotic and phage genomes. DNA Res 2008; 15:387-396 10.1093/dnares/dsn027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MetaGeneAnnotator http://metagene.cb.k.u-tokyo.ac.jp/metagene/download_mga.html

- 32.Schoenfeld T, Patterson M, Richardson PM, Wommack KE, Young M, Mead D. Assembly of viral metagenomes from yellowstone hot springs. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008; 74:4164-4174 10.1128/AEM.02598-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang T, Breitbart M, Lee WH, Run JQ, Wei CL, Soh SW, Hibberd ML, Liu ET, Rohwer F, Ruan Y. RNA viral community in human feces: prevalence of plant pathogenic viruses. PLoS Biol 2006; 4:e3 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breitbart M, Rohwer F. Method for discovering novel DNA viruses in blood using viral particle selection and shotgun sequencing. Biotechniques 2005; 39:729-736 10.2144/000112019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breitbart M, Haynes M, Kelley S, Angly F, Edwards RA, Felts B, Mahaffy JM, Mueller J, Nulton J, Rayhawk S, et al. Viral diversity and dynamics in an infant gut. Res Microbiol 2008; 159:367-373 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breitbart M, Felts B, Kelley S, Mahaffy JM, Nulton J, Salamon P, Rohwer F. Diversity and population structure of a near-shore marine-sediment viral community. Proc Biol Sci 2004; 271:565-574 10.1098/rspb.2003.2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breitbart M, Salamon P, Andresen B, Mahaffy JM, Segall AM, Mead D, Azam F, Rohwer F. Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99:14250-14255 10.1073/pnas.202488399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culley AI, Lang AS, Suttle CA. Metagenomic analysis of coastal RNA virus communities. Science 2006; 312:1795-1798 10.1126/science.1127404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bench SR, Hanson TE, Williamson KE, Ghosh D, Radosovich M, Wang K, Wommack KE. Metagenomic characterization of Chesapeake Bay virioplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007; 73:7629-7641 10.1128/AEM.00938-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cann AJ, Fandrich SE, Heaphy S. Analysis of the virus population present in equine faeces indicates the presence of hundreds of uncharacterized virus genomes. Virus Genes 2005; 30:151-156 10.1007/s11262-004-5624-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, Dicuccio M, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38(Database issue):D5-D16 10.1093/nar/gkp967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Letunic I, Copley RR, Pils B, Pinkert S, Schultz J, Bork P. SMART 5: domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res 2006; 34(Database issue):D257-D260 10.1093/nar/gkj079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, Krylov DM, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskaya AN, et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 2003; 4:41 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.SQLite software library http://www.sqlite.org

- 45.METAREP. JCVI Metagenomics Reports - an open source tool for high-performance comparative metagenomics. https://github.com/jcvi/METAREP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.METAREP. JCVI Metagenomics Reports. http://www.jcvi.org/metarep