Abstract

Tsukamurella paurometabola corrig. (Steinhaus 1941) Collins et al. 1988 is the type species of the genus Tsukamurella, which is the type genus to the family Tsukamurellaceae. The species is not only of interest because of its isolated phylogenetic location, but also because it is a human opportunistic pathogen with some strains of the species reported to cause lung infection, lethal meningitis, and necrotizing tenosynovitis. This is the first completed genome sequence of a member of the genus Tsukamurella and the first genome sequence of a member of the family Tsukamurellaceae. The 4,479,724 bp long genome contains a 99,806 bp long plasmid and a total of 4,335 protein-coding and 56 RNA genes, and is a part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: obligately aerobic, non-motile, mesophilic, chemoorganotrophic, Gram-positive, metachromatic granules, opportunistic pathogen, Tsukamurellaceae, GEBA

Introduction

Strain no. 33T (= DSM 20162 = ATCC 8368 = JCM 10117) is the type strain of the species Tsukamurella paurometabola, which in turn is the type species of the genus Tsukamurella [1,2]. Currently, there are eleven species within the genus Tsukamurella [1,3], which is named in honor of Michio Tsukamura, a Japanese microbiologist [1]. The species epithet derives from the Greek words paurus meaning little and metabolus meaning changeable, referring to a metabolism that is little changeable [1]. Strain no. 33T was first isolated from the mycetome and ovaries of Cimex lectularis (bedbug) in a study on the bacterial flora of Hexapoda by Edward A. Steinhaus in 1941 [2]. T. paurometabola was formerly also known as Corynebacterium paurometabolum (basonym) [1,4] as well as under its heterotypic synonym Rhodococcus aurantiacus [5,6], until Collins et al. revised the controversial taxonomic position of the species in 1988 [1] and J. P. Euzéby corrected the species epithet according to the rules of to the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (1990 Revision) [7]. T. paurometabola is known, albeit rarely, to be an opportunistic pathogen for humans, especially in patients with predisposing conditions, such as immunosuppression (leukemia, solid tumors, and HIV infection) [8,9], chronic lung disease (tuberculosis) [9], and most often indwelling foreign bodies (long-term use of indwelling catheters) [10-13]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for T. paurometabola no. 33T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

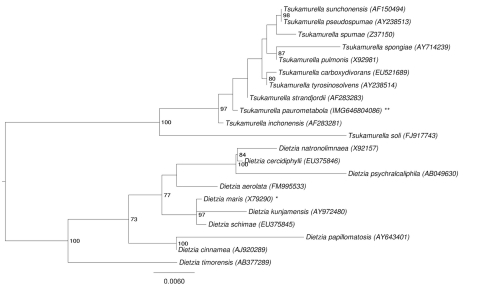

The phylogenetic neighborhood of T. paurometabola no. 33T in a 16S rRNA based tree is shown in Figure 1. The sequences of the two identical 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome differ by one nucleotide from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence (AF283280).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of T. paurometabola relative to the other type strains within the genus Tsukamurella. The tree was inferred from 1,447 aligned characters [14,15] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [16] and rooted with the members of the closely related genus Dietzia. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates [17] if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [18] are labeled with one asterisk, those registered as 'Complete and Published' with two asterisks.

A representative genomic 16S rRNA sequence of strain no. 33T was compared using NCBI BLAST under default settings (e.g., considering only the high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) from the best 250 hits) with the most recent release of the Greengenes database [19] and the relative frequencies, of taxa and keywords (reduced to their stem [20]) were determined, weighted by BLAST scores. The most frequently occurring genera were Tsukamurella (34.7%), Mycobacterium (32.5%), Dietzia (20.6%) and Rhodococcus (12.1%) (220 hits in total). Regarding the seven hits to sequences from members of the species, the average identity within HSPs was 99.3%, whereas the average coverage by HSPs was 96.7%. Regarding the 45 hits to sequences from other members of the genus, the average identity within HSPs was 99.2%, whereas the average coverage by HSPs was 96.2%. Among all other species, the one yielding the highest score was Tsukamurella strandjordii, (NR_025113), which corresponded to an identity of 99.5% and a HSP coverage of 100.0%. (Note that the Greengenes database uses the INSDC (= EMBL/NCBI/DDBJ) annotation, which is not an authoritative source for nomenclature or classification.) The highest-scoring environmental sequence was DQ366095 ('on Oil Degrading Consortium oil polluted soil clone MH1 Pitesti'), which showed an identity of 99.2% and an HSP coverage of 99.0%. The most frequently occurring keywords within the labels of environmental samples which yielded hits were 'skin' (9.6%), 'human' (4.8%), 'microbiom, tempor, topograph' (4.2%), 'sea' (3.8%) and 'sediment' (1.8%) (30 hits in total). Environmental samples which yielded hits of a higher score than the highest scoring species were not found. These environmental labels are in line with the locations reported for the isolation of Tsukamurella strains, such as soil, human sputum, and bed bug [2,21].

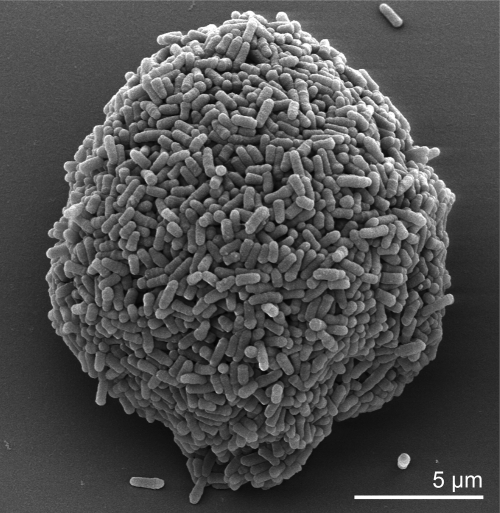

The cells of T. paurometabola are straight to slightly curved rods with a size of 0.5-0.8 × 1.0-5 µm and occur singly, in pairs, or in masses [2,21] (Figure 2). The organism is Gram-positive, weakly acid-fast (some strains are strongly acid-fast), non-sporeforming and non-motile [2,21] (Table 1). The organism contains metachromatic granules [2]. Colonies of T. paurometabola are small (diameter, 0.5-2.0 mm) with convex elevation, have entire edges (sometimes rhizoidal), are dryish but easily emulsified and are white to creamy to orange in color [3.15]. T. paurometabola is strictly aerobic and chemoorganotrophic bacterium [1]. Reaction is positive for catalase and pyrazinamidase [1]. Acid is produced from some sugars [1]. The organism does not produce nitriles from nitrates [2]. Indole is not produced by T. paurometabola [2]. The organism is non-pathogenic for guinea pigs [2]. In general T. paurometabola strains grow in the range 10°C to 35°C. Strain no. 33T does not grow at 45°C [1]. The strain did not survive heating at 60°C for 15 minutes [1]. Some strains of T. paurometabola produce acid from fructose, galactose, glucose, glycerol, inositol, manitol, mannose, sorbitol, sucrose, and trehalose [1]. Acid is not produced from L-arabinose, L-rhamnose, or D-xylose [1]. Some strains of T. paurometabola grow on ethanol, fructose, galactose, glucose, inositol, mannitol, mannose, melizitose, sorbitol, sucrose, trehalose, xylose, n-butanol, isobutanol, 2,3-butylene glycol, propanol, propylene glycol, citrate, fumarate, malate, pyruvate, and succinate [1]. The organism does not grow on adonitol, arabinose, inulin, lactose, raffinose, or rhamnose [1]. Acetamide and nicotinamide are used as sole nitrogen sources but not benzamide [1]. Acetamide, glutamate, glucosamine, monoethanolamine, and serine are used as sole sources of carbon and nitrogen [1]. T. paurometabola is able to degrade Tween 20, Tween 40, Tween 60, and Tween 80, but not adenine, casein, or elastin [1]. Some strains of T. paurometabolum degrade xanthine and tyrosine [1]. The organism produces β-galactosidase and urease, but not arylsulfatase or α-esterase [1]. T. paurometabolum is resistant to ethambutol (5 µg/ml), 5-fluorouracil (20 µg/ml), mitomycin C (10 µg/ml), and picric acid (0.2% w/v) [1]. The organism is susceptible to bleomycin (5 µg/ml) [1].

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of T. paurometabola no. 33T

Table 1. Classification and general features of T. paurometabola no. 33T according to the MIGS recommendations [22] and the NamesforLife database [23].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [24] | |

| Phylum “Actinobacteria” | TAS [25] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [26] | ||

| Subclass Actinobacteridae | TAS [26,27] | ||

| Order Actinomycetales | TAS [26-29] | ||

| Suborder Corynebacterineae | TAS [26,27] | ||

| Family Tsukamurellaceae | TAS [26,27] | ||

| Genus Tsukamurella | TAS [1] | ||

| Species Tsukamurella paurometabola | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain no. 33 | TAS [2] | ||

| Gram stain | positive | TAS [2] | |

| Cell shape | short rods occurring singly, in pairs or in masses | TAS [2] | |

| Motility | none | TAS [2] | |

| Sporulation | none | TAS [2] | |

| Temperature range | 10°C–35°C, not at 45°C | NAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | not reported | ||

| Salinity | not reported | ||

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | obligately aerobic | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | carbohydrates | TAS [1] | |

| Energy metabolism | chemoorganotroph | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | soil, human sputum, insect microbiome | TAS [2,4] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free-living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | infection of the lung, lethal meningitis, and necrotizing tenosynovitis |

TAS [4] |

| Biosafety level | 1+ | TAS [30] | |

| Isolation | ovaries of Cimex lectularius (bedbug) | TAS [2,4] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | most probably close to Columbus, Ohio | NAS |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1941 or before | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [31]. If the evidence code is IDA, the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Chemotaxonomy

The major cell wall sugars of T. paurometabola are arabinose and galactose [1], but ribose and traces of glucose have also been observed (unpublished data, DSMZ). The diagnostic amino acid of peptidoglycan is meso-diaminopimelic acid (variation A1γ); the glycan moiety of cell walls contains N-glycolyl residues [1]. Arabinogalactan is covalently attached to the peptidoglycan [32]. Long-chain highly unsaturated mycolic acids (62 to 78 carbon atoms) are present and contain one to six double bonds [1]. Fatty acid esters released on pyrolysis of mycolic acids have 20 to 22 carbon atoms [1,21]. The major polar lipids of T. paurometabola are diphosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, and mono- and diacylated phosphatidylinositol dimannosides [1,21]. Some strains of T. paurometabola produce glycolipids [1]. The long-chain cellular fatty acids are predominantly straight-chain saturated, mono-unsaturated, and 10-methyl branched acids [1]. Menaquinones are the sole respiratory quinones, with MK-9 predominating [1]: 80% MK-9 (H0), 6.8% MK-8 (H0), 3.5% MK-7 (H0), 2.3%.MK-10 (H0) and 6.7%.MK-8 (H2) (unpublished data, DSMZ).

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position [33], and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [34]. The genome project is deposited in the Genome On Line Database [18] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three genomic libraries: Sanger 8 kb pMCL200 library, 40 kb (fosmid, pcc1Fos) library, 454 pyrosequence standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 8.25 × Sanger; 37.9 × pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 1.1.02.15, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP001966 (chromosome) CP001967 (plasmid Tpau01) |

|

| Genbank Date of Release | May 17, 2010 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01341 | |

| NCBI project ID | 29399 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 646564587 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 20162 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

T. paurometabola no. 33T, DSM 2016, was grown in medium 535 (Trypticase soy broth medium) [35] at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using MasterPure Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre MGP04100) following the standard protocol as recommended by the manufacturer, with modification st/LALMice for cell lysis as described in [24]. DNA is available through the DNA Bank Network [36].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at the JGI website [37]. Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into 4,920 overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using the parallel phrap assembler [38]. Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher or transposon bombing of bridging clones [39]. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification. A total of 516 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together, the combination of the Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms provided 46.15 × coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 42,170 Sanger reads and 745,985 pyrosequencing reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [40] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [41]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant database, UniProt, TIGR-Fam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes - Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [42].

Genome properties

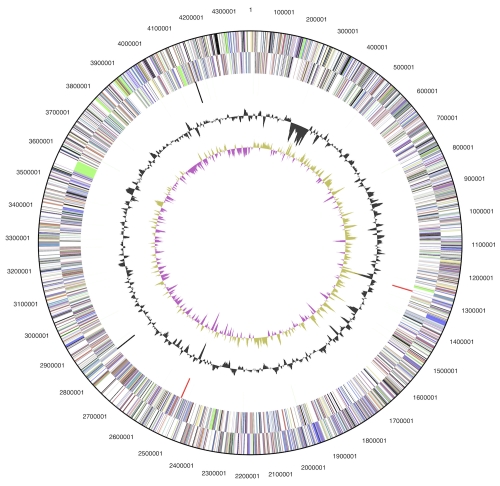

The genome consists of a 4,379,918 bp long chromosome and a 99,806 bp long plasmid, both with a G+C content of 68.4% (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 4,391 genes predicted, 4,335 were protein-coding genes, and 56 RNAs; 93 pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (68.7%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,479,724 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 4,108,044 | 91.70% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 3,064,083 | 68.40% |

| Number of replicons | 2 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 1 | |

| Total genes | 4,391 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 56 | 1.28% |

| rRNA operons | 2 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 4,335 | 98.72% |

| Pseudo genes | 93 | 2.12% |

| Genes with function prediction | 3,017 | 68.71% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 691 | 15.74% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,025 | 68.89% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 3,376 | 76.88% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,031 | 23.48% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,114 | 25.37% |

| CRISPR repeats | N.D. |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 169 | 5.0 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 310 | 9.2 | Transcription |

| L | 198 | 5.9 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 31 | 0.9 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 39 | 1.2 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 131 | 3.9 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 135 | 4.0 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 3 | 0.1 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 29 | 0.9 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 102 | 3.0 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 217 | 6.4 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 220 | 6.5 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 274 | 8.1 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 85 | 2.5 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 165 | 4.9 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 231 | 6.8 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 169 | 5.0 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 172 | 5.1 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 430 | 12.7 | General function prediction only |

| S | 269 | 8.0 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,366 | 31.1 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Marlen Jando (DSMZ) for growing cultures of T. paurometabola. This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, UT-Battelle and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1 and Thailand Research Fund Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program No. PHD/0019/2548 for MY.

References

- 1.Collins MD, Smida J, Dorsch M, Stackebrandt E. Tsukamurella gen. nov. harboring Corynebacterium paurometabolum and Rhodococcus aurantiacus. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1988; 38:385-391 10.1099/00207713-38-4-385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinhaus EA. A study of the bacteria associated with thirty species of insects. J Bacteriol 1941; 42:757-790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Euzéby JP. List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590-592 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins MD, Cummins CS. Genus Corynebacterium Lehmann and Neumann 1896. In: Sneath PHA, Mair NS, Sharpe ME, Holt JG (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Gram-positive Bacteria other than Actinomycetales, 1st Edition, Volume 2, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1986, p. 1275. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukamura M, Mizuna S. A new species, Gordonia aurantiaca, occuring in sputa of patients with pulmonary disease. [in Japanese]. Kekkaku 1971; 46:93-98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukamura M, Yano I. Rhodococcus sputi sp. nov., nom. rev., and Rhodococcus aurantiacus sp. nov., nom. rev. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1985; 35:364-368 10.1099/00207713-35-3-364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Euzéby JP. Taxonomic note: necessary correction of specific and subspecific epithets according to Rules 12c and 13b of the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (1990 Revision). Int J Syst Bacteriol 1998; 48:1073-1075 10.1099/00207713-48-3-1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz MA, Tabet SR, Collier AC, Wallis CK, Carlson LC, Nguyen TT, Kattar MM, Coyle MB. Central venous catheter-related bacteremia due to Tsukamurella species in the immunocompromised host: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:e72-e77 10.1086/342561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rey D, Fraisse P, Riegel P, Piemont Y, Lang JM. Tsukamurella infections. Review of the literature apropos of a case. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1997; 45:60-65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro CL, Haft RF, Gantz NM, Doern GV, Christenson JC, O’Brien R, Overall JC, Brown BA, Eallace RJ., Jr Tsukamurella paurometabola: a novel pathogen causing catheter-related bacteremia in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis 1992; 14:200-203 10.1093/clinids/14.1.200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai KK. A cancer patient with central venous catheter-related sepsis caused by Tsukamurella paurometabolum (Gordona aurantiaca). Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17:285-287 10.1093/clinids/17.2.285-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones RS, Fekete T, Truant AL, Satishchandran V. Persistent bacteremia due to Tsukamurella paurometabolum in a patient undergoing hemodialysis: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 18:830-832 10.1093/clinids/18.5.830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouza E, Pérez-Parra A, Rosal M, Martín-Rabadán P, Rodríguez-Créixems M, Marín M. Tsukamurella: a cause of catheter-related bloodstream infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2009; 28:203-210 10.1007/s10096-008-0607-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie E, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen G. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:5069-5072 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porter MF. An algorithm for suffix stripping. Program: electronic library and information systems. 1980; 14:130-137.

- 21.Group 22, Nocardioform Actinomycetes, Genus Tsukamurella. In: Holt JG, Krieg NR, Sneath PHA, Staley JT, Williams ST (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, 9th Edition, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1994, p. 627. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrity G. NamesforLife. BrowserTool takes expertise out of the database and puts it right in the browser. Microbiol Today 2010; 37:9 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The road map to the Manual, In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz R (eds), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2 ed, vol. 1. Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119–169. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of the bacteria II. The primary subdivisions of the schizomycetes. J Bacteriol 1917; 2:155-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.BAuA. 2010. Classification of bacteria and archaea in risk groups. TRBA 466 p. 187.

- 31.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tropis M, Lemassu A, Vincent V, Daffé M. Structural elucidation of the predominant motifs of the major cell wall arabinogalactan antigens from the borderline species Tsukamurella paurometabolum and Mycobacterium fallax. Glycobiology 2005; 15:677-686 10.1093/glycob/cwi052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klenk HP, Göker M. En route to a genome-based classification of Archaea and Bacteria? Syst Appl Microbiol 2010; 33:175-182 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.List of growth media used at DSMZ:http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 36.Gemeinholzer B, Dröge G, Zetzsche H, Haszprunar G, Klenk HP, Güntsch A, Berendsohn WG, Wägele JW. The DNA Bank Network: the start from a German initiative. Biopreservation and Biobanking 2011; 9:51-55 10.1089/bio.2010.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.JGI website. http://www.jgi.doe.gov/

- 38.The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package. http://www.phrap.com

- 39.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter J, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyatt D, Chen GL, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pati A, Ivanova NN, Mikhailova N, Ovchinnikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: a gene prediction improvement pipeline for prokaryotic genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Markowitz VM, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]