CASE LETTER

To the Editor: Distinction between primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and systemic ALCL is important due to differences in clinical behavior, treatment, and prognosis.1 Primary cutaneous ALCL (PCALCL) is defined as the absence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis.1 Translocations involving the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene detected by immunohistochemistry as positive staining with antibodies against ALK or fluorescent in situ hybridization are observed in 50 to 80% of systemic ALCL cases but are rare in PCALCL.2, 3 Therefore, ALK positivity in ALCL suggests the probability of systemic involvement, i.e. systemic ALCL. We present a case of ALK+ PCALCL with eventual systemic involvement.

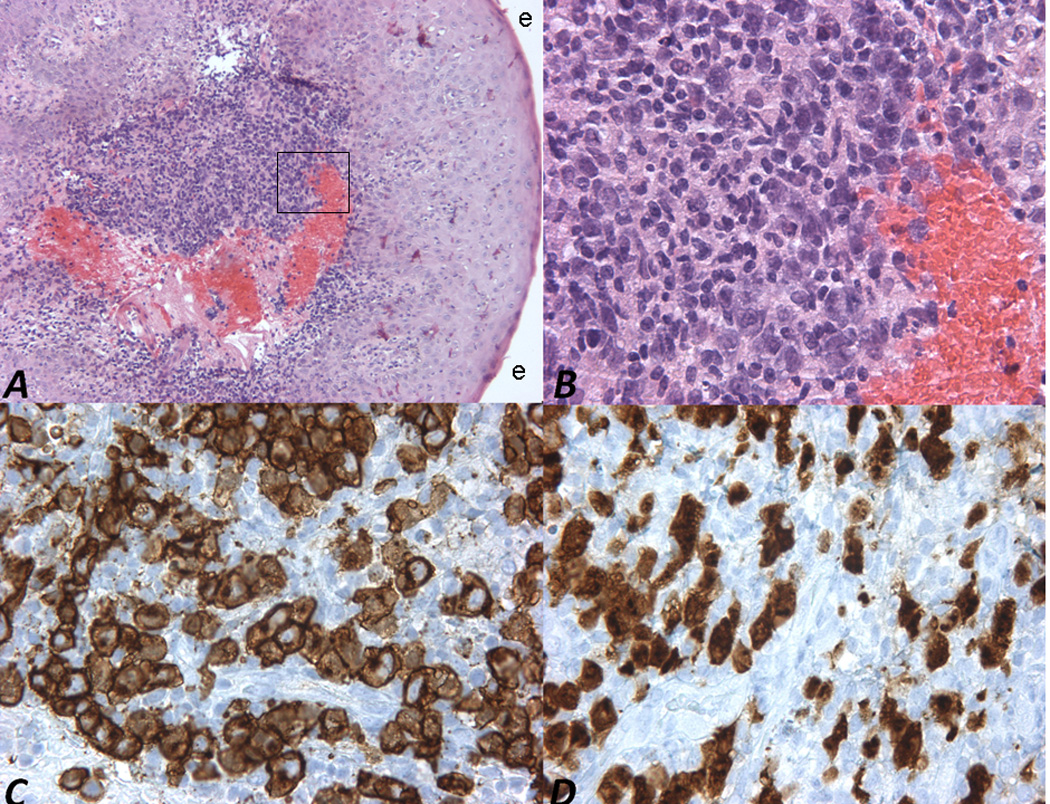

A 33 year old man presented with a 2.5 cm right postauricular and smaller right axillary and lower leg nodules. Biopsies were consistent with ALCL (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry revealed nuclear and cytoplasmic ALK staining. Fluorescent in situ hybridization confirmed an ALK translocation. T cell receptor gene rearrangement studies revealed monoclonality. A bone marrow biopsy and computed tomography (CT) scan were unremarkable.

Figure 1.

A & B) H & E stained sections show pleomorphic cells with enlarged nuclei, medium sized nucleoli, hyperchromasia and moderate cytoplasm, 10× and 40×, respectively. The box in Figure 1A denotes the approximate location of the high powered field magnifications in figures 1B through 1D. Overlying epidermis (e) is also depicted. C) The cells stain strongly with antibodies against CD30. D) The atypical cells also stain strongly with antibodies against ALK-1.

He received six cycles of cyclophosphamide, hydroxydoxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone over a five month period resulting in complete response. Four months later, he developed a biopsy-proven left upper arm ALCL nodule, which responded completely to four cycles of ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) and localized radiation therapy. One year later, he presented with another biopsy-proven ALCL nodule on his lower back (Figure 2), which was excised without recurrence. Two months later, biopsy of a 5.8 × 4.5 cm painful, necrotic, left lower intra-abdominal mass confirmed systemic ALCL. He received three additional cycles of ICE chemotherapy, consolidative radiation therapy, and autologous stem cell transplantation with reduction in the mass’s size. He again underwent radiation treatment to the same area three months later for positron emission tomography (PET) positive uptake. He has been in complete remission for at least seven months.

Figure 2.

1.0 × 1.4 × 0.4 cm erythematous nodule on the patient’s left back.

PCALCL has a 97.5% five year survival rate, whereas systemic spread decreases survival to 58.3%.2 Our patient developed systemic lesions approximately two years following diagnosis, suggesting that ALK+ PCALCL follows a more aggressive course. Limited early systemic disease and initial chemotherapy may have masked early systemic involvement.

The most common ALK mutation in ALCL results from a t(2;5)(p23;q35), fusing the ALK kinase domain coding region with the N-terminal portion of the nucleophosmin (NPM) gene, resulting in the constitutively expressed fusion protein NPM-ALK.3 Our patient had both nuclear and cytoplasmic ALK staining, which is unusual in PCALCL.3 Other reported cases of ALK+ PCALCL had only cytoplasmic staining, no NPM-ALK translocation, and were more indolent.4 This suggests that different types of ALK mutations confer different prognoses in PCALCL. For ALK+ PCALCL cases, we recommend baseline CT and PET scans followed by a history, physical examination, and, for PET-avid disease (94% of lymphomas), PET scans, every 3 months for the first 2 years, every 6 months for the next 3 years, and annually thereafter in accordance with recommendations of NCI-sponsored international workshops.5 For PET negative ALCL, more judicious use of CT scans as clinically indicated may be employed.

Acknowledgments

D.C. was supported in part by NIH T32 Grant #AR007569 awarded to K.D.C., and M.T. was supported in part by a Dermatology Foundation Dermatologist Investigator Research Fellowship awarded to M.T.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ALCL

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- PCALCL

Primary cutaneous ALCL

- ALK

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- CT

Computerized tomography

- ICE

Ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- NPM-ALK

Nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768–3785. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vergier B, Beylot-Barry M, Pulford K, Michel P, Bosq J, de Muret A, et al. Statistical evaluation of diagnostic and prognostic features of CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathologic study of 65 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1192–1202. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medeiros LJ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS. Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:707–722. doi: 10.1309/r2q9ccuvtlrycf3h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadin ME, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Duran IH, Fuller CE, Onciu M, et al. Primary Cutaneous ALCL With Phosphorylated/Activated Cytoplasmic ALK and Novel Phenotype: EMA/MUC1+, Cutaneous Lymphocyte Antigen Negative. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2008;32:1421–1426. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181648d6d. 10.097/PAS.0b013e3181648d6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, et al. Revised Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]