Abstract

Summary

Background and objectives

Children with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at risk for cognitive dysfunction, and over half have hypertension. Data on the potential contribution of hypertension to CKD-associated neurocognitive deficits in children are limited. Our objective was to determine whether children with CKD and elevated BP (EBP) had decreased performance on neurocognitive testing compared with children with CKD and normal BP.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This was a cross-sectional analysis of the relation between auscultatory BP and neurocognitive test performance in children 6 to 17 years enrolled in the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) project.

Results

Of 383 subjects, 132 (34%) had EBP (systolic BP and/or diastolic BP ≥90th percentile). Subjects with EBP had lower mean (SD) scores on Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence (WASI) Performance IQ than those with normal BP (normal BP versus EBP, 96.1 (16.7) versus 92.4 (14.9), P = 0.03) and WASI Full Scale IQ (97.0 (16.2) versus 93.4 (16.5), P = 0.04). BP index (subject's BP/95th percentile BP) correlated inversely with Performance IQ score (systolic, r = −0.13, P = 0.01; diastolic, r = −0.19, P < 0.001). On multivariate analysis, the association between lower Performance IQ score and increased BP remained significant after controlling for demographic and disease-related variables (EBP, β = −3.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −7.3 to −0.06; systolic BP index, β = −1.16 to 95% CI: −2.1, −0.21; diastolic BP index, β = −1.17, 95% CI: −1.8 to −0.55).

Conclusions

Higher BP was independently associated with decreased WASI Performance IQ scores in children with mild-to-moderate CKD.

Introduction

Children with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at risk for cognitive dysfunction (1,2). Although advances such as improved nutrition, avoidance of aluminum, improved dialysis, and improved anemia control have significantly decreased the prevalence of severe developmental delay, studies continue to show that children with CKD demonstrate deficits on neurocognitive testing as well as academic achievement that is significantly below grade level in comparison with healthy children (3). Previous studies have focused primarily on children with end-stage kidney disease or severe CKD with little data available on the neurocognitive function of children with mild-to-moderate CKD (1). However, the ongoing Children with Chronic Kidney Disease Cohort Study (CKiD) is currently evaluating neurocognitive function in nearly 540 children with mild-to-moderate CKD (4). A recent report of the baseline neurocognitive function of the cohort revealed that, although children with mild-to-moderate CKD did not demonstrate major neurocognitive deficits, a substantial proportion did show neurocognitive dysfunction, particularly in the form of lower ratings of executive functions (5).

The etiology of neurocognitive dysfunction in children with CKD is likely multifactorial and may include effects of the renal disease itself as well as effects of associated comorbidities such as anemia, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension (1). Over half of children with CKD are hypertensive (6,7). It is known that young adults with primary hypertension demonstrate decreased performance on neurocognitive testing compared with normotensive controls (8). There is emerging evidence that children with primary hypertension also have decreased performance on neurocognitive testing (9). However, data on the potential contribution of hypertension to CKD-associated neurocognitive deficits in children are limited, particularly in those with mild-to-moderate CKD.

In this report, neurocognitive data from the CKiD study were analyzed to determine whether children with CKD and increased BP have decreased performance on selected neurocognitive functions when compared with children with CKD and normal BP. In addition, the relative contribution of BP to neurocognitive outcomes, when controlling for selected sociodemographic and disease-related variables, was examined.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

The CKiD study is a longitudinal, observational cohort study of children with CKD being conducted at 46 pediatric nephrology centers in North America. Enrollment criteria include age 1 to 16 years and Schwartz-estimated GFR of 30 to 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, whereas exclusion criteria include solid organ, bone marrow, or stem cell transplant; dialysis treatment within 3 months before enrollment; cancer/leukemia or HIV treatment within the past year; pregnancy within the past year; inability to complete protocol procedures; or enrollment in a randomized clinical trial with masked treatment. This study is a cross-sectional analysis of baseline information for CKiD subjects between the ages of 6 and 17 years for whom both neurocognitive data and BP measurements were available as of September 2009. Subjects younger than 6 years were administered a different neurocognitive test battery and were therefore excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each participating center.

Measurements

Blood Pressure Measurement

As part of the study protocol, CKiD participants have casual BP measurements obtained in the right arm by auscultation at each study visit (6). Three BP measurements are obtained by auscultation of the brachial artery using the first Korotkoff sound for systolic BP (SBP) and the fifth Korotkoff sound for diastolic BP (DBP). The average of the three BP measurements are recorded as the participant's BP for the study visit. BP obtained at the CKiD study visit corresponding with the initial neurocognitive assessment (6 months after the baseline study visit) were included in this study.

If the SBP and DBP were both <90th percentile for age, gender, and height (10), the subject was categorized as having normal BP. If the SBP and/or DBP were ≥90th percentile, then the subject was categorized as having elevated BP (EBP). Categorization of subjects as having normal BP or EBP was made regardless of whether the subject was reported to be on antihypertensive medication. Subjects with EBP were considered to be prehypertensive if the SBP and/or DBP was ≥90th percentile but both <95th percentile. Subjects with either SBP or DBP ≥95th percentile were considered hypertensive (10). For analysis of BP as a continuous variable, BP index, defined as the subject's BP divided by the 95th percentile BP for that subject's gender, age, and height, was calculated (10). Normal BP values in children change with growth, with older and taller children having higher normal values compared with younger and shorter children. In addition, boys tend to have higher normal BP ranges than girls. Using BP index instead of absolute BP values allows standardized comparison of children's BP across the spectrum of age, gender, and height.

Neurocognitive Assessment

In CKiD, neurocognitive assessment is performed 6 months after study entry and every 2 years thereafter (4). Measurements from the first neurocognitive assessment were analyzed in this study and included age-specific measures of intellectual functioning (Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence [WASI]), basic academic achievement (Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-II-Abbreviated [WIAT-II-A]), attention regulation (Conners' Continuous Performance Test-II [CPT-II]), and ratings of executive functioning (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions [Parent BRIEF]). Order effects were controlled via counterbalancing blocks of tasks. All of the assessments were administered/supervised at each participating clinical site by a licensed psychologist who was not aware of the subject's BP status. To ensure quality control, neurocognitive data for the first two cases completed at each clinical site were reviewed by the Clinical Coordinating Center neuropsychologist. Thereafter, 25% of the assessments were reviewed to verify administration fidelity, scoring accuracy, accuracy of translation of raw scores into standardized scores, and accuracy of transcription of the scores onto the case report forms. All of the measures in the neurocognitive battery have very good to excellent ratings of reliability (11).

Other Variables

GFR was determined by plasma iohexol disappearance (iGFR) (12). Demographic and medical history data were collected using standardized forms. Variables of interest for this analysis included age, gender, maternal education (high school or less, 13 to 15 years of education, or ≥16 years of education), self-reported race (African American versus non–African American), and ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic), body mass index (BMI) percentile, duration of CKD (% of life with CKD, defined as CKD duration/age * 100), reported use of antihypertensive medications, and low birth weight (LBW, <2500 g).

Data Analyses

The data in this report are reported as the means ± SD, median with interquartile range, or frequencies and percentages, as appropriate. Initial group differences were examined to determine potential variables that could be used as covariates. Here, continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and proportions were compared using the Fisher exact test. To determine whether children with CKD and EBP have poorer performance in neurocognitive function when compared with CKD children with normal BP, the normal BP and EBP groups were compared using unequal variance t tests that are robust to non-normality. To assess the association between BP level and neurocognitive performance, multiple linear regressions were performed for the neurocognitive measures found to be different between the BP groups. Each regression included an analysis of residuals as a check on the required assumptions of normally distributed errors with constant variance. If these assumptions were violated, data transformations were used. Separate analyses investigated the strength of the relationship between neurocognition and BP defined as a categorical variable as well as a continuous variable. In addition to BP, other independent variables in the regression models included sociodemographic variables (i.e., gender, age, race, ethnicity, and maternal education) and disease-related variables (i.e., BMI percentile, iGFR, % of life with CKD, low birth weight, treatment with antihypertensive medication, and hemoglobin). The significance level for all data analyses was set at P < 0.05. SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

There were 518 subjects who completed the pertinent study visit. Of those, 91 were excluded for age <6 years, and 44 were excluded for missing data. Therefore, BP measurements and neurocognitive testing results were available for 383 participants. EBP was common, occurring in 132 (34%) of the 383 participants. Seventy-four (56%) of these were prehypertensive, and 58 (44%) were hypertensive. On average, EBP subjects had a higher BMI percentile and had been diagnosed with CKD more recently than normal BP subjects. By definition, the EBP subjects had a higher median SBP and DBP index compared with normal BP subjects. No BP group differences were found with regard to age, gender, race/ethnicity, maternal education, iGFR, hemoglobin, and proportion with LBW. The majority of subjects in both groups were on antihypertensive medication (Table 1). Compared with normal BP subjects, subjects with EBP were less likely to be on an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (58% versus 46%, P = 0.05) but more likely to be on a calcium-channel blocker (9% versus 20%, P = 0.002). There was no difference between groups in the use of angiotensin receptor blockers (10% versus 11%, P = 0.86) or beta blockers (3% versus 7%, P = 0.10). Three or fewer subjects in each group were prescribed alpha blockers, α-beta blockers, or centrally acting α-2 agonists.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of subjects with normotension compared with those with EBP

| Characteristic | Normal BP (n = 251) | EBP (n = 132) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 13 (10 to 15) | 13 (10 to 15) | 0.94 |

| Male gender | 152 (61%) | 78 (59%) | 0.83 |

| African American race | 46 (18%) | 30 (23%) | 0.35 |

| Hispanic | 35 (14%) | 20 (16%) | 0.76 |

| BMI percentilea | 61 (31 to 85) | 70 (41 to 91) | 0.03 |

| Maternal education (college or more) | 76 (31%) | 39 (30%) | 0.81 |

| iGFRa | 44 (34 to 56) | 41 (30 to 54) | 0.19 |

| Low birth weight | 45 (19%) | 22 (17%) | 0.78 |

| % of life with CKDb | 92 (43 to 100) | 70 (21 to 99) | 0.01 |

| CKD duration (years)a | 9 (5 to 12) | 7 (3 to 11) | 0.03 |

| Treated hypertension | 68% | 71% | 0.64 |

| Glomerular CKD diagnosis | 57 (23%) | 40 (31%) | 0.12 |

| Nephrotic proteinuria | 34 (14%) | 23 (18%) | 0.29 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl)a | 12 (12 to 14) | 12 (11 to 14) | 0.78 |

| SBP indexa | 0.84 (0.80 to 0.89) | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.00) | <0.01 |

| DBP indexa | 0.80 (0.73 to 0.87) | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.01) | <0.01 |

Normal BP = SBP and DBP < 90th percentile; Elevated BP = SBP and/or DBP ≥ 90th percentile. EBP, elevated BP; SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; iGFR, GFR determined by plasma iohexol disappearance; IQR, interquartile range.

Median (IQR).

Duration is shown as percentage of life with CKD (%, IQR).

Group Comparisons on the Neurocognitive Variables

Bivariate analysis of neurocognitive testing data revealed that children with EBP had lower scores (worse performance) on the WASI Performance IQ (PIQ) and WASI Full Scale IQ compared with normal BP children with CKD (Table 2). In addition, PIQ scores were inversely correlated with SBP index (r = −0.13, P = 0.01) and with DBP index (r = −0.19, P < 0.001). By contrast, there was no significant difference between groups in the WASI Verbal IQ, WAIT-II, CPT-II, or the Parent BRIEF (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of neurocognitive test results for normal BP and EBP subjects (mean ± SD)

| Neurocognitive Test | Normal BP | EBP | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| WASI Verbal IQ | 98.4 ± 16.2 | 95.5 ± 18.1 | 0.11 |

| vocabulary | 47.5 ± 11.8 | 46.0 ± 12.3 | 0.25 |

| similarities | 49.3 ± 11 | 47.2 ± 12.8 | 0.11 |

| WASI Performance IQ | 96.1 ± 16.7 | 92.4 ± 14.9 | 0.03 |

| block design | 46.6 ± 11.5 | 44.3 ± 10.6 | 0.05 |

| matrix reasoning | 48.3 ± 11.2 | 45.5 ± 11 | 0.02 |

| WASI Full-Scale IQ | 97.0 ± 16.2 | 93.4 ± 16.5 | 0.04 |

| WIAT-II | |||

| basic reading | 96.0 ± 17 | 95.0 ± 18.7 | 0.62 |

| numeric operations | 94.3 ± 19.5 | 91.6 ± 22 | 0.26 |

| spelling | 96.3 ± 16.3 | 93.8 ± 17.9 | 0.21 |

| total achievement | 95.2 ± 17.3 | 93.3 ± 18.9 | 0.35 |

| CPT-II | |||

| omissions | 51.8 ± 12 | 52.7 ± 16.2 | 0.63 |

| commissions | 51.5 ± 10.6 | 52.0 ± 10.9 | 0.71 |

| BRIEF | |||

| BRI | 53.2 ± 10.9 | 54.0 ± 12.1 | 0.50 |

| MI | 55.5 ± 11.5 | 56.2 ± 10.9 | 0.53 |

| GEC | 54.7 ± 11.6 | 55.6 ± 11.1 | 0.43 |

EBP, elevated BP; WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence; WIAT-II-A, Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-II-Abbreviated; CPT-II, Conners' Continuous Performance Test-II; BRIEF, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions; BRI, behavior regulation index; MI, metacognition index; GEC, global executive composite.

The Relationship between Blood Pressure and Performance IQ

Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to further evaluate the association between increased BP and lower PIQ score (dependent variable). In all of these models, the analysis of residuals indicated that the assumptions required by the model were satisfied, and no data transformations were necessary. The independent variable of BP was defined categorically and continuously in three separate regression models, with EBP, SBP index, and DBP index each serving as the primary predictor of interest in each model. All other covariate definitions were kept constant across the three models. Increased BP was independently associated with lower PIQ score (worse performance) whether defined categorically (EBP; Table 3) or continuously (SBP index, DBP index; Table 4). BP index remained significantly associated with PIQ score, even when the regression analysis was restricted to subjects with BP in the normal range (SBP index: β = −1.86, P = 0.035; DBP index: β = −2.39, P < 0.001). In the first regression model, EBP and African American race were associated with lower PIQ scores (effect size relative to 1 SD PIQ score; EBP = 0.25, African American race = 0.57), whereas male gender and maternal education ≥16 years were associated with higher PIQ scores (effect size; male gender = 0.27, maternal education ≥16 years = 0.62), after controlling for the other covariates.

Table 3.

Multivariate regression analysis of associations with PIQ score (BP defined categorically)

| Characteristic | Regression Coefficient | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| EBP (yes/no) | −3.7 | −7.3 to −0.06 |

| Male (yes/no) | 4.0 | 0.41 to 7.6 |

| African American (yes/no) | −8.8 | −13.0 to −4.3 |

| Hispanic (yes/no) | −0.22 | −5.7 to 4.7 |

| Maternal education | ||

| <13 years | — | — |

| 13 to 15 years | 3.1 | −1.1 to 7.4 |

| ≥16 years | 9.2 | 5.1 to 13 |

| Age, years | −0.5 | −1.1 to 0.07 |

| BMI percentile | −0.01 | −0.07 to 0.05 |

| iGFRa | 1.0 | −0.02 to 2.0 |

| % life with CKDa | −0.29 | −0.84 to 0.26 |

| Low birth weight (yes/no) | −4.5 | −9.0 to 0.09 |

| Antihypertensive medication (yes/no) | −0.13 | −4.0 to 3.7 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | −0.3 | −1.1 to 0.49 |

PIQ, performance IQ; EBP, elevated BP; BMI, body mass index; iGFR, GFR determined by plasma iohexol disappearance; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CI, confidence interval.

per 10 units.

Table 4.

Multivariate regression analysis of associations with PIQ score (BP defined continuously)

| Characteristic | Model with SBP index |

Model with DBP index |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient | 95% CI | Regression Coefficient | 95% CI | |

| BP indexa | −1.16 | −2.1 to −0.21 | −1.17 | −1.8 to −0.55 |

| Male (yes/no) | 3.8 | 0.17 to 7.3 | 4.0 | 0.49 to 7.6 |

| African American (yes/no) | −8.5 | −13.0 to −4.0 | −7.8 | −12.3 to −3.4 |

| Hispanic (yes/no) | −0.06 | −5.0 to 4.8 | 0.07 | −4.8 to 4.9 |

| Maternal education | ||||

| <13 years | — | — | — | — |

| 13 to 15 years | 2.9 | −1.3 to 7.2 | 3.2 | −0.99 to 7.4 |

| ≥16 years | 9.0 | 4.9 to 13.1 | 9.1 | 5.1 to 13.2 |

| Age, years | −0.61 | −1.2 to −0.03 | −0.59 | −1.2 to −0.02 |

| BMI percentile | −0.004 | −0.07 to 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.08 to 0.04 |

| iGFRb | 1.0 | −0.03 to 2.0 | 0.76 | −0.26 to 1.8 |

| % of life with CKD | −0.24 | −0.78 to 0.30 | −0.3 | −0.83 to 0.23 |

| Low birth weight | −4.5 | −9.0 to 0.06 | −4.8 | −9.3 to −0.3 |

| Antihypertensive medication (yes/no) | −0.21 | −4.1 to 3.6 | −0.5 | −4.3 to 3.3 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | −0.32 | −1.1 to 0.47 | −0.06 | −0.85 to 0.73 |

PIQ, performance IQ; SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; BMI, body mass index; iGFR, GFR determined by plasma iohexol disappearance; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CI, confidence interval.

per 0.05 units.

per 10 units.

Treatment with antihypertensive medication was not associated with PIQ score (Tables 3 and 4). The results were similarly nonsignificant when the regression models were rerun using “Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (yes/no)” or “Calcium-channel blocker (yes/no)” rather than the covariate for all antihypertensive medications together (data not shown), an analysis that was done because of the imbalance in use of these antihypertensive medications between groups. In post hoc analysis, the effect of adding the underlying CKD diagnosis (glomerular versus nonglomerular) and nephrotic proteinuria (urine protein/creatinine >2) as covariates to the regression models was negligible (EBP, regression coefficient [β] = −3.5 [95% confidence interval {CI}: −7.2 to 0.1]; SBP index, β = −1.1 [95% CI: −2.1 to −0.2]; DBP index, β = −1.2 [−1.9 to −0.6]).

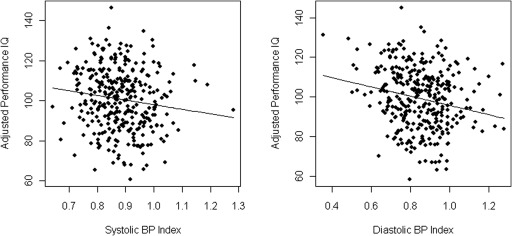

Among the EBP subjects, there was no difference between the strength of association of BP in the prehypertension range and that of BP in the hypertension range with PIQ score (data not shown). Figure 1 shows the relation between BP and adjusted PIQ scores for both SBP and DBP index.

Figure 1.

Partial residual plot of adjusted performance IQ versus BP index. (Left panel) Systolic BP. (Right panel) Diastolic BP.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine whether children with CKD and increased BP had poorer performance on selected tests of neurocognitive function when compared with normal BP children with CKD and to examine the relative contribution of BP to neurocognitive outcomes, taking into account sociodemographic and disease-related variables. The results showed that increased BP in children with mild-to-moderate CKD was independently associated with lower scores (worse performance) on WASI Performance IQ. In contrast, increased BP was not associated with measures of attention, verbal IQ, academic achievement, or parental ratings of executive functions. With regard to the other variables analyzed, socioeconomic status (race, maternal education) was most strongly associated with PIQ scores, whereas LBW and gender were also independently associated with PIQ score, but to a lesser extent. The strong association between maternal education level and improved performance on the WASI was expected and has been reported previously in the CKiD cohort (5). Other disease-related variables thought to affect cognition, such as disease severity and disease duration (1), were adjusted for in the multivariate analyses.

Performance IQ is a measure of nonverbal abilities and is generally linked to perceptual organization. More specifically, Performance IQ on the WASI is defined by the individual's scores on two subtests: Block Design and Matrix Reasoning (11). Block Design requires the individual to utilize visual-spatial organization, planning, and constructional abilities, whereas Matrix Reasoning requires the individual to utilize visual-spatial organization and nonverbal reasoning. Taken together, our results suggest that children with CKD may have difficulties with visual-spatial organization and visuoconstructive abilities that are related, in part, to increased BP, and perhaps implicate the dorsal pathway of the right hemisphere (i.e., the “where” pathway) (13). Deficits or dysfunction of these neurocognitive abilities may contribute to day-to-day problems involving spatially based math and science skills, directionality, reading maps, graphs, and charts. However, the difference in PIQ score between CKD subjects with EBP and those with normal BP was small, similar in magnitude to IQ decreases in lead toxicity associated with a 10 μg/dl rise in lead levels above the normal limit (14).

Despite significant variability (as reflected by the wide scatter in Figure 1), there was an inverse relationship between BP index and adjusted PIQ score in this study, suggesting that higher systolic and diastolic BP are associated with a lower PIQ score, even in the normotensive range. These results are consistent with a recent study in adults showing that the relation between global cognitive performance and SBP was linear, even in the normotensive range, with the best cognitive performance in subjects with SBP <120 mmHg (15).

It is important to note that the majority of subjects in this study reported being prescribed antihypertensive medication. There is little evidence that antihypertensive medications have significant direct adverse effects on cognitive function (16). However, studies have reported areas of small performance deficits as well as areas of slight improvement (17). In this study, analyses showed that treatment with antihypertensives was not associated with either higher or lower PIQ scores, implying that increased BP itself rather than its treatment was the factor associated with lower PIQ scores. Furthermore, the number of subjects on clonidine, a medication that can be used for both hypertension and inattention, was too small to affect the neurocognitive testing results.

Recent studies suggest that children with high BP have deficits in neurocognitive function, similar to young adults with hypertension (8,9,18,19). Children with CKD are at risk for neurocognitive dysfunction, and they are frequently hypertensive. Given the emerging evidence of neurocognitive deficits in children with primary hypertension, it is plausible that a similar hypertension-cognition link is present in children with hypertension secondary to CKD, and these findings would provide some support for this supposition. The existing literature on cognition and hypertension in children is mostly limited to subjects with untreated primary hypertension and shows executive function deficits in hypertensives, a result not found in this study. The difference in results may be due to the effects of kidney disease on the relation between BP and cognition or to the use of antihypertensive medication in the CKD subjects, which has been reported to improve executive function in children with primary hypertension (19).

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional study design limits inference about the causal relationship between increased BP and lower PIQ scores. First, although the relationship between increased BP and lower PIQ is intriguing, it is important to mention that we extracted the PIQ variable from a brief IQ measure (i.e., the WASI). Other measures of nonverbal abilities will need to be examined in relationship to elevated BP to support the findings obtained from this study. This would include the use of full IQ tests where additional measures of both verbal and nonverbal IQ are included, thus providing further examination of this relationship. Second, it is not clear whether the lower PIQ scores in subjects with increased BP were due to the BP itself or some other undetermined disease related factor that is associated with alteration of BP. The subjects did not have 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) at the time of neurocognitive assessment. Instead, BP status was determined using casual BP measurements that are known to correlate less well with hypertensive target organ damage compared with ABPM (20). Although ABPM is included in the CKiD study design, it is not done until at least 6 months after the initial neurocognitive assessment, the assessment that was analyzed in this report. In addition, categorization as EBP was determined using BP measurements from a single visit rather than BP readings over several occasions. Therefore, it is possible that there were some normal BP subjects in the EBP group and EBP subjects in the normal BP group. However, this limitation would have biased the study toward finding no difference between groups. The multivariate analyses did not include lead as a covariate, a known determinant of cognition in children. However, unpublished data show that the CKiD cohort has had only negligible lead exposure (J. Fadrowski, personal communication). Lastly, because the effects of BP on neurocognitive test performance are known to be subtle (8), we did not adjust the analyses for multiple comparisons. Although this approach permits the detection of more subtle differences, it could increase the risk of a type 1 error.

In summary, we report the novel finding of an association between higher BP and poorer neurocognitive function in children with CKD. This finding is particularly notable given the mild-to-moderate degree of CKD in the participants. Further studies are warranted to determine whether lowering of BP improves cognition in children with CKD. Longitudinal analysis of children in the CKiD cohort is planned to increase understanding of the relationships observed in this cross-sectional study.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Data in this article were collected by the CKiD with clinical coordinating centers (principal investigators) at Children's Mercy Hospital and the University of Missouri, Kansas City (Dr. Bradley Warady) and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (Dr. Susan Furth) and data coordinating center (principal investigator) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Dr. Alvaro Muñoz). The CKiD is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases with additional funding from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke; the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grants UO1-DK-66143, UO1-DK-66174, and UO1-DK-66116). The CKiD web site is located at www.statepi.jhsph.edu/ckid. We also especially thank the youth who have kidney problems and are participating in this study. This work was presented at the American Society of Nephrology 2009 Annual Meeting.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. Gipson DS, Duquette PJ, Icard PF, Hooper SR: The central nervous system in childhood chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 22: 1703–1710, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gipson DS, Hooper SR, Duquette PJ, Wetherington CE, Stellwagen KK, Jenkins TL, Ferris ME: Memory and executive functions in pediatric chronic kidney disease. Child Neuropsychol 12: 391–405, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gerson AC, Butler R, Moxey-Mims M, Wentz A, Shinnar S, Lande MB, Mendley SR, Warady BA, Furth SL, Hooper SR: Neurocognitive outcomes in children with chronic kidney disease: Current findings and contemporary endeavors. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 12: 208–215, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Furth SL, Cole SR, Moxey-Mims M, Kaskel F, Mak R, Schwartz G, Wong C, Muñoz A, Warady BA: Design and methods of the chronic kidney disease in children (CKiD) prospective cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1006–1015, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hooper S, Gerson AC, Butler R, Gipson DS, Lande M, Shinnar S, Wentz A, Chu MS, Furth SL, Warady B: Baseline cognitive functioning of children with mild to moderate chronic kidney disease: Preliminary findings from the CKiD project [Abstract]. E-PAS2007:617920 5 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flynn JT, Mitsnefes M, Pierce C, Cole SR, Parekh RS, Furth SL, Warady BA, Chronic Kidney Disease in Children Study Group: Blood pressure in children with chronic kidney disease: A report from the chronic kidney disease in children study. Hypertension 52: 631–637, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitsnefes M, Ho PL, McEnery PT: Hypertension and progression of chronic renal insufficiency in children: A report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS). J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2618–2622, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Waldstein SR, Snow J, Muldoon MF, Katzel LI: Neuropsychological consequences of cardiovascular disease. In: Medical Neuropsychology, 2nd Ed., edited by Tarter RE, Butters M, Beers SR. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2001, pp 51–83 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lande MB, Kaczorowski JM, Auinger P, Schwartz GJ, Weitzman M: Elevated blood pressure and decreased cognitive function among school-age children and adolescents in the united states. J Pediatr 143: 720–724, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 114[Suppl 2]: 555–576, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O: A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary, 3rd Ed., New York, Oxford University Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwartz GJ., Furth S., Cole SR., Warady B., Muñoz A: Glomerular filtration rate via plasma iohexol disappearance: Pilot study for chronic kidney disease in children. Kidney Int 69: 2070–2077, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ettlinger G: “Object vision” and “spatial vision”: The neuropsychological evidence for the distinction. Cortex 26: 319–341, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canfield RL, Henderson CR, Jr, Cory-Slechta DA, Cox C, Jusko TA, Lanphear BP: Intellectual impairment in children with blood lead concentrations below 10 microg per deciliter. N Engl J Med 348: 1517–1526, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knecht S, Wersching H, Lohmann H, Bruchmann M, Duning T, Dziewas R, Berger K, Ringelstein EB: High-normal blood pressure is associated with poor cognitive performance. Hypertension 51: 663–668, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muldoon MF, Waldstein SR, Jennings JR: Neuropsychological consequences of antihypertensive medication use. Exp Aging Res 21: 353–368, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muldoon MF, Waldstein SR, Ryan CM, Jennings JR, Polefrone JM, Shapiro AP, Manuck SB: Effects of six anti-hypertensive medications on cognitive performance. J Hypertens 20: 1643–1652, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lande MB, Adams H, Falkner B, Waldstein SR, Schwartz GJ, Szilagyi PG, Wang H, Palumbo D: Parental assessments of internalizing and externalizing behavior and executive function in children with primary hypertension. J Pediatr 154: 207–212, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lande MB, Adams H, Falkner B, Waldstein SR, Schwartz GJ, Szilagyi PG, Wang H, Palumbo D: Parental assessment of executive function and internalizing and externalizing behavior in primary hypertension after anti-hypertensive therapy. J Pediatr 157: 114–119, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Urbina E, Alpert B, Flynn J, Hayman L, Harshfield GA, Jacobson M, Mahoney L, McCrindle B, Mietus-Snyder M, Steinberger J, Daniels S, American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in Youth Committee: Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: Recommendations for standard assessment: A scientific statement from the american heart association atherosclerosis, hypertension, and obesity in youth committee of the council on cardiovascular disease in the young and the council for high blood pressure research. Hypertension 52: 433–451, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]