Abstract

Context

Cerebral cortical volume enlargement has been reported in 2- to 4-year-olds with autism. Little is known about the volume of sub-regions during this period of development. The amygdala is hypothesized to be abnormal in volume and related to core clinical features in autism.

Objective

To examine amygdala volume at 2 years with follow-up at 4 years of age in children with autism and to explore the relationship between amygdala volume and selected behavioral features of autism.

Design

Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study.

Setting

University medical setting.

Participants

Fifty-two autistic and 33 control (11 developmentally delayed, 22 typically developing) children between 18 and 35 months (2 years) of age followed up at 42 to 59 months (4 years) of age.

Main Outcome Measures

Amygdala volumes in relation to joint attention ability measured with a new observational coding system, the Social Orienting Continuum and Response scale; group comparisons including total tissue volume, sex, IQ and age as covariates.

Results

Amygdala enlargement was observed in subjects with autism at both 2 and 4 years of age. Significant change over time in volume was observed, though the rate of change did not differ between groups. Amygdala volume was associated with joint attention ability at age 4 years in subjects with autism.

Conclusions

The amygdala is enlarged in autism relative to controls by age 2 years but shows no relative increase in magnitude between 2 and 4 years of age. A significant association between amygdala volume and joint attention suggests that alterations to this structure may be linked to a core deficit of autism.

Introduction

Autism is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder likely involving multiple brain systems. Converging evidence from magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, head circumference, and post-mortem studies suggests that brain volume enlargement is a characteristic feature of autism,1 with its onset most likely occurring in the latter part of the first year of life2. On the basis of functional MR imaging data identifying decreased amygdala activity during gaze processing3, Baron-Cohen et al.4 first proposed that amygdala dysfunction may account for core social characteristics of autism. Neuropathological and structural MR imaging studies have also highlighted alterations within the amygdala. Post-mortem studies of individuals with autism have noted immature appearing and densely packed cells5, 6 and fewer neurons within the amygdala.7 Abnormal amygdala volumes have been observed across multiple structural MRI studies of adolescents and adults with autism.8–13 Altered amygdala activation in response to facial and emotion processing tasks also has been reported in functional MR imaging studies of individuals with autism. 14–16 Abnormal activation patterns were not evident in functional neuroimaging studies of individuals with autism presented with non-facial social processing paradigms. 17–20 Taken together, studies of the amygdala in autism suggest that both the morphologic characteristics and function of this structure are abnormal and that amygdala dysfunction may be associated with social deficits involving facial processing.

Adolphs et al.21 observed deficits in recognition of negative facial emotions among patients with bilateral focal lesions of the amygdala. The authors reported that these deficits were the consequence of a failure to orient to the eye region when viewing faces. Sasson et al.22 recently reported that, on an emotion recognition task sensitive to deficits related to amygdaladamage,23 individuals with autism show decreased attention to face regions relative to age and IQ matched healthy controls and age-matched individuals with schizophrenia. Individuals with autism in this study, in contrast to healthy controls and individuals with schizophrenia, did not modulate their attention to social scenes according to whether faces were present or absent. Failure to orient to faces and, more specifically, the eye region of the face, is inherent in multiple aspects of social impairment unique to autism (e.g., joint attention (JA), facial emotion processing) and may be linked to amygdala abnormalities. Multiple studies have identified JA deficits as the most reliable marker of autism in the first two years of life24–31 and thus suggest that the amygdala plays a key role in neurodevelopmental alterations unique to autism.

Both increased12, 13 and decreased8–11 amygdala volumes have been noted in structural MR imaging studies of individuals with autism. Schumann et al.12 first suggested that inconsistencies across studies are the result of age-dependent effects. Observing amygdala enlargement in school-aged (7–12 years) but not adolescent (12–18 years) autistic children, the authors hypothesized that enlargement of the amygdala in autism is an early occurring phenomenon. Consistent with this report, Sparks et al.13 reported amygdale enlargement in 3–4 year olds with autism whereas studies of adolescents and adults with autism have highlighted reduced amygdale volumes compared with typically developing individuals.8, 10 None of these studies have observed individuals over time. Giedd et al.32 previously showed that longitudinal studies are necessary for characterizing neuroanatomical development within the context of inter-individual variability and non-linear growth. Studies of amygdala growth in young children with autism followed over time are needed to map developmental patterns and brain – behavior relationships unique to this disorder.

Two recent studies reported that amygdale volume is associated with social deficits in autism. Examining the sample from the Sparks et al.13 study, Munson et al.33 reported that right amygdale enlargement at age 3–4 years is associated with worse concomitant social functioning and is predictive of worse social functioning at age 6 years. However, that study did not specify the aspects of social impairment in autism associated with amygdale volume. Nacewicz et al.9 reported that amygdala volumes were reduced in a small group of adolescents with autism (N=21), and that decreased amygdala volume was significantly associated with decreased amount of time spent fixating on the eye region of faces.9

We examined amygdale volumes and growth in children with autism at 2 years of age (the earliest age of generally accepted diagnosis) with follow up at 4 years of age. We developed an observational coding system to examine joint attention and its relationship to amygdala volume. JA was targeted because (1) it consistently has been shown to be impaired in young children with autism, 24–31 and (2) as measured herein, it requires attention to the eye region of the face. Amygdala volumes were hypothesized to be enlarged in autism and significantly associated with JA deficits that involve orienting to the eye region but would not be associated with other social behaviors not involving orienting to the eye region (e.g., nonverbal gesture). Amygdala volumes also were examined in relation to non-social characteristic features of children with autism, specifically restricted and repetitive behaviors.

Methods

Sample

Fifty-two children with autism entered this MRI study at two years (18–35 months) of age, 31 of whom were followed up at approximately 4 years of age (42–59 months of age; Table 1). Thirty-three control subjects (22 typically-developing [TYP] children and 11 non-autistic, developmentally-delayed [DD)] children) entered the study at 2 years of age. The sample of control children was enriched with DD children to more closely match the autism study group in terms of IQ. The TYP and DD children were not analyzed separately because of the small sample sizes. Twenty control subjects (12 TYP, 6 DD) were followed up at 4 years of age. Further details of subject ascertainment are reported elsewhere.2 In an earlier analysis of this sample performed at age 2 years,34 we observed a mean developmental quotient of approximately 54 for children with autism. We hypothesized that our ascertainment of very young children with autism may have been biased towards identifying individuals with more severe presentations and/or lower IQ that led to their detection at age 2 years. We therefore began to enrich this sample with high-functioning autistic (HFA) subjects at age 4 years. At the time of the present analysis, 2 HFA subjects were added to the sample, for a total of 54 autistic subjects entering this study.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Time | Variable | Autism (N=50) | Controls (N=33) | DD (N=11) | Typical (N=22) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| 1 | Age, y | 2.68 | 0.32 | 2.58 | 0.55 | 2.83 | 0.42 | 2.46 | 0.53 |

| Mullen comp IQa | 53.78 | 9.02 | 89.21 | 27.40 | 56.58 | 16.94 | 105.82 | 15.98 | |

| Mullen AE/Age | 0.55 | 0.17 | 0.95 | 0.31 | 0.53 | 0.27 | 1.11 | 0.22 | |

| Sex, No. (%) Male | 86% | 73% | 90% | 73% | |||||

| 2 | (N=31) | (N=20) | (N=6) | (N=14) | |||||

| Age, y | 5.01 | 0.42 | 4.70 | 0.47 | 4.97 | 0.49 | 4.59 | 0.53 | |

| Mullen comp IQa | 56.58 | 16.94 | 95.32 | 28.40 | 56.00 | 6.77 | 112.31 | 12.34 | |

| Mullen AE/Age | 0.53 | 0.27 | 0.94 | 0.34 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 1.10 | 0.20 | |

| Sex, No. (%) Male | 90% | 70% | 50% | 79% | |||||

Abbreviations. AE = age equivalents; DD = developmentally delayed; Age = age in years;

Mullen comp IQ = Mullen Scales of Early Learning composite IQ standard score

Subjects with autism were referred after receiving a clinical diagnosis or while on a waiting list for a clinical evaluation of autistic disorder. Subjects with DD were included only if they had no identifiable cause for their delay (e.g., prematurity, genetic or neurological disorder) and no evidence of a Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD) after being screened with the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). The DD and TYP children were excluded if they had CARS scores of 30 or greater. Medical records were also reviewed and DD subjects were excluded for evidence of autism, PDD-NOS or the previously mentioned medical conditions. A standardized neurodevelopmental examination was administered to exclude subjects with any notable dysmorphologic characteristics, evidence of neurocutaneous abnormalities, or other significant neurological abnormalities. All subjects were excluded if they had evidence of a medical condition thought to be associated with autism,35 including Fragile X Syndrome or tuberous sclerosis. Cytogenetic or molecular testing was used to rule out Fragile X Syndrome in autistic and DD subjects. Subjects were also excluded if they had evidence of gross central nervous system injury (e.g., cerebral palsy, significant complications or perinatal/postnatal trauma, drug exposure), seizures, or significant motor or sensory impairment. Study approval was obtained from both the University of North Carolina (UNC) and Duke Institutional Review Boards and written informed consent (from parents) was secured.

Clinical Assessment

Children between 18 and 35 months of age (time 1) were eligible for inclusion in this study. Medical records were reviewed. Diagnosis was confirmed by the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R).36 Subjects were included in the autism group if they met e interview’s algorithm criteria, had Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)37 consistent with autism and met DSM-IV criteria for autistic disorder. The diagnosis was reassessed at age 42 to 59 months (time 2), and 3 subjects who no longer met criteria for autistic disorder based on the foregoing diagnostic criteria were not included in the final analyses.

All subjects were assessed on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning38 and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS).39 The Repetitive Behavior Scale – Revised (RBS-R)40 also was administered to assess six domains of repetitive behaviors: stereotypical behaviors (i.e., purposeless movements that are repeated in a similar manner), self-injurious behaviors (i.e., behaviors that cause physical self-harm and are repeated), compulsive behaviors (i.e., behaviors that are repeated according to a rule), ritualistic behaviors (i.e., activities of daily living repeated in a similar manner), sameness behavior (i.e., resistance to change), and restricted behavior (i.e., limited range of focus, interest or activity). The RBS-R was examined in relation to amygdala volume in order to assess the specificity of hypothesized relationships between the amygdala and JA.

We developed a measure of social orienting, the Social Orienting Continuum and Response Scale (SOC-RS),41 that has been previously validated and that incorporates both dimensional and categorical response codes. The SOC-RS ratings are applied during observation of videotaped ADOS sessions. Ratings are performed for social orienting and communication behaviors including initiating JA (IJA), responding to JA (RJA), and nonverbal gestures.

After initial analyses of behavioral data, key items were selected for analysis with the present MRI data. Joint attention was examined in this study on the basis of its dependence on attention to the eye region of the face. Joint attention was defined as an event in which children either initiate directing another person’s attention towards an object through the use of eye-gaze (i.e., IJA) or follow someone else’s attention towards an object by following a shift in eye-gaze (i.e., RJA). JA variables, therefore, assess children’s abilities when communicating attention by focusing on another individual’s eyes or responding to cues specifically offered by eye movements from others. In contrast to other behaviors scored within the SOC-RS, joint attention requires that children attend to the eye region and process shifts in eye-gaze. An IJA is scored if children start a JA and refer to the face of their social partner to monitor that person’s attention (i.e., if children point to an object but do not look at the examiner, then the event is not scored). An RJA is scored if children follow a shift in eye-gaze by the examiner during the scheduled JA press of the ADOS. Children were not included in analyses of RJA if this activity was not observed on camera. If children did not respond to one of 5 trials, then they were scored as non-responders. Although children were given the opportunity to merely follow a pointing gesture by the examiner during the ADOS, only events in which children followed a shift in eye-gaze were scored because of our interest in children’s ability to process information from the eyes. A JA total (JAT) score was computed by assigning a score of 1 for children who scored greater than 0 on either the IJA or RJA variables. The rate of nonverbal communicative gestures not involving attention to the eye region (pointing, clapping) was also examined as a control variable to investigate the specificity of relationships between amygdala volume and JA variables. Gesture rate scores were calculated by dividing the frequency by total observed time.

To eliminate bias from inadequate sampling, children were not included in analyses if they were not observable on camera for at least 10 minutes. This minimum time limit was set to allow for a representative sample of behavior. Because final analyses only compared rates (frequency/time) of behaviors and responses that were presented to each individual over a fixed number of trials, duration of observable behavior should not affect results.

To establish reliability of SOC-RS items, raters independently coded 15 videotaped ADOS sessions two times. Reliability was calculated by means of intraclass correlation coefficients. After establishing an intrarater and interrater reliability score of greater than 0.8 across these 15 cases, each rater independently coded cases for final analysis. Good interrater reliability was observed for IJA (0.80), RJA (0.86) and gestures (0.81).

MR Image Acquisition

All subjects underwent imaging on a 1.5 MR scanner imager (Signa; General Electric Co., Milwaukee, Wisconsin) at the Duke—University of North Carolina Brain Imaging and Analysis Center located at Duke University Medical Center. Image acquisition was designed to maximize gray/white tissue contrast at age 2 to 4 years and included the following: (1) a coronal T1 inversion recovery prepared: inversion time, 300 milliseconds, repetition time, 12 milliseconds, echo time, 5 milliseconds, 20° flip angle; 1.5-mm thickness with 1 excitation; 20-cm field of view; and 256 × 192 matrix and (2) a coronal protein density/T2 two-dimensional multislice dual echo fast spin echo: repetition time, 7200 milliseconds, echo time, 17/75 milliseconds; 3.0-mm thickness with 1 excitation, 20-cm field of view; and 256 × 160 matrix. A series of localizer images and a set of phantoms were used to standardize assessments over time and across individuals.

At both time points, in preparation for imaging, subjects with autism and subjects with DD received moderate sedation (combination of pentobarbital sodium and fentanyl citrate as per hospital sedation protocol) administered by a nurse and under the supervision of a pediatric anesthesiologist. A more detailed description appears elsewhere.42 At age 2 years, TYP subjects underwent imaging without sedation, in the evening, during natural sleep. At age 4 years, a subset of 5 TYP subjects were trained to lie still in a practice imager by means of behavioral techniques, including desensitization and positive reinforcement; children viewed videos of their choice and the video remained on while children remained still.43 Parents of TYP children identified whether they wished their children to participate with or without the behavioral training. All images were reviewed by a pediatric neuroradiologist for significant clinical abnormalities. No evidence of qualitative neuroanatomical abnormalities was observed for any of the children included in the present study, on the basis of a clinical review by a neuroradiologist.

Image Processing

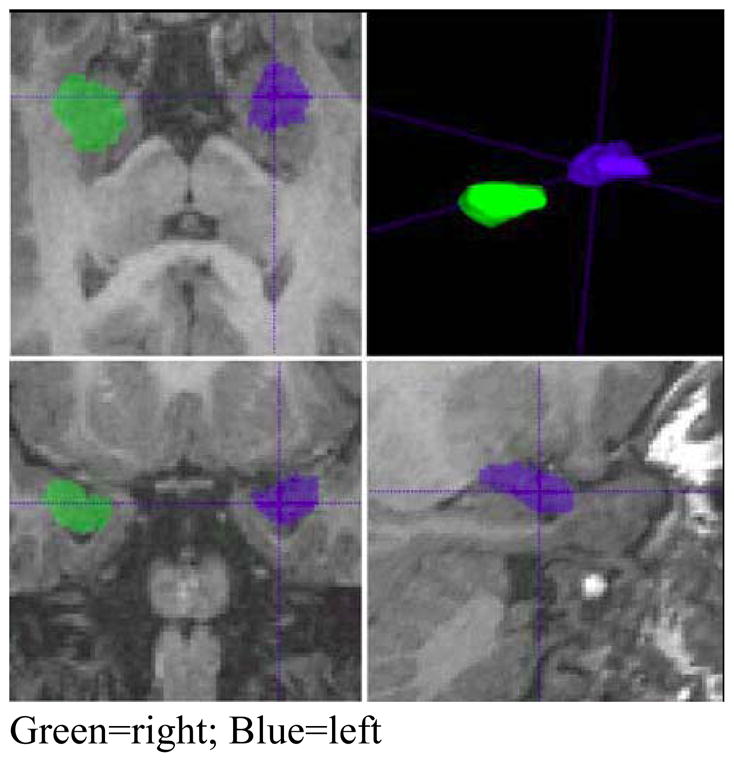

A standardized tracing protocol was used for the amygdala and briefly is described as follows. Reliability was obtained by two raters who made independent measurements on a set of 15 images, which included 5 images repeated 3 times (in random order). The was manually traced on high resolution T1 images aligned along the long axis of the hippocampus by means of the IRIS/SNAP tool44 following a protocol developed by the Center for Neuroscience and the M.I.N.D. Institute at the University of California, Davis.10 We first established reliability with the M.I.N.D. Institute group (average interrater reliability, 0.90) on adult subjects. Subsequently, reliability was established on images from our sample of 18- to 35-month-olds. Average intrarater reliability was r = 0.93, and inter-rater reliability was r = 0.90. A single rater (r = 0.90) performed all amygdala traces. See Figure 1 for an example of amygdala tracing.

Figure 1.

Example of amygdala segmentations

Sample segmentation of right and left amygdala using IRIS software. Image is presented in radiological orientation with the right hemisphere visualized on the left side of the image (green) and the left hemisphere on the right side (blue).

Statistical Analyses

Group differences were evaluated for age, sex, and developmental IQ. As expected, given the disproportionate rate of males with autism, sex was unequally distributed across groups. Sex also is known to be associated with brain volume and, therefore, was included as a covariate in all analyses. An insufficient number of females with autism were available to perform separate analyses by sex. Given the variability of age across subjects (18–35 months), age was also included as a covariate. The IQ of the autistic group was significantly lower than that of the controls; therefore IQ was included in the analyses as a covariate.

The first set of analyses examined group differences in amygdala volumes and growth rates. A series of mixed models with repeated measures of the amygdala volume domains (hemisphere, time) were fit with amygdala volume as the dependent variable, diagnostic group as the predictor of interest, and age, sex, and IQ as covariates. This resulted in up to 4 observations per subject (left and right amygdala, times 1 and 2). Diagnostic group was entered as a 2 level categorical variable (autism, controls). Estimates for the controls were created by using post-estimation procedures to combine the group estimates. Age, sex, IQ and group were included as predictors in each of the models along with all 2-, and 3-way interactions with hemisphere (right or left) and group. The significance of the interactions with hemisphere was examined. If none of these interactions was significant, then the effects were reported as averages across the left and right amygdala. To evaluate whether the group difference was proportional to that observed in total tissue volume (TTV), a second model was fit that added TTV and the 2-way interaction with age. The TTV included all cortical, subcortical, and brainstem gray and white matter and was selected rather than total brain volume because it provides a more specific index of brain enlargement without inclusion of increases due to ventricular enlargement. Results using total brain volume were not different than those using TTV for the analyses.

Relationships between JA and amygdala volume were examined by adding the SOC-RS JA ratings and interaction terms to the models described previously. The IJA, RJA, JAT, and gestures were examined separately. Two-tailed tests were conducted for the amygdala-behavioral analyses.

Results

Amygdala Volume

Because of insufficient image quality or artifact, we were unable to adequately visualize the amygdala in eight subjects (5 with autism, 1 TYP, and 2 DD). The ratio of images that were of insufficient quality did not differ between diagnostic groups.

Significant hemisphere effects were observed across groups for amygdala volumes, F (2, 85) =3.14, p=.048. Right amygdala volumes were larger than left amygdala volumes. Therefore, analyses are reported separately for the right and left amygdala.

Change Over Time

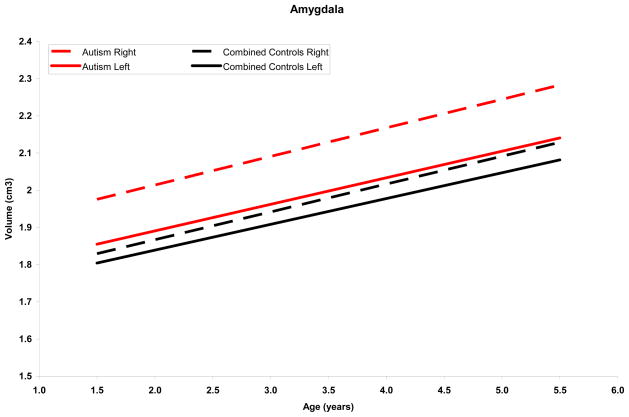

Amygdala volume increased significantly over time in the total sample of autistic and control subjects (β = 0.14, SE = 0.02, p < .001) (Figure 2). The slope of amygdala growth remained positive and significant after adjusting for TTV (β = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p =.002). Group comparisons of change in amygdala volume over time were not significant before or after controlling for TTV.

Figure 2.

Amygdala growth adjusted for age, IQ and total tissue volume

Mean right and left amygdala growth trajectories for the autism and control groups adjusted for age, IQ, and total tissue volume. Both groups show significant growth, but the rate of change does not differ between groups.

Because no group differences were observed in rate of amygdala volume change over time, amygdala volumes at times 1 and 2 were averaged (Tables 2–3). When average amygdala volumes were compared, individuals with autism had significantly larger right and left amygdala volumes than controls. After controlling for TTV, only the right amygdala remained enlarged in the autism group relative to the control group. Results did not change when the two high-functioning children with autism were excluded from analyses; nor did they change when females were excluded.

Table 2.

Group Means and Differences in Amygdala Volume Adjusted for Age, Sex and IQ

| Time 1 | Difference, Mean (SE), mm3 | P Value | Percentage Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0.324 (0.085) | .03 | 20 |

| Right | 0.368 (0.086) | <.001 | 23 |

| Left | 0.279 (0.088) | <.001 | 18 |

| Time 2 | |||

| Total | 0.249 (0.102) | .02 | 13 |

| Right | 0.293 (0.105) | .006 | 15 |

| Left | 0.204 (0.104) | .05 | 11 |

| Main Effect | |||

| Total | 0.295 (.085) | <.001 | 17 |

| Right | 0.339 (.087) | <.002 | 19 |

| Left | 0.250 (.087) | .005 | 15 |

Table 3.

Group means and Differences in Amygdala Volume Adjusted for Age, Gender, IQ, and Total Tissue Volume (TTV)

| Time 1 | Difference, Mean (SE), mm3 | PValue | Percentage Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0.090 (0.073) | .22 | 5 |

| Right | 0.135 (0.076) | .08 | 7 |

| Left | 0.046 (0.076) | .55 | 2 |

| Time 2 | |||

| Total | 0.104 (0.084) | .22 | 5 |

| Right | 0.149 (0.088) | .10 | 7 |

| Left | 0.060 (0.085) | .48 | 3 |

| Main Effect | |||

| Total | 0.096 (0.065) | .15 | 5 |

| Right | 0.140 (0.069) | .045 | 7 |

| Left | 0.051 (0.067) | .45 | 3 |

Amygdala and JA

Clinical correlates of amygdala volume were examined for the autism group only; ADOS (and consequently, SOC-RS) data were not available for controls. At time 1, 8 of 39 children with autism (21%) initiated and/or responded to JA (i.e., a JAT score of 1); 9 of 23 children (39%) initiated and/or responded to JA at time 2. At time 1, 7 of the 39 autistic children (18%) initiated JA; 9 of 23 children (39%) initiated JA at time 2. At time 1, 7 of 39 children with autism (18%) responded to JA (i.e., shifts in eye gaze) bids from the examiner; at time 2, 4 of 21 children (19%) responded to JA initiated by the examiner. At time 1, 19 of 39 children (49%) made at least 1 nonverbal communicative gesture; 16 of 24 (67%) gestured at time 2.

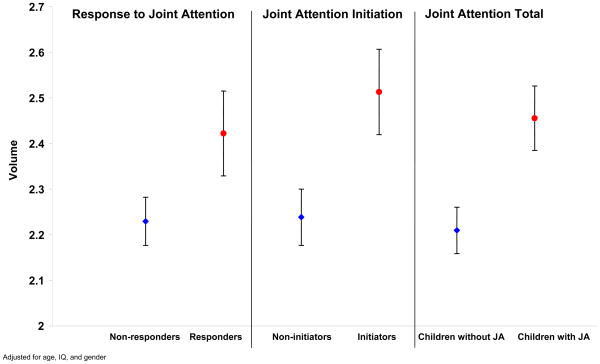

The relationship between amygdala volume and JA indices did not differ when right and left amygdala volume were analyzed separately; therefore, right and left volumes were averaged and combined for analysis. A significant positive association was observed at age 4 years between amygdala volume and JAT at age 4 years (Figure 3; β = 0.25, SE = 0.07, p<.001). This relationship was also significant for amygdala volume and IJA (Est. = 6.04, SE = 2.04, p=.006); and between amygdala volume and RJA (β = 0.19, SE = 0.09, p=.04). The relationship between amygdala volume and gestures was not significant for either 2 or 4 year-olds with autism. The relationships between amygdala volume and the six subscales of the RBS-R were not significant at age 2 or age 4 years. Results did not change after exclusion of females from the analyses.

Figure 3.

Time 2 amygdala volumes for children with autism who did and children with autism who did not engage in joint attention

Mean and standard error of amygdala volumes (average of right and left amygdala) contrasted for children with autism who did and did not engage in joint attention (JA) adjusted for age, IQ, and sex.

Discussion

Comparison of amygdala volume showed bilateral enlargement in children with autism. Right amygdala volume was enlarged disproportionate to TTV increases and left amygdala was enlarged proportionately to TTV increases. Consistent with previous research7,33 right amygdala enlargement was found to be more robust than left amygdala enlargement. Autistic subjects showed a 5% increase in TTV at ages 2 to 4 years34 while observed amygdala volumes were 16% larger than the group of 2 to 4 year-old controls. Amygdala enlargement was present by age 2 years. Growth trajectories between 2 and 4 years of age did not differ in autistic children and non-autistic controls. These findings suggest that, consistent with a previous report of head circumference growth rates in autism34 and studies of amygdala volume in childhood,12, 13, 33 amygdala growth trajectories are accelerated before age 2 years in autism and remain enlarged during early childhood. Moreover, amygdala enlargement in 2-year-old children with autism is disproportionate to overall brain enlargement and remains disproportionate at age 4 years.

Amygdala enlargement in autism was associated with increased JA and, despite the findings that only the right amygdala volume was increased relative to TTV enlargement, the strength of the relationship between JA and amygdala volumes did not differ by hemisphere. It is important to note that the left amygdala is enlarged but this enlargement is not disproportionate to TTV. These results are consistent with both prior studies establishing a significant association between amygdala volume and social functioning in autism.9,33

Amygdala enlargement was associated with JA ability at age 4 years but not with communicative gestures. Analysis of the relationship between caudate nuclei volumes and JA in this sample was not significant at either 2 or 4 years of age (unpublished data) suggesting that the relationship between amygdala volume and JA is specific. JA is distinct from other social behaviors measured in the present study because it involves social orienting and eye contact with others. Adolphs21 postulated that damage to the amygdala limits individuals’ natural tendency to orient to the eye region of faces. The observation that amygdala volume is associated with JA and not other social behaviors suggests that amygdala alterations in autism reflect diminished social orienting behavior and, more specifically, reduced tendency to coordinate eye contact. Reduced JA engagement in autism precludes shared social experiences and thus can have a cascade of developmental effects, including disrupted cognitive, communication, and social cognitive growth.26 The association between amygdala volume abnormalities and attention to eyes has now been established in two independent studies (the present study and that of Nacewicz et al9), suggesting that that this association is evident from early childhood through adulthood.

Nacewicz et al.9 reported decreased amygdala volumes associated with reduced eye contact in adolescents and adults with autism. The association between amygdala enlargement and increased JA ability in autism observed herein is consistent with these findings but also suggests non-linear growth patterns in autism.45 Both Schumann and Amaral7 and Nacewicz et al.9 hypothesize an ‘allostatic overload’ model to explain non-linear patterns of amygdala growth in autism. Within this model, repeated exposure to a highly stimulating event leads to a compensatory response (allostasis) within the amygdala including increased dendritic arborization and consequent overgrowth. The compensatory response involves excess production of corticotropins and glucocorticoids that, upon surpassing a threshold concentration (allostatic overload), result in cell death within the amygdala. Initial amygdala hypertrophy in autism is thus followed by reduced amygdala volume later in development. The present results indicate that amygdala enlargement emerges before age 2 years and persists, but does not increase in magnitude, between 2 and 4 years of age. This enlargement is associated with attention to eyes and, although the mechanisms linking amygdala enlargement and JA ability are not known, the present results are consistent with the hypothesis that an allostatic process in which dendritic arborization and overgrowth result from sensitivity to processing eyes is evident in autism at approximately age 4 years.

The amygdala plays a critical role in early stage processing of facial expression19, 46–48 and in alerting cortical areas to the emotional significance of an event.49 The amygdala, via afferent connections projecting from the superior colliculus and pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus,50 alerts upstream cortical regions, including the fusiform face area of the fusiform gyrus, orbitofrontal cortex, and superior temporal sulcus, to the emotional salience of stimuli such as faces. Damage to the primate amygdala during adulthood has inconsistent effects on social interactions but, if occurring during infant development, leads to increased social fear within novel environments51, 52. Amygdala disturbances early in development, therefore, disrupt the appropriate assignment of emotional significance to faces and social interaction.

Schultz53 previously suggested that early amygdala alterations in autism during social processing contribute to later deficits in face processing and higher order social cognition. He hypothesized that experience with faces in infancy corresponds with enhanced salience assigned by the amygdala which, in turn, leads to motivation to preferentially allocate attentional resources to faces. Dawson et al.26 hypothesized that early social deprivation in autism resulting from a lack of social attention (and concomitant failure to promote interaction through JA) disrupts normative trajectories of neural and behavioral development. The association between amygdala enlargement and JA ability observed herein thus suggests that amygdala overgrowth in autism may contribute to subsequent cortical face processing system disturbances54 and core social and cognitive developments as are evident in autism. The primary limitation within this study was that few children with autism demonstrated JA abilities at age 2 or 4 years. The behavioral observations coded for the present study target multiple social behaviors and provide only a small number of presses for JA. Inclusion of additional attempts to elicit JA across multiple contexts may increase power to identify children with autism who engage in JA at earlier ages. An additional limitation was that the relationship between amygdala volume and JA could not be investigated in control groups. Assessing whether the pattern of amygdala-JA findings differs in autistic and non-autistic children will be important for understanding brain-behavior associations unique to autism. Last, the small number of females with autism included in our study suggests that future investigation is needed to determine whether amygdala enlargement and the observed relationship between amygdala volume and JA each are evident in females with autism.

Conclusions

We observed bilateral amygdala enlargement in a large sample of 2-year-olds with autism that persisted through 4 years of age. This enlargement was disproportionate to TTV enlargement for the right amygdala as well. Continued follow up (now under way) of this sample will be necessary to examine whether amygdala growth rates in autism continue to parallel those seen in non-autistic individuals, or whether a second period of accelerated growth or period of volumetric atrophy occurs in autism after age 4 years. Similarly, longitudinal MR imaging studies of high risk neonates will provide insights into the onset of amygdala overgrowth in autism.

Acknowledgments

We express our appreciation for the assistance we received from the following:

NDRC Autism Subject Registry, and the NC Children’s Developmental Services Agencies for assisting with recruitment; Chad Chappell, M.S., Nancy Garrett, B.A., Michael Graves, B.A., Sarah Peterson, M.A., and Matthieu Jomier, M.S. for their work on the imaging and behavioral data collection; Cynthia Schumann, David Amaral, and Julia Hamstra for assisting with amygdala tracing; and participating families.

Research supported by NIH grants MH61696 (J Piven), HD03110 (J Piven), and EB002779 (G Gerig)

Footnotes

Portions of this paper were presented at the 2007 International Meeting for Autism Research (IMFAR): Seattle, WA

Financial disclosures

Dr. Mosconi, Dr. Cody-Hazlett, Dr. Poe, Dr. Gerig, Ms. Gimpel-Smith, and Dr. Piven each report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts relevant to this manuscript.

Dr. Matthew Mosconi has had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Matthew W. Mosconi, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois-Chicago.

Heather Cody Hazlett, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill.

Michele D. Poe, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill.

Guido Gerig, Departments of Psychiatry and Computer Science, University of Utah and University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Rachel Gimpel Smith, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill.

Joseph Piven, UNC Neurodevelopmental Disorders Research Ctr, University of North Carolina, CB#3367, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3367

References

- 1.Mosconi M, Zwaigenbaum L, Piven J. Structural MRI in autism: Findings and future directions. Clin Neurosc Res. 2006;6:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hazlett HC, Poe MD, Gerig G, Smith RG, Provenzale J, Ross A, Gilmore J, Piven J. Magnetic resonance imaging and head circumference study of brain size in autism: Birth through age 2 years. Arch Gen Psych. 2005;62:1366–1376. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron-Cohen S, Ring HA, Wheelwright S, et al. Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: an fMRI study. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1891–1898. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron-Cohen S, Ring HA, Bullmore ET, Wheelwright S, Ashwin C, Williams SC. The amygdala theory of autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:355–364. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey A, Luthert P, Dean A, Harding B, Janota I, Montgomery M, Rutter M, Lantos P. Autism and megalencephaly. Brain. 1998;121:889–905. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauman M, Kemper T. Histoanatomic observations of the brain in early infantile autism. Neurology. 1985;35:866–874. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.6.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schumann CM, Amaral DG. Stereological analysis of amygdala neuron number in autism. J Neurosci. 2006 July 19;26(29):7674–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1285-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aylward EH, Minshew NJ, Goldstein G, et al. MRI volumes of amygdala and hippocampus in non-mentally retarded autistic adolescents and adults. Neurology. 1999 December 10;53(9):2145–50. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nacewicz BM, Dalton KM, Johnstone T, et al. Amygdala volume and nonverbal social impairment in adolescent and adult males with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 December;63(12):1417–28. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce K, Muller RA, Ambrose J, Allen G, Courchesne E. Face processing occurs outside the fusiform ‘face area’ in autism: evidence from functional MRI. Brain. 2001 October;124(Pt 10):2059–73. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.10.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rojas DC, Smith JA, Benkers TL, Camou SL, Reite ML, Rogers SJ. Hippocampus and amygdala volumes in parents of children with autistic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 November;161(11):2038–44. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumann CM, Hamstra J, Goodlin-Jones BL, et al. The amygdala is enlarged in children but not adolescents with autism; the hippocampus is enlarged at all ages. J Neurosci. 2004 July 14;24(28):6392–401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1297-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparks BF, Friedman SD, Shaw DW, et al. Brain structural abnormalities in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Neurology. 2002 July 23;59(2):184–92. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalton KM, Nacewicz BM, Johnstone T, et al. Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nat Neurosci. 2005 April;8(4):519–26. doi: 10.1038/nn1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadjikhani N, Joseph RM, Snyder J, Tager-Flusberg H. Abnormal activation of the social brain during face perception in autism. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007 May;28(5):441–9. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang AT, Dapretto M, Hariri AR, Sigman M, Bookheimer SY. Neural correlates of facial affect processing in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004 April;43(4):481–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castelli F, Frith C, Happe F, Frith U. Autism, Asperger syndrome and brain mechanisms for the attribution of mental states to animated shapes. Brain. 2002 August;125(Pt 8):1839–49. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gervais H, Belin P, Boddaert N, et al. Abnormal cortical voice processing in autism. Nat Neurosci. 2004 August;7(8):801–2. doi: 10.1038/nn1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JS, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Conscious and unconscious emotional learning in the human amygdala. Nature. 1998 June 4;393(6684):467–70. doi: 10.1038/30976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelphrey KA, Morris JP, McCarthy G. Neural basis of eye gaze processing deficits in autism. Brain. 2005 May;128(Pt 5):1038–48. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adolphs R, Gosselin F, Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Schyns P, Damasio AR. A mechanism for impaired fear recognition after amygdala damage. Nature. 2005 January 6;433(7021):68–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasson N, Tsuchiya N, Hurley R, et al. Orienting to social stimuli differentiates social cognitive impairment in autism and schizophrenia. Neuropsychologia. 2007 June 18;45(11):2580–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adolphs R, Tranel D. Amygdala damage impairs emotion recognition from scenes only when they contain facial expressions. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41(10):1281–9. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charman T, Swettenham J, Baron-Cohen S, Cox A, Baird G, Drew A. Infants with autism: an investigation of empathy, pretend play, joint attention, and imitation. Dev Psychol. 1997 September;33(5):781–9. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clifford SM, Dissanayake C. The Early Development of Joint Attention in Infants with Autistic Disorder Using Home Video Observations and Parental Interview. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007 October 5; doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawson G, Munson J, Estes A, et al. Neurocognitive function and joint attention ability in young children with autism spectrum disorder versus developmental delay. Child Dev. 2002 March;73(2):345–58. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawson G, Toth K, Abbott R, et al. Early social attention impairments in autism: social orienting, joint attention, and attention to distress. Dev Psychol. 2004 March;40(2):271–83. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osterling J, Dawson G. Early recognition of children with autism: a study of first birthday home videotapes. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994 June;24(3):247–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02172225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yirmiya N, Gamliel I, Pilowsky T, Feldman R, Baron-Cohen S, Sigman M. The development of siblings of children with autism at 4 and 14 months: social engagement, communication, and cognition. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006 May;47(5):511–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron-Cohen S. Perceptual role taking and protodeclarative pointing in autism. Br J Dev Psych. 1989 June;7(2):113–27. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sigman M, Mundy P, Sherman T, Ungerer J. Social interactions of autistic, mentally retarded and normal children and their caregivers. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1986 September;27:647–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999 October;2(10):861–3. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munson J, Dawson G, Abbott R, et al. Amygdalar volume and behavioral development in autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 June;63(6):686–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hazlett HC, Poe MD, Gerig G, Smith RG, Piven J. Cortical gray and white brain tissue volume in adolescents and adults with autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 January 1;59(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fombonne E. Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: an update. J Aut Dev Disord. 2003;33 (4):365–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1025054610557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24 (5):659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000 June;30(3):205–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mullen EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning AGS Edition. American Guidance Service, Inc; USA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicche HV. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-Interview Edition Survey Form Manual. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service, Inc; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodfish JW, Symons FJ, Parker DE, Lewis MH. Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30 (3):237–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1005596502855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosconi MW, Mesibov G, Reznick SJ, Piven J. The Social Orienting Continuum and Response Scale: a dimensional measure for preschool-aged children [published online July 22, 2008] J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(2):242–250. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0620-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross AK, Hazlett HC, Garrett NT, Wilderson C, Piven J. Moderate sedation for MRI in young children with autism. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:867–871. doi: 10.1007/s00247-005-1499-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chappell J, Hazlett H, Piven J. Behavioral training of young children for MRI. Poster presented at the International Meeting for Autism Research (IMFAR); May 5, 2005; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Cody Hazlett H, Gimpel Smith R, Ho S, Gee JJ, Gerig G. User-Guided 3D Active Contour Segmentation of Anatomical Structures: Significantly Improved Efficiency and Reliability. NeuroImage. 2006;31:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stanfield AC, McIntosh AM, Spencer MD, Philip R, Gaur S, Lawrie SM. Towards a neuroanatomy of autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Eur Psychiatry. 2007 August 30; doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breiter HC, Etcoff NL, Whalen PJ, et al. Response and habituation of the human amygdala during visual processing of facial expression. Neuron. 1996 November;17(5):875–87. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calder AJ, Lawrence AD, Young AW. Neuropsychology of fear and loathing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001 May;2(5):352–63. doi: 10.1038/35072584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gothard KM, Battaglia FP, Erickson CA, Spitler KM, Amaral DG. Neural responses to facial expression and face identity in the monkey amygdala. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1671–1683. doi: 10.1152/jn.00714.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morton J, Johnson MH. CONSPEC and CONLERN: a two-process theory of infant face recognition. Psychol Rev. 1991 April;98(2):164–81. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.98.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amaral DG. The amygdala, social behavior, and danger detection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1000:337–347. doi: 10.1196/annals.1280.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bauman MD, Lavenex P, Mason WA, Capitanio JP, Amaral DG. The development of social behavior following neonatal amygdala lesions in rhesus monkeys. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:1388–1411. doi: 10.1162/0898929042304741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultz RT. Developmental deficits in social perception in autism: the role of the amygdala and fusiform face area. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005 April;23(2–3):125–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schultz RT, Gauthier I, Klin A, et al. Abnormal ventral temporal cortical activity during face discrimination among individuals with autism and Asperger syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000 April;57(4):331–40. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]