Abstract

Objectives

This paper documents the effects of increasingly restrictive immigration and border policies on Mexican migrant workers in the United States.

Methods

Drawing on data from the Mexican Migration Project we create a data file that links age, education, English language ability, and cumulative U.S. experience in three legal categories (documented, undocumented, guest worker) to the occupational status and wage attained by migrant household heads on their most recent U.S. trip.

Results

We find that the wage and occupational returns to various forms of human capital generally declined after harsher policies were imposed and enforcement dramatically increased after 1996, especially for U.S. experience and English language ability.

Conclusion

These results indicate that the labor market status of legal immigrants has deteriorated significantly in recent years as larger shares of the migrant workforce came to lack labor rights, either because they were undocumented or because they held temporary visas that did not allow mobility or bargaining over wages and working conditions.

Circular migration between Mexico and the United States historically has been very common. For most Mexicans, migration north of the border was not a once-in-a-lifetime event, but a mobility strategy repeated multiple times over the course of a migratory career, with trips for wage labor abroad being interspersed with stays at home. As a result, Mexican migrants accumulate U.S. experience across a number of different trips and, potentially, in a variety of different legal statuses. Although some migrants may hold the same legal status on each trip, others shift documentation over time. For example, a migrant might initially cross the border without documents to work without authorization, return home, and then reenter later with a temporary work visa, only to return home again to marry someone who can sponsor them for permanent resident status, and then come back again as a legal permanent resident. Indeed, given the proximity of Mexico to the United States and the long history of migration between the two countries, the typical Mexican immigrant is likely to have made multiple trips and accumulated different amounts of U.S. experience in several legal statuses.

We began this work seeking to determine whether U.S. labor market experience accumulated in undocumented versus temporary or permanent legal status had long-term implications for the jobs attained and wages earned by legal Mexican migrants. We hypothesized that time accumulated in undocumented or temporary status might not carry the same benefits and returns as time accumulated in permanent resident status. Compared with documented migrants, those without documents and those holding temporary work visas are constrained in the sorts of jobs they can obtain and are in a poor position to bargain for wages. Undocumented migrants are generally confined to the lowest rungs of the secondary labor market and have no effective labor rights. Likewise, temporary work visas are issued to employers rather than workers, thus constraining job mobility, skill formation, and wages and giving them very limited labor rights.

In order to consider whether experience accumulated under legal auspices had long term consequences for immigrant earnings, we turned to data from the Mexican Migration Project, which contains complete migratory histories for all household heads with U.S. migratory experience. Using these data, we selected all migrants who had achieved legal status by the time of their last U.S. trip and then identified the different pathways to legalization the migrants had followed (the sequences of statuses held prior to adjustment) and computed the cumulative time spent in different legal statuses. We then matched the pathways and accumulated times with information on wages earned on the most recent U.S. trip.

Analyzing these data, we found that, other things equal, the specific pathway a migrant followed to legalization had no effect on wages earned or occupations held after legal status was achieved. When we examined differences by legal status in the economic returns to U.S. experience, however, we found complex interactions with period of migration and discovered a sharp break in how human capital of all kinds was rewarded before and after 1996. Before that date, migrants with more education, greater English language ability, and higher levels of U.S. experience were more likely to attain a skilled occupation, whether the experience was in undocumented or temporary status. Afterward, the positive effect of education declined, English language lost its effect on occupational attainment, undocumented experience declined to insignificance, and experience accumulated with a temporary visa came to have a negative effect on the odds of getting a skilled job. In terms of wages, we observed similar differences in the returns to education, English language ability, and U.S. experience before and after 1996.

We argue here that major shifts in U.S. immigration and border policies during the mid-1990s undermined the labor market position of Mexican immigrants to the United States, even those with legal documents, the group we focus on here. We present data documenting the dramatic nature of American policy shifts and consider their likely influence on immigrant labor markets. We then estimate regression equations to predict occupational and wage attainments before and after 1996 to reveal a very clear deterioration in the labor market position of legal immigrants who, in theory, but apparently not in practice, enjoy full labor rights in the United States.

THE SHIFT IN ENFORCEMENT REGIMES

U.S. immigration policy actually began shifting in a hardline direction a decade before 1996, when congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act, which increased support for border enforcement and criminalized the hiring of unauthorized migrants. After that date, the Border Patrol increased markedly in size in a way that departed from historical trends, and employers caught hiring undocumented migrants were subject to new legal sanctions. In their analysis of data compiled through the late 1990s, Massey, Durand, and Parrado (1999) concluded that a “new era” of Mexican migration had begun in 1986, and Massey, Durand, and Malone (2002) documented in some detail the features of this new era: continued in-migration, reduced out-migration, geographic diversification of destinations, a shift from circulation to settlement, and a marginalized labor market position.

In retrospect, however, the “militarization” of the border that many saw in the wake of IRCA’s passage in 1986 (see Dunn 1996; Rotella 1998; Andreas 2000) proved to be nothing compared to what came later. In addition, the negative labor market effects of expanded enforcement were obscured by the remarkable economic boom of the 1990s, which by the end of the decade produced full employment and rising real wages (Stiglitz 2003). Although truly massive increases in immigration enforcement would come later, even in the late 1990s there were signs that all was not well for immigrants in U.S. labor markets, as the wage premium enjoyed by documented migrants before 1986 never returned despite the boom (Massey, Durand, and Malone 2002). In addition, the returns to various forms of human capital generally fell despite the modest rise in wages overall (Phillips and Massey 1999; Aguilera and Massey 2004; Massey and Gelatt 2010).

The recession of 2000 brought an end to the “roaring nineties,” of course, and wage growth once again stagnated and unemployment rose. Shortly thereafter the events of September 11 brought about a new surge in xenophobia that was quickly translated into harsher anti-immigrant policies. The hardening of immigration policies after 9/11 built on a trend that began in the 1990s. In 1993, for example, the U.S. Border Patrol launched Operation Blockade in El Paso and in 1994 it unveiled Operation Gatekeeper in San Diego, all-out militarizations of the two busiest border sectors (Andreas 2000). The policy of militarization was later extended to the rest of the border under President Clinton’s policy of “prevention through deterrence” (Massey Durand, and Malone 2002; Spenner 2010).

In 1996 Congress passed three remarkable pieces of anti-immigrant legislation that dramatically changed the playing field for immigrants. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act funded the hiring of thousands of new Border Patrol Agents and the construction of an extended border fence while authorizing the removal of aliens without judicial review, declaring undocumented migrants ineligible for public benefits, and establishing a mechanism to deputize local police departments to assist in immigration enforcement (Newton 2008). At the same time, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act placed new restrictions on the access of legal immigrants to means tested benefits and the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act declared any alien who had ever committed a crime, no matter how long ago, to be subject to deportation. It also gave federal authorities broad new powers for the “expedited exclusion” of aliens, granted the executive branch authority to exclude members of any organization it deemed to be “terrorist,” narrowed the grounds for claiming asylum, added alien smuggling to the list of crimes covered by the RICO statute (Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organizations—a law usually applied to combat the Mafia), and severely limited the judicial reviews of deportation orders (Legomsky 2000).

Finally, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11 Congress passed, without debate, the USA PATRIOT Act, which granted executive authorities even greater power to deport, without any hearing or presentation of evidence, all aliens—legal or illegal, temporary or permanent—that the Attorney General had “reason to believe” might commit, further, or facilitate acts of terrorism. This legislation was followed in 2004 by the 2004 National Intelligence Reform Act, which increased the number of border patrol agents by 20%, expanded the number of immigration investigators, and authorized funding for more immigration detention centers, air patrols, and enforcement materiel.

These federal laws were insufficient, however, to placate the anti-immigrant hysteria that arose in the wake of 9–11 and state and local politicians increasingly implemented their own anti-immigrant measures (Hopkins 2008). According to the National Council of State Legislatures (2009), the number of state laws related to immigration rose substantially after 9/11, going from 200 bills introduced and 38 laws enacted in 2005 (when record-keeping began) to 562 bills introduced and 240 laws passed in 2007. In addition, by 2009 23 states had signed cooperative agreements with federal authorities to assist in arresting and detaining unauthorized migrants.

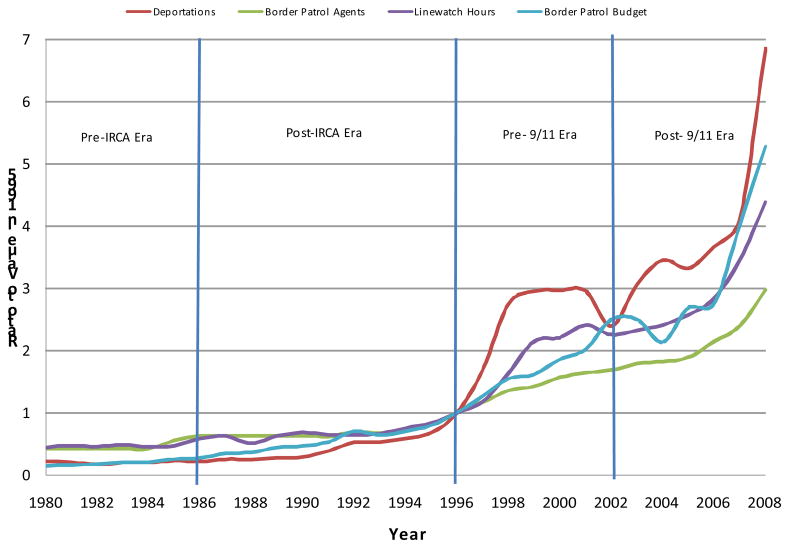

The dramatic nature of the crackdown on immigrants is indicated by Figure 1, which uses data from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2010) to show trends in the size and budget of the U.S. Border Patrol, the number of deportations from the United States, and the number of hours spent patrolling the Mexico-U.S. border (linewatch hours) from 1980 through 2008. Each series is divided by its value in 1996, so that the chart shows the factor by which enforcement has increased since that date. We divide the period into four eras corresponding roughly to four different enforcement regimes.

Figure 1.

Changes in the Mexico -U.S. migration regime 1980–2008.

As can be seen, trends are flat through early 1990s, and then began to increase slowly up to 1996, after which all of the series jump dramatically before reaching a brief plateau around the year 2000. After 2001, however, each series resumed its upward climb at an accelerated, indeed exponential rate. By 2008, the number of Border Patrol Agents had tripled compared with 1996, linewatch hours had more than quadrupled, the Border Patrol Budget had quintupled, and the number of deportations from within the United States had increased by a factor of seven. The scale of the new enforcement is indicated by the fact that in 2008 some 960,000 persons were arrested at the border, 359,000 were deported from the U.S. interior (247,000 from Mexico alone), and 320,000 were detained while awaiting trial or deportation (Massey, Durand, and Pren 2009).

CONSEQUENCES OF ENFORCEMENT

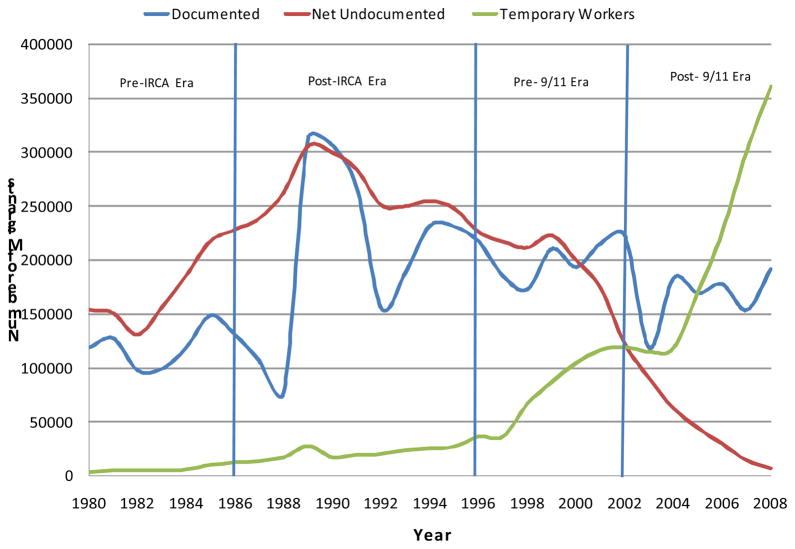

The “new era” of Mexican migration described by Massey, Durand, and Malone (2002) came about because border militarization in El Paso and San Diego channeled migration away from traditional receiving areas while reducing the rate of return migration but had little effect on undocumented entry. As a result, the number of unauthorized migrants in the United States grew rapidly and spread geographically during the 1980s and 1990s. As Figure 2 indicates, however, circumstances had changed once again by the end of the 1990s, too late for Massey et al. to detect (their data stopped in 1998). Figure 2 shows the number of legal immigrants and temporary workers entering the United States annually from Mexico (using data from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2010) plus an estimate of net undocumented migration derived by Massey, Durand and Pren (2009), who computed annual probabilities of departure and return from a first undocumented trip using data from the Mexican Migration Project and applied them to annual population counts from the Mexican Census.

Figure 2.

Mexican Migration to the United States by Legal Status

In the early 1980s, legal immigration ran between 100,000 and 125,000 per year and undocumented migration stood at around 150,000 per year. By 1986, when IRCA was passed, undocumented migrant had risen to around 225,000 per year and documented migration to around 150,000. Despite the increase in border enforcement set in motion by IRCA, however, net undocumented migration continued to rise, reaching a peak of 300,000 per year in 1989 before falling slightly and stabilizing at around 250,000 per year during the period 1992–1995. Legal immigration, meanwhile, surged to more than 300,000 persons per year as former undocumented migrants who had legalized under IRCA sponsored the entry of dependent family members.

From 1980 to 1996, guest worker migration rose gradually, with the number of Mexicans entering on temporary work visas going from 3,000 to 36,000 persons per year—a tenfold increase to be sure, but in absolute terms still only a shift of 33,000 persons per year over 16 years. Despite the restrictive immigration acts passed in 1996, annual documented and undocumented migration continued apace through the end of the 1990s, fluctuating around 200,000 persons. What changed most dramatically during the 1990s was guest worker migration. With little fanfare or public awareness, the number of temporary workers entering the U.S. from Mexico rose from 36,000 in 1996 to 116,000 in 2001, more than offsetting the slight decline in undocumented migration observed over the same period (which dropped from 226,000 to 174,000).

As border enforcement and internal deportations increased exponentially after 9/11 and as the economy faltered and then collapsed after 2007, undocumented migration fell sharply and reached near-zero levels by 2008 for the first time in nearly half a century. As in the pre-9/11 era, however, the decline in undocumented migration was more than offset by an increase in temporary labor migration. As was true historically, what changed over time was not so much the size of the inflow from Mexico, but the legal category in which the migrants entered. From 2000 to 2008, legal immigration fluctuated between 150,000 and 200,000 persons per year while undocumented migration fell from 200,000 to 7,000 persons but guest worker migration rose from 104,000 to 361,000. As a result, according to the trends summarized in Figure 2, of the nearly 500,000 Mexicans who entered the United States in 2000, 39% were documented, 40% were undocumented, and 21% were guest workers, whereas by 2008 of the 560,000 migrants entering the United States, 34% were documented, but only 1% were undocumented and 65% were guest workers.

The remarkable drop in undocumented migration is confirmed by independent calculations prepared by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which estimated that the undocumented population rose from 8.5 million to 11.8 million persons from 2000 to 2007, but thereafter began to trend downward, falling to 11.6 million persons in 2008 and 10.8 persons million in 2009 (Hoeffer, Tytina, and Baker 2010). If these figures are correct, then around 60% of all Mexicans living in the United States currently lack documents and, hence, labor market rights; and of those entering from Mexico each year, the vast majority are temporary workers who, while legal, are not in a position to bargain for better wages or working conditions.

Although stricter border enforcement was intended to choke off the supply of Mexican workers, this is not what happened. Stricter border policies reduced the rate of return migration while the rate of undocumented entry changed little, yielding an increase in the net inflow and an acceleration in the growth of the undocumented population (Massey, Durand, and Malone 2002; Massey, Durand, and Pren 2009; Massey and Riosmena 2010). Harsher anti-immigrant policies, meanwhile, pushed legal permanent residents to naturalize in record numbers; and as citizens they were able to sponsor the entry of spouses, children, and parents without numerical limit, maintaining the level of documented migration. Finally, as enforcement accelerated exponentially after 9/11 and rates of net undocumented migration finally did decline, guest worker migration was expanded dramatically to offset drop in unauthorized migration.

Through 2008, at least, there was no decline in the supply of Mexican migrant workers, but the flows were channeled increasingly into either undocumented or temporary legal statuses. As a result, since the middle 1990s Mexican workers increasingly have had to compete in labor markets where most workers either lack labor rights entirely (those without documents) or have rights that are severely constrained (those with temporary work visas), and in which immigrants of all kinds are under increasing pressure from state, local, and federal authorities. In addition, since 1986 employers have increasingly shifted from direct hiring to labor subcontracting to evade sanctions under IRCA, which is also associated with diminished bargaining power on the part of immigrants, leading to lower wages and diminished returns to human capital (Phillips and Massey 1999; Aguilera and Massey 2004).

DATA AND METHODS

Our data come from the Mexican Migration Project (MMP), a unique source of data on documented and undocumented migration to the United States that employs a blend of survey and ethnographic methods on both sides of the border to compile detailed information on migration-related variables at the individual, household, and community levels. MMP data are collected in places of different sizes, including large metropolitan areas, medium-size cities, small towns, and rural villages in regions throughout Mexico. Within each city, town, or village the researchers delimit a survey site, or community, and each year select 4–6 cities and corresponding communities for study. These communities vary in terms of ethnic composition, geographic location, and economic structure. Within cities, communities are typically neighborhoods whereas in rural villages they generally include the entire municipality.

At each site the fieldwork team creates a sampling frame by enumerating all dwellings and from the resulting list they draw a random sample of potential dwellings to be visited to determine whether they contain residents. Among those dwellings that prove to be inhabited, around 200 households are interviewed within each community, yielding a representative sample of the community. Interviewing is generally done in the winter months when seasonal migrants are home from the United States. In the course of surveying households in Mexico, interviewers are instructed to gather contact information for family members living in the United States who no longer return with any regularity. During the summer following each winter’s survey, interviewers go to U.S. destination areas and use this information to survey settled migrants, and from them gather the names and contact information for other migrants from the same community who live nearby, thereby compiling a snowball sample of permanent out-migrants.

Generally the U.S. sample is about 10% of the size of the Mexican community sample. Complete information on sampling, questionnaire construction, fieldwork methods, variable construction, and data files may be obtained from the project website at http://mmp.opr.princeton.edu/. Although these data cannot be assumed to be representative of all Mexicans or migrants in general, systematic comparisons between data on U.S. migrants identified in the MMP and nationally representative surveys suggest that the MMP offers a relatively accurate and valid profile of migrants to the United States (Massey and Zenteno 2000; Massey and Capoferro 2004).

For this analysis we draw on data gathered in 104 communities surveyed between 1987 and 2008. The MMP questionnaire includes a complete history of migration and border crossing for all household heads from the age of school-leaving to the survey date. This history records the duration and legal status of each trip to the United States and from these data we selected 1,553 male household heads who had taken at least one trip to the United States and were legal residents or U.S. citizens at the time of their last trip. These data enabled us to compute the amount of U.S. experience accumulated in different legal statuses: undocumented, documented, and temporary. Temporary legal workers are differentiated from permanent legal resident aliens and citizens because the latter two groups have full labor rights and freedom of mobility within the United States, whereas the former group does not. We then matched the experience variables with information on other personal characteristics and wages earned and jobs held on the last U.S. trip, which was compiled for all household members. The latter information was gathered for all household members, but only heads contributed the complete migration histories that we needed to identify pathways and cumulative migrant experience. Prior work using the MMP data have shown that whereas migrants cannot easily recall the wages they earned on each and every trip to the United States, they are able to recall those earned on their first and last trips with considerable accuracy and internal consistency with other variables (Massey 1987; Massey et al. 1987; Donato, Durand, and Massey 1992).

We use ordinary least squares (OLS) and logistic regression models to estimate the effect of key independent variables on occupational attainment and earnings on the last U.S. trip. Table 1 defines the variables used in our analysis. The two outcome variables are whether or not the migrant held a skilled occupation at the time of the last U.S. trip, and the amount earned per hour on the last U.S. trip, expressed in 2009 dollars. These outcomes are predicted as a function of human capital, cumulative U.S. experience, trip characteristics, and social capital in two periods: pre-1997 and post-1996. Human capital is assessed in terms of age, education, and English language ability, and U.S. experience is broken down into that accumulated under one of three different legal statuses. Cumulative time spent in documented status includes time spent in the United States as a legal resident alien, naturalized citizen, Silva Letter holder, or refugee (though the overwhelming majority accumulated time as legal resident aliens). Cumulative time in undocumented status includes time spent in the United States after an unauthorized border crossing or using a tourist visa that was violated by remaining longer than three months or taking a U.S. job. Cumulative time in temporary worker status includes time spent in the United States as a Bracero, H2A worker, or other temporary legal worker.

Table 1.

Variables used in analysis of occupations attained and wages earned by legal Mexican immigrants to the United States.

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Outcomes | |

| Skilled Occupation | Whether Professional, Skilled Manual, or Skilled Service Worker on Last U.S. Trip |

| Wage Earned | Constant 2009 Dollars Earned per Hour on Last U.S. Trip |

| Human Capital | |

| Age | Age at Time of Last U.S. Trip |

| Education | Years of Schooling Completed by Last U.S. Trip |

| English Ability | Ability on Last Trip Coded as: Neither Speaks Nor Understands (Reference); Does Not Speak But Understands Some; Speaks and Understands Some; Does Not Speak But Understands Much; Speaks and Understands Much |

| Cumulative U.S. Experience | |

| In Documented Status | Total Years Spent in U.S. in Legal Status |

| In Undocumented Status | Total Years Spent in U.S. in Unauthorized States |

| In Temporary Status | Total Years Spent in U.S. with Temporary Work Visa |

| Trip Characteristics | |

| Age at First Trip | Age at Time of First U.S. Trip |

| Number of Prior Trips | Number of Trips Before Last U.S. Trip |

| Social Capital | |

| Parent a Migrant | Parent Had Migrated Prior to Last U.S. Trip |

| Sibling a Migrant | Sibling had Migrated Prior to Last U.S. Trip |

| Migrant Household | Household Had at Least One Other Migrant by Last U.S. Trip |

| Legal Household | Household Had Legal Member by Last U.S. Trip |

| Organization Member | Migrant in Sports or Social Organization on Last U.S. Trip |

| Period | |

| Pre-1997 | Last U.S. Trip in 1996 or Earlier |

| Post-1996 | Last U.S. Trip After 1996 |

Among trip characteristics, we consider the age at which the migrant took his first U.S. trip and the number of U.S. trips taken prior to the one on which the wage and occupation are observed. Given that research has shown that migrants are able to convert social connections into better jobs with (Phillips and Massey 1999; Aguilera and Massey 2004), our models also include indicators of social ties that might potentially yield social capital. Indicators available from the MMP data set include whether or not the migrant’s parent had been to the United States by the date of the last trip, whether or not a sibling had been to the United States, whether or not a member of the migrant’s household had been to the United States, whether or not the migrant’s household contained a legal resident alien, and whether or not the migrant participated in a sports or social organization in the United States, all defined as of the time of the last U.S. trip.

Table 2 presents means and standard deviations associated with the foregoing variables. As can be seen, the average migrant was aged 41 at the time of the last U.S. trip and had around 6 years of schooling with some command of the English language, either speaking or understanding some (31%) or speaking and understanding much (22%). At the time of the last trip, the large majority of migrants (70%) held unskilled jobs, including 32% in agriculture, 24% in manual labor, and 14% in services (detailed breakdown not shown). Only 30% held a skilled occupation at the time of the last trip, including 22% in manual labor, 6% in services, and 3% in some kind of profession (detail not shown). On average, respondents began migrating at around age 22 and had made a total of 5.4 trips to the United States, in the course of which they accumulated 8.6 years as documented migrants, 4.9 years as undocumented migrants, and about a third of a year as temporary labor migrants.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations for variables used in analysis of occupations attained and wages earned by legal Mexican immigrants.

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||

| Holds Skilled Occupation on Last Trip | 0.30 | 0.46 |

| Wage Earned on Last Trip | 12.56 | 8.04 |

| Human Capital | ||

| Age | 41.09 | 11.95 |

| Education | 5.99 | 3.91 |

| English Ability | ||

| Doesn’t Speak But Understands Some | 0.20 | 0.40 |

| Speaks and Understands Some | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| Doesn’t Speak But Understands Much | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| Speaks and Understands Much | 0.22 | 0.41 |

| Cumulative U.S. Experience | ||

| In Documented Status | 8.62 | 8.02 |

| In Undocumented Status | 4.92 | 5.33 |

| In Temporary Status | 0.34 | 1.67 |

| Trip Characteristics | ||

| Age at First Trip | 22.31 | 7.63 |

| Number of Prior Trips | 5.38 | 7.29 |

| Social Capital | ||

| Parent a Migrant | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Sibling a Migrant | 0.73 | 0.44 |

| Migrant Household | 0.62 | 0.49 |

| Legal Household | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| Organization Member | 0.22 | 0.41 |

| Period | ||

| Pre-1997 | 0.70 | 0.46 |

| Post-1996 | 0.30 | 0.46 |

OCCUPATIONAL ATTAINMENT IN THE NEW REGIME

In order to assess occupational attainment we estimated a logistic regression equation to predict whether or not the legal immigrant in question had attained a skilled occupation by the time of his last trip to the United States; and in order to determine whether the process of occupational attainment had shifted over time, we estimated this equation during two time periods: before 1997 and after 1996. The results of these operations are shown in Table 3. For U.S. trips taken through 1996, education and English language ability significantly raise the likelihood of holding a skilled occupation. For example, each year of education increases the odds attaining a skilled job by around 8% [exp(0.074)=1.077] and for those who speak and understand much English the odds of holding a skilled occupation are nearly three times greater compared to those who neither speak nor understand English [exp(1.023)=2.781]. When it comes to occupational achievement, understanding English seems to be more important than speaking. The odds of holding a skilled job are 2.6 times greater for someone who does not speak but understands well compared with someone who neither spoke nor understood English [exp(0.961)=2.614].

Table 3.

Effect of selected variables on the probability of holding a skilled job on the most recent U.S. trip.

| Independent Variables | Pre-1997

|

Post-1996

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Human Capital | ||||

| Age | 0.047 | 0.052 | 0.089 | 0.076 |

| Age Squared | −0.0005 | 0.0006 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

| Education | 0.074** | 0.023 | 0.062* | 0.034 |

| English Ability | ||||

| Neither Speaks Nor Understands | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Doesn’t Speak But Understands Some | 0.379 | 0.305 | 0.446 | 0.409 |

| Speaks and Understands Some | 0.473 | 0.298 | 0.242 | 0.410 |

| Doesn’t Speak But Understands Much | 0.961** | 0.365 | 0.262 | 0.418 |

| Speaks and Understands Much | 1.023** | 0.331 | 0.611 | 0.437 |

| Cumulative U.S. Experience | ||||

| In Documented Status | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.023 |

| In Undocumented Status | 0.054** | 0.021 | −0.007 | 0.026 |

| In Temporary Status | 0.048 | 0.045 | −0.172* | 0.089 |

| Trip Characteristics | ||||

| Age at First Trip | 0.056 | 0.050 | −0.106 | 0.078 |

| Age at First Trip Squared | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Number of Prior Trips | −0.083** | 0.022 | −0.105 | 0.034 |

| Social Capital | ||||

| Parent a Migrant | 0.213 | 0.183 | 0.070 | 0.256 |

| Sibling a Migrant | −0.541** | 0.206 | −0.375 | 0.239 |

| Migrant Household | 0.037 | 0.196 | 0.316 | 0.267 |

| Legal Household | 0.197 | 0.205 | −0.107 | 0.276 |

| Organization Member | 0.261 | 0.190 | −0.093 | 0.256 |

| Intercept | −3.680** | 1.104 | −1.111 | 1.715 |

| Log Likelihood | −495.872 | −260.416 | ||

| Chi-Square | 118.70** | 44.52** | ||

| Number of Migrants | 1,001 | 427 | ||

p<.10;

p<.05

Although we initially began this research assuming that experience accumulated in legal status would be more valuable than that accumulated in undocumented or temporary status, this hypothesis was not sustained. As can be seen, of all the categories of U.S. experience, the only one that is statistically significant is experience accumulated in undocumented status. Each year of additional undocumented experience raises the odds of holding a skilled job by 5.5% [exp(0.054)=1.055]. This may reflect a truncation of variance on the independent variable, as the vast majority of legal immigrants in our sample began working in the United States without authorization and accumulated considerably more experience in undocumented than documented status. Although the coefficient for temporary labor experience is not itself significant, the point estimate of 0.048 is not statistically different from that associated with undocumented experience and the lack of significance likely stems more from the limited degrees of freedom. In contrast, the coefficient for documented experience is not only insignificant, but at 0.015 it is significantly lower than that for undocumented experience (p<.05).

Of the remaining variables on the model, only number of trips and having a migrant sibling are significant in predicting the attainment of a skilled job before 1997, and both of these effects are negative. Migrants who have accumulated numerous prior trips—and thus established a pattern of seasonal back-and-forth movement for seasonal work—are generally less likely to hold a skilled occupation by the last trip. Indeed, each additional trip lowers the odds of hold a skilled job by 8% [1−exp(−0.083)=0.080]. Likewise, having a sibling with U.S. experience does not translate into occupational attainment, as migrants in this category are 42% less likely than those without migrant siblings to hold a skilled occupation [1−exp(−0.541)=0.418], an effect that is opposite in sign to what one might predict from social capital theory. While networks may easily connect migrants to jobs, they do not necessarily connect them to good jobs, especially if they are acquired through the strong tie of siblinghood (Granovetter 1983).

Up through 1996, therefore, occupational achievement was largely a function of a migrant’s human capital, with the odds of holding a skilled job rising with education, English language ability, and prior U.S. experience. In contrast, after 1996 the returns to education fell and the returns to English language ability disappeared, as did the returns to experience in undocumented status. Moreover, during a time when temporary labor migration was expanding dramatically, the returns to experience accumulated under a temporary work visa actually turned negative. After 1996, each additional year of temporary work experience lowered the odds of holding a skilled job by around 16%[1−exp(−0.172)=0.158]. No other variables had any effect on the likelihood of attaining a skilled occupation after 1996 and the fit of the model was significantly reduced, as indicated by the downward shift in the log likelihood and chi squared statistics (p<.05).

EARNINGS ACHIEVEMENT IN THE NEW REGIME

Table 4 considers the process of earnings attainment under the new enforcement regime by regressing the natural log of wages on independent variables before 1997 and after 1996 while controlling for occupational skill. The model estimated for trips taken in years up through 1996 generally follows the form of a standard wage regression. Hourly earnings rise with age during the early labor force years before peaking and falling, and the wage increases with years of education and rises with English language ability. Since the wage outcome is logged, the coefficients represent the percentage change in wages associated with a one unit change in the independent variable. Thus each additional year of schooling raises a legal migrant’s real wages by around 1.6% and those who speak and understand some English earn 13.2% more than those who speak and understand none while those who speak and understand much English earn 29.1% greater wages.

Table 4.

Effect of selected variables on the log of the wage earned on the most recent U.S. trip.

| Independent Variables | Pre-1997

|

Post-1996

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Skilled | 0.043 | 0.038 | 0.199** | 0.053 |

| Human Capital | ||||

| Age | 0.024* | 0.014 | 0.027* | 0.016 |

| Age Squared | −0.0003** | 0.0001 | −0.0004** | 0.0002 |

| Education | 0.016** | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.008 |

| English Ability | ||||

| Neither Speaks no Understands | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Doesn’t Speak But Understands Some | 0.027 | 0.046 | 0.031 | 0.086 |

| Speaks and Understands Some | 0.132** | 0.049 | 0.100 | 0.092 |

| Doesn’t Speak But Understands Much | 0.085 | 0.073 | 0.170* | 0.090 |

| Speaks and Understands Much | 0.291** | 0.067 | 0.085 | 0.104 |

| Cumulative U.S. Experience | ||||

| In Documented Status | 0.008** | 0.004 | 0.011** | 0.005 |

| In Undocumented Status | 0.009** | 0.004 | 0.015* | 0.006 |

| In Temporary Status | 0.057** | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.027 |

| Trip Characteristics | ||||

| Age at First Trip | −0.024** | 0.012 | −0.016 | 0.014 |

| Age at First Trip Squared | 0.0004* | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 |

| Number of Prior Trips | −0.009** | 0.003 | −0.005 | 0.005 |

| Social Capital | ||||

| Parent a Migrant | 0.032 | 0.034 | 0.116** | 0.058 |

| Sibling a Migrant | 0.065 | 0.047 | −0.069 | 0.059 |

| Migrant Household | 0.019 | 0.037 | −0.016 | 0.075 |

| Legal Household | 0.141** | 0.043 | 0.143** | 0.073 |

| Organization Member | 0.135** | 0.041 | 0.023 | 0.055 |

| Intercept | 1.797** | 0.224 | 1.738** | 0.337 |

| R-Squared | 0.291** | 0.202** | ||

| Number of Migrants | 877 | 365 | ||

p<.10;

p<.05

U.S. experience accumulated under documented and undocumented auspices significantly raises wages by 0.8% and 0.9% per year, respectively. Moreover, before 1997, when temporary workers were relatively scarce, experience accumulated under a temporary work visa was quite valuable, returning a wage premium of 5.7% for each additional year of temporary experience. Social capital was also important in determining wages through 1996. Coming from a household with a legal migrant raised wages by 14.1% and being a member of a social or athletic organization in the United States yielded a 13.5% return. As with occupational status, moreover, wages declined with each additional trip taken, lowering wages by around 0.9% per trip. As Massey (1987) found years ago, it is more advantageous for migrants to build up labor market experience over a small number of long trips rather than a large number of short trips. It is also better to begin migrating at a younger age. Each additional year of age was associated with 2.4% decline in earnings, though the size of the earnings penalty declined as age rose.

On trips taken after 1996, the effects of age, documented experience, and undocumented experience persist more or less as before and social capital remains important as a determinant of wages, though having a parent with U.S. experience is now significant rather than organizational membership. However, after 1996 the effect of education drops to statistical insignificance, the returns to English language ability disappear, the earnings returns to temporary labor experience drop to zero, and neither the age at first trip nor the number of trips have any significant effect on wages. Moreover, the fact that the R2 also drops from 0.29 to 0.20 suggests that, in general, individual traits are translated into wage outcomes with significantly less efficiency after 1996 (p<.05). Finally, whereas holding a skilled occupation was not important in predicting wages before 1996, afer 1997 achieving a skilled job was associated with a 20% wage premium compared with unskilled occupations.

CONCLUSION: LABOR MARKET OUTCOMES UNDER HIGH ENFORCEMENT

We began this work expecting to find that among legal Mexican migrants to the United States, work experience accumulated in undocumented or temporary status would carry fewer benefits and rewards in the labor market than experience accumulated in documented status. This hypothesis was not sustained, however. We found no evidence that U.S. experience accumulated without documents or in temporary legal status was rewarded at a lower rate than experience accumulated with legal documents. On the contrary, the occupational and earnings returns to undocumented and temporary experience appeared to equal or exceed those to documented experience, at least up through 1996. What we found instead was a sharp shift in how experience and other indicators of human capital were rewarded in U.S. labor markets before and after 1996.

This finding prompted us to reconsider the earlier work of Massey, Durand, and Malone (2002), who had linked certain migratory and labor market consequences to the rise in U.S. border enforcement taken between 1986 and 1998. By adding new data from 1998 through 2008 to the series they considered, we showed that the increases observed prior to 1996 were actually small compared to what came afterward, especially in the years after 2001. Although border enforcement did rise rapidly from 1986 to 1996, until the latter date internal enforcement was limited and guest worker migration was small. From 1996 to 2001, however, internal deportations tripled as linewatch hours doubled, while over the same period the number of temporary workers increased 3.2 times as documented and undocumented migration remained stable or declined. By 2008, internal deportations had increased to seven times their 1996 level, linewatch hours had expanded 4.4 times, and guest worker migration had risen to ten times its 1996 level. The resident population of Mexican immigrants was 60% undocumented, and two thirds of those entering each year held temporary visas with limited labor rights.

The new enforcement regime implemented after 1996 is thus characterized by heightened internal enforcement as well as expanded border enforcement, and the channeling of Mexican immigrants from undocumented into temporary legal status. Under these circumstances, the labor markets in which legal Mexican immigrants compete are dominated by people who either lack labor rights entirely (undocumented migrants) or have rights that are highly constrained (legal guest workers). As a result, we argue, after 1996 the returns to various forms of human capital deteriorated substantially. In terms of occupational attainment, the rewards to education declined and those to English language ability disappeared entirely while the returns to undocumented experience largely evaporated and those to temporary experience turned negative. In terms of wages, the returns to education also fell as those to English language ability vanished along with rewards to experience accumulated in temporary status.

While these conclusions follow from tests of significance, they do not provide a concrete sense of the substantive size of the effects. According to the point estimates reported in Table 3, before 1996 understanding much English raised the odds of holding a skilled occupation by a factor of 2.6 compared with a migrant who neither spoke nor understood any English, and speaking as well as understanding much English raised the odds by a factor of 2.8. In contrast, after 1996 the respective figures were just 1.3 and 1.8. Likewise, where the odds of achieving a skilled occupation rose by about 6% per year of undocumented experience before 1996, afterward the rate was effectively zero. Likewise, as reported in Table 4, speaking and understanding English well brought a wage premium of 29% before 1996 but just 8.5% afterward; the wage returns to each year of education fell from 1.6% to 1.2% and the returns to a year of experience as a temporary worker plummeted from 5.7% to a paltry 0.2% per year.

In sum, the position of legal Mexican immigrants in U.S. labor markets appears to have grown increasingly marginalized. Although in theory they may have full labor rights in the United States, most of the workers around them do not. Since 1996 internal enforcement has radically intensified to push Mexican workers and the bosses that employ them further underground and outside of the formal labor market; the massive expansion of border enforcement initially produced an acceleration of undocumented population growth, and although enforcement actions and economic recession finally brought an end to undocumented migration in 2008, it left a population of around 11 million unauthorized migrants marooned north of the border as temporary labor migration reached new heights. The fact that undocumented migrants have no civil or labor rights and temporary workers have severely constrained rights means that these migrants and those documented workers who compete in the same labor markets presently have few opportunities for improving wages or working conditions, especially in the context of a deep recession. In such a world, the mobility prospects of Mexican migrants are dim, even for those having the legal right to live and work in the United States.

Three decades of exponentially rising immigration and border enforcement have brought about a cessation of undocumented migration, at least in the context of a deep economic recession, but it has created a situation where the large majority of Mexican immigrant workers lack labor rights, leaving all migrants, legal as well as illegal, in an exploitable, vulnerable position. With the border now seemingly “under control,” perhaps the time has come to move forward with a broader agenda of immigration reform. Given that guest worker migration has already been expanded to record levels, the remaining goals of reform are to regularize the status of those already here and to increase the size of the annual quotas for Mexico (and Canada) to be consistent with the realities of economic integration under the North American Free Trade Agreement.

References

- Aguilera Michael B, Massey Douglas S. Social Capital and the Wages of Mexican Migrants: New Hypotheses and Tests. Social Forces. 2004;82:671–702. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas Peter. Border Games: Policing the US-Mexico Divide. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katharine M, Durand Jorge, Massey Douglas S. Changing Conditions in the U.S. Labor Market: Effects of the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. Population Research and Policy Review. 1992;11:93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn Timothy J. The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1978–1992: Low- Intensity Conflict Doctrine Comes Home. Austin: Center for Mexican American Studies, University of Texas at Austin; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter Mark. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. Sociological Theory. 1983;1:202–233. [Google Scholar]

- Heofer Michael, Rytina Nancy, Baker Bryan C. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2009. Washington, DC: Office of Immigration Statistics, U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins Daniel J. Working Paper. Center for the Study of American Politics, Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2008. Threatening Changes: Explaining Where and When Immigrants Provoke Local Opposition. [Google Scholar]

- Legomsky Stephen H. Fear and Loathing in Congress and the Courts: Immigration and Judicial Review. Texas Law Review. 2000;78:1612–20. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. Do Undocumented Migrants Earn Lower Wages than Legal Immigrants? New Evidence from Mexico. International Migration Review. 1987;21:236–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Capoferro Chiara. Measuring Undocumented Migration. International Migration Review. 2004;38:1075–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Durand Jorge, Malone Nolan J. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Age of Economic Integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Alarcón Rafael, Durand Jorge, González Humberto. Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Durand Jorge, Parrado Emilio A. The New Era of Mexican Migration to the United States. Journal of American History. 86:518–36. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Durand Jorge, Pren Karen. Nuevos Escenarios de la Migración México-Estados Unidos: Las Consecuencias de la Guerra Antiinmigrante. Papeles de Población. 2009;61:101–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Gelatt Julia. What Happened to the Wages of Mexican Immigrants? Trends and Interpretations. Latino Studies. 2010 doi: 10.1057/lst.2010.29. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Riosmena Fernando. Undocumented Migration from Latin America in an Era of Rising U.S. Enforcement. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2010;630(1):137–161. doi: 10.1177/0002716210368114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Zenteno René. A Validation of the Ethnosurvey: The Case of Mexico-U.S. Migration. International Migration Review. 2000;34:765–92. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of State Legislatures. Immigrant Policy Project: 2009 Immigration- Related Bills and Resolutions. Washington, DC: National Council of State Legislatures; 2009. Apr 22, [Accessed on June 24, 2009]. at: http://www.ncsl.org/documents/immig/2009ImmigFinalApril222009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Newton Lina. Illegal, Alien, or Immigrant: The Politics of Immigration Reform. New York: New York University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Julie, Massey Douglas S. The New Labor Market: Immigrants and Wages after IRCA. Demography. 1999;36:233–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotella Sebastian. Twilight on the Line: Underworlds and Politics at the U.S.-Mexico Border. New York: W.W. Norton; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz Joseph E. The Roaring Nineties: A New History of the World’s Most Prosperous Decade. New York: Norton; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spenner David. Clandestine Crossings: Migrants and Coyotes on the Texas-Mexico Border. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. The 2008 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, D.C: U.S. Office of Immigration Statistic, U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2010. http://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/yearbook.shtm. [Google Scholar]