Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in both developing and industrialized countries, especially among young children and in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals. It is implicated in both invasive (e.g. meningitis and septicemia) as well as noninvasive disease (community-acquired pneumonia and otitis media). The objective of the current study was to describe the overall epidemiology of both invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal disease in Abu Dhabi over a 5-year period.

DESIGN AND SETTING:

Retrospective review of all pediatric (≤ 5 year old) pneumococcal disease admissions to Shaikh Khalifa Medical City (SKMC) and Mafraq Hospital in Abu Dhabi from 1 January 2001 till 31 December 2005.th

METHODS:

We retrieved computerized data from the health information management systems (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD9) diagnosis codes) as well as manual surveillance in the laboratory record of pneumococcal isolates.

RESULTS:

The incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease was 13.6/100 000 per year (95% CI, 6.5-24.9) and the incidence of noninvasive pneumococcal disease was 172.5/100 000 per year (95% CI, 143.8-205.2). The total incidence rate was 186.0/100 000 per year (95% CI, 156.2-219.9).

CONCLUSION:

This epidemiological survey indicates that the incidence rates in the United Arab Emiratea are higher than in Western countries where conjugate pneumococcal vaccine has been introduced. This study is important as it documents the incidence of pneumococcal disease in the era before introduction of the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine and allows for future research to document the impact of a new vaccine considering the geographic variation of pneumococcal serotypes.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a gram-positive diplococcus that has become the major pathogen implicated in pediatric infections. It is implicated in both invasive (e.g. meningitis and septicemia) as well as noninvasive disease (community-acquired pneumonia and otitis media).1–4 In children younger than 18 months, it causes most bacteremia events, whether occult or symptomatic.5–8 Bacterial meningitis is usually limited to two bacteria in the immune-competent host in pediatrics past the neonatal period: S pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitides.9–11 S pneumoniae is, therefore, a major cause of mortality and morbidity in both developing and industrialized countries, especially among young children and in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals. The majority of children experience some form of pneumococcal disease before the age of 5 years.5–8

The prevalence and incidence of the S pneumoniae disease varies worldwide; it is higher in developing countries as opposed to the developed world. Mortality rates are also higher in the developing world. There are no community-based epidemiological studies of S pneumonia disease in childhood in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This would be important to document in the phase coinciding with the introduction of the streptococcal conjugate vaccine, to see the impact of vaccination success. The introduction of the Haemophilus influenza b conjugate vaccine led to two major sequelae. First, the role of pneumococcus in pediatric meningitis has become more prominent. Second, antibiotic resistance to S pneumoniae isolates are increasing worldwide. An optimal strategy for the use of the pneumococcal vaccine would be aided by having local epidemiological data in the pediatric high-risk age group of less than 5 years. The burden of pneumococcal disease in children in UAE has not been studied previously. The objective of the current study was to describe the overall frequency of both invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal disease in Abu Dhabi, UAE, over a 5-year period.

METHODS:

We conducted a retrospective review of all cases of pneumococcal diseases admitted to the pediatric wards at Shaikh Khalifa Medical City (SKMC) and Mafraq Hospital in Abu Dhabi, UAE, from the period 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2005. These are two major referral centers for pediatrics. SKMC is a 500-bed hospital and Mafraq has 300 beds. The inclusion criteria included all pediatric patients less than 5 years admitted to either of these hospitals who had invasive or noninvasive pneumococcal disease. Invasive disease was defined as an acute illness in any patient having S pneumoniae isolated from the blood or any body fluid (e.g., cerebrospinal, peritoneal, pleural, synovial). Noninvasive disease comprised patients with a probable diagnosis of community-acquired lobar pneumonia confirmed by radiological studies (lobar infiltrate) and clinical examination (crackles, fever) or laboratory markers of inflammation (either elevated acute phase markers like erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] and C-reactive protein [CRP] or white blood cells [WBC]). Finally patients admitted with a diagnosis of otitis media were also included under the category of noninvasive disease. The latter two groups are included because S pneumoniae is known to cause the large proportion of these diagnoses. We used the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD9), diagnosis codes to retrieve all the cases discharged under a list of primary diagnoses. We retrieved computerized data from the health information management systems as well as manual searching in the laboratory record of pneumococcal isolates. The exclusion criteria included all children who were above the age of 5 years, and all patients with duplicate isolates unless this was clearly a second illness and all other acutely respiratory illness as previously defined.

The laboratory technique involved standard methods previously described. Briefly, isolates were subcultured on 5% sheep blood agar and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C. α-Hemolytic colonies were identified by the optochin disc (5 μg) (Oxoid) on blood agar medium. Neither serotyping nor freezing the strains for future serotyping was undertaken.

The data were analyzed looking at the rates of the pneumococcal disease in the two hospitals, the annual rates, number of invasive and noninvasive cases, age and gender distribution, the antibiotics used, the rate of risk factors for pneumococcal disease among the patients, as well as extrapolating the annual cumulative incidence relative to the birth cohort in the year 2005. Consent for the study was attained by the Institutional Review Board at SKMC. Statistical analysis software was done with MedCalc for Windows, Version 11.2.1 (Mariakerke, Belgium). Data are described as mean and standard deviation. The incidence rate is expressed with the 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

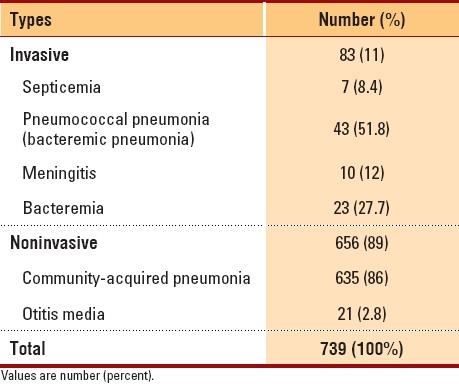

There were 739 admissions with pneumococcal disease over the 5-year study period. Of these patients, 94.5% had noninvasive disease while 5.4% had invasive disease (Table 1). More than half (57.5%) of the patients were under 2 years of age, and 75.2% of the patients were under 3 years of age; 304 (41.1%) cases were from Mafraq hospital and 435 (58.86%) from SKMC.

Table 1.

Types of pneumococcal disease.

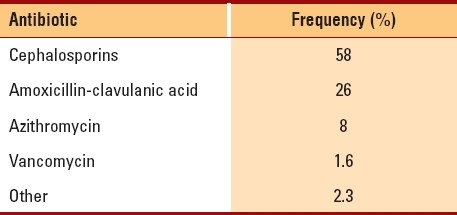

There were five deaths attributed to pneumococcal disease, all of which occurred in children less than 3 years of age. Antibiotics used in the treatment of pneumococcal disease were variable. Second- and third-generation cephalosporins and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid were used most often (Table 2). The mean (SD) length of stay for invasive and noninvasive disease was 9.1 (10.8) and 4.7 (5.8) days, respectively; 113 patients had a pre-existing medical condition recognized as creating a higher risk for pneumococcal disease. The major risk groups identified included premature infants (n=41), patients with chronic lung disease (n=24), and immunodeficient children (n=24).

Table 2.

Frequency of use of antibiotic classes.

We calculated the incidence rate of the pneumococcal disease in children 5 years old and younger for the year 2005. The emirate of Abu Dhabi represents 34.3% of the total UAE population. In 2005, the total UAE pediatric population <4.99 years was 268 369 (males: 134 544; females: 129 825). Thus, the Abu Dhabi pediatric population was 268 369×34.3%=92 050 children, of which Mafraq hospital and SKMC provide 80% coverage. Thus the denominator figure of relevance to the following statistics is 73 640 children. (Source: Census and Demographic Official State Statistics: www.tedad.ae.) Accordingly, the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease is 13.58/100 000 per year (95% CI, 6.51-24.9) and of noninvasive pneumococcal disease is 172.5/100 000 per year (95% CI, 143.8-205.2). The total incidence rate is 186.04/100 000 per year (95% CI, 156.2-219.9).

DISCUSSION

This epidemiological survey indicates that incidence rates in the UAE are higher than in Western counterparts where the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine has been introduced. To our knowledge, this is the only epidemiological study that addresses the incidence of pneumococcal disease in children under 5 years in the UAE. In North America, the reported incidence rates are 72/100 000 in southern California and 11.8-16.1 population in Canada.12,13 In Europe, the rates are 42.1 in Great Britain, 24.2 in Finland, and 10.1 population in Germany.14–16 In Australia, it is 12.7.17 Locally in Saudi, the reported rate is 3.4-53.5 population.18

Most cases occurred in immunocompetent hosts; patients with underlying predisposing conditions account for only 15.3%. Our data revealed that 1:7364 children will get invasive pneumococcal disease and 1:580 children will be afflicted by noninvasive pneumococcal disease. Therefore, it would be important for future immunization programs to encompass not only high-risk patients, but normal children as well. The other problem highlighted in this study is the extensive use of antibiotics, which globally has been linked to emerging antibiotic resistance. The major group of antibiotics used was the cephalosporins (usually second generation), probably reflecting the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, which constituted the major burden of inpatient pneumococcal disease. The disease carries significant morbidity as well as mortality and contributes to increasing length of hospital stay and utilization of resources. Most infections occurred in children less than 2 years of age, and all deaths occurred in children less than 3 years of age, highlighting the vulnerability of the young child to this infection.

This study has a number of limitations. First, it was a retrospective audit using manual and computerized search techniques and may have missed some cases. Second, the coverage for both hospitals involved accounts for about only 80% of the population. Third, serotyping was not available at the involved hospitals. Finally, the category of probable pneumonia may exaggerate the noninvasive disease in the absence of a definitive organism diagnosis.

This study is important as it documents the incidence of pneumococcal disease in the era before the introduction of the conjugated pneumococcal vaccine. The impact of a new vaccine might vary by in different regions of the world, since different pneumococcal serotypes can influence the effectiveness of the vaccine. Future research in the UAE should also be directed to study the particular serotypes of pneumococcal disease implicated locally.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klein JO. The burden of otitis media. Vaccine. 2000;19:S2–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bluestone CD, Stephnston JS, Martin LM. Ten-year review of otitis media pathogens. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:S7–11. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199208001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro AM, Bluestone CD. Otitis Media reassessed up-to-date answers to some basic questions. (79-82).Postgrad Med. 1995;97:73–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson KA, Baughman W, Rothrock G, Barrett NL, Pass M, Lexau C, et al. Epidemiology of invasive streptococcus pneumoniae infections in the united states 1995-1998: Opportunities for prevention in the conjugate vaccine era. JAMA. 2001;285:1729–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petit G, De Wals P, Law B, Tam T, Erickson LJ, Guay M, et al. Epidemiological and economic burden of pneumococcal disease in Canadian children. Can J Infect Dis. 2003;14:215–20. doi: 10.1155/2003/781794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flamaing J, Verhaegen J, Vandeven J, Verbiest N, Peetermans WE. Pneumococcal bacteremia in Belgium (1994 2004) the pre-conjugate vaccine era. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:143–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers C, Gervaix A. Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia in children. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;1:S24–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10th edition of epidemiology and prevention of vaccine preventable diseases. [Last accessed on 2008]. Available from: http//www.cdc.gov/vaccines/puls/pinkbook .

- 9.Schuchat A, Robinson K, Wenger JD, Harrison LH, Farley M, Reingold AL, et al. Bacterial meningitis in the United States in 1995. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:970–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bingen E, Levy C, Varon E, de La Rocque F, Boucherat M, d’Athis P, et al. Pneumococcal meningitis in the era of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine implementation. Eur J Clin Microbial Infect Dis. 2008;27:192–9. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0417-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dery M, Hasbun R. Changing epidemiology of bacterial meningitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2007;9:301–7. doi: 10.1007/s11908-007-0047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zangwill KM, Vadheim CM, Vannier AM, Hemenway LS, Greenberg DP, Ward JI. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in southern California: Implications for design and conduct of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine efficacy trial. J Infec Dis. 1996;174:752–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bettinger JA, Scheifele DW, Halperin SA, Kellner JD, Tyrrell G. Invasive pneumococcal infections in Canadian children, 1998-2003: Implications for new vaccine. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:111–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03404320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ispahani P, Slack RC, Donald FE, Weston VC, Rutter N. Twenty years surveillance of invasive pneumococcal disease in Nottingham: Serogroups responsible and implicated for immunization. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:757–62. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.036921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eskola J, Takala AK, Kela E, Pekkanen E. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal infections in children in Finland. JAMA. 1992;268:3323–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rückinger S, von Kries R, Reinert RR, van der Linden M, Siedler A. Childhood invasive pneumococcal disease in Germany between 1997 and 2003: Variability in incidence and serotype distribution in absence of general pneumococcal conjugate vaccination. Vaccine. 2008;26:3984–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liddle JL, McIntyre PB, Davis CW. Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in Sydney children 1991-96. J Paediatr Child Health. 1991;35:67–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shibl A, Memish Z, Pelton S. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33(410):e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]