Abstract

Neurofibromatosis is a genetically-inherited disorder of the nervous system that primarily affects the development and growth of neural (nerve) cell tissues and also causes cafe-au-lait spots on the skin, dysplastic abnormalities of the skin, nervous system, bones, endocrine organs and blood vessels. The two major classifications are NF-1, a generalized form, is the commonest and affects peripheral nerve tissues and NF-2, a rare central form, affects the central nervous system. An unusual finding of oral hamartomas may occur as part of NF-1 and here we presented one such rare case of oral hamartomas in a patient with Von-Recklinghausen's disease.

Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis type I (vRNF-1), first described by Frederick Von Recklinghausen in 1882, is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in chromosome 17.1,2 This inherited systemic disease affects approximately 1 in 3500 individuals. Typical dysplasias in NF-1 patients involve the skeletal system (sphenoid wing dysplasia, tibial pseudarthrosis), the skin (café-au-lait spots), and the nervous system (optic pathway gliomas, neurofibromas, astrocytomas, pheochromocytoma and meningeomas).

CASE

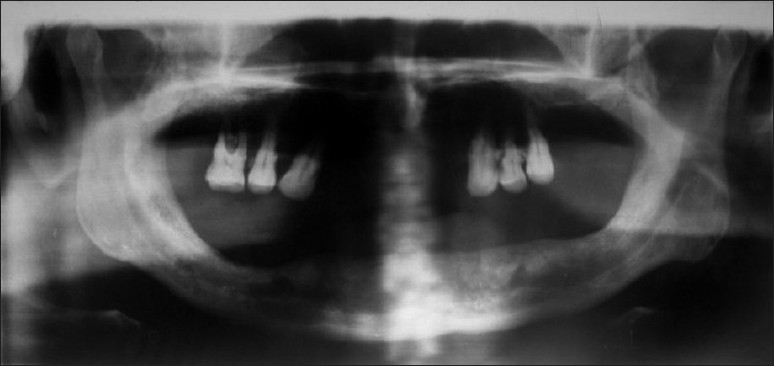

A 65-year-old male reported to the Department of Oral Medicine with a chief complaint of multiple nodules of varying size all over the body and also in the mouth for the previoux 30 years. The patient admitted that initially the small nodule appeared on his back and then gradually increased in size with development of other nodules all over the body including the mouth, which was occasionally associated with an itching sensation. The patient had no relevant medical history. On examination the nodules were either sessile or pedunculated, with a smooth surface of varying size ranging from millimeters to centimeters with normal skin color, soft to firm, non tender and present over the whole body. Yellowish-tan to dark-brown macules were also noticed in the vicinity of the nodules, which were smooth-edged and varied in diameter from 1 to 2 millimeter to several centimeters (café-au-lait spots). An ocular examination performed by an ophthalmologist for Lisch nodules using a slit lamp test was positive. Intra-oral examination revealed the presence of multiple nodules in the anterior part of the hard palate of variable size and normal mucosal color, soft to firm in consistency, nonulcerated and nontender (Figure 1) and the presence of macroglossia. Radiographical examination revealed no contributory finding by periapical and occlusal radiographs. A panaromic radiograph revealed widened mandibular canals with bifurcation in the premolar region, pathognomic of neurofibromatosis type I (Figure 2). A sample of tissue taken from the intraoral palatal nodule was sent for histopathological tissue examination. It revealed that the dermis and subcutaneous tissue had diffuse spindle cell tumors composed of cells with tapering ends and wavy nuclei. There was evidence of pleomorphism or mitosis suggestive of neurofibromatosis.

Figure 1.

Nodular or neurofibromatous growths of palate and alveolar ridge.

Figure 2.

Orthopantomogram showing widened mandibular canals bilaterally along with bifurcation in premolar region.

On the basis of history, clinical and radiologically evidence along with the histopathological investigation, the case was diagnosed as von Recklinghausen disease.

DISCUSSION

Neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1), commonly known as von Recklinghausen disease, is a human genetic disorder caused by a single gene.There is no racial, gender or age predilection for the development of oral neurofibromas in NF-1.1 NF-1 is a tumor disease that is caused by the malfunction of a gene on chromosome 17 that is responsible for control of cell division. It often presents with scoliosis (bone disease) and eye problems.3,4

NF-1 is caused by a mutation of a gene on the long arm of chromosome 17 that encodes a protein known as neurofibromin, which plays a role in intracellular signaling. Neurofibromin regulates many of the pathways responsible for overactive cell proliferation, learning impairments, skeletal defects and plays a role in neural development. Neurofibromin is a negative regulator of the Ras oncogene. The mutant gene is transmitted with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, but up to 50% of NF-1 cases arise due to spontaneous mutation. The incidence of NF-1 is about 1 in 3500 live birth.5 A neurofibromatosis is a mass lesion of the peripheral nervous system. Its cellular lineage is uncertain, and may derive from Schwann cells, other perineural cell lines, or fibroblasts.6

A cutaneous neurofibroma manifests as a solitary or as multiple firm, as rubbery bumps of varied size on the skin and their presence in the oral cavity is very rare. The hallmark lesion of NF-1 is the plexiform neurofibroma.7 Malignant peripheral nerve-sheath tumor, commonly known as neurofibrosarcomas, can arise from degeneration of a plexiform neurofibroma, but this is a rare complication,8 with a lifetime risk of 8% to 12% of transformation neurofibroma. Patients with NF-1 develop flat pigmented lesions of the skin called cafι au lait spots and also freckles of the axillae (Crowe sign). Intracranially, NF-1 patients have a predisposition to develop glial tumors of the central nervous system, primarily optic gliomas. Lisch nodules (dome-shaped, pigmented nodules of the iris) are present in 90% of type 1 patients at the age of 5 years. Other significant dysplasias in NF-1 patients involve the skeletal system (sphenoid wing dysplasia, tibial pseudoarthrosis) and the nervous system (optic pathway gliomas, neurofibromas, astrocytomas, pheochromocytoma and meningeomas).9,10

Radiographically, oral neurofibromas present with a wide mandibular canal, mandibular foramen and mental foramen. Neurofibromas may seldom be primarily intraosseous; in that case they usually appear as a unilocular, with a well-defined radiolucency. Most neurofibromas show low attenuation in CT scans, although some of them may show soft tissue density. Low-density lesions contain a variable amount of Schwann cells rich in lipids, cystic degeneration and xanthomatous alterations. High-density areas are thought to represent collagen rich or cellular areas. On MRI, lesions show a low signal in T1 and a high signal in T2, with a variable highlighting with the contrast. A high peripheral signal with a low central signal in T2 weighted images (bull's eye sign) is a typical sign of neurofibromas. A similar sign can also be seen in CT.11,12

Histologically, neurofibromas are composed of a mixture of Schwann cells, perineural cells, and endoneural fibroblasts, without a capsule. Schwann cells account for about 36% to 80% of lesional cells. These constitute the predominant cellular type and they usually have widened nuclei with an undulated shape and sharp corners. On electronic microscopy, Schwann cells can be seen embracing axons. It is estimated that between 0.7% and 31% of cells are perineural cells. In seldom cases this type of cell can predominate.13

The National Institute of Health created seven specific criteria for the diagnosis of NF-1 in 1987, including six or more café-au-lait macules, two or more neurofibromas, freckling, optic glioma, two or more Lisch nodules, a distinctive osseous lesion and a first-degree relative with NF-1 by the above criteria. Two of these seven “cardinal clinical features” are required for positive diagnosis.14

There is no cure for the disease itself except for the symptomatic treatment followed by a team of specialists to manage complications. Surgery can be attempted when the tumors compress organs or other structures. Less than 8% to 12% people with neurofibromatosis develop cancerous growth; in these cases, chemotherapy could be beneficial.14 It is important that oral physicians and surgeons keep this disease under consideration when oral lesions characteristic of NF-I are present. These patients must be reviewed long term because of eventual complications, particularly malignant transformation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bongiorno MR, Pistone G, Aricò M. Manifestations of the tongue in neurofibromatosis type 1. Oral Dis. 2006;12:125–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunha KS, Barboza EP, Dias EP, Oliveira FM. Neurofibromatosis type I with periodontal manifestation. A case report and literature review. Br Dent J. 2004;196:457–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganesh S, Sharma AGM, Bhuttan S. A case of neurofibromatosis 1 presenting with optic pathway glioma with an early onset and an aggressive course. Indian J Opthalmol. 2008 Mar-Apr;56(2):161–162. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.39128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balachandran VP, Karpeh MS. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromatosis 1. Clinical observations. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker D, Wright E, Nguyen K, Cannon L, Fain P, Goldgar D, et al. Gene for von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis is in the pericentromeric region of chromosome 17. Science. 1987;236:1100–2. doi: 10.1126/science.3107130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García de Marcos JA, Dean Ferrer A, Alamillos Granados F, Ruiz Masera JJ, García de Marcos MJ, Vidal Jiménez A, et al. Gingival neurofibroma in a nurofibromatosis type 1 patient. Case report. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:287–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin V, Daniel S, Forte V. Is a Plexiform Neurofibroma Pathognomonic of Neurofibromatosis Type I? Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1410–4. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200408000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharyy I, Cohen D. Oral neurofibroma. 2006. Apr, (citado 5 junio 2006) “www.emedicine.com/derm/topic674.htm. ” .

- 9.Kim G, Mehta M, Kucharczyk W, Blaser S. Spontaneous regression of Tectal mass in Neurofibromaosis 1. AJNR Am J Neurodiol. 1998;19:1137–1139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marx RE, Stern D. Oral and maxillofacial pathology.A rationale for diagnosis and treatment. Illinois: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apostolidis C, Anterriotis D, Rapidis AD, Angelopoulos AP. Solitary intraosseous neurofibroma of the inferior alveolar nerve: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:232–5. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekisz O, Darimont F, Rompen EH. Diffuse but unilateral gingival enlargement associated with von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis: a case report. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:361–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027005361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ide F, Shimoyama T, Horie N, Kusama K. Comparative ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of perineurioma and neurofibroma of the oral mucosa. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:948–53. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Worthe S, Holt jr. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report and review of literature. Journal of Family Practice. 1992 May; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George RA, Godara SC, Som PP. Cranio-orbital-temporal neurofibromatosis: Acase report and review of literature. Neurology. 2004;14(3):317–319. [Google Scholar]