Abstract

Objective To investigate the agreement between direct and indirect comparisons of competing healthcare interventions.

Design Meta-epidemiological study based on sample of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and PubMed.

Inclusion criteria Systematic reviews that provided sufficient data for both direct comparison and independent indirect comparisons of two interventions on the basis of a common comparator and in which the odds ratio could be used as the outcome statistic.

Main outcome measure Inconsistency measured by the difference in the log odds ratio between the direct and indirect methods.

Results The study included 112 independent trial networks (including 1552 trials with 478 775 patients in total) that allowed both direct and indirect comparison of two interventions. Indirect comparison had already been explicitly done in only 13 of the 85 Cochrane reviews included. The inconsistency between the direct and indirect comparison was statistically significant in 16 cases (14%, 95% confidence interval 9% to 22%). The statistically significant inconsistency was associated with fewer trials, subjectively assessed outcomes, and statistically significant effects of treatment in either direct or indirect comparisons. Owing to considerable inconsistency, many (14/39) of the statistically significant effects by direct comparison became non-significant when the direct and indirect estimates were combined.

Conclusions Significant inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons may be more prevalent than previously observed. Direct and indirect estimates should be combined in mixed treatment comparisons only after adequate assessment of the consistency of the evidence.

Introduction

Randomised controlled trials to compare competing interventions are often lacking, and this situation is unlikely to improve in the future because of the inevitable tension between the high cost of clinical trials and the continuing introduction of new treatments.1 2 The dearth of evidence from head to head randomised controlled trials has led to increased use of indirect comparison methods to estimate the comparative effects of treatment.1 2 3 4

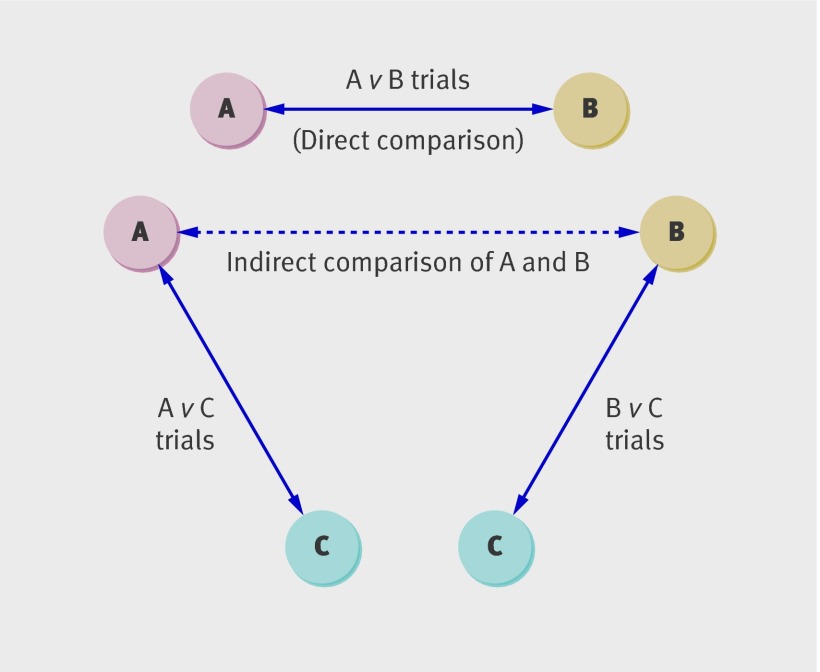

Indirect comparison of competing interventions can be generally defined as a comparison of different treatments for a clinical indication by using data from separate randomised controlled trials, in contrast to direct comparison within randomised controlled trials. Indirect comparison based on a common comparator can preserve certain strengths of randomised allocation of patients for estimating comparative effects of treatment.1 5 6 The term “adjusted indirect comparison” is used to refer to this indirect comparison based on a common intervention (fig 1).7 Mixed treatment comparison (also known as network meta-analysis or multiple treatment meta-analysis) is a more complex method that combines both indirect and direct estimates simultaneously.8 9 10 The validity of indirect and mixed treatment comparisons depends on certain basic assumptions that are similar to but more complex than assumptions underlying standard meta-analysis.1 3

Fig 1 Trial network used to investigate inconsistency between direct and indirect comparison. Each trial network consists of three sets of independent trials: one set for direct comparison of A versus B and two sets for adjusted indirect comparison of A versus B with C as common comparator.

The validity of adjusted indirect comparison has been previously investigated by systematically comparing results of adjusted indirect comparison and direct comparison by using data from published meta-analyses.7 11 The limited evidence indicated that differences between direct and adjusted indirect comparisons were only occasionally statistically significant (3/44).7 The objective of this study was to update our previous work by refining the methods used and increasing the number of cases included.7

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials that provided sufficient data for both direct and indirect comparison of two interventions (A and B). Using data from the included systematic reviews, we constructed trial networks so that interventions A and B could be compared both directly and indirectly (fig 1). Each trial network is a simple loop of evidence, consisting of three sets of independent randomised controlled trials: one for the direct comparison of A versus B and two for the indirect comparison of A versus B with C as the common comparator. We included all reviews that provided sufficient data, whether or not the indirect comparison was done in the original analysis.

In a trial network, interventions A and B are the two active interventions we would like to compare, and the common intervention C may be a placebo or no-treatment intervention. In some included trial networks, all three interventions were active interventions so that the common comparator must also be an active treatment. In these cases, we selected the comparison that provided the most precise estimate as the direct comparison (that is, the smallest standard error among the possible direct comparisons). This decision means that the direct comparison will be more likely to be statistically significant, but it has no effect on the absolute inconsistency between the direct and indirect comparison.

The use of odds ratios for binary outcomes is associated with less heterogeneity in meta-analysis than is the use of risk differences or relative risks,12 and possible inferential fallacies exist when relative risk is used in indirect comparison.13 Therefore, we included only cases in which the odds ratio could be used as the outcome statistic.

When we found multiple systematic reviews or meta-analyses on the same topic, we included only the most recent meta-analyses with the largest number of included trials. We excluded meta-analyses in which the odds ratio could not be used as the outcome statistic. We included three arm trials (comparing interventions A, B, and C within the same randomised controlled trials) only for the direct comparison of interventions A and B.

Identification of relevant trial networks

We identified most relevant cases by scanning all Cochrane systematic reviews revised or published between January 2000 and October 2008. We obtained the titles and abstracts of all completed Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (issue 3, 2008). One reviewer (SPB) scanned these titles and abstracts, and two reviewers (YKL and FS) assessed full publications of the identified possibly relevant reviews. If the indirect comparison was not explicitly done in the original review, we checked information provided in the review to identify apparent reasons why the indirect comparison was clearly inappropriate. We resolved any uncertain cases by discussion.

We also searched PubMed in October 2008 for systematic reviews or meta-analyses published since 2000 in which indirect comparison had been explicitly used (see appendix 1 in Song et al 2009 for the search strategy3). We identified additional independent cases from previous published studies.7 11

Data extraction

We extracted the following information from the included systematic reviews: disease categories, interventions compared, outcomes measured, number of trials and patients, and results of trials included in meta-analyses. One reviewer did the data extraction, and a second reviewer checked it. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or the involvement of a third reviewer if necessary.

Data analysis methods

We used Bucher et al’s method to do adjusted indirect comparisons.5 We pooled results from individual trials by using random effects, inverse variance, weighted meta-analysis (DerSimonian-Laird method14). We calculated the inconsistency, defined as the difference in log odds ratios between direct and indirect estimates, together with its standard error, and tested whether the inconsistency was statistically significant. The inconsistency between direct and indirect estimates can also be expressed as a ratio of odds ratios by an antilog transformation. Web appendix 1 gives the calculation methods and formulas used, with a practical example.

We calculated the proportion of trial networks with a statistically significant inconsistency (P<0.05) between the direct and indirect comparisons. We did pre-specified subgroup analyses to investigate the association of a significant inconsistency and certain characteristics of the comparison: source of trial networks, type of common comparators, nature of the two interventions compared, total number of trials, extent of heterogeneity in meta-analysis, whether the outcome was subjectively or objectively assessed, and the results of direct or indirect comparisons. We used the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test to statistically assess the difference between subgroups when the expected value was lower than 5.

To examine the effect of random error, we plotted the absolute value of inconsistency against the inverse of its standard error in a one sided funnel plot. We used the absolute value of inconsistency because it would usually be arbitrary to decide which of the two interventions being compared was the main treatment of interest (notated as A in the above equations) and which was considered as the active comparator (notated as B). In trial networks that compared a newer or more intense intervention to an older or less intense intervention, we considered the first to be intervention A and the second to be intervention B. Therefore, the sign (or direction) of inconsistency between the direct and indirect estimates indicates whether the indirect comparisons have overestimated or underestimated the treatment effects compared with the direct comparison. For these trial networks, we used a conventional funnel plot to examine the possible small study effect (Egger’s regression method).15

Results

After assessing the abstracts of 3319 Cochrane systematic reviews completed by October 2008, we identified 223 reviews that were possibly relevant. We then examined full publications of these 223 Cochrane reviews and included 85 independent trial networks that met the inclusion criteria. From 745 references retrieved from searching PubMed in October 2008, we included 12 systematic reviews that contained 17 independent trial networks. We also identified 10 additional trial networks from previous studies.7 11 In total, we included 112 independent trial networks. Web appendix 2 shows excluded cases with reasons for exclusion.

Web appendix 3 summarises the main characteristics of the included trial networks. The included trial networks evaluated interventions for a wide range of clinical indications (table 1). Ninety-nine of the 112 trial networks evaluated drug treatments. In total, 473 trials (with 141 363 patients) contributed data for the direct comparisons. The adjusted indirect comparisons involved 1079 trials (with 337 412 patients) (table 1). The number of trials ranged from one to 18 (median 3) per direct comparison and from two to 65 (median 6) per adjusted indirect comparison.

Table 1.

Summary of basic characteristics of included trial networks

| Characteristics | No (%) (n=112) |

|---|---|

| Total No of trials involved | |

| Direct comparison | 473 |

| Adjusted indirect comparison | 1079 |

| Source | |

| Cochrane systematic reviews | 85 (76) |

| Search of PubMed | 17 (15) |

| Previous study | 10 (9) |

| Types of interventions | |

| Drug | 99 (88) |

| Surgical | 8 (7) |

| Psycho-educational | 2 (2) |

| Educational plus drug | 1 (1) |

| Physiotherapy | 1 (1) |

| Nutritional | 1 (1) |

| Clinical field | |

| Infectious | 24 (21) |

| Circulatory | 16 (14) |

| Mental | 11 (10) |

| Gastrointestinal | 8 (7) |

| Pregnancy/childbirth | 9 (8) |

| Gynaecological | 6 (5) |

| Organ transplantation | 6 (5) |

| Neoplasm/cancer | 5 (5) |

| Dermatological | 4 (4) |

| Substance misuse/smoking | 3 (3) |

| Pain | 3 (3) |

| Other | 17 (15) |

Inconsistency between direct and indirect estimates

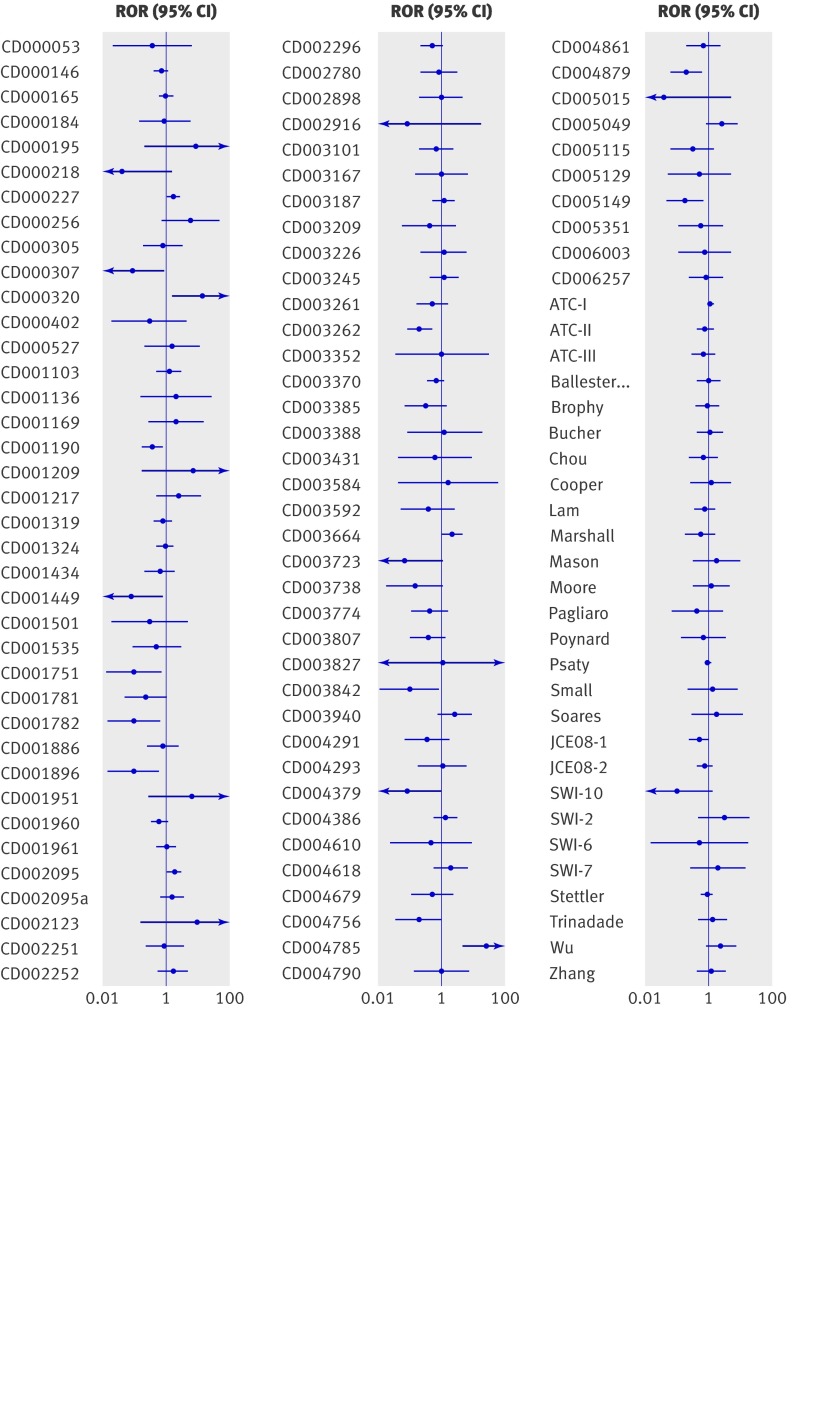

Figure 2 shows observed inconsistencies (ratio of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals) between direct and indirect comparisons. The direction of the ratio of odds ratios has no clinical meaning in many instances owing to the arbitrary labelling of interventions as A and B.

Fig 2 Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparison: ratio of odds ratios (ROR) from 112 included trial networks. ROR=1 indicates no difference in odds ratios between direct and indirect comparison

Of the 112 included trial networks, the inconsistency between the direct and indirect comparison was statistically significant (P<0.05) in 16 cases (14%, 95% confidence interval 9% to 22%). All 16 cases of significant inconsistency were from the Cochrane reviews (table 2). We found no significant difference in the frequency of significant inconsistency between subgroups according to the common comparator used, the nature of the two interventions (A and B) compared, or whether indirect comparisons had been explicitly done in the original Cochrane reviews (table 2). However, statistically significant inconsistency was associated with fewer randomised controlled trials (P=0.006), subjectively assessed outcomes (P=0.029), and statistically significant estimates of treatment effects by either direct or indirect comparison (P<0.001). The extent of heterogeneity in meta-analyses was also statistically significantly associated with the inconsistency (P=0.018), which seemed to be at least partly a result of confounding by the small number of primary studies (table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical inconsistency between direct and indirect comparison: results of overall and subgroup analyses

| Subgroups | No (%) with statistically significant inconsistency | Difference between subgroups (P value) |

|---|---|---|

| All trial networks | 16/112 (14) | |

| Source of trial networks: | 0.011 | |

| Cochrane review | 16/85 (19) | |

| Other | 0/27 (0) | |

| Common comparator: | 1.000 | |

| Placebo or no treatment | 10/67 (15) | |

| Active treatment | 6/45 (13) | |

| Nature of comparison: | 0.420 | |

| Different class/types | 7/56 (13) | |

| Same class | 4/39 (10) | |

| Same intervention | 5/17 (29) | |

| Intervention A v B: | 0.790 | |

| Newer or more intense | 10/65 (15) | |

| Unclear | 6/47 (13) | |

| Outcome measures: | 0.029 | |

| Subjective | 8/29 (28) | |

| Objective | 8/83 (10) | |

| Extent of heterogeneity*: | 0.018 | |

| I2=0 (3-5 trials) | 8/20 (40) | |

| I2=0 (≥6 trials) | 3/23 (13) | |

| I2>0, <50% | 2/31 (7) | |

| I2≥50% | 3/36 (8) | |

| Total No of trials: | 0.006 | |

| 3-5 | 8/26 (31) | |

| 6-9 | 5/27 (19) | |

| 10-14 | 3/25 (12) | |

| ≥15 | 0/34 (0) | |

| Indirect comparison in original Cochrane reviews: | 0.446 | |

| Explicitly done | 1/13 (8) | |

| Not done | 15/72 (21) | |

| Significant result by direct or indirect comparison: | <0.001 | |

| Significant | 15/48 (31) | |

| Non-significant | 1/64 (2) |

*Largest I2 among three meta-analyses in each trial network; I2 not available in two trial networks.

Thirty-nine (35%) of the 112 direct comparisons showed statistically significant results in favour of an intervention, but only 13 indirect comparisons gave the same results as the corresponding direct comparisons (table 3). In one case, the adjusted indirect comparison gave a significant result that was opposite to that of the direct comparison (see web appendix 1 for details). When we combined the direct and indirect estimates, 14 of the 39 statistically significant direct estimates were no longer statistically significant and only three of the 73 non-significant direct estimates became statistically significant (table 3).

Table 3.

Statistically significant results from direct and adjusted indirect comparisons

| Comparison methods | Direct comparisons of A and B | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Significant results (P<0.05) | Non-significant results | ||

| All trial networks | 39 | 73 | 112 |

| Indirect comparisons of A and B: | |||

| Significant results | 14* | 9 | 23 |

| Non-significant results | 25 | 64 | 89 |

| Combination of direct and indirect estimates†: | |||

| Significant results | 25 | 3 | 28 |

| Non-significant results | 14 | 70 | 84 |

*In one case (CD003262), both direct and indirect estimates were statistically significant but in opposite directions (see web appendix 1).

†DerSimonian-Laird random effects model used to combine direct and indirect estimates.

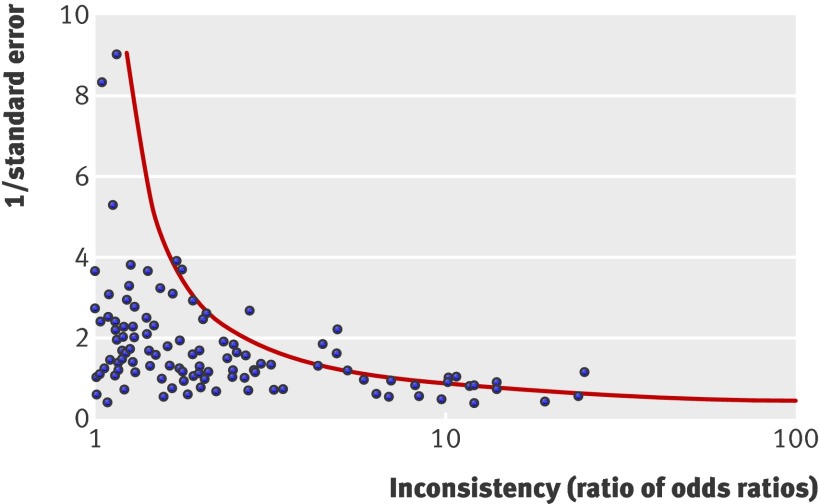

The shape of the one sided funnel plot indicates that the observed inconsistency between the direct and indirect comparisons could be explained to some extent by random error (fig 3). However, we would expect approximately 5% of the points to lie to the right of the dotted line, whereas actually 14% do.

Fig 3 One sided funnel plot of (absolute) estimated inconsistency between direct and indirect comparison. Dotted line indicates statistical significance at P=0.05

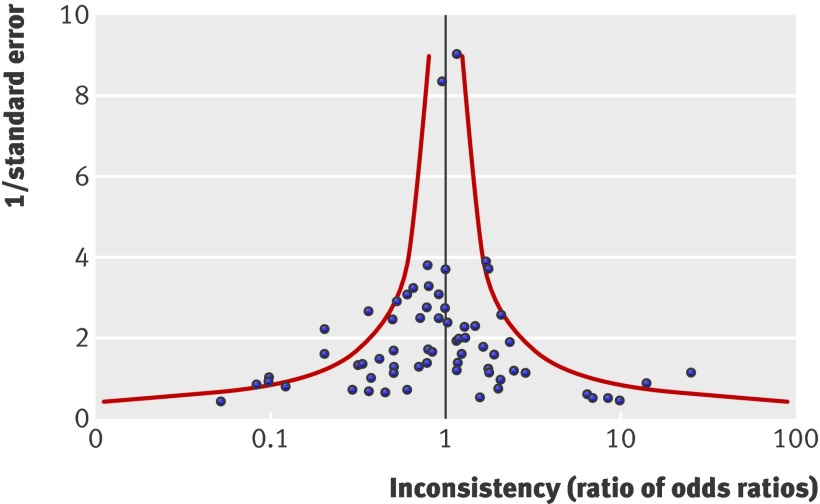

In 65 trial networks that compared a newer or more intense intervention with an older or less intense intervention, the sign (or direction) of the inconsistency between the direct and indirect estimates indicates whether the indirect comparisons have overestimated or underestimated the effects of treatment compared with the direct comparison. Figure 4 is a funnel plot of observed discrepancies between the direct and indirect comparison in these 65 cases. The funnel plot is visually symmetrical (Egger’s test, P=0.37). The pooled inconsistency (ratio of odds ratios) from the 65 cases was 0.90 (95% confidence interval 0.76 to 1.06; P=0.22), indicating that, overall, the difference between the direct and indirect estimates was not statistically different.

Fig 4 Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons of newer or more intense with older or less intense interventions. Data from 65 relevant trial networks. Ratio of odds ratios (ROR) <1 indicates that effect of newer or more intense interventions is greater in direct comparison than in indirect comparison

Discussion

Our findings indicate that significant inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons of competing healthcare interventions may be more prevalent than previously observed and may be more common with subjectively assessed outcomes, fewer trials included in analyses, and statistically significant results from either direct or indirect comparison. The proportion of cases with statistically significant inconsistency (P<0.05) between the direct and indirect comparison observed in this study was 14%, much higher than the expected 5% (statistical significance α=0.05) and higher than that found in a previous study (7%).7

Inconsistency between the direct and indirect comparisons may be explained by the play of chance, bias in the direct or indirect comparison, and clinically meaningful heterogeneity.3 The funnel plot in this study shows that the effect of random error is apparent; the points of inconsistency (ratio of odds ratios) with less precise estimates were much more widely scattered (fig 3). We found that statistical inconsistency was associated with subjectively assessed outcomes, which may be because of the greater risk of bias in trials with subjectively assessed outcomes.16

Trial networks with fewer randomised controlled trials are expected to have wider confidence intervals, so statistically significant inconsistency should be less likely. However, statistically significant results were not associated with the number of trials in the trial networks included. The proportion of statistically significant results from either direct or indirect comparisons was 42% in trial networks that included only three to five randomised controlled trials (with a median sample size of 89 per trial), and it was 43% in trial networks that included six or more randomised controlled trials (with a median sample size of 138 per trial). Therefore, the association between significant inconsistency and fewer randomised controlled trials may be partly due to the “small study effect.” Small trials are suspected to be more vulnerable to the biased selection of positive results for publication.17

As between study heterogeneity increases, so does the uncertainty in the estimated effects of treatment. This increased uncertainty means that statistically significant inconsistency is less likely to be detected. We found zero heterogeneity (I2=0) in a large number of trial networks (20/26) that included only three to five primary studies in total (table 2). Because of the small number of studies involved in many trial networks, data from this study are insufficient to show a clear pattern of association between the extent of heterogeneity and statistical inconsistency between the direct and indirect estimates.

In meta-epidemiological research, researchers often assume that bias (from methodological flaws) in clinical trials is associated with an exaggerated effect of treatment.16 18 19 Previous studies found that the treatment effects of new drugs tended to be greater when assessed by direct comparisons than with the adjusted indirect comparisons, possibly as a result of “optimism bias” or “novel agent effects.”20 21 In this study, among the trial networks that compared a newer or more intense intervention with an older or less intense intervention we saw no systematic differences between the direct and indirect comparisons (table 2). Deciding accurately which treatment was newer or more intense is often difficult. For the practical example in web appendix 1, we were initially unable to decide which of the two treatments was newer according to information provided in the review.22 By examining the full text of the primary paper,23 we found that the single direct comparison trial aimed to compare “a novel” or “newly developed” 15% gel formulation of azelaic acid and a conventional 0.75% metronidazole gel for the treatment of rosacea.

Statistically significant estimates of effects of treatment in either direct or indirect comparisons may be expected to be associated with higher prevalence of statistical inconsistency. As in the previous study,7 the indirect comparison produced fewer statistically significant results than did the direct comparison (table 3). When all three interventions in a trial network were active interventions, we selected A and B according to the estimates’ precision, which might have contributed to the observation of more statistically significant results from the direct comparisons. Given the same sample size, the direct comparison has been established to be four times more precise than the adjusted indirect comparison.1

Implications, strengths, and limitations of study

An indirect comparison had not been done in most (72/85) Cochrane reviews that provided sufficient data for both direct and indirect comparisons. The proportion of statistical inconsistency was higher in cases that did not do indirect comparisons than in those with explicit indirect comparisons (21% v 8%), although the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.45). If authors of systematic reviews did not do or report the indirect comparison because of perceived inconsistency, we may have overestimated the prevalence of statistical inconsistency in our study. However, no reason was given in reviews as to why an indirect comparison had not been done despite sufficient data being available. We anticipate that the use of indirect comparison will spread over time as more authors become aware of the available methods for indirect comparisons.

According to our knowledge, this study included the largest number of independent trial networks to investigate the inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons. Although this study included 112 trial networks in total, the number of included trials and patients within individual networks was rather small in most cases, and the available evidence was limited for exploratory subgroup analyses.

Because we may observe some disagreement between the direct and indirect estimates purely by chance, we used the proportion of statistical inconsistencies as the main outcome in this study. Wider 95% confidence intervals of inconsistencies indicated the possibility of insufficient statistical power in many cases (fig 2). Therefore, statistically non-significant inconsistency does not necessarily imply clinical consistency.

In the complete absence of direct evidence (a common scenario for using indirect comparison methods), our finding of higher than expected prevalence of significant discrepancies (14% v 5% expected) between direct and indirect evidence suggests a need for some caution in relying on indirect comparisons to make firm conclusions.

To reduce the effect of random error, all relevant evidence should be included in a systematic review. Systematic reviewers are increasingly expected to combine all possible trial evidence (both direct and indirect). Where some direct evidence exists, this is mainly to improve the precision of the estimate of the effect of treatment. Nevertheless, in our study the combined evidence improved the precision to a level reaching statistical significance in less than 4% (3/73) of such cases and cast additional doubts on 36% (14/39) of direct evidence that would have been considered conclusive (statistically significant). Therefore, the combination of inconsistent evidence may provide a misleading estimate of the effect of treatment. The statistical consistency between different evidence should be properly assessed, using the simple method used in this paper or more complex methods designed for more extensive evidence networks.24 25

Conclusions

Significant inconsistency between the direct and indirect comparisons may be more prevalent than has previously been observed. It may be more common with subjectively assessed outcomes, fewer trials included in analyses, and statistically significant results from either direct or indirect comparison. The combination of direct and indirect estimates in mixed treatment comparison should be done only after an adequate assessment of the consistency of the evidence.

What is already known on this topic

Limited empirical evidence indicated that differences between direct and adjusted indirect comparisons were only occasionally statistically significant

Indirect comparison methods have been increasingly used to evaluate competing healthcare interventions

What this study adds

Statistically significant inconsistency between direct and adjusted indirect comparisons may be more prevalent than previously observed

The risk of significant inconsistency is associated with fewer trials included in analyses, subjectively assessed outcomes, and statistically significant estimates of treatment effects by either direct or indirect comparisons

Contributors: FS had the idea for the study and is the guarantor. FS, YKL, AJS, RH, AJE, A-MG, JJD, and DGA developed the research protocol. SP-B, YKL, and FS searched for and identified relevant studies. SP-B, TX, YKL, AMG, and FS extracted and checked data from the included cases. TX and FS analysed data. AJS, AJE, RH, Y-FC, A-MG, JJD, and DGA provided methodological support and helped to interpret findings. FS drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically commented on it.

Funding: The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (G0701607). The study design, data collection, and interpretation have not been influenced by the funder.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: all authors had support from the UK Medical Research Council for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d4909

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

References

- 1.Glenny AM, Altman DG, Song F, Sakarovitch C, Deeks JJ, D’Amico R, et al. Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1-134,iii-iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards SJ, Clarke MJ, Wordsworth S, Borrill J. Indirect comparisons of treatments based on systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:841-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song F, Loke YK, Walsh T, Glenny AM, Eastwood AJ, Altman DG. Methodological problems in the use of indirect comparisons for evaluating healthcare interventions: a survey of published systematic reviews. BMJ 2009;338:b1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donegan S, Williamson P, Gamble C, Tudur-Smith C. Indirect comparisons: a review of reporting and methodological quality. PLoS One 2010;5:e11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gartlehner G, Moore CG. Direct versus indirect comparisons: a summary of the evidence. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2008;24:170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song F, Altman DG, Glenny AM, Deeks JJ. Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;326:472-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ 2005;331:897-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2004;23:3105-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lumley T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2002;21:2313-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song F, Glenny AM, Altman DG. Indirect comparison in evaluating relative efficacy illustrated by antimicrobial prophylaxis in colorectal surgery. Control Clin Trials 2000;21:488-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deeks JJ. Issues in the selection of a summary statistic for meta-analysis of clinical trials with binary outcomes. Stat Med 2002;21:1575-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckermann S, Coory M, Willan AR. Indirect comparison: relative risk fallacies and odds solution. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, Schulz KF, Juni P, Altman DG, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2008;336:601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song F, Parekh S, Hooper L, Loke YK, Ryder J, Sutton AJ, et al. Dissemination and publication of research findings: an updated review of related biases. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:iii,ix-xi,1-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 1998;352:609-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song F, Harvey I, Lilford R. Adjusted indirect comparison may be less biased than direct comparison for evaluating new pharmaceutical interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:455-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salanti G, Dias S, Welton NJ, Ades AE, Golfinopoulos V, Kyrgiou M, et al. Evaluating novel agent effects in multiple-treatments meta-regression. Stat Med 2010;29:2369-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Zuuren EJ, Graber MA, Hollis S, Chaudhry M, Gupta AK, Gover M. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;3:CD003262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elewski BE, Fleischer AB Jr, Pariser DM. A comparison of 15% azelaic acid gel and 0.75% metronidazole gel in the topical treatment of papulopustular rosacea: results of a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1444-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, Ades AE. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 2010;29:932-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu G, Ades AE. Assessing evidence inconsistency in mixed treatment comparisons. J Am Stat Assoc 2006;101:447-59. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3