Introduction

During the last decades, the advancements in micro- and nano- technology have brought tremendous encouragement to the current biomedical research. Porous silicon (pSi) has many interesting properties that are being investigated for diverse biomedical applications, including biomolecular screening, optical biosensoring, drug delivery through injectable carriers and implantable devices, and orally administered medications with improved bio-availability (1,2). There are already several FDA-approved and marketed products based on pSi technology that have found a niche in ophthalmology and another product, based on radioactive 32P-doped pSi, is currently in clinical trials, as a potential new brachytherapy treatment for inoperable liver cancer.

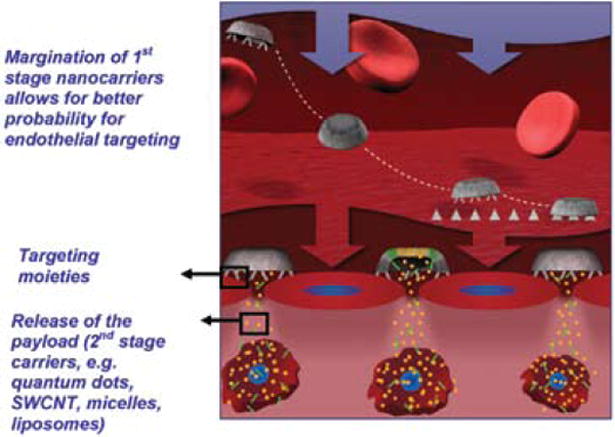

Targeted delivery could offer significant toxicity reduction in adjuvant or neo-adjuvant cancer therapies. Our research group has designed and developed a multistage nanocarrier based on the pSi technology, with the potential to overcome the multiple biological barriers encountered in the circulation and efficiently deliver therapeutics to the tumor site (3). Hemispherical disk-shaped particles with a diameter of 1–3 μm have been chosen to enhance the specific recognition and adhesion to vascular targets based on the theory of Decuzzi et al. (4) and Sakamoto et al. (5). Also, the pSi particle (first stage) has been shown to effectively load multiple types of smaller nanoparticles (second stage), such as quantum dots and single-wall carbon nanotubes, thus originating a multistage delivery system (3). The mechanism of action of the multistage system is schematically presented in Figure 1 (3).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the mechanism of action of multistage pSi nanovectors (3). The multistage delivery system is assembled by loading second-stage nanoparticles (Q-dots and SWNTs, micelles, liposomes, etc.) into the pores of mesoporous silicon microparticles. After intravenous injection, the rationally designed multistage system travels through the blood stream and, as a result of its unique size, shape, and chemical modifications, avoids RES uptake, interaction with red blood cells, and finally, migrates to the vessel wall (margination), where it adheres to the target endothelium. Multistage microparticles release their payload, which penetrates through the fenestrations of the target vasculature and eventually diffuses into the tissue surrounding the vessel. Second-stage nanoparticles are then taken up by the cells, where they accomplish their tasks.

Biocompatibility and biodegradability are the key requirements for any drug delivery carrier. Moreover, in the multistage system biodegradation plays an important role in delivering second-stage nanoparticles to the target site. In the present study we aimed at evaluating how surface modifications of the multistage pSi nanovectors affect these critical parameters.

Methods

Fabrication and Surface Modification of the Particles

pSi particles were fabricated from P++-doped wafers with a resistivity of 0.0008–0.005 Ohm-CM by electrical-chemical etching, as previously described (3). The physical dimensions and pore sizes of the particles were verified by high-resolution SEM, and the surfaces were oxidized in a piranha solution, resulting in oxidized particles. The positively charged particles were produced by the introduction of amine groups on the surface by silanization with 0.5% (vol/vol) 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) in isopropanol at room temperature. PEG-NHS with different lengths was further conjugated to the APTES-modified particles.

Biodegradation Study

Mesoporous silicon particles with different pore sizes and surface modifications were tested. The particles were incubated in PBS (pH 7.4) or fetal bovine serum (FBS) for up to 72 hr. The samples were collected at various time points and processed for ICP-AES analysis of silicic acid, which is the degradation product of pSi in the medium, and for SEM analysis of particle morphology.

Biocompatibility Evaluation

THP-1 human monocytes, J774 murine macrophages, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from ATCC and Lonza. THP-1 monocytes were differentiated into macrophages in 24-well dishes for 48–96 hr with 5–80 ng/mL of phorbol ester PMA. The cells were washed and incubated with oxidized, APTES-modified, and PEGylated particles for up to 48 hr. Zymosan particles were used as a positive control of cytokine production. The cell culture supernatant samples were collected at 1, 4, 8, 24, and 48 hr. Production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-8, in the supernatants were determined by commercial ELISA kits. Phagocytosis of the particles with various surface modifications was evaluated using J774 macrophages for 4 hr, followed by processing and SEM analysis.

Whole mouse blood, collected following a cardiac puncture, was used to evaluate the compatibility of the systems with erythrocytes. The 107–108 particles/mL of blood were incubated at 37°C, using a rotary shaker for up to 5 hr. The blood was then centrifuged, and the plasma was collected and analyzed for iron content, using ICP-AES as an indicator of hemolysis.

Results and Discussion

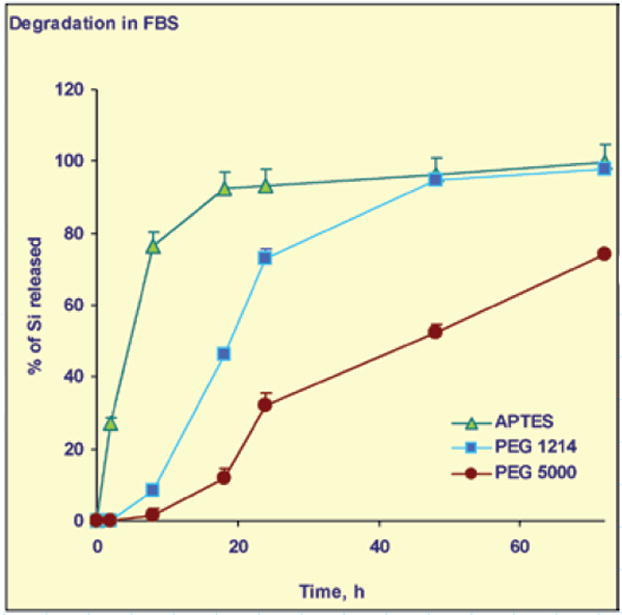

Two independent methods, ICP-AES and SEM analysis, have shown that surface modifications, as well as the porosity of the particle, affect the rate of degradation and, as a result, the amount of silicon deposited in solution in both physiological solutes (Figure 2). The degradation is complete when the concentration of silicon in the solution, as analyzed by ICP-AES, reaches a plateau. The particles conjugated to higher molecular weight PEGs and having small pore sizes exhibit degradation kinetics at a much slower rate.

Figure 2.

Degradation of pSi particles with different surface modifications over time: quantification of the particle degradation product, silicic acid, released to the degradation medium by ICP-AES.

Fine control of the degradation, which impacts the release kinetics of nanoparticles and drugs from the mesoporous silicon structures, is of fundamental importance in the development of multistage and multifunctional delivery systems. pSi microcarriers can be administered systemically and used to deliver a payload of a different nature (therapeutic, imaging, or both). The size of the pores and surface chemistry of the pSi structure can be controlled during the fabrication process and thereafter. Our data point toward the possibility to control degradation of mesoporous silicon microparticles and devices by means of particle morphology, porosity, and PEGylation and may have important clinical implications.

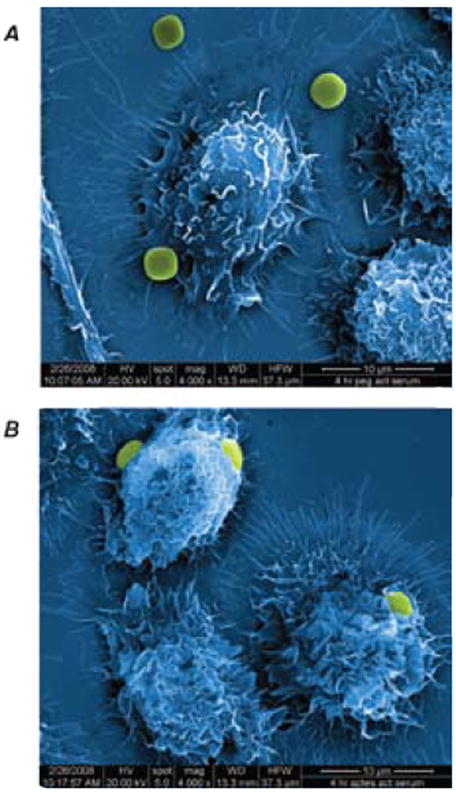

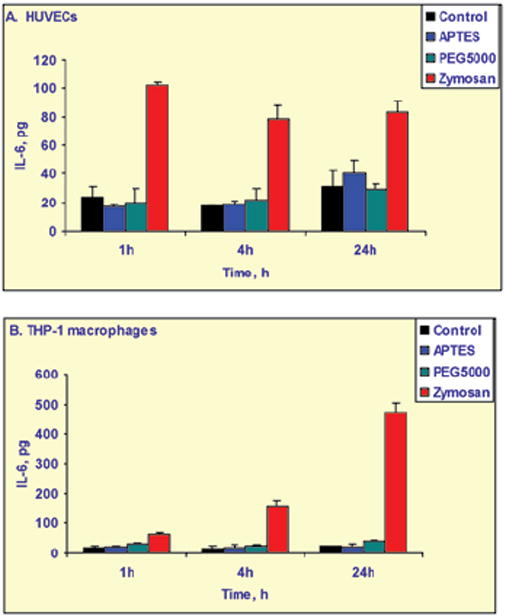

Internalization of the pSi multistage particles by murine and human immune cells can be controlled by means of particle surface modifications (Figure 3). PEGylation prevents particles from being internalized by macrophages. No significant release of proinflammatory cytokines were observed when the immune and endothelial cells were incubated with mesoporous silicon multistage carriers, as can be seen in Figure 4 for release of IL-6 from HUVEC and THP1 cells. Similar results were obtained for various other cytokines in THP-1, HL60 (differentiated human neutrophils), J774 (murine macrophages), Jurkat (T cells), and HU-VEC cells.

Figure 3.

Internalization of (A) PEGylated (PEG MW 5,000 Da) and (B) APTES pSi particles by J744 murine macrophages following 4 hr of incubation.

Figure 4.

Release of IL-6, a proinflammatory cytokine, by endothelial HUVEC cells and THP-1 human macrophages following incubation with PEGylated and non-PEGylated multistage pSi particles compared with untreated cells (control) and a positive control, zymosan particles that induce cytokine release.

The results of incubation of the carrier with whole blood show that the particles did not induce erythrocyte lysis, since plasma content of iron was not different from the untreated control.

Conclusions

The results of this study show that 1) the multistage delivery carrier is biocompatible with immune cells, endothelial cells, and erythrocytes; and 2) the degradation profile of pSi structures could be modulated as a function of morphology and surface modifications. is unique multistage system, composed of mesoporous silicon particles able to carry a payload of various nanoparticles, is currently being investigated for targeted delivery of therapeutics and imaging agents to the tumor site.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the following grants: DoDW81X-WH-04-2-0035 Project 16; NASA SA23-06-017; State of Texas, Emerging Technology Fund; DoD W31P4Q-07-1-0008; and NIH 1R01CA128797-01. The authors would like to recognize the contributions and support from the Alliance for NanoHealth (ANH).

References

- 1.Salonen J, Kaukonen AM, Hirvonen J, Lehto VP. Mesoporous silicon in drug delivery applications. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:632–653. doi: 10.1002/jps.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart MP, Buriak JM. Chemical and biological applications of porous silicon technology. Adv Mater. 2000;12:859–869. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasciotti E, Liu X, Bhavane R, Plant K, Leonard A, Price B, Cheng MC, Decuzzi P, Tour J, Robertson F, Ferrari M. Mesoporous silicon particles as a multistage delivery system for imaging and therapeutic applications. Nat Nanotech. 2008;3:151–157. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decuzzi P, Lee S, Bhushan B, Ferrari M. A theoretical model for the margination of particles within blood vessels. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:179–190. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakamoto J, Annapragada A, Decuzzi P, Ferrari M. Antibiological barrier nanovector technology for cancer applications. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2007;4:359–369. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]