Introduction

HIV infection is associated with increased risk of atherosclerosis [1, 2], but the contributing factors are not fully understood. The DAD study found that protease inhibitor (PI) therapy was associated with a 16% relative increase in the rate of myocardial infarction per year of exposure[3]. Another prospective study also reported a 14% increase in atherosclerotic disease events per year of PI use[4]. The wide heterogeneity in PI regimens in these studies raises the possibility that the class of PIs confers an increased risk of atherosclerosis. Several mechanisms such as hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance have been proposed to mediate this effect, but data from the DAD suggest that PIs increase the risk of atherosclerosis independent of effects on glucose and lipid metabolism. After adjustment for lipid levels and the presence of diabetes, PIs were still associated with an increased rate of myocardial infarction. To explain how PIs as a class could lead to increased atherosclerosis, a unifying mechanism remains to be identified.

Fibrinogen is a key component of the coagulation cascade and an acute phase reactant that is associated with coronary artery disease[5]. Fibrinogen may contribute to the development of vascular dysregulation by increasing viscosity, facilitating platelet aggregation, modulating endothelial function, and promoting smooth muscle proliferation and migration. The association between elevated fibrinogen levels and atherosclerosis may also be mediated by inflammation as fibrinogen is an acute phase reactant[6]. A large meta-analysis of 31 prospective studies of fibrinogen levels and subsequent vascular morbidity and mortality reported that a 100 mg/dL increase in fibrinogen levels was associated with a hazard ratio of 2.42 (95%CI 2.24–2.60 ) for coronary heart disease[7].

There are limited data on the relationship between PI therapy and fibrinogen levels. One study reported that subjects taking PIs had higher fibrinogen levels than PI-naïve subjects[8], whereas another study found a lack of an association between fibrinogen levels and PI treatment[9]. One study found that PI use and CRP levels were independently associated with fibrinogen levels, but found no independent association with abdominal visceral (VAT) and subcutaneous (SAT) adipose tissue[8]. None of these studies adjusted for differences in whole body regional adipose tissue[8, 9]. Increased adiposity is known to be associated with higher fibrinogen levels and regional adipose depots may change as a result of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy[10–14]. The FRAM study, in which regional adipose tissue was quantified by MRI, offers a valuable opportunity to study the association of ARV therapy, total and regional adiposity, inflammation (as assessed by C-reactive protein (CRP)), and other HIV-related factors with fibrinogen, in a nationally representative, multi-ethnic cohort of both HIV-infected participants and controls.

Design and Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional analysis of 1131 HIV infected participants and 281 controls in the study of Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change in HIV Infection (FRAM) with fibrinogen measurements. FRAM was designed to evaluate the prevalence and correlates of changes in fat distribution, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia in a representative sample of HIV-positive participants and controls in the United States. The methods have been described in detail previously [15, 16]. HIV-infected participants were recruited from 16 HIV or infectious disease clinics or cohorts between 2000 and 2002. Control participants were recruited from two centers from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. CARDIA participants were originally recruited as a sample of healthy 18- to 30-year old white and African American men and women from 4 cities in 1985-6 for a longitudinal study of cardiovascular risk factors, with population-based recruitment in 3 cities and recruitment from the membership of a prepaid health care program in the fourth city; a subgroup was recruited for FRAM at the year 15 exam in 2000-1. The protocol was approved by institutional review boards at all sites.

Plasma and Serum Measurements

Fibrinogen antigen was quantitatively measured in frozen plasma that had been stored at −70°C by immunochemistry using the BNII nephelometer (N-Antiserum to Human Fibrinogen; Dade Behring Inc., Deerfield, IL). The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variations are 2.7% and 2.6%, respectively.

hsCRP was measured in frozen plasma, using the BNII nephelometer from Dade Behring, which utilizes a particle enhanced immunonephelometric assay. The inter-assay coefficients of variation for this study range from 3.7–4.5%.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was assessed via HCV RNA levels at the UCSF clinical lab.

Other blood specimens were analyzed in a single centralized laboratory (Covance, Indianapolis, Indiana), including CD4 lymphocyte count and HIV RNA in HIV-infected participants.

Other Measurements

Age, gender, ethnicity, medical history, and risk factors for HIV were determined by self-report and alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use were assessed by standardized questionnaires[15, 16]. Height, weight, and blood pressure were measured by standardized protocols and whole body MRI was performed to quantify regional and total adipose tissue[17]. Research associates performed medical chart abstraction of medications and medical history at HIV sites[15, 16].

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were restricted to men and women with fibrinogen measurements. The 68 participants (4.6% of eligible participants) excluded because of missing fibrinogen measurements were similar in most demographic and clinical characteristics to those who had fibrinogen measurements, except they were slightly more likely to be female (47% vs. 33%, p=0.04). Analyses that compared HIV-infected persons with controls excluded HIV-infected individuals with recent opportunistic infections, as fibrinogen is an acute phase reactant, and were restricted to those between the ages of 33 and 45 (N=587 HIV+ and N=278 Controls) because the control population did not include participants outside this age range.

We first compared characteristics of HIV-infected and control subjects using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to determine the strength of the association between fibrinogen and the adipose tissue sites.

To assess the association of HIV status with fibrinogen levels, we performed multivariable linear regression using stepwise regression, with p=0.05 for entry and retention; we tested for interactions between HIV status, gender, ethnicity, and age at each step. HIV status, gender, age, and ethnicity were forced into every model. Characteristics used for multivariable adjustment included adipose tissue volume from anatomic sites measured by MRI (upper trunk, lower trunk, arm, leg and total subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and total fat)[10], level of physical activity (quartiled), current smoking status, current illicit drug use (marijuana, crack, cocaine, combination use of crack or cocaine), food consumption (self-report), regular alcohol consumption (at least weekly use), and CRP level (log 2).

In a separate multivariable linear regression analysis of HIV-infected subjects only, we assessed the independent associations of ARV use and other factors with fibrinogen levels. Gender, age, ethnicity, HIV RNA level (log 10) and CD4 count (log 2) at time of study visit were forced into every model. In addition to the factors listed above, candidates related to HIV-infection included AIDS diagnosis by CD4 or opportunistic infection, HIV duration (from date of first diagnosis of HIV infection), HCV infection (by virus detection), recent opportunistic infection status, days since last opportunistic infection, and HIV risk factors.

In multivariable models controlling for the factors above that were independent predictors, we evaluated current use of each individual ARV drug and ARV class: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), protease inhibitor (PI), and highly active ARV therapy (HAART), as previously defined[10]. Ritonavir dose, defined as high (≥400 mg given twice daily) and low (<400 mg given twice daily) versus none, was also evaluated.

Measurements of the adipose tissue from the five anatomical sites were normalized by dividing by height-squared (analogous to BMI) and summaries were back-transformed to 1.75m of height[10, 11]. Because of their skewed distribution, adipose tissue measures were log-transformed. Smoothing splines were constructed using generalized additive models in order to determine the relationship of adipose tissue with fibrinogen[18]. Examination of these smoothed curves suggested a linear relationship in some depots, but in other instances suggested non-linear relationships, which we modeled using linear splines.

Because of its skewed distribution, fibrinogen was log-transformed in all linear regression analyses; results were back-transformed to produce estimated percentage differences in fibrinogen levels. Confidence intervals were determined using the bias-corrected accelerated bootstrap method with p-values defined as one minus the highest confidence level that still excluded zero; this was necessary because the error residuals appeared to be non-Gaussian[19].

All analyses were conducted using the SAS system, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The demographics of the slightly smaller subset that had fibrinogen levels measured are shown in Table 1 and are similar to the complete FRAM cohort. As seen in the full cohort, total subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) was lower in age-restricted HIV-infected men and women compared to controls; visceral adipose tissue (VAT) was slightly lower in HIV-infected men (p=0.084) and higher in HIV-infected women (p=0.009) compared with controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-infected and Control Subjects

| Males | Females | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ | Control | P-value§ | HIV+ | Control | P-value§ | ||

| n* | 798 | 150 | 333 | 131 | |||

| Age (y) | Median (IQR) | 43.0 (38.0–49.0) | 40.0 (37.0–43.0) | <.0001 | 41.0 (35.0–47.0) | 42.0 (37.0–44.0) | 0.76 |

| Race | Caucasian | 55% | 53% | 0.034 | 33% | 50% | 0.014 |

| African American | 33% | 47% | 55% | 50% | |||

| Other | 12% | 0 | 12% | 0 | |||

| Height (cm) | Median (IQR) | 175 (171–180) | 179 (175–183) | <.0001 | 163 (158–167) | 165 (161–171) | 0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | Median (IQR) | 75 (68–83) | 85 (77–98) | <.0001 | 70 (59–82) | 75 (64–89) | 0.007 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Median (IQR) | 24 (22–27) | 27 (25–30) | <.0001 | 26 (22–31) | 28 (23–33) | 0.15 |

| VAT (L)** | Median (IQR) | 1.8 (0.8–3.0) | 2.0 (1.1–3.0) | 0.084 | 1.4 (0.6–2.4) | 1.1 (0.4–1.9) | 0.009 |

| Total SAT (L)** | Median (IQR) | 10.1 (7.1–14.2) | 14.7 (11.1–18.8) | <.0001 | 25.5 (16.4–36.2) | 30.1 (19.6–39.5) | 0.032 |

| CRP (mg/L) | Median (IQR) | 1.69 (0.75–3.91) | 0.88 (0.48–2.00) | <.0001 | 1.94 (0.81–4.70) | 1.75 (0.60–4.37) | 0.22 |

| HCVRNA+ | 20% | 3% | <.0001 | 25% | 1% | <.0001 | |

| Current CD4 (cells/uL) § | Median (IQR) | 345 (219–523) | 0.57 | 359 (196–561) | |||

| HIV RNA (1000/mL) § | Median (IQR) | 0.4 (0.4–10.8) | 0.11 | 0.5 (0.4–15.2) | |||

| Current ARV Use§: | Ritonavir | 30% | 0.15 | 26% | |||

| Indinavir | 17% | 0.073 | 13% | ||||

| Efavirenz | 27% | 0.001 | 18% | ||||

| Nevirapine | 11% | 0.007 | 18% | ||||

| Nelfinavir | 17% | 0.72 | 16% | ||||

| Kaletra | 13% | 0.85 | 13% | ||||

| Saquinavir | 10% | 0.052 | 6% | ||||

| Amprenavir | 6% | 0.11 | 4% | ||||

| Delavirdine | 1% | 0.77 | 1% | ||||

| Ritonavir by dose*** | High dose | 12% | 0.25 | 9% | |||

| Low dose | 18% | 16% | |||||

| None | 70% | 75% | |||||

n’s are for datasets that are not age-restricted and do not exclude those with a recent opportunistic infection.

height-normalized,

high dose ritonavir ≥400mg twice daily,

p-values for HIV-related factors compare HIV-infected men and women.

Fibrinogen Levels in HIV-infected Participants vs. Controls

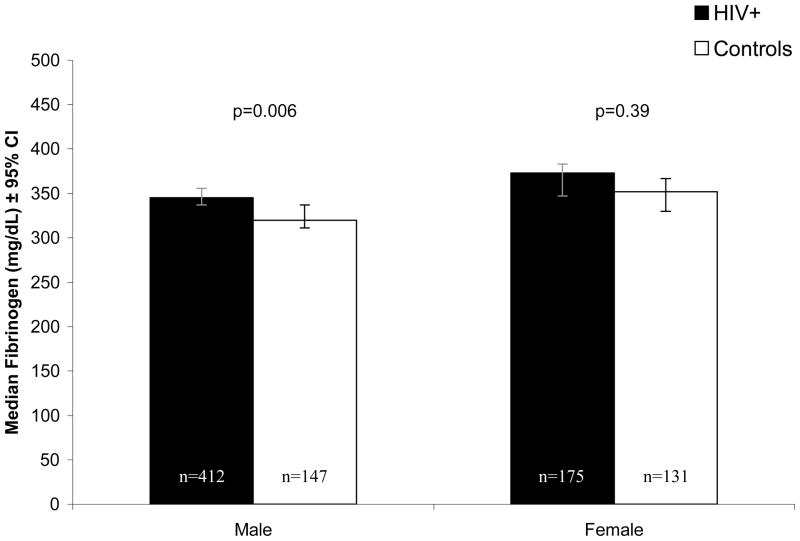

Median fibrinogen levels (mg/dL) were 8% higher in HIV-infected men (345, 95% CI: 337 to 356) compared with control men (320, 95% CI: 311 to 337, Figure 1), despite the lower levels of SAT and VAT that we found in HIV compared to control men. Similarly, median fibrinogen levels (mg/dL) were 6% higher in HIV-infected women (373, 95% CI: 347 to 383) compared to control women (352, 95% CI: 330 to 367), although this difference was not statistically significant. After multivariable adjustment for demographics, lifestyle factors, and adipose tissue, fibrinogen levels remained higher in HIV-infected compared with control men (HIV vs. Control: 12.2%, 95% CI: 6.4, 17.1, p<0.0001), while in women, being HIV-infected showed little association with fibrinogen levels (−1.1%, 95% CI: −7.2, 5.6, p=0.79).

Figure 1.

Median Fibrinogen Levels in HIV-infected and Control Subjects Open bars = control subjects. Closed bars = HIV-infected subjects. This analysis was age-restricted and excluded participants with recent opportunistic infections.

Association of PIs and NNRTIs with fibrinogen levels

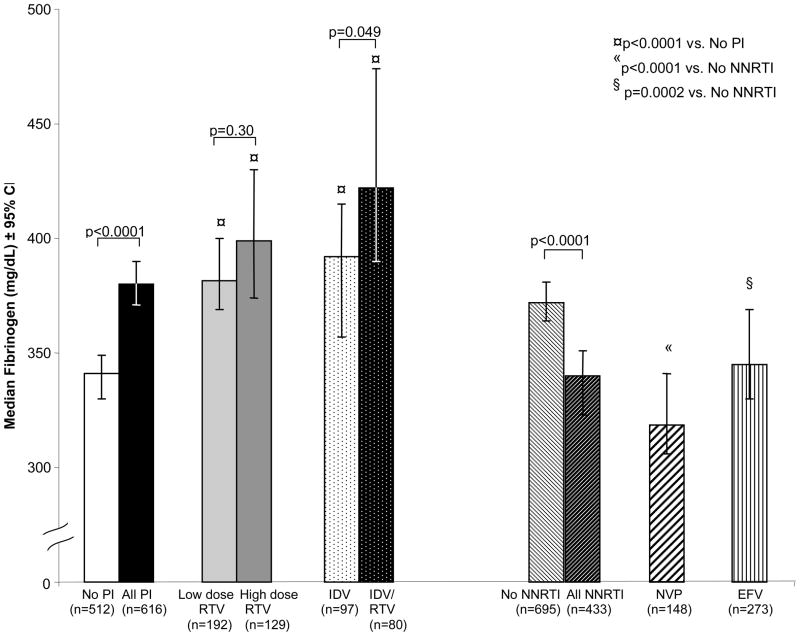

In univariate analysis, ritonavir and indinavir use was associated with higher fibrinogen levels, while efavirenz and nevirapine were associated with lower fibrinogen levels (Table 2). We also evaluated fibrinogen levels by class of ARV (Figure 2). Median fibrinogen levels (mg/dL) were 11% higher in HIV-infected subjects on any PI (380, 95% CI: 371 to 390) compared with those not on a PI (341, 95% CI: 330 to 349, p<0.0001). Compared to those not using a PI, median fibrinogen levels were 12% and 17% higher in low and high dose ritonavir users, respectively (both p<0.0001). The associations with low and high dose ritonavir remained similar in multivariable analysis.

Table 2.

Association of ARVs with Fibrinogen

| % Effect* (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrinogen (Unadjusted Model) | Ritonavir | 14.3 (10.0, 18.5) | <.0001 |

| Indinavir | 15.7 (10.7, 21.3) | <.0001 | |

| Efavirenz | −5.1 (−9.1, −0.8) | 0.020 | |

| Nevirapine | −12.8 (−17.7, −7.7) | <.0001 | |

| Fibrinogen (Adjusted Model 1)** | Ritonavir | 12.3 (7.5, 17.2) | <.0001 |

| Indinavir | 12.6 (7.1, 18.6) | <.0001 | |

| Efavirenz | −4.4 (−8.9, 0.0) | 0.049 | |

| Nevirapine | −11.6 (−16.7, −6.7) | 0.001 | |

| Fibrinogen (Adjusted Model 2)*** | Ritonavir | 11.4 (7.0, 15.6) | <.0001 |

| Indinavir | 10.2 (5.5, 15.1) | <.0001 | |

| Efavirenz | −5.9 (−9.8, −2.0) | 0.002 | |

| Nevirapine | −12.0 (−16.8, −7.2) | <.0001 | |

| CRP (log 2) | 7.2 (6.0, 8.3) | <.0001 |

Percent effect compares fibrinogen levels in ARV users to non-users for each ARV

Adjusted models also control for demographics, lifestyle factors, adipose tissue, HIV-related factors

Model 2 is further adjusted for CRP levels.

Figure 2.

Median Fibrinogen Levels in HIV-infected Subjects Using Antiretrovirals. Open bar = subjects not using PIs; solid black bar = subjects currently using any PI; solid light grey bar = subjects using lose dose ritonavir (<400 mg given twice daily); solid dark grey bar = subjects using high dose ritonavir (≥400 mg given twice daily); white bar with black dots = subjects using indinavir alone; black bar with white dots = subjects using indinavir boosted with ritonavir; white bar with diagonal black lines = subjects not using an NNRTI; black bar with diagonal white lines = subjects using any NNRTI; white bar with diagonal bolded black lines = subjects using nevirapine; white bar with vertical black lines = subjects using efavirenz.

Current indinavir users were stratified by whether they received indinavir alone or boosted with ritonavir. The indinavir groups had respectively 15% and 24% higher levels of fibrinogen compared to those not taking a PI (both p<0.0001, Figure 2). Furthermore, median fibrinogen levels were 8% higher in subjects currently taking indinavir boosted with ritonavir (422, 95% CI: 390 to 475) compared with those taking only indinavir (392, 95% CI: 357 to 415, p=0.049).

In other analyses, median fibrinogen levels were also 12% higher in patients taking lopinavir/ritonavir (382, 95% CI: 364 to 404) compared with those not on a PI (p<0.0001). Likewise, all other PIs (amprenavir, nelfinavir, and saquinavir) were also associated with higher fibrinogen levels (ranging from 7% to 14%).

Median fibrinogen levels (Figure 2) were nearly 9% lower in those HIV-infected subjects currently using of any of the NNRTIs (340, 95% CI: 323 to 351) compared with those not using an NNRTI (372, 95% CI: 364 to 381, p<0.0001). Median fibrinogen levels were significantly lower among HIV infected subjects on either the NNRTI nevirapine (318, 95% CI: 306 to 341) or efavirenz (345, 95% CI: 330 to 369) compared to those not taking an NNRTI (p<0.0001 and p=0.0002, respectively); these associations persisted after multivariable adjustment.

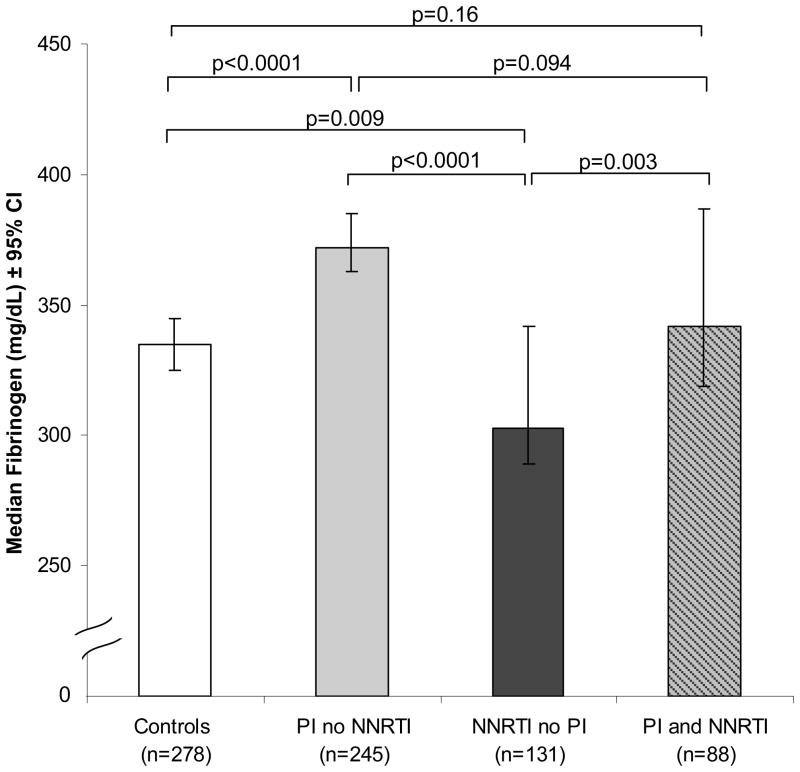

We compared median fibrinogen levels in HIV-infected subjects who were on PIs exclusive of NNRTIs, on NNRTIs exclusive of PIs, or on both a PI and NNRTI to levels in controls (Figure 3). Median fibrinogen levels (mg/dL) in HIV-infected on PIs but not NNRTIs (372, 95% CI: 363 to 385) were 11% higher than controls (335, 95% CI: 325 to 345, p<.0001). In contrast, median fibrinogen levels in HIV-infected subjects on NNRTIs but not PIs (303, 95% CI: 289 to 342) were almost 10% lower than controls (p=0.009). Furthermore, median fibrinogen levels in HIV infected subjects taking PIs and NNRTIs together (342, 95% CI: 319 to 387) were similar to controls (p=0.16). Among HIV-infected subjects, the levels of fibrinogen in both PI-using groups (PI without NNRTI; PI with NNRTI) were statistically significantly higher than those of the NNRTI without PI group (p<0.0001 and p=0.003, respectively). Moreover, the group taking PI with an NNRTI had 8% lower median fibrinogen levels than the PI without NNRTI group, but this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.094).

Figure 3.

Median Fibrinogen Levels in HIV-infected Subjects Using Antiretrovirals. Analysis restricted to subjects aged 33–45 and subjects without a recent opportunistic infection. Open bar = controls; solid grey bar = HIV-infected subjects using PI but not NNRTI; solid bar = HIV-infected subjects using NNRTI but not PI; grey bar with diagonal black lines = subjects using both PI and NNRTI.

Multivariable associations with fibrinogen

Factors independently associated with higher fibrinogen levels in HIV-infected subjects included age, African-American race, VAT, total SAT, smoking, and current HIV viral load, while current CD4 cell count and alcohol use were associated with lower fibrinogen levels (data not shown). After adjustment for these factors, we observed strong associations with specific ARV agents (Table 2) consistent with the univariate findings. Current use of the PIs indinavir and ritonavir were associated with higher fibrinogen levels (both p<0.0001). Current use of the NNRTIs nevirapine (p=0.001) and efavirenz (p=0.049) were associated with lower fibrinogen levels. The associations of these ARV drugs with fibrinogen levels persisted regardless of how adipose tissue was modeled. The magnitude of ARV associations and their statistical significance changed very little after adjustment for HDL, LDL, triglycerides, insulin resistance and blood pressure.

The relationship between CRP and fibrinogen, another marker of inflammation, was also evaluated. After multivariable adjustment, CRP was positively and strongly associated (p<0.0001) with fibrinogen in both HIV-infected subjects and controls (7.2% and 6.4% per doubling of CRP, respectively). However, the associations of the PI and NNRTI drugs with fibrinogen levels were found to be independent of CRP, as the magnitude of the PI and NNRTI associations changed little after adjusting for CRP (Table 2).

Conclusions

After adjusting for adipose tissue volume, which is known to be associated with fibrinogen levels, we found that type of ARV therapy was specifically associated with fibrinogen levels. Use of PIs as a group was associated with elevated fibrinogen levels. Subjects on PIs had 11% higher fibrinogen levels compared with those not on PIs. Koppel et al reported a similar increase when PI treated patients were compared to therapy naïve patients[8]. The PI-associated increase in fibrinogen levels was independent of adipose tissue volumes, triglyceride levels, insulin resistance, inflammation, and lifestyle factors.

Unlike previous findings of PI-induced metabolic disturbances which have been observed with some, but not all, PI drugs [20–26] elevation of fibrinogen levels here is seen with all PIs studied, suggesting a class effect. While we were not able to assess the association of more recently introduced PI drugs, we did find an association of the commonly used lopinavir/ritonavir combination and of ritonavir at boosting doses with higher fibrinogen levels. Most current PI regimens utilize ritonavir boosting.

The association between PIs and elevated fibrinogen levels may contribute to the risk of atherosclerosis. The Framingham study found that each SD increase in fibrinogen level (56 mg/dL) is associated with a 20% independent increment of risk for cardiovascular disease[27]. Although it may not be possible to directly apply the Framingham cardiovascular risk assessment to our study population, the Framingham data suggest that in our study, subjects on PIs potentially have a 14% increased risk (39 mg/dl) for cardiovascular disease compared to subjects not on PIs. A similar magnitude of disease risk for PI was reported in the DAD study[3] and by Kwong et al[4]. Thus, elevation in fibrinogen levels may be a unifying mechanism by which PIs as a class accelerate atherosclerosis.

Fibrinogen levels were also independently associated with CRP, another cardiovascular risk factor which is also associated with acute inflammation. The lack of an association of PIs and NNRTIs with CRP levels [28] and the finding that adding CRP to the multivariable analysis has virtually no effect on the association of PI with fibrinogen levels suggests that acute inflammation is not a central mechanism by which PI drugs are associated with elevated fibrinogen levels and atherosclerosis. The independent associations of PIs and CRP with fibrinogen levels, suggests that PIs may directly alter fibrinogen levels. It is possible that PIs and NNRTIs are instead more closely associated with regulation of the coagulation pathway itself. Traditional cardiovascular risk factor predictions do not take into consideration these potential effects of antiviral therapy on atherosclerosis.

In multivariable regression analysis, indinavir and ritonavir were the PIs most strongly associated with fibrinogen levels. Indinavir and ritonavir have also been shown to induce insulin resistance, and ritonavir induces hypertriglyceridemia.[21–23, 26, 27] The combination of elevated fibrinogen levels and insulin resistance or hypertriglyceridemia may confer an even higher risk of atherosclerosis than individual disorder of metabolism alone. However, PIs that do not induce these metabolic changes were also associated with higher fibrinogen levels. Prospective studies comparing individual PI therapies and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are required to assess the risk of cardiovascular disease with indinavir and ritonavir therapy compared to other PI therapy.

Ritonavir-boosting of indinavir was associated with higher fibrinogen levels than indinavir or low-dose ritonavir. The subjects on boosted indinavir regimens had the highest levels of fibrinogen in our study. Possible mechanisms include an additive effect of ritonavir itself on fibrinogen levels and/or a consequence of increasing the concentration of indinavir. The observation that high dose ritonavir was associated with higher levels of fibrinogen than lower dose ritonavir, albeit not statistically significant (p=0.30) supports the concept that total levels of PIs may be important in these effects. Further studies are necessary to assess the effects of individual PI dosage and ritonavir boosting on fibrinogen levels, as most PI regimens in common use at this time employ ritonavir boosting.

In contrast to PIs, NNRTIs were associated with lower fibrinogen levels. Subjects taking nevirapine and to a lesser extent efavirenz had lower fibrinogen levels compared to subjects not on NNRTIs. Interestingly, levels of fibrinogen with NNRTI therapy were also lower than those levels observed in healthy normal controls. The magnitude of the NNRTI effects changed very little after adjustment for lipids, including HDL levels. Koppel et al studied HIV-infected patients before the common use of NNRTI[8]. While they found no decrease in fibrinogen levels in those who switched from PI to NNRTI, the numbers switching were very small (n= 23). It is possible that by lowering fibrinogen levels, NNRTIs confer a protective effect on cardiovascular events in addition to that predicted from their increase in HDL, but further prospective studies of NNRTIs and measures of cardiovascular outcomes are required.

As PIs have been commonly taken in combination with NNRTIs in the past, we examined the relationship between PIs, NNRTIs, and fibrinogen levels. Subjects on both NNRTIs and PIs had fibrinogen levels that were intermediate between those levels in subjects on PIs alone and NNRTIs alone and comparable to fibrinogen levels in healthy controls. The combined effect of PI and NNRTI therapy on fibrinogen levels strongly suggests a direct drug effect of both therapies.

The multivariable analysis found associations of higher HIV viral load and lower CD4 cell count with higher fibrinogen levels (data not shown). Unlike PIs and NNRTIs, HIV infection is also associated with elevated CRP levels, and thus elevated CRP and fibrinogen levels may be a reflection of the underlying inflammatory state due to HIV disease. It should be noted that the effects of PI and NNRTI persist after adjusting for these factors associated with HIV itself.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. Given the cross-sectional design of the present study, we are unable to prove causality between ARV therapy and alterations in fibrinogen levels. Prospective studies are required to determine the relationship between PIs, NNRTIs, and fibrinogen levels, and relationships to CVD events. Our study cannot assess the effects of more recently introduced PI drugs. The FRAM study is ongoing, and future analysis is planned of the association of newer PI and other ARV therapies with fibrinogen levels. Additional studies are clearly needed to evaluate the relationship between markers of CVD risk in HIV infection, ARV therapy, and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

In summary, PIs as a class are associated with higher levels of fibrinogen levels, which may contribute to an increased risk of atherosclerosis in HIV-infected subjects. Ritonavir boosting may lead to higher levels of fibrinogen compared to un-boosted PIs. In contrast, NNRTIs are associated with lower fibrinogen levels. Fibrinogen levels in those subjects on NNRTIs combined with PIs are similar to those observed in healthy controls. The antiretroviral drug effects appear to be independent of inflammation. Prospective studies are needed to determine the causal relationship between ARV therapy and fibrinogen levels as well as their CVD consequences.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants RO1- DK57508, HL74814, HL 53359, and HL77499 and NIH GCRC grants M01- RR00036, RR00051, RR00052, RR00054, RR00083, RR00636, and RR00865. The funding agency had no role in the collection or analysis of the data. Carl Grunfeld had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Carl Grunfeld received research grants during the time of the study from outside affiliations with Serono Laboratories, Theratechnologies, and EMD Biosciences.

Appendix

Sites and Investigators

University Hospitals of Cleveland (Barbara Gripshover, MD); Tufts University (Abby Shevitz, MD and Christine Wanke, MD); Stanford University (Andrew Zolopa, MD and Lisa Gooze, MD); University of Alabama at Birmingham (Michael Saag, MD and Barbara Smith, PhD); John Hopkins University (Joseph Cofrancesco, MD and Adrian Dobs, MD); University of Colorado Heath Sciences Center (Constance Benson, MD and Lisa Kosmiski, MD); University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Charles van der Horst, MD); University of California at San Diego (W. Christopher Mathews, MD and Daniel Lee, MD); Washington University (William Powderly, MD and Kevin Yarasheski, MD); VA Medical Center, Atlanta (David Rimland, MD); University of California at Los Angeles (Judith Currier, MD and Matthew Leibowitz, MD); VA Medical Center, New York (Michael Simberkoff, MD and Juan Bandres, MD); VA Medical Center, Washington DC (Cynthia Gibert, MD and Fred Gordin, MD); St Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center (Donald Kotler, MD and Ellen Engelson, PhD); University of California at San Francisco (Morris Schambelan, MD and Kathleen Mulligan, MD, PhD); Indiana University (Michael Dube, MD); Kaiser Permanente, Oakland (Stephen Sidney, MD); University of Alabama at Birmingham (Cora E. Lewis, MD).

Data Coordinating Center

University of Alabama, Birmingham (O. Dale Williams, PhD, Heather McCreath, PhD, Charles Katholi, PhD, George Howard, PhD, Tekeda Ferguson, and Anthony Goudie)

Image Reading Center

St Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center: (Steven Heymsfield, MD, Jack Wang, MS and Mark Punyanitya).

Office of the Principal Investigator

University of California, San Francisco, Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the Northern California Institute for Research and Development: (Carl Grunfeld, MD, PhD; Phyllis Tien, MD; Peter Bacchetti, PhD; Dennis Osmond, PhD; Andrew Avins, MD; Michael Shlipak, MD; Rebecca Scherzer, PhD; Mae Pang, RN, MSN; Heather Southwell, MS, RD; Erin Madden, MPH; and Yong Kyoo Chang).

References

- 1.Currier JS, Taylor A, Boyd F, et al. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:506–512. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein D, Hurley LB, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Sidney S. Do protease inhibitors increase the risk for coronary heart disease in patients with HIV-1 infection? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:471–477. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200208150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friis-Moller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1723–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwong GP, Ghani AC, Rode RA, et al. Comparison of the risks of atherosclerotic events versus death from other causes associated with antiretroviral use. Aids. 2006;20:1941–1950. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247115.81832.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kannel WB. Overview of hemostatic factors involved in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Lipids. 2005;40:1215–1220. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tracy RP. Inflammation markers and coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10:435–441. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199910000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, et al. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Jama. 2005;294:1799–1809. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koppel K, Bratt G, Schulman S, Bylund H, Sandstrom E. Hypofibrinolytic state in HIV-1-infected patients treated with protease inhibitor-containing highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:441–449. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200204150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behrens G, Dejam A, Schmidt H, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance, beta cell function and lipid metabolism in HIV patients under treatment with protease inhibitors. Aids. 1999;13:F63–70. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacchetti P, Gripshover B, Grunfeld C, et al. Fat distribution in men with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:121–131. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000182230.47819.aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fat distribution in women with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:562–571. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000229996.75116.da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alessi MC, Lijnen HR, Bastelica D, Juhan-Vague I. Adipose tissue and atherothrombosis. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003;33:290–297. doi: 10.1159/000083816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bo M, Raspo S, Morra F, Cassader M, Isaia G, Poli L. Body fat is the main predictor of fibrinogen levels in healthy non-obese men. Metabolism. 2004;53:984–988. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piche ME, Lemieux S, Weisnagel SJ, Corneau L, Nadeau A, Bergeron J. Relation of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and fibrinogen to abdominal adipose tissue, blood pressure, and cholesterol and triglyceride levels in healthy postmenopausal women. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tien PC, Benson C, Zolopa AR, Sidney S, Osmond D, Grunfeld C. The study of fat redistribution and metabolic change in HIV infection (FRAM): methods, design, and sample characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:860–869. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher D, Belmonte D, Deurenberg P, et al. Organ-tissue mass measurement allows modeling of REE and metabolically active tissue mass. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E249–258. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.2.E249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hastie T, Tibshirani RJ. Generalized Additive Models. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Boostrap. London: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee GLJ, Aweeka F, Schwarz J-M, Mulligan K, Schambelan M, Grunfeld C. Single-dose lopinavir/ritonavir acutely inhibits insulin-mediated glucose disposal in healthy normal volunteers. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:658–660. doi: 10.1086/505974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee GRM, Mulligan K, Lo JC, Aweeka F, Schwarz JM, Schambelan M, Grunfeld C. Effects Of Ritonavir And Amprenavir On Insulin Sensitivity In Healthy Volunteers; Two Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Trials. AIDS. 2007 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32826fbc54. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee GA, Seneviratne T, Noor MA, et al. The metabolic effects of lopinavir/ritonavir in HIV-negative men. Aids. 2004;18:641–649. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403050-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noor MA, Lo JC, Mulligan K, et al. Metabolic effects of indinavir in healthy HIV-seronegative men. Aids. 2001;15:F11–F18. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105040-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noor MA, Parker RA, O’Mara E, et al. The effects of HIV protease inhibitors atazanavir and lopinavir/ritonavir on insulin sensitivity in HIV-seronegative healthy adults. Aids. 2004;18:2137–2144. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noor MA, Flint OP, Maa JF, Parker RA. Effects of atazanavir/ritonavir and lopinavir/ritonavir on glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity: demonstrable differences in vitro and clinically. Aids. 2006;20:1813–1821. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000244200.11006.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purnell JQ, Zambon A, Knopp RH, et al. Effect of ritonavir on lipids and post-heparin lipase activities in normal subjects. Aids. 2000;14:51–57. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Castelli WP, D’Agostino RB. Fibrinogen and risk of cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study. Jama. 1987;258:1183–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reingold JSWC, Kotler DP, Lewis CE, Tracy R, Heymsfield S, Tien PC, Bacchetti P, Scherzer R, Grunfeld C, Shlipak MG. Association of HIV Infection and HIV/HCV Coinfection with C-Reactive Protein Levels: The FRAM Study. 2007 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181685727. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]