Abstract

The type III TGF-β receptor (TβRIII or betagylcan) is a TGF-β superfamily coreceptor with emerging roles in regulating TGF-β superfamily signaling and cancer progression. Alterations in TGF-β superfamily signaling are common in colon cancer; however, the role of TβRIII has not been examined. Although TβRIII expression is frequently lost at the message and protein level in human cancers and suppresses cancer progression in these contexts, here we demonstrate that, in colon cancer, TβRIII messenger RNA expression is not significantly altered and TβRIII expression is more frequently increased at the protein level, suggesting a distinct role for TβRIII in colon cancer. Increasing TβRIII expression in colon cancer model systems enhanced ligand-mediated phosphorylation of p38 and the Smad proteins, while switching TGF-β and BMP-2 from inhibitors to stimulators of colon cancer cell proliferation, inhibiting ligand-induced p21 and p27 expression. In addition, increasing TβRIII expression increased ligand-stimulated anchorage-independent growth, a resistance to ligand- and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, cell migration and modestly increased tumorigenicity in vivo. In a reciprocal manner, silencing endogenous TβRIII expression decreased colon cancer cell migration. These data support a model whereby TβRIII mediates TGF-β superfamily ligand-induced colon cancer progression and support a context-dependent role for TβRIII in regulating cancer progression.

Introduction

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) plays a dichotomous role in human cancers, functioning both as a tumor suppressor and as a tumor promoter [1]. Many human tumors downregulate or exhibit mutations in components of the TGF-β signaling pathway, resulting in functional resistance to the homeostatic functions of the pathway [2]. Conversely, many late-stage human tumors increase TGF-β expression, which has a tumor-promoting effect by suppressing immune surveillance, inducing epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and promoting tumor invasiveness, angiogenesis, and metastasis [2]. This dual role of TGF-β as both a tumor suppressor and tumor promoter remains a fundamental roadblock to effectively targeting the TGF-β pathway for the treatment of human cancers.

TGF-β superfamily signaling is regulated and mediated by a coreceptor, the type III TGF-β receptor (TβRIII or betagylcan), which binds all three TGF-β isoforms, multiple bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), and inhibin [3–6]. TβRIII functions by presenting ligand to the respective type II and type I TGF-β superfamily receptors, which, upon ligand binding, transphosphorylate to activate the respective type I TGF-β superfamily receptor [4,7]. This leads to the phosphorylation and subsequent activation of the Smad transcription factors, which then interact with Smad4, translocate to the nucleus, and regulate the transcriptional activity of a variety of TGF-β superfamily responsive genes in a cell type-specific manner [8]. TβRIII also mediates ligand-dependent and -independent p38 pathway signaling [4,9,10], inhibits nuclear factor κB signaling [11,12], and activates Cdc42 to regulate cell proliferation and migration [13]. TβRIII inhibits TGF-β superfamily signaling through ectodomain shedding-mediated generation of soluble TβRIII (sTβRIII), which has been demonstrated to bind and sequester TGF-β away from its receptors [4,14].

In normal intestinal epithelium, TGF-β functions as a tumor suppressor through the regulation of cell growth and the induction of apoptosis [15]. TGF-β superfamily signaling is commonly disrupted in colon cancer with frequent alterations in components of the TGF-β superfamily signaling pathways [16–20]. However, studies have demonstrated that response to TGF-β is dependent on tumor stage, with TGF-β functioning to inhibit proliferation in early stages of colon cancer and promoting growth and invasion in later stages and during tumor progression [21,22]. Colon cancer cells have been demonstrated to secrete TGF-β and elevated levels of TGF-β1 are significantly correlated with metastatic disease, disease recurrence, and decreased survival [24–26]. In addition, TGF-β1 has been demonstrated to promote colon cancer cell proliferation in a Ras-dependent but Smad-independent manner [27] and to promote Ras-mediated invasiveness in intestinal epithelial cells in a TβRII-dependent manner [28]. Therefore, in late stages of colon carcinogenesis, TGF-β may function as a tumor promoter, supporting a dual role for TGF-β signaling in colon cancer progression.

Similarly to TGF-β, BMP expression is increased in colorectal tumors and correlates with poor prognosis and metastasis [29]. BMPs have diverse biologic roles in colon cancer, regulating proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis, and differentiation [30–33]. Overexpression of BMP4 in the Smad4-deficient cell line, SW480, enhances cell proliferation, migration, invasiveness, and adhesion [34]. These studies demonstrate that alterations in TGF-β and BMP signaling play a dual role in colon carcinogenesis, both inhibiting and promoting colon cancer.

TβRIII is expressed in normal intestinal goblet cells; however, it does not undergo proper posttranslational modification and is unable to bind TGF-β1, resulting in insensitivity to TGF-β1-mediated growth inhibition [35]. In contrast, neighboring absorptive cells, which express functional TβRIII, are growth-inhibited by TGF-β1, demonstrating that TβRIII can modulate TGF-β1 signaling in normal colon cells [35]. Expression of oncogenic Ras in goblet cells restores posttranslational modification of TβRIII and causes these cells to become growth-stimulated in response to TGF-β1 treatment, suggesting that K-Ras confers a more aggressive phenotype through alterations in TβRIII posttranslational modifications [35,36]. These data suggest that TβRIII may play an important role in mediating TGF-β signaling in colon cancer.

Recently, TβRIII expression has been demonstrated to be lost or decreased in multiple human cancers, including breast, prostate, ovarian, pancreatic, and non-small cell lung cancers [37–41]. TβRIII has been demonstrated to be an important regulator of cell migration, invasion, cell growth, and angiogenesis, with restoration of TβRIII expression inhibiting cancer progression [13,37]. Taken together, these data support a role for TβRIII as a mediator of TGF-β superfamily signaling during cancer progression. Here, we examined the role of TβRIII in human colon cancer.

Materials and Methods

TβRIII Gene Expression Analysis on Complementary DNA Array

An array containing normalized complementary DNA (cDNA) from colon carcinomas and matched normal tissues (n = 37) (Cancer Profiling Array; Clontech; Takara Bio Co, Madison, WI) was probed with a [32P]-labeled cDNA probe for TβRIII following methods recommended by the manufacturer. The TβRIII cDNA probe was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the forward primer 5′ GTAGTGGGTTGGCCAGATGGT 3′ and reverse primer 5′ CTGCTGTCTCCCCTGTGTG 3′. Twenty-five nanograms of purified PCR products was labeled by random primed DNA labeling using [α32P]dCTP as per the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The labeled cDNA probe was purified on a BD CHROMA SPIN+STE-100 column (BD Biosciences, Clontech; Takara Bio Co). Images were acquired using a phosphorimager, and subsequent data analysis was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The TβRIII array was normalized to a ubiquitin-probed array.

Tissue Microarray

A custom polyclonal TβRIII antibody (820) was created by immunizing rabbits with a GST-fusion protein of the human TβRIII cytoplasmic domain [37]. Immunohistochemistry for TβRIII was performed on a colon cancer tissue microarray (Cooperative Human Tissue Network, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) containing colon carcinomas (n = 323), normal colon epithelium (n = 60), and adenomatous polyps (n = 34). The array was deparaffinized, rehydrated, treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide, blocked with 10% normal goat serum, incubated with the 820 TβRIII custom polyclonal antibody at 4°C overnight, and incubated with antirabbit IgG-HRP antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were counter-stained using hematoxylin. The immunoreactivity for TβRIII was semiquantitatively scored by two independent observers in a blinded manner, with staining intensity defined as 0 to 1 (no or weak staining), 2 (moderate staining), and 3 (intense staining). All images were acquired at a magnification of x20.

Cell Culture, Stable Cell Lines, and Adenoviral Infection

Human colon cancer cell lines HT29, SW480, and SW620 were cultured in McCoy 5A + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and high-glucose Dulbecco modified Eagle medium + 10% FBS, respectively. HT29 stable cell lines, representing a pool of stable clones, were derived as previously described and maintained in 500 µg/ml G418 [37,40]. Adenoviral infections were performed as previously described [39]. All adenoviral infections were performed at a multiplicity of infection of 25 for all constructs. Cells were treated with the Ras antagonist farnesyl thiosalicylic acid (FTS) at 200 µM or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control for 3 days before harvest. Media and FTS were changed daily to maintain the correct concentration of FTS.

TGF-β Binding and Cross-linking

TGF-β binding and cross-linking experiments were performed as previously described [37,39].

Western Blot Analysis

A total of 2.5 x 105 cells were plated in six-well dishes and allowed to recover. Cells were serum-starved overnight and then treated with 100 pM TGF-β or 20 nM BMP-2 for the indicated times. The cells were lysed in boiling sample buffer and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted for the proteins of interest. Primary antibodies (p-Smad1/5/8 [no. 9511], Smad1 [no. 9743], p-Smad2 [no. 3101], Smad2 [no. 3103], pp44/ 42 [no. 9101], p44/42 [no. 9102], p-p38 [no. 4511], and p38 [no. 9212]) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and a 1:1000 dilution was used for immunoblot analysis. Primary Ras antibody (no. OP40) was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ), and a 1:2000 dilution was just for immunoblot analysis. Protein levels were determined by immunoblot analysis followed by densitometric analysis, including background subtraction and normalization to β-actin using ImageJ software (NIH).

Proliferation Assay

HT29-Neo and HT29-TβRIII cells were plated at 3000 cells per well in a 96-well plate and grown overnight with ligand stimulation (20 nM BMP-2, 40 nM BMP-2, 50 pM TGF-β, or 100 pMTGF-β). The next day, cells were pulsed with 1 µCi of 3H per well for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed in cold PBS and 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and then incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with 10% TCA. Cells were then washed with cold 10% TCA and lysed overnight with 0.2M NaOH. Lysates were then read on a scintillation counter.

Soft Agar Assay

Six-well plates were coated with a 0.8% base layer of agarose in McCoy 5A medium with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, and 500 µg/ml G418. HT29-Neo and HT29-TβRIII cells were counted and plated at 6 x 103 cells/ml in 0.4% agar in McCoy 5A medium with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, and 500 mg/ml G418. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 21 days and fed every 3 days with McCoy 5A + 10% FBS + ligand. Cells were fixed and stained with 0.005% crystal violet in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution, then washed with PBS. Colonies were counted and quantified using Bio-Rad Quantity One software (Hercules, CA).

Fibronectin Transwell Motility Assay

To assess migration, 2.5 x 105 cells were seeded in serum-free medium in the upper chamber of a transwell filter, coated both at the top and bottom with 50 µg/ml fibronectin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Cells were untreated, treated with 100 pM TGF-β or 20 nM BMP-2 and were allowed to migrate for 12 hours at 37°C through the fibronectin toward the lower chamber containing medium plus 10% FBS. Cells on the upper surface of the filter were removed, and cells that migrated to the underside of the filter were fixed and stained using the 3-Step Stain Set (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Each assay was performed in duplicate, and each experiment was conducted at least three times with three random fields from a 20x magnification analyzed for each membrane. Data analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH).

Monolayer Wound Healing Motility Assay

HT29-Neo, HT29-TβRIII, HT29-NTC, and HT29-shRNA-TβRIII cells were plated to confluence and then scratched to cause a wound. Cells were untreated, treated with 40 nM BMP-2, 100 pM TGF-β, with or without 5 µM SB431542 or 15 µM SB203580, for 24 hours. Images were taken at 0- and 24-hour time points with a Nikon inverted microscope (Melville, NY) at a magnification of x10. Cells were maintained in their selection medium at 37°C, 5% CO2 during incubation. The percentage of wound closure was calculated ± SEM.

Immunofluorescence

For actin staining, the cells were fixed in a 4% parformaldehdye and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X for 5 minutes. Blocking was performed with 1% bovine serum albumin, and cells were incubated with a 1:50 dilution of phalloidin conjugated to Texas red (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA). For E-cadherin staining, the cells were fixed with a 1:1 solution of methanol and acetone at -20°C. Blocking was performed with 1% bovine serum albumin, and cells were incubated with a 1:250 dilution of E-cadherin antibody (BD Biosciences, Madison, WI), followed by incubation with an antimouse antibody conjugated to Texas Red (Molecular Probes). Immunofluorescence images were obtained using a Nikon inverted microscope at a magnification of x60. Line scan analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH).

HT29 Xenograft Model

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University. HT29-Neo or TβRIII cells were grown in McCoy 5A + 10% FBS under the selection of G418 (500 µg/ml). Twenty-four hours before injection, cells were transferred to selection-free media. TβRIII expression was confirmed by [125I]TGF-β binding and cross-linking. A total of 1 x 106 low-passage number (P10) HT29-Neo or HT29-TβRIII cells were injected subcutaneously into the right and left flanks of BALB/cAnNCr nu/nu mice. Mice were weighed, and tumor width (W) and length (L) were measured every 3 days. Tumor volume was determined using the formula: V = 0.5 x L x W2. Mice were followed for 21 days, when some mice reached humane end points. On sacrifice, tumors were excised, weighed, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours followed by 70% ethanol. In addition, the lungs, liver, and axillary lymph nodes were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours followed by 70% ethanol to determine the sites of metastases. Tumors, lungs, livers, and lymph nodes were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to examine histology and to determine metastatic incidence.

Results

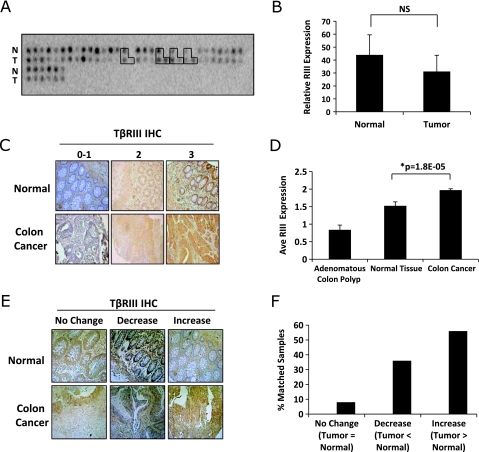

TβRIII Expression Is Increased in Human Colon Cancer

A decrease in TβRIII expression, both at the mRNA and protein levels, has been demonstrated in multiple human cancer types, including breast, kidney, non-small cell lung, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers [37–42]. As alterations in both TGF-β and BMP signaling have been demonstrated to contribute to colon carcinogenesis, we examined the expression of TβRIII in human colon cancer using a cDNA array with matched normal and colon carcinoma tissue (Figure 1A). In contrast to what has been reported in other tumor types, there was no significant difference in average TβRIII mRNA expression between normal tissue and colon carcinomas (Figure 1B). In addition, no difference in TβRIII expression was observed with regard to stage or grade of tumors (data not shown). We then examined TβRIII expression at the protein level in human colon cancer specimens by performing immunohistochemistry (IHC) for TβRIII on human tissue microarrays containing normal colon epithelium (n = 60), adenomatous polyp tissue (n = 34), and colon carcinomas (n = 323; Figure 1, C and D). When comparing TβRIII protein expression between normal colon epithelium and colon carcinomas, a modest but significant increase in TβRIII protein levels was observed (Figure 1D). Comparison between matched normal and tumor pairs (n = 25) demonstrates that whereas 8% of the matched pairs had no change and 36% had a decrease in TβRIII expression, the majority (56%) had an increase in TβRIII protein expression (Figure 1, E and F). These data demonstrate that TβRIII expression is not significantly altered at the mRNA level in human colon cancer, whereas TβRIII protein expression increases in a large subset of colon tumors, suggesting posttranscriptional regulation of TβRIII expression in human colon cancer.

Figure 1.

TβRIII expression increases during colon cancer. (A) A cDNA array with matched normal and colon tumors (n = 37) was hybridized with a [32P]-labeled probe for TβRIII. The signal intensity for each spot was determined using ImageJ software. Boxed areas represent paired normal, tumor, and metastases. (B) Graphical representation of the mean signal intensity ± SD of the intensity. NS indicates not significant. (C) TβRIII IHC was performed on a human tissue microarray of normal colon and tumor specimens. The tissue array was scored on a scale of 0 (no staining) to 3 (highest). Adenomatous colon polyp (n = 34), normal tissue (n = 60), and colon cancer (n = 323). Original magnification, x20. (D) Graphical representation of the average intensity score of TβRIII protein expression in normal and tumor tissues ± SEM. (E) TβRIII IHC was performed on a human tissue microarray of normal colon and tumor specimens. Representative matched normal and tumor sample pairs from the same patient are shown, demonstrating no change, an increase, or a decrease in TβRIII expression. Original magnification, x20. (F) Graphical representation of the percentage of matched pairs (n = 25) that demonstrate an increase (n = 14), no change (n = 2), or decrease (n = 9) in TβRIII protein expression in tumor versus normal tissue.

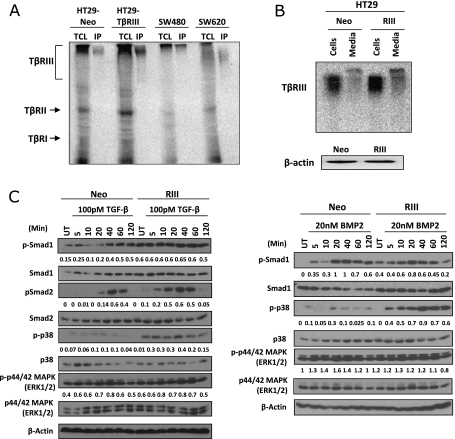

TβRIII Enhances Signaling in Colon Cancer Cells

To investigate the role of TβRIII in colon cancer, several colon cancer cell lines were analyzed for TβRIII expression. HT29, a Smad4-positive cell line derived from a primary colon carcinoma, and SW480 and SW620 cells, Smad4-deficient cell lines that are derived from the primary colon cancer (SW480) and metastatic lymph node (SW620) from the same patient, all express TβRIII, albeit with different patterns of posttranslational modification (Figure 2A). To examine the effects of an increase in TβRIII expression on colon cancer, HT29 colon cancer cell lines stably expressing Neo or TβRIII were created, and TβRIII expression was verified by binding and cross-linking 125I-TGF-β (Figure 2, A and B). The expression of both membrane-bound TβRIII and sTβRIII was increased in HT29-TβRIII cells relative to HT29-Neo cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

TβRIII is expressed in colon cancer cell lines and enhances BMP-2- and TGF-β-mediated signaling. (A) Binding and cross-linking of total cell lysates (TCL) (left lanes) and immunoprecipitation (IP) for TβRIII (right lanes) from four different cell lines: HT29 stable cell lines, namely, HT29-Neo and HT29-TβRIII; SW480 cells, derived from a primary colorectal adenocarcinoma; and SW620 cells, derived from the metastatic lymph node site of a colorectal adenocarcinoma from the same patient as the SW480 line. (B) Expression of sTβRIII in HT29 stable cell lines. Cells were grown in 10% FBS McCoy 5A for 24 hours. TβRIII and sTβRIII expression was examined in cells and medium by binding and cross-linking. β-Actin serves as a total protein control (bottom panel). (C) HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were serum-starved overnight and then treated with 100 pM TGF-β or 20 nM BMP-2 during the indicated time course (minutes). Western blot analyses were performed for the indicated proteins. Densitometric analysis is shown normalized to β-actin.

Restoring TβRIII expression has been demonstrated to inhibit TGF-β responsiveness in other cancer types, including in breast cancer, as well as inhibiting BMP responsiveness in pancreatic cancer [37,43]. To determine whether increased expression of TβRIII alters TGF-β or BMP-2 responsiveness, phosphorylation of Smad2, Smad1/5/8, p38, and ERK in response to ligand stimulation was examined in HT29-Neo and HT29-TβRIII Smad4-expressing colon cancer cells. There was a significant increase in basal levels of p-Smad1/5/8 in HT29-TβRIII cells in the absence of exogenous ligand treatment (Figure 2C). In response to TGF-β1, p-Smad2, p-Smad1/5/8, and p-p38 levels were increased in HT29-TβRIII cells relative to HT29-Neo cells, with an earlier onset of Smad2 phosphorylation (Figure 2C). In response to BMP-2, HT29-TβRIII cells exhibited an earlier onset of Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation and increased p-p38 signaling (Figure 2C). No change in ERK signaling was observed, basally or with ligand treatment. These data suggest that TβRIII has both ligand-independent and ligand-dependent effects on signaling because Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation was enhanced both basally and in response to exogenous ligand treatment, and Smad2 and p38 enhancement was ligand specific. Together, these data demonstrate that TβRIII increases TGF-β- and BMP-2-mediated canonical and noncanonical signaling in colon cancer cells, in stark contrast to the inhibitory effects of TβRIII on TGF-β superfamily signaling in other cancer contexts [37,39].

TβRIII Increases Ligand-Stimulated Proliferation in Colon Cancer Cells by Decreasing Basal and Ligand-Stimulated p21 and p27 Expression

TGF-β treatment in the presence of oncogenic K-Ras, which regulates posttranslational modification of TβRIII, has been demonstrated to induce proliferation and downregulate p21 in colon cancer cells [27,36]. To examine the effects of TβRIII expression on proliferation, HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were treated with BMP-2 or TGF-β and proliferation was examined by 3H-thymidine incorporation. In the absence of ligand stimulation, no significant difference was observed in proliferation between HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells (Figure 3, A and B). However, TGF-β1 or BMP-2 treatment resulted in moderate growth arrest in HT29-Neo cells (10%–15% reduction in growth with TGF-β1 treatment and 7%–15% reduction with BMP-2 treatment) (Figure 3, A and B). In contrast, treatment of HT29-TβRIII cells with either BMP-2 or TGF-β resulted in resistance to ligand-induced growth arrest and a modest, but significant increase in cell growth (≥5% increase in growth with both TGF-β1 and BMP treatment; Figure 3, A and B). Although there is a modest increase in proliferation in the HT29-TβRIII ligand-treated cells, these differences are significant (Student's t test, P < .05) in comparison to the reduction in proliferation observed in the HT29-Neo ligand-treated cells. These data demonstrate that TβRIII can inhibit ligand-mediated growth arrest and stimulate proliferation in response to TGF-β or BMP-2 in colon cancer cells. Similar results were obtained in the SW480 cells in response to BMP treatment (Figure W1C).

Figure 3.

TβRIII expression increases colon cancer in vitro tumorigenicity. (A) HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were treated with 20 or 40 nM BMP-2 for 24 hours. Proliferation was analyzed by a 3H incorporation assay. The percent proliferation was determined by normalizing the counts to those of untreated samples. (B) HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were treated with 50 or 100 pM TGF-β1 for 24 hours. Proliferation was analyzed by a 3H incorporation assay. (C) HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were treated with 2 or 10 nM BMP-2 and 50 or 100 pM TGF-β1 for 24 hours. HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were treated with 200 µM FTS or DMSO for 3 days. Western blot analyses were performed to analyze protein levels of p21, p27, p15, cyclin D, and Ras with β-actin as a total protein control. (D) HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were plated in a soft agar assay untreated or treated with 20 nM BMP-2, 40 nM BMP-2, 50 pM TGF-β, or 100 pM TGF-β for 21 days. The mean percent colony formation ± SEM is shown normalized to the untreated Neo or TβRIII. Average colony number is shown above the bar graph. (E) HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were treated with 40 nM BMP-2 or 100 pM TGF-β for 48 hours and examined for apoptosis by Western blot analysis of caspase 9 levels. Densitometric analysis is shown normalized to β-actin. (F) HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were treated with 50 µM 5-fluorouracil for 48 hours. Cells were concurrently treated with 20 nM BMP-2 or 100 pM TGF-β and examined for apoptosis induction by Western blot analysis of PARP cleavage. Densitometric analysis is shown normalized to β-actin.

TGF-β and BMP regulate proliferation through induction of a number of cell cycle proteins, including the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21 [44]. To explore the mechanism by which TβRIII regulates colon cancer cell proliferation, the effect of TβRIII on p21, p27, cyclin D, and p15 levels was examined. In response to treatment with either BMP-2 or TGF-β1, p21 and p27 protein levels increased with no change in cyclin D1 or p15 levels in HT29-Neo cells (Figure 3C). SW480-GFP cells exhibit a modest increase in levels of p27 in response to TGF-β treatment and a modest decrease in p21 levels in response to BMP-2 ligand stimulation (Figure W1B). In contrast, HT29-TβRIII cells exhibit a reduction in basal p21 levels relative to HT29-Neo cells and neither BMP-2 nor TGF-β induced p21 or p27 expression (Figure 3C). Similarly, SW480-TβRIII cells exhibited a reduction in basal p21 levels relative to SW480-GFP cells, and TGF-β treatment failed to stimulate p27 expression (Figure W1B). Interestingly, no significant alterations in p21 mRNA levels were observed in the HT29-Neo or HT29-TβRIII cell lines in response to TGF-β or BMP-2 treatment (Figure W1A), suggesting that TβRIII promotes proliferation in colon cancer cells through the down-regulation of p21 at the protein level.

As oncogenic K-Ras, which regulates posttranslational modification of TβRIII, has been demonstrated to induce proliferation and downregulate p21 in colon cancer cells, we examined the contribution of Ras signaling to TβRIII-mediated decreases in p21 levels by using the Ras inhibitor, FTS [27,36,45]. As previously observed, treatment with FTS inhibits Ras and significantly upregulates p21 protein levels in HT29-Neo and HT29-TβRIII cells (Figure 3C) [45]. Inhibition of Ras by FTS treatment also attenuates TβRIII-mediated inhibition of ligand-induced p21 levels, suggesting that TβRIII-mediated regulation of p21 occurs at least partially in a Ras-dependent manner in colon cancer cells (Figure 3C).

TβRIII Increases Colon Cancer Cell Tumorigenicity In Vitro

To examine the effect of TβRIII on anchorage-independent colon cancer cell growth, a soft agar assay was performed with HT29-Neo and HT29-TβRIII cells. In the absence of ligand stimulation, no difference in colony formation was observed between HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells (Figure 3D). In response to either BMP-2 or TGF-β treatment, HT29-Neo cells had a modest but significant decrease in colony formation. In contrast, in HT29-TβRIII cells colony formation significantly increased in response to ligand stimulation (Figure 3D). These data demonstrate that TβRIII expression enhances ligand-stimulated anchorage-independent growth, a hallmark of tumorigenicity, in colon cancer cells.

TGF-β signaling has been demonstrated to regulate apoptosis, with resistance to apoptosis being another characteristic of tumorigenicity. Although increasing TβRIII expression only modestly decreased anoikis in HT29 cells (data not shown), increasing TβRIII expression significantly reduced ligand-induced apoptosis, as demonstrated by decreased levels of caspase 9 in HT29 cells (Figure 3E). In addition, the expression of TβRIII inhibited chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil)-induced apoptosis in HT29 cells (Figure 3F). These data demonstrate that TβRIII can inhibit ligand-induced and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis and may inhibit anoikis. This resistance to apoptosis supports a protumorigenic role for TβRIII in colon cancer.

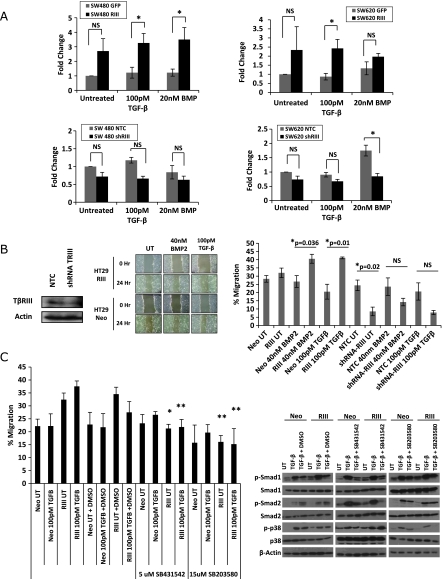

TβRIII Increases Colon Cancer Cell Motility

TβRIII has been demonstrated to regulate cell motility and invasion in both epithelial and cancer cells [13,37,38]. In the context of other cancers, the ability to inhibit cell motility and invasion plays an important role in TβRIII's function as a suppressor of cancer progression. The increased tumorigenicity observed in colon cancer cells with increased TβRIII expression in vitro suggests that TβRIII may regulate motility in colon cancer cells as well. A fibronectin transwell migration assay demonstrated a trend toward an increase in basal migration of SW480-TβRIII and SW620-TβRIII cells in the absence of ligand stimulation, whereas TGF-β- and BMP-2– treated SW480-TβRIII and SW620-TβRIII cells had a significant increase in motility in comparison to GFP-infected control cells (Figures 4A and W3). However, no further increase in migration is observed between untreated and ligand-stimulated TβRIII cells, suggesting that TβRIII mediates an increase in basal migration. In addition, HT29-TβRIII cells consistently migrated faster than the HT29-Neo cells in response to ligand treatment in a monolayer wound healing assay (Figure 4B). In a reciprocal manner, short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated silencing of endogenous TβRIII significantly decreased both basal and ligand-induced migration in HT29 cells (Figure 4B). In addition, knockdown of TβRIII in SW480 and SW620 cells demonstrated a trend toward a decrease in migration in a fibronectin transwell migration assay, with a significant reduction in migration on BMP ligand stimulation in SW620 cells (Figures 4A and W3).

Figure 4.

TβRIII increases colon cancer cell migration. (A) SW480 and SW620 GFP, TβRIII, NTC, or shTβRIII adenovirally infected cells were plated in a fibronectin transwell migration assay. Cells were plated in serum-free conditions on a fibronectin-coated transwell (50 µg/ml) with and without ligand treatment. Migration toward serum was measured by counting the number of cells on the filter after 12 hours. Fold change ± SEM is demonstrated. * P < .05. NS indicates not significant. (B) HT29-Neo, TβRIII, and NTC (nontargeting control) or shRNA TβRIII adenovirally infected cells were plated in a monolayer scratch wound assay. Cells were grown to confluence and then wounded by scratching and treated with 40 nM BMP-2 or 100 pM TGF-β. The percent migration was calculated by measuring the wound closure over time (0 and 24 hours). (C) Scratch wound assay with HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells treated with ligand and the ALK5 inhibitor SB431542 (5 µM) or the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (15 µM). The percent migration was calculated by measuring the wound closure over time (0 and 24 hours). *P = .02 RIII UT versus RIII UT+SB431542. **P=.01 RIII 100 pMTGF-β versus RIII 100 pM TGF-β + SB431542, RIII UT versus RIII UT + SB203580, RIII 100 pM TGF-β versus RIII 100 pM TGF-β + SB203580. Western blot analysis showing inhibition of TGF-β signaling with inhibitor treatment. Cells were treated with 100 pM TGF-β for 40 minutes, with or without DMSO, 5 µM SB431542 or 15 µM SB203580 treatment.

As TβRIII expression in colon cancer cells enhanced both Smad and p38 signaling (Figure 2), we examined the contribution of these pathways to TβRIII-mediated stimulation of migration. HT29-Neo or TβRIII cells were treated with the ALK5 inhibitor SB431542 or the p38 inhibitor SB203580, and effects on migration were assessed in a monolayer wound healing assay. The ALK5 inhibitor and the p38 inhibitor both inhibited TβRIII-mediated stimulation of migration (Figure 4C). On treatment with either the ALK5 inhibitor SB431542 or the p38 inhibitor SB203580, HT29-TβRII cells migrated at a rate comparable to HT29-Neo cells and did not demonstrate a ligand-induced increase in migration. This suggests that TβRIII regulates migration in colon cancer cells through both the canonical (ALK5) and noncanonical (p38) TGF-β signaling pathways.

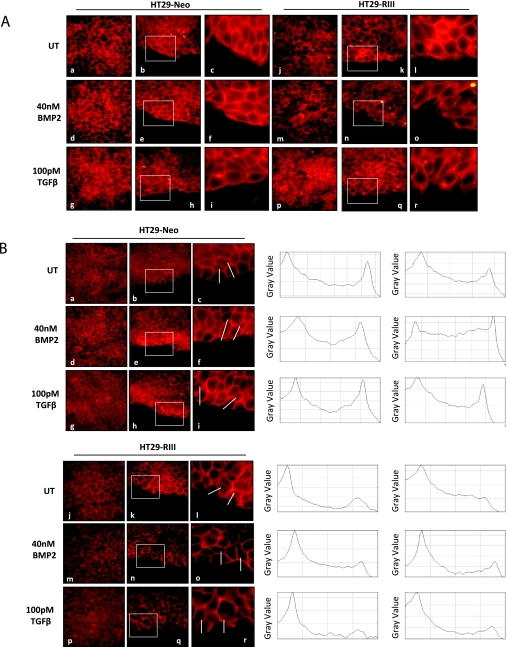

Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton occurs during most types of cell migration. TGF-β has been demonstrated to induce activation of the actin cytoskeleton [46,47]. Loss of cell-cell junctions can also occur during cell migration, which can be followed by the loss or decreased expression of the cell junction protein E-cadherin [47]. Consistent with an increased migratory phenotype, HT29-TβRIII cells exhibit alterations in actin and E-cadherin staining relative to HT29-Neo cells (Figure 5, A and B). Although HT29-Neo cells demonstrated organized actin and E-cadherin staining with cuboidal cell morphology, sharply defined cell-cell contacts and a smooth edge along the wound and in confluent areas of the culture (Figure 5, A and B), HT29-TβRIII cells exhibited a more elongated cell phenotype, with disorganized actin and E-cadherin staining, more diffuse localization and a decrease in staining at cell-cell junctions (Figure 5, A and B). In addition, HT29-TβRIII cells formed lamellipodia with membrane ruffling along the scratch edge, which was not observed in the HT29-Neo cells. Whereas HT29-Neo cells demonstrated E-cadherin staining along the edge of the wound, HT29-TβRIII cells lacked E-cadherin staining in cells lining the edge of the wound, as demonstrated by line scan analysis of E-cadherin intensity across individual cells (Figure 5B). Collectively, these data support a TβRIII-mediated increase in colon cancer cell migration, which stands in contrast to the effect of TβRIII in other cancer cell lines where TβRIII expression significantly inhibits both motility and invasiveness [13,37,38].

Figure 5.

TβRIII alters actin and E-cadherin localization in colon cancer cells. (A) Actin (phalloidin) immunofluorescent staining. HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were grown to confluence and then wounded by scratching and treated with 40 nM BMP-2 or 100 pM TGF-β. At 18 hours after scratch, cells were fixed and stained for actin. Images show actin staining in confluent culture (a, d, g, j, m, p) and along the wound edge (b, e, h, k, n, q). Original magnification, x60. Boxed area (b, e, h, k, n, q) is shown enlarged in c, f, i, l, o, r. (B) E-cadherin immunofluorescent staining. HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were grown to confluence and then wounded by scratching and treated with 40 nM BMP-2 or 100 pM TGF-β. At 18 hours after scratch, cells were fixed and stained for E-cadherin. Images show E-cadherin staining in confluent culture (a, d, g, j, m, p) and along the wound edge (b, e, h, k, n, q). Original magnification, x60. Boxed area (b, e, h, k, n, q) is shown enlarged in c, f, i, l, o, r. Line scan analysis of individual cells (ImageJ software; NIH) shows E-cadherin staining intensity in a single cell from the interior toward the wound edge. The line demonstrates the area of measured intensity.

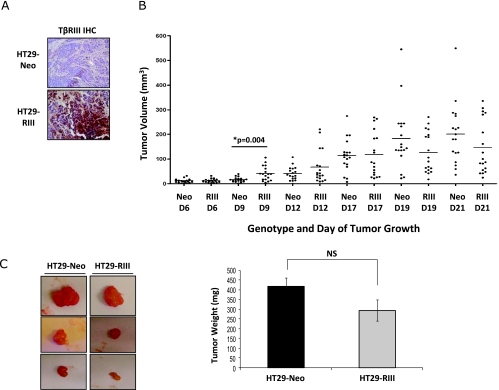

Figure 6.

TβRIII enhances early colon cancer tumorigenicity in vivo. A total of 1 x 106 HT29-Neo or HT29-TβRIII colon cancer cells were injected subcutaneously into the right and left flanks of BALB/cAnNCr nu/nu mice. Mice were weighed, and tumor width (W) and length (L) were measured every 3 days. Tumor volume was determined using the formula: V = 0.5 x L x W2. (A) TβRIII IHC of HT29-Neo and TβRIII tumors at day 21. (B) Graphical representation of HT29-Neo and TβRIII tumor volume over time (D indicates day). D9, *P = .004. (C) Representative images of HT29-Neo and TβRIII xenograft tumors and graphical comparison of final tumor mass ± SEM of HT29-Neo and TβRIII xenografts at day 21. NS indicates not significant.

TβRIII Enhances Early Colon Cancer Tumorigenicity In Vivo

The expression of TβRIII in colon cancer cells increased tumorigenicity in vitro, with increased proliferation and cell migration and a reduction in apoptosis in response to ligand. To investigate the in vivo effects of TβRIII on tumorigenicity, we performed xenograft studies with the HT29 stable cell lines. HT29-Neo and HT29-TβRIII cells were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of female Balb/c Nu/Nu mice, and tumor volume was measured every 3 days. Early in the study, HT29-TβRIII tumors were significantly larger than the HT29-Neo tumors (day 9; Figure 6B). However, by day 21, no significant difference in tumor volume or tumor mass was observed between HT29-Neo and TβRIII tumors (Figure 6, B and C), and no metastases were observed in either HT29-Neo or HT29-TβRIII xenograft mice. TβRIII expression was examined by IHC (day 21 tumors), and all HT29-TβRIII tumors maintained TβRIII overexpression in comparison to HT29-Neo tumors (Figure 6A). These results suggest that TβRIII enhances early tumorigenicity in vivo but that other factors may compensate to ameliorate these effects during cancer progression in this model system.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that, in contrast to cancers of the breast, kidney, lung, ovary, pancreas, and prostate where TβRIII expression is decreased, in human colon cancer, TβRIII expression is not significantly altered at the mRNA level and is increased at the protein level. In colon cancer cells, increasing TβRIII expression enhanced both TGF-β- and BMP-2-induced signaling, including phosphorylation of p38, Smads 1/5/8, and Smad2. Further, TβRIII induced resistance to ligand-mediated growth arrest, increased proliferation through a decrease in p21 induction and increased in vitro tumorigenicity in response to either BMP or TGF-β treatment as well as in vivo tumorigenicity at early time points. The increase in tumorigenicity is due to a TβRIII-mediated resistance to ligand- and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, increased anchorage-independent cell growth, and increased cell migration. Collectively, these data suggest a role for TβRIII as a mediator of TGF-β superfamily function during colon cancer progression.

The maintenance and increase in TβRIII expression observed in colon cancer in comparison to normal colon tissue is in striking contrast to what has been previously observed in multiple human cancer types, including breast, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers [37–41], where TβRIII expression is lost early in cancer progression and significantly inhibits metastasis, motility, invasion, and angiogenesis through sTβRIII-mediated down-regulation of TGF-β signaling [37,38,48,49]. In colon cancer, there is no significant change in TβRIII expression at the mRNA level, whereas TβRIII protein expression is significantly increased in 56% of matched normal and tumor pairs (Figure 1E), suggesting posttranscriptional regulation of TβRIII expression. Indeed, oncogenic K-Ras-dependent posttranscriptional regulation of TβRIII has been reported in colon cancer, resulting in a more tumorigenic phenotype [36]. As K-Ras is mutated in up to 50% of colon cancer patients, and these patients have a worse prognosis [50], the current results suggest that TβRIII could function downstream of oncogenic K-Ras to mediate this effect. Further supporting this hypothesis is the attenuation of TβRIII-mediated inhibition of ligand-induced p21 up-regulation in the presence of the Ras inhibitor, FTS (Figure 3C). The interaction of TβRIII and the Ras pathway remains to be further explored.

How might sustained or increased TβRIII expression promote colon cancer progression? We demonstrate here that increasing TβRIII expression in colon cancer cells enhances both canonical and noncanonical TGF-β superfamily signaling in colon cancer cells, with an increase in the basal phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 and both BMP-2 and TGF-β ligand-enhanced phosphorylation of Smad2, Smad1/5/8, and p38 (Figure 2). These results are consistent with the well-established ligand presentation role of TβRIII, where TβRIII binds TGF-β superfamily ligands and increases ligand binding to respective type I and type II TGF-β superfamily receptors to enhance signaling [6,51]. The enhancement of p38 signaling, as well as the ability of TβRIII to regulate the biology of Smad4 deficient colon cancer lines, both suggest that TβRIII has both Smad4-dependent and -independent effects on signaling and biology in colon cancer cells. As increased levels of TGF-β have been demonstrated to correlate with increased proliferation and invasion of colon cancer cells in vitro, disease progression, and a poorer prognosis for human colon cancer patients [24,26–28], the ability for TβRIII to enhance TGF-β superfamily signaling provides one potential mechanism for TβRIII promoting colon cancer progression. These results are also consistent with the observation that markers of BMP (i.e., ID1) and TGF-β signaling (i.e., PAI-1) are increased in colon cancer tissue relative to matched normal tissue (Figure W2). In contrast, TβRIII has been previously demonstrated to downregulate Smad signaling in other tumor types, in part through sTβRIII-mediated sequestration of ligand [37]. Interestingly, in colon cancer, whereas TβRIII is shed to produce sTβRIII (Figure 2B), and increasing TβRIII expression does increase the level of sTβRIII (Figure 2B), the level of sTβRIII relative to TβRIII is relatively low compared with other cancer cell lines, including breast cancer lines (data not shown) [37]. Thus, TβRIII may exert a different role in colon cancer than in other solid tumors owing to the maintenance of expression during colon cancer progression and the relative preservation of cell surface TβRIII relative to sTβRIII in colon cancer.

Increased TβRIII-mediated TGF-β superfamily signaling seems to promote colon cancer progression by altering numerous aspects of colon cancer biology. Increased TβRIII expression enhances proliferation in response to treatment with either BMP-2 or TGF-β, largely through TβRIII-mediated down-regulation of both basal and ligand-induced p21 and p27 levels in HT29 cells and a decrease in basal p21 levels and a lack of ligand-mediated increase in p27 levels in SW480-TβRIII cells (Figures 3C and W1B). This alteration in p21 levels may occur through Smad4-mediated mechanisms or through the TβRIII-mediated regulation of the noncanonical p38 pathway. Treatment with the Ras inhibitor FTS attenuated this TβRIII-mediated repression of ligand-induced p21, suggesting that this occurs, at least partially, in a Ras-dependent manner (Figure 3C). Oncogenic K-Ras has also been demonstrated to induce proliferation in response to TGF-β, associated with down-regulation of p21 and PTEN [36], in part through posttranscriptional regulation of TβRIII, further supporting a role for TβRIII downstream of oncogenic K-Ras in colon cancer. Expression of TβRIII in colon cancer cells also confers an increase in anchorage independent growth. Although this may be due in part to increased proliferation, we also noted TβRIII-mediated resistance to ligand-induced apoptosis, which may contribute to the enhanced colony formation (Figure 3).

The effects of TβRIII on promoting resistance to apoptosis in colon cancer contrasts with the reported role for TβRIII in prostate and renal cell cancer, where expression of TβRIII or treatment with sTβRIII has been demonstrated to enhance apoptosis in vivo [9,42,52]. Similar to the differences noted above, some of these alterations could be due to the relative effect of sTβRIII versus full-length TβRIII. However, at least in the context of renal cell cancer, the effects of TβRIII on enhancing apoptosis were due to the cytoplasmic domain and mediated through p38 phosphorylation [42]. Although the precise mechanism by which TβRIII regulates apoptosis remains to be defined, the divergent effects of TβRIII on apoptosis in different contexts further highlights the context-dependent nature of TβRIII in regulating cancer biology.

The context-dependent effects of TβRIII are perhaps most striking when examining the effects of TβRIII on migration. We have previously demonstrated that restoring TβRIII expression in breast, ovarian, lung, pancreatic, and prostate cancer cells inhibits ligand-induced migration [37–41,53], with robust effects on decreasing directional persistence through activation of Cdc42 and increasing filopodia formation [13]. Here we report that, in the context of colon cancer, increasing TβRIII expression may enhance basal and significantly enhances ligand-induced migration, whereas shRNA-mediated silencing of endogenous TβRIII expression inhibits both basal and ligand-mediated cell migration, suggesting a role for TβRIII in both ligand-dependent and -independent migration in colon cancer cells (Figures 4 and W3). We further demonstrate that TβRIII-mediated increases in colon cancer cell migration are dependent on TβRIII-mediated enhancement of ALK-5 and/or p38 signaling, suggesting both Smad4- dependent and -independent effects (Figure 4C). Consistent with an effect of increasing cell migration, increasing TβRIII expression in colon cancer cells reorganized the actin cytoskeleton from predominantly cell-cell junction localization to a more diffuse localization, increased lamellipodia formation along a scratch wound edge, and decreased E-cadherin staining at cell-cell junctions (Figure 5). Whereas TβRIII seems to regulate cell migration through effects on the actin cytoskeleton in multiple cellular contexts, this seems to be mediated through different pathways. Indeed, the ability of TβRIII to either increase or decrease Smad-dependent signaling, to contribute to non-Smad signaling, and to regulate signaling through the production of sTβRIII provides multiple mechanisms by which TβRIII could differentially regulate cell migration in different contexts [4]. Current investigations are focused on elucidating the mechanistic basis for the context-dependent effects of TβRIII on migration.

On the basis of the robust effects of TβRIII on enhancing ligand-stimulated colony formation in soft agar (Figure 3D) and migration (Figure 4), we were surprised to note only a modest, yet significant, enhancement of colon cancer xenograft growth by TβRIII at early time points (Figure 6), with no significant differences observed at later time points. This enhancement is consistent with our in vitro observations in colon cancer models and remains in stark contrast to the robust inhibition of xenograft growth by TβRIII in lung and prostate cancer models [38,41] and of breast cancer metastasis in a syngeneic model [37]. The modest effect on colon cancer here may be due to alterations in ligand-mediated effects occurring during in vivo tumorigenesis, a lack of significant ligand stimulation in the xenograft model, the use of a nonorthotopic xenograft model, or our inability to monitor the effect on metastasis in the model system used. As the HT29 cell line has been demonstrated to have a low engraftment rate with limited metastasis when implanted orthotopically [54], an orthotopic study may be limited in its ability to provide additional data on the effects of TβRIII on colon cancer metastasis. Indeed, we have recently defined important contributions of the host immune system in defining the effects of TβRIII on cancer progression in vivo (B. Hanks and G.C. Blobe, unpublished observations). Future studies will further explore the context-dependent effects of TβRIII on cancer progression in orthotopic, syngeneic murine models.

In conclusion, in contrast to other tumor types, TβRIII expression is maintained and enhanced in human colon cancers and functions to promote colon cancer progression through promotion of proliferation, migration, anchorage-independent growth, and resistance to apoptosis. Taken together, these data suggest that similar to the role of TGF-β superfamily signaling pathways, the role of TβRIII in regulating/mediating cancer biology is cell type and context dependent. As such, targeting this axis will require a more detailed understanding of the role TβRIII and the entire TGF-β superfamily signaling pathway in human cancer biology.

Supplemental Methods

p21 Reverse Transcription-PCR

A total of 3 x 105 HT29-Neo and TβRIII cells were plated in a six-well plate and allowed to recover. Cells were then treated with 10 nM BMP-2, 40 nM BMP-2, 100 pM TGF-β, or 400 pM TGF-β for 24 hours. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit per the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Half a microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for reverse transcription-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Each PCR contained 1 µg of cDNA along with p21 primers: hp21, forward 5′ CAGGGGACAGCAGAGGAAGA 3′ and reverse 5′ TTAGGGCTTCCTCTTGGAGAA 3′; or hGAPDH, forward 5′ GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT 3′ and reverse 5′ TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG 3′ primers.

Western Blot Analyses

A total of 2.5 x 105 SW480 cells were plated in six-well plate and allowed to recover, then adenovirally infected with GFP or FL-TβRIII-GFP as described previously. At 36 hours after infection, cells were treated with BMP-2 (2 and 10 nM) or TGF-β1 (50 or 100 pM) for 24 hours. Western blot analyses were performed to analyze protein levels of p21 (no. 2946; Cell Signaling Technology) and p27 (no. 2552; Cell Signaling Technology) protein level with β-actin as a total protein control. Densitometric analysis, including background subtraction and normalization to β-actin, was performed using ImageJ software (NIH).

Proliferation Assay

SW480 cells adenovirally infected with GFP or FL-TβRIII-GFP as described previously and were plated at 3 x 103 cells per well in a 96-well plate and grown overnight with ligand stimulation (20 nM BMP-2, 40 nM BMP-2, 50 pM TGF-β, or 100 pMTGF-β). The next day, cells were pulsed with 1 µCi of 3H per well for 4 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed in cold PBS and 10% TCA and then incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with 10% TCA. Cells were then washed with cold 10% TCA and lysed overnight with 0.2 NaOH. Lysates were then read on a scintillation counter.

ID1 and PAI-1 Expression Analysis

Matched normal colon mucosa and colon adenocarcinoma gene expression data (Affymetrix U133 Plus 2) from 32 patients were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) GSE8671. Raw expression data (.CEL) files were MAS5 normalized using Affymetrix Expression Console Version 1.0. MAS5 data were then log2 transformed using the log transform function in MATLAB (release R2009a). To examine the differences in expression level between normal and tumor tissue, the Affymetrix U133 Plus 2 probe set annotation file (release 24) was acquired from the Affymetrix Web site, and probe sets were identified for each gene of interest. When multiple probes were present for a given gene, probe expression levels were averaged for each sample. A paired t test (GraphPad Prism 4.0; Graph Pad, Inc, La Jolla, CA) was used to calculate differences in gene expression between matched normal mucosa and colon adenocarcinoma samples.

Abbreviations

- TβRIII

type III TGF-β receptor

- sTβRIII

soluble TβRIII

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (RO1-CA135006 and RO1-CA136786 to G.C.B. and F32-CA1361252 to C.E.G).

This article refers to supplementary materials, which are designated by Figures W1 to W3 and are available online at www.neoplasia.com.

References

- 1.Massague J. TGFβ in cancer. Cell. 2008;34:215–230. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pardali K, Moustakas A. Actions of TGF-β as tumor suppressor and pro-metastatic factor in human cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:21–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esparza-Lopez J, Montiel JL, Vilchis-Landeros MM, Okadome T, Miyazono K, Lopez-Casillas F. Ligand binding and functional properties of betaglycan, a co-receptor of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily. Specialized binding regions for transforming growth factor-β and inhibin A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14588–14596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatza CE, Oh SY, Blobe GC. Roles for the type III TGF-β receptor in human cancer. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirkbride KC, Townsend TA, Bruinsma MW, Barnett JV, Blobe GC. Bone morphogenetic proteins signal through the transforming growth factor-β type III receptor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7628–7637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez-Casillas F, Wrana JL, Massague J. Betaglycan presents ligand to the TGF β signaling receptor. Cell. 1993;73:1435–1444. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernabeu C, Lopez-Novoa JM, Quintanilla M. The emerging role of TGF-β superfamily coreceptors in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:954–973. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massague J. TGF-β signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margulis V, Maity T, Zhang XY, Cooper SJ, Copland JA, Wood CG. Type III transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptor mediates apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma independent of the canonical TGF-β signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5722–5730. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.You HJ, Bruinsma MW, How T, Ostrander JH, Blobe GC. The type III TGF-β receptor signals through both Smad3 and the p38 MAP kinase pathways to contribute to inhibition of cell proliferation. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2491–2500. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Criswell TL, Arteaga CL. Modulation of NFκB activity and E-cadherin by the type III transforming growth factor β receptor regulates cell growth and motility. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32491–32500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.You HJ, How T, Blobe GC. The type III transforming growth factor-β receptor negatively regulates nuclear factor κB signaling through its interaction with β-arrestin2. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1281–1287. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mythreye K, Blobe GC. The type III TGF-β receptor regulates epithelial and cancer cell migration through β-arrestin2-mediated activation of Cdc42. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8221–8226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vilchis-Landeros MM, Montiel JL, Mendoza V, Mendoza-Hernandez G, Lopez-Casillas F. Recombinant soluble betaglycan is a potent and isoform selective transforming growth factor-β neutralizing agent. Biochem J. 2001;355:215–222. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Pasche B. TGF-β signaling alterations and susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:R14–R20. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl486. Spec No 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady WM, Myeroff LL, Swinler SE, Rajput A, Thiagalingam S, Lutterbaugh JD, Neumann A, Brattain MG, Chang J, Kim SJ, et al. Mutational inactivation of transforming growth factor β receptor type II in microsatellite stable colon cancers. Cancer Res. 1999;59:320–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howe JR, Bair JL, Sayed MG, Anderson ME, Mitros FA, Petersen GM, Velculescu VE, Traverso G, Vogelstein B. Germline mutations of the gene encoding bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A in juvenile polyposis. Nat Genet. 2001;28:184–187. doi: 10.1038/88919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kodach LL, Wiercinska E, de Miranda NF, Bleuming SA, Musler AR, Peppelenbosch MP, Dekker E, van den Brink GR, van Noesel CJ, Morreau H, et al. The bone morphogenetic protein pathway is inactivated in the majority of sporadic colorectal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1332–1341. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neibergs HL, Hein DW, Spratt JS. Genetic profiling of colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2002;80:204–213. doi: 10.1002/jso.10131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie W, Rimm DL, Lin Y, Shih WJ, Reiss M. Loss of Smad signaling in human colorectal cancer is associated with advanced disease and poor prognosis. Cancer J. 2003;9:302–312. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200307000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engle SJ, Hoying JB, Boivin GP, Ormsby I, Gartside PS, Doetschman T. Transforming growth factor β1 suppresses nonmetastatic colon cancer at an early stage of tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3379–3386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu S, Huang F, Hafez M, Winawer S, Friedman E. Colon carcinoma cells switch their response to transforming growth factor β1 with tumor progression. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:267–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warusavitarne J, McDougall F, de Silva K, Barnetson R, Messina M, Robinson BG, Schnitzler M. Restoring TGFβ function in microsatellite unstable (MSI-H) colorectal cancer reduces tumourigenicity but increases metastasis formation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0606-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman E, Gold LI, Klimstra D, Zeng ZS, Winawer S, Cohen A. High levels of transforming growth factor β 1 correlate with disease progression in human colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:549–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregoire M, Garrigue L, Blottiere HM, Denis MG, Meflah K. Possible involvement of TGFβ1 in the distinct tumorigenic properties of two rat colon carcinoma clones. Invasion Metastasis. 1992;12:185–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robson H, Anderson E, James RD, Schofield PF. Transforming growth factor β1 expression in human colorectal tumours: an independent prognostic marker in a subgroup of poor prognosis patients. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:753–758. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan Z, Kim GY, Deng X, Friedman E. Transforming growth factor β1 induces proliferation in colon carcinoma cells by Ras-dependent, smad-independent down-regulation of p21cip1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9870–9879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujimoto K, Sheng H, Shao J, Beauchamp RD. Transforming growth factor-β1 promotes invasiveness after cellular transformation with activated Ras in intestinal epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2001;266:239–249. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motoyama K, Tanaka F, Kosaka Y, Mimori K, Uetake H, Inoue H, Sugihara K, Mori M. Clinical significance of BMP7 in human colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1530–1537. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9746-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck SE, Jung BH, Fiorino A, Gomez J, Rosario ED, Cabrera BL, Huang SC, Chow JY, Carethers JM. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling and growth suppression in colon cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G135–G145. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00482.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng H, Makizumi R, Ravikumar TS, Dong H, Yang W, Yang WL. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 is overexpressed in colonic adenocarcinomas and promotes migration and invasion of HCT116 cells. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1033–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardwick JC, Van Den Brink GR, Bleuming SA, Ballester I, Van Den Brande JM, Keller JJ, Offerhaus GJ, Van Deventer SJ, Peppelenbosch MP. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 is expressed by, and acts upon, mature epithelial cells in the colon. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:111–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishanian TG, Kim JS, Foxworth A, Waldman T. Suppression of tumorigenesis and activation of Wnt signaling by bone morphogenetic protein 4 in human cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:667–675. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.7.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng H, Ravikumar TS, Yang WL. Overexpression of bone morphogenetic protein 4 enhances the invasiveness of Smad4-deficient human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;281:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng X, Bellis S, Yan Z, Friedman E. Differential responsiveness to autocrine and exogenous transforming growth factor, (TGF) β1 in cells with nonfunctional TGF-β receptor type III. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan Z, Deng X, Friedman E. Oncogenic Ki-ras confers a more aggressive colon cancer phenotype through modification of transforming growth factor-β receptor III. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1555–1563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong M, How T, Kirkbride KC, Gordon KJ, Lee JD, Hempel N, Kelly P, Moeller BJ, Marks JR, Blobe GC. The type III TGF-β receptor suppresses breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:206–217. doi: 10.1172/JCI29293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finger EC, Turley RS, Dong M, How T, Fields TA, Blobe GC. TβRIII suppresses non-small cell lung cancer invasiveness and tumorigenicity. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:528–535. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon KJ, Dong M, Chislock EM, Fields TA, Blobe GC. Loss of type III transforming growth factor β receptor expression increases motility and invasiveness associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition during pancreatic cancer progression. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:252–262. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hempel N, How T, Dong M, Murphy SK, Fields TA, Blobe GC. Loss of betaglycan expression in ovarian cancer: role in motility and invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5231–5238. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turley RS, Finger EC, Hempel N, How T, Fields TA, Blobe GC. The type III transforming growth factor-β receptor as a novel tumor suppressor gene in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1090–1098. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Copland JA, Luxon BA, Ajani L, Maity T, Campagnaro E, Guo H, LeGrand SN, Tamboli P, Wood CG. Genomic profiling identifies alterations in TGFβ signaling through loss of TGFβ receptor expression in human renal cell carcinogenesis and progression. Oncogene. 2003;22:8053–8062. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon KJ, Kirkbride KC, How T, Blobe GC. Bone morphogenetic proteins induce pancreatic cancer cell invasiveness through a Smad1-dependent mechanism that involves matrix metalloproteinase-2. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:238–248. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jakowlew SB. Transforming growth factor-β in cancer and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:435–457. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halaschek-Wiener J, Wacheck V, Schlagbauer-Wadl H, Wolff K, Kloog Y, Jansen B. A novel Ras antagonist regulates both oncogenic Ras and the tumor suppressor p53 in colon cancer cells. Mol Med. 2000;6:693–704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edlund S, Landstrom M, Heldin CH, Aspenstrom P. Transforming growth factor-β-induced mobilization of actin cytoskeleton requires signaling by small GTPases Cdc42 and RhoA. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:902–914. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-08-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamazaki D, Kurisu S, Takenawa T. Regulation of cancer cell motility through actin reorganization. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bandyopadhyay A, Lopez-Casillas F, Malik SN, Montiel JL, Mendoza V, Yang J, Sun LZ. Antitumor activity of a recombinant soluble betaglycan in human breast cancer xenograft. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4690–4695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bandyopadhyay A, Zhu Y, Malik SN, Kreisberg J, Brattain MG, Sprague EA, Luo J, Lopez-Casillas F, Sun LZ. Extracellular domain of TGFβ type III receptor inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:3541–3551. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benhattar J, Losi L, Chaubert P, Givel JC, Costa J. Prognostic significance of K-ras mutations in colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1044–1048. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90272-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez-Casillas F, Payne HM, Andres JL, Massague J. Betaglycan can act as a dual modulator of TGF-β access to signaling receptors: mapping of ligand binding and GAG attachment sites. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:557–568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bandyopadhyay A, Wang L, Lopez-Casillas F, Mendoza V, Yeh IT, Sun L. Systemic administration of a soluble betaglycan suppresses tumor growth, angiogenesis, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in a human xenograft model of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2005;63:81–90. doi: 10.1002/pros.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee JD, Hempel N, Lee NY, Blobe GC. The type III TGF-β receptor suppresses breast cancer progression through GIPC-mediated inhibition of TGF-β signaling. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:175–183. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flatmark K, Maelandsmo GM, Martinsen M, Rasmussen H, Fodstad O. Twelve colorectal cancer cell lines exhibit highly variable growth and metastatic capacities in an orthotopic model in nude mice. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1593–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.