Abstract

Using a sample of individuals (277 males, 315 females) studied since birth in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development, the present study investigated how early pubertal maturation and school transition alter youth trajectories of social competence during the transition to adolescence. Social competence showed strong continuity, with the most socially competent children remaining so in adolescence. Early pubertal maturation and school transitions accentuate individual differences, increasing social competence among more competent youth, but further diminishing social competence among less competent individuals. In essence, facing challenges that require social competence may further separate competent individuals from less competent peers. Thus, the psychosocially rich become richer, while the psychosocially poor become poorer.

Social competence, by definition, is a dynamic construct, requiring increasingly complex skills as youth age. It remains unclear, however, how social competence is affected by the rapid intraindividual and contextual changes that occur during the transition to adolescence. Research suggests that there is generally strong continuity of social competence during earlier developmental periods (from early childhood to middle childhood; Obradovic et al., 2006), but studies of the continuity of social competence from childhood to adolescence have yielded inconsistent findings (cf. Masten et al., 1995; Obradovic et al., 2006).

In the present study, we focus on two experiences that may impact the continuity of social competence during the transition to adolescence: early pubertal maturation and moving from elementary to middle school. Early pubertal development is associated with both positive (e.g., greater popularity, more leadership positions, and higher peer status; Simmons & Blyth, 1987) and negative (hostile peer interactions, internalizing problems, externalizing behavior, and social withdrawal; Ge, Brody, Conger, Simons, & Murray, 2002) psychosocial consequences. Similarly, the transition from elementary school to middle or junior high school is also linked with both positive (e.g., increased social competence; Proctor & Choi, 1994) and negative (e.g., poor social adjustment, disrupting peer groups, diminished social competence; Berndt, Hawkins, & Jiao, 1999) outcomes. One explanation for these varied findings, consistent with the notion that developmental transitions accentuate individual differences, may be that the impact of early pubertal maturation and school transition on social competence varies as a function of individuals’ level of competence prior to adolescence. Specifically, early pubertal maturation and school transitions may increase competence among more competent individuals but undermine it among less competent individuals.

To the extent that socially competence is a general indicator of resilience, we expect that those youth with the greatest social competence will face challenges and stressors with positive adaptation. We hypothesize that individuals with the highest social competence before the adolescent transition will be positively affected by early pubertal maturation and by changing schools, whereas individuals with lower social competence prior to adolescence will be at risk for declines in social competence. That is, we predict that individual differences will be accentuated during the transition to adolescence (Caspi & Moffitt, 1993), with those who were more competent in childhood becoming increasingly so and those who were relatively less competent evincing further declines in social functioning.

Method

Participants

The present analyses use data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD). Families were recruited during the first 11 months of 1991, from hospitals located in or near Charlottesville, VA; Irvine, CA; Lawrence, KS; Little Rock, AR; Madison, WI; Morganton, NC; Philadelphia, PA; Pittsburgh, PA; Seattle, WA; and Boston, MA. Screening and enrollment were accomplished in three stages: a hospital screening at birth, a phone call 2 weeks later, and an interview when the infant was 1 month old (see NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005 for details). A total of 1,364 individuals were enrolled in the study. On average, mothers had 14.4 years of education and the family income was 3.6 times the poverty level. Twenty-four percent of the sample reported minority heritage, 11% of the mothers had not completed high school, and 14% of the families were headed by a single mother.

Data analyses were limited to 592 youth (277 males, 315 females) who were examined by a nurse for pubertal development at least once and attended public school (school transition information was only available for youth in public school settings). Data were drawn from 54 months to age 15 from mother, child, and nurse reports. The analytic sample and full sample did not differ in family income, parent education, birth order, or ethnicity, or social competence at any age; there is a higher proportion of girls in the analytic sample than in the full sample.

Measures

Social Competence

There are two approaches to the methodological challenge of studying the same construct across developmental periods. First, researchers can examine the construct by utilizing the same measure across multiple time points (homotypic continuity), but this approach is limited in that it is unclear how well a single measure adequately operationalizes the construct of interest in each developmental phase. A second option is to examine the construct by creating measures of developmentally appropriate markers of the construct at each developmental stage (heterotypic continuity). This approach is limited because it is impossible to discern if observed variations in stability are due to actual differences in a construct or merely variation in measurement. Previous work with conflicting accounts of the continuity of social competence across the transition to adolescence have used multifaceted measures of social competence, reflecting developmentally specific measures of competence (Masten et al., 1995; Obradovic et al., 2006). In the present study, we create an age-invariant measure of social competence from early childhood to adolescence, which we validate with age-specific measures for each period.

Constructing an age-invariant measure of social competence

An age-invariant measure of social competence was created from 8 items from the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliot, 1991). Mothers (or primary caregivers) reported how often a statement reflecting ability in social interactions was true of their child (e.g., “Makes friends easily”, with ‘Never’, ‘Sometimes’, and ‘Often’ as response options), providing three assessments of social competence in early childhood (54 months, kindergarten, and 1st grade), 4 assessments in middle childhood (3rd, 4th, and 5th grades), and 2 assessments in adolescence (6th grade and age 15).

Age-specific measures of social competence

At each developmental period (early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence) age-specific markers of social competence derived from the literature on social competence were identified.

In early childhood, the interaction style of children with their peers was used as a marker of social competence. At 54 months, Kindergarten, and 1st grade, mothers named up to six regular playmates and report on how a child plays with his or her peers (19 items; derived from Quality of Classroom Friends; Clark & Ladd, 2000; e.g., “Play happily together,” “Often show a pattern where one child dominates over other child”; 4-point scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). Two variables are derived: positive peer interactions (reciprocal, balanced play) and negative peer interactions (conflictual, hostile play).

In middle childhood, developmentally appropriate measures of social competence were peer aggression (reversed), prosocial behavior with peers, and friendship quality. In 3rd, 4th, and 5th grades, mothers responded to 43 statements(Child Behavior with Peers; Ladd & Profilet, 1996; responses from 1 [Not true] to 3 [Often true]) that assessed peer aggression (e.g., “My child loses his/her temper easily with peers”; α’s=.89–.90) and prosocial behavior with peers (“My child is cooperative with peers”; α’s=..87–.91. Lastly, in 3rd, 4th, and 5th grades, children self-assessed perceptions of a “best” friend (‘X’; Friendship Quality Questionnaire; Parker & Asher, 1993). Children respond on a 5-point scale ((“Not at all true” to “Really true”; e.g., “When mad, I talk to <X> about it”). on a 5-point scale). Friendship quality is calculated as the mean of responses, with higher scores indicating higher quality friendship (α’s=.87–.90).

Finally, during adolescence, 5 measures were used as indices of socially competent behavior: friendship quality, intimate exchange with peers, prosocial behavior with peers, overt aggression (reversed), and popularity. Friendship quality (Parker & Asher, 1993) was assessed the same in the 6th grade and 15-year follow-up (see previous paragraph; Friendship quality (α’s=.92–.93) and intimate exchange with peers (e.g., “ <X> and I tell each other private things”; α’s=.80–.87) were calculated. Slightly different measures were used to assess aggression and prosocial behavior with peers during adolescence in the 6th grade and 15-year follow-up. During the 6th grade, peer aggression (α=.90), prosocial behavior with peers (α=.91), and overt aggression (α=.91) were assessed by the Child Behavior with Peers measure (see previous paragraph). At age 15, overt aggression was measured with the Aggression Scale (Little et al., 2003); individuals rate the validity of 18 statements (e.g., “I often threaten others to get what I want” from “Not at all true” to “Completely true”; 6 items; α=.82). At age 15, popularity with peers is assessed by 8 self-report items (e.g., “How many people in your grade think that you are not popular?” on a 7-point scale from “Almost nobody” to “Almost everybody”; α=.76; Cillessen & Rose, 2005).

Reliability and validity of the age-invariant measure of social competence

The reliability of the age-invariant measure of social competence was adequate at each time point (at 54 months, α=.67; Kindergarten α=.68; Grade 1 α=.70; Grade 3 α=.75; Grade 4 α=.73; Grade 5 α=72; Grade 6 α=74; 15 years α=.71). The age-invariant measure of social competence was positively correlated with all measures of positive peer interactions in each developmental period (early childhood: rs=.25 to .31, all ps < .01; middle childhood: rs=.11 to .49, all ps<.01; adolescence: rs=.18 to .42, all ps < .01) and negatively correlated with negative peer interactions (early childhood, rs=−07 to −.20; 1 nonsignficant, 2 ps<.01; middle childhood rs=−.29 to−.30, all ps<.01; adolescence r=−.14, p<.01). At age 15, adolescent self-reported social competence was positively correlated with the age-invariant measure of social competence (r=.29, p < .01).

Timing of pubertal development

Nursing professionals assessed individuals’ pubertal development using Tanner staging (male: genital development and pubic hair; females: breast development and pubic hair) in grades 4, 5 6 and at age 15. Mean pubertal development was calculated at each time point separately for males and females. Individuals who were one standard deviation above their sex group mean at a time point were identified as “early-maturers.”

Transition to middle school

Transitioning to a new school was operationalized as moving from a school where an individual was enrolled in the oldest grade taught and transitioning to a new school where an individual was enrolled in the lowest grade taught. Because of our focus on school transitions around adolescence, school transitions prior to grade 4 were not evaluated.1

Plan of Analyses

We used two distinct analytic techniques: person-centered analyses (semi-parametric group based modeling) and variable-centered analyses (growth-curve modeling). To the extent that social competence varies at the individual level, it is useful to utilize both approaches to understand contributors to differences in average levels of social competence as well as contributors to differences in individual patterns of social competence over time. In the person-centered analyses, we examine if early maturation or school transitions impact youth differentially as a function of their trajectory of social competence. In the variable-centered analyses, we test for an interaction between relative pre-adolescent social competence (compared to other individuals in the sample) and either early puberty or school transition. Males and females are examined separately. Data were assumed to be missing at random, and all available data was used in the models.

Results

Person-Centered Analyses

Semi-parametric group based modeling was used to identify patterns of social competence over time (Nagin, 2005). Individuals are grouped based on their pattern of social competence across all time points (e.g., there are no random effects within trajectory). Model selection was based on 3 criteria: (1) the lowest BIC value relative to other models tested, (2) a conceptually clear result, and (3) a solution in which each group included more than 5% of the sample. Posterior probabilities of group membership assign individuals to their most likely trajectory group accordingly. After identifying the best solution, early pubertal timing and school transition were entered as time-varying covariates, testing how the impact early pubertal timing and school transition varied by group trajectory.

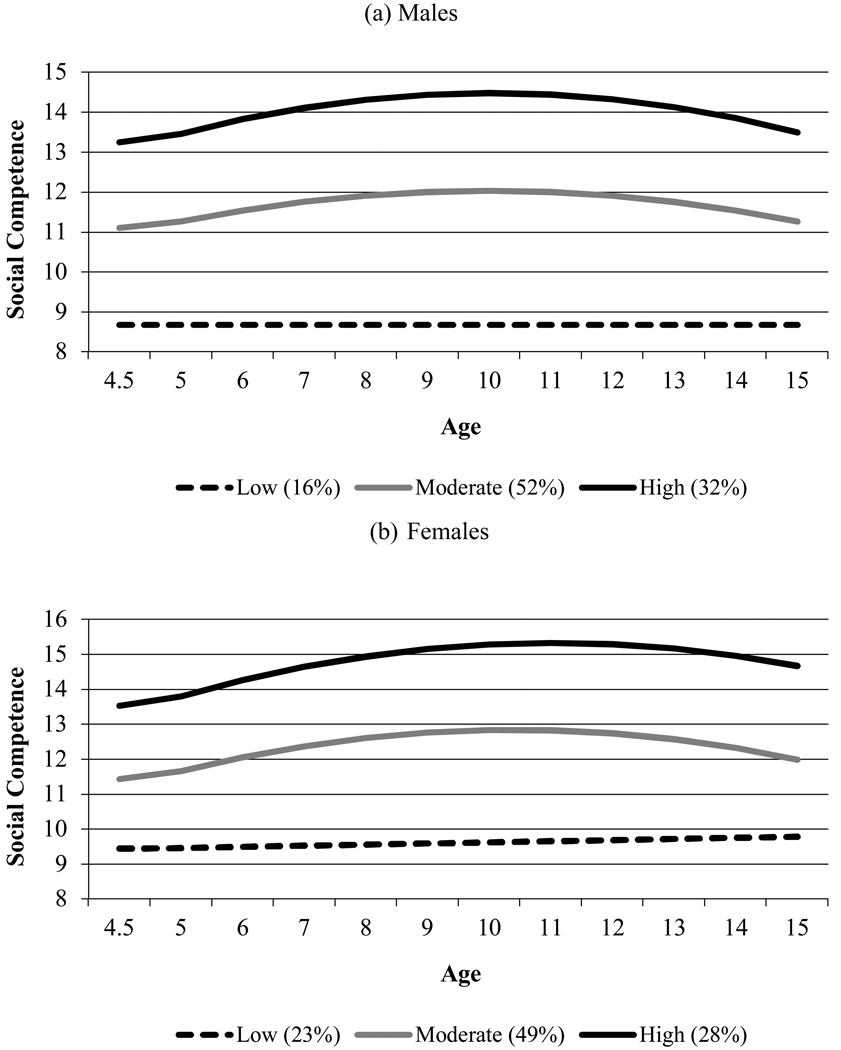

Although the four-group solution yielded the lowest BIC value (for males, 3-group solution BIC=−4398.42, 4-group solution BIC=−4350.68; for females, 3-group solution BIC=−5102.06, 4-group solution BIC= −5059.60.), a 3-group solution was selected for both males and females as providing the best fit to the data because the 4-group solution did not (a) identify a trajectory unique in shape beyond the 3-group solution and (b) one group in the 4-group solution consisted of fewer than 5% of the sample among both males and females.2 Posterior probabilities indicated that individuals were excellently matched to trajectory group (posterior probabilities ≥ .90 among both males and females) and patterns of social competence were similar among both sexes. Three patterns of social competence were found: high, moderate, and low trajectory groups (Figure 1). Among both sexes, the high and moderate trajectory groups showed quadratic patterns of growth, with social competence increasing throughout middle childhood, peaking around grade 5, and declining thereafter. The low trajectory group was generally low and stable in social competence across time (although among females there was a slight linear increase).

Figure 1.

Group-based Trajectories of Social Competence Among Males and Females

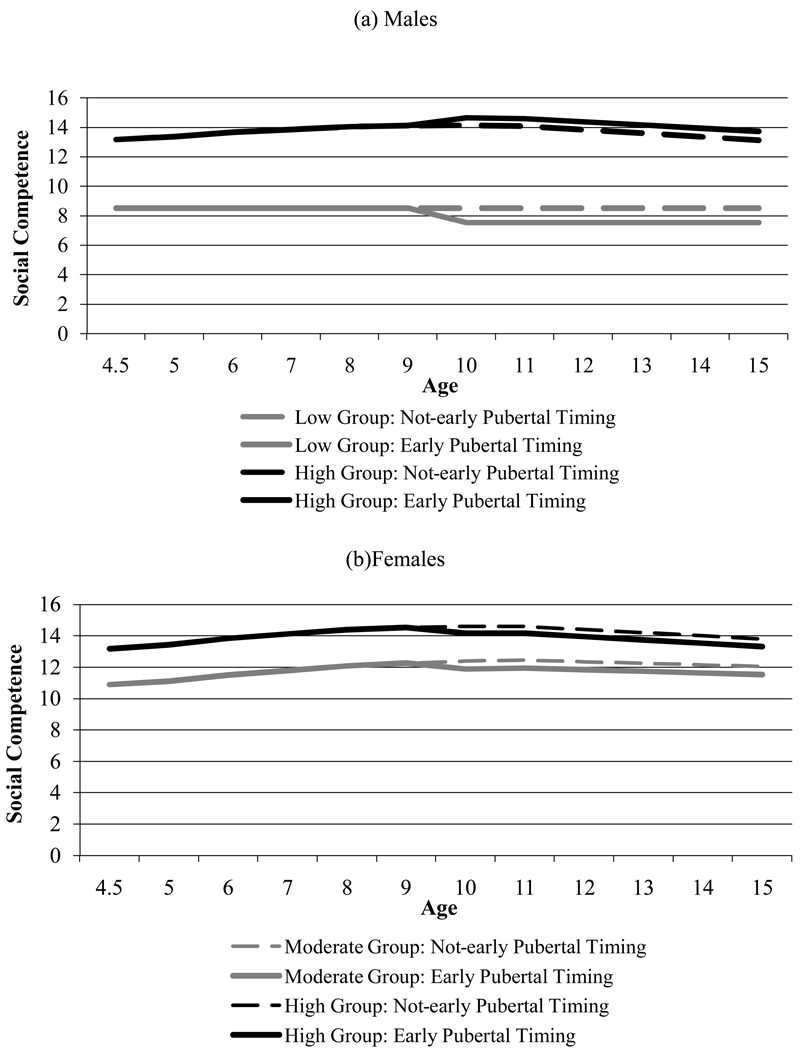

We subsequently tested whether early pubertal timing affected individuals differentially as a function of their trajectory of social competence. Among males in the low competence trajectory group, early pubertal timing had a negative impact on social competence (Table 1, Figure 2a). In contrast, early puberty was associated with an increase in social competence among males in the high social competence trajectory. There was no relation between early pubertal timing and social competence among youth in the moderate trajectory group. Among females in the moderate and high social competence trajectory groups, early puberty had a negative impact on social competence (Table 1, Figure 2b), whereas there was no relation between early pubertal timing and social competence among females in the low trajectory group.

Table 1.

Impact of Early Pubertal Timing and School Transition on Trajectories of Social Competence

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Pubertal Timing |

Early Pubertal Timing |

School Transition |

School Transition |

|

| Coefficient(SE) | Coefficient(SE) | Coefficient(SE) | Coefficient(SE) | |

| Group 1: Low Group | ||||

| Intercept | 8.50(.18)** | 9.07(.21)** | 8.52(.25)** | 9.40(.18)** |

| Linear | - | .03(.04) | - | .09(.03)** |

| Early Pubertal Timing | −.97(.47)* | −.58(.38) | - | - |

| School Transition | - | .10(.33) | −.85(.31)** | |

| Group 2: Moderate Group | ||||

| Intercept | 10.98(.14)** | 10.87(.18)** | 11.07(.17)** | 11.47(.18)** |

| Linear | .34(.06)** | .46(.06)** | .32(.06)** | .49(.06)** |

| Quadratic | −.03(.01)** | −.03(.01)** | −.03(.01)** | −.04(.01)** |

| Early Pubertal Timing | .01(.22) | −.52(.26)* | - | - |

| School Transition | - | - | .08(.23) | −.26(.23) |

| Group 3: High Group | ||||

| Intercept | 13.22(.18)** | 13.21(.15)** | 13.20(.23)** | 13.60(.23)** |

| Linear | .41(.07)** | .57(.07)** | .44(.07)** | .54(.08)** |

| Quadratic | −.04(.01)** | −.05(.01)** | −.04(.01)** | −.04(.01)** |

| Early Pubertal Timing | .66(.29)** | −.56(.26)* | - | - |

| School Transition | - | - | .07(.27) | .07(.35) |

Note. Dashes indicate that term was not estimated.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 2.

Impact of Early Pubertal Timing on Trajectories of Social Competence Among Males and Females

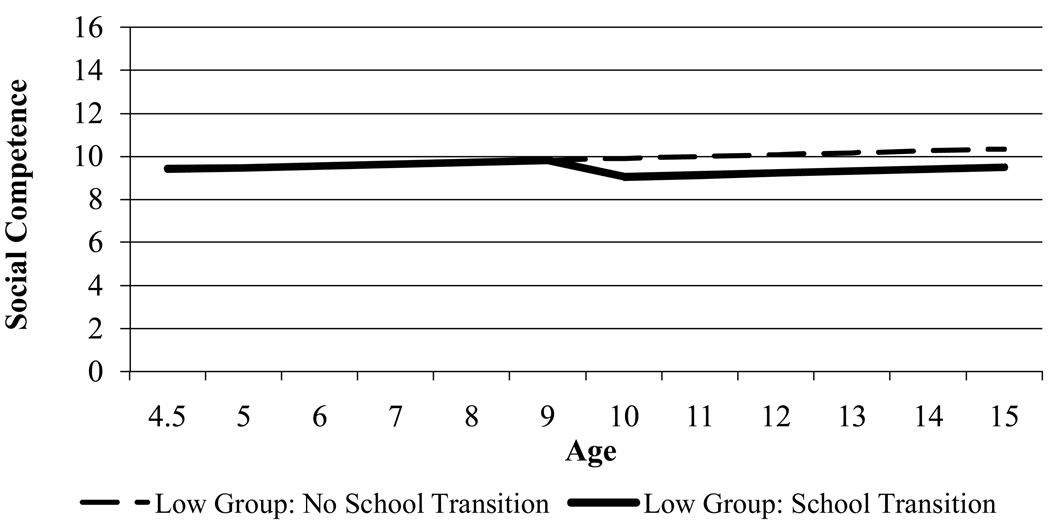

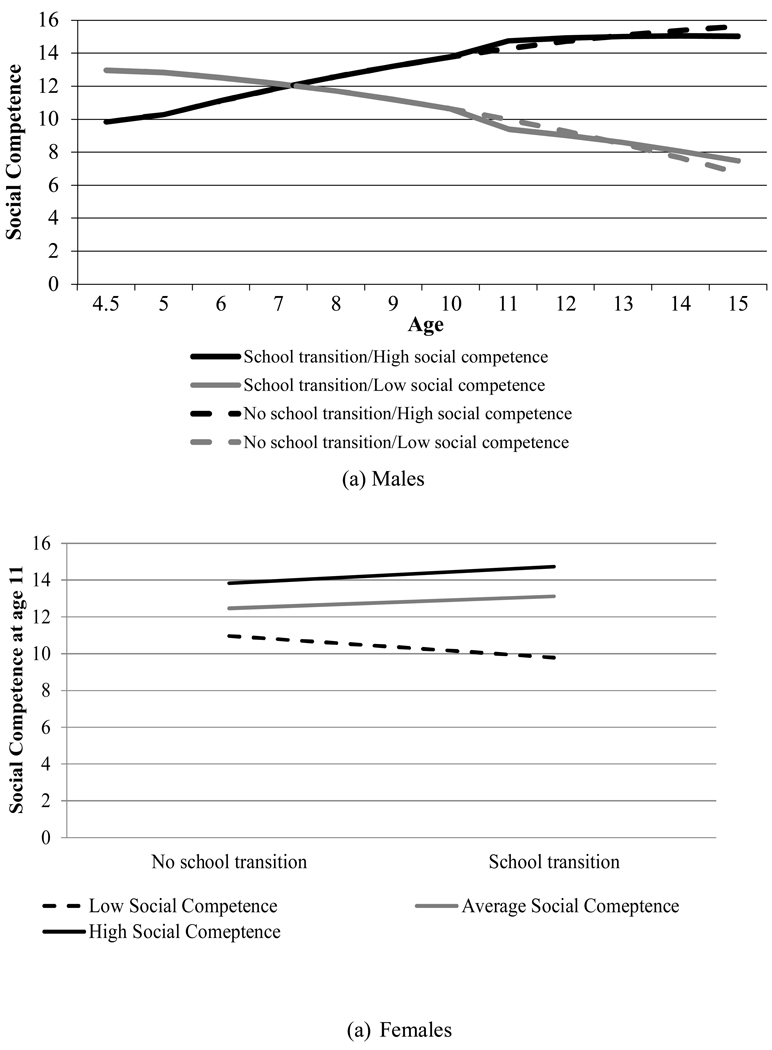

Next we examined how transitioning into middle school affected social competence (Table 1). Among males there was no effect of changing schools on social competence among youth in any of the social competence trajectories. Among females in the low social competence trajectory, experiencing a transition to middle school was associated with a decrease in social competence (Figure 3). There was no such effect, however, among females in the moderate or high social competence trajectories.

Figure 3.

Impact of School Transition on Trajectories of Social Competence Among Females

Variable-Centered Analyses

Using growth curve modeling from a multilevel modeling perspective (SAS modeling software), individual patterns of change in social competence were identified among males and females separately. First, unconditional models were used to determine the general pattern of change over time in social competence, testing for linear and quadratic growth. Growth was examined as a function of age (e.g., 6 years, 7 years, etc.) and was centered at grade 6, the assessment point that most closely corresponds to the entry into adolescence.

We subsequently tested if pubertal timing and school transition affect (a) pre-adolescent social competence (i.e., the intercept of the line) and (b) change in social competence over time (i.e., the slope of the line). To examine if the impact of pubertal timing and school transition differ as a function of level of social competence relative to other youth at the point of entry into adolescence, we tested the cross-level interaction between either pubertal timing or school transition and the adolescent’s level of social competence at age 11 relative to peers (e.g., grand mean centered social competence at age 11).

The unconditional growth models indicated both linear and quadratic growth in social competence among males and females (Table 2). Analyses indicated that there was significant variance around the intercept and linear slope, but not the quadratic term. Consequently, intercept and linear slope parameters were allowed to vary freely and the quadratic term was fixed. Pubertal timing and school transition were then used to predict variance in social competence.

Table 2.

Growth Models of Early Pubertal Timing, School Transition and Pre-Adolescent Social Competence

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional | Unconditional | Early Pubertal Timing |

Early Pubertal Timing |

School Transition |

School Transition |

|

| Effects | Coefficient (SE) |

Coefficient (SE) |

Coefficient (SE) |

Coefficient (SE) |

Coefficient (SE) |

Coefficient (SE) |

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Intercept (Mean) | 12.17(.13)** | 12.69(.12)** | 12.16(.07)** | 12.38(.07)** | 12.12(.08)** | 12.47(.07)** |

| Early Pubertal Timing (EPT) | - | - | .05(.26) | −.37(.23)** | - | - |

| School Transition (ST) | - | - | - | - | −.06(.12) | −.44(.12)** |

| Social Competence at age 11 (SC) | - | - | .73(.03)** | .77(.03)** | .72(.03)** | .64(.03)** |

| EPT X SC | - | - | .25(.10)* | .09(.08) | - | - |

| ST X SC | - | - | - | - | .17(.05)** | .26(.04)** |

| Linear slope | −.05(.02)** | −.03(.02) | −.09(.02)** | −.06(.03)** | −.10(.02)** | −.03(.02)* |

| Early Pubertal Timing (EPT) | - | - | .20(.22) | −.24(.19)** | - | - |

| School Transition (ST) | - | - | - | - | .03(.01)** | .03(.01)** |

| Social Competence at age 11 (SC) | - | - | .03(.01)** | .06(.01)** | .19(.05)** | −.17(.08)** |

| EPT X SC | - | - | .18(.10) | .16(.07)** | - | - |

| ST X SC | - | - | - | - | −.10(.02)** | >−.01(.03) |

| Quadratic slope | −.03(>.01)** | −.03(>.01)** | −.03(>.01)** | −.03(>.01)** | −.03(>.01)** | −.03(>.01)** |

| Random effects | - | |||||

| Intercept | 3.67(.36)** | 3.73(.33)** | .49(.11)** | .50(.10)** | .68(.10)** | .68(.09)** |

| Linear slope | .03(.01)** | .04(.01)** | .03(.01)** | .04(.01)** | .03(.01)** | .03(.01)** |

| Level-1 error | 2.42(.09)** | 2.36(.08)** | 2.33(.09)** | 2.21(.08)** | 2.30(.08)** | 2.29(.08)** |

| Model Fit | ||||||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 8578.4 | 9974.7 | 6968.4 | 8206.5 | 7889.9 | 9236.5 |

| AIC | 8592.4 | 9988.7 | 6994.4 | 8232.5 | 7915.9 | 9262.5 |

| BIC | 8617.8 | 10014.9 | 7041.2 | 8281.0 | 7962.7 | 9311.0 |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

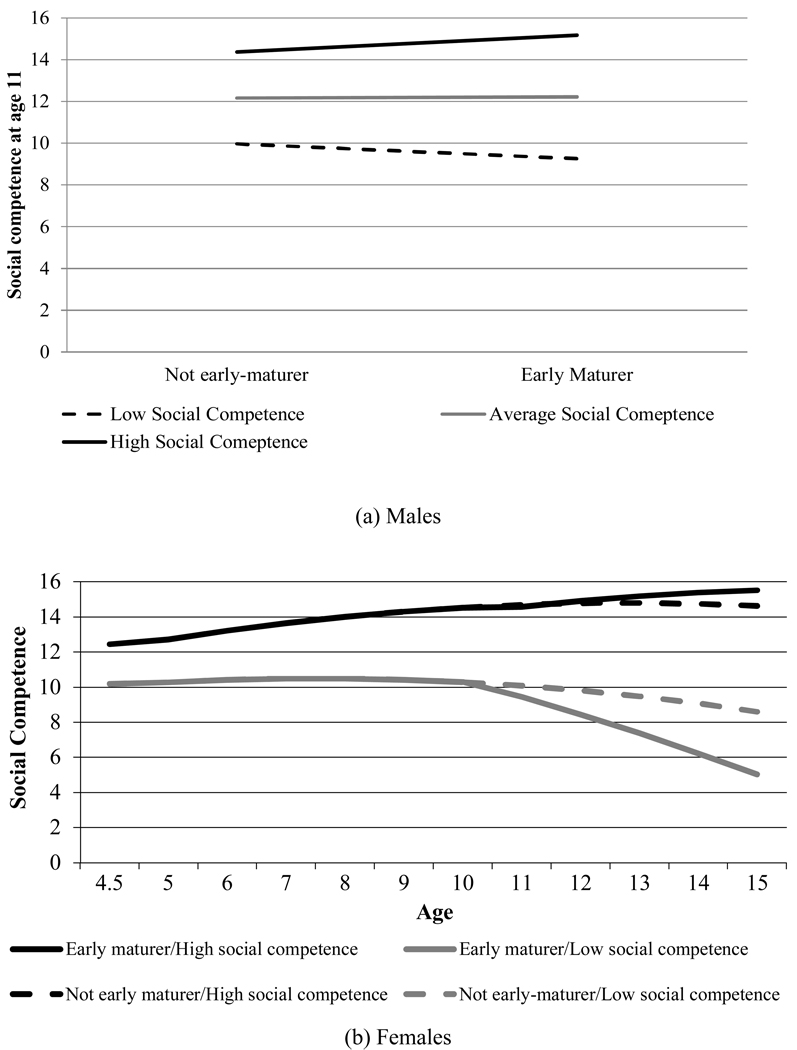

Among males, there was a significant interaction between early pubertal timing and pre-adolescent social competence (Table 2). Among males with higher pre-adolescent social competence relative to peers, early pubertal timing was associated with greater social competence at age 11 (Figure 4a). In contrast, among less competent pre-adolescent males, early maturation was associated with lower social competence. Although the interaction between pubertal timing and relative social competence did not predict differences in the intercept of social competence among females, the interaction between pubertal timing and relative social competence predicted differences in the rate at which girls’ social competence developed over time (Figure 4b). Among less competent pre-adolescent females, early maturers declined rapidly in social competence, whereas among more competent females, early maturation was associated with increases in social competence over time.

Figure 4.

Impact of Early Pubertal Timing and Pre-Adolescent Social Competence on Trajectories of Social Competence Among Males and Females

A parallel set of analyses tested if the impact of school transition on social competence varied as a function of a youth’s pre-adolescent level of social competence (Table 2). More competent males showed greater social competence after a school transition, whereas less competent males showing diminished social competence after a school transition (Figure 5a). However, these effects disappear over time, suggesting that the accentuation of individual differences in competence during a school transition is brief. Females with high social competence in pre-adolescence who experienced a school transition showed greater social competence (Figure 5b), whereas undergoing a school transition was associated with diminishing social competence among less competent females. In contrast to males, however, these effects among females do not appear to dissipate over time.

Figure 5.

Impact of School Transition and Pre-Adolescent Social Competence on Trajectories of Social Competence Among Males and Females

Analyses of the impact of early puberty and transitioning to middle school were repeated with both potential stressors in the equation simultaneously. Among males, the pattern of results remained unchanged, indicating that that each experience contributes to social competence. Among females, there was evidence that the effects of early pubertal maturation and school transition were cumulative. Experiencing early pubertal maturation and school transition simultaneously was associated with diminished social competence, an effect that was strongest among less competent females.

Discussion

The present findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that early pubertal timing (Ge et al., 2002; Simmons & Blyth, 1987) and school transition (Berndt et al., 1999; Proctor & Choi, 1994) are linked to both positive and negative outcomes. We find that early pubertal maturation and school transition do not radically shift pre-existing trajectories but, rather, lead to an accentuation of individual differences, with the most competent youth becoming increasingly so and the least competent youth becoming less so as they negotiate these developmental transitions. Indeed, the overall pattern is suggestive of an accentuation of individual differences similar to that described by Caspi and colleagues (Caspi & Moffitt, 1993). To the extent that social competence acts as a protective factor for positive development, and as an indicator of resilience in the face of stressors, highly competent youth may benefit from moderately stressful experiences that elicit and perhaps strengthen their social skills, whereas less competent youth become even less so in the face of this same challenges.

Of particular note in the present study is that variable- and person-centered analyses generally yield the same findings. In our variable-centered models, we identified statistically significant groups of individuals on the basis of their level of social competence over time. In our person-centered analyses, we examined heterogeneity in both level and rate of change in social competence over time, treating social competence as a continuous variable. Notably, whereas the pattern of findings regarding school transitions was similar among males and females (high social competence is a protective factor, whereas low competence worsens the impact of the transition), the pattern with respect to early puberty was not. Among boys high in preadolescent social competence, early maturation has positive consequences. Consistent with previous research on the potential negative impact of early puberty on girls’ mental health, we find some evidence that early maturation may have immediate negative effects among females, but over time, is associated with negative consequences only for less competent females. Finally, although the independent effects of pubertal timing and school transition were positive among more competent females, when early pubertal maturation and school transition occur currently, there is evidence that females decrease in social competence. It may be that a low amount of stress leads to the individual accentuation of differences, but that simultaneous exposure to multiple stressors is uniformly negative (Sameroff, 2000), although high social competence diminishes the strength of this effect.

The present study is limited in several respects. Foremost, while maternal reports are known to be reliable and valid measures of social competence in early and middle childhood (Masten et al., 1995; Obradovic et al., 2006), they are not commonly used to assess competence in adolescence (most researchers rely on adolescents’ self-reports). It is also the case that the correlations between our age-specific measure and the age-variant measures were modest. However, these correlations, coupled with the significant correlation found between maternal report and adolescent self-report of social competence, suggest that our measure of social competence is valid. Second, we were only able to examine school transitions among public school youth; to the extent that school transitions vary in timing between public and private schools, it remains an important question for future research how transitions at other time points in adolescence might impact social competence across adolescence. Third, although individuals from the present study are drawn from across the country, the SECCYD sample is generally high functioning, and the difference between relatively higher and lower social competence may be attenuated. Moreover, our sample size may have limited the ability to detect heterogeneity in social competence.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that, rather than deflecting trajectories of competence, developmental transitions such as puberty or switching schools accentuate individual differences. Thus, the popular notion that maturing physically or changing schools gives individuals a chance to make a “fresh start” may be incorrect. It is clear, given the effects found across multiple types of data analyses, that the impact of developmental transitions on social competence differ among youth as a function of their level of social competence at the time of the transition. To the extent that this is a common effect, seen across other types of transitions not studied here, it appears that in the face of the normative developmental challenges adolescence, the psychosocially rich become richer, while the psychosocially poor lose further ground.

Acknowledgements

This study is directed by a Steering Committee and supported by NICHD through a cooperative agreement (U10), which calls for scientific collaboration between the grantees and the NICHD staff. The content is solely the responsibility of the named authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institutes of Health, or individual members of the Network. Current members of the Steering Committee of the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (in alphabetical order) are Jay Belsky (Birkbeck University of London), Cathryn Booth-LaForce (University of Washington), Robert H. Bradley (University of Arkansas at Little Rock), Celia A. Brownell (University of Pittsburgh), Margaret Burchinal (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), Susan B. Campbell (University of Pittsburgh), Elizabeth Cauffman (University of California, Irvine), Alison Clarke-Stewart (University of California, Irvine), Martha Cox (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), Robert Crosnoe (University of Texas, Austin), James A. Griffin (NICHD Project Scientist and Scientific Coordinator), Bonnie Halpern-Felsher (University of California, San Francisco), Willard Hartup (University of Minnesota), Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek (Temple University), Daniel Keating (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), Bonnie Knoke (RTI International), Tama Leventhal (Tufts University), Kathleen McCartney (Harvard University), Vonnie C. McLoyd (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), Fred Morrison (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), Philip Nader (University of California, San Diego), Marion O’Brien (University of North Carolina, Greensboro), Margaret Tresch Owen (University of Texas, Dallas), Ross Parke (University of California, Riverside), Robert Pianta (University of Virginia), Kim M. Pierce (University of Wisconsin–Madison), A. Vijaya Rao (RTI International), Glenn I. Roisman (University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign), Susan Spieker (University of Washington), Laurence Steinberg (Temple University), Elizabeth Susman (Pennsylvania State University), Deborah Lowe Vandell (University of California, Irvine), and Marsha Weinraub (Temple University). The age 15 data assessment of the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development was supported via the following grants from the NICHD: 5U10HD025460-18, 5U10HD0 25447-18, 5U10HD025420-19, 5U10HD025456-18, 5U10HD025445-19, 5U01HD033343-14, 5U10HD025451-19, 5U10HD025430-18, 5U10HD0 25449-18, 5U10HD027040-18, and 5U10HD025455-18.

Footnotes

The number of youth experiencing a school transition varied over time: between 3rd and 4th grades, 3% of males and 4% of females experienced a transition; between 4th and 5th grades, 2% of males and 3% of females experienced a transition; between 5th and 6th grades 8% of males and 7% of females experienced a transition; between 6th and 7th grades 54% of males and 54% of females experienced a school transition.

In the 4-group solutions for males and females, the additional group showed high quadratic patterns of growth, increasing throughout middle childhood and decreasing slightly across the transition to adolescence.

Contributor Information

Kathryn C. Monahan, Social Development Research Group, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 9725 3rd Ave NE, Suite 401, Seattle, WA 98115-2024

Laurence Steinberg, Department of Psychology, Weiss Hall, 1701 N. 13th Street, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122.

REFERENCES CITED

- Berndt TJ, Hawkins JA, Jiao Z. Influences of friends and friendships on adjustment to junior high school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45(1):13–41. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence. Psychological Inquiry. 1993;4(4):247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Rose AJ. Understanding popularity in the peer system. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, Murray VM. Contextual amplification of pubertal transition effects on deviant peer affiliation and externalizing behavior among African American children. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:42–54. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Nichols TR, Birnbaum AS, Botvin GJ. Social competence among urban minority youth entering middle school: Relationships with alcohol use and antisocial behaviors. International Journal of Adolescent Medical Health. 2006;18(1):97–106. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2006.18.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Profilet SM. The Child Behavior Scale: A teacher-report measure of young children’s aggressive, withdrawn, and prosocial behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(6):1008–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Little T, Jones S, Henrich C, Hawley P. Disentangling the “whys” from the “whats” of aggressive behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Neemann J, Gest SD, Tellegen A, Garmezy N. The structure and coherence of competence from childhood through adolescence. Child Development. 1995;66:1635–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Child care and child development: Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. NY: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic J, van Dulmen MHM, Yates TM, Carlson EA, Egeland B. Development assessment of competence from early childhood to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29:847–889. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(4):611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor TB, Choi HS. Effects of transition from elementary school to junior high school on early adolescents’ self-esteem and perceived competence. Psychology in the Schools. 1994;31(4):319. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Developmental systems and psychopathology. Developmental and Psychopathology. 2000;12:297–312. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RG, Blyth DA. Moving into adolescence: The impact of pubertal change and school context. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1987. [Google Scholar]