Abstract

Aims: To ascertain the views of general practitioners (GPs) regarding the prevention and management of alcohol-related problems in practice, together with perceived barriers and incentives for this work; to compare our findings with a comparable survey conducted 10 years earlier. Methods: In total, 282 (73%) of 419 GPs surveyed in East Midlands, UK, completed a postal questionnaire, measuring practices and attitudes, including the Shortened Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire (SAAPPQ). Results: GPs reported lower levels of post-graduate education or training on alcohol-related issues (<4 h for the majority) than in 1999 but not significantly so (P = 0.031). In the last year, GPs had most commonly requested more than 12 blood tests and managed 1–6 patients for alcohol. Reports of these preventive practices were significantly increased from 1999 (P < 0.001). Most felt that problem or dependent drinkers' alcohol issues could be legitimately (88%, 87%) and adequately (78%, 69%) addressed by GPs. However, they had low levels of motivation (42%, 35%), task-related self-esteem (53%, 49%) and job satisfaction (15%, 12%) for this. Busyness (63%) and lack of training (57%) or contractual incentives (48%) were key barriers. Endorsement for government policies on alcohol was very low. Conclusion: Among GPs, there still appears to be a gap between actual practice and potential for preventive work relating to alcohol problems; they report little specific training and a lack of support. Translational work on understanding the evidence-base supporting screening and brief intervention could incentivize intervention against excessive drinking and embedding it into everyday primary care practice.

INTRODUCTION

Excessive drinking has a substantial global impact on public health and is the second greatest risk to health and well-being in developed countries (Rehm et al., 2003; World Health Organisation, 2005, 2009; Rehm et al., 2009). In England, 38% of men and 16% of women (8.2 million adults) are hazardous, harmful or dependent drinkers (collectively known as excessive drinkers) (Drummond et al., 2005). Moreover, deaths in the UK from alcohol-related liver cirrhosis and alcohol attributable disorders have increased markedly over the last 50 years compared with those from heart disease (World Health Organisation, 2004). Preventive approaches, particularly screening and brief interventions (SBI), are cost-effective and have the potential to benefit over 7 million hazardous or harmful drinkers in the UK by reducing their risk of escalating alcohol-related harm or dependency (Raistrick et al., 2006). Primary care is ideal for early detection and secondary prevention of excessive drinking due to its high contact-exposure to the population: one-fifth of routinely presenting patients are likely to be excessive drinkers, presenting at twice the rate of average patients and with a wide range of alcohol-related problems (Anderson, 1996; Kaner et al., 2001). Moreover, a large and robust evidence-base has reported that brief interventions are effective at reducing excessive drinking in primary care patients (Raistrick et al., 2006; Kaner et al., 2007), and they have been piloted in the UK in primary and secondary healthcare settings to tackle the rising alcohol consumption (Department of Health, 2004, 2007). Yet, a recent national report found a lack of real progress on alcohol intervention work in primary care despite sharply rising costs due to this public health problem of formal identification and intervention with, or referral of, patients with alcohol use (Health Care Commission Audit Commission, 2008). A national alcohol needs assessment reported that general practitioners (GPs) exhibit low levels of formal identification and intervention with, or referral of, patients with alcohol-use disorders (Drummond et al., 2005). Indeed in 1999, it was reported that GPs were likely to be missing as many as 98% of the excessive drinkers presenting to primary health care (Kaner et al., 1999). GPs indicated at that time that they were prepared to counsel patients about reducing alcohol consumption but perceived a lack of effectiveness in doing so. They were little involved in, and poorly motivated to work with, alcohol issues, and they focused on physical symptoms to identify alcohol problems (Deehan et al., 1998a, b; Kaner et al., 1999; McAvoy et al., 1999).

GPs are pivotal to the delivery of any initiative in primary care and their attitudes towards interventions are therefore likely to determine the impact achieved. Given the rise of alcohol-related harm in the public policy agenda in the UK, it is important to reassess GPs' attitudes and practices regarding intervention against excessive alcohol use, to indicate why this key strategy for tackling excessive drinking may not be achieving its potential. This paper reports on a recent survey of English GPs carried out in the same area as the study from 1999 with the aims of evaluating current knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning alcohol, and examining whether these have changed since the study 10 years ago.

METHODS

Conducted in 2009, the present study used a comparable method and questionnaire to a postal survey of GPs in 1999 (Kaner et al., 1999; McAvoy et al., 1999). The sample consisted of one GP principal randomly sampled from each of 419 practices identified in six Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. This was the same geographical area studied in the previous survey. Details of general practices were provided either directly by the PCT or via the NHS Choices website (http://www.nhs.uk).

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used (see supplementary material) was a modified version of the questionnaire from the 1999 survey (Kaner et al., 1999; McAvoy et al., 1999). It gathered demographic data and practice information. GPs were asked—in an open-ended question—what conditions typically led them to talk to a patient about alcohol and, on a scale of one to four, how often they enquired about alcohol if a patient did not mention it (‘all the time’ to ‘rarely or never’). The Shortened Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Perception Questionnaire (SAAPPQ) (Anderson and Clement, 1987) was included to measure GPs' disposition towards intervening for alcohol problems: five pairs of items give measures of adequacy, task-specific self-esteem, motivation, legitimacy and satisfaction (Anderson et al., 2004a). These items were asked separately in respect of hazardous or harmful (‘problem’) drinkers and dependent drinkers. Respondents also indicated their agreement on a scale of one to four (‘not at all’ to ‘very much’), with 15 suggested barriers and seven suggested incentives to early intervention for alcohol in general practice. They rated the effectiveness of 12 government measures and 11 suggested policies to tackle alcohol problems on a scale from one to five (1 = no opinion, 2 = ineffective, 3 = slightly effective, 4 = quite effective, 5 = very effective).

Measures to ensure adequate response rates (Kaner et al., 1998; Edwards et al., 2007) included personalized pre-notification and follow-up letters signed by the GP member of the research team (P.C.), telephone calls to non-responders to ask whether they would return the questionnaire and an unconditional £10 voucher to compensate GPs for their time. All documents were posted between 25 June 2009 and 7 September 2009, which included a period of school holidays and occurred during concern about the swine flu pandemic. Each questionnaire contained a unique ID number, which could be matched to GP contact details stored on a secure server in a separate database.

Analysis

SPSS statistical software, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, 2009) was used to calculate means as well as standard deviations and to run paired or unpaired t-tests for continuous variables, and frequency distributions and χ2 tests for categorical data. Since a large number of tests were carried out, increasing the likelihood of false positives, a P-value of 0.01 was taken as a more conservative threshold for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Response rates

34 GPs (8%) were not eligible to complete the survey because they had left practice, retired, or taken maternity or long-term sick leave. Of the 385 eligible GPs, 282 (73%) responded to the survey, compared with 68% (279 out of 411) in the 1999 survey. There was no significant difference between response rates for the current and the previous survey (χ2(1) = 2.75, P = 0.097). Just 10 (3%) respondents in 2009 thought they had responded to the questionnaire in 1999; hence the two samples were regarded as independent. Response rates for each of the three areas were similar (77% from Leicester City and Leicestershire County, 68% from Derby City and Derbyshire County and 74% from Nottingham City and Nottinghamshire County).

Sample characteristics

Characteristics of the GP sample and practices are shown in Table 1. The age of GPs in the 2009 study ranged from 28 to 74 years. They had practiced for between half a year and 42 years. The mean number of full-time employed GPs at the practices was four (SD 2.15); the modal number was two. Fifteen per cent of GPs worked as sole practitioners. Male GPs had spent significantly more years in practice than female GPs (5.5 years, 95% CI 3.3–7.5; P < 0.001), and they reported working significantly more days per week in practice than female GPs (0.7, 95% CI 0.5–1.0; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

GP and practice characteristics in 2009 and 1999

| Measure | 2009 sample | 1999 sample |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 47 years (9.25) | 51 years (8.51) |

| % male | 57 | 76 |

| Mean years in practice (SD) | 16 (9.19) | 13 (8.30) |

| Mean days in practice/week (SD) | 4.2 (1.03) | 5.3 (1.03) |

| Modal category patients seen/week (%) | 100–150 (50) | >150 (48) |

| % urban practices | 50% | 50% |

| % group practices | 86% | 78% |

| Mean no. practice partners (SD) | 3.9 (2.15) | 3.4 (1.88) |

There were significantly more female doctors in the 2009 sample (43%, 121) than in the 1999 sample (24%, 57) (χ2(1) = 19.75, P < 0.001); the average age of respondents in 2009 was significantly lower than in 1999 (4.3 years, 95% CI 2.8–5.9; P < 0.001). GPs in 2009 had been in practice for significantly longer than GPs in the 1999 study (3.2 years, 95% CI 1.6–4.7; P < 0.001), and they spent fewer days per week in practice than GPs in the 1999 sample (1.1, 95% CI 0.9–1.3; P < 0.001). The number of patients seen per week was significantly different between the surveys (χ2(3) = 64.95, P < 0.001), with a trend towards fewer patients seen per week in the later survey. Modal values were ‘101–150 patients per week’ in 2009 compared with ‘>150 patients per week’ in 1999.

Medical education and training on alcohol

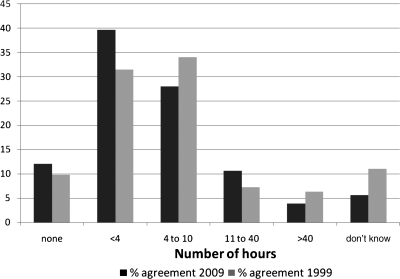

Around half of the GPs (52%, 146) indicated that they had received <4 h of post-graduate training, continuing medical education or clinical supervision on alcohol and alcohol-related problems, including 34 GPs who said that they had received no such training. This proportion was not significantly different from that reported in 1999 (χ2(5) = 12.31, P = 0.031; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Number of hours of post-graduate training, continuing medical education or clinical supervision on alcohol.

Current management of excessive drinkers

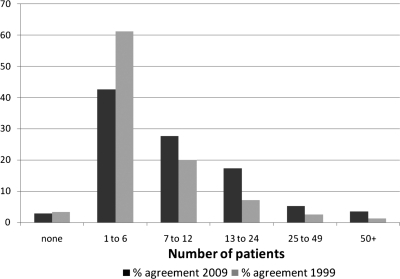

Figure 2 demonstrates a significant trend towards more requests for blood tests for alcohol in 2009 compared with those in 1999 (χ2(4) = 46.24, P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in either of these measures between male and female doctors or between older and younger GPs. Moreover, there was a significant trend towards more patients being managed for alcohol problems in 2009 compared with those in 1999 (χ2(5) = 27.35, P < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Number of times a blood test was taken or requested because of alcohol.

Fig. 3.

Number of patients managed specifically for alcohol problems per year.

Asking about alcohol use

The largest proportion of GPs (58%, 163) said that they enquired about alcohol ‘some of the time’ if the patient did not volunteer information, whereas 40% (113) said that they did this most or all of the time. Frequency of enquiring about alcohol did not differ significantly between male and female GPs (χ2(3) = 8.59, P = 0.035), but it was significantly different between older and younger GPs (χ2(3) = 24.92, P < 0.001), with a trend for older GPs to ask more frequently than younger GPs. There was a significant difference in responses to this question between 2009 and 1999 (χ2(3) = 16.07, P = 0.001), with a trend towards patients being asked more of the time in the later year. GPs' open responses as to what typically led them to enquire about alcohol were coded as physical, psychological (e.g. depression, anxiety, stress or mood disorders), social or other conditions (e.g. health checks, medication reviews). The majority of GPs responded with combinations of these categories; however, 22% (63) listed no psychological or social problems as triggers to enquiry, including 13% of GPs (37) who gave only physical conditions.

Attitudes to working with different types of drinker

Results from the five categories of the SAAPPQ are summarized in Table 2. High proportions of GPs agreed that it was legitimate for them to ask either problem drinkers (88%) or dependent drinkers (87%) about their alcohol consumption. Seventy-eight per cent agreed that they had adequate training and knowledge to work with problem drinkers and 69% with respect to dependent drinkers; this difference was significant (0.48 mean difference, 95% CI 0.33–0.63; P < 0.001). More GPs felt adequately trained and knowledgeable to intervene for alcohol in 2009 than in 1999; this trend was significant in respect of work with both problem drinkers (0.44, 95% CI 0.13–0.75; P = 0.006) and dependent drinkers (0.53, 95% CI 0.17–0.90; P = 0.004).

Table 2.

SAAPPQ results: 2009–1999 comparison

| SAAPPQ component | % agree 2009 | % agree 1999 | t | df | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With problem drinkers: | |||||

| Legitimacy | 88 | 87 | 0.126 | 501 | 0.900 |

| Adequacy | 78 | 72 | −2.756 | 496 | 0.006 |

| Motivation | 42 | 23 | −2.445 | 497 | 0.015 |

| Self-esteem | 53 | 20 | 0.303 | 495 | 0.762 |

| Satisfaction | 15 | 13 | −1.469 | 501 | 0.143 |

| With dependent drinkers: | |||||

| Legitimacy | 87 | 87 | 0.091 | 501 | 0.927 |

| Adequacy | 69 | 61 | −2.882 | 499 | 0.004 |

| Motivation | 35 | 24 | −3.182 | 499 | 0.002 |

| Self-esteem | 49 | 28 | −1.729 | 493 | 0.084 |

| Satisfaction | 12 | 7 | −2.198 | 500 | 0.028 |

GPs reported comparatively low levels of motivation (43% agreement), self-esteem (53%) and satisfaction (15%) arising from work with problem drinkers; motivation, satisfaction and self-esteem were lower again (35, 49 and 12% agreement, respectively) in relation to working with dependent drinkers. GPs were significantly less motivated to work with dependent drinkers than with problem drinkers (0.38 mean difference, 95% CI 0.24–0.47; P < 0.001), as well as less satisfied (0.51, 95% CI 0.39–0.64; P < 0.001). Motivation to work with dependent drinkers was significantly greater in 2009 than in 1999 (0.27, 95% CI 0.22–0.94; P = 0.002). No other significant differences were observed between SAAPPQ scores relating to problem and dependent drinkers or across the two surveys.

Perceived barriers and facilitating factors influencing early alcohol intervention

The highest rated barriers to early intervention for alcohol-related problems were that doctors were ‘just too busy’ (63% agreement, 178); that they were not trained in alcohol counselling techniques (57% agreement, 160); and that the current General Medical Services (GMS) contract did not encourage GPs to work with alcohol problems (48% agreement, 136; Table 3). The most strongly endorsed facilitating factors were: readily available support services (87% agreement, 246), evidence of the successful impact of early intervention (81% agreement, 229) and requests from patients for health advice about alcohol (80% agreement, 225; Table 4).

Table 3.

Suggested barriers to intervening for alcohol

| Perceived barrier | 2009 % agreement | 1999 % agreement | t | df | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors are just too busy dealing with the problems people present with | 63 | 69 | 1.973 | 491 | 0.049 |

| Doctors are not trained in counselling for reducing alcohol consumption | 57 | 58 | 0.957 | 487 | 0.339 |

| aDoctors are not sufficiently encouraged to work with alcohol problems in the current GMS contract | 48 | - | - | - | - |

| Doctors do not have suitable counselling materials available | 46 | 47 | 0.760 | 486 | 0.448 |

| Doctors believe that alcohol counselling involves family and wider social effects, and is therefore too difficult | 41 | 48 | 1.658 | 484 | 0.098 |

| Doctors do not believe that patients would take their advice and change their behaviour | 39 | 49 | 2.613 | 485 | 0.009 |

| Doctors do not know how to identify problem drinkers who have no obvious symptoms of excess consumption | 30 | 29 | 0.773 | 490 | 0.440 |

| Doctors themselves may have alcohol problems | 28 | 38 | 3.136 | 485 | 0.002 |

| Doctors do not have a suitable screening device to identify problem drinkers who have no obvious symptoms of excess consumption | 28 | 38 | 3.111 | 484 | 0.002 |

| Doctors themselves have a liberal attitude to alcohol | 27 | 40 | 3.996 | 487 | <0.001 |

| Doctors think that preventive health should be the patients' responsibility not theirs | 23 | 38 | 4.620 | 489 | <0.001 |

| Doctors feel awkward about asking questions about alcohol consumption because saying someone has an alcohol problem could be seen as accusing them of being an alcoholic | 22 | 23 | 0.135 | 488 | 0.893 |

| Doctors have a disease model training and they don't think about prevention | 21 | 40 | 4.443 | 488 | <0.001 |

| Doctors believe that patients would resent being asked about their alcohol consumption | 17 | 20 | 0.468 | 486 | 0.640 |

| Alcohol is not an important issue in general practice | 14 | 28 | 4.760 | 491 | <0.001 |

aModified from ‘The government health scheme does not reimburse doctors for time spent on preventive medicine’ – not compared with 1999 here.

Table 4.

Suggested incentives to intervening for alcohol[]

| Perceived incentive | 2009 % agreement | 1999 % agreement | t | df | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aGeneral support services (self-help/counselling) were readily available to refer to | 87 | 80 | −1.407 | 495 | 0.160 |

| Early intervention for alcohol was proven to be successful | 81 | 75 | −0.428 | 495 | 0.669 |

| Patients requested health advice about alcohol consumption | 80 | 72 | −1.748 | 495 | 0.081 |

| Quick and easy counselling materials were available | 76 | 56 | −4.377 | 492 | <0.001 |

| Quick and easy screening questionnaires were available | 70 | 48 | −4.717 | 493 | <0.001 |

| Training programmes for early intervention for alcohol were available | 69 | 53 | −3.400 | 492 | 0.001 |

| Public health education campaigns in general made society more concerned about alcohol | 66 | 61 | −0.586 | 495 | 0.558 |

| bProviding early intervention for alcohol was included in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) | 63 | 33 | −6.798 | 493 | <0.001 |

| Salary and working conditions were improved | 39 | 56 | 4.478 | 492 | <0.001 |

aModified from ‘Support services were readily available to refer patients to’.

bModified from ‘Training in early intervention for alcohol was recognized for continuing medical education credits’.

Comparing data from 2009 and 1999, significantly fewer GPs in the current survey reported feeling that patients would not heed their advice, that GPs had a disease model training, that GPs were not responsible for preventive health or lacked a suitable screening tool for alcohol or that GPs' own use of, and attitudes to, alcohol were barriers. Moreover, significantly more GPs in 2009 reported that early intervention could be encouraged by the provision of screening and intervention materials as well as training in behaviour change techniques.

GPs' views on policy to reduce alcohol-related harm

A relatively low proportion of GPs endorsed the range of current government policies on alcohol (Table 5). Consistently across the battery of policies, 75% or more GPs perceived these policies as ineffective. Relatively high proportions of GPs perceived other potential policies as more effective in reducing alcohol-related harm (Table 6). In total, 71% of GPs (199) considered that improved alcohol education in schools would be effective, while 58% (162) endorsed further regulation of off-sales and 55% (155) thought minimum pricing for units of alcohol would be effective.

Table 5.

GPs' agreement with effectiveness of government policies in reducing alcohol-related harm

| Policy | Very effective or quite effective % agreement |

|---|---|

| Increased provision for treatment of alcohol problems | 25% |

| Introduction of powers to ban anti-social drinking in areas | 24% |

| Introduction of powers to ban individuals from premises/areas following alcohol-related anti-social behaviour | 22% |

| Increased provision for brief interventions to prevent alcohol problems | 20% |

| Promotion of recommended guidelines on drinking limits and health information | 18% |

| Increased powers to enforce and penalize breach of licence conditions | 18% |

| Sharpened criminal justice for drunken behaviour | 18% |

| Introduction of local alcohol strategies | 17% |

| Stricter rules for the content of alcohol advertisements | 13% |

| More extensive considerations when granting licenses | 13% |

| Promotion of a ‘sensible drinking’ culture | 11% |

| Introduction of more flexible opening hours licensed premises | 5% |

Table 6.

GPs' agreement with potential effectiveness of suggested policies in reducing alcohol-related harm

| Policy | Effective or very effective % agreement |

|---|---|

| Improve alcohol education in schools | 71% |

| Further regulation of alcohol off-sales (e.g. supermarkets, off-licences) | 57% |

| Institute minimum pricing for units of alcohol | 55% |

| Increase restrictions on TV & cinema alcohol advertising | 54% |

| Lower blood alcohol concentration limit for drivers | 53% |

| Make public health a criterion for licensing decisions | 49% |

| Raise minimum legal age for purchasing alcohol | 48% |

| General changes in alcohol price through taxation | 48% |

| Statutory regulation of alcohol industry | 43% |

| Raise minimum legal age for drinking alcohol | 39% |

| Government monopoly of retail sales of alcohol | 27% |

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that routine enquiry about alcohol still does not appear to be a mainstream practice among English GPs. Trends in enquiry about alcohol use are increasing, but rates of preventive practice and post-graduate training specifically on alcohol are still low, and psychological or social problems do not elicit enquiry about alcohol from all GPs. GPs on the whole feel that they could and should intervene for alcohol, particularly with problem drinkers, but fewer feel motivated or satisfied to work with either problem drinkers or dependent drinkers, or associate this with self-esteem (Anderson et al., 2003). This pattern of GPs feeling secure to intervene for alcohol but reporting low levels of training, support and therapeutic commitment is similar to that obtained 10 years previously. GPs perceive themselves facing more practical limitations on preventive practice than attitudinal ones, particularly being too busy and not being supported by their contract. Around half of GPs agreed that lack of training, intervention materials and support for counselling were barriers to early intervention for alcohol, with strong support for the availability of general support (self-help or counselling) and health education campaigns as incentives. Respondents showed little support for previous government policies to tackle alcohol; the highest rating of effectiveness was from just a quarter of GPs for the increased provision of treatment for alcohol problems, while the introduction of flexible opening hours was seen as effective by only 5% of GPs. What GPs want to see most is better education about alcohol in schools, with substantial support for more regulation of off-sales and minimum pricing for units of alcohol.

The response rate of 73%, from a large and systematically sampled population of GPs similar to that of the 1999 study, exceeds those in recent surveys of GPs in other countries (Holmqvist et al., 2008; Nygaard et al., 2010) despite conclusions that response rates from GPs are in decline (Cummings et al., 2001; Cook et al., 2009). This is encouraging given the impact of school holidays and a national flu pandemic during the data collection period, and gives these findings strong external validity (Burns et al., 2008). Growing concern about alcohol among GPs may have contributed to this response; many wrote at the end of their questionnaire expressing concern about patients' alcohol misuse with one offering thanks for the chance to express their views. The replication of materials and target population from the previous study meant that some questions gathered only categorical data, but this enabled a robust comparison over a decade and enhanced the comparability of these findings with other studies. The 2009 sample displayed a profile similar to that of English GPs as a whole, of whom 60% were male, 37% were aged 40–49 and 28% were aged 50–59 in 2006 (Royal College of General Practitioners, 2006). However, five per cent of the national workforce were in sole practice compared with 15% of this sample (Royal College of General Practitioners, 2006), which reflects characteristics of the local population. The reductions in hours worked and numbers of patients since 1999 probably reflect a number of factors: the increased proportion of female GPs, who were more likely to work part-time; the transfer of activity between surveys from secondary to primary care of patients; the move to a greater skill mix within practices; and more patients with complex conditions being seen in primary care (NHS Workforce Review Team, 2008). Limitations of the research include the self-reported nature of the data, which are therefore subject to socially desirable responding. For instance, preventive approaches may have been perceived as socially desirable and therefore endorsed to a greater extent than reported levels of practice suggest. However, we sought to minimize any such effects through inviting responses on an anonymous basis. The numbers of patients GPs report managing for alcohol problems are commensurate with rates reported elsewhere for prevalence and treatment of alcohol dependence in primary care (Drummond et al., 2005), suggesting some respondents may only have counted patients whose problems required lengthy specialist intervention.

While preventive work in primary care can be effective in reducing excessive alcohol consumption (Raistrick et al., 2006; Kaner et al., 2007), the attitudes and involvement of GPs are key factors in its success. GPs in England and elsewhere have been observed to report a high level of systematic screening in their practice but achieve very low rates of identification of both hazardous/harmful and dependent drinkers (Johansson et al., 2002; Aalto et al., 2003; Drummond et al., 2005; Holmqvist et al., 2008; Nygaard et al., 2010). They perceive preventive medicine as a high priority (McAvoy et al., 1999), which might be expected to result in more routine enquiry about alcohol and hence identification of more of the large proportion of patients drinking to excess (Kaner et al., 1999; Eccles et al., 2005; Royal College of General Practitioners, 2008). Yet this study suggests that GPs' enquiry about alcohol problems is increasingly limited and on a responsive or targeted basis. Given that most GPs report seeing 100 or more patients per week, levels of identification still appear low, or short of the 20% of primary care patients who may be misusing alcohol (Anderson, 1993). Attitude theories suggest various factors that might inhibit a positive attitude to treating alcohol problems from translating into the clinical behaviours of identification and intervention (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993). GPs may be personally in favour of preventive approaches but not perceive them as normative behaviour. Alternatively, GPs may not perceive themselves as being enabled to manage patients with alcohol-related harm. Previous application of the SAAPPQ shows that GPs are more likely to treat alcohol problems where they: feel supported in this work; have received more education on alcohol; and feel secure in, and committed to, that role (Anderson et al., 2003). However, GPs indicate in the current study that they may often be too busy to intervene for alcohol problems. Their rates of training have declined since 1999 to levels highlighted as a concern in 1985 (Anderson, 1985; Kaner et al., 1999).

It is encouraging that GPs seem to perceive fewer barriers to intervention compared with those in 1999 and that there is a clear trend towards more agreement on incentives. However, the uniformly low ratings of effectiveness for current alcohol policies indicate broader disenchantment with approaches to the problem at large. Many GPs felt that alternative policy measures were likely to make a more positive impact on heavy drinking, views that are consistent with the recommendations of a recent UK Government Health Committee report on alcohol (House of Commons Health Committee, 2010). In particular, evidence of effectiveness is strong for the regulation of physical availability and the use of taxation to help reduce excessive drinking (Anderson et al., 2009). Given the broad reach of these strategies, the evidence supporting their effectiveness and the relatively low expense of implementing them, the expected impact of these measures on public health is comparatively high. In contrast, the expected impact is low for school-based education (Anderson et al., 2009). Although the reach of educational programmes is high, the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these programmes is low (Babor et al., 2010).

Nevertheless, GPs' views on policy issues suggest that they regard primary care intervention as just one part of a broader co-ordinated approach to tackling alcohol problems. While training and interventions that build clinical confidence are often recommended to achieve the potential for screening in primary care, with effective strategies identified for this (Kaariainen et al., 2001; Anderson et al., 2004b; Geirsson et al., 2005; Berner et al., 2007; Tsai et al., 2010), such initiatives can themselves be subject to low uptake by GPs (Ruf et al., 2010). Recompensing practices by including SBI for alcohol in the national GP contract, either via the Quality and Outcomes Framework (the national reward and incentive scheme) or as a Direct Enhanced Service (a commissioned addition to core services), might boost uptake and screening activity. Pessimism about the way that broader alcohol strategy is tackling widespread alcohol problems in society may also influence clinical decisions about intervening with individual problem drinkers. One GP, for instance, commented on their questionnaire:

In the UK alcohol use is widespread and there needs to be a cultural sea change if we are ever going to control this epidemic. It is unlikely to happen as we are a weak society led by weak leaders and informed by the world's weakest media!

Research on attitudes of other primary care staff or practitioners towards intervening against excessive drinking would indicate what aspects of the broader environment may be perceived by GPs as more or less supportive. Our results suggest a need for translational work (Nilsen, 2010; Ruf et al., 2010) where researchers and practitioners work together on understanding the evidence-base supporting SBI and identifying the best means of incentivizing this important work and embedding it into everyday practice.

Funding

This work was supported by the Alcohol Education and Research Council (R 04/2008).

Conflict of interest statement. The research received ethics approval from the Sunderland NHS Research Ethics Committee (North East Strategic Health Authority). This manuscript conforms to the guidelines in the STROBE Statement (von Elm et al., 2007). Eileen Kaner chaired the National Institute for Clinical Excellence PDG on the prevention of alcohol-use disorders in adults and adolescents on which Nick Heather was a member. Paul Cassidy presented to a House of Commons Select Committee on alcohol. N.H. and E.K. are trustees of the Alcohol Education & Research Council, and Catherine Lock is a member of the grant advisory panel. Following funding, the AERC played no part in the collection of data or their interpretation, in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Alcohol and Alcoholism online.

REFERENCES

- Aalto M, Pekuri P, Seppä K. Obstacles to carrying out brief intervention for heavy drinkers in primary health care: a focus group study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:169–73. doi: 10.1080/09595230100100606. doi:10.1080/09595230100100606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. Managing alcohol problems in general practice. BMJ. 1985;290:1873–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6485.1873. doi:10.1136/bmj.290.6485.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. Effectiveness of general practice interventions for patients with harmful alcohol consumption. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:386–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. Alcohol and Primary Health Care. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Clement S. The AAPPQ Revisited: the measurement of general practitioners' attitudes to alcohol problems. Addiction. 1987;82:753–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01542.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kaner E, Wutzke S, et al. Attitudes and management of alcohol problems in general practice: Descriptive analysis based on findings of a World Health Organization international collaborative survey. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:597–601. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kaner E, Wutzke S, et al. Attitudes and managing alcohol problems in general practice: an interaction analysis based on findings from a WHO collaborative study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004a;39:351–6. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Laurant M, Kaner E, et al. Engaging general practitioners in the management of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption: results of a meta-analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2004b;65:191–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009;373:2234–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60744-3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berner MM, Harter M, Kriston L, et al. Detection and management of alcohol use disorders in German primary care influenced by non-clinical factors. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:308–16. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KEA, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179:245–52. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J, Dickinson H, Eccles M. Response rates in postal surveys of healthcare professionals between 1996 and 2005: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:160. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-160. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-9-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings SM, Savitz LA, Konrad TR. Reported response rates to mailed physician questionnaires. Health Serv Res. 2001;35:1347–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deehan A, Templeton L, Taylor C, et al. How do general practitioners manage alcohol-misusing patients? Results from a national survey of GPs in England and Wales. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1998a;17:259–66. doi: 10.1080/09595239800187091. doi:10.1080/09595239800187091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deehan A, Templeton L, Taylor C, et al. Low detection rates, negative attitudes and the failure to meet the ‘Health of the Nation’ alcohol targets: findings from a national survey of GPs in England and Wales. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1998b;17:249–58. doi: 10.1080/09595239800187081. doi:10.1080/09595239800187081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier. London: Department of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Safe. Sensible. Social. The Next Steps in the National Alcohol Strategy. London: Department of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond C, Oyefeso A, Phillips T, et al. Alcohol Needs Assessment Research Project (ANARP): the 2004 National Alcohol Needs Assessment for England. London: Department of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Chaiken S. The Psychology of Attitudes. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, et al. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007:MR000008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000008.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geirsson M, Bendtsen P, Spak F. Attitudes of Swedish general practitioners and nurses to working with lifestyle change, with special reference to alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:388–93. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Commission Audit Commission. Are We Choosing Health? The Impact of Policy on the Delivery of Health Improvement Programmes and Services. London: Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist M, Bendtsen P, Spak F, et al. Asking patients about their drinking: a national survey among primary health care physicians and nurses in Sweden. Addict Behav. 2008;33:301–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.021. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons Health Committee. Alcohol. Vol. 1. London: The Stationery Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson K, Bendtsen P, Akerlind I. Early intervention for problem drinkers: readiness to participate among general practitioners and nurses in Swedish primary health care. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:38–42. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaariainen J, Sillanaukee P, Poutanen P, et al. Opinions of alcohol-related issues among professionals in primary, occupational, and specialized health care. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36:141–6. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Haighton CA, McAvoy BR. ‘So much post, so busy with practice -so no time!': a telephone survey of general practitioners’ reasons for not participating in postal questionnaire surveys. BJGP. 1998;48:1067–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Heather N, McAvoy BR, et al. Intervention for excessive alcohol consumption in primary health care: attitudes and practices of English general practitioners. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:559–66. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Heather N, Brodie J, et al. Patient and practitioner characteristics predict brief alcohol intervention in primary care. BJGP. 2001;51:822–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner E, Dickinson H, Beyer F, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007:CD004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy BR, Kaner EF, Lock CA, et al. Our Healthier Nation: are general practitioners willing and able to deliver? A survey of attitudes to and involvement in health promotion and lifestyle counselling. BJGP. 1999;49:187–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Workforce Review Team. Workforce Summary—General Practitioners. London: Centre for Workforce Intelligence; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen PER. Brief alcohol intervention research and practice—towards a broader perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:964–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02779.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard P, Paschall MJ, Aasland OG, et al. Use and barriers to use of screening and brief interventions for alcohol problems among Norwegian general practitioners. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:207–12. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raistrick D, Heather N, Godfrey C. Review of the Effectiveness of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. London: National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse, Department of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M, et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for global burden of disease. Eur Addict Res. 2003;9:157–64. doi: 10.1159/000072222. doi:10.1159/000072222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of General Practitioners. Profile of UK General Practitioners. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of General Practitioners. What is General Practice. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ruf D, Berner M, Kriston L, et al. Cluster-randomized controlled trial of dissemination strategies of an online quality improvement programme for alcohol-related disorders. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:70–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS Statistics Base 17.0 User's Guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YF, Tsai MC, Lin YP, et al. Facilitators and barriers to intervening for problem alcohol use. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1459–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05299.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. doi:10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Gender, Health & Alcohol Use. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global Health Risks. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.