Abstract

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) commonly colonizes the upper respiratory tract of children and causes otitis media, sinusitis, and bronchitis. Invasive NTHi diseases such as meningitis and septicemia have rarely been reported, especially in children with underlying predisposing conditions such as head trauma and immune compromise. However, we report a previously healthy 2-year-old girl who developed meningitis and septicemia caused by NTHi biotype ΙΙΙ. She was treated with dexamethasone, meropenem, and ceftriaxone, and recovered uneventfully. We wish to emphasize that NTHi should be borne in mind as a potential pathogen that can cause meningitis and septicemia, even in previously healthy children.

Keywords: Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, Meningitis, Septicemia, Child

Introduction

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) is responsible for most cases of invasive H. influenzae disease, including meningitis and septicemia, in unvaccinated children. With the decline in the incidence of invasive Hib disease as a result of the Hib vaccine program, nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi) has become an important cause of invasive H. influenzae disease in vaccinated children [1].

NTHi is part of the normal flora in the upper respiratory tract of children and commonly causes local respiratory tract diseases, including otitis media, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, and bronchitis [2, 3]. Meningitis and septicemia have been reported rarely in children with underlying predisposing conditions, including head trauma [4], cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage [5], and immune compromise [6], in neonates associated with colonization of the maternal genital tract [7, 8], and more rarely in previously healthy children [9–11].

According to a Japanese nationwide surveillance system, the incidence of H. influenzae meningitis was 4.7 cases/100.000/year in 1994 [12]. The frequency with which NTHi meningitis in children occurs seems to vary, depending on the populations surveyed: 4 (0.7%) of the 535 patients with H. influenzae meningitis were NTHi strains [13]; 2 (4.9%) of the 41 pediatric patients with H. influenzae meningitis were NTHi strains [14].

We report a case of a previously healthy 2-year-old girl who developed meningitis and septicemia caused by NTHi biotype ΙΙΙ, and wish to emphasize that NTHi must be borne in mind as a potential pathogen that can cause invasive disease, even in previously healthy children.

Case report

On 7 September 2008 a previously healthy 2-year-old girl was admitted to the hospital with a 12-h history of fever and vomiting. She had no rhinorrhea or cough before her hospital stay. She had been born at 40 weeks of gestation, and her birth weight was 3062 g. Subsequent mental and physical development had been normal. She had no history of head trauma, CSF leakage, or immune compromise. She had been immunized with various vaccines as appropriate according to the immunization schedule for children (BCG, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, and varicella). She lived with her parents and 3-year-old brother, and attended a nursery school.

On admission, she had a body temperature of 39.2°C, heart rate of 122 beats/min, respiratory rate of 40/min, and an instant capillary refill time without cold peripheries. Consciousness was clear. Ear–nose–throat examination showed a red and swollen pharynx. No clinical findings of otitis media were observed. Examination of her chest and abdomen was unremarkable. No rashes, anterior fontanelle bulging or nuchal rigidity was observed. Laboratory data on admission were: white blood cell (WBC) count, 13400/μl (neutrophils 91%, monocytes 2%, lymphocytes 7%); serum aspartate aminotransferase (ALT), 29 IU/l; serum alanine aminotransferase (AST), 17 IU/l; serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 252 IU/l; serum C-reactive protein (CRP), 1.5 mg/dl. An abdominal X-ray showed no abnormalities. She was initially treated with intravenous fluid and antipyretics, with her condition monitored closely.

On the second day of admission, the vomiting persisted, and the patient complained of headache. She had a body temperature of 39.3°C, heart rate of 145 beats/min, and respiratory rate of 45/min. She became disoriented and the Glasgow coma scale showed an eye opening (E) score of 4, verbal response (V) score of 2, and best motor response (M) score of 5. Nuchal rigidity and Brudzinski’s sign were positive. No anterior fontanelle bulging or hemiparesis were observed, and Kernig’s sign and Babinski’s sign were negative. The laboratory data on September 8 were: WBC count, 15300/μl (neutrophils 82%, monocytes 9%, lymphocytes 8%); ALT, 30 IU/l; AST, 16 IU/l; LDH, 307 IU/l; fasting blood glucose, 144 mg/dl; CRP, 15.0 mg/dl; CSF cell count, 3146 cells/μl (polymorphonuclear leucocytes, 78%); CSF protein, 51 mg/dl; CSF glucose, 35 mg/dl. Gram staining of the CSF revealed the presence of small, Gram-negative, pleomorphic rods resembling H. influenzae. However, a CSF test kit designed to detect the capsular antigens of bacteria causing meningitis (Pastrorex Meningitis; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) gave a negative result for Hib antigen. On the basis of the clinical and laboratory findings, diagnosis of bacterial meningitis was made, and empiric treatment with ceftriaxone sodium hydrate (CTRX) (120 mg/kg/day, 12-hourly) and meropenem hydrate (MEPM) (140 mg/kg/day, 8-hourly) was started. To avoid neurological sequelae, dexamethasone (0.60 mg/kg/day, 6-hourly) was also administered for 2 days. The CSF culture was positive after incubation at 37°C for 2 days. Blood culture was positive after incubation at 35°C for 3 days. The isolates were subsequently identified as H. influenzae by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, followed by a basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) search in the laboratory of Ubukata Kimiko at the Kitasato Institute for Life Sciences Kitasato University. On serotyping [15], no agglutination was observed with antisera against the capsular serotypes a through f, leading to categorization of the strain as nontypeable. On biotyping [16], the organism failed to produce indole and to decarboxylate ornithine, but was able to hydrolyze urea, leading to its categorization as biotype ΙΙΙ. H. influenzae biotype ΙΙΙ could be distinguished from H. aegyptius by its fermentation of xylose or by its growth on tryptic soy agar containing X and V factors [17]. All of the CSF, blood, and throat swab cultures yielded beta-lactamase-negative NTHi biotype ΙΙΙ. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of several antibiotics for the organism are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration of several antibiotics for nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae biotype ΙΙΙ isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Ampicillin | 0.25 |

| Cefditoren | <0.03 |

| Cefcapene | <0.03 |

| Cefotaxime | <0.03 |

| Panipenem | 1 |

| Telithromycin | 8 |

| Clarithromycin | <0.03 |

| Meropenem | <0.03 |

| Ceftriaxone | <0.03 |

| Chloramphenicol | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | <0.5 |

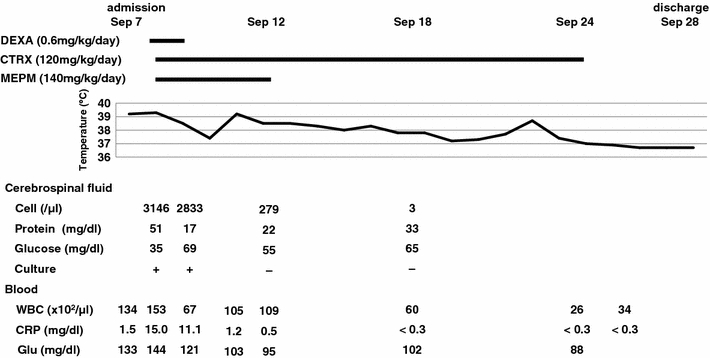

A repeat CSF culture on September 9 was also positive. Blood culture was not repeated. On September 12, the fever resolved and the signs of meningeal irritation were no longer positive. We discontinued MEPM on the basis of the result from antibiotic susceptibility testing. Repeat CSF cultures on September 12 and 18 were both negative. On September 24, CTRX was stopped when the serum CRP had remained within the normal range for 7 days. On September 28, she was discharged without any apparent neurological sequelae (Fig. 1). Because of the unusual finding of NTHi meningitis, further investigations were performed on the child. The results revealed normal levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgG subtypes, IgA, IgM, CD4, CD8, and of the blood complement components. Cranial and paranasal sinus computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the head were normal. HIV testing was not performed.

Fig. 1.

Clinical course of a 2-year-old girl with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae meningitis. DEXA dexamethasone, CTRX ceftriaxone, MEPM meropenem, WBC white blood cell, CRP C-reactive protein

Discussion

We report a rare case of meningitis and septicemia caused by NTHi biotype ΙΙΙ. This case demonstrates that NTHi should be borne in mind as a potential pathogen that can cause meningitis and septicemia, even in previously healthy children. Almost all cases of H. influenzae meningitis in unvaccinated children are caused by Hib or biotype Ι strains [16]. In contrast with Hib, NTHi is primarily recognized as a commensal organism in the upper respiratory tract [3]. However, NTHi biotype ΙΙΙ seems to have the potential to cause invasive disease such as meningitis [4, 9, 10] and septicemia [7, 9]. Therefore, children presenting with invasive NTHi disease should be promptly subjected to further evaluation and diagnostic imaging for identifying predisposing factors such as head trauma [4], CSF leakage [5], and immune compromise [6].

Concerning the possible route of transmission of NTHi biotype ΙΙΙ, it seems likely that the meningitis and septicemia in our patient were caused by the strain isolated from her throat culture, because all strains isolated from the CSF, blood, and throat belonged to identical biotypes and the MIC distributions were almost identical.

A subgroup of NTHi strains is spontaneous capsule-deficient progeny of Hib strains called b− strains. The b− strains might be generated by loss of their capsulation ability through homologous recombination. The frequency of b− strains in Hib is 0.1–0.3% [14, 18, 19]. The b− strains cannot be ruled out for our patient’s strain, because the slide agglutination test against the capsular serotypes are not able to differentiate between NTHi and b− strains.

Since the 1980s, when Hib conjugate vaccines were introduced in many foreign countries, the incidence of Hib meningitis has decreased dramatically. As a consequence, NTHi has become relatively more important as a pathogen for meningitis. In December 2008, Hib conjugate vaccine was introduced in Japan. Since the introduction of Hib conjugate vaccine, investigation of capsular serotypes is necessary in all cases of H. influenzae meningitis, because Hib vaccine does not protect against meningitis due to nontypeable strains. We conclude that NTHi biotype ΙΙΙ must be borne in mind as a potential pathogen that can cause meningitis and septicemia, even in previously healthy children.

References

- 1.Heath PT, Booy R, Azzopardi HJ, Slack MP, Fogarty J, Moloney AC, et al. Non-type b Haemophilus influenzae disease: clinical and epidemiologic characteristics in the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine era. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:300–305. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200103000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy TF, Faden H, Bakaletz LO, Kyd JM, Forsgren A, Campos J, et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae as a pathogen in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:43–48. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318184dba2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill JM, St. Geme JW, 3rd, Cutter D, Adderson EE, Anyanwu J, Jacobs RF, et al. Invasive disease due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae among children in Arkansas. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3064–3069. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3064-3069.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunze W, Müller L, Kilian M, Schuhmann MU, Baumann L, Handrick W. Recurrent posttraumatic meningitis due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: case report and review of the literature. Infection. 2008;36:74–77. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinello RA, Teitelbaum J, Young E, Hostetter MK. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in an eleven-year-old. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(281):285–286. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200403000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faden H. Meningitis caused by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in a four-month-old infant. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:254–255. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199103000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Retter ME, Bannatyne RM. Neonatal infection with Haemophilus influenzae biotype ΙΙΙ. Can Med Assoc J. 1980;123:717–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hershckowitz S, Elisha MB, Fleisher-Sheffer V, Barak M, Kudinsky R, Weintraub Z. A cluster of early neonatal sepsis and pneumonia caused by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:1061–1062. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143650.52692.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kay SE, Nack Z, Jenner BM. Meningitis and septicemia in a child caused by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae biotype ΙΙΙ. Med J Aust. 2001;175:484–485. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuthill SL, Farley MM, Donowitz LG. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:660–662. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199907000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nizet V, Colina KF, Almquist JR, Rubens CE, Smith AL. A virulent nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:180–186. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamiya H, Uehara S, Kato T, et al. Childhood bacterial meningitis in Japan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:S183–S185. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199809001-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasegawa K, Chiba N, Kobayashi R, et al. Nationwide Surveillance Study Group for Bacterial Meningitis. Molecular epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae strains isolated from patients with meningitis during 1999 to 2003. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2004;78:835–845. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.78.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishiwada N, Cao LD, Kohno Y. PCR-based capsular serotype determination of Haemophilus influenzae strains recovered from Japanese paediatric patients with invasive infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:895–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittman M. Variation and type specificity in bacterial species of Haemophilus influenzae. J Exp Med. 1931;53:471–492. doi: 10.1084/jem.53.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilian M. A taxonomic study of the genus Haemophilus with the proposal of a new species. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;93:9–62. doi: 10.1099/00221287-93-1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazloum HA, Kilian M, Mohamed ZM, Said MD. Differentiation of Haemophilus aegyptius and Haemophilus influenzae. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand B. 1982;90:109–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1982.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoiseth SK, Connelly CJ, Moxon ER. Genetics of spontaneous, high-frequency loss of b capsule expression in Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1985;49:389–395. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.389-395.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falla TJ, Dobson SR, Crook DW, et al. Population-based study of non-typable Haemophilus influenzae invasive disease in children and neonates. Lancet. 1993;341:851–854. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93059-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]