Abstract

This study seeks to explore the sources of strength giving rise to resilience among older people. Twenty-nine in-depth interviews were conducted with older people who receive long-term community care. The interviews were subjected to a thematic content analysis. The findings suggest that the main sources of strength identified among older people were constituted on three domains of analysis; the individual-, interactional and contextual domain. The individual domain refers to the qualities within older people and comprises of three sub-domains, namely beliefs about one’s competence, efforts to exert control and the capacity to analyse and understand ones situation. Within these subdomains a variety of sources of strength were found like pride about ones personality, acceptance and openness about ones vulnerability, the anticipation on future losses, mastery by practising skills, the acceptance of help and support, having a balanced vision on life, not adapting the role of a victim and carpe-diem. The interactional domain is defined as the way older people cooperate and interact with others to achieve their personal goals. Sources of strength on this domain were empowering (in)formal relationships and the power of giving. Lastly, the contextual domain refers to a broader political-societal level and includes sources of strength like the accessibility of care, the availability of material resources and social policy. The three domains were found to be inherently linked to each other. The results can be used for the development of positive, proactive interventions aimed at helping older people build on the positive aspects of their lives.

Keywords: Older people, Community, Resilience, Coping, Development

Introduction

Although old age is often accompanied by feelings of loss and other developmental stressors (Bartky 1999; Hardy et al. 2002), research shows that the majority of older people are capable to moderate the impact of these distresses on their day-to-day lives (Hardy et al. 2002, 2004). It has been demonstrated that subjective wellbeing does not diminish in later adulthood for a large majority of older people (Staudinger 2000; Henchoz et al. 2008). This raises the question as to how, in the face of major treats, older adults are able to keep their wellbeing buoyant.

Research demonstrates various psychological factors that buffer or absorb the impact of negative influences. One of these factors concerns personal qualities or personal attributes. For example, Kobasa et al. (1982) studied ‘hardy persons’ and concluded that they have at least three personality traits: commitment, control, and challenge. Antonovsky (1987) introduced the concept of ‘sense of coherence’ to provide an explanation for the role of stress in human functioning. Likewise Bandura (1977) found that self-efficacy beliefs (i.e. beliefs about one’s ability to manage prospective situations) mediate changes in behaviour and fear arousal. Nowadays, scholars increasingly acknowledge that positive adaption and development (resilience) is also influenced by external factors, like families, communities and wider contextual circumstances (Luthar et al. 2000; Masten 2001).

In their studies these authors among others showed that an optimistic view of ageing has a positive effect on subjective health and life satisfaction (Wurm et al. 2008) and that self, personality and life regulation safeguard life satisfaction in the face of somatic or socioeconomic risk (Staudinger et al. 1999). Besides these personal attributes, contextual factors such as cultural background also turn out to influence people’s reactions to stressful situations (Neimeyer 1997).

However, it is unclear to what extend the insights of these studies are applicable to older people living in the community and who are in need of long-term professional care. It is often assumed that sources of strength diminish with age, but it is relatively unknown what kinds of sources of strength are specifically associated with getting older.

Most research into resilience and sources of strength among older people is based on quantitative data. These studies showed that older people possess sources of strength that help them to buffer against adversity (see for example Staudinger et al. 1999; Wagnild 2008; Windle et al. 2008; Masten and Wright 2009). However, we need to increase our understanding of how older people themselves reason about the mediating sources of strength they perceive as crucial when encountering developmental threats. This study presents findings, using an in-depth, bottom up approach to explore the mediating sources of strength giving rise to resilience among older people living in the community who receive long-term care from the perspective of older people themselves.

Theory

To understand resilience and how resilience is related to the availability and use of sources of strength we first describe the theoretical background of this concept. Resilience is often defined as ‘patterns or processes of positive adaptation and development in the context of significant threats to an individual’s life or function’ (Masten and Wright 2009; compare Garmezy 1991; Luthar 2006). Research into resilience is rooted in positive psychology (Seligman and Csikszentmihaly 2000) and was originally developed in the domain of developmental psychology dealing with childhood and adolescence (Garmezy 1991; Werner and Smith 1982; Rutter 1987). Only recently has resilience been extended to other periods of the lifespan including old age (Ryff et al. 1998; Masten and Wright 2009).

Resilience research focuses on ways to improve wellbeing and stimulate health (Van Regenmortel 2009). A belief in the potency and strengths of people, even among the most vulnerable, is an important aspect of resilience. However, resilience is not a synonym for invulnerability (Werner and Smith 1982; Rutter 1993). People can be vulnerable and hurt even though they are able to manage challenging circumstances (Werner and Smith 1982; Van Regenmortel 2002).

Two co-existing concepts are central to resilience, i.e. first the presence of a significant (developmental) threat or risk to a given person’s wellbeing and, secondly, the evidence of a positive adaptation in this individual despite the adversity encountered (Fraser et al. 1999; Luthar et al. 2000; Van Regenmortel 2002).

On a conceptual level resilience is considered as the bridge between coping and development (Greve and Staudinger 2006; Leipold and Greve 2009). A developmental stressor can be recognised or masked by defensive mechanisms. If a certain risk or threat for ones life or function is perceived as stressful, different kind of (coping) processes are activated (see Brandtstädter and Rothermund 2002; Jopp and Schmitt 2010 for a further specification of these coping processes).

This mobilization of sources of strength in turn influence the extent to which the threat unfavourably affects further dimensions (e.g. subjective wellbeing and health) and one’s development. When there are no (further) serious deficits to be found in the subjective wellbeing and health one can speak of resilience (Leipold and Greve 2009).

Method

Design

This study used a naturalistic inquiry (Lincoln and Guba 1985). Naturalistic inquiry aims to understand the particularities of a phenomenon in its natural setting and from the perspective of those involved. In our study we explored the sources of strength giving rise to resilience among older people who receive long-term community care from the perspective of older people themselves. This article focuses on the experience of stressful events by older persons and the sources of strength they rely on. Ungar (2003) promoted qualitative methods to study resilience as these methods are well-suited to identify processes and patterns which lead to better accounts of the experiences of research participants. Moreover, qualitative methods are suitable to give voice to those who are otherwise silenced (in this study older people). We wanted to focus the perspective of the older people themselves as they, as expert through experience, know how to adjust themselves to growing older and the losses that comes with it.

Setting

The research was conducted in a medium-sized city in the Netherlands (103.000 inhabitants). People from six different kinds of neighborhoods were subject of this study. The socio-economic status of most of these inhabitants is relatively low. Thirty percent of the inhabitants are 55 or older and five percent are 80 or older. A healthcare centre run by various healthcare professionals and social workers is located in the hearth of the research area. The centre liaises with other health and social care organizations such as homecare, general practitioners, social work and intramural care in order to provide older people in the community with integrated services. For health and other reasons, the older people that participated in this research were in need of professional care from at least one of the above organizations. The level of professional care was determined through a standard assessment procedure carried out by government agency.

Data collection

Professionals of the health care centre as well as professionals from the allied organisations providing integrated care for older people in the community in the research area (n = 12) were asked to select a number of older people for in-depth interviews. The following selection criteria were used: (1) aged 55 or older (2) receiving long-term professional care from one care or social health organizations involved (3) being able to give informed consent and having a reasonable insight into their own infirmity (4) being able to speak the Dutch language and (5) being able to hold a conversation for at least 1 h. An important reason for selecting the respondents was maximum variety (versus statistical representation). We selected the respondents because of the variety in disability and diseases, a variety in stages of the disabilities and diseases and a variety in age and marital status. The prospective participants received a letter inviting them to take part in the study and setting out the aims and ethical considerations involved. A few days later they were given additional information by telephone. All participants agreed to participate except for one who was admitted to hospital during the research period. The interviews took place in the respondents’ own homes and lasted approximately 2 h (varying between 75 and 165 min).

The interviewer (first author) started the interview with the open question ‘Can you describe your current situation?’ Interview guidelines were used to explore the experiences and responses to their situation, the impact of their situation on their lives and family, the kind of support they received and the sources of strength they rely on. There was ample opportunity during the interview to discuss any issue that emerged from the conversation. Care was taken to prevent common pitfalls including outside interruptions and jumping from one subject to the other (Britten 1995).

Respondents

Thirty people were interviewed. One respondent turned out to be younger than 55 and was therefore excluded from the analysis. The remaining 29 participants ranged from 59 to 90 years of age (mean 78), and included 11 men and 18 women. Three of the respondents were younger than 70 (respectively 59, 63 and 64) years of age when the interview took place. Although they were relatively young, they were included in the research because they suffered diseases typically related to old age (i.e. Alzheimer’s disease, severe diabetes, hearth and lung failure and muscular deterioration). Moreover all three respondents received care from professionals specialized in care for older people; two of them received care from a certified professional consultant on ageing and the other respondent from a case manager supporting people diagnosed with dementia and their family. Twenty-four participants lived in their own homes, four lived in sheltered accommodation and one had recently moved to a residential home. Eighteen respondents lived alone and the other 11 lived with their spouse or another housemate. Seven respondents were married, 11 widowed and the remaining respondents were either divorced or were never married. All respondents had experienced some kind of loss or difficult changes as a result of the normal ageing process, as well as some kind of chronic disease and functional decline. Significant loss included the illness and/or death of loved ones, physical and/or psychological frailty, or their own divorce or their children’s divorce. The intensity of the professional care varied between help with daily activities (taking a shower, getting dressed) to diabetes checks that in general take place four times a year.

Analysis

With the consent of all the respondents the interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and subjected to a thematic content analysis (Miles and Huberman 1994). We used previous literature on resilience and sources of strength to inform our qualitative study. This overview was intended to access a broad range of information about sources of strength to encounter developmental stressors in all stages of life and was developed and expanded during our fieldwork.

The literature functioned as ‘sensitizing concepts’, which gave the first author a general sense of reference and guidance in approaching the empirical data. Whereas definite concepts provide prescriptors of what to see, sensitizing concepts merely suggest directions in which to look (Blumer 1969). Sensitizing concepts were chosen to steer the analysis, but only loosely. They do not have a full operational definition, and leave room for the researcher to find out how the concept manifests itself in the data (Schwandt 2001).

The computer software for qualitative data analysis Atlas Ti 5.2 for Windows was used to facilitate the sorting of the interviews and the quotations. Each interview transcript was read line-by-line by the first author, and labelled (interview sentences were given a label) with previous literature on resilience in mind. The author team discussed the content description of the codes and their labels. During this iterative process, categories and domains emerged in which sources of strength occurred. Sometimes labels were changed to better express the meaning of the data. For instance, in the interactional domain ‘contact among older people’ was redefined as ‘the power of giving,’ as this better illuminated the meaning of what was communicated. Jointly exemplars of interview quotes were identified to illustrate each code/source of strength.

Quality procedures

We used ‘member check’ as one of the essential procedures to assess the validity of our study (Meadows and Morse 2001; Kuper et al. 2008). In our study 15 interviewees agreed to receive an extensive summary of their transcript by post. In an accompanying letter they were asked whether they recognised the summary, whether it expressed what they had wanted to express and to respond to the researcher if this was not the case (a stamped addressed envelope was included). None of the respondent disagreed with the content of the transcript. The other 14 respondents who indicated they did not want to receive the summary were asked whether they agreed with (anonymous) publication of all they had said during the interview without seeing the summary. All 14 respondents agreed orally after having finished the interview. In qualitative research the process of data collection and analysis ends when ‘saturation’ is reached (Meadows and Morse 2001). This is the point where no information is added and replication of data occurs. The point of saturation cannot be predicted in advance and is dependent on the scope of the study, the quality of the interviews and the appropriateness of participant selection. In this study saturation was reached after 29 interviews. The second and third authors were not engaged in the data collection process, and did not have contact with the respondents. This made it possible for them to keep a professional distance while analysing the data. In order to guarantee the external validity of this study the readers are enabled to assess the potential transferability of its results to other settings because a ‘thick description’ of the studied context and meanings expressed by participants is presented in this article.

Ethics

Informed consent was gained before starting the interviews. Removing the names and other characteristics from the transcripts ensured anonymity of the respondents. Moreover, the transcripts were not shared with others and after the study the transcripts and tapes were destroyed. The interviewer had no (therapeutic) relationship with the respondents.

Results

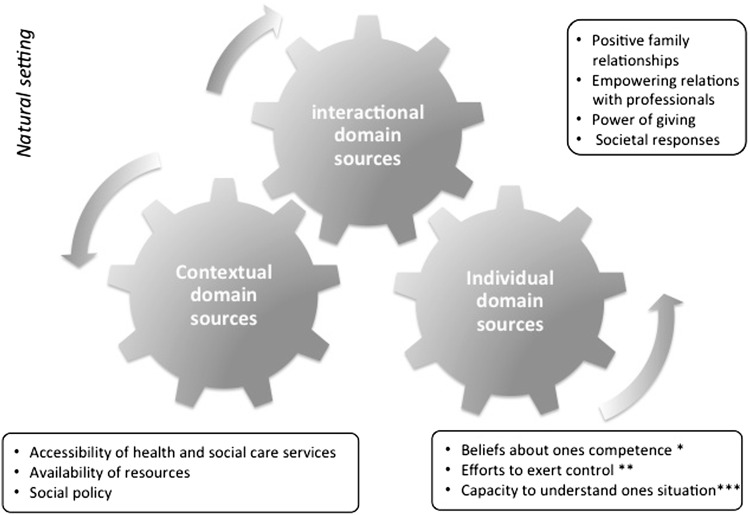

The results of the study suggest that all respondents used a combination of different sources of strength to adapt to their declining health, revealing a variety of individual approaches. Despite this variety, three domains in which sources of strengths occurred were found in the data; the individual-, interactional- and contextual domain. The individual domain refers to the qualities and sources of strength within older people. This domain comprised of three sub-domains, namely beliefs about one’s competence, efforts to exert control and the capability to analyse and understand one’s situation. Within these sub-domains different sources of strength were found in the data; the beliefs about one’s competence included the sources of strength labelled pride about ones own personality and acceptance and openness about ones vulnerability. The sources of strength that were revealed in the data within the sub-domain efforts to exert control were: anticipating on future losses, mastery by practicing skills and the acceptance of help and support. Lastly the capability to analyse and understand one’s situation turned out to include the sources of strength balanced view on life, not adapting the role of a victim and carpe diem.

The interactional domain can be described as the way older people living in the community interact with significant others like their relatives and friends, neighbours and professionals. This domain refers to the way older people cooperate with others to achieve their goals and to endow meaning to their lives as well as to the efforts from the social community to generate individual domain sources of strength within older people. Interactional domain sources that were found in the data contained positive family relations, empowering relationships with professionals, the power of giving and societal responses.

Lastly, the contextual domain refers to a broader political-societal level including the efforts on this domain to deter community treats, improve quality of life and facilitate citizen participation. The sources of strength that were revealed in the data include the accessibility of health and social care services, the availability of social as well as material resources and the effects of social policy on older people living in the community.

Furthermore, the three domains were found to be inherently linked to each other. We will describe our results, using these domains and present subdomains within each of the domains. Our key findings are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Sources of strength giving rise to resilience. *Beliefs about one’s competence include the sources of strength labelled pride about ones own personality and achievements and openness about ones vulnerability. **Efforts to exert control include the sources of strength labelled anticipating on future losses, mastery by practicing skills and the acceptance of help and support. ***Capacity to understand ones situation include the sources of strength labelled balanced view on life, not adapting the role of a victim and carpe diem

Individual domain sources

Beliefs about ones competence

Pride about ones personality The majority of the respondents presented themselves as being proud about their personality. For example, one of the female respondents said that she was fortunate to have an easy-going character. She explained that this personal attribute enabled her not to become embittered or hard as a result of her health decline and accompanying increased ADL-dependence. Furthermore she indicated her character allowed her not to blame others like her children and professionals for her situation. Others described themselves as ‘down to earth’, ‘level headed’ or ‘hospitable’. They explained that these personal attributes helped them to deal with their chronicle condition and in putting their own situation into perspective.

Acceptance and openness of ones vulnerability The acceptance of the limitations turned out to be an important source of strength contributing to adjusting to adversity. However, a number of respondents indicated how difficult it was to achieve this and that this was something that had taken time to come to terms with the infirmities of old age. Some respondents still struggled with being open about their feelings of insecurity and their doubts as they were used to conceal a lot to others. Although, they new it wasn’t always possible they wanted to deal with stressful situations on their own.

Some of the respondents who indicated that they accepted their vulnerability said this made it possible for them not to be too susceptive to others’ possible negative views of their limitations. One 75-year-old male with memory impairment indicated that ‘he couldn’t get a pill for his disease’ and that ‘it was inoperable’. He therefore did not see why he should be ashamed of his limitations as he was still the same person he was as before is health declined. He said that this belief made it easier for him to be open about it towards others and accept support from them.

Efforts to exert control

Anticipating on future losses Another commonly used source of strength for the respondents to manage stressful situations was to take action to actively influence outcomes of their situation.

Respondents for example described how they anticipated on losses that ‘may come along’. They took action to prevent impulsive actions at the time when, in their eyes, it is too late to make a proper choice. Moving within ordinary housing in order to remain in their own home as long as possible was a way to anticipate on future losses that was frequently mentioned by respondents. Relocation allowed the respondents to live close by shops and/or family and in a dwelling in which they could live with their (worsening) functional disability for a longer period of time. Others, in particular the respondents living alone, anticipated on their future losses by making appointments with their neighbours or children to keep an eye on them.

Mastery by practising skills Moreover, many respondents mentioned they maintained mastery over their situation by practising their skills. Some older people were determined and motivated to stay active in order to maintain their current state of health as long as possible. They said that by continuing practicing their knowledge and skills, they were more satisfied and felt they were able to influence their situation with their behaviour. One of the respondents (a 73-year-old male) indicated that, although the sessions with his professionals came to an end a long time ago, he still persevered in doing the exercises he learned from them. He said that he had found a way to integrate these exercises in his mourning ritual. This made it easier for him to persevere for such a long period of time. Although many other respondents described similar motivations to practice their skills, a few of them indicated they needed, but lacked, support from others to stimulate them to practice and improve their skills. Besides lack of support, some respondents indicated that the day care programme they followed did not always correspond with their skills, knowledge and expectations.

The day-care programme is not obliged, but they say it is useful. I have doubts about that. We start with drinking coffee, than one group starts reading the newspaper and another group with handicraft. I can read a newspaper by myself. And handicraft is something they do in jail as well. (Resp. 17, male, 79)

Acceptance of help and support Another effort respondents made to influence their situation was to accept the use of medical devices and other forms of support. For the majority of the respondents, however, this was not an easy task. Receiving care from others as well as using medical devices was something none of the respondents were used to. It took time for most of them to get used of that idea because they indicated that it confronted them with their deteriorating health and the perceived negative responses of their environment. Some of the respondents for example remembered the first time they had to use a wheelchair or walker very well.

You need to give up things piece by piece, for example with the wheelchair. At first I didn’t want to have anything to do with it. (…) I hated that thing in my house. (…) It’s such a step. A wheelchair indicates you are disabled. (Rep. 8, Female, 80).

However, a number of them eventually crossed barriers and were able to downplay their resistance for these devices and were able to change their perception about these devices. They said that, having crossed that barrier allowed them to see the advantages of such devices like staying active, experiencing less mobility problems and encountering more patience and understanding of others when for example crossing a road takes time.

I sometimes hear other older people say they don’t want to use a walking stick or a walker. It’s not a problem for me. Everybody can see if you’re wobbling when you walk. So I don’t care. (Resp. 29, Female, 75).

Capability to analyze and understand one’s situation

Balanced view on life Finding ways to analyse and understand one’s situation was another commonly cited source of strength for respondents to maintain their wellbeing. Some respondents were able to take a balanced view of their life. Looking back on their past, they referred both to moments of joy and to negative events. The majority of the respondents narrated with proud about their achievements in their work like being valued by their clients/customers or colleagues, their hobby’s or the way they had raised their children and what had become of them. In general, they looked back on these achievements with satisfaction. Illness and care for their partner, divorce of their children, the death of their partner or of their child(ren) and their own increased functional limitations were frequently mentioned negative life events.

Some of the respondents described how a balanced vision helped them to put negative things into perspective:

I’ve had a good life with all its ups and downs. I always say ‘I’m a rich person, but without money.’ (Resp. 28, Female, 90).

Not adapting the role of a victim All respondents suffered injuries, but a number of them emphasized that their disability was not the cornerstone of their identity and refused to feel powerless and had not adopted the role of a victim. They indicated they have always treated the adversity in their lives light heartedly and talked in terms of the things they were still able to do rather than focus on their problems. The fact that a number of respondents indicated at the start of the interview that “they had nothing special occurring in their lives” even though they faced serious illnesses and functional limitation is an expression of the way they perceived their situation.

Carpe diem Almost all respondents said it was difficult for them to describe their (long-term) future, because as one of them said: ‘I want to live one day at a time’. Their increased functional limitations sometimes forced them to focus on life her and now. In spite of this, the respondents were able to enjoy their lives in the face of serious illnesses. Their enjoyment and carpe diem-philosophy were mostly situated in brief moments of happiness like going away for a weekend, enjoying the visits of (grand)children or listening to music.

Interactional domain sources

Positive family relations

The way older people living in the community interact and communicate with others was another domain in which sources of strength were revealed. Although, many respondents expressed the wish to be as independent as possible they realised they needed support and said they really appreciated the help of others. However, the acceptance of this informal help created mixed feelings. On the one hand, almost all respondents revealed they were hesitative to ask too much support from others because they did not want to burden them too much. In most situations respondents indicated that their children were the one they first turned to. However, a general standpoint of the respondents was that they did not want to burden their children too much. On the other hand, they indicated they were happy they didn’t have to do everything on their own and therefore reduced their perceived level of stress. The supportive relationships were found to help the respondents to make sense of their situation in a different and less stressful manner. Respondents indicated they received both emotional and practical support from their relatives, but could also have a laugh with them and get involved in enjoyable activities, like daytrips or going out shopping. These positive social relationships seemed to contribute to their feelings of agency as this made them experience they were a part of a greater whole and meaningful to others.

I only have to whistle and he (great grandchild) knows it is me. I put him next to me on the table, because I can’t hold him on my arms. He kicks his legs and smiles at me. (Resp. 6, Male, 80)

The respondents mostly referred to their children and their offspring when they described examples of these warm relationships, but other family members and neighbours where also referred to as important persons in their lives.

Empowering relationships with professionals

Besides informal relationships the quality of the relationship with care professionals also affected the wellbeing of a lot of the respondents. Commitment, reliability and interest for example were frequently mentioned as positive aspects in relationship with their care professionals.

She (nurse practitioner) is really interested in us. She doesn’t have to look up in her administration why she has to visit us. (…) If I have a question she can’t answer she just asks the general practitioner later on. (…) It feels as though she’s been visiting us for years. She knows all about our family and everything. (Resp. 14, male, 85)

This statement revealed that, respondents do not expect from a professional they know everything immediately, as long as they show severe interest, listens carefully and do their utmost to find the information needed as soon as possible.

The power of giving

Some respondents described how, despite their limitations, they were still actively looking for ways to be meaningful to others. Mutual responsibility and solidarity turned out to be important values for the respondents. This power of giving is expressed by respondents in their wish to provide practical help to others. An example of this help given by respondents was exchanging keys with other older people living nearby to keep an eye on each other. Besides that, many examples were given of moral support.

I have a friend who just lost her husband. She’s having a bad time at the moment. I said to her: ‘Come on and cry.’ (…) I know how she feels and I can imagine she’s having a hard time. (Resp. 29, Female, 75)

For example, a number of the respondents had lost their spouse. This experience turned out better enable them to be empathic and supportive to others experiencing grief, which made them aware of the fact that although they (sometimes) were in need of help and support themselves this did not prevent them from being attentive towards others.

Societal responses

Societal responses were mentioned by some of the respondents as an issue of importance when it concerned their wellbeing and feelings of safety. Although, some of the respondents said they felt others were too busy with their work and their family to pay attention to them. They experienced they were no full members of society anymore from the moment they ended their active working career, a number of them indicated they were positively surprised by the way society responded to them. They said they experienced a tolerance for older people in society.

I thought no one would show an interest in you when you’re old and alone. But I’ve found that people are very kind, generous and helpful to me. (Resp. 26, Female, 81).

Contextual domain sources

Accessibility of health and social services

Respondents indicated they received the health and social services they needed. In some situations older people indicated professionals did their utmost to let them access the health and social services the wanted to have. For example one of the female (70 years) chronically ill respondents indicated a sheltered form of living looked like a good option for her. Together with her caregiver she worked on an application. Her care provider proposed to exaggerate her condition a bit, so that accessibility of that type of care was ensured.

Availability of social and material resources

A number of the respondents indicated they felt the need for specific support in order to achieve their personal goals. This need varied between the respondents. Whereas some respondents wanted to become a member of a mutual self help group to get in contact with fellow-sufferers, other respondents with a similar disease explained they did not want to talk too much about their feelings, but decided to cope with their disease by practicing their skills under professional guidance.

Social policy

In some cases respondents did not always have access to the sources they needed to optimize their wellbeing and therefore did not experience a developmentally enhancing environment. In some of the situations of the respondents for example, care policy prohibited access to contextual sources of strength:

Because of my old age and health, I would like to be monitored: I want intelligent people (i.e. care professionals) around me if something happens to me. So I wanted to move to sheltered accommodation but I didn’t get permission. My situation wasn’t severe enough. They (the governmental agency performing the assessment procedure) are very strict you know. (Resp. 18, Female, 81)

This female, like some other respondents indicated that the fact that she is not allowed to live in a sheltered home forces her to remain in her apartment that prohibits her going outdoors, this increases her feelings of loneliness, boredom and low level of self esteem.

However, other respondents gave examples of policy measures that enabled them to continue performing activities they otherwise were not able to do anymore like free access to the library including the delivery of the books at home.

Interaction between the domains

The extent in which a coping episode results in stability or change is found in this study to be affected by the combination of available and mobilized sources on both the individual, interactional as well as the contextual domain of analysis. The three domains are represented here as three gearwheels that need to interact favorably in order to create an optimal climate for development (i.e. resilience) to occur. For example, openness about ones vulnerability (individual domain) is closely linked to the interaction of older people with their social environment (interactional domain) and for example with the availability of health and social care that meet the needs of an individual older person (contextual domain). One man 75-year-old man explained he was happy with the way his care professional was approaching him and he was therefore willing to discuss his concerns with her. The acceptance of her support eventually led to more support like his participation in available day activities. These services he then participated in turn out to meet his needs and work out positively for his development process and, like he said, his ‘intensive and difficult task to get himself on his feet again after an operation’. The interaction between the individual, interactional and contextual domains have contributed to him downplaying the situation he perceived as stressful. Despite his speech impediment he now participates again in society, and develops his creative skills.

Discussion

Adjusting oneself to growing older and the loss that comes with it is a complex process. The findings of this study suggest that although older people often experience stressful life events, they possess and mobilize different sources of strength that help them to adapt constructively to developmental stressors. Sources of strength are not only found in the individual domain, but also on the interactional- as well as the contextual domain. Examples of sources of strength that were revealed were the positive beliefs older persons have about their competence, the efforts they make to exert control over their situation, their capacity to understand their situation, the positive and empowering social formal as well as informal interactions they have with others, the accessibility of health and social care service, the availability of material resources such as medical devices and the presence of an enabling context like a supportive social policy.

It should be borne in mind that we do not claim that our findings are representative of a universal process of adaptation to ageing; the results are based on a small sample and represented older people living in the community willing to participate in a research. Qualitative research does, however, never pretend that it can be generalized to a population. The findings are context-bound and the descriptions should reveal in which context the findings were retrieved. Readers may translate these findings to another than the studied context (Lincoln and Guba 1985).

The study builds on a growing body of research that suggest that resilience, leading to positive adaptation to adversity, can occur in all different stages of life including old age (see for example Ryff et al. 1998; Masten and Wright 2009).

In previous studies on resilience in different stages of life, positive adaptation to adversity was related to the mobilization of different sources of strength like self efficacy (Bandura 1977), commitment, control, challenge (Kobasa et al. 1982), and positive support (Henry 1999). More recently, studies mostly based on quantitative data confirmed this relationship specifically for older people as well (Wagnild and Young 1993; Wagnild 2008; Windle et al. 2008). We used this literature to inform our qualitative study as it provided insight into broad range of information about sources of strength to leading to positive adaptation to stressful situations. This study extends this knowledge by giving an in-depth picture of how older people living in the community in need of long-term professional care reason about these relationships and specifies these sources of strength found in all stages of life to the sources of strength that are specifically used among older people.

A number of issues that older people in this study had reported have been found through previous research on resilience throughout lifespan as well. However, through qualitative depth, our study adds further specifications of these sources from the perspective of older persons receiving long-term community care. For example “carpe diem” and “anticipating on future losses” can be seen as specifications of sources in the literature described as ‘experience of time’ (Staudinger et al. 1999) and ‘self regulation skills’ (Masten and Wright 2009). Likewise, “mastery by practicing skills” can be considered a further specification of mastery (Masten and Wright 2009) with emphasis on a persistent practising of skills (Vanistendael 2001) as the motor for mastery. Furthermore the warm, empowering relationships (Wolin and Wolin 1993; Wolff 1995; Nakashima and Canda 2005) were also found, but for older people these relationships were mostly described by the respondents with their children and their offspring and with care professionals. Lastly, we found “societal responses” as a source of strength that emphasizes the importance of positive images and societal responses to long-term disability in general and old age in particular.

Previous studies suggest that resilience can be regarded as a conceptual bridge between development and coping (Leipold and Greve 2009). The researchers state that coping strategies are important mechanisms that, when used effectively result in the stabilization of ones situation or in development or growth. Indeed, the older people who participated in this research emphasized that they used coping strategies like not adapting the role of a victim or anticipating on future losses that helped them stabilizing or improving their situation. However, in this study participants began to reveal that their way of coping could be enabled (or not) by empowering (formal as well as informal) social relationships and more structural (contextual) factors. Hence, it is suggested that efforts of the social environment around older people living in the community to stimulate their resilience and an enabling environment in which factors like a social policy and the availability of care that is focused on deterring community treats, improving quality of life and facilitating participation also determine the resilience of older people living in the community. In other words, mediating mechanisms giving rise to resilience not only include coping strategies, but also other kinds of sources of strength older people living in the community can rely on while responding to stressful situations such as empowering relationships and structural contextual factors like social policy and the availability of suitable care and support.

Turning to methodological issues, in our research we strived for a maximum of variety and therefore included older persons in our research from different age groups, with different diseases and different stages of the diseases. Other research, however, found that cultural background also influenced resilience (Neimeyer 1997). Unfortunately we were not able to include older people from different ethnical and cultural backgrounds in our research. All our respondents were white, older people with the Dutch nationality and background. In order to investigate the influence of ethnical and cultural diversity on resilience further work involving interviews with older people with different backgrounds is needed.

Another aspect that our research adds to the knowledge of resilience in old age is the suggestion of the process character of resilience. These processes seem to be going on in the lives of older people in need of long-term professional care for a long time, being more or less present and integrated in their daily lives. The results of our study for example show that accepting help from significant others or using medical devices is not easily dealt with. Crossing these barriers turned out to take time. However, our study does not identify developmental changes in the experiences of older people over time. For the future, examining data collected at different times would yield more detailed insights into how the experiences of older people living in the community change, and might identify possible shifts in the way they cope and the mediating sources of strength they rely on.

Our research suggests a connectedness between the three domains of analyses. Previous research on resilience also refers to the importance of contextual factors (for example Luthar et al. 2000; Masten 2001). However, not much is written about how individual, interactional and contextual factors influence each other and how they are linked to each other. Further research is suggested to establish the certainness of how exactly the three domains interact through longitudinal, qualitative studies using narrative analysis. Narrative analysis makes it possible to look more closely for differences in resilience and use of sources of strength between older people living in the community and retrospectively look at variations in mobilization of sources of strength within a person.

A limitation of our study is that we only included older people. In order to gain more insight into the interactional and the contextual domain other stakeholders should be included in the analysis as well. We therefore recommend that future work should include interviews with professionals as well as relatives of older people living in the community and policymakers to more fully understand the meaningfulness of social interactions as well as any other factor stimulating resilience.

Whereas the minority of the respondents experienced old age negatively and primarily referred to the negative consequences of ageing for their daily lives, the results suggest that the majority of the respondents describe their current situation as satisfying. Initially, a number of respondents felt ‘they had nothing special occurring in their lives to narrate about’. They indicated they ‘might not complain’ about their current situation. However, during the interviews they became more open and willing to articulate about stressful situations happening in their lives and about the way they perceived and handled these situations. A number of important issues concerning resilience were then encountered. This shows the importance of listening and probing as important skills of the interviewer (Kvale 1996). Moreover the results of this study confirm, like Masten (2001) already stated, how responding to adversity is regarded by the respondents as “ordinary magic” and has become a part of their lives.

The results of this study can be used to develop positive, pro-active, interventions promoting positive developmental outcomes in old age. As our findings reveal that resilience is situated on three inherently connected domains advice can be given to both older people and their family as well as to care professionals and policy makers.

Older people are recommended to open up the discussion about their wishes and expectations much earlier with their family and professionals. They should become aware that accepting help and support as well as medical devices allows them in most of the situations to remain in their own home.

The findings of our study show that responding and adapting to adversity takes time. For example, accepting ones vulnerability or accepting the use of medical devices is not something that the majority of the older people easily deal with. Often, a period of having doubts, being insecure and considering ones options precedes such a more or less stable situation. Professionals as well as those around older people should be aware of such stages in the resilience process while providing care and support and give space to the feelings of older people that accompany it.

Another point of attention for care professionals is the importance of their professional attitude. Professionals should be aware of how their attitude towards older people influences the care process. If for example an older person perceives the acceptance of care and support as a deterioration of their self-image professionals should wonder how to interact with these older people both verbally and non verbally in order to provide support without ignoring these feelings. Another recommendation to health professionals is to take the sources of strength individual older people possess and mobilize into account. These sources of strength can provide intervention targets for promoting resilience in older people, aimed at helping these people build on the positive aspects of their lives. Some positive results with the integration of ways of coping of older people in care interventions in the broad sense have already been found (Jonker et al. 2009). How professionals can be supported to identify these sources of strength and integrate (use) them in the care they provide to older people living in the community deserves further investigation.

Policy makers could gain insights from our study to increase their awareness of the importance of contextual factors. Their policy should be aimed at creating a so called enabling niche (Kal 2001) for older people in the community, allowing them to maintain in control of their situation as long as possible and remove environmental barriers that prohibit older people to reveal resilience.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Handling Editor: H.-W. Wahl.

References

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartky SL. Unplanned obsolescence: some reflections on aging. In: Walker MU, editor. Mother time. Woman, aging and ethics. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H (1969) Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. University of California Press, Berkeley

- Brandtstädter J, Rothermund K. The life course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: a two process framework. Dev Rev. 2002;22:117–150. doi: 10.1006/drev.2001.0539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Britten N. Qualitative research: qualitative interviews in medical research. Br Med J. 1995;311:251–253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser MW, Richman JM, Galinsky MJ. Risk, production and resilience: toward a conceptual framework for social work practice. Social Work Res. 1999;23(3):131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Resilience and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. Am Behav Sci. 1991;34:416–430. doi: 10.1177/0002764291034004003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greve B, Staudinger UM. Resilience in later adulthood and old age. Resources and potentials for successful aging. In: Cichetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental psychopathology, vol. 2. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 796–840. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S, Concato J, Gill TM. Stressful life events among community-living older persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:841–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S, Concato J, Gill TM. Resilience of community dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henchoz K, Cavalli S, Girardin M. Health perception and health status in advanced old age: a paradox of association. J Aging Stud. 2008;22:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DL (1999) Resilience in maltreated children: implications for special needs adoption. Child Welf Leag Am 519–540 [PubMed]

- Jonker AGC, Comijs HC, Knipscheer KCPM, Deeg DJH. Promotion of self-management in vulnerable older people: a narrative literature review of outcomes of the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) Eur J Ageing. 2009;6:303–314. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0131-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopp DS, Schmitt M. Dealing with negative life events: differential effects of personal resources, coping strategies and control beliefs. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7:167–180. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kal D (2001) Kwartiermaken: werken aan ruimte voor mensen met een psychiatrische achtergrond (Quarter-making: working on hospitality in the society for people with a psychiatric background). Amsterdam/Baarn, Boom

- Kobasa SC, Maddi SR, Kahn S. Hardiness and health: a prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982;42:168–177. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper A, Lingard L, Levinson W. Critically appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337:a1035. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S. InterViews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Leipold B, Greve W. Resilience. A conceptual bridge between coping and development. Eur Psychol. 2009;14(1):40–50. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newburg Park: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar (2006) Resilience in development. A synthesis of research across five decades. In: Chichette D, Cohen D (eds) Developmental psychopathology, 2nd edn, vol 2. Wiley, New York, pp 739–795

- Luthar SS, Cicchett D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Wright MO. Resilience over the lifespan: development perspectives on resistance, recovery, and transformation. In: Reich JW, editor. Handbook of adult resilience. New York: Guilford Publications; 2009. pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows LM, Morse JM. Constructing evidence within a qualitative project. In: Morse JM, Swanson JM, Kuzel AJ, editors. The nature of qualitative evidence. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis, an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima M, Canda E. Positive dying and resiliency in later life: a qualitative study. J Aging Stud. 2005;19:109–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2004.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer R. Meaning construction and the experience of chronic loss. In: Doka KJ, Davidson J, editors. Living with grief: when illness is prolonged. Philedelphia: Tayer and Francis; 1997. pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatr. 1987;57(3):316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience: some conceptual considerations. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14(8):626–631. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(93)90196-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B, Love GD. Resilience in adulthood and later life: defining features and dynamic processes. In: Lomranz J, editor. Handbook of aging and mental health: an integrative approach. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt TA. Dictionary of qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M, Csikszentmihaly M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger UM. Viele grunde sprechen dagegen und trotzdem fuhlen viele Menschen sich wohl: das paradox des subjectiven wohlbevindens [Many reasons speak against it but many people are happy: the wellbeing paradox] Psychol Rundsch. 2000;51:357–366. doi: 10.1026//0033-3042.51.4.185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger UM, Freund AM, Linden M, Maas I. Self, personality and life regulation: facets of psychological resilience in old age. In: Baltes PB, Mayer KU, editors. The Berlin aging study: aging from 70 to 100. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 302–328. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. Qualitative contributions to resilience research. Qual Soc Work. 2003;2(1):85–101. doi: 10.1177/1473325003002001123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Regenmortel T (2002) Empowerment en maatzorg. Een krachtgerichte, psychologische kijk op armoede. (Empowerment and tailored care. A strength based psychological approach to poverty). Acco, Leuven

- Van Regenmortel T. Empowerment als uitdagend kader voor sociale inclusie en moderne zorg. (Empowerment as a challenging framework for social inclusion and modern care) J Soc Interv Theory Pract. 2009;18(4):22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vanistendael S (2001) Veerkracht of de hoop van het realisme. (Resilience or the hope of realism). BICE, DKSR Breda, Geneve

- Wagnild G (2008) Resilience Scale-Nederlandse versie. Harcourt Test Publishers, Amsterdam

- Wagnild G, Young HM. The development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993;1(2):165–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, Smith RS. Vulnerable but invincible: a longitudinal study of resilient children and youth. New York: London McGraw-Hill; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Windle G, Markland DA, Woods RT. Examination of a theoretical model of psychological resilience in older age. Aging Mental Health. 2008;12(3):285–292. doi: 10.1080/13607860802120763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S. The concept of resilience. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatr. 1995;29:565–574. doi: 10.3109/00048679509064968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin SJ, Wolin S. The resilient self. How survivors of troubled families rise above adversity. New York: Villard; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wurm S, Tomasik MJ, Tesch-Römer C. Serious health events and their impact on changes in subjective health and life satisfaction: the role of age and positive view on ageing. Eur J Ageing. 2008;2(5):117–127. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0077-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]