Abstract

Background

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is an important cause of genital ulcers and can increase HIV-1 transmission risk. Our objective was to determine the incidence and correlates of HSV-2 infection in HIV-1-seronegative Kenyan men reporting high-risk sexual behavior, compared to high-risk HIV-1-seronegative women in the same community.

Methods

Cohort participants were screened for prevalent HIV-1 infection. HIV-1-uninfected participants had regularly scheduled follow-up visits, with HIV counseling and testing and collection of demographic and behavioral data. Archived blood samples were tested for HSV-2.

Results

HSV-2 prevalence was 22.0% in men and 50.8% in women (p<0.001). HSV-2 incidence in men was 9.0 per 100 person-years, and was associated with incident HIV-1 infection (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] 3.9, 95% CI 1.3–12.4). Use of soap for genital washing was protective (aIRR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.8). Receptive anal intercourse had a borderline association with HSV-2 acquisition in men (aIRR 2.0, 95% CI 1.0–4.1, p=0.057), and weakened the association with incident HIV-1. Among women, HSV-2 incidence was 22.1 per 100 person-years (p < 0.001 compared to incidence in men), and was associated with incident HIV-1 infection (aIRR 8.9, 95% CI 3.6–21.8) and vaginal washing with soap (aIRR 1.9, 95% CI 1.0–3.4).

Conclusions

HSV-2 incidence in these men and women is among the highest reported, and is associated with HIV-1 acquisition. While vaginal washing with soap may increase HSV-2 risk in women, genital hygiene may be protective in men.

Keywords: HSV-2, HIV-1, herpes, prevalence, incidence, Kenya, hygiene

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is the leading cause of genital ulcers worldwide and an important cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality.1 Although its precise role remains unclear,2, 3 HSV-2 infection has been associated with increased HIV-1 transmission risk, likely due to genital mucosal inflammation and ulceration.4 Because HSV-2 infection is a lifelong condition with frequent recurrences, identifying potential risk reduction strategies is important, particularly among persons at high risk for HIV-1 acquisition.5

Risk factors for incident HSV-2 infection have been evaluated in African women who report high-risk sexual behavior, including female sex workers (FSW), in whom HSV-2 incidence is among the highest reported (up to 23 per 100 person-years).6, 7 Several recent studies have evaluated HSV-2 acquisition risk among sexually active African men, reporting incidence rates ranging from 2.1 to 4.9 per 100 person-years.8, 9 High-risk African men, in particular men who have sex with men (MSM) and male sex workers (MSW), have largely been neglected in the epidemic, but their role in the sexual transmission of HIV-1 in this region has received increasing attention.10 To date, no studies have reported risk factors for HSV-2 infection among African MSM and MSW. Our aim was to identify factors associated with incident HSV-2 infection among HIV-1-seronegative MSM and MSW on the Kenyan Coast. We compare our results to an analysis of factors associated with incident HSV-2 infection among high-risk HIV-1-seronegative women, the majority FSW, in the same community.

Materials and Methods

Study population

In July 2005, a prospective study of men and women at high risk for HIV-1 acquisition was initiated in a clinic north of Mombasa, Kenya. Adults aged 18–49 years were eligible if they met any of the following criteria: transactional sex work, recent sexually transmitted infection (STI), multiple sexual partners, anal sex, or regular sex with an HIV-1-infected partner. The initial focus of recruitment was on FSW and discordant couples. MSM and MSW became a focus when this group was identified, approximately one year later. The population for this study includes all eligible men and women who consented to screening and enrollment from July 2005 through December 2008.

Clinical Procedures

Detailed procedures have been described previously.11 Briefly, eligible persons underwent confidential HIV counseling and testing, then completed face-to-face or audio computer-assisted interviews using standardized questionnaires to ascertain recent sexual behavior and genitourinary symptoms.12 Participants were asked how many times in the past week they had washed their genitals (for men) or washed inside the vagina (for women) with water or soap (including detergent, or antiseptic). A physical examination was performed, including collection of specimens for STI screening. Genital ulcers and circumcision status were noted. A blood sample was obtained for HIV-1 serological testing, and aliquots were archived at −80°C. Screening samples were not initially stored for persons who tested HIV-1 seropositive, but were archived starting in March 2006.

Persons who tested HIV-1 seronegative were enrolled and underwent monthly (if receptive anal intercourse reported) or quarterly follow-up visits with procedures as outlined above. HIV-1-infected persons were offered enrolment into a parallel cohort for clinical follow-up without storage of research samples. Participants with genital symptoms were provided syndromic treatment, and laboratory-diagnosed infections were treated following Kenyan Ministry of Health guidelines. At each visit, risk reduction counseling, condoms, and lubricants were provided. The study was approved by ethical review boards at the Kenya Medical Research Institute and the University of Washington. All participants provided written informed consent.

Laboratory testing

HIV-1 testing was performed using two rapid test kits in parallel (Determine, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA; Unigold, Trinity Biotech plc, Bray, Ireland). Discrepant rapid HIV-1 test results were resolved using an ELISA (Genetic System HIV-1/2 plus O EIA, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, Washington, USA). Incident HIV-1 infection was defined as negative serology at enrolment followed by positive serology results during follow-up. Prevalent syphilis was diagnosed by a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titre confirmed by Treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay (TPHA). Incident syphilis was defined as a four-fold increase in RPR titre confirmed by TPHA.

Serological testing for HSV-2 was performed on archived samples using a type-specific ELISA (HerpeSelect®-2, Focus Diagnostics, Cypress, California, USA), performed according to manufacturer’s protocol. An index value >3.5 (ratio of the optical density [OD] of the sample to that of the standard calibrator) was considered positive, in accordance with published studies on the sensitivity and specificity of HerpeSelect in East Africa.13-16 All enrolment samples were tested for HSV-2, regardless of HIV-1 serostatus. Participants who were HSV-2-seronegative and had follow-up samples available had their last follow-up samples tested to define HSV-2 serostatus at the end of the study. For participants HSV-2-seropositive at their last visit, intervening samples were tested to determine the seroconversion time point. The archived enrollment samples were serum and follow-up samples were plasma. The HSV-2 ELISA used in this study provides similar results with both sample types.17 Serologic testing was repeated on a randomly selected 10% of enrolment specimens for quality control purposes.

Data analysis

Separate analyses were conducted for men and women. All participants with enrollment results were included for estimation of HSV-2 seroprevalence. HSV-2 prevalence for groups was compared by Pearson Chi square test. Prevalence ratios (PR) were used to measure associations between potential risk factors at enrollment and prevalent HSV-2 infection. A multivariate Poisson model was used to estimate adjusted PR (aPR).

Participants who were HSV-2-seronegative at baseline and had at least one follow-up sample available for testing through July 2009 were included in the HSV-2 incidence analysis. The date of HSV-2 infection was estimated at the midpoint between the last negative and first positive test result. Incidence rates for groups were compared by log rank test. We evaluated potential risk factors that were fixed (e.g., demographics, circumcision status) or time-varying covariates (genital washing, alcohol use, sexual behaviors, HIV status). Incidence rate ratios (IRR) were used to measure associations between potential risk factors and HSV-2 incidence per 100 person-years of follow-up. A multivariate Poisson model was used to estimate adjusted IRR (aIRR).

Genital symptoms and exam findings (e.g., genital ulcers) were not included for modeling because they were likely a consequence, rather than a cause, of HSV-2 serostatus. Factors identified a priori (age and HIV-1 status) and factors associated with prevalent or incident HSV-2 with p≤0.10 were included in final multivariate modeling. We assessed the robustness of the main analysis by excluding observations with index values >1.1 and ≤3.5,13-16 as values in this range may represent early incident HSV-2 infection.18 Stata version 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) was used for analysis. Statistical significance was evaluated at the 0.05 level.

Results

Population

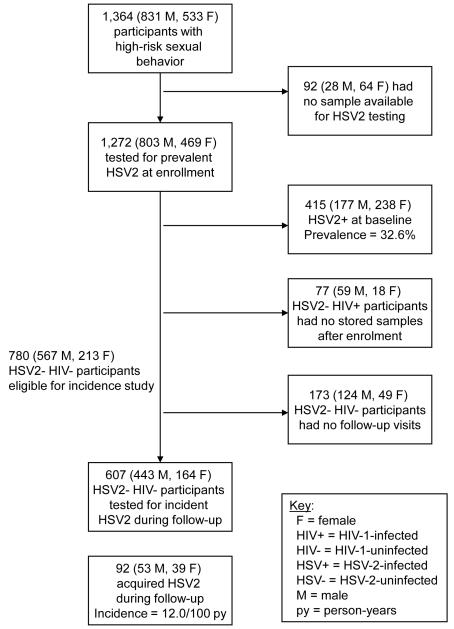

Between July 2005 and December 2008, 1,364 adults were enrolled, of whom 1,272 (93.3%) had stored samples available for HSV-2 testing (Figure 1). Those with no archived sample were more likely to be HIV-1 seropositive (95.5% versus 17.0%; p<0.001) and female (69.7% versus 36.9%; p<0.001). Other baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram detailing numbers enrolled, numbers tested for prevalent HSV-2, and numbers included for incidence analysis.

Of the 1,272 participants with enrolment samples available, 803 (63.1%) were males. Most participants were single (72.0% of men and 59.5% of women). The median age was 26 years for both sexes (interquartile range [IQR], 22–33 years for men, 22–31 years for women). Few participants reported formal employment (28.1% of men and 7.3% of women). The majority reported transactional sex work in the past 3 months (55.3% of men and 73.6% of women). Overall HIV-1 prevalence was 17.0%, and was higher in women than in men (20.9% versus 14.7%, p=0.004).

HSV-2 Prevalence and Risk Factors

At enrolment, 415 participants (32.6%) were HSV-2-seropositive. Prevalence was higher among women than men (50.8% versus 22.0%, p<0.001). Genital ulcers were detected at a slightly higher frequency among HSV-2-seropositive compared to seronegative participants during the enrolment examination, but these differences were not significant (3.6% versus 3.1% for men, p=0.75; 8.8% versus 6.4% for women, p=0.35). Among men, HSV-2 prevalence increased with increasing age, alcohol use, prevalent syphilis, and prevalent HIV-1 infection (Table 1). There was no association between prevalent HSV-2 and male sexual orientation or sex work. Among women, HSV-2 prevalence increased with increasing age, lower educational attainment, and prevalent HIV-1 infection (Table 2). There was no association between prevalent HSV-2 and female sex work. Only two women (0.4%) reported homosexual activity.

Table 1.

Factors Associated with Prevalent HSV-2 Infection at Enrolment among 803 Men

| Characteristics and Behaviours | HSV-2 positive, proportion (%) |

Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CI) | Wald P-value | aPR (95% CI) | Wald P-value | ||

| Age Group | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 18-24 yrs | 34/304 (11.2) | Referent | Referent | ||

| 25-34 yrs | 79/333 (23.7) | 2.12 (1.46 – 3.07) | 1.69 (1.15 – 2.47) | ||

| >34 yrs | 64/166 (38.6) | 3.45 (2.38 – 4.99) | 2.75 (1.75 – 4.33) | ||

| Education | 0.33 | ||||

| None | 14/43 (32.6) | Referent | |||

| Primary | 90/409 (22.0) | 0.68 (0.42 – 1.08) | |||

| Secondary | 56/272 (20.6) | 0.63 (0.39 – 1.03) | |||

| Higher / Tertiary | 17/79 (21.5) | 0.66 (0.36 – 1.21) | |||

| Ever Married | < 0.001 | 0.51 | |||

| No | 106/578 (18.3) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 71/225 (31.6) | 1.72 (1.33 – 2.23) | 1.11 (0.81 – 1.54) | ||

| Employment | 0.16 | ||||

| None | 52/285 (18.3) | Referent | |||

| Self | 69/292 (23.6) | 1.30 (0.94 – 1.79) | |||

| Formal | 56/226 (24.8) | 1.36 (0.97 – 1.90) | |||

| Circumcised | 0.50 | ||||

| No | 20/103 (19.4) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 157/700 (22.4) | 1.16 (0.76 –1.75) | |||

| Transactional sex past 3 months | 0.002 | 0.09 | |||

| No | 97/359 (27.0) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 80/444 (18.0) | 0.67 (0.51 – 0.87) | 0.79 (0.61 – 1.04) | ||

| Sexual orientation | 0.99 | ||||

| Heterosexual | 67/307 (21.8) | Referent | |||

| Homosexual | 40/179 (22.4) | 1.02 (0.72 – 1.45) | |||

| Bisexual | 70/317 (22.1) | 1.01 (0.75 – 1.36) | |||

| Alcohol use past month | 0.09 | 0.04 | |||

| No | 61/322 (18.9) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 116/481 (24.1) | 1.27 (0.97 – 1.68) | 1.32 (1.01 – 1.72) | ||

| Insertive anal intercourse past 3 months | 0.77 | ||||

| No | 90/416 (21.6) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 87/387 (22.5) | 1.04 (0.80 -1.35) | |||

| Receptive anal intercourse past 3 months | 0.84 | ||||

| No | 105/471 (22.3) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 72/332 (21.7) | 0.97 (0.75 -1.27) | |||

| Prevalent Syphilis | < 0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 165/780 (21.2) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 12/23 (52.2) | 2.47 (1.63 – 3.73) | 2.16 (1.39 -3.35) | ||

| Prevalent HIV | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 121/685 (17.7) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 56/118 (47.5) | 2.69 (2.09 – 3.45) | 2.39 (1.84 – 3.10) | ||

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Prevalent HSV-2 Infection at Enrolment among 469 Women

| Characteristics and Behaviours | HSV-2 positive, proportion (%) |

Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CI) | Wald P-value |

aPR (95% CI) | Wald P-value |

||

| Age Group | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| 18-24 yrs | 77/201 (38.3) | Referent | Referent | ||

| 25-34 yrs | 98/191 (51.3) | 1.34 (1.07 – 1.67) | 1.22 (0.98 – 1.52) | ||

| >34 yrs | 63/77 (81.8) | 2.14 (1.74 – 2.62) | 1.79 (1.43 – 2.25) | ||

| Education | 0.002 | 0.02 | |||

| None | 33/48 (68.8) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Primary | 119/222 (53.6) | 0.78 (0.62 – 0.98) | 0.80 (0.64 – 1.01) | ||

| Secondary | 72/154 (46.8) | 0.68 (0.53 – 0.88) | 0.72 (0.55 – 0.93) | ||

| Higher / Tertiary | 14/45 (31.1) | 0.45 (0.28 – 0.73) | 0.53 (0.33 – 0.83) | ||

| Ever Married | 0.005 | 0.91 | |||

| No | 127/279 (45.5) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 111/190 (58.4) | 1.28 (1.08 – 1.53) | 1.00 (0.81 – 1.21) | ||

| Employment | 0.69 | ||||

| None | 85/170 (50.0) | Referent | |||

| Self | 138/265 (52.1) | 1.04 (0.86 – 1.26) | |||

| Formal | 15/34 (44.1) | 0.88 (0.59 – 1.33) | |||

| Hormonal contraceptive use | 0.31 | ||||

| No | 183/351 (52.1) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 55/118 (46.6) | 0.89 (0.72 – 1.11) | |||

| Transactional sex past 3 months | 0.16 | ||||

| No | 56/124 (45.2) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 182/345 (52.8) | 1.17 (0.94 – 1.45) | |||

| Alcohol use past month | 0.10 | 0.77 | |||

| No | 88/157 (56.1) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 150/312 (48.1) | 0.86 (0.72 – 1.03) | 0.97 (0.82 – 1.16) | ||

| Anal intercourse past 3 months | 0.14 | ||||

| No | 174/356 (48.9) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 64/113 (56.6) | 1.16 (0.96 – 1.41) | |||

| Prevalent Syphilis | 0.04 | 0.93 | |||

| No | 226/452 (50.0) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 12/17 (70.6) | 1.41 (1.02 – 1.95) | 1.02 (0.73 – 1.42) | ||

| Prevalent HIV | <0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 158/371 (42.6) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 80/98 (81.6) | 1.92 (1.65 – 2.23) | 1.72 (1.47 – 2.01) | ||

Incidence risk factors

Of 857 volunteers who were HSV-2-seronegative at baseline, 607 individuals (all HIV-1-seronegative) had subsequent blood samples available for testing, contributing 767.1 person-years of follow-up. Median follow-up time was 16.8 months (IQR, 7.6 – 21.2 months). Among participants not contributing to follow-up, 77 were HIV-1-seropositive and therefore had no stored samples, and the remaining 173 (22.2% of 780 HIV-1-seronegative participants) never returned (Figure 1). HIV-1-seronegative, HSV-2-seronegative participants who did not return were younger (58.4% versus 45.6% <25; p=0.003) and more likely to be single (80.4% versus 69.5%; p=0.005) than those retained.

The HSV-2 incidence rate during follow-up was 9.0 per 100 person-years among men (Table 3) and 22.1 per 100 person-years among women (Table 4). This difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). No incident syphilis occurred at the same time as HSV-2 acquisition among either men or women.

Table 3.

Risk Factors for Incident HSV-2 Infection in 443 Men

| Characteristics and Behaviours |

Failures per PY |

Incident /100 PY (95% CI) |

Univariate analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (95% CI) | Wald P-value |

IRR (95% CI) | Wald P- value |

|||

| Age Group at visit | 0.002 | 0.15 | ||||

| 18-24 yrs | 7 / 204.7 | 3.4 (1.6 – 7.2) | Referent | Referent | ||

| 25-34 yrs | 27 / 267.4 | 10.1 (6.9 – 14.7) | 2.95 (1.29 – 6.75) | 1.97 (0.79 – 4.92) | ||

| >34 yrs | 19 / 118.6 | 16.0 (10.2 – 25.1) | 4.68 (1.96 – 11.18) | 2.83 (0.99 – 8.11) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| None | 2 / 23.9 | 8.4 (2.1 – 33.4) | Referent | 0.32 | ||

| Primary | 33 / 297.2 | 11.1 (7.9 – 15.6) | 1.32 (0.34 – 5.15) | |||

| Secondary | 13 / 211.7 | 6.1 (3.6 – 10.6) | 0.73 (0.18 – 3.02) | |||

| Higher / Tertiary | 5 / 57.8 | 8.6 (3.6 – 20.8) | 1.03 (0.21 – 5.00) | |||

| Ever Married | 0.05 | 0.69 | ||||

| No | 31 / 418.7 | 7.4 (5.2 – 10.5) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 22 / 172.0 | 12.8 (8.4 – 19.4) | 1.72 (1.00 – 2.98) | 1.15 (0.57 – 2.32) | ||

| Employment | 0.58 | |||||

| None | 16 / 203.6 | 7.9 (4.8 – 12.8) | Referent | |||

| Self | 18 / 212.4 | 8.5 (5.3 – 13.5) | 1.08 (0.56 – 2.09) | |||

| Formal | 19 /174.7 | 10.9 (6.9 – 17.1) | 1.39 (0.72 – 2.68) | |||

| Circumcised at enrolment |

1.00 | |||||

| No | 4 / 44.7 | 8.9 (3.4 – 23.8) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 49 / 545.9 | 9.0 (6.8 – 11.9) | 1.00 (0.36 – 2.76) | |||

| Genital washing with soap past week |

0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| No | 5 / 19.3 | 25.9 (10.8 – 62.3) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 48 / 571.0 | 8.4 (6.3 – 11.2) | 0.32 (0.14 – 0.76) | 0.33 (0.13 – 0.81) | ||

| Transactional sex past 3 months |

0.59 | |||||

| No | 33 / 346.6 | 9.5 (6.8 – 13.4) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 20 / 243.4 | 8.2 (5.3 – 12.7) | 0.86 (0.50 – 1.49) | |||

| Having sex with men past 3 months |

0.20 | |||||

| No | 29 / 271.9 | 10.7 (7.4 – 15.3) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 24 / 318.7 | 7.5 (5.0 – 11.2) | 0.71 (0.41 – 1.21) | |||

| New sex partner past month |

0.02 | 0.18 | ||||

| No | 35 / 297.2 | 11.8 (8.5 – 16.4) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 18 / 293.5 | 6.1 (3.9 – 9.7) | 0.52 (0.30 – 0.91) | 0.64 (0.33 – 1.23) | ||

| Total sex partners past month |

0.22 | |||||

| None | 9 / 77.7 | 11.6 (6.0 – 22.3) | Referent | |||

| 1 | 20 / 175.8 | 11.4 (7.3 – 17.6) | 0.98 (0.45 – 2.15) | |||

| 2-4 | 18 / 206.3 | 8.7 (5.5 – 13.8) | 0.75 (0.34 – 1.66) | |||

| >4 | 6 / 130.9 | 4.6 (2.1 – 10.2) | 0.39 (0.14 – 1.11) | |||

| Condom use for anal sex past 3 months1 |

0.31 | |||||

| Always | 5 / 103.9 | 4.8 (2.0 – 11.6) | Referent | |||

| Inconsistent | 13 / 126.1 | 10.3 (6.0 – 17.7) | 2.15 (0.79 – 5.87) | |||

| Never | 5 / 49.7 | 10.1 (4.2 – 24.2) | 2.07 (0.62 – 6.99) | |||

| Overall condom use past 3 months2 |

0.06 | 0.10 | ||||

| Always | 10 / 174.3 | 5.7 (3.1 – 10.7) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Inconsistent | 17 / 214.7 | 7.9 (4.9 – 12.7) | 1.38 (0.64 – 2.97) | 1.30 (0.53 – 3.16) | ||

| Never | 18 / 130.8 | 13.8 (8.7 – 21.8) | 2.40 (1.11 – 5.16) | 2.36 (1.07 – 5.23) | ||

| Alcohol use past month | 0.62 | |||||

| No | 24 / 247.9 | 9.7 (6.5 – 14.4) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 29 / 342.1 | 8.5 (5.9 – 12.2) | 0.87 (0.51 – 1.49) | |||

| Insertive anal intercourse past 3 months |

0.22 | |||||

| No | 38 / 376.6 | 10.1 (7.3 – 13.9) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 15 / 213.7 | 7.0 (4.2 – 11.6) | 0.69 (0.39 – 1.25) | |||

| Receptive anal intercourse past 3 months |

0.23 | |||||

| No | 36 / 442.2 | 8.1 (5.9 – 11.3) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 17 / 148.1 | 11.5 (7.1 – 18.5) | 1.41 (0.80 – 2.48) | |||

| Incident HIV | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||

| No | 46 / 559.8 | 8.2 (6.2 – 11.0) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 7 / 30.8 | 22.7 (10.8 – 47.7) | 2.77 (1.19 – 6.41) | 3.95 (1.25 –12.43) | ||

Among men reporting anal sex.

Among men reporting any type of sex.

Table 4.

Risk Factors for Incident HSV-2 Infection in 164 Women

| Characteristics and Behaviours |

Failures / PY |

Incident /100 PY | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (95% CI) | Wald P-value |

IRR (95% CI) | Wald P-value |

|||

| Age group at follow-up | 0.39 | 0.59 | ||||

| 18-24 yrs | 15 / 82.9 | 18.1 (10.9 – 30.0) | Referent | Referent | ||

| 25-34 yrs | 19 / 79.4 | 23.9 (15.3 – 37.5) | 1.34 (0.68 – 2.64) | 1.26 (0.65 – 2.44) | ||

| >34 yrs | 5 / 14.3 | 35.1 (14.6 – 84.3) | 1.95 (0.73 – 5.21) | 1.69 (0.58 – 4.94) | ||

| Education | 0.11 | |||||

| None | 4 / 8.2 | 48.7 (18.3 – 129.8) | Referent | |||

| Primary | 19 / 80.7 | 23.6 (15.0 – 36.9) | 0.49 (0.20 – 1.18) | |||

| Secondary | 9 / 63.8 | 14.1 (7.3 – 27.1) | 0.30 (0.11 – 0.81) | |||

| Higher / Tertiary | 7 / 23.8 | 29.4 (14.0 – 61.6) | 0.61 (0.21 – 1.77) | |||

| Ever Married | 0.06 | 0.09 | ||||

| No | 19 / 112.9 | 16.8 (10.7 – 26.4) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 20 / 63.6 | 31.5 (20.3 – 48.8) | 1.83 (0.99 – 3.40) | 1.76 (0.92 – 3.36) | ||

| Employment | 0.63 | |||||

| None | 17 / 63.7 | 26.7 (16.6 – 42.9) | Referent | |||

| Self | 19 / 99.4 | 19.1 (12.2 – 30.0) | 0.72 (0.38 – 1.39) | |||

| Formal | 3 / 13.4 | 22.4 (7.2 – 69.5) | 0.84 (0.27 – 2.66) | |||

| Hormonal contraceptive use | 0.12 | |||||

| No | 31 / 120.2 | 25.8 (18.1 – 36.7) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 8 / 56.3 | 14.2 (7.1 – 28.4) | 0.55 (0.26 – 1.17) | |||

| Washing inside the vagina with soap past week |

0.06 | 0.04 | ||||

| No | 24 / 131.5 | 18.3 (12.2 – 27.2) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 15 / 45.0 | 33.3 (20.1 – 55.3) | 1.80 (0.99 – 3.29) | 1.87 (1.02 – 3.43) | ||

| Transactional sex past 3 months |

0.35 | |||||

| No | 22 / 86.2 | 25.5 (16.8 – 38.8) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 17 / 90.3 | 18.8 (11.7 – 30.3) | 0.75 (0.40 – 1.38) | |||

| New sex partner past month | 0.50 | |||||

| No | 26 / 108.4 | 24.0 (16.3 – 35.2) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 13 / 68.1 | 19.1 (11.1 – 32.9) | 0.80 (0.42 – 1.53) | |||

| Total sex partners past month |

0.41 | |||||

| None | 7 / 20.9 | 33.5 (15.9 – 70.2) | Referent | |||

| 1 | 16 / 67.2 | 23.8 (14.6 – 38.8) | 0.71 (0.31 – 1.64) | |||

| 2- 4 | 11 / 51.5 | 21.4 (11.8 – 38.6) | 0.65 (0.26 – 1.59) | |||

| Above 4 | 5 / 36.8 | 13.6 (5.6 – 32.6) | 0.40 (0.14 – 1.16) | |||

| Overall condom use past 3 months1 |

0.77 | |||||

| Always | 10 / 46.8 | 21.4 (11.5 – 39.7) | Referent) | |||

| Inconsistent | 8 / 48.5 | 16.5 (8.2 – 33.0) | 0.76 (0.31 – 1.91) | |||

| Never | 13 / 58.1 | 22.4 (13.0 – 38.5) | 1.05 (0.46 – 2.39) | |||

| Alcohol use past month | 0.28 | |||||

| No | 22 / 83.7 | 26.3 (17.3 – 39.9) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 17 / 91.9 | 18.5 (11.5 – 29.7) | 0.71 (0.38 – 1.32) | |||

| Anal intercourse past 3 months |

0.47 | |||||

| No | 38 / 166.9 | 22.8 (16.6 – 31.3) | Referent | |||

| Yes | 1 / 9.3 | 10.8 (1.5 – 76.4) | 0.49 (0.07 – 3.36) | |||

| Incident HIV | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 36 / 174.3 | 20.6 (14.9 – 28.6) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 3 / 2.1 | 141.0 (45.5 – 437.3) | 6.65 (2.22 – 19.92) | 8.88 (3.62 – 21.78) | ||

Among women reporting any type of sex.

N.B. Condom use for anal sex in the past 3 months is omitted because there was only 1 event (in a woman reporting always using condoms for anal sex), and the model would not converge.

Among men, HSV-2 acquisition during follow-up was associated with genital ulcer disease detected by examination (IRR 4.3, 95% CI 1.1–17.3). In multivariate analysis, HSV-2 acquisition was associated with HIV-1 acquisition (aIRR 3.9, 95% CI 1.3–12.4) and use of soap for genital washing was protective (aIRR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.8). A dose-response relationship between genital washing with soap and incident HSV-2 infection could be demonstrated: incidence rates were estimated at 25.9, 10.2, 8.3, and 5.7 per 100 person-years with no soap use, soap use ≤7 times weekly, soap use 8-14 times weekly, and soap use >14 times weekly. There was a significant reduction in HSV-2 incidence for every increment in the frequency of washing with soap (IRR 0.7, 95% CI 0.4–1.0, p=0.03).

Because we were interested in the effect of receptive anal intercourse on HSV-2 acquisition, we tested the effect of adding this variable to the multivariate model. If receptive anal intercourse is included a priori, its association with HSV-2 acquisition is of borderline significance (aIRR 2.0, 95% CI 1.0–4.1, p=0.057) and HSV-2 acquisition is no longer significantly associated with HIV-1 acquisition (aIRR 2.6, 95% CI 0.7–9.3, p=0.1). Soap use remains a significant predictor in this model (aIRR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.8, p=0.01).

Among women, HSV-2 acquisition was not associated with genital ulcer disease detected by examination (aIRR 0.6, 95% CI 0.1–4.1). In multivariate analysis, HSV-2 acquisition was associated with incident HIV-1 infection (aIRR 8.9, 95% CI 3.6–21.8) and washing inside the vagina with soap (aIRR 1.9, 95% CI 1.0–3.4). There was no dose-response relationship between vaginal washing with soap and incident HSV-2 infection: incidence rates were estimated at 18.3, 37.1, 33.9, and 27.4 per 100 person-years with no vaginal soap use, soap use ≤7 times weekly, soap use 8-14 times weekly, and soap use >14 times weekly. The addition of receptive anal intercourse to the model did not change these results.

Sensitivity Analysis

In the sensitivity analysis in which HSV-2 ELISA index values was >1.1 and ≤3.5 were excluded, associations with HSV-2 prevalence were unchanged. Power for the incidence analysis was reduced, as only seroconversions from low negative index values are included. HIV-1 remained significantly associated with incident HSV-2 infection in both men and women. Although risk estimates were similar to those from the main analysis, soap use for vaginal washing among women (aIRR 1.4, 95% CI 0.4–5.1) and for genital washing among men (0.6, 95% 0.2–2.2) were no longer significantly associated with incident HSV-2.

Discussion

The overall 32.6% HSV-2 prevalence in this cohort is close to the 35.4% national prevalence reported among Kenyans adults from 15–64 years of age (42.3% among women versus 26.1% among men).19 In this cohort of young individuals reporting high-risk sex, women had a higher HSV-2 prevalence than men (50.8% versus 22.0%). Although the majority of men and women in this cohort reported recent transactional sex work, transactional sex was not associated with HSV-2 prevalence or incidence. Overall, we found somewhat lower HSV-2 prevalence than reported in similar East African populations. For example, our observed HSV-2 prevalence in men was lower than that reported among young, heterosexual men in Kisumu, Kenya (27.6%) and in a similar cohort of men in Rakai, Uganda (33.8%)8, 20 Among women, the HSV-2 prevalence (50.8%) was lower than the 80% prevalence reported in both an FSW cohort in Mombasa, Kenya and in female recreational facility workers (35% transactional sex workers) in northwestern Tanzania.6, 21 We found that HSV-2 prevalence was strongly associated with increasing age and prevalent HIV-1 infection in both men and women, as reported elsewhere.8, 19, 21 We also found that HSV-2 prevalence was associated with alcohol use and prevalent syphilis in men and with lower educational level in women, likely reflecting a higher probability of exposure in these groups.

In this study, the HSV-2 incidence estimated in men (9.0/100 person-years) is twice as high as estimates for sexually active men in the general population in sub-Saharan Africa and almost five times higher than that reported among North American MSM.8, 9, 22 The estimated incidence in women (22.1/100 person-years) is very close to that reported for a FSW cohort in the same geographic area.6 The higher HSV-2 incidence among women in this cohort contrasts with their lower HIV-1 incidence compared to MSM in this cohort (3.2/100 person-years versus 8.6/100 person-years).23 Nevertheless, HSV-2 incidence was associated with incident HIV-1 infection among both men and women, as reported previously in a number of studies.24

In our analysis of HSV-2 incidence in men, the association with HIV-1 infection was weakened after inclusion of receptive anal intercourse in the model, suggesting that the association between HSV-2 incidence and HIV-1 acquisition may be partly mediated through this high-risk behavior. Although our finding of a 2-fold increase in HSV-2 acquisition risk among men reporting receptive anal intercourse did not reach statistical significance, unprotected receptive anal intercourse has previously been reported to increase HSV-2 acquisition risk among North American MSM.22 For many of our study participants, unprotected receptive anal intercourse may therefore be an important factor increasing risk of both HIV-1 and HSV-2 infection.

At each visit, we asked participants the number of times in the past week they had washed their genitals (for men) or inside their vagina (for women) with soap, including use of detergent or antiseptic. We found that using soap for genital hygiene was associated with a decreased risk of HSV-2 acquisition among men and an increased risk among women. There is some biologic plausibility to this finding, as the moist mucosal epithelium of the vagina may be more subject to irritation by soaps and abrasive washcloths than the keratinized squamous epithelium that protects the penis. We found a dose-response relationship to washing with soap among the men in our study, with greater protection among those who washed more frequently. Since the vast majority (87%) of our male participants were circumcised, we were unable to evaluate the effect of genital washing with soap in uncircumcised men, who may have increased vulnerability to genital infections.25 Among women, washing inside the vagina with soap was associated with higher HSV-2 acquisition risk, but no dose-response relationship was apparent. Vaginal washing, especially washing with soap, has been associated with increased HIV-1 acquisition risk among Kenyan women after adjustment for demographic factors, sexual behavior, and genital infections including bacterial vaginosis.26 While the frequency of vaginal douching was associated with recent HSV-2 infection among women in one African study,21 another study reported no association between vaginal washing and HSV-2 acquisition.6 The associations we found between genital washing with soap, detergent or antiseptic and HSV-2 acquisition in both sexes are intriguing, but were not robust in the sensitivity analysis and require validation.

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to evaluate risk factors for incident HSV-2 infection in African men reporting high-risk sexual behaviors. This strength should be considered in the context of a number of important limitations. First, our sample size and follow-up duration were limited, especially for women. Second, we were unable to confirm HSV-2 seroconversions with Western blot testing due to budgetary constraints. However, the HerpeSelect assay has optimal sensitivity and specificity at an index value of 3.4–3.5, and we conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the extent to which results were affected by possible misclassification of early incident HSV-2 infection.18 Third, our risk behavior assessments are based on self report, with the majority taking place on a quarterly basis. Therefore, recall and social desirability bias, as well as measurement error due to the relatively long interval between visits are a likely source of residual confounding.12 Finally, loss to follow-up in this mobile population is relatively high and may affect our risk estimates.

We have detected a very high incidence of HSV-2 acquisition among the men and women in this study, among the highest reported for each sex to date. We have confirmed that HSV-2 risk is strongly intertwined with that for HIV-1, another sexually transmitted viral infection with life-long consequences. These findings reinforce the need for promotion of safe sex as the primary method for prevention of both HSV-2 and HIV-1 infections, as well as other STI. While the role of genital hygiene in HSV-2 acquisition is yet unclear, women should avoid vaginal washing in order to lower their risk of HIV-1 acquisition,26, 27 and our results suggest an added benefit in terms of HSV-2 prevention. In addition, men may benefit in many ways from good hygiene, including washing their genitals with soap. However, a specific recommendation to have men wash with soap in order to prevent HSV-2 acquisition would be premature.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study participants and staff in the HIV/STI project of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) in Kilifi, whose commitment and cooperation made this study possible. We thank the Director, KEMRI, for permission to publish this manuscript, and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) for design and support of the HIV-1-seronegative cohort study and for sharing data on HIV-1 acquisition.

This study is made possible in part by the generous support of the American people through a grant to the IAVI from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of IAVI and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Funding was provided by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757), which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NCCAM).

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370:2127–2137. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61908-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobian AA, Ssempijja V, Kigozi G, et al. Incident HIV and herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among men in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2009;23:1589–1594. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glynn JR, Biraro S, Weiss HA. Herpes simplex virus type 2: a key role in HIV incidence. AIDS. 2009;23:1595–1598. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e15e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald A, Link K. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in herpes simplex virus type 2-seropositive persons: a meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:45–52. doi: 10.1086/338231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Farrell N, Moodley P, Sturm AW. Genital herpes in Africa: time to rethink treatment. Lancet. 2007;370:2164–2166. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chohan V, Baeten JM, Benki S, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for herpes simplex virus type 2 acquisition among high-risk HIV-1 seronegative women in Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:489–492. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tassiopoulos KK, Seage G, 3rd, Sam N, et al. Predictors of herpes simplex virus type 2 prevalence and incidence among bar and hotel workers in Moshi, Tanzania. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:493–501. doi: 10.1086/510537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobian AA, Charvat B, Ssempijja V, et al. Factors associated with the prevalence and incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among men in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:945–949. doi: 10.1086/597074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Taljaard D, Lissouba P, et al. Effect of HSV-2 serostatus on acquisition of HIV by young men: results of a longitudinal study in Orange Farm, South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:958–964. doi: 10.1086/597208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AD, Tapsoba P, Peshu N, et al. Men who have sex with men and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2009;374:416–422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders EJ, Graham SM, Okuku HS, et al. HIV-1 infection in high risk men who have sex with men in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS. 2007;21:2513–2520. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2704a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Elst EM, Okuku HS, Nakamya P, et al. Is audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) useful in risk behaviour assessment of female and male sex workers, Mombasa, Kenya? PLoS One. 2009;4:e5340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogrefe W, Su X, Song J, et al. Detection of herpes simplex virus type 2-specific immunoglobulin G antibodies in African sera by using recombinant gG2, Western blotting, and gG2 inhibition. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3635–3640. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3635-3640.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laeyendecker O, Henson C, Gray RH, et al. Performance of a commercial, type-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of herpes simplex virus type 2-specific antibodies in Ugandans. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1794–1796. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1794-1796.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith JS, Bailey RC, Westreich DJ, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 antibody detection performance in Kisumu, Kenya, using the Herpeselect ELISA, Kalon ELISA, Western blot and inhibition testing. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:92–96. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serwadda D, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus acquisition associated with genital ulcer disease and herpes simplex virus type 2 infection: a nested case-control study in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1492–1497. doi: 10.1086/379333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Hillier SL. Plasma versus serum for detection of herpes simplex virus type 2-specific immunoglobulin G antibodies with a glycoprotein G2-based enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2758–2759. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2758-2759.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeGoff J, Mayaud P, Gresenguet G, et al. Performance of HerpeSelect and Kalon assays in detection of antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 2. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1914–1918. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02332-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2007: Preliminary Report. Kenya Ministry of Health; Nairobi, Kenya: 2008. National AIDS and STI Control Programme. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta SD, Moses S, Agot K, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 infection among young uncircumcised men in Kisumu, Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:42–48. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.025718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M, et al. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus type 2 and HIV among women at high risk in northwestern Tanzania: preparing for an HSV-2 intervention trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:631–642. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b2d9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown EL, Wald A, Hughes JP, et al. High risk of human immunodeficiency virus in men who have sex with men with herpes simplex virus type 2 in the EXPLORE study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:733–741. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mwangome M, Okuku HS, Fegan G, et al. MSM sex workers maintain a high HIV-1 incidence over time in Mombasa, Kenya. 5th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; Cape Town, South Africa: Jul, 2009. Abstract 3544. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson D, Politch JA, Pudney J. HIV infection and immune defense of the penis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00941.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClelland RS, Lavreys L, Hassan WM, et al. Vaginal washing and increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition among African women: a 10-year prospective study. AIDS. 2006;20:269–273. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196165.48518.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chersich MF, Hilber A Martin, Schmidlin K, et al. Association between intravaginal practices and HIV acquisition in women: individual patient data meta-analysis of cohort studies in sub-Saharan Africa. 5th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; Cape Town, South Africa: Jul, 2009. Abstract TUAC204. [Google Scholar]