Abstract

The objective of this study was to ascertain the effects of a mouthwash prepared with Triphala on dental plaque, gingival inflammation, and microbial growth and compare it with commercially available Chlorhexidine mouthwash. This study was conducted after ethics committee approval and written consent from guardians (and assent from the children) were obtained. A total of 1431 students in the age group 8–12 years, belonging to classes fourth to seventh, were the subjects for this study. The Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) of the subjects was determined using a questionnaire. The students were divided into three groups namely, Group I (n = 457) using Triphala mouthwash (0.6%), Group II (n = 440) using Chlorhexidine mouthwash (0.1%) (positive control), and Group III (n = 412) using distilled water (negative control). The assessment was carried out on the basis of plaque scores, gingival scores, and the microbiological analysis (Streptococcus and lactobacilli counts). Statistical analysis for plaque and gingival scores was conducted using the paired sample t-test (for intragroup) and the Tukey's test (for intergroup conducted along with analysis of variance test). For the Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus counts, Wilcoxon and Mann–Whitney test were applied for intragroup and intergroup comparison, respectively. All the tests were carried out using the SPSS software. Both the Group I and Group II showed progressive decrease in plaque scores from baseline to the end of 9 months; however, for Group III increase in plaque scores from the baseline to the end of 9 months was noted. Both Group I and Group II showed similar effect on gingival health. There was inhibitory effect on microbial counts except Lactobacillus where Triphala had shown better results than Chlorhexidine. It was concluded that there was no significant difference between the Triphala and the Chlorhexidine mouthwash.

Keywords: Triphala, Chlorhexidine, dental plaque, gingival inflammation, microbial growth

INTRODUCTION

Over a period of time it has been observed that the cost for the preservative dentistry is comparable to and perhaps less than the cost of placing and replacing dental restorations. The early intervention concept is interesting as it may be easier to affect the caries-associated bacteria before their permanent colonization compared with later in life when the resident oral flora is firmly established.

Dental caries in young children has a multifactorial etiology; therefore preventive measures usually involve a combination of dietary counseling, oral hygiene, and fluoride application. None of these interventions specifically target Streptococcus mutans, the chief pathogen responsible for caries. Therefore, current methods of caries management which are limited to traditional preventive approaches in combination with restorative treatments have proved inadequate to control the disease. New methods of managing dental decay in the primary dentition need to be developed. An antibacterial agent that is effective and also acceptable to young children will be a useful supplement to current techniques for the prevention of caries. Chlorhexidine is the antimicrobial agent most familiar to dental professionals for prevention of dental caries in children. The need for frequent application of Chlorhexidine, and other side effects such as unpleasant taste and staining, has stimulated the search for alternatives that are more appropriate for young children.

“Triphala” is among the most common formulas used in Traditional Ayurvedic Medicine.

Composed of the fruits of three trees, Indian gooseberry Amalaki (Embilica officinalis), Bibhitaki (Terminalia beleria), and Haritaki (Terminalia chebula), Triphala is mentioned throughout the ancient literature of Ayurvedic medicine as a tonic, highly prized for its ability to regulate the process of digestion and elimination. Study done by Maurya et al[1] supports the use of Triphala for the cure of periodontal diseases. Certain shortcomings of this study were paucity of knowledge, short time interval, small sample size, no well-defined criteria for assessing periodontal disease, and no measurement of plaque and caries scores. Jagtap and Karkera[2] tested the efficacy of Triphala mouthwash in the inhibition of Streptococcus counts. However, this research lacked enough studies to support results. Thus, the effects of Triphala mouthwash on the dental health status have to be assessed.

In this context, a study was undertaken to ascertain the effects of a mouthwash prepared with Triphala on the oral health status and compare it with commercially available Chlorhexidine mouthwash.

Aims and Objectives

To evaluate clinically the efficacy of Triphala mouthwash on the dental plaque, gingival inflammation, and microbial counts (Streptococcus and lactobacilli counts) in school children.

To compare the effect of Triphala mouthwash with commercially available Chlorhexidine mouthwash.

To evaluate the feasibility of making it a commercial product.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted at the Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, in collaboration with the Department of Microbiology, Kasturba Medical College, MAHE. Approval from the institutional Ethics Committee was obtained before initiating the study.

Sample size

A total of 1431 students in the age group 8–12 years, belonging to classes forth to seventh, were the subjects for this study.

Materials used for recording indices

Mouth mirror, explorer, periodontal probe, tweezers, and chip syringe.

Materials used for the determination of salivary Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli

Sterile penicillin bottles for collection of stimulated saliva.

Agars to be used: Mitis salivarius agar (with bacitracin)

Lactobacillus MRS agar

A standard loop

Obtaining informed consent

Before the commencement of this study, an informed consent from the principal of the school and the parents of the students participating in this study was obtained. Children also gave assent to participate.

Selection of the students

The subjects were allocated to the specific treatment by block randomization. Children with similar socioeconomic status, dietary habits, oral hygiene methods, oral hygiene status, and KAP status were included. Further, only children who had a minimum of one to two established carious lesions were considered. The subjects were selected from residential schools.

Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice

The Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) of the subjects was determined using a questionnaire.

Group distribution

The subjects were divided into three groups:

Group I (n = 457): using Triphala mouthwash (0.6%)

Group II (n = 440): using Chlorhexidine mouthwash (0.1%) (positive control)

Group III (n = 412): using distilled water (negative control).

The schools were distributed in such a manner so that there was no intermingling within the students of different groups. It was a double-blind clinical trial.

Baseline assessment

Plaque scores were recorded using the methodology given by Silness and Loe[3] The gingivitis index was calculated according to the method given by Loe and Silness[4]

Microbiological analysis

Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli count was done in stimulated saliva. The subjects were asked to simulate chewing action with sterilized cotton rolls for 4 min. At the end of 4 min, the students were made to expectorate into sterile penicillin bottles. The stimulated saliva was then transported to the microbiology department within 30 min. A semi-quantitative that is four-quadrant streaking method was adopted (Sitges-Serra and Linares)[5] Using a standard loop, the saliva was streaked on Mitis salivarius agar with bacitracin (for Streptococcus mutans) and Lactobacillus MRS agar (for lactobacilli).

The growth in all the four quadrants was recorded. The colonies were identified based on colony morphology and gram staining. Growth in each quadrant was accorded the scores in CFU/ml. Thus,

<10,000 CFU/ml: three primary streaks in one quadrant;

25–50,000 CFU/ml: growth in one complete quadrant;

50–75,000 CFU/ml: growth in two complete quadrants;

75–100,000 CFU/ml: growth in three complete quadrants;

>100,000 CFU/ml: growth in four complete quadrants.

Preparation of mouthwashes

Triphala mouthwash was prepared in the pharmacy manufacturing center, Manipal, in the concentration of 0.6%, and it was then dispensed in 1-liter cans and delivered for use. Chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash (Proprietary name: Clohex, concentration 0.2%) was procured from the market and given to the pharmacy manufacturing center. It was then diluted and the final concentration of Chlorhexidine gluconate was 0.1%. This was dispensed in the 1-liter cans.

Both solutions were made of identical colors to eliminate bias. The bottles were then coded and then at the end of the study, the decoding was done.

For the Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus counts, Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney tests were applied for intragroup and intergroup comparison, respectively. All the tests were carried out in the SPSS software.

Administration of mouthwash

The teachers were educated and trained in the use of mouthwash so that the children, under the supervision of the teachers, could use the mouthwash. Each of the groups used the respective mouthwash, as a daily, supervised rinse after lunch in the afternoon. The children were advised not to eat or rinse for the next 30 min. They were instructed to carry home the mouthwash bottles on weekends and during vacations.

The Chlorhexidine mouthwash was used in concentration of 0.1% such that 10 ml was dispensed at one time. The mouthwash was swished in all quadrants of the mouth for a period of 2 min. An equal quantity of Triphala mouthwash and placebo (distilled water) was dispensed.

Follow-up

Plaque, gingivitis scores, and microbiological analysis were recorded at baseline 3, 6, and 9 months after baseline.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were subjected to statistical analysis. For intragroup comparison of plaque and gingival scores, the paired sample t-test was applied, while for the intergroup comparison Tukey's test was applied.

RESULTS

Attrition of the sample

There was attrition of the sample in all the three groups. The number of subjects at the end of the study was 457 in Group I, 440 in Group II, and 412 in Group III. The percentage of attrition in Groups I, II, and III was 7.67%, 7.36%, and 10.62%, respectively. The overall attrition of the entire sample was 8.52%.

Plaque and gingivitis scores

Mean plaque and gingivitis scores at baseline

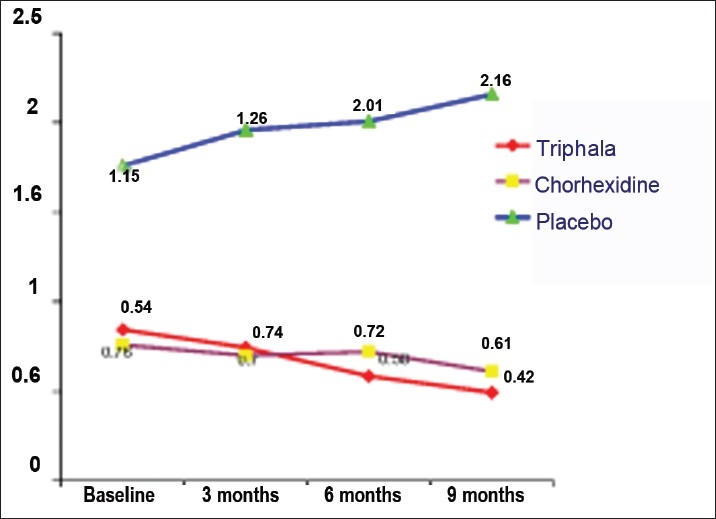

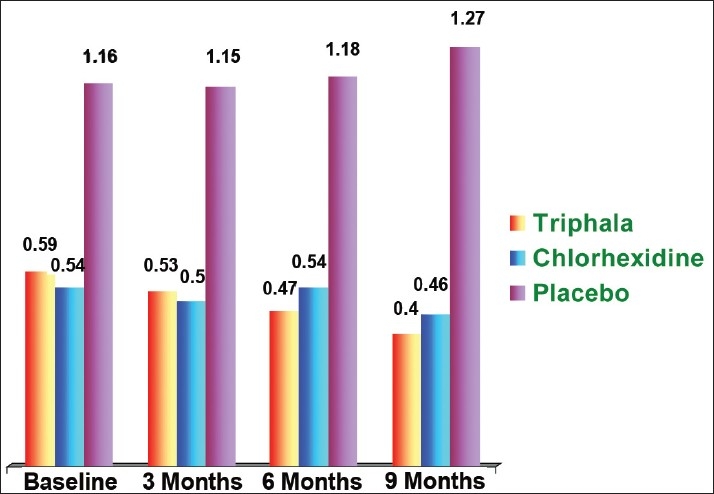

Mean plaque scores of Groups I, II, and III at the baseline were 0.84 ± 0.29, 0.76 ± 0.30, and 1.76 ± 0.24, respectively, while the mean gingivitis scores of Groups I, II, and III were 0.59 ± 0.73, 0.54 ± 0.22, and 1.16 ± 0.21 respectively [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Mean plaque scores

Figure 2.

Mean gingivitis scores

Mean plaque scores at various time intervals

-

Three months

The mean plaque scores of Group I (Triphala) and Group II (Chlorhexidine) at 3 months interval were 0.74 ± 0.25 and 0.70 ± 0.29, respectively. In the control group (distilled water), the plaque score was 1.96 ± 0.81.

-

Six months

The mean plaque scores of Groups I, II, and III at 6 months interval were 0.58 0.19, 0.72 ± 0.26, and 2.01 ± 0.84, respectively.

-

Nine months

The mean plaque scores at 9 months interval of Groups I, II, and III were 0.49 0.16, 0.61 ± 0.25, and 2.16 ± 2.50, respectively.

Mean gingivitis scores at various time intervals

-

Three months

The mean gingivitis scores after 3 months of mouthwash administration in Groups I, II, and III were 0.53 ±0.24, 0.50 ± 0.24, and 1.15 ± 0.43, respectively.

-

Six months

The mean gingivitis scores of Groups I, II, and III at 6 months interval were 0.47 ± 0.19, 0.54 ± 0.22, and 1.18 ± 0.55, respectively.

-

Nine months

The mean gingivitis scores at the conclusion of the study were 0.40 ± 0.16, 0.46 ± 0.20, and 1.27 ± 0.98 in Groups I, II, and III, respectively.

Microbiological analysis

Fifty students from each group were selected randomly for the microbiologic analysis. In these students, the stimulated saliva samples were collected, where Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus counts were tested.

Streptococcus mutans counts

Growth of Streptococcus mutans was checked by the semi-quantitative method (four-quadrant streaking).

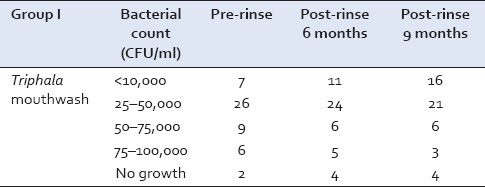

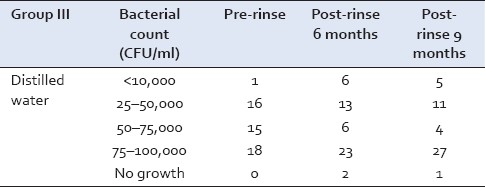

Group I

The Streptococcus mutans counts were recorded in 50 subjects at the baseline. Out of these, 26 samples showed growth in the lower range of 25–50,000 CFU/ml of saliva and 6 samples showed growth in the higher range of 75–100,000 CFU/ml. However, at the conclusion of this study, after 9 months, 21 samples showed growth of 25–50,000 CFU/ml and only 3 samples showed growth of 75–100,000 CFU/ml [Table 1].

Table 1.

Streptococcus mutans growth in Group I at baseline, 6 and 9 months

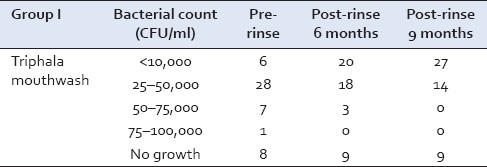

Group II

The Streptococcus mutans counts at the baseline in Chlorhexidine group were in the range of 75–100,000 CFU/ml in 21 samples and 12 samples showed growth in the range of 25–50,000 CFU/ml. After 9 months, 23 samples showed growth in the range of 25–50,000 CFU/ml and 11 samples showed growth in the range of 75–100,000 CFU/ml [Table 2].

Table 2.

Streptococcus mutans growth in Group II at baseline, 6, and 9 months

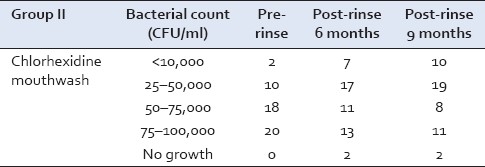

Group III

However, in Group III at the conclusion of the study, majority of the samples showed growth in the range of 75–100,000 CFU/ml [Table 3].

Table 3.

Streptococcus mutans growth in Group III at baseline, 6, and 9 months

Lactobacillus counts

Growth of Lactobacillus which was checked by the semi-quantitative method (four-quadrant streaking) for various groups was as follows:

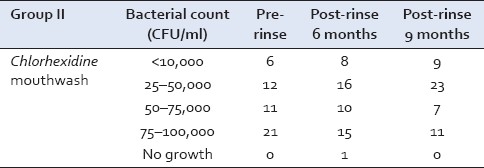

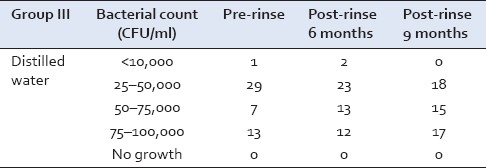

Group I

The Lactobacillus counts at the baseline in the children using Triphala mouthwash were in the range of 25–50,000 CFU/ml in 28 samples and 1 sample showed growth >75,000 CFU/ml. After 9 months, maximum number of 27 samples had growth <10,000 CFU/ml [Table 4].

Table 4.

Lactobacillus growth in Group I at baseline, 6, and 9 months

Group II

The Lactobacillus counts before starting the mouthwash (Chlorhexidine) were in the range of 75–100,000 CFU/ml in 20 samples and 25–50,000 CFU/ml in 10 samples. At the conclusion of this study, that is after 9 months of rinsing 11 samples growth in the range of 75–100,000 CFU/ml and 19 samples had growth of 25–50,000 CFU/ml [Table 5].

Table 5.

Lactobacillus growth in Group II at baseline, 6, and 9 months

Group III

In Group III, 18 samples showed growth in the range 25–50,000 CFU/ml and 17 samples showed growth in the range of 75–100,000 CFU/ml [Table 6].

Table 6.

Lactobacillus growth in Group III at baseline, 6, and 9 months

DISCUSSION

In this study, eight schools were chosen from areas around Manipal. A total of 1431 children having the same socioeconomic status and oral hygiene practice, in the age group of 8–12 years, were selected for this study. Children were selected mostly from the residential schools wherein same food was served for all children. Large sample size was selected anticipating the possible attrition of the sample due to varying cultural background and migration of few students to other schools.

There was an overall attrition of the sample by 8.52% at the end of this study. This attrition was because many students changed schools after completion of an annual session, which had fallen during the period of the study. The attrition percentage was not considered to be significant as study had a large sample size and was within the normal limits. Similarly, Lang et al[6] conducted a longitudinal study and found that majority of times attrition occurred due to family reasons where the parents changed the school of their child.

The division into groups was done in such a way that there was no intermingling of students from different groups. This was done to prevent any discussion among the students on the type and taste of the mouthwash they were using.

Students in Group I used Triphala in a concentration of 0.6%. Similar concentration was used in a study by Gupta et al,[7] wherein 0.6% Triphala was highly effective in preventing plaque accumulation and gingivitis. Chlorhexidine was used in a concentration of 0.1% in this study instead of the commonly prescribed 0.2% as advised by Segreto et al[8] . He concluded that 0.1% twice daily offers the same clinical benefits as a 0.2% Chlorhexidine solution. Moreover, 0.1% Chlorhexidine also helped in reducing the bitter taste and observed to be readily acceptable in children

Addy[9] too stated that 0.1% formulation produced less staining, particularly when diluted. Hence, in this study 0.1% concentration was used as the mouthwash had to be used for a longer period of time.

Group III served as the control group and was included in this study to rule out any effect, which could be due to the mechanical effect of rinsing.

The efficacy of the mouthwash was tested against plaque (Silness and Loe index),[3] gingivitis (Loe and Silness index),[4] Streptococcus, and the Lactobacillus counts (Sitges-Serra and Linares).[5] After these mouthwashes were administered, the indices were recorded at 3, 6, and 9 months intervals. These indices were used as they are simple and are mostly used in controlled clinical trials of preventive and therapeutic agents.

Children were instructed to rinse their mouth with 10 ml of prepared mouthwash in their respective groups for a period of 1 min after lunch. Similar amount and duration of mouthwash administration was followed in a study conducted by Axelsson and Lindhe.[10] They were then instructed not to rinse their mouth with water or drink anything for half an hour because the retention of Chlorhexidine in the oral cavity is dependent on a number of factors as is stated by Walton and Thompson,[11] and the food ingestion significantly decreased salivary Chlorhexidine.

Plaque

The students in Group I used the Triphala mouthwash (0.6%). The results in this group indicate that the plaque scores at all the recordings were lower than that at the baseline as seen in Figure 1. The plaque scores decreased progressively from baseline 0.84 ± 0.29 to 0.74 ± 0.25 at 3 months. This declining trend continued for the sixth month (0.58 ± 0.19) and the ninth month as well (0.49 ± 0.16). Comparison between the baseline and the ninth month was found to be highly significant (P = 0.001), suggesting that the mouth rinse has better results when used for a longer duration of time. This reduction in the plaque scores could be attributed to the antibacterial activity of Triphala, which has been shown in studies by Khorana et al,[12] Inamdar and Rajarama Rao,[13] and Maurya et al.[1] The students in Group II showed decline in plaque scores from baseline (0.76 ± 0.30) till the end of 3 months (0.70 ± 0.29) [Figure 1]. This reduction was found to be highly significant with a P-value of 0.001. This reducing trend continued till 6 months (0.72 ± 0.26) and 9 months intervals (0.61 ± 0.25) and was significant in all the intervals. The reduction was highly significant from baseline to 6 and 9 months, suggesting a continuous reduction in plaque scores. Gehlen et al,[14] also in their study on plaque regrowth concluded that 0.2% Chlorhexidine reduced the plaque scores significantly which is in accordance with the findings observed in this study.

In Group III, there was an increase in all the intervals from 1.76 ± 0.24 at baseline to 1.96 ± 0.81 at 3 months, 2.01 ± 0.84 at 6 months, and 2.16 ± 2.50 at 9 months as shown in Figure 1. This increase was found to be highly significant in all the intervals. Similar observation was noted in a study conducted by Vanka and Tandon,[15] where it was found that there was a significant increase in the plaque scores in all the intervals. Considering the fact that our study is a longitudinal study, the baseline values itself were higher in this group as they were carry forwarded to this study from the previously conducted study.[7]

An intergroup comparison done at 6 and 9 months showed that plaque scores in Groups I and II showed statistically significant difference (P = 0.001), thus suggesting the efficacy of Triphala over the Chlorhexidine over a long period of time. However, the plaque scores of both the Groups I and II were significantly different (P < 0.05) from Group III (control group), suggesting that the mechanical action of rinsing alone is not sufficient for the control of plaque.

Gingivitis

A clear cause and effect relationship exists between dental plaque and gingivitis (Loe et al).[16]

In Group I there was a reduction in the gingivitis scores from the baseline value of 0.59 ± 0.73 to 0.53 ± 0.24 at the end of 3 months which was not significant as the P-value was 0.193. However, at the end of sixth and ninth months intervals, significant reduction was noticed compared with the baseline with a P-value of 0.034 and 0.000.

Thus, it could be concluded that the Triphala mouthwash was capable of preventing gingivitis when used over a long period of time. Zaiba et al[17] reported that Emblica officinalis (one of the constituents of Triphala) helps to prevent bleeding gums and reduces inflammation. Group II [Figure 2] showed reduction in gingivitis scores from the baseline (0.54 ± 0.22) till the end of 3 months (0.50 0.24) which was highly significant (P = 0.001).

Thereafter, in this study, the gingival scores increased from 3 to 6 months and were comparable to the baseline at sixth months interval (0.54 ± 0.22). This increase can be attributed to the irregularity in the use of mouthwash. The probable explanation for such an increase could be that this period coincided with the examination of the students and during this period the subjects might not have strictly adhered to the instructions regarding the use of mouthwash.

Then from sixth month onward the gingival scores decreased significantly when compared with baseline till the conclusion of this study with a P-value of 0.001. Lucas and Lucas[18] stated that 0.12% Chlorhexidine mouth rinse can provide an important adjunct to the prevention and control of gingivitis.

In Group III an initial reduction was found till the end of third month (1.15 ± 0.43) when compared with the baseline (1.16 ± 0.21), and thereafter an increase in the gingival scores from the third month toward the conclusion of this study [Figure 2]. This increase in values again suggested that the mechanical action of rinsing alone was not sufficient to prevent the occurrence of gingivitis.

Intergroup comparison at 6months revealed a statistically significant difference between Group I and Group II (P = 0.012) and a highly significant difference (P = 0.001) between Group III compared with Groups I and II.

However, at 9 months Group I and II did not differ significantly (0.178), suggesting that both the mouthwashes have same long-term effect on gingival health. Thus, it could be suggested that the Triphala mouthwash was comparable to Chlorhexidine in maintaining the healthy status of the gingiva. Similar observation was noted in a study by Gupta et al.[7]

Microbiologic analysis

Effect on Streptococcus mutans

There was significant inhibitory effect of Triphala mouthwash (Group I) on Streptococcus mutans growth from baseline to the sixth and the ninth month (P = 0.001) intervals. This could be attributed to the antibacterial property of Triphala as stated by Khorana et al.[12]

Students in Group II using Chlorhexidine showed statistically significant reduction at sixth and the ninth month intervals as the P-value was 0.001. This is supported by the study of Emilson[19] where it was found that Chlorhexidine treatment reduces Streptococcus mutans counts for a period of 4–6 months.

In Group III (distilled water) the majority of the samples showed Streptococcus mutans growth in the range of 75–100,000 CFU/ml. This remained unchanged at the post-rinse, 9 months. However, the number of subjects falling in this category increased. This suggests that with mechanical rinsing there was a marginal increase in Streptococcus mutans growth which was non-significant. In a similar study conducted by Olmez et al,[20] it was found that when distilled water was used as a mouthwash in the control group, there was no significant reduction in the Streptococcus mutans counts as observed in this study [Tables 1–3].

Lactobacillus counts

In Group I, it was found that there was statistically significant reduction in Lactobacillus counts at 6 months and 9 months (P = 0.032, P = 0.001), respectively, when compared with baseline. This again could be ascribed to the antibacterial activity of Triphala (Khorana et al.[12]

In Group II (Chlorhexidine), significant reduction in Lactobacillus growth was noted at 9-month interval compared with the baseline; the P-value was 0.034. However, at 6 months reduction was non-significant (P = 0.113), comparing the scores between 6 and 9 months also showed a non-significant decrease. Study conducted by Emilson[19] showed that with the use of Chlorhexidine, little effect was seen on Lactobacillus growth. This is in accordance with this study.

In Group III (distilled water), no time interval showed any significant difference in Lactobacillus counts from baseline. Thus, distilled water had negligible effect on Lactobacillus growth [Tables 4–6].

CONCLUSIONS

The following conclusions were drawn from this study:

Group I, using Triphala (0.6%), and Group II, using Chlorhexidine (0.1%), showed a similar trend in preventing plaque formation. There was a progressive decrease in the plaque scores from the baseline to the end of 9 months.

Both Triphala and Chlorhexidine have shown similar effect on gingival health.

Both Group I (Triphala) and Group II (Chlorhexidine) showed similar inhibitory effect on microbial counts, except Lactobacillus where Triphala has shown better results than Chlorhexidine.

Effect of distilled water on oral health status indicated that simple mechanical rinsing with water is not adequate to show any positive results.

The results of this study showed that 0.6% Triphala and 0.1% Chlorhexidine have an inhibitory effect on plaque, gingivitis, and growth of Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus. Therefore, Ayurveda-based regimens are likely to replace Chlorhexidine soon as intense antimicrobial, palatable, and cost-effective preventive strategies. However, more scientific work needs to be carried out to prove the efficacy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research project was funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Indian Council of Medical Research

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maurya DK, Miltal N, Sharma KR, Nath G. Role of Triphala in management of periodontal disease. Anc Sci Life. 1997;17:120–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagtap AG, Karkera SG. Potential of the aqueous extract of Terminalia chebula as an anticaries agent. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;68:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in children, correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odont Scan. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy I: prevalence and severity. Acta Odont Scan. 1967;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sitges-Serra A, Linares J. Limitations of semi-quantitative method for catheter culture. J Clin Micro. 1988;26:1074–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.5.1074-1076.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang NP, Hotz P, Graf H, Geering AH, Saxer UP, Sturzenberger OP, et al. Effects of supervised Chlorhexidine mouthrinses in children: A longitudinal clinical trial. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:101–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1982.tb01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta K, Tandon S, Rao S, Malagi KJ. Effects of Triphala mouthwash on the oral health status. Malays Dent J. 2004;25:27–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segreto VA, Collins EM, Beiswanger BB. A comparison of mouthrinses containing two concentrations of Chlorhexidine. J Periodont Res. 1986;21(Suppl 16):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Addy M. Chlorhexidine compared with other locally delivered antimicrobials.A short review. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;13:957–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Axelsson P, Lindhe J. Efficacy of mouthrinses in inhibiting dental plaque and gingivitis in man. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:205–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walton JG, Thompson JW. Textbook of dental pharmacology and therapeutics. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford university Press; 1994. pp. 147–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khorana ML, Rajarama Rao MR, Siddiqui HH. Indian J Pharm. 1959;21:331. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inamdar MC, Rajarama Rao MR. Studies on the Pharmacology of Terminalia chebula Retz’ Department of chemical technology. Bombay: University of Bombay; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gehlen I, Netuschil L, Georg T, Reich E, Berg R, Katsaros C. The influence of a 0.2% Chlorhexidine mouthrinse on plaque regrowth in orthodontic patients. A randomized prospective study. Part II: Bacteriological parameters. J Orofac Orthop. 2000;61:138–48. doi: 10.1007/BF01300355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanka A, Tandon S. A controlled clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of neem mouthwash as compared to Chlorhexidine against plaque and gingivitis as well as Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus growth. Ind J Dent Res. 2001;12:133–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaiba IA, Beg AZ, Mahmood Z. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of E. officinalis, T. chebula and T. bellerica. Indian Vet Med J. 1999;23:299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucas GQ, Lucas ON. Preventive action of short-term and long-term Chlorhexidine rinses. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 1999;12:45–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emilson CG. Potential efficiency of Chlorhexidine against mutans streptococci and human dental caries. J Dent Res. 1994;73:628–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730031401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olmez A, Can H, Ayhan H. Effect of an alum-containing mouthrinse in children on plaque and salivary levels of selected oral microflora. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1998;22:335–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]