Sir,

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion, hydroxyl, hydrogen peroxide radical, and peroxynitrite participate in the process of inflammation in various tissues.[1] Excessively produced ROS can injure cellular biomolecules, such as nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, causing cellular and tissue damage, which in turn augments the state of inflammation.[2,3] In addition to their role in acute inflammation, ROS may also contribute to several chronic cutaneous inflammatory diseases, such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis.[4] Therefore, compounds of natural origin that have scavenging activities toward these radicals may be expected to have therapeutic potentials for several inflammatory diseases. Pterocarpus santalinus L. (Fabaceae) is commonly called as Red sandalwood (English). In Ayurvedic system of medicine in India, the plant is used traditionally as an antiseptic, wound healing agent and in antiacne treatment. A paste of the wood is used as a cooling external application for inflammations and headache. A decoction of fruit is used as an astringent tonic in chronic dysentery.[5,6] Based on its ethnomedicinal and traditional use, the plant was screened for analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities.

The woods of Pterocarpus santalinus L. were purchased from Yucca Enterprises, Mumbai and authenticated by Dr. B.D. Vashistha, Department of Botany, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra (Haryana, India). The woods were thoroughly cleaned, dried in the shade, and stored in an airtight container at 25 °C. Dried woods of the plant were coarsely powdered and 200 g of this powdered material was macerated with 500 ml methanol separately for 48 h. The Pterocarpus santalinus methanolic wood extract (PSMWE) was then filtered and distilled on a water bath. The last traces of the solvent were evaporated under reduced pressure in rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Model-4011). The yield of the methanolic extract was 1.8% (w/w). For pharmacological experiments, a weighed amount of the dried extract was suspended in 2% (v/v) aqueous Tween 80 solution. The preliminary phytochemical screening of PSMWE was carried out as per reported methods.[7]

The male Wistar rats weighing 180-200 g and Swiss albino mice weighing 25-30 g were purchased from Haryana Agriculture University, Hisar (Haryana, India). The animals were maintained under controlled environmental conditions (i.e., room temperature 25 ± 2°C, relative humidity 60%-70%), and allowed free access to food and water ad libitum. The animals were deprived of food for 24 h before the commencement of the experiment but allowed free access to water. All studies were carried out by using five animals in each group. Experimental protocols/procedures used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, India and conform to the guidelines of ‘Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision on Experiments on Animals’ [Reg. No. 562/02/a/CPCSEA].

The acute toxicity tests were performed according to OECD-423 guidelines.[8] Swiss mice (n = 5) of either sex selected by random sampling technique were employed in this study. The animals were fasted for 4 h with free access to water only. PSMWE was administered orally at a dose of 2 g/kg initially and mortality was observed for 3 days.

The rats were divided into five groups each consisting of five for screening of anti-inflammatory activity. The control group received only Tween 80 (2%, v/v) orally, the standard group received diclofenac sodium (50 mg/kg) i.p. and the test groups received PSMWE (at the doses of 100, 250, and 500 mg/kg) orally. The carrageenan-induced rat paw edema test was performed according to reported method.[9] The measures were determined at 0 h (before carrageenan injection), 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after drug treatment.

The analgesic activity of PSMWE was measured against chemical and thermal stimulus using acetic acid induced abdominal writhing test[10] and Eddy's hot plate method.[11] The antioxidant assay of PSMWE was determined using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging method.[12] All data were represented as mean ± S.E.M. and as percentage. Results were statistically evaluated using one way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's t-test. P ≤ 0.001 was considered significant.

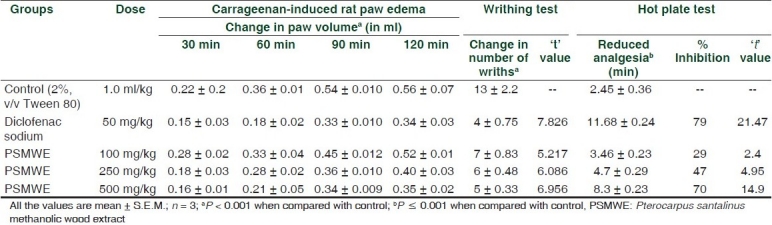

The methanolic wood extract was found to contain glycosides, essential oils, flavonoids and polyphenolic compounds. PSMWE did not produce any mortality even at the highest dose (2000 mg/kg, p.o.) employed. All the doses (100, 250, and 500 mg/kg, p.o.) of Pterocarpus santalinus methanolic wood extract were thus found to be non-toxic. The methanolic extract at 100, 250, and 500 mg/kg p.o. caused an inhibition on the Carrageenan-induced rat paw edema [Table 1]. The maximal inhibition in edema volume was observed at a dose of 500 mg/kg. The methanolic extract at 100, 250, and 500 mg/kg orally caused an inhibition on the writhing response induced by acetic acid [Table 1]. The maximal inhibition of the nociceptive response was achieved at a dose of 500 mg/kg.

Table 1.

Effect of PSMWE in Carrageenan induced rat paw edema, writhing test and hot-plate test

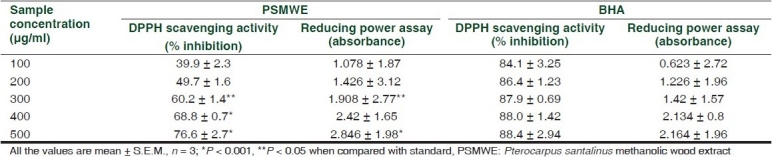

The wood extract, when given orally in doses of 100, 250, and 500 mg/kg, elicited a significant analgesic activity (P ≤ 0.001) in the hot plate as evidenced by increase in latency time in seconds [Table 1] as compared with vehicle control at the end of 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. The increase in latency time was dose dependent. For the measurements of the reducing ability, ‘Fe3+-Fe2+ transformation’ in the presence of PSMWE was found. The reducing capacity of a compound may serve as a significant indicator of its potential antioxidant activity. The reductive capabilities of extract were compared with BHA. The reducing power of PSMWE was found to increase with increasing concentrations (P < 0.001). DPPH radical was used as a substrate to evaluate the free radical scavenging activity of PSMWE. The scavenging effect of PSMWE on the DPPH radical was 76.6 ± 1.5 % (P < 0.001), at a concentration of 500 μg/ml as compared to the scavenging effects of BHA at 500 μg/ml of 88.4 ± 1.4 %, respectively [Table 2].

Table 2.

In vitro free radical scavenging effect of PSMWE

The results observed in the rat paw edema assay showed a significant inhibitory activity of the extract in carrageenan induced paw inflammation, at the doses of 100, 250, and 500 mg/kg administrated p.o. [Table 1]. Edema formation in paw occurs as a result of production of various inflammatory mediators like histamine, cyclooxygenase and arachidonic acid metabolites. Moreover, due to the role of reactive species in the inflammatory process and recent reports about the relation between periodontal disease/stomatitis and impaired antioxidant status, the scavenging effects of the PSMWE on reactive oxygen species could be considered important for the anti-inflammatory effect. Acetic acid-induced writhing model represents pain sensation by triggering localized inflammatory response. Such pain stimulus causes the release of free arachidonic acid from tissue phospholipid. The acetic acid induced writhing response is a sensitive procedure to evaluate peripherally acting analgesics. The response is thought to be mediated by peritoneal mast cells, acid sensing ion channels, and the prostaglandin pathways.

The hotplate method is considered good to examine compounds acting through opoid receptor; the extract increased mean basal latency which indicates that it may act via centrally mediated analgesic mechanism. The extract inhibited both mechanisms of pain, suggesting that the plant extract may act as a narcotic analgesic. The present results indicate the efficacy of PSMWE as an efficient therapeutic agent in acute anti-inflammatory conditions. The extract showed strong analgesic action in mice, by inhibiting the acetic acid-induced writhing and by increasing the latency period in the hot-plate test. These findings seem to, in part, justify the folkloric uses of this plant. The methanolic wood extract was screened for various phytochemical tests and found to contain glycosides, essential oils, flavonoids and polyphenolic compounds. Further, Polyphenolic compounds, like flavonoids, tannins and phenolic acids, commonly found in plants have been reported to have multiple biological effects, including antioxidant activity. Therefore, presence of flavonoids and polyphenolic compounds in the extract as evidenced by preliminary phytochemical screening suggests that these compounds might be responsible for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. There are also reports on the role of flavonoid, a powerful antioxidant, in analgesic activity primarily by targeting prostaglandins. Therefore, it can be assumed that cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitory activity together with antioxidant activity may reduce the production of free arachidonic acid from phospholipid or may inhibit the enzyme system responsible for the synthesis of prostaglandins and ultimately relive pain-sensation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trenam CW, Blake DR, Morris CJ. Skin inflammation: Reactive oxygen species and the role of iron. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:675–82. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12613740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cochrane CG. Cellular injury by oxidants. Am J Med. 1991;91:S23–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90280-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong SG, Kang BJ, Kang SM, Cho DW. Antioxidative effects of traditional Korean herbal medicines on APPH-induced oxidative damage. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2001;10:183–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharkey P, Eedy DJ, Burrows D, McCaigue MD, Bell AL. A possible role for superoxide production in the pathogenesis of contact dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:156–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadkarni AK, Nadkarni KM. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Bombay, India: Popular Prakashan; 1996. Indian Materia Medica; pp. 1025–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anonymous. The Wealth of India: A dictionary of raw materials and Industrial products, 1st supplement series (Raw Materials) Vol. 4. New Delhi, India: NISCAIR, CSIR; 2003. p. 422. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khandelwal KR. Pune, India: Nirali Prakashan; 2007. Practical Pharmacognosy; pp. 149–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ecobichon DJ. New York: CRC Press; 1997. The Basis of Toxicology Testing; pp. 43–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter CA, Risley EA, Nuss GW. Carrageenan induced edema in hind paw of the rat as an assay for antiinflammatory drugs. Exp Biol Med. 1962;111:544–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collier HD, Dinnin LC, Johnson CA, Schneider S. The abdominal pain response and its suppression by analgesic drugs in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 1968;32:295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1968.tb00973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eddy NB, Leimbach D. Systemic analgesics II Diethylbutenyl and diethienylbutyl amines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1953;107:385–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar S, Kumar D, Manjusha, Saroha K, Singh N, Vashishta B. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging potential of Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. methanolic fruit extract. Acta Pharm. 2008;58:215–20. doi: 10.2478/v10007-008-0008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]