Abstract

In response to increasing obesity, diabetes, and food-related contributions to climate change, many individuals and organizations are mobilizing to advocate for healthier and more just local and national food policies and systems. In this report, we describe and analyze the food movement in New York City, examine tensions within it, and consider its potential role in improving health and nutrition. We conclude by suggesting that public health professionals can amplify the health effects of such movements by creating opportunities for dialog with movement participants, providing resources such as policy-relevant scientific evidence, documenting problems and evaluating policies, and offering technical, political, and organizational development expertise.

Keywords: Food environment, Social movements, Food policy, New York City

Like other cities around the world, New York faces problems of both high rates of food-related health conditions such as obesity and diabetes and persistent hunger and food insecurity. In addition, growing recognition of the contribution of current food practices to global climate change has led to calls for more sustainable food environments. In response, many individuals and organizations have mobilized to advocate for healthier, more just local, regional, and national food policies and systems. In this essay, we profile the food movement in New York City, consider its potential for improving health and nutrition, and suggest ways that public health professionals can help to amplify the health effects of such movements. We focus on New York City because of its rich diversity of food activism, the magnitude of its diet-related and hunger-related problems, and its history as a focal point for urban health problems and a cradle of public health innovation.

Social Movements and Public Health

A social movement has been defined as a “sustained organized public effort making claims on target authorities” that uses mainstream and unconventional political strategies to achieve its aims.1 Most social movements include heterogeneous social forces and advocate sometimes conflicting strategies to solve the problems they identify.2 In public health, social movements have contributed to improved worker health and safety, better housing, better health care, more services for people with HIV infection, stronger oversight of the tobacco industry, and reduced stigma against people with various health conditions.3–8 By riding the waves of social movements, health activists have often achieved more lasting changes than by working alone.

Social movement scholars have proposed criteria to assess whether a social mobilization meets the threshold for a movement. These include the presence of articulated grievances, policy goals, access to human and financial resources, sustained activities to meet these goals, and leaders and organizations.9,10 Others emphasize the importance of participants with a shared worldview and identity.11 Duster observes that “no movement is as coherent and integrated as it seems from afar” nor as “incoherent and fractured as it seems from up close.”12 Considering the full trajectory and lifespan of movements is more useful than a binary view in which a social movement is categorically labeled as either a movement or not a movement.

Methods

This report on the New York City food movement (NYCfm) is based on three sources. First, we conducted a selective review of scholarly, government, nonprofit, and activist reports on food issues and food activism in New York City in the last 10 years (2001–2010). These included major reports on food in New York City,13–15 transcripts or statements from the City Council and state legislative sessions as well as testimony presented at New York City hearings organized by the New York State Food Policy Council in 2009 and 2010. Second, we convened a meeting in June 2010 with about 35 policy makers, advocates, and researchers to assess the accomplishments and limitations of the NYCfm and consider future directions (participants identified in the “Acknowledgments” section) and prepared a detailed written summary of the session; we surveyed participants after the meeting about their reflections on the meeting and asked several to review drafts of this report. Our analyses are based on a systematic review of these documents. Unless otherwise noted, quotations are from meeting participants. Finally, we draw on our own experiences as participants and researchers in the NYCfm and other social movements to help frame our findings.

Food Activism in New York City

Recent scholarship on food activism presents a heterogeneous view of a food movement, emphasizing its roots on both social justice and cultural alternatives to mainstream food practices.16–19 Journalist and food activist Michael Pollan has labeled the movement a “lumpy tent”12 that includes:

school lunch reform; the campaign for animal rights and welfare; the campaign against genetically modified crops; the rise of organic and locally produced food; efforts to combat obesity and type 2 diabetes; “food sovereignty” (the principle that nations should be allowed to decide their agricultural policies rather than submit to free trade regimes); farm bill reform; food safety regulation; farmland preservation; student organizing around food issues on campus; efforts to promote urban agriculture and ensure that communities have access to healthy food; initiatives to create gardens and cooking classes in schools; farm worker rights; nutrition labeling; feedlot pollution; and the various efforts to regulate food ingredients and marketing, especially to kids.

New York City’s food movement is similarly diverse. It includes parents who want healthier school food for their children; chefs trying to prepare healthier and more local foods; church goers for whom food charity and justice manifest their faith; immigrants trying to sustain familiar, sometimes healthier food practices; food coop members longing for community as well as fresh food; food store workers wanting to earn a living wage while making healthy and affordable food more available; residents of the city’s poor neighborhoods who want better food choices in their communities; staff and volunteers at 1,200 food pantries and soup kitchens concerned about food insecurity; health professionals and researchers worried about epidemics of diabetes and obesity and the growing burden of food-related chronic diseases; elected officials, agency staff, and policy makers who want to seize opportunities to improve food; and gardeners and farmers who like to get their hands in the dirt and to eat the food they and their neighbors grow. These disparate individuals and the organizations they influence constitute an amalgam of forces determined to change the city’s food environments and food choices. Some are connected to regional, statewide, national, and international efforts to change food policies.

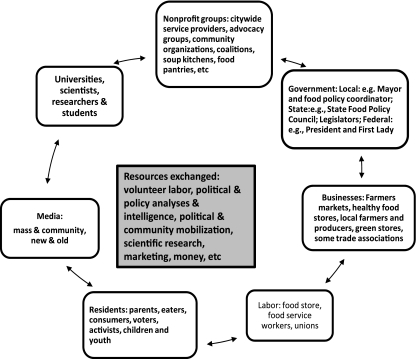

These constituencies inhabit numerous social spaces and exchange a variety of resources, illustrated schematically in Figure 1. Within each sector and across sectors, there are also tensions and power dynamics at play. For instance, in recent decades, in New York City and elsewhere, the already diverse nonprofit sector has expanded and sometimes taken over responsibilities previously conducted by government. The business sector includes both food-related businesses that are considered partners in the movement through their production and promotion of healthier foods, as shown in Figure 1, and others that are targets or opponents of the movement, thus not included in the figure. Similarly, government officials who support the goals of the movement are viewed as participants while others may oppose it.

FIGURE 1.

Organizational overview of New York City food movement.

Table 1 lists several organizations viewed as part of the NYCfm, illustrating the diversity of civic organizations involved in changing food environments in New York City. These groups provide a critical resource base for the NYCfm, providing human, social, political, and financial capital needed to advance its agenda.20

Table 1.

Selected representative civic organizations involved in New York City’s food movement

| Organization | Mission and activities | Date started |

|---|---|---|

| Added Value | Nonprofit organization promoting sustainable development of Red Hook, Brooklyn by nurturing a new generation of young leaders; creates opportunities for the youth of South Brooklyn to expand knowledge base, develop new skills, and positively engage with community through operation of a socially responsible urban farming enterprise | 2000 |

| Brooklyn Food Coalition | Grassroots partnership of groups and individuals striving to give effective voice to all who live or work in Brooklyn and seek to achieve a just and sustainable system for tasty, healthy, and affordable food; activities include research and organizing, educating parents about school food, producing workers’ rights newsletter, maintaining anti-racism committee, raising awareness about farm bill, and other food-related policies | 2009 |

| Brooklyn Rescue Mission | Grassroots organization devoted to growing local, organic food and distributing it to members of the surrounding communities who are largely people of color while raising awareness of the importance of food | 2002 |

| City Harvest | Nonprofit organization works to end hunger in communities in New York City through food rescue and distribution, education, advocacy, and other practical solutions; convened New York City coalition to advocate for reauthorization of Child Nutrition Act | 1982 |

| Just Food | Nonprofit organization unites local farms and city residents of all economic backgrounds to improve access to fresh, seasonal, sustainably grown food. Activities include providing technical assistance CSA programs, community food education, and organizing for food justice | 1995 |

| New York City Coalition Against Hunger | Nonprofit organization coordinating the activities of the emergency food providers in the city and engaging in advocacy and legislative efforts; activities include operating the Emergency Food Action Center, policy research and development, and conducting the Annual Survey on Hunger in New York City | 1983 |

| New York City Community Garden Coalition | Membership organization promoting preservation, creation, and empowerment of community gardens through education, advocacy, and grassroots organizing | 1996 |

| New York City Food and Fitness Partnership | Foundation-funded coalition engaging communities in creating equitable access to healthy, quality, affordable foods and opportunities for active living, starting in neighborhoods with highest need | 2007 |

| Food Systems Network NYC | Membership organization working toward universal access to nourishing, affordable food; activities include holding monthly open networking meetings, maintaining website with information about relevant public policy, and outreach activities | 2004 |

| Park Slope Food Cooperative | Food cooperative with 12,000 members; seeks to make food available, to create a community, to support establishment of coops in other neighborhoods, and to contribute to healthier food environments | 1973 |

| United Food and Commercial Workers—NYC local | Local branch of a national union that supports food workers in New York City and advocates for fair policies affecting them | 1979 |

| West Harlem Environmental Action (WE ACT) | Community activist organization working to build healthy communities by assuring that people of color and/or low income participate meaningfully in creation of sound and fair environmental health and protection policies and practices; activities include action and advocacy around clean air, affordable and equitable transit, sustainable land use, healthy indoor environment, and good food in schools | 1988 |

CSA community-supported agriculture

Goals, Tensions, and Challenges within New York City’s Food Movement

Table 2 lists some common goals of participants in the NYCfm, derived from a discussion with participants at the June meeting. While most participants share these goals, they do not necessarily agree on priorities and strategies. These broad visionary goals constitute a yardstick against which to assess accomplishments and limitations.

Table 2.

Some common goals identified by participants in the New York City food movement

| 1. Eliminate hunger and food insecurity in New York |

| 2. End disparities in access to healthy food by making healthy food more available and affordable throughout the city |

| 3. Restrict promotion and availability of unhealthy food |

| 4. Eliminate socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in food-related health conditions such as obesity and diabetes |

| 5. Improve school and other institutional food |

| 6. Increase sustainable production and access to food grown in New York City and its region |

| 7. Ensure that food workforce earns livable wages and has safe working conditions |

| 8. Expand alternatives to a food system that emphasizes processed and unhealthy foods |

| 9. Improve nutrition and food knowledge and skills |

| 10. Level political playing field so more New Yorkers can participate in making food policy |

Like any movement, members of the NYCfm have tensions and conflicts as well as varying levels of political and financial power. Here, we examine their sources and consequences.

Hunger versus Obesity Social reformers and antipoverty groups have long worked to reduce hunger in New York City. More than 75 years ago, nonprofit groups mobilized to feed thousands of hungry New York City residents during the Great Depression.21 More recently, policy makers, media, and health professionals have turned their attention to obesity, arguing that dramatic increases in obesity rates and links to chronic diseases such as diabetes make fighting obesity a priority.How to address these problems has sometimes proven divisive. Antihunger activists stress the social causes of hunger and food insecurity and look to government rather than individual solutions. Sometimes they partner with the food industry to achieve common goals, e.g., expansion of the Food Stamp program. They see food insecurity as linked to poverty and income inequality, claiming that only by reducing these deeper ills can the city eliminate hunger. Obesity activists are divided in allocating individual versus social responsibility, responding in part to the mainstream discourse on parental responsibility for childhood obesity.22 Some activists see links between food insecurity and obesity,23 arguing that food-insecure people are driven to consume inexpensive, high calorie, low nutrient foods. In this view, policies are needed to make healthier food more affordable to the poor. Some anti-obesity activists discourage partnerships with the food industry.This disagreement has played out in the debate on a proposed tax on sweetened beverages. Many health professionals support the tax to discourage consumption of sweetened beverages, a product associated with obesity especially among the poor, who have higher rates of obesity, by creating incentives for consuming healthier beverages.24 Opponents, including hunger activists and organizations (and the soda industry), say the tax unfairly targets the poor who have fewer choices and question whether it would achieve its aims if consumers purchase other high calorie nontaxed products.

Community Change versus Policy Change Another debate involves the balance between alternative neighborhood food distribution systems—urban agricultural projects, farmers markets, food coops—versus policy changes such as reducing federal subsidies for unhealthy foods, reducing barriers to enrollment in the Food Stamps program (now called SNAP), and improving school food. Proponents of the community approach claim success in creating new models for food distribution that engage new constituencies and bypass bureaucracies while critics note that these experiments reach only a fraction of the population and miss deeper causes of inequitable access to healthy food. While both approaches are needed, activists differ on the appropriate balance.

Supermarket Subsidies In 2009, New York City began offering incentives to supermarkets to locate in poor neighborhoods via a program called Food Retail Expansion to Support Health (FRESH).25 Some activists supported this effort, arguing it improves access to healthy food and helps reverse the flight of supermarkets from inner cities. Others claim that it fails to address supermarket promotion of unhealthy foods and lack of fresh foods, and that it risks gentrifying lower-income neighborhoods.26 “FRESH is a subsidy for supermarket chains, not poor people,” noted one community activist.

Cultural Change versus Political Change Some people join the food movement to change policies while others seek community, a different relationship to food, and the joy of growing and eating healthy, tasty food with friends and family. As one Brooklyn food activist explained, “Today many New Yorkers are hungry for connections to their community and for some, the food movement fills that need.” Most in the movement appreciate the value of these two motivations but often emphasize one or the other. Creating organizations, events, and a movement culture that speak both to the longing for community and the desire to have an impact on policy is challenging and can impede building broader coalitions.

Taking on Food Industry Food activists disagree about the priorities of increasing access to healthier food versus reducing the promotion and availability of unhealthy foods. Supporters of the former see a more positive approach, suited to mobilizing communities without incurring food industry opposition. Advocates of taking on the food industry suggest “if New York City and the nation are to succeed in reversing the epidemics of obesity and diabetes that threaten our city, we need to challenge the food industry’s right to pursue profit at the expense of public health.”27

Role of Municipal Government Food justice advocates also disagree about the role of the municipal government in the food movement. On the one hand, the mayor has played a leading role in initiating healthier food policy; without his leadership, the issue might not have been as high on the policy agenda nor attracted support from elected officials.28 On the other, with few exceptions, a top–down approach to policy has missed an opportunity to create grassroots constituencies for food change, making the transformative changes needed to improve population health more difficult.

Missing Voices While the NYCfm’s many “threads of advocacy”12 connect to all New Yorkers, not all residents have been able to participate equally in food-related activism. Lower-income residents and people of color are less visible among movement participants, raising questions about who speaks for the movement. Some activists fear that overrepresentation of white middle class activists hampers the effectiveness of a food justice movement. “If people of color and poor people are not leading the food movement,” explained one environmental justice activist, “then once again our needs will be overlooked.”Movements resolve these issues by deciding which policy proposals to support and oppose, what strategies to use, what coalitions to join, and whom to select as leaders, a process that can be simultaneously rational, deliberate, emotional, and chaotic. Such debates are the way movements forge common identities and resolve conflicts in practice. Still, divided movements have less political clout than unified ones and spend more time debating than changing policies. Some believe such debates should be avoided. While these two views are not mutually exclusive, how to resolve them is a key challenge for the NYCfm.

Recent Food Accomplishments in New York City

In the last 5 years (2006–2010), much progress has been made in changing food and food systems in New York City, including changes in policy, creation of new programs, engagement of new voices, and more favorable media coverage of food issues. Table 3 provides some examples of these changes. While not all participants in the NYCfm agree that all of these changes are victories, most feel that the majority of these changes represent important progress.

Table 3.

Recent changes in food policies and environments in New York City

| Category | Examples | Dates |

|---|---|---|

| Changes in policy | Incentives for new supermarkets to locate in poor neighborhoods (FRESH) | 2009 |

| New healthy food procurement guidelines for city agencies | 2008 | |

| Ban on trans fat in commercial food outlets | 2008 | |

| Requirement for calorie labeling in chain restaurants | 2008 | |

| New programs and services | Initiative to increase healthy foods at bodegas | 2005 |

| Expansion of farmers markets (doubled to 120 markets) | 2005–2010 | |

| Expansion of Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) access at farmer’s markets | 2005–2010 | |

| Establishment of Green Carts program to sell fruits and vegetables in poor neighborhoods | 2009 | |

| Improvements in New York City school food program | 2003–2010 | |

| Increase from one CSA drop-off point to 100 | 1995–2010 | |

| New voices and policy processes | Appointment of food policy coordinator in Mayor’s Office | 2007 |

| Creation of New York State Food Policy Council | 2008–2010 | |

| Public forums on food policy sponsored by elected officials | 2009 | |

| Brooklyn Food Coalition organizes Brooklyn Food Summit (3,300 people attend) | 2009 | |

| Media coverage | Media coverage of New-York-City—based lawsuit against McDonalds for contribution to child obesity | 2002–2010 |

| Media coverage of debates on calorie labeling | 2007–2009 | |

| Ad campaign against sweetened beverages | 2008–2009 | |

| Coverage of political debates on soda tax | 2009–2010 |

CSA community-supported agriculture

Can the changes in Table 3 be attributed to the activities of the NYCfm? Scholars of the evaluation of advocacy suggest several strategies for assessing its impact.29,30 While a detailed analysis of specific changes attributable to the NYCfm is beyond this report’s scope, many listed changes are goals of the NYCfm and its constituents, and these groups have worked to achieve these goals. Knowledgeable observers, including policy makers and advocates, attribute at least some of the changes to their activities. In many cases where specific policy changes were advanced by public agencies, advocates helped to craft the proposal and mobilize support. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the NYCfm contributed to these outcomes.

For example, activists played a key role in the legislative approvals of the Green Carts program and calorie posting at chain restaurants. Green Carts were opposed by local grocers, who feared loss of market share, and most sectors of the food industry actively opposed calorie labeling. Some legislators rejected lobbyists’ arguments because they received calls, visits, and letters from activists who countered these arguments. In Governing New York City, Sayre and Kauffman describe New York City’s pluralist government, in which various groups compete and cooperate, forming and dissolving alliances on specific issues.31 When the city’s powerful interests are divided, a social movement can have decisive influence in passing policies that might have languished in another environment.

With calorie labeling, the recent proliferation of these requirements by cities and counties was a key factor in the inclusion of a federal calorie labeling requirement in the new national health reform law. Because New York City was the first major locality with this requirement, it is reasonable to assert that the NYCfm has already made an impact on federal policy.32

What Has Not Yet Been Achieved?

Typically, movements achieve some goals and fail to accomplish others. An analysis of failures illustrates a movement’s strengths and weaknesses and its stage of development. Policy proposals not implemented by the end of 2010 include taxing sweetened beverages, using zoning laws to reduce the density of fast food outlets, and protecting funding for food-related services from budget cuts during recent government fiscal crises. The soda tax failed in 2009 and 2010 because of aggressive lobbying by the soda industry, and its opponents’ success in framing the controversy as a tax rather than a health issue. Supporters failed to persuade policymakers of the argument that federal subsidies for sugar and corn, key ingredients for soda, offered an unfair advantage to producers of unhealthy products.33,34 The 2006 zoning proposal failed in part because of technical barriers to amending New York City’s zoning rules and in part because proponents were unable to mobilize support to counter industry opposition.35

These examples show that even modest reforms challenging the status quo face formidable opposition. The NYCfm has had trouble overcoming opponents such as the soda industry, fast food chains, and fiscal conservatives. This indicates a need for more coherent and focused advocacy and broader coalitions.

Food Movement Contributions to Population Health

To what extent has the NYCfm demonstrated a potential to contribute to the health of New York City’s population? First, recent food advocacy has helped reframe public dialog on the food system. By calling attention to school food policies, regulation of food advertising to children, city food procurement, supermarket locations and more, advocates show that food choices are shaped by public as well as individual and family decisions. This dialog helps activists and policy makers move from America’s first language of individualism to the second language of solidarity and community responsibility, a terrain more favorable for developing healthy public policies.36 Food advocacy provides an avenue for citizens to involve themselves and demonstrate concern.

Also, the NYCfm has moved food policy higher on the city’s policy agenda and convinced officials to make improved food policy a priority. Concrete policy proposals—e.g., zoning restrictions on fast food outlets, a sweetened beverage tax, purchasing locally-grown foods for schools—are on the table. The NYCfm has moved food issues into the three streams that political scientist Kingdon argues are essential for policy change: the problem, policy, and political streams.37

Second, the NYCfm victories have widened food choices for New Yorkers, including low-income residents, potentially contributing to reduced food-related health disparities. Green Carts now sell fruits and vegetables in poor neighborhoods, food served in 1,500 public schools has improved, and many farmers markets now accept SNAP.

Third, the NYCfm has linked issues such as reducing food insecurity, preventing obesity, improving school food, creating a more sustainable food system, addressing environmental consequences of food practices, and eliminating health disparities. For public health officials and other policy makers, it can be difficult to initiate policy change on discrete issues simultaneously. When issues become linked, supported by diverse constituencies, based on a common goal, multiple proposals can create synergy rather than competition. As one health care reform advocate participating in the June meeting explained, “To realize the goals of national health reform and to reduce the burden of chronic disease, we need to reform our food system. Our slogan ought to be fix food first.” Meaningful improvements in population health require multiple actions, and public health professionals can use the linkages that the NYCfm has created to accelerate change.

Finally, the NYCfm has brought new voices into the policy arena. In 2009, when the New York State Food Council scheduled daytime hearings in a downtown Manhattan site, Harlem food activists and others objected, leading the council to add an evening session in Harlem. Just as the environmental justice movement expanded environmentalism from a white, conservation-oriented movement to an urban, low-income, African-American, Latino, and Native American social force,38 so too has the NYCfm expanded its range of concerns. These diverse constituencies can achieve higher levels of mobilization and advocacy leading to more health-enhancing policy change.

In summary, both national health objectives (e.g., Healthy People 2010)39 and local ones (e.g., Take Care NYC 2012)40 identify changes in food environments, diets, and food-related services as contributors to achieving improved health, reducing chronic disease, and promoting population well-being. By contributing to the changes in food-related consciousness, behaviors, services, and policies, the NYCfm has advanced these public health goals.

Next Steps for the Food Movement in New York City and Elsewhere

Current food activism in New York City is best regarded as an “emerging” food movement. This emerging movement has shared policy goals, a common resource base, and a trajectory of growth and development. To amplify its impact, the NYCfm needs publicly identifiable leaders, a well-known, coherent policy agenda, and deep roots in vulnerable communities, traits that characterized the civil rights, women’s, and HIV movements. If the public health contributions of earlier movements are a guide, then moving the NYCfm—and local movements in other cities—to a more developed stage can improve a city’s food-related health status.

How can public health professionals contribute to this? First, they can create opportunities for dialog with food movement participants. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has strengthened food-related public policy (e.g., Green Carts, calorie labeling, food procurement guidelines, etc.). While the department solicits public support for these policies, in its eagerness to achieve change within election and budget cycles, it has done less well listening to community concerns or supporting local leadership development. Savvy public health leaders listen to their constituents and encourage rather than stifle public debate.41

Second, public health professionals can support the NYCfm and similar movements by providing the resources a movement needs to succeed. This includes credible scientific evidence documenting problems and enumerating the health and economic benefits of policy proposals. Many organizations listed in Table 3 turn to public health officials and researchers for this evidence, enabling them to win over policy makers and disarm opponents. Universities and public health agencies can help activists analyze victories and defeats, plan future strategies, and step back from the day-to-day fray to consider the broader vision.

Third, public health professionals can help develop the organizations and leaders needed to take the NYCfm—and its counterparts across the nation—to the next stage. Organizations need technical, political, and development expertise. Food movement leaders need scientific skills to weigh evidence, communication skills to persuade policy makers, and organizational skills to plan, lead, and organize. Some public health professionals and organizations can provide resources and skills, strengthening the movement by bringing underrepresented groups into the arena.

Fourth, health professionals can evaluate policy changes won by activists, documenting benefits and identifying limitations. By providing feedback, timed to influence policy questions and speaking to policy maker concerns, evaluators can help the NYCfm consolidate victories and benefit from windows of opportunity.

Like other social movements, the NYCfm engages in substantive and symbolic actions. Green Carts, urban farms, and the use of SNAP at farmers markets, all policy changes achieved in part by activism, put healthier food in the hands of real people and represent an alternative vision to mainstream food distribution. It is too soon to know whether New York City’s food system reforms have changed New Yorkers’ diets enough to reduce food insecurity or obesity. Whether these steps signal deeper or mostly symbolic transformations remains to be seen. That will depend on developments in the national food movement as well as the success of activists in linking local, national, and global issues, and in bringing populations most harmed by our current food policies and system into the movement.

Conclusion

The current food activism in New York City is an “emerging food movement” with shared policy goals, a common resource base, and a trajectory of growth and development. We acknowledge the considerable heterogeneity in the NYCfm and its lack of coherent, stable, and widely accepted leadership. Only future events will determine whether this mobilization becomes a full-fledged and enduring social movement. The public health community has recognized that food and food policies are major influences on health and health disparities. Public pressure has triggered modest changes in food environments though not yet in food-related health outcomes. Public health history suggests that strong movements can play an essential role in achieving the transformation necessary to make healthy and affordable food available to all.

Acknowledgments

We thank the individuals listed below who participated in the June 2010 workshop at Hunter College on the NYCfm or suggested changes in drafts of this paper. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of our institutions or the participants in the workshop.

Agnes Molnar, Aine Duggan, Alexandra Hanson, Alison Cohen, Ana Garcia, Andrew Rundle, Arlene Spark, Benjamin Thomases, Christine Yu, Dennis Rivera, Devanie Jackson, Gail Gordon, Isabel Contento, Jan Poppendieck, Javier Lopez, Jenifer Clapp, Joe Holtz, Jon Deutsch, Kathy Goldman, Kim Libman, Kristen Mancinelli, Lauren Dinour, Monica Gagnon, Mark Dunlea, Melissa Cebollero, Mo Kinberg, Nadia Johnson, Nancy Romer, Peggy Shepard, Robert Jackson, Sabrina Baronberg, Sarita Daftary, Tom Angotti, and Triada Stampas.

References

- 1.Tilly C. Social Movements, 1768–2004. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porta D, Diani M. Social Movement: An Introduction. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szreter S. Rethinking McKeown: the relationship between public health and social change. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):722–725. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown P, Zavestoski S. Social movements in health: an introduction. Sociol Health Illn. 2004;26(6):679–694. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-9889.2004.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munch S. The women’s health movement: making policy, 1970–1995. Soc Work Health Care. 2006;43(1):17–32. doi: 10.1300/J010v43n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathanson CA. Social movements as catalysts for policy change: the case of smoking and guns. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1999;24(3):421–488. doi: 10.1215/03616878-24-3-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keefe RH, Lane SD, Swarts HJ. From the bottom up: tracing the impact of four health-based social movements on health and social policies. J Health Soc Policy. 2006;21(3):55–69. doi: 10.1300/J045v21n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCally M. Medical activism and environmental health. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2002;584:145–158. doi: 10.1177/0002716202584001011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diani M. The concept of social movement. Sociol Rev. 1992;40:1–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.1992.tb02943.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy JD, Zald MN. The enduring vitality of the resource mobilization theory of social movements. In: Turner JH, McCarthy JD, editors. Handbook of Sociological Theory. New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 535–565. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RH. The cultural contexts of collective action: constraints, opportunities, and the symbolic life of social movements. In: Snow DA, Soule SA, Kriesi H, editors. The Blackwell companion to social movements. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2004. pp. 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollan M. Food movement rising. New York Review of Books. 2010; 57(10): 31–33. [PubMed]

- 13.Manhattan Borough President. Food New York City: a blueprint for a sustainable food system. http://www.mbpo.org/uploads/foodnyc.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2011.

- 14.Quinn C. Food Works: A Vision to Improve NYC’s Food System. New York, NY: The New York City Council; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Food and Commercial Workers. Building blocks policy platform. http://buildingblocksproject.org/page/policy-platform. Accessed 7 Mar 2011.

- 16.Levkoe C. Learning democracy through food justice movements. Agric Human Values. 2006;23:89. doi: 10.1007/s10460-005-5871-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wekerle GR. Food justice movements: policy, planning, and networks. J Plan Educ Res. 2004;23:378. doi: 10.1177/0739456X04264886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nestle M. Reading the food social movement. World Lit Today. 2009;83(1):37–39. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlieb R, Josji A. Food justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards B, McCarthy JD. Resources and social movement mobilization. In: Snow DA, Soule SA, Kriesi H, editors. The Blackwell companion to social movements. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2004. pp. 116–152. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burlingham CC. The city’s huge relief battle and the plans for fighting it. New York Times October 23, 1932: XX3.

- 22.Pocock M, Trivedi D, Wills W, Bunn F, Magnusson J. Parental perceptions regarding healthy behaviours for preventing overweight and obesity in young children: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2010;11(5):338–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drewnowski A, Specter SE. Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(1):6–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brownell KD, Frieden TR. Ounces of prevention—the public policy case for taxes on sugared beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(18): 1805–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Cardwell D. A plan to add supermarkets to poor areas, with healthy results. New York Times. September 23, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/24/nyregion/24super.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2011.

- 26.Angotti T. Food deserts could bloom if City Hall helps. Gotham Gazette. January 2010. http://www.gothamgazette.com/article/landuse/20100128/12/3166. Accessed 7 Mar 2011.

- 27.Dinour L, Fuentes L, Freudenberg N. Reversing Obesity in New York City: An Action Plan for Reducing the Promotion and Accessibility of Unhealthy Food, Public Health Association of New York City. New York, NY: City University of New York Campaign Against Diabetes and the Public Health Association of New York City; 2008.

- 28.Frieden TR, Bassett MT, Thorpe LE, Farley TA. Public health in New York City, 2002–2007: confronting epidemics of the modern era. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):966–977. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvard Evaluation Exchange. Advocacy and policy change. Eval Exch. 2007; 13:1;1–16. http://www.hfrp.org/var/hfrp/storage/original/application/6bdf92c3d7e970e7270588109e23b678.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2011.

- 30.Organizational Research Services. A guide to measuring advocacy and policy 2007. http://www.organizationalresearch.com/publications/a_guide_to_measuring_advocacy_and_policy.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2011.

- 31.Sayre WS, Kaufman H. Governing New York City: politics in the metropolis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. [Affordable Care Act]. Title IV, Subtitle C, Section 4205. March 23, 2010.

- 33.Hartocolis A. Failure of state soda tax plan reflects power of an antitax message. New York Times. July 3, 2010: A14.

- 34.Brownell KD, Frieden TR. Ounces of prevention—the public policy case for taxes on sugared beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1805–1808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brustein J. Fast food and zoning. Gotham Gazette. June 26, 2006. http://www.gothamgazette.com/blogs/wonkster/2006/06/26/fast-food-and-zoning/. Accessed 7 Mar 2011.

- 36.Wallack L, Lawrence R. Talking about public health: developing America’s “second language”. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(4):567–570. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2. New York, NY: Longman; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor DE. The rise of the environmental justice paradigm injustice framing and the social construction of environmental discourses. Am Behav Sci. 2000;43(4):508–580. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sondik EJ, Huang DT, Klein RJ, Satcher D. Progress toward the healthy people 2010 goals and objectives. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:271–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Summers C, Cohen L, Havusha A, Sliger F, Farley T. Take Care New York 2012: A Policy for a Healthier New York City. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2009.

- 41.Rowitz L. Public Health Leadership. Putting Principles into practice. 2. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlet; 2009. [Google Scholar]